Abstract

Aims

We aimed to determine whether in children with dilated cardiomyopathy repeated measurement of known risk factors for death or heart transplantation (HTx) during disease progression can identify children at the highest risk for adverse outcome.

Methods and results

Of 137 children we included in a prospective cohort, 36 (26%) reached the study endpoint (SE: all‐cause death or HTx), 15 (11%) died at a median of 0.09 years [inter‐quartile range (IQR) 0.03–0.7] after diagnosis, and 21 (15%) underwent HTx at a median of 2.9 years [IQR 0.8–6.1] after diagnosis. Median follow‐up was 2.1 years [IQR 0.8–4.3]. Twenty‐three children recovered at a median of 0.6 years [IQR 0.5–1.4] after diagnosis, and 78 children had ongoing disease at the end of the study. Children who reached the SE could be distinguished from those who did not, based on the temporal evolution of four risk factors: stunting of length growth (−0.42 vs. −0.02 length Z‐score per year, P < 0.001), less decrease in N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP) (−0.26 vs. −1.06 2log pg/mL/year, P < 0.01), no decrease in left ventricular internal diastolic dimension (LVIDd; 0.24 vs. −0.60 Boston Z‐score per year, P < 0.01), and increase in New York University Pediatric Heart Failure Index (NYU PHFI; 0.49 vs. −1.16 per year, P < 0.001). When we compared children who reached the SE with those with ongoing disease (leaving out the children who recovered), we found similar results, although the effects were smaller. In univariate analysis, NT‐proBNP, length Z‐score, LVIDd Z‐score, global longitudinal strain (%), NYU PHFI, and age >6 years at presentation (all P < 0.001) were predictive of adverse outcome. In multivariate analysis, NT‐proBNP appeared the only independent predictor for adverse outcome, a two‐fold higher NT‐proBNP was associated with a 2.8 times higher risk of the SE (hazard ratio 2.78, 95% confidence interval 1.81–3.94, P < 0.001).

Conclusions

The evolution over time of NT‐proBNP, LVIDd, length growth, and NYU PHFI identified a subgroup of children with dilated cardiomyopathy at high risk for adverse outcome. In this sample, with a limited number of endpoints, NT‐proBNP was the strongest independent predictor for adverse outcome.

Keywords: Dilated cardiomyopathy, Paediatric cardiology, Risk factors

Introduction

In children with dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), up to 50% of children die or undergo heart transplantation (HTx) within 5 years after diagnosis. 1 , 2 , 3 DCM is the most common indication for HTx in children. Worldwide, several large paediatric DCM cohorts have reported risk factors at presentation for adverse outcome and identified older age (>6 years), worse left ventricular (LV) fractional shortening, congestive heart failure at presentation, idiopathic DCM, and higher N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP) as risk factors for death or HTx. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 Previously, we reported on similar risk factors at presentation. 5 Also, we demonstrated that follow‐up parameters like NT‐proBNP, 6 min walking distance, and longitudinal strain, all obtained relatively early after presentation in cross‐sections of our national cohort of children with DCM, contained important prognostic information. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 However, changes in these risk factors during the further course of the disease, alone or in concert, might hold valuable prognostic information as well. 2 , 6 , 9 This may further pinpoint the group of children at the highest risk for adverse outcome, which is essential as these are the patients who should be monitored closely and, importantly, be listed for HTx at a timely stage.

In this present study, we prospectively and repeatedly collected a set of established clinical, laboratory, and echocardiographic risk factors for death and transplantation in a national cohort of children with DCM. We explored the temporal evolution of these factors and their potential for clinical decision making.

Methods

Patients

Data were collected in a multicentre, prospective study design. Patients from eight tertiary cardiac centres were included from October 2010 to July 2017. We enrolled children with prior (until 2010) or new diagnosis (from 2010 onward). As the purpose was to study primary cardiac disease with impaired systolic function, DCM was defined as the presence of impaired systolic function based on echocardiography: a fractional shortening ≤25% in combination with LV end‐diastolic dimension >+2 Z‐score for body surface area. Patients with congenital heart disease, neuromuscular disease, or systemic diseases that transiently impaired systolic function were excluded. Data were collected during routine outpatient clinic visits or coincided with hospital admissions. In the first year after diagnosis, patients were evaluated 1–4 times per year, and 1–2 times per year thereafter, depending on the frequency of outpatient visits. Subjects were followed until death or HTx, until the age of 18 years, or until the last outpatient visit within the study window. This study was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the Erasmus MC (MEC 2014‐062) and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All parents as well as children ≥12 years gave written informed consent.

Study variables

In this study, we focused on six known risk factors for adverse outcome.

N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide

N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide values were measured using the Elecsys® assay in all participating centres.

New York University Pediatric Heart Failure Index

New York University Pediatric Heart Failure Index (NYU PHFI) is a paediatric heart failure score that quantifies the degree of heart failure in terms of symptoms and medication use and ranges from 0 to 30 points. 10 The treating paediatric cardiologist completed the NYU PHFI.

Length Z‐score

Length was normalized to Z‐scores using Growth Analyser©, which is based on reference values for Dutch children. 11

Left ventricular internal diastolic diameter

A standardized echocardiogram was performed, and data were analysed using the mean value of three consecutive cardiac cycles. Echocardiograms were analysed by study personnel who were blinded to the patient's name, previous echocardiograms, and other study results. The left ventricular internal diastolic diameter (LVIDd) was normalized to a Boston Z‐score for body surface area, age, and gender. 12

Global longitudinal strain

Global longitudinal strain (GLS) was calculated as the mean of the peak strain of all LV segments in a longitudinal six‐segment model as previously described. 8

Six minute walking distance

The distance walked within 6 min on a 8 m track was recorded and expressed as percentage of predicted (6MWD%) according to Geiger et al., accounting for height, gender, and age. 7 , 13

The clinical team was blinded to the results of the 6MWD% and GLS, and the other study variables were readily available. In addition to the previously mentioned study variables, DCM aetiology, age at diagnosis, weight (normalized to Z‐score), and current heart failure medications were collected as well. Genetic aetiology was defined as the presence of a mutation in a known pathogenic DCM gene. Myocarditis was accepted as aetiology if diagnosis was definite or probable. 14

Study endpoint

The study endpoint (SE) was all‐cause death or HTx. We also recorded the status of the surviving patients at the end of the study period: ongoing disease or recovered. Recovery was defined as two consecutive echocardiograms obtained with at least 1 month interval, with normalized LVIDd and fractional shortening, and the date of the first normalized echocardiogram was considered as date of recovery.

Statistical analysis

Continuous baseline variables with normal distribution are described as mean (standard deviation) or as median [inter‐quartile range (IQR)] otherwise. Categorical baseline variables are described as numbers and percentages. Differences in characteristics between patients with and without the SE were compared by Student's t‐tests (normal distribution) or Mann–Whitney U tests. We applied the method of Kaplan–Meier to study survival and transplant‐free survival.

To explore the temporal evolution of the study variables, while accounting for the correlation between measurements in the individual patient, we applied a linear mixed‐effects model (LMEM) for longitudinal data. To study the association between study variables (repeatedly measured) and the SE, we subsequently combined the LMEM with a Cox proportional hazard regression model in a so‐called joint model (JM). In the multivariable joint model, we included stepwise the studied risk factors starting with NT‐proBNP based on the fact that NT‐proBNP has shown to be a robust marker for outcome. Results of LMEM analyses are reported as mean values [95% confidence intervals (CIs)], whereas results of the JM analyses are reported as hazard ratio and 95% CI.

To further characterize the children who reached the SE, we compared them with the patients who remained endpoint free but still had ongoing disease at the end of the follow‐up period, thus leaving out the children who recovered. Temporal evolution of the study variables was studied, in the same way as described previously. The level of statistical significance for all analyses was set at P = 0.05. Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 24 (IBM, New York, NY, USA) and R statistical software Version 3.5.1 (free software, package JMbayes, see https://www.r-project.org/foundation/).

Results

Patients and clinical outcome

A total of 137 children with DCM were included; three patients left the study early and were censored at their last study visit. Of these 137 children, 96 were included directly after diagnosis, whereas 41 children had a prior diagnosis. Thirty‐six children (26%) reached the SE, 15 children (11%) died, and 21 children (15%) underwent transplantation. Seventeen children reached an SE within 1 year after diagnosis (12 died and 5 underwent transplantation), and nine of those 17 early endpoints were reached within 1 month after diagnosis (seven children died and two underwent transplantation). The majority of deaths (12 out of 15; 80%) occurred within 1 year after diagnosis. Median time from diagnosis to death was 1 month (0.09 years [IQR 0.03–0.7]), and median time to HTx was 2.9 years [IQR 0.8–6.1]. At some stage, during the first year after inclusion, the majority of children were on heart failure medication: 84% of children were on an ACE inhibitor, 65% were on a beta‐blocker, and 87% were on one of both. Sixteen of 17 children who were not on oral heart failure medication reached an SE before medication could be started. All medications were up‐titrated to the maximum tolerated dose at the discretion of the treating physician.

At the end of the study, after a median follow‐up of 3.0 years [IQR 1.5–4.7], 23 children (24% of newly diagnosed patients) had recovered and 78 children (57%) had ongoing disease. Time from diagnosis to recovery was 0.6 years [IQR 0.5–1.4]. When comparing children who reached an SE and those who did not, we found no important differences in patient and clinical characteristics (see Table 1 ).

TABLE 1.

Patient and clinical characteristics at the time of diagnosis, comparing children who died or underwent transplantation with children who survived without transplantation

| Study endpoint N = 36 | No study endpoint N = 101 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) [IQR] a | 5.3 [0.2–11.3] | 0.9 [0.1–4.8] |

| <1 year, n (%) | 14 (39) | 50 (49) |

| 1 to <6 years, n (%) | 5 (14) | 28 (28) |

| 6 to <18 years, n (%) | 17 (47) | 23 (23) |

| Female, n (%) b | 23 (64) | 45 (45) |

| Time Dx to study inclusion (years) [IQR] a | 0.01[0.0–2.5] | 0.05 [0.0–2.3] |

| Time inclusion to last FU (years) [IQR] a | 0.15 [0–1.7]* | 3.0 [1.5–4.7] |

| Time diagnosis to last FU [IQR] a | 1.3 [0.1–4.3]* | 3.5 [2.0–6.1] |

| Primary diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| Idiopathic | 16 (44) | 51 (50) |

| Myocarditis | 3 (8) | 20 (20) |

| Familial | 6 (17) | 12 (12) |

| Inborn error of metabolism | 2 (6) | 2 (2) |

| Malformation syndrome | 0 | 2 (2) |

| Anthracyclin related | 1 (3) | 7 (7) |

| Other | 8 (22) | 7 (7) |

| Weight for age, Z‐score, mean (SD) c | −0.6 (1.7) | −0.8 (1.3) |

| Weight for height, Z‐score, mean (SD) | −0.4 (1.5) | −0.4 (1.8) |

| Height for age, Z‐score, mean (SD) | −0.4 (1.4) | −0.5 (1.5) |

| Shortening fraction (%) [IQR] | 13 [9–16] | 16 [12–20] |

| NT‐proBNP (pg/mL) [IQR] | 9922 [2592–25 974] | 4180 [520–25 057] |

Dx, diagnosis; FU, follow‐up; IQR, inter‐quartile range; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide; SD, standard deviation.

Continuous variables as mean (SD) or median [IQR].

Mann–Whitney U test.

χ 2 test.

Weight for age only in children under 15 months (n = 43).

P < 0.05.

In children who were included directly after diagnosis (n = 96), 1 year survival was 88% (95% CI 83–95%) and 5 year survival was 82% (95% CI 74–90%). The transplant‐free survival was 82% (95% CI 74–89%) after 1 year and 72% (95% CI 62–82%) after 5 years (Supporting Information, Figure S1 ).

In the children with a previous diagnosis (n = 41), 13 patients (32%) reached an SE, 2 children died, and 11 patients underwent transplantation. Median time from diagnosis to inclusion was 3.8 years [IQR 2.5–8.7], and median time from diagnosis to SE was 6.0 years [IQR 3.1–9.7]. At the end of the study, 28 patients had ongoing disease and no patient had recovered.

Differences in risk factors, study endpoint vs. no study endpoint

At the moment of first diagnosis, children who ultimately reached the SE had an unfavourable clinical profile compared with those who remained event‐free. In particular, (mean) NT‐proBNP levels and NYU PHFI scores were higher, whereas GLS and 6MWD% were lower (Table 2 ).

TABLE 2.

Differences in risk factors between patients who reached the study endpoint of all‐cause death or heart transplantation and those who remained endpoint free

| Measurement | Patients | Measures | Mean value (95% CI) at diagnosis | Mean (95% CI) change per year | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | N | No SE | SE | P‐value a | No SE | SE | P‐value a | |

| NT‐proBNP (2log pg/mL) | 114 | 637 | 10.9 (10.5, 11.3) | 13.2 (12.5, 13.9) | <0.001 | −1.06 (−1.27, −0.85) b | −0.26 (−0.68, 0.16) | 0.001 |

| Length Z‐score | 137 | 974 | −0.67 (−0.89, −0.44) | −0.18 (−0.58, 0.22) | 0.040 | −0.02 (−0.08, 0.04) | −0.42 (−0.56, −0.27) b | <0.001 |

| LVIDd Boston Z‐score | 136 | 587 | 4.5 (3.9, 5.2) | 5.4 (4.2, 6.7) | 0.221 | −0.60 (−0.82, −0.38) b | 0.24 (−0.28, 0.75) | 0.004 |

| Global peak strain (%) | 112 | 416 | 13.3 (12.4, 14.2) | 9.8 (7.7, 11.9) | 0.003 | 1.14 (0.75, 1.52) b | 0.55 (−0.51, 1.62) | 0.313 |

| 6MWD% (%) | 57 | 277 | 73.0 (67.0, 79.0) | 50.7 (39.6, 61.7) | 0.001 | −0.23 (−0.92, 0.45) | 0.22 (−1.47, 1.90) | 0.627 |

| NYU PHFI | 133 | 844 | 7.8 (7.1, 8.6) | 10.6 (9.2, 11.9) | <0.001 | −1.16 (−1.41, −0.91) b | 0.49 (−0.13, 1.10) | <0.001 |

CI, confidence interval; LVIDd, left ventricular internal diastolic dimension; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide; NYU PHFI, New York University Pediatric Heart Failure Index; SE, study endpoint.

Results are derived from linear mixed‐effects model with risk factor as dependent variable and time, classification (SE vs. still diseased), and time × classification as independent variables.

P‐value for the difference between patients who reached the composite SE of all‐cause death or heart transplantation and those who survived (without transplantation).

The slope is significantly (P‐value <0.05) different from 0.

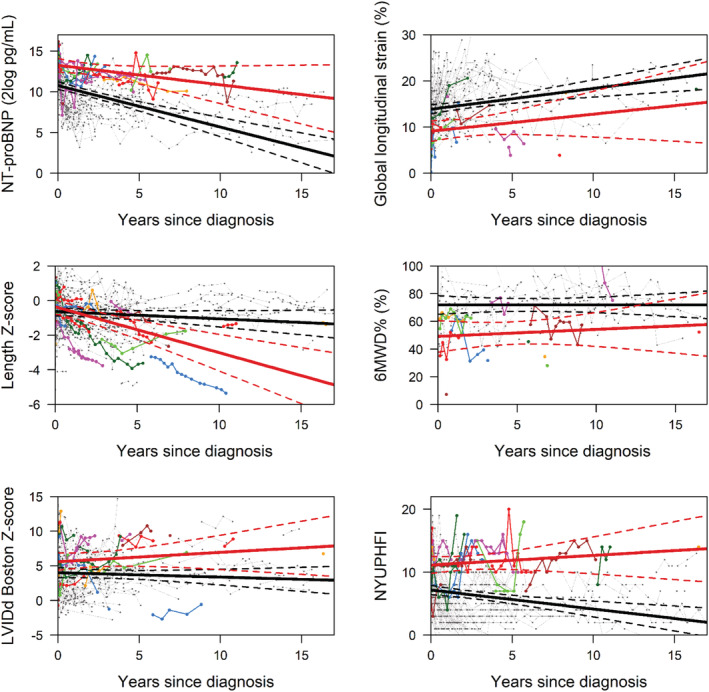

The temporal evolution of four risk factors was clearly different between children with and without the SE (Table 2 and Figure 1 ). NT‐proBNP levels, LVIDd, and NYU PHFI score remained high in those who reached the SE, while event‐free children showed (steadily) decreasing values. Furthermore, length growth was severely stunted in children with the SE, while a normal length growth was maintained over time in their event‐free counterparts.

FIGURE 1.

Serial measurement of risk factors: N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP) (2log pg/mL), length Z‐score, left ventricular internal diastolic dimension (LVIDd) Boston Z‐score, global longitudinal strain (%), 6MWD% (%), and New York University Pediatric Heart Failure Index (NYU PHFI). The average estimates of the longitudinal trajectory risk factors: the black line indicates the patients without a study endpoint and the red line the patients with a study endpoint. The dashed lines depict the 95% confidence interval. The coloured lines show the individual patients with a study endpoint.

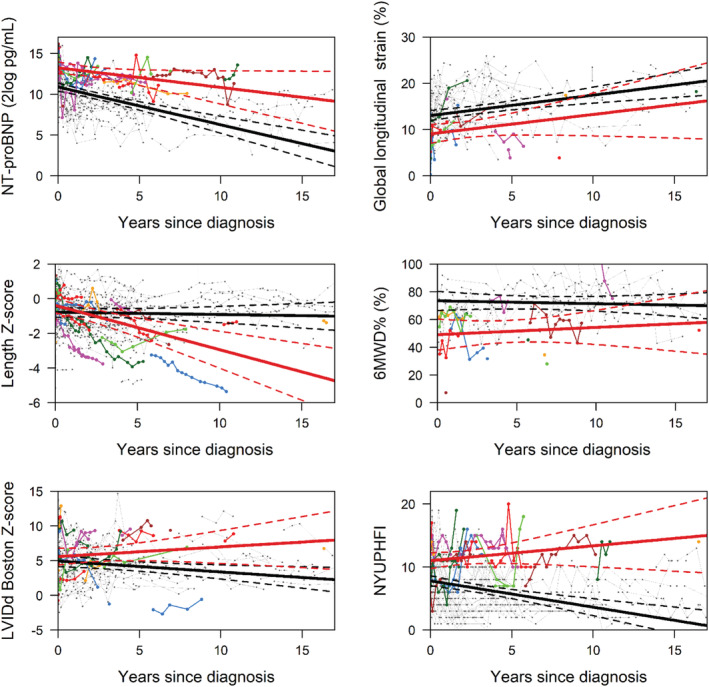

Differences in risk factors, study endpoint vs. ongoing disease

Comparable differences between patients with and without SE were observed in a sensitivity analysis that excluded the patients who recovered, although effect sizes were smaller (Table 3 and Figure 2 ). Thus, in children with the SE, the mean value at the time of diagnosis of NT‐proBNP and NYU PHFI were significantly higher, and GLS and 6MWD% were significantly lower. Furthermore, in children with the SE, NT‐proBNP, LVIDd, and NYU PHFI all remained high, while in the children without the SE, all decreased over time. Length Z‐score indicated that in children who reached an endpoint, length growth was severely stunted, while in those with ongoing disease, growth was less severely impaired.

TABLE 3.

Differences in risk factors between patients who reached the study endpoint of all‐cause death or heart transplantation and those who survived (without transplantation) but remained diseased

| Measurement | Patients | Measures | Mean value (95% CI) at diagnosis | Mean (95% CI) change per year | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | N | Still diseased | SE | P‐value a | Still diseased | SE | P‐value a | |

| NT‐proBNP (2log pg/mL) | 93 | 521 | 10.8 (10.3, 11.4) | 13.2 (12.5, 14.0) | <0.001 | −0.41 (−0.49, −0.33) b | −0.19 (−0.38, −0.01) b | 0.037 |

| Length Z‐score | 114 | 638 | −0.67 (−0.95, −0.39) | −0.20 (−0.63, 0.23) | 0.076 | −0.04 (−0.06, −0.01) b | −0.29 (−0.37, −0.22) b | <0.001 |

| LVIDd Boston Z‐score | 113 | 467 | 5.2 (4.5, 6.0) | 5.6 (4.4, 6.8) | 0.618 | −0.23 (−0.33, −0.12) b | 0.14 (−0.11, 0.39) | 0.010 |

| Global peak strain (%) | 89 | 299 | 13.0 (11.9, 14.1) | 9.0 (7.0, 11.1) | 0.001 | 0.42 (0.24, 0.60) b | 0.43 (−0.04, 0.91) | 0.948 |

| 6MWD% (%) | 53 | 262 | 74.1 (67.6, 80.6) | 50.7 (39.6, 61.8) | 0.001 | −0.34 (−1.05, 0.37) | 0.20 (−1.49, 1.90) | 0.560 |

| NYU PHFI | 110 | 672 | 8.45 (7.5, 9.2) | 10.6 (9.2, 11.9) | 0.006 | −0.49 (−0.60, −0.38) b | 0.36 (0.07, 0.66) b | <0.001 |

CI, confidence interval; LVIDd, left ventricular internal diastolic dimension; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide; NYU PHFI, New York University Pediatric Heart Failure Index; SE, study endpoint.

Results are derived from linear mixed‐effects model with risk factor as dependent variable and time, classification (SE vs. still diseased), and time × classification as independent variables.

P‐value for the difference between patients who reached the composite SE of all‐cause death or heart transplantation (‘SE’) and those who survived (without transplantation) but remained diseased (‘still diseased’).

The slope is significantly (P‐value <0.05) different from 0.

FIGURE 2.

Serial measurement of risk factors: N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP) (2log pg/mL), length Z‐score, left ventricular internal diastolic dimension (LVIDd) Boston Z‐score, global longitudinal strain (%), 6MWD% (%), and New York University Pediatric Heart Failure Index (NYU PHFI). The average estimates of the longitudinal trajectory risk factors: the black line indicates the patients with ongoing disease and the red line the patients with a study endpoint. The dashed lines depict the 95% confidence interval. The coloured lines show the individual patients with a study endpoint.

Risk factors for death or heart transplantation

Factors that were associated with an increased risk of death or HTx included age older than 6 years at diagnosis and at any time during follow‐up: NT‐proBNP, LVIDd Z‐score, GLS, 6MWD%, and NYU PHFI (Table 4 ). In multivariable analyses, NT‐proBNP remained the only independent risk factor for reaching an SE.

TABLE 4.

Risk factors for the composite study endpoint of death or heart transplantation

| No. of patients | No. of repeated observations | No. of endpoints | HR (95% CI) | P‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age over 6 years | 137 | — | 36 | 3.97 (1.94, 8.15) | <0.001 |

| Idiopathic DCM | 137 | — | 36 | 0.79 (0.41, 1.55) | 0.502 |

| NT‐proBNP (2log pg/mL) | 114 | 637 | 32 | 2.97 (2.10, 3.81) | <0.001 |

| Length Z‐score | 137 | 974 | 36 | 0.78 (0.58, 1.08) | 0.136 |

| LVIDd Boston Z‐score | 136 | 587 | 35 | 1.27 (1.10, 1.48) | <0.001 |

| Global peak strain (%) | 112 | 416 | 22 | 0.35 (0.16, 0.62) | <0.001 |

| 6MWD% (%) | 57 | 277 | 14 | 0.90 (0.87, 0.94) | <0.001 |

| NYU PHFI a | 133 | 844 | 33 | 3.31 (2.41, 4.74) | <0.001 |

| Age over 6 years | 114 | 637 | 32 | 3.16 (0.82, 13.4) | 0.078 |

| NT‐proBNP (2log pg/mL) | 2.95 (2.16, 3.87) | <0.001 | |||

| Idiopathic DCM | 114 | 637 | 32 | 1.85 (0.43, 12.1) | 0.374 |

| NT‐proBNP (2log pg/mL) | 2.98 (1.55, 3.91) | <0.001 | |||

| Length Z‐score | 114 | 638 | 32 | 1.09 (0.63, 1.90) | 0.751 |

| NT‐proBNP (2log pg/mL) | 7.31 (3.99, 13.4) | <0.001 | |||

| LVIDd Boston Z‐score | 114 | 638 | 32 | 0.91 (0.74, 1.11) | 0.334 |

| NT‐proBNP (2log pg/mL) | 8.35 (4.26, 16.4) | <0.001 | |||

| Global peak strain (%) | 97 | 579 | 19 | 0.89 (0.74, 1.08) | 0.233 |

| NT‐proBNP (2log pg/mL) | 8.50 (3.27, 22.1) | <0.001 | |||

| 6MWD% (%) | 46 | 308 | 13 | 0.95 (0.89, 1.01) | 0.088 |

| NT‐proBNP (2log pg/mL) | 5.24 (1.57, 17.5) | 0.007 | |||

| NYU PHFI a | 107 | 536 | 29 | 0.83 (0.24, 2.84) | 0.766 |

| NT‐proBNP (2log pg/mL) | 11.0 (3.30, 36.4) | <0.001 |

CI, confidence interval; DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy; HR, hazard ratio; LVIDd, left ventricular internal diastolic dimension; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide; NYU PHFI, New York University Pediatric Heart Failure Index.

After Box–Cox transformation (λ = 0.75).

Discussion

In this study, we found that the temporal evolution of four risk factors distinguished the children who died or underwent transplantation from those who had ongoing disease or who recovered: no decrease in NT‐proBNP or LVIDd, a severe decrease in length Z‐score, and an increase in NYU PHFI. Similarly, when comparing children who reached an endpoint with children with ongoing disease solely, excluding those who recovered, we found comparable differences in the evolution of risk factors, although the effect size was smaller. In the multivariate analysis, NT‐proBNP remained the only independent risk factor for adverse outcome.

We performed two analyses and excluded the children who recover in the secondary analysis because, in general, children who recover tend do clinically well at a relatively early stage after diagnosis. The clinical challenge is to identify those children who are at the highest risk for adverse outcome and should be considered for HTx. In this study, 23% of the children, who newly presented, recovered and median time from diagnosis to recovery was 0.6 years and confirmed that recovery tends to be an early event. 1 , 3 This is the first study to our knowledge to analyse this subgroup of children who remain ill but do not reach the SE. The finding that the previously mentioned risk factors also discern these children from those who reached an SE supports outpatient management and the decision to suspend listing for HTx.

In the adult counterpart of paediatric DCM, non‐ischaemic cardiomyopathy, studies of risk factors for outcome have focused on the prevention of sudden cardiac death. 15 However, in children with DCM, the risk of sudden cardiac death is considerably lower than in adults, and most children die or undergo HTx because of pump failure. 16 Studies on risk factors for adverse outcome in adult non‐ischaemic heart failure secondary to pump failure are, therefore, potentially better comparable with the results of the paediatric studies. In parallel with the risk factors we noted in paediatric DCM, natriuretic peptides, including NT‐proBNP, have been shown robust prognostic markers for outcome in adult heart failure, including also in the non‐ischaemic subgroup. 17 , 18 , 19 Longitudinal strain on CMR imaging has been shown to have incremental predictive value for adverse events in addition to late gadolinium enhancement and indexed LV end‐diastolic volume. 20 In contrast, LV dimension has not been identified as a solid marker for adverse events. 21 However, in patients demonstrating reverse remodelling, LV dimensions at presentation were lower and significantly decreased over time. 22 The 6 min walking test at presentation and the change during follow‐up have been associated with heart failure outcome. 23 However, the application of the test in adults has been limited but may be useful in those with severe heart failure. 24

When comparing the results of the previously mentioned adult reports with the results of our study, NT‐proBNP also remains a strong predictor of outcome in paediatric DCM. Even after exclusion of the children who recovered, the differences in temporal evolution of NT‐proBNP remained significant. In this study, we reported a difference in NT‐proBNP at diagnosis between children who reached the SE and those who did not. This seems to contradict our previous publication in which we reported no difference in NT‐proBNP at diagnosis. 6 A likely explanation is the steep decline of NT‐proBNP in children without the SE in the first 30 days after diagnosis, as shown by den Boer et al. 6 In this study, we analysed the data in one time frame, and the linear model underestimated NT‐proBNP at diagnosis. We could confirm this as median NT‐proBNP at diagnosis was not different in standard statistical tests (Table 1 ). Our results further corroborate the association of NT‐proBNP and outcome in children and adults with heart failure. 6 , 17 , 25 , 26 , 27 Whether the evolution of NT‐proBNP truly is the only predictor of outcome or whether the other risk factors also hold independent predictive information remains to be studied in a larger cohort or with longer follow‐up. Moreover, our findings apply to the midterm outcome with a median time after diagnosis to last follow‐up of 3.5 years.

Although in the multivariate analysis all risk factors but NT‐pro BNP lost their association with the SE, the temporal evolution of the other three risk factors still holds important information. First, LVIDd in children who reached an endpoint did not change over time in contrast to children not reaching an endpoint where LVIDd decreased, even after exclusion of children who recovered (Tables 2 and 3 ). Temporal evolution of GLS cannot be used to predict outcome because the slopes are not different in the two analyses. However, GLS at the time of diagnosis still might be useful. In the model, the intercepts of GLS were significantly different between the two groups (Tables 2 and 3 ), suggesting that early after presentation, it may be an indicator for outcome. That observation is compatible with our previous report that lower GLS was associated with an increased risk of death or HTx in a cross‐sectional sample and similar to observations in adults with chronic heart failure. 8 , 28 The second and third risk factors specifically pertain to the paediatric population: length Z‐score and a paediatric heart failure score (NYU PHFI). Length growth is considered a solid proxy for overall health in children and provides a long‐term reflection of disease severity. The development of length Z‐score distinguished children who reached an endpoint from those with ongoing disease (Table 3 ). In clinical practice, length growth virtually ceased in children reaching an endpoint. Similarly, Alvarez et al. reported that small height for age was associated with a risk of death, but not for being listed for transplantation, also suggesting that length growth may be a useful indicator for disease severity in these children. 3 Previously, we reported that NYU PHFI independently predicted death and HTx in children with DCM in a cross‐sectional sample. 29 Now we have demonstrated that children who reach the SE were characterized by an increase in NYU PHFI opposed to those with ongoing disease.

In the light of the interpretation and generalization of our findings, it is important that after the first year after diagnosis, the (transplant‐free) survival curves of the Pediatric Cardiomyopathy Registry and the National Australian Childhood Cardiomyopathy Study are similar to ours. 1 , 2 We have previously reported a low HTx rate in children with DCM in the first year after diagnosis, without an increase in mortality. 5 The data presented in this study confirm that finding and support the idea that a low early HTx rate does not lead to an increase in mortality or Htx rate in the years following diagnosis as a result of postponing HTx. This implies that the children with DCM in both cohorts are comparable in disease severity. The results we found would therefore be applicable in other populations of children with DCM, after the first year after diagnosis.

Although we are unable to calculate a risk score that help us to select children for listing for transplantation, from our data, three groups with distinguishable profiles emerge: one group with a high likelihood of recovery, one group with a low likelihood of (early) recovery, but a low risk of adverse outcome, and, finally, one group with a high risk of adverse events. In our programme, children are listed for transplantation early after presentation if they cannot be weaned off inotropes after multiple attempts or are sliding on inotropes and/or require ventricular assist device support. 5 If discharged, oral heart failure therapy is optimized and the decision to list for transplantation is individualized, but often postponed until (renewed) admission for inotropic and/or ventricular assist device support is necessary. Children with a high‐risk profile are monitored closely. In all others, 3 month interval follow‐up is planned and persistent and/or progressive increments in NT‐proBNP are considered warning signs of deterioration and are used to monitor these children as high risk.

Study limitations

This study has limitations. First, our study cohort is a combination of two cohorts and consists of children with a prior diagnosis before inclusion in this study, as well as children who are included directly after diagnosis. This may have induced a selection bias. However, the outcome of the cohort of newly diagnosed children that we included (Supporting Information, Figure S1 ) is the same as the outcome of the children that we previously reported that presented between 2005 and 2010, indicating that the large majority of children that we included with a prior diagnosis were obtained from a cohort with the same characteristics. 5 Second, the primary aim of our study was to evaluate the prognostic value of the temporal evolution of (previously identified) risk factors in children with DCM. Therefore, we did not include a control group of children without DCM, and hence, our study was not suited to evaluate hypotheses with respect to such subjects. Noteworthy, in this respect, the design of our study is similar to numerous other studies on variables carrying prognostic information in paediatric and adult heart failure. 1 , 30 , 31 Third, missing data were an issue, as may be expected in a longitudinal multicentre study in children. NT‐proBNP measurements were available in all centres except one, where BNP measurements were reported. Furthermore, strain analyses could not be obtained from the data sets available on all echo machines throughout the course of the study. The 6MWD% could only be obtained in outpatient children older than 6 years, but not in those hospitalized at the ICU. Fourth, the number of endpoints was limited, which may have hampered the power of our analyses. However, we still found robust significances for most of the regression and univariate analyses with the data that were available. Furthermore, the multivariate analysis was likely affected by the limited number of endpoints. Inspection of the results of the multivariate analysis suggests that the missing data for NT‐proBNP and the strain analyses were not the critical factor. Lastly, the decision to list a patient for HTx is based on multiple clinical factors. It could be that the reported risk factors predict decision making by clinicians rather than outcome. However, the children that underwent HTx were in such a condition that they most likely would have died otherwise. 32

Conclusions

In summary, we conclude that in children with DCM, change over time in known risk factors for death or HTx is predictive for outcome. In children who do not recover, persistent high levels of NT‐proBNP, no decrease in LVIDd, severe stunting of growth, and an increase in the heart failure score identify those at the highest risk for death or HTx. In this study, with a limited number of SEs, we identified NT‐proBNP as the strongest independent predictor for adverse outcome.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Funding

M.v.d.M. was supported by a joint grant from ‘Stichting Hartedroom’ (Rotterdam, The Netherlands) and the ‘Netherlands Heart Foundation’ (Hartstichting, 2013T087).

Supporting information

Figure S1. Kaplan–Meier plot showing survival and transplant‐free survival since diagnosis of 96 newly diagnosed children with DCM

van der Meulen, M. , den Boer, S. , du Marchie Sarvaas, G. J. , Blom, N. , ten Harkel, A. D. J. , Breur, H. M. P. J. , Rammeloo, L. A. J. , Tanke, R. , Bogers, A. J. J. C. , Helbing, W. A. , Boersma, E. , and Dalinghaus, M. (2021) Predicting outcome in children with dilated cardiomyopathy: the use of repeated measurements of risk factors for outcome. ESC Heart Failure, 8: 1472–1481. 10.1002/ehf2.13233.

References

- 1. Towbin JA, Lowe AM, Colan SD, Sleeper LA, Orav EJ, Clunie S, Messere J, Cox GF, Lurie PR, Hsu D, Canter C, Wilkinson JD, Lipshultz SE. Incidence, causes, and outcomes of dilated cardiomyopathy in children. JAMA 2006; 296: 1867–1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alexander PM, Daubeney PE, Nugent AW, Lee KJ, Turner C, Colan SD, Robertson T, Davis AM, Ramsay J, Justo R, Sholler GF, King I, Weintraub RG, National Australian Childhood Cardiomyopathy Study . Long‐term outcomes of dilated cardiomyopathy diagnosed during childhood: results from a national population‐based study of childhood cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2013; 128: 2039–2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alvarez JA, Orav EJ, Wilkinson JD, Fleming LE, Lee DJ, Sleeper LA, Rusconi PG, Colan SD, Hsu DT, Canter CE, Webber SA, Cox GF, Jefferies JL, Towbin JA, Lipshultz SE, Pediatric Cardiomyopathy Registry Investigators . Competing risks for death and cardiac transplantation in children with dilated cardiomyopathy/clinical perspective. Circulation 2011; 124: 814–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Daubeney PE, Nugent AW, Chondros P, Carlin JB, Colan SD, Cheung M, Davis AM, Chow CW, Weintraub RG, National Australian Childhood Cardiomyopathy Study . Clinical features and outcomes of childhood dilated cardiomyopathy: results from a national population‐based study. Circulation 2006; 114: 2671–2678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. den Boer SL, van Osch‐Gevers ML, van Ingen G, du Marchie Sarvaas GJ, van Iperen GG, Tanke RB, Backx AP, Ten Harkel AD, Helbing WA, Delhaas T, Bogers AJ. Management of children with dilated cardiomyopathy in The Netherlands: implications of a low early transplantation rate. J Heart Lung Transplant 2015; 34: 963–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. den Boer SL, Rizopoulos D, du Marchie Sarvaas GJ, Backx AP, Ten Harkel AD, van Iperen GG, Rammeloo LA, Tanke RB, Boersma E, Helbing WA, Dalinghaus M. Usefulness of serial N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide measurements to predict cardiac death in acute and chronic dilated cardiomyopathy in children. Am J Cardiol 2016; 118: 1723–1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. den Boer SL, Flipse DH, van der Meulen MH, Backx AP, du Marchie Sarvaas GJ, Ten Harkel AD, van Iperen GG, Rammeloo LA, Tanke RB, Helbing WA, Takken T, Dalinghaus M. Six‐minute walk test as a predictor for outcome in children with dilated cardiomyopathy and chronic stable heart failure. Pediatr Cardiol 2017; 38: 465–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. den Boer SL, Sarvaas GJD, Klitsie LM, van Iperen GG, Tanke RB, Helbing WA, Backx APCM, Rammeloo LAJ, Dalinghaus M, ten Harkel ADJ. Longitudinal strain as risk factor for outcome in pediatric dilated cardiomyopathy. Jacc‐Cardiovasc Imaging 2016; 9: 1121–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Medar SS, Hsu DT, Ushay HM, Lamour JM, Cohen HW, Killinger JS. Serial measurement of amino‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide predicts adverse cardiovascular outcome in children with primary myocardial dysfunction and acute decompensated heart failure. Pediatr Crit Care Me 2015; 16: 529–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Connolly D, Rutkowski M, Auslender M, Artman M. The New York University Pediatric Heart Failure Index: a new method of quantifying chronic heart failure severity in children. J Pediatr 2001; 138: 644–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schonbeck Y, Talma H, van Dommelen P, Bakker B, Buitendijk SE, HiraSing RA, van Buuren S. The world's tallest nation has stopped growing taller: the height of Dutch children from 1955 to 2009. Pediatr Res 2013; 73: 371–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sluysmans T, Colan SD. Theoretical and empirical derivation of cardiovascular allometric relationships in children. J Appl Physiol (1985 2005; 99: 445–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Geiger R, Strasak A, Treml B, Gasser K, Kleinsasser A, Fischer V, Geiger H, Loeckinger A, Stein JL. Six‐minute walk test in children and adolescents. J Pediatr 2007; 150: 395–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. den Boer SL, Meijer RP, van Iperen GG, Ten Harkel AD, du Marchie Sarvaas GJ, Straver B, Rammeloo LA, Tanke RB, van Kampen JJ, Dalinghaus M. Evaluation of the diagnostic work‐up in children with myocarditis and idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Pediatr Cardiol 2015; 36: 409–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Halliday BP, Cleland JGF, Goldberger JJ, Prasad SK. Personalizing risk stratification for sudden death in dilated cardiomyopathy: the past, present, and future. Circulation 2017; 136: 215–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pahl E, Sleeper LA, Canter CE, Hsu DT, Lu M, Webber SA, Colan SD, Kantor PF, Everitt MD, Towbin JA, Jefferies JL, Kaufman BD, Wilkinson JD, Lipshultz SE, Pediatric Cardiomyopathy Registry Investigators . Incidence of and risk factors for sudden cardiac death in children with dilated cardiomyopathy: a report from the Pediatric Cardiomyopathy Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012; 59: 607–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gardner RS, Chong KS, Morton JJ, McDonagh TA. A change in N‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide is predictive of outcome in patients with advanced heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2007; 9: 266–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Luers C, Schmidt A, Wachter R, Fritzsche F, Sutcliffe A, Kleta S, Zapf A, Hagenah G, Binder L, Maisch B, Pieske B. Serial NT‐proBNP measurements for risk stratification of patients with decompensated heart failure. Herz 2010; 35: 488–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vorovich E, French B, Ky B, Goldberg L, Fang JC, Sweitzer NK, Cappola TP. Biomarker predictors of cardiac hospitalization in chronic heart failure: a recurrent event analysis. J Card Fail 2014; 20: 569–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Riffel JH, Keller MG, Rost F, Arenja N, Andre F, aus dem Siepen F, Fritz T, Ehlermann P, Taeger T, Frankenstein L, Meder B, Katus HA, Buss SJ. Left ventricular long axis strain: a new prognosticator in non‐ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy? J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2016; 18: 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gupta A, Sharma P, Bahl A. Left ventricular size as a predictor of outcome in patients of non‐ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy with severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Int J Cardiol 2016; 221: 310–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Choi JO, Kim EY, Lee GY, Lee SC, Park SW, Kim DK, Oh JK, Jeon ES. Predictors of left ventricular reverse remodeling and subsequent outcome in nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Circ J 2013; 77: 462–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Passantino A, Lagioia R, Mastropasqua F, Scrutinio D. Short‐term change in distance walked in 6 min is an indicator of outcome in patients with chronic heart failure in clinical practice. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006; 48: 99–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Olsson LG, Swedberg K, Clark AL, Witte KK, Cleland JG. Six minute corridor walk test as an outcome measure for the assessment of treatment in randomized, blinded intervention trials of chronic heart failure: a systematic review. Eur Heart J 2005; 26: 778–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Masson S, Latini R, Anand IS, Barlera S, Angelici L, Vago T, Tognoni G, Cohn JN, Val‐He FTI. Prognostic value of changes in N‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide in Val‐HeFT (Valsartan Heart Failure Trial). J Am Coll Cardiol 2008; 52: 997–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sugimoto M, Manabe H, Nakau K, Furuya A, Okushima K, Fujiyasu H, Kakuya F, Goh K, Fujieda K, Kajino H. The role of N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide in the diagnosis of congestive heart failure in children—correlation with the heart failure score and comparison with B‐type natriuretic peptide. Circ J 2010; 74: 998–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kim G, Lee OJ, Kang IS, Song J, Huh J. Clinical implications of serial serum N‐terminal prohormone brain natriuretic peptide levels in the prediction of outcome in children with dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 2013; 112: 1455–1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Motoki H, Borowski AG, Shrestha K, Troughton RW, Tang WH, Thomas JD, Klein AL. Incremental prognostic value of assessing left ventricular myocardial mechanics in patients with chronic systolic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012; 60: 2074–2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. den Boer SL, Baart SJ, van der Meulen MH, van Iperen GG, Backx AP, ten Harkel AD, Rammeloo LA, Sarvaas GJD, Tanke RB, Helbing WA, Utens EM, Dalinghaus M. Parent reports of health‐related quality of life and heart failure severity score independently predict outcome in children with dilated cardiomyopathy. Cardiol Young 2017; 27: 1194–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rorth R, Jhund PS, Kristensen SL, Desai AS, Kober L, Rouleau JL, Solomon SD, Swedberg K, Zile MR, Packer M, McMurray JJV. The prognostic value of troponin T and N‐terminal pro B‐type natriuretic peptide, alone and in combination, in heart failure patients with and without diabetes. Eur J Heart Fail 2019; 21: 40–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tromp J, Richards AM, Tay WT, Teng TK, Yeo PSD, Sim D, Jaufeerally F, Leong G, Ong HY, Ling LH, van Veldhuisen DJ, Jaarsma T, Voors AA, van der Meer P, de Boer RA, Lam CSP. N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide and prognosis in Caucasian vs. Asian patients with heart failure. ESC Heart Fail 2018; 5: 279–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. van der Meulen MH, Dalinghaus M, Maat AP, van de Woestijne PC, van Osch M, de Hoog M, Kraemer US, Bogers AJ. Mechanical circulatory support in the Dutch National Paediatric Heart Transplantation Programme. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2015; 48: 910–916 discussion 916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Kaplan–Meier plot showing survival and transplant‐free survival since diagnosis of 96 newly diagnosed children with DCM