Abstract

Cardiac innervation density generally reflects the levels of nerve growth factor (NGF) produced by the heart—changes in NGF expression within the heart and vasculature contribute to neuronal remodelling (e.g. sympathetic hyperinnervation or denervation). Its synthesis and release are altered under different pathological conditions. Although NGF is well known for its survival effects on neurons, it is clear that these effects are more wide ranging. Recent studies reported both in vitro and in vivo evidence for beneficial actions of NGF on cardiomyocytes in normal and pathological hearts, including prosurvival and antiapoptotic effects. NGF also plays an important role in the crosstalk between the nervous and cardiovascular systems. It was the first neurotrophin to be implicated in postnatal angiogenesis and vasculogenesis by autocrine and paracrine mechanisms. In connection with these unique cardiovascular properties of NGF, we have provided comprehensive insight into its function and potential effect of NGF underlying heart sustainable/failure conditions. This review aims to summarize the recent data on the effects of NGF on various cardiovascular neuronal and non‐neuronal functions. Understanding these mechanisms with respect to the diversity of NGF functions may be crucial for developing novel therapeutic strategies, including NGF action mechanism‐guided therapies.

Keywords: NGF, Cardiovascular disease, Heart homeostasis, Neuroprotection, Metabotrophin

Introduction

Neurotrophins (NTs) are a highly homologous family of dimeric polypeptides, including nerve growth factor (NGF), brain‐derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), neurotrophin 3, and neurotrophin 4/5. Neurotrophic factor activity is mediated by binding to two types of cell surface receptors, the p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR) and receptor tyrosine kinases (Trks), which display high affinity and specificity for mature forms of NTs. 1 , 2 , 3 NGF preferentially binds to TrkA, BDNF, and neurotrophin 4/5 preferentially activate TrkB, and neurotrophin 3 acts via TrkC 3 , 4 and has lower affinity for TrkA and TrkB. 5 On the other hand, p75NTR, which lacks intrinsic enzymatic activity, 5 binds all NTs with similar affinity, including proneurotrophins. 1 , 6

The activity of NTs has been implicated in several functions, including axonal growth, synaptic plasticity, survival, myelination, and differentiation 7 , 8 in the central nervous system and peripheral nervous system. 9 Individual members of this family sustain differentiation and survival of distinct but overlapping populations of sensory and sympathetic neurons. 10 Strong evidence has emerged that NTs exert important cardiovascular functions, which largely exceed their roles in the neural regulation of heart function. 7 , 11 , 12 The first evidence of secretion of neurotrophic factors by heart cells was obtained in 1979, when Eberdal et al. showed that heart explants support neurite extension from sensory neurons in vitro. 13 The heart is innervated by sympathetic, parasympathetic, and sensory neurons derived from neural crest cells, all of which may require NTs during development. Indeed, NTs play an important role in the regulation of the sympathetic nervous system, acting as trophic survival factors but also as regulators of cardiac nerve outgrowth and axonal arborization. 14 , 15

Apart from their neuronal functions, NTs exert cardiovascular actions under both physiological and pathological conditions. 5 In early cardiovascular development, NTs and their receptors are essential for the appropriate formation of the heart and the regulation of vascular growth. In postnatal life, these factors control the survival of endothelial cells (ECs), vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), and cardiomyocytes and regulate angiogenesis and vasculogenesis by autocrine and paracrine mechanisms. 7 In connection with these unique cardiovascular properties of NTs, we have provided comprehensive insight into NGF functions and potential effects of NGF underlying heart sustainable/failure conditions. The angiogenic actions of NGF are mediated through direct effects on vascular ECs through regulation of the EC survival, proliferation, and migration 7 , 16 , 17 or indirectly by influencing the action of other endogenous growth factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). 18 , 19 Moreover, recent studies reported both in vitro and in vivo evidence for beneficial actions of NGF on cardiomyocytes in normal and pathological hearts, including pro‐survival and antiapoptotic effects. 7 , 14 , 20

Identification of the molecular mechanisms involved in the interactions between cardiomyocytes and other types of cells, such as neurons, and exploration of the extensive and diverse effects exerted by NGF within the cardiovascular niche may enhance our understanding of heart development, function, and disease. Cardiac innervation density generally reflects the levels of NGF produced by the heart. Furthermore, NGF supply from the innervation field influences the neuronal plasticity that allows the adult nervous system to modify its structure and function in response to stimuli. 21 Unbalanced heart innervation may occur in a wide variety of cardiovascular pathologies due to prevalent impairment of NGF expression by the myocardium (e.g. in diabetes 22 , 23 ), uncontrolled norepinephrine (NE) release by neurons [e.g. in heart failure (HF) 24 , 25 ] or local myocardial remodelling that follows ischaemic injury or NGF‐associated hypertrophy [i.e. myocardial infarction (MI) 14 , 24 , 26 , 27 ]. Therefore, we reviewed recent progress on the roles of NGF in cardiovascular development, function, and pathology as potent therapeutic targets for accelerating nerve regeneration and functional heart recovery by promoting myocardial neovascularization and inhibiting myocardial apoptosis.

Cardiac autonomic nervous system (sympathetic and parasympathetic)

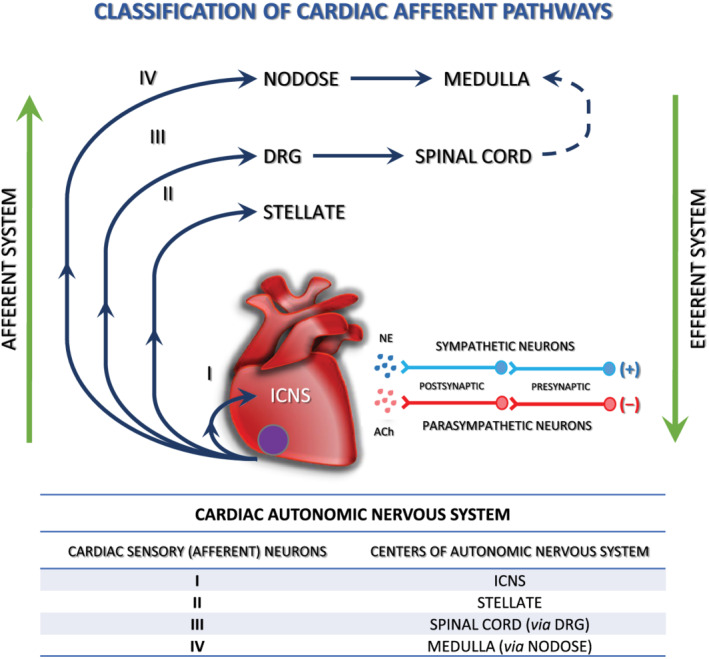

The heart is innervated by sympathetic, parasympathetic, and sensory neurons, all of which may require NTs during development and in postnatal life. Sympathetic innervation of the heart originates mainly from the right and left stellate ganglia (SG). Cardiac parasympathetic activity is mediated through the vagus nerve, which originates in the medulla 28 (Figure 1 ). Sympathetic axons innervate the atria, cardiac conduction system and ventricles, where they stimulate increased heart rate (chronotropy), conduction velocity (dromotropy), and contractility (inotropy) via NE activation of β1‐adrenergic receptors. 30 Cholinergic nerve fibres are most abundant in the sinoatrial and atrioventricular (AV) nodes, the atrial myocardium, and the ventricular conducting system. 30 , 31 Stimulation of cardiac parasympathetic nerves projecting to these regions leads to acetylcholine release, which evokes prominent bradycardia (slow heart rate), negative dromotropic responses (delayed AV conduction) and inotropy (decreased atrial contractility) via activation of postjunctional M2 muscarinic receptors. 30 , 32

Figure 1.

The cardiac autonomic nervous system—four cardiac sensory (afferent) pathways. Cardiac afferent neurons are located at multiple levels of the cardiac ANS, including intrinsic cardiac, stellate, middle cervical, mediastinal, nodose, and DRG. Bipolar neurons with cell bodies in the nodose ganglia and DRG have peripheral axons that project to the heart and central axons that synapse on second‐order neurons contained in the nucleus tractus solitarius of the medulla and the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, respectively. Spinal cord neurons project to and interact with neurons in higher centres such as the medulla. ACh, acetylocholine; DRG, dorsal root ganglion; ICNS, intrinsic cardiac nervous system; NE, norepinephrine; (+) sympathetic stimulation of the heart increases heart rate (positive chronotropy), inotropy, and conduction velocity (positive dromotropy); (−) parasympathetic stimulation of the heart has opposite effects. Sympathetic and parasympathetic effects on heart function are mediated by beta‐adrenoceptors and muscarinic receptors, respectively (figure reproduced from Rajendran 29 ).

Cardiac diseases such as chronic HF and MI are associated with abnormal cardiac autonomic control, including high levels of sympathetic activity, impaired parasympathetic control and subnormal arterial baroreflex sensitivity. 32 , 33 , 34 Sympathetic nerve sprouting and perturbed innervation are thought to play a role in arrhythmias. 28 , 35 In fact, the association between increased sympathetic nerve sprouting and an electrically remodelled myocardium may result in ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation (VF), and sudden cardiac death (SCD). 34 , 36 With the increasing understanding of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) and its role in the pathophysiology of cardiac diseases, autonomic modulation may play an important role in the treatment of various cardiovascular diseases. 37 The role of cardiac target‐derived factors as regulators of neuronal maturation, synaptic transmission, neuronal elongation, and axonal collateral sprouting has been well established. Changes in neurotrophic factor expression within the heart and vasculature, such as NGF, 34 , 38 contribute to neuronal remodelling (e.g. sympathetic hyperinnervation or denervation). These issues have been reviewed in detail in this paper and will be summarized here briefly.

Intrinsic cardiac nervous system

Heart innervation consists of extrinsic (nerves coming from the brain and thoracic paravertebral ganglia) and intrinsic ANS. The intrinsic cardiac nervous system (ICNS) that has been collectively called the heart's ‘little brain’ 39 is a neural network that consists of epicardial ganglionated plexi (GP) and the ligaments of Marshall. 40 , 41 The ganglia contain efferent postganglionic parasympathetic and sympathetic neurons, local circuit neurons, and afferent neurons 42 and act as an integrating network that processes afferent and efferent information involved in cardiac regulation. The function of GP is to modulate the autonomic interactions between the extrinsic and intrinsic ANS, which affects the sinus rate, AV conduction, refractoriness, and inducibility of atrial fibrillation (AF). 43 , 44 GPs are connected with each other by interconnecting neurons and create an extensive and complicated epicardial neural network. 40 , 43 , 45 , 46 , 47 . The number of cardiac ganglia is species‐dependent, ranging from 19 in the mouse 39 , 48 to over 800 in humans. 49 , 50 , 51 Ganglia contain 200 to 1000 neurons that innervate neighbouring cardiac structures and connect with sympathetic and parasympathetic nerve fibres from the extrinsic ANS. 43 , 52 They are surrounded by a fat pad composed of epicardial fat and ligament and are mostly positioned near the large vessels and posterior surface of the atrium, and 50% of all cardiac ganglia are located near the heart hilum, especially on the dorsal and dorsolateral surfaces of the left atrium. 39 , 40 , 43 , 51 , 52 , 53 For instance, the sinus node is primarily innervated by the right atrial GP, whereas the AV node is innervated by the inferior vena cava‐inferior atrial GP (also known as the inferior right or right inferior GP). 43

Cardiac ganglia are much more than a vagal relay station but are highly complex structures including efferent pre‐ganglionic and post‐ganglionic parasympathetic neurons and presumed putative post‐ganglionic sympathetic neurons, all of which all lie in close proximity to the sensory nerves. Ganglia show immunoreactivity to neuromodulators and neurotransmitters including, but not exclusively to choline acetyltransferase, vasoactive intestinal peptide, tyrosine hydroxylase, neuropeptide Y, neuronal nitric oxide synthase, synaptophysin, substance P, and calcitonin gene‐related peptide. 39 , 51 In contrast to the situation in the atria where cholinergic somata and nerve fibres dominate, the situation in the cardiac ventricles is reversed; there is a dominance of adrenergic nerve fibres within the left and right coronary subplexuses that innervate the ventricles 39 , 54 as well around the blood vessels. 39 , 55

Recently, it has been shown that atrial GP neurons are hypertrophied following HF, 51 , 56 providing evidence of anatomical and neurochemical changes following cardiac disease. 51 Not only do the intrinsic GPs participate in triggering and initiating AF, but they also modulate the electrical remodelling of the atria. 42 , 57 These changes would be expected to affect neuronal cell communication, detrimentally affecting ganglionic physiology, and could in part, explain the attenuation in GP neurotransmission following HF. 51 , 58 Clinical studies demonstrate that the dysfunction of the ICNS is associated with cardiac diseases, including AF and VF (Scherlag 39 , 59 , 60 , paragraph 4.2). The understanding of the human ICNS function and the way GPs are involved in cardiac control is increasingly important and may be crucial for reversing pathological autonomic imbalance and also for prophylactic and corrective treatments of heart disease.

Nerve growth factor/TrkA axis in cardiac development and physiology: The effect on different cell types within the cardiovascular niche

Proangiogenic effects

Increasing evidence has suggested that NGF plays an important role in the crosstalk between the nervous and cardiovascular systems. Accordingly, NGF is an essential factor in heart formation and exerts a variety of effects on peripheral tissues, including the vasculature. NGF was the first NT to be implicated in post‐natal angiogenesis and vasculogenesis by autocrine and paracrine mechanisms. 18 , 19 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 Raychaudhuri et al. 65 first described the proliferative action of NGF as a rapid phosphorylation of TrkA and through ERK1/2 activation in human dermal microvascular ECs. This was later confirmed in human umbilical vein ECs, human choroidal ECs, and rat brain ECs. 7 , 62 Through TrkA, NGF supports EC survival in vitro and in vivo and induces angiogenesis, which is, at least in part, mediated by increased VEGF‐A 18 , 19 , 36 , 66 and possibly VEGF receptors. 66 More interestingly, NGF apparently increases the ratio of large mature vessels and enhances the maturation of VEGF‐induced neovessels. 18 Additionally, NGF is a chemoattractant that is able to induce the migration of human and pig aortic ECs 1 , 7 , 61 and human aortic VSMCs, 7 , 67 , 68 which in turn leads to repair of the cardiovascular niche, thus exerting cardioprotective effects.

Nerve growth factor as a prosurvival factor for cardiomyocytes

It is worth noting that among its pleiotropic effects, one cardiovascular‐associated property of NGF is its autocrine prosurvival effect on cardiomyocytes. The secretion of neurotrophic factors by heart cells was first discovered in 1979 by Ebendal et al. 13 It is known that heart cells express and release NGF and express its receptor TrkA 7 , 11 , 20 , 69 ; through activation of this receptor, NGF triggers pro‐survival and antiapoptotic effects on cardiomyocytes in normal and pathological hearts in vitro and in vivo. 7 , 14 , 20 , 25 , 69 NGF overexpression is widely observed in cardiac pathologies (MI, diabetes, and etc.) and likely plays a beneficial role in cardiac cell survival and heart function 14 , 20 , 36 , 64 in contrast to normal, homeostatic cardiac tissue conditions in which cardiomyocytes exhibit very weak NGF expression and secretion. 14 , 36 , 70 , 71 Accordingly, in infarcted human hearts and in mice with infarcted hearts treated with an antibody against NGF or the TrkA inhibitor K252a, there was cardiomyocyte apoptosis and worsened cardiac function. 7 , 64 , 69 However, increased NGF levels obtained by either gene transfer or supplementation with recombinant NGF protein protected neonatal and adult cardiomyocytes from apoptosis and conferred immediate protection against injury caused by ischaemia/reperfusion in the heart, showing a potential therapeutic role for NGF in MI. 7 , 20 , 64 , 72 Various cardiac non‐neuronal cells, such as cardiomyocytes, 73 ECs, macrophages, and myofibroblasts, have been shown to participate in NGF secretion in cardiac tissue in pathophysiological situations. 11 , 14 , 26 , 69 , 70 , 74 , 75 , 76 The ability of fibroblasts to secrete NGF has already been reported in different fibroblastic cell lines. 14 , 77 In recent studies, clear evidence has been provided that healthy cardiac fibroblasts but not cardiomyocytes secrete high levels of NGF in physiological conditions. 14

Cardiac sympathetic nerve activity

Nerve growth factor is also a particularly important signalling molecule in the crosstalk between the nervous and cardiovascular systems. Sympathetic neurons in the first postnatal week compete for target‐derived NGF, as NGF levels in the immediate postnatal period are still subsaturated, with apoptosis occurring for those neurons that are unable to obtain sufficient levels of NGF. 78 , 79 NGF plays a critical role in sympathetic nerve growth, survival, differentiation, patterning, and synaptic strength. Moreover, the level of NGF in the adult heart corresponds to the extent of sympathetic innervation, 12 , 14 , 15 , 22 , 23 , 70 , 78 , 79 , 80 with the atria having higher protein and RNA levels than the ventricles. 78 , 80 The rapid effect of NGF on excitatory neurotransmission in vivo and in vitro appears to be due to a TrkA‐mediated presynaptic potentiation of NE release from sympathetic neurons via up‐regulation of tyrosine hydroxylase and dopamine‐β‐hydroxylase enzyme expression, which are involved in NE production. 81 , 82

Cardiac parasympathetic nerve activity

Nerve growth factor also increases the excitability of airway parasympathetic neurons and augments dendritic growth 78 , 83 ; however, sympathetic neurons are significant in promoting NGF synthesis by parasympathetic neurons. 84 Sympathetic and parasympathetic fibres are closely apposed in effector pacemaker and conduction areas, and maintenance of this spatial association occurs through NGF synthesis and release by cardiac ganglion (CG) neurons, which utilize NGF as an autocrine/paracrine factor. 75 , 78 In addition to regulating NGF expression, Hasan and Smith 75 demonstrated that the consequence of cardiac sympathectomy is a decrease in the cholinergic phenotype of rat CG neurons. While NGF is expressed by intact sympathetic innervation then allows for the formation of axo‐axonal synapses and reciprocal modulation of heart function. Although NGF exerts a powerful trophic effect on sympathetic neurons, its release from CG neurons may be critical for maintaining axo‐axonal apposition and parasympathetic inhibition of sympathetic function in congestive heart failure (CHF). 84 The relative expression of mature and pro‐NGF forms may also determine the extent of sympathetic‐parasympathetic axo‐axonal associations in CHF. 84

Cardiac sensory nerve activity

Nerve growth factor synthesis in the heart is also critical for the development of the sensory nervous system 12 , 22 because cardiac sensory nerves develop in parallel with the NGF synthesized in the heart, 12 , 22 , 23 and cardiac sensory innervation is rich both at epicardial sites and in the ventricular myocardium. 12 , 22 , 23 , 85 , 86 Cardiac nociceptive sensory nerves that are immunopositive for calcitonin gene‐related peptide, including the dorsal root ganglion and dorsal horn, are markedly impaired in NGF‐deficient mice, while cardiac‐specific overexpression of NGF rescues the heart from these deficits. 22 , 23 Moreover, NGF has been shown to regulate the expression of many neuropeptides in dorsal root ganglion neurons and modulate their sensitivity to noxious stimuli. 21 , 26 , 87 It was also found that the reduced NGF expression in diabetic hearts might explain the cardiac sensory denervation and neuropathy in diabetic mice, and overexpression of NGF in the hearts reversed sensory denervation and diabetic neuropathy in the mouse. 12 , 22 , 23 The cardiac sensory nervous system is responsible for pain perception and for the initiation of the protective cardiovascular response during MI. 86 , 88 Therefore, a main cause of SCD in diabetes is silent myocardial ischaemia (characterized by the loss of pain perception 12 , 89 ) caused by sensory nerve impairment, but according to the study by Ieda et al., NGF gene therapy of the heart rescues neuropathy in diabetic rats, 7 , 12 , 86 , 89 which improves the electrophysiological activity of cardiac afferent nerves during MI. 23

Taken together, these findings indicate that NGF, in addition to its eminent role in neuronal growth, survival, and neuroprotection, has direct impact on the cardiovascular system in terms of pro‐survival and proangiogenic effects. This unique crosstalk between the cardiovascular and nervous systems with respect to the many functions of NGF could be useful in designing new preventive and therapeutic strategies for vascular and heart dysfunction.

The role of nerve growth factor in response to pathological cardiac stress

Ischaemic injury/myocardial infarction

Angiogenesis

While NGF is expressed in normal hearts, 70 , 71 its synthesis and release are altered under different pathological conditions. NGF plays an important role in post‐infarction remodelling. 90 Beyond its actions on cardiomyocytes, NGF exerts beneficial actions via vascular effects, including the stimulation of angiogenesis and pro‐survival actions following MI 20 , 25 , 69 , 72 and increasing the density of both capillaries and mature vessels (such as arterioles) in response to hindlimb ischaemia 1 , 16 , 18 , 25 , 91 and after arterial balloon injury in rats in which the increased expression level of NGF and TrkA persist during neointimal formation. 7 , 67 Similarly, Diao et al. 92 found significantly milder muscle atrophy, EC proliferation, and angiogenesis after NGF and VEGF gene transfection in hindlimb ischaemic mice, suggesting the angiogenic functions of NGF and VEGF. Moreover, type 1 diabetes down‐regulates the levels of NGF and TrkA in ischaemic skeletal muscles and concomitantly induces p75NTR expression in capillary ECs, 17 , 20 suggesting that p75NTR is responsible for diabetes‐induced impairment in neovascularization of ischaemic limb muscles. 7 In contrast to Trk actions, ligand (NGF and pro‐NGF)‐dependent activation of p75NTR, which is increased following vascular injury (in pathological conditions such as diabetes or atherosclerosis 17 , 67 , 93 ), reportedly induces EC 7 , 9 , 36 , 73 , 94 and neointimal smooth muscle cell death. 1 , 7 , 95 Interestingly, rather than initiating apoptosis of diabetic ECs via p75NTR, NGF supplementation down‐regulates p75NTR expression by a mechanism that has not yet been clarified and promotes EC survival and vascular regeneration. 7 , 17 Studies examining the angiogenic actions of NGF have demonstrated that NGF gene delivery to the infarcted hearts of mice and rats increase capillary density and inhibit EC apoptosis in the peri‐infarct areas, 7 ameliorate cardiomyocyte survival and improve myocardial blood flow. 20 , 69 , 90 Furthermore, exogenous administration of recombinant mature NGF in the ischaemic rodent hindlimb model induced a marked increase in arteriole length density. 1 , 16 , 62 , 68 , 91

Sympathetic nerve remodelling

Myocardial infarction‐associated complications are correlated with anatomical (myocardial, vascular, and neural) and cardiac electrical remodelling initiated by the infarction. As a member of the NT family, NGF is critical for the differentiation, survival, and synaptic activity of sympathetic nerves during human development and after cardiac injury. 15 , 90 In MI, persistent up‐regulation of NGF expression (produced via macrophages and myofibroblasts) is observed within the ischaemic area of infarcted hearts, underscoring its involvement in post‐infarction sympathetic nerve sprouting and regeneration. 14 , 23 , 26 , 36 , 74 , 78 , 96 , 97 Endothelin‐1, a key regulator of NGF expression in cardiomyocytes and a cardiac hypertrophic factor, 11 , 78 is strongly induced in pathological conditions, and the endothelin‐1/NGF pathway may also be involved in NGF up‐regulation and nerve regeneration after MI. 11 , 23 , 98 After MI, despite the increased expression of NGF‐induced sympathetic hyperinnervation, this alternation may also represent an adaptive mechanism by which the heart tries to maintain ventricular contractility at the cost of eventually triggering life‐threatening ventricular arrhythmias (VA), 24 , 26 , 27 , 99 VF, and SCD. 23 , 99 Novel findings indicate that modulation of NGF expression may regulate sympathetic innervation patterns, providing potential access points for novel therapeutic strategies to prevent lethal arrhythmias and SCD. Hu et al. 90 revealed that targeted intracardiac administration of NGF small interfering RNA in a rat MI model reduced nerve sprouting, decreased sympathetic nerve density, attenuated angiogenesis, augmented infarct size, and exacerbated cardiac dysfunction. Intriguingly, NGF may also modulate beta‐adrenergic receptors (β‐AR) expression in cardiomyocytes, which a finding that has possible ramifications for arrhythmia generation because β‐AR expression is increased in some cardiac pathological states. 78 , 84 , 100 , 101 , 102 Interestingly, while NGF stimulates axonal growth, its precursor pro‐NGF triggers axon degeneration and may be involved in post‐MI denervation. 94

Oxidative stress

Previous studies showed that the mechanisms underlying myocardial ischaemic injury might be associated with calcium overload, mitochondrial dysfunction, 30 , 103 , 104 increased reactive oxygen species (ROS), 98 , 103 activation and adhesion of neutrophils (increased levels of NGF protein may attract TrkA‐expressing neutrophils/monocytes into the border zone 26 ), 36 , 103 complement activation, endothelial dysfunction, cytokine release, or cellular apoptosis. 26 , 103 , 105 The NGF promoter contains activator protein‐1, which is subjected to redox regulation through its conserved cysteine residue. 98 Peroxynitrite induces activator protein‐1 activation, which in turn activates the NGF promoter and enhances the transcription of NGF. 98 According to numerous studies, in the border zone of the myocardium during reperfusion NGF protects sensory and sympathetic neurites against ROS, which are deleterious to cardiac cells. 26 , 97 , 106 , 107 Abe et al. showed that intracoronary administration of NGF during brief episodes of ischaemia can protect against post‐ischaemic sympathetic dysfunction. 26 , 97 It might be speculated that, similarly to brain insult, 26 , 108 up‐regulation of NGF within the failing heart can induce the activation of ROS‐detoxifying enzymes, 108 and ameliorate ongoing neuronal injury by suppressing the actions of ROS in nerve terminals 26 ; however, this mechanism has not been clearly explained and verified. Contrary to this mechanism, it is a well‐investigated phenomenon that oxidative stress is increased and has a critical role in sympathetic neural remodelling (hyperinnervation) following MI and augments the expression of NGF in infarcted rat hearts 99 (more in paragraph 4.2). The inhibition of the superoxide generation decreased the expression of NGF and attenuated sympathetic neural remodelling following MI. 109 , 110 , 111

Autophagy

Many studies have also suggested that autophagy plays an adaptive role in protecting cardiomyocytes after ischaemic injury and suppresses the acceleration of HF. 103 , 112 In a recent study, Wang et al. 103 found that NGF improves myocardial ischaemia reperfusion injury in a mouse model and that the protective effect of NGF is associated with increased autophagy‐mediated ubiquitination.

Collectively, up‐regulation of NGF expression in post‐infarcted hearts exerts both harmful (pro‐arrhythmia effects, SCD, and fibrillation) and protective effects, such as myocardial and vascular repair, diminished oxidative stress, and autophagy stimulation.

Ventricular and atrial arrhythmias

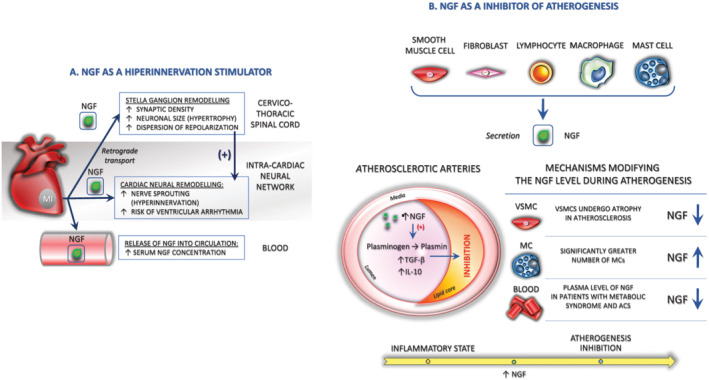

Nerve growth factor is a key cytokine thought to promote autonomic nerve sprouting in the ventricle 96 , 113 , 114 and atrium, 113 , 115 , 116 and its production in target organs determines the density of innervation by the sympathetic nervous system. 96 , 117 Cardiac sympathetic left stellate ganglion (LSG) activity increases markedly before VA onset in an ischemia model, 118 and the inhibition of LSG activity effectively reduces the incidence of VA. 118 , 119 , 120 , 121 Accordingly, it was recently reported that non‐invasive light‐emitting diode therapy might significantly reduce both sympathetic activation, manifested by a decrease in LSG neural activity and expression of NGF, and inflammatory response in the myocardium, thus reducing the incidence of acute MI‐induced VAs. 121 Cao et al. 122 demonstrated that heterogeneous cardiac nerve sprouting and sympathetic hyperinnervation play important roles in arrhythmogenesis and SCD in both human patients and the animal models of MI. In a canine post‐MI model, they demonstrated that the induction of nerve sprouting by infusion of NGF into the LSG resulted in an increased incidence of ventricular tachycardia and VF. 96 , 123 Furthermore, diffuse ventricular sympathetic hyperinnervation following MI is secondary to the local secretion of NGF in the peri‐infarct region. 96 , 113 , 114 Retrograde transport of NGF by sympathetic nerve fibrils from the infarcted region to the SG results in hypertrophy of postganglionic neurons in SG 80 , 96 (Figure 2A ). This, in turn, leads to the diffuse sympathetic hyperinnervation of the left ventricle at regions remote from the infarct region, thereby promoting VA. 113 Nguyen et al. 114 also reported that MI results in an increased serum NGF level and can exert trophic effects in inducing neural remodelling in the SG after MI in rabbits. Nerve sprouting and sympathetic hyperinnervation were associated with the dispersion of repolarization, changes in calcium currents, and increased VF incidence. Collectively, this evidence indicates that heterogeneous remodelling and hyperadrenergic innervation are likely to play significant adverse roles in the increased risk of life‐threatening arrhythmias after MI. 123 Therefore, new therapeutic approaches to abolish an unbalanced crosstalk between SG and infarcted myocardium might prevent sympathetic neural remodelling and cardiac cell dysfunction.

Figure 2.

The role of NGF in response to pathological cardiac stress. (A). NGF induces complex, autonomic changes occurring secondary to acute myocardial infarction, like the sympathetic hyperinnervation and hypertrophy of postganglionic neurons in SG. These effects may promote arrhythmias that may be responsible for sudden cardiac death. (B). NGF exerts a protective effect on tissue repair like vascular endothelial dysfunction during atherogenesis (detailed description in the text). MC, mast cell; NGF, nerve growth factor

There has also been increasing evidence that abnormalities of the ANS, which that includes sympathetic, parasympathetic, and intrinsic neural network are involved in the pathogenesis of AF. 45 , 124 The cardiac ANS plays an essential role in epicardial GP regulation of AF onset and progression. 40 AF‐associated oxidative stress, 42 , 125 may cause cardiac nerve injury, which triggers the re‐expression of NGF or other neurotrophic factors in the non‐neuronal cells around the site of injury. 42 , 102 NGF over‐expression is associated with myocardial hyperinnervation and atrial fibrosis, 102 , 126 whereas increase in atrial sympathetic innervation contribute to the generation and maintenance of AF by exerting significant effects on automaticity, refractoriness, and conduction velocity. 43 , 102 , 113 , 127 , 128 It is known that increased parasympathetic signalling is a key contributor to the refractory period shortening in the atrium. Accordingly, the activity of GP, which provides the majority of parasympathetic innervation to the atria, is increased in the animal models of AF, 113 , 129 and the heightened vagal tone was shown to precede the onset of AF paroxysms in patients. 113 , 130 Similarly, as demonstrated in dogs, there is sympathetic hyperinnervation in the fibrillating atrium, with evidence of the heightened sympathetic discharge from SG with rapid atrial pacing‐induced AF. 113 , 115 , 127 , 129 Gussak et al. 113 explain that NGF released from fibrillating atrial myocytes in the left atrial appendage is taken up by parasympathetic and sympathetic nerve fibrils in the atrial myocardium and is retrogradely transported to the atrial GPs and the SG, respectively, thereby leading to hypertrophy of postganglionic neurons in these structures. This hypertrophy of the ‘parent’ ganglia then leads to the diffuse parasympathetic and sympathetic hyperinnervation through all regions of the left atrium. These findings suggest that dysregulation and imbalance of autonomic nervous function are key factors regulating the occurrence and persistence of AF. Consequently, damage to the GP network could also reveal the inhibition of the onset and progression of the AF. 40

Recent years have seen the emergence of ablation as a major therapeutic advance in the treatment of AF. Unfortunately, both pharmacological and ablative therapies for AF have suboptimal efficacy in patients with persistent AF. 113 , 131 Moreover, partial vagal denervation may facilitate rather than prevent vagally mediated AF by increasing the heterogeneity of refractoriness within the atria. 43 , 128 Numerous studies have demonstrated that myocardial injuries, such as the previously mentioned MI or radiofrequency catheter ablation, lead to cardiac nerve sprouting and sympathetic hyperinnervation in the animal models, 102 , 122 which has been known to be related to the rises of the level of NGF. 43 , 96 , 102 , 113 , 132 Radiofrequency catheter ablation for AF increases the plasma concentration of NGF. High plasma levels of NGF were found to be associated with high sympathetic nerve activity estimated by heart rate variability and high number of atrial premature contractions after ablation. 102

To summarize, the heterogeneity in afferent neural signals, along with the remodelling of convergent neurons, may play an important role in the genesis of arrhythmias and progression to HF. 133 Due to the complexity of the pathogenesis underlying AF, there are few effective therapies available. 40 Therefore, a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying the genesis and maintenance of the AF disease state and the NGF role in the creation of electrical/structural remodelling in the fibrillating atrium would facilitate the development of newer, dedicated therapies for this arrhythmia.

Congestive heart failure

A key component of altered sympathetic nervous system pathology is a reduction in sympathetic nerve density, which is associated with a reduction in the tissue levels of NGF both in experimental animals and humans. 73 , 134 In CHF, NGF protein expression is decreased in ventricles, resulting in reduced trophic support for sympathetic neurons. 84 , 100 , 134 , 135 Functionally, sympathetic nerves in CHF convert from a balanced NE synthesis, release, and reuptake system to the one that predominantly releases NE, resulting in excessive myocardial stimulation and catecholamine toxicity. 84 , 135 Govoni et al. 36 explained that the reduction in NGF levels may be caused by the fact that high catecholamine levels inhibit NGF expression. Pro‐NGF has been shown to promote pruning, degeneration, and apoptosis of sympathetic axons in the relative absence of the mature form 84 , 136 , 137 and a reduction in mature NGF, accompanied by stable levels of the pro‐form, would potentially decrease sympathetic‐parasympathetic apposition in the failing heart and disrupt autonomic crosstalk. 78 , 84 Accordingly, changes in mature NGF and pro‐NGF within CG neurons from CHF rats in a study by Hasan and Smith 84 were similar to those observed after sympathectomy, suggesting a common mechanism is at play. Similarly, during the progression of HF, HF induced by NE infusion leads to a decline in NGF expression and production by cardiomyocytes, 24 , 25 , 78 , 100 which is mediated by alpha‐1‐adrenergic receptor activation. 24 , 36 , 70 Intriguingly, while β‐ARs have been shown to promote NGF expression, alpha‐1‐adrenergic receptor stimulation promotes an attenuation of NGF in the heart. 84 , 100 , 101 This may be favoured by increased apoptosis of myocytes 20 , 24 and widespread myocardial denervation 36 , 70 , 78 , 100 , 101 as a ramification of chronic elevated adrenergic tone and mechanical stretch. Moreover, mechanical stretching is a pathophysiological stimulus that is correlated with several cardiac diseases, such as MI, HF, or arterial hypertension, and Rana et al. discovered that in cardiomyocytes, cellular stretching leads to a decrease in NGF mRNA and protein expression. 24 , 36

Atherosclerosis/acute coronary syndrome

Basic and clinical studies indicate that atherosclerosis is an inflammatory‐fibroproliferative disease initiated by endothelial dysfunction and develops as a result of a complex interaction between various growth factors/cytokines, VSMCs, and immune cells. 138 NGF is secreted by both types of cells that participate in the inflammatory process, structural cells (i.e. ECs, smooth muscle cells, and fibroblasts) and cells of the haemopoietic immune system that infiltrate into the site of inflammation, such as mast cells (MCs), macrophages, and lymphocytes. 36 , 76 , 139 In fact, NGF mediates many inflammatory and autoimmune states in conjunction with increased accumulation of MCs 21 , 140 that appear to be involved in neuroimmune interactions and tissue inflammation. 139 Because MCs are known to be a cellular component of the coronary artery and these cells not only respond to NGF action, 141 , 142 but also produce and release NGF, 141 , 143 the presence and distribution of MCs in atherosclerotic and control coronaries have been also examined. 141 NGF, acts as a chemoattractant, thereby causing an increase in the number of MCs as well as their degranulation, 144 , 145 inducing the release of various mediators from MC. 145 Interestingly, NGF receptors on MCs act as autoreceptors, regulating MC NGF synthesis and release, while at the same time being sensitive to NGF from the environment. 144 The fact that the number of MCs increases, whereas the availability of NGF decreases, suggests that MCs do not play a decisive role in NGF synthesis in atherosclerotic vascular tissue. 146 However, is it still open to further research to determine whether these MC populations, via their potential to synthesize and release NGF, attempt to compensate for the reduced NGF in the coronary wall and prevent atherosclerosis. 141

Accordingly, recent studies have reported the potential importance of NTs in atherosclerosis and related disorders, 67 , 147 which leads to the hypothesis that NTs undergo significant changes in acute coronary syndromes (ACS), the major clinical complications of coronary artery disease and atherosclerosis. 147 Chaldakov et al. 138 were the first to demonstrate that the level of NGF was significantly reduced in human coronary arteries with advanced atherosclerotic lesions. These results also revealed that the coronary adventitia of atherosclerotic subjects displayed an overexpression of p75NTR immunoreactivity 67 , 93 and a significantly greater number of MCs and vasa vasorum than those of controls. 138 , 139 , 148 There is a possibility that the secretion of NGF in pathological tissues is reduced because VSMCs, which are the main vascular source of NGF, 138 , 149 undergo atrophy in atherosclerosis and/or the NGF turnover is higher in atherosclerotic arteries than in normal arteries. 138 It has been reported that NGF derived from MCs and T lymphocytes exerts a protective effect on tissue repair. 138 , 150 , 151 Similarly, Chaldakov et al. 152 recently reported that the plasma levels of NGF and BDNF are significantly reduced in patients with metabolic syndrome and ACS.

The decreased vascular tissue content of NGF in human coronary atherosclerosis suggests that a metabolic imbalance due to the reduction in NT availability may operate in the pathogenesis of obesity and related metabolic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and atherosclerosis. Important lines of evidence to support this hypothesis include the following: (1) NGF shares a striking structural homology with proinsulin 152 and exerts certain effects on lipid metabolism and energy homeostasis 152 , 153 ; (2) pancreatic beta cells secrete NGF and express its receptor, TrkA, and NGF enhances glucose‐induced insulin secretion via an autocrine/paracrine pathway (it is possible that pancreatic NGF may be exported to the bloodstream where it functions as an endocrine messenger; decreased NGF serum levels was observed in diabetic patients 154 ) 152 , 154 , 155 ; (3) NGF up‐regulates the expression of low‐density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor‐related protein, 138 , 152 , 156 which is a member of the LDL receptor gene family whose malfunction is causally related to atherosclerosis 138 , 152 ; (4) NGF inhibits glucose‐induced down‐regulation of caveolin‐1, which plays a critical role in TrkA and p75NTR signalling, LDL receptor signalling, and lipid metabolism and obesity 152 ; and (5) NGF, through its serine protease activity, converts plasminogen into plasmin, 138 , 157 which is a crucial factor for the activation of transforming growth factor‐beta (a key inhibitor of atherogenesis), strongly up‐regulates interleukin‐10, 138 , 158 another inhibitor of atherogenesis, and induces the expression of urokinase plasminogen activator receptor 138 , 159 (Figure 2B ).

In summary, the studies carried out in the past three decades have revealed that the key NT NGF not only stimulates nerve growth and survival but also exerts trophic effects on ECs, acting as angiogenic factor, and is involved in the maintenance of glucose, lipid and energy homeostasis, and regulation of pancreatic beta cells and the cardiovascular system, and is thus designated metabotrophin (from the Greek word meaning ‘nutritious for metabolism’). 155 , 160 Indeed, NGF may operate as a metabotrophin, which means that it is involved in the maintenance of cardiometabolic homeostasis (glucose and lipid metabolism as well as energy balance, cardioprotection, and wound healing), and the reduction in NGF availability and/or utilization may play a critical role in the pathogenesis of cardiometabolic dysfunctions, such as coronary artery disease and atherosclerosis.

Altogether, NGF is an important factor in the degenerative and regenerative processes that occur in the heart. NGF suppression is related to abolishment of the angiogenic repair process, elevation of cardiomyocyte apoptosis and generally worsened cardiac function. Understanding these complex cell–cell interactions and molecular mechanisms leading to NGF‐mediated cell dysfunction might provide insight into new therapeutic approaches and treatments for cardiovascular diseases.

Conclusions

Although NTs are well known for their survival effects on neurons, it is clear that their properties are more wide ranging. Here, we focused on outlining the importance of the first discovered member of this class of growth factors, NGF, in determining and maintaining cardiovascular phenotypes and homeostasis. Strong evidence has emerged that NGF exerts important cardiovascular activities and unique ‘tropisms’ to many cells within the cardiovascular niche. In addition to its neuronal functions, NGF is an essential factor in heart formation and triggers a variety of effects on peripheral tissues, including the vasculature and ECs and regulates angiogenesis and vasculogenesis. This molecule contributes to the maintenance of proper heart rate, conduction velocity, and contractility or, conversely, heart function disruption and disease, which depends on its concentration within the niche; its synthesis and release are altered under different pathological conditions. The altered presence of NGF and/or its receptors may be involved in the pathogenesis of vascular/heart diseases, including hypertension, MI, HF, cardiac hypertrophy, atherosclerosis, or ACS. Individual differences of NGF expression might also be responsible for differential nerve sprouting, heterogeneous remodelling and hyperadrenergic innervation and susceptibility to arrhythmia. Identification of the molecular mechanisms involved in the interactions between cardiomyocytes and other types of cells and exploration of the extensive and diverse effects exerted by NGF within the cardiovascular niche may enhance our understanding of heart development, function, and disease and may lead to the design of new effective therapeutic strategies. A further challenge is represented by the increasing knowledge of the role of NGF in vascular, immune, metabolic, or nervous system regulation, opening an interesting field for the development of innovative NGF‐based therapies in cardiovascular diseases and a novel and demanding clinical aspect of the use of NGF.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

The project was financed from the programme of the Minister of Science and Higher Education under the name ‘Regional Initiative of Excellence’ in 2019–2022 project number 002/RID/2018/19 amount of financing 12 000 000 PLN.

Author contributions

E.P.S. searched of the literature, wrote, drafted, and revised of the manuscript and prepared figure. B.M. contributed to all aspects of the manuscript preparation, from conception and design, to review and correction of the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pius‐Sadowska, E. , and Machaliński, B. (2021) Pleiotropic activity of nerve growth factor in regulating cardiac functions and counteracting pathogenesis. ESC Heart Failure, 8: 974–987. 10.1002/ehf2.13138.

References

- 1. Kermani P, Hempstead B. Brain‐derived neurotrophic factor: a newly described mediator of angiogenesis. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2007; 17: 140–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Huang EJ, Reichardt LF. Trk receptors: roles in neuronal signal transduction. Annu Rev Biochem 2003; 72: 609–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Huang EJ, Reichardt LF. Neurotrophins: roles in neuronal development and function. Annu Rev Neurosci 2001; 24: 677–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arévalo JC, Wu SH. Neurotrophin signaling: many exciting surprises! Cell Mol Life Sci 2006; 63: 1523–1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cristofaro B, Stone OA, Caporali A, Dawbarn D, Ieronimakis N, Reyes M, Madeddu P, Bates DO, Emanueli C. Neurotrophin‐3 is a novel angiogenic factor capable of therapeutic neovascularization in a mouse model of limb ischemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2010; 30: 1143–1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hempstead BL. The many faces of p75NTR. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2002; 12: 260–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Caporali A, Emanueli C. Cardiovascular actions of neurotrophins. Physiol Rev 2009; 89: 279–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lu B, Pang PT, Woo NH. The yin and yang of neurotrophin action. Nat Rev Neurosci 2005; 6: 603–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kim H, Li Q, Hempstead BL, Madri JA. Paracrine and autocrine functions of brain‐derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and nerve growth factor (NGF) in brain‐derived endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 2004; 279: 33538–33546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Skaper SD. The biology of neurotrophins, signalling pathways, and functional peptide mimetics of neurotrophins and their receptors. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 2008; 7: 46–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ieda M, Fukuda K, Hisaka Y, Kimura K, Kawaguchi H, Fujita J, Shimoda K, Takeshita E, Okano H, Kurihara Y, Kurihara H, Ishida J, Fukamizu A, Federoff HJ, Ogawa S. Endothelin‐1 regulates cardiac sympathetic innervation in the rodent heart by controlling nerve growth factor expression. J Clin Invest 2004; 113: 876–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ieda M, Kanazawa H, Ieda Y, Kimura K, Matsumura K, Tomita Y, Yagi T, Onizuka T, Shimoji K, Ogawa S, Makino S, Sano M, Fukuda K. Nerve growth factor is critical for cardiac sensory innervation and rescues neuropathy in diabetic hearts. Circulation 2006; 114: 2351–2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ebendal T, Belew M, Jacobson CO, Porath J. Neurite outgrowth elicited by embryonic chick heart: partial purification of the active factor. Neurosci Lett 1979; 14: 91–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mias C, Coatrieux C, Denis C, Genet G, Seguelas MH, Laplace N, Rouzaud‐Laborde C, Calise D, Parini A, Cussac D, Pathak A, Sénard JM, Galés C. Cardiac fibroblasts regulate sympathetic nerve sprouting and neurocardiac synapse stability. PLoS ONE 2013; 8: e79068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Snider WD. Functions of the neurotrophins during nervous system development: what the knockouts are teaching us. Cell 1994; 77: 627–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Emanueli C, Salis MB, Pinna A, Graiani G, Manni L, Madeddu P. Nerve growth factor promotes angiogenesis and arteriogenesis in ischemic hindlimbs. Circulation 2002; 106: 2257–2262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Salis MB, Graiani G, Desortes E, Caldwell RB, Madeddu P, Emanueli C. Nerve growth factor supplementation reverses the impairment, induced by type 1 diabetes, of hindlimb post‐ischaemic recovery in mice. Diabetologia 2004; 47: 1055–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Asanome A, Kawabe J, Matsuki M, Kabara M, Hira Y, Bochimoto H, Yamauchi A, Aonuma T, Takehara N, Watanabe T, Hasebe N. Nerve growth factor stimulates regeneration of perivascular nerve, and induces the maturation of microvessels around the injured artery. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2014; 443: 150–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nico B, Mangieri D, Benagiano V, Crivellato E, Ribatti D. Nerve growth factor as an angiogenic factor. Microvasc Res 2008; 75: 135–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Caporali A, Sala‐Newby GB, Meloni M, Graiani G, Pani E, Cristofaro B, Newby AC, Madeddu P, Emanueli C. Identification of the prosurvival activity of nerve growth factor on cardiac myocytes. Cell Death Differ 2008; 15: 299–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Aloe L, Rocco ML, Bianchi P, Manni L. Nerve growth factor: from the early discoveries to the potential clinical use. J Transl Med 2012; 10: 239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ieda M. Heart development and regeneration via cellular interaction and reprogramming. Keio J Med 2013; 62: 99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ieda M, Fukuda K. New aspects for the treatment of cardiac diseases based on the diversity of functional controls on cardiac muscles: the regulatory mechanisms of cardiac innervation and their critical roles in cardiac performance. J Pharmacol Sci 2009; 109: 348–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rana OR, Saygili E, Meyer C, Gemein C, Krüttgen A, Andrzejewski MG, Ludwig A, Schotten U, Schwinger RH, Weber C, Weis J, Mischke K, Rassaf T, Kelm M, Schauerte P. Regulation of nerve growth factor in the heart: the role of the calcineurin‐NFAT pathway. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2009; 46: 568–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Saygili E, Pekassa M, Rackauskas G, Hommes D, Noor‐Ebad F, Gemein C, Zink MD, Schwinger RH, Weis J, Marx N, Schauerte P, Rana OR. Mechanical stretch of sympathetic neurons induces VEGF expression via a NGF and CNTF signaling pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2011; 410: 62–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hiltunen JO, Laurikainen A, Väkevä A, Meri S, Saarma M. Nerve growth factor and brain‐derived neurotrophic factor mRNAs are regulated in distinct cell populations of rat heart after ischaemia and reperfusion. J Pathol 2001; 194: 247–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Miwa K, Lee JK, Takagishi Y, Opthof T, Fu X, Hirabayashi M, Watabe K, Jimbo Y, Kodama I, Komuro I. Axon guidance of sympathetic neurons to cardiomyocytes by glial cell line‐derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF). PLoS ONE 2013; 8: e65202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Franciosi S, Perry FKG, Roston TM, Armstrong KR, Claydon VE, Sanatani S. The role of the autonomic nervous system in arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. Auton Neurosci 2017; 205: 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rajendran PS. Neural control of cardiac function in health and disease. In Dilsizian V., Narula J., eds. Atlas of Cardiac Innervation, 1st ed. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2017. p 13–35. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Habecker BA, Anderson ME, Birren SJ, Fukuda K, Herring N, Hoover DB, Kanazawa H, Paterson DJ, Ripplinger CM. Molecular and cellular neurocardiology: development, and cellular and molecular adaptations to heart disease. J Physiol 2016; 594: 3853–3875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hoover DB, Ganote CE, Ferguson SM, Blakely RD, Parsons RL. Localization of cholinergic innervation in guinea pig heart by immunohistochemistry for high‐affinity choline transporters. Cardiovasc Res 2004; 62: 112–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ng GA. Neuro‐cardiac interaction in malignant ventricular arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death. Auton Neurosci 2016; 199: 66–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Doppalapudi H, Jin Q, Dosdall DJ, Qin H, Walcott GP, Killingsworth CR, Smith WM, Ideker RE, Huang J. Intracoronary infusion of catecholamines causes focal arrhythmias in pigs. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2008; 19: 963–970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Swissa M, Zhou S, Gonzalez‐Gomez I, Chang CM, Lai AC, Cates AW, Fishbein MC, Karagueuzian HS, Chen PS, Chen LS. Long‐term subthreshold electrical stimulation of the left stellate ganglion and a canine model of sudden cardiac death. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004; 43: 858–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Vaseghi M, Lux RL, Mahajan A, Shivkumar K. Sympathetic stimulation increases dispersion of repolarization in humans with myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2012; 302: H1838–H1846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Govoni S, Pascale A, Amadio M, Calvillo L, D'Elia E, Cereda C, Fantucci P, Ceroni M, Vanoli E. NGF and heart: is there a role in heart disease? Pharmacol Res 2011; 63: 266–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Durães Campos I, Pinto V, Sousa N, Pereira VH. A brain within the heart: a review on the intracardiac nervous system. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2018; 119: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yang M, Zhang S, Liang J, Tang Y, Wang X, Huang C, Zhao Q. Different effects of norepinephrine and nerve growth factor on atrial fibrillation vulnerability. J Cardiol 2019; 74: 460–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wake E, Brack K. Characterization of the intrinsic cardiac nervous system. Auton Neurosci 2016; 199: 3–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Li Y, Lu YM, Zhou XH, Zhang L, Li YD, Zhang JH, Xing Q, Tang BP. Increase of autonomic nerve factors in epicardial ganglionated plexi during rapid atrial pacing induced acute atrial fibrillation. Med Sci Monit 2017; 23: 3657–3665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kapa S, Venkatachalam KL, Asirvatham SJ. The autonomic nervous system in cardiac electrophysiology: an elegant interaction and emerging concepts. Cardiol Rev 2010; 18: 275–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yu Y, Wei C, Liu L, Lian AL, Qu XF, Yu G. Atrial fibrillation increases sympathetic and parasympathetic neurons in the intrinsic cardiac nervous system. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2014; 37: 1462–1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Choi EK, Zhao Y, Everett TH, Chen PS. Ganglionated plexi as neuromodulation targets for atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2017; 28: 1485–1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hou Y, Scherlag BJ, Lin J, Zhang Y, Lu Z, Truong K, Patterson E, Lazzara R, Jackman WM, Po SS. Ganglionated plexi modulate extrinsic cardiac autonomic nerve input: effects on sinus rate, atrioventricular conduction, refractoriness, and inducibility of atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 50: 61–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Khan AA, Lip GYH, Shantsila A. Heart rate variability in atrial fibrillation: the balance between sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system. Eur J Clin Invest 2019; 49: e13174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zhou X, Wang Z, Huang B, Yuan S, Sheng X, Yu L, Meng G, Wang Y, Po SS, Jiang H. Regulation of the NRG1/ErbB4 pathway in the intrinsic cardiac nervous system is a potential treatment for atrial fibrillation. Front Physiol 2018; 9: 1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lazzara R, Scherlag BJ, Robinson MJ, Samet P. Selective in situ parasympathetic control of the canine sinoatrial and atrioventricular nodes. Circ Res 1973; 32: 393–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rysevaite K, Saburkina I, Pauziene N, Noujaim SF, Jalife J, Pauza DH. Morphologic pattern of the intrinsic ganglionated nerve plexus in mouse heart. Heart Rhythm 2011; 8: 448–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pauza DH, Skripka V, Pauziene N, Stropus R. Morphology, distribution, and variability of the epicardiac neural ganglionated subplexuses in the human heart. Anat Rec 2000; 259: 353–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Armour JA. Intrinsic cardiac neurons involved in cardiac regulation possess alpha 1‐, alpha 2‐, beta 1‐ and beta 2‐adrenoceptors. Can J Cardiol 1997; 13: 277–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Brack KE. The heart's ‘little brain’ controlling cardiac function in the rabbit. Exp Physiol 2015; 100: 348–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Armour JA, Murphy DA, Yuan BX, Macdonald S, Hopkins DA. Gross and microscopic anatomy of the human intrinsic cardiac nervous system. Anat Rec 1997; 247: 289–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Po SS, Nakagawa H, Jackman WM. Localization of left atrial ganglionated plexi in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2009; 20: 1186–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Pauziene N, Alaburda P, Rysevaite‐Kyguoliene K, Pauza AG, Inokaitis H, Masaityte A, Rudokaite G, Saburkina I, Plisiene J, Pauza DH. Innervation of the rabbit cardiac ventricles. J Anat 2016; 228: 26–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Pauza DH, Saburkina I, Rysevaite K, Inokaitis H, Jokubauskas M, Jalife J, Pauziene N. Neuroanatomy of the murine cardiac conduction system: a combined stereomicroscopic and fluorescence immunohistochemical study. Auton Neurosci 2013; 176: 32–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Singh S, Sayers S, Walter JS, Thomas D, Dieter RS, Nee LM, Wurster RD. Hypertrophy of neurons within cardiac ganglia in human, canine, and rat heart failure: the potential role of nerve growth factor. J Am Heart Assoc 2013; 2: e000210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Nishida K, Maguy A, Sakabe M, Comtois P, Inoue H, Nattel S. The role of pulmonary veins vs. autonomic ganglia in different experimental substrates of canine atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res 2011; 89: 825–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bibevski S, Dunlap ME. Ganglionic mechanisms contribute to diminished vagal control in heart failure. Circulation 1999; 99: 2958–2963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Scherlag BJ, Po S. The intrinsic cardiac nervous system and atrial fibrillation. Curr Opin Cardiol 2006; 21: 51–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. He B, Lu Z, He W, Huang B, Yu L, Wu L, Cui B, Hu X, Jiang H. The effects of atrial ganglionated plexi stimulation on ventricular electrophysiology in a normal canine heart. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2013; 37: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Dollé JP, Rezvan A, Allen FD, Lazarovici P, Lelkes PI. Nerve growth factor‐induced migration of endothelial cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2005; 315: 1220–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Cantarella G, Lempereur L, Presta M, Ribatti D, Lombardo G, Lazarovici P, Zappalà G, Pafumi C, Bernardini R. Nerve growth factor‐endothelial cell interaction leads to angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. FASEB J 2002; 16: 1307–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lazarovici P, Marcinkiewicz C, Lelkes PI. Cross talk between the cardiovascular and nervous systems: neurotrophic effects of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and angiogenic effects of nerve growth factor (NGF)‐implications in drug development. Curr Pharm Des 2006; 12: 2609–2622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Strande JL, Routhu KV, Lecht S, Lazarovici P. Nerve growth factor reduces myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in rat hearts. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol 2013; 24: 81–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Raychaudhuri SK, Raychaudhuri SP, Weltman H, Farber EM. Effect of nerve growth factor on endothelial cell biology: proliferation and adherence molecule expression on human dermal microvascular endothelial cells. Arch Dermatol Res 2001; 293: 291–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hansen‐Algenstaedt N, Algenstaedt P, Schaefer C, Hamann A, Wolfram L, Cingöz G, Kilic N, Schwarzloh B, Schroeder M, Joscheck C, Wiesner L, Rüther W, Ergün S. Neural driven angiogenesis by overexpression of nerve growth factor. Histochem Cell Biol 2006; 125: 637–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Donovan MJ, Miranda RC, Kraemer R, McCaffrey TA, Tessarollo L, Mahadeo D, Sharif S, Kaplan DR, Tsoulfas P, Parada L, Toran‐Allerand CD. Neurotrophin and neurotrophin receptors in vascular smooth muscle cells. Regulation of expression in response to injury. Am J Pathol 1995; 147: 309–324. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kermani P, Rafii D, Jin DK, Whitlock P, Schaffer W, Chiang A, Vincent L, Friedrich M, Shido K, Hackett NR, Crystal RG, Rafii S, Hempstead BL. Neurotrophins promote revascularization by local recruitment of TrkB+ endothelial cells and systemic mobilization of hematopoietic progenitors. J Clin Invest 2005; 115: 653–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Meloni M, Caporali A, Graiani G, Lagrasta C, Katare R, Van Linthout S, Spillmann F, Campesi I, Madeddu P, Quaini F, Emanueli C. Nerve growth factor promotes cardiac repair following myocardial infarction. Circ Res 2010; 106: 1275–1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Yue W, Guo Z. Blockade of spinal nerves inhibits expression of neural growth factor in the myocardium at an early stage of acute myocardial infarction in rats. Br J Anaesth 2012; 109: 345–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Hiltunen JO, Arumäe U, Moshnyakov M, Saarma M. Expression of mRNAs for neurotrophins and their receptors in developing rat heart. Circ Res 1996; 79: 930–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Lam NT, Currie PD, Lieschke GJ, Rosenthal NA, Kaye DM. Nerve growth factor stimulates cardiac regeneration via cardiomyocyte proliferation in experimental heart failure. PLoS ONE 2012; 7: e53210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Oliveira NK, Ferreira RN, Lopes SDN, Chiari E, Camargos E, Martinelli PM. Cardiac autonomic denervation and expression of neurotrophins (NGF and BDNF) and their receptors during experimental Chagas disease. Growth Factors 2017; 35: 161–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Hasan W, Jama A, Donohue T, Wernli G, Onyszchuk G, Al‐Hafez B, Bilgen M, Smith PG. Sympathetic hyperinnervation and inflammatory cell NGF synthesis following myocardial infarction in rats. Brain Res 2006; 1124: 142–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Hasan W, Smith PG. Modulation of rat parasympathetic cardiac ganglion phenotype and NGF synthesis by adrenergic nerves. Auton Neurosci 2009; 145: 17–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Schäper C, Gläser S, Groneberg DA, Kunkel G, Ewert R, Noga O. Nerve growth factor synthesis in human vascular smooth muscle cells and its regulation by dexamethasone. Regul Pept 2009; 157: 3–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Furukawa Y, Furukawa S, Satoyoshi E, Hayashi K. Catecholamines induce an increase in nerve growth factor content in the medium of mouse L‐M cells. J Biol Chem 1986; 261: 6039–6047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Hasan W. Autonomic cardiac innervation: development and adult plasticity. Organogenesis 2013; 9: 176–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Korsching S. The neurotrophic factor concept: a reexamination. J Neurosci 1993; 13: 2739–2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Heumann R, Korsching S, Scott J, Thoenen H. Relationship between levels of nerve growth factor (NGF) and its messenger RNA in sympathetic ganglia and peripheral target tissues. EMBO J 1984; 3: 3183–3189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Luther JA, Birren SJ. Neurotrophins and target interactions in the development and regulation of sympathetic neuron electrical and synaptic properties. Auton Neurosci 2009; 151: 46–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Otten U, Schwab M, Gagnon C, Thoenen H. Selective induction of tyrosine hydroxylase and dopamine beta‐hydroxylase by nerve growth factor: comparison between adrenal medulla and sympathetic ganglia of adult and newborn rats. Brain Res 1977; 133: 291–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Hazari MS, Pan JH, Myers AC. Nerve growth factor acutely potentiates synaptic transmission in vitro and induces dendritic growth in vivo on adult neurons in airway parasympathetic ganglia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2007; 292: L992–L1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Hasan W, Smith PG. Decreased adrenoceptor stimulation in heart failure rats reduces NGF expression by cardiac parasympathetic neurons. Auton Neurosci 2014; 181: 13–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Bennett DL, Dmietrieva N, Priestley JV, Clary D, McMahon SB. trkA, CGRP and IB4 expression in retrogradely labelled cutaneous and visceral primary sensory neurones in the rat. Neurosci Lett 1996; 206: 33–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Ieda M, Fukuda K. Cardiac innervation and sudden cardiac death. Curr Cardiol Rev 2009; 5: 289–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Verge VM, Richardson PM, Wiesenfeld‐Hallin Z, Hökfelt T. Differential influence of nerve growth factor on neuropeptide expression in vivo: a novel role in peptide suppression in adult sensory neurons. J Neurosci 1995; 15: 2081–2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Hua F, Harrison T, Qin C, Reifsteck A, Ricketts B, Carnel C, Williams CA. c‐Fos expression in rat brain stem and spinal cord in response to activation of cardiac ischemia‐sensitive afferent neurons and electrostimulatory modulation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2004; 287: H2728–H2738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Faerman I, Faccio E, Milei J, Nuñez R, Jadzinsky M, Fox D, Rapaport M. Autonomic neuropathy and painless myocardial infarction in diabetic patients. Histologic evidence of their relationship. Diabetes 1977; 26: 1147–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Hu H, Xuan Y, Wang Y, Xue M, Suo F, Li X, Cheng W, Yin J, Liu J, Yan S. Targeted NGF siRNA delivery attenuates sympathetic nerve sprouting and deteriorates cardiac dysfunction in rats with myocardial infarction. PLoS ONE 2014; 9: e95106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Turrini P, Gaetano C, Antonelli A, Capogrossi MC, Aloe L. Nerve growth factor induces angiogenic activity in a mouse model of hindlimb ischemia. Neurosci Lett 2002; 323: 109–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Diao YP, Cui FK, Yan S, Chen ZG, Lian LS, Guo LL, Li YJ. Nerve growth factor promotes angiogenesis and skeletal muscle fiber remodeling in a murine model of hindlimb ischemia. Chin Med J (Engl) 2016; 129: 313–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Ly KH, Régent A, Molina E, Saada S, Sindou P, Le‐Jeunne C, Brézin A, Witko‐Sarsat V, Labrousse F, Robert PY, Bertin P, Bourges JL, Fauchais AL, Vidal E, Mouthon L, Jauberteau MO. Neurotrophins are expressed in giant cell arteritis lesions and may contribute to vascular remodeling. Arthritis Res Ther 2014; 16: 487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Siao CJ, Lorentz CU, Kermani P, Marinic T, Carter J, McGrath K, Padow VA, Mark W, Falcone DJ, Cohen‐Gould L, Parrish DC, Habecker BA, Nykjaer A, Ellenson LH, Tessarollo L, Hempstead BL. ProNGF, a cytokine induced after myocardial infarction in humans, targets pericytes to promote microvascular damage and activation. J Exp Med 2012; 209: 2291–2305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Kraemer R. Reduced apoptosis and increased lesion development in the flow‐restricted carotid artery of p75(NTR)‐null mutant mice. Circ Res 2002; 91: 494–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Zhou S, Chen LS, Miyauchi Y, Miyauchi M, Kar S, Kangavari S, Fishbein MC, Sharifi B, Chen PS. Mechanisms of cardiac nerve sprouting after myocardial infarction in dogs. Circ Res 2004; 95: 76–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Abe T, Morgan DA, Gutterman DD. Protective role of nerve growth factor against postischemic dysfunction of sympathetic coronary innervation. Circulation 1997; 95: 213–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Lee TM, Chang NC, Lin SZ. Inhibition of infarction‐induced sympathetic innervation with endothelin receptor antagonism via a PI3K/GSK‐3β‐dependent pathway. Lab Invest 2017; 97: 243–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Cao JM, Chen LS, KenKnight BH, Ohara T, Lee MH, Tsai J, Lai WW, Karagueuzian HS, Wolf PL, Fishbein MC, Chen PS. Nerve sprouting and sudden cardiac death. Circ Res 2000; 86: 816–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Qin F, Vulapalli RS, Stevens SY, Liang CS. Loss of cardiac sympathetic neurotransmitters in heart failure and NE infusion is associated with reduced NGF. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2002; 282: H363–H371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Kimura K, Kanazawa H, Ieda M, Kawaguchi‐Manabe H, Miyake Y, Yagi T, Arai T, Sano M, Fukuda K. Norepinephrine‐induced nerve growth factor depletion causes cardiac sympathetic denervation in severe heart failure. Auton Neurosci 2010; 156: 27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Park JH, Hong SY, Wi J, Lee DL, Joung B, Lee MH, Pak HN. Catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation raises the plasma level of NGF‐β which is associated with sympathetic nerve activity. Yonsei Med J 2015; 56: 1530–1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Wang ZG, Li H, Huang Y, Li R, Wang XF, Yu LX, Guang XQ, Li L, Zhang HY, Zhao YZ, Zhang C, Li XK, Wu RZ, Chu MP, Xiao J. Nerve growth factor‐induced Akt/mTOR activation protects the ischemic heart via restoring autophagic flux and attenuating ubiquitinated protein accumulation. Oncotarget 2017; 8: 5400–5413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Kalogeris T, Baines CP, Krenz M, Korthuis RJ. Cell biology of ischemia/reperfusion injury. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 2012; 298: 229–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Buja LM, Entman ML. Modes of myocardial cell injury and cell death in ischemic heart disease. Circulation 1998; 98: 1355–1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Maxwell SR, Lip GY. Reperfusion injury: a review of the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations and therapeutic options. Int J Cardiol 1997; 58: 95–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Zhang RL, Guo Z, Wang LL, Wu J. Degeneration of capsaicin sensitive sensory nerves enhances myocardial injury in acute myocardial infarction in rats. Int J Cardiol 2012; 160: 41–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Mattson MP, Lovell MA, Furukawa K, Markesbery WR. Neurotrophic factors attenuate glutamate‐induced accumulation of peroxides, elevation of intracellular Ca2+ concentration, and neurotoxicity and increase antioxidant enzyme activities in hippocampal neurons. J Neurochem 1995; 65: 1740–1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Xu B, Xu H, Cao H, Liu X, Qin C, Zhao Y, Han X, Li H. Intermedin improves cardiac function and sympathetic neural remodeling in a rat model of post myocardial infarction heart failure. Mol Med Rep 2017; 16: 1723–1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Lee TM, Chen WT, Yang CC, Lin SZ, Chang NC. Sitagliptin attenuates sympathetic innervation via modulating reactive oxygen species and interstitial adenosine in infarcted rat hearts. J Cell Mol Med 2015; 19: 418–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Lee TM, Lin SZ, Chang NC. Antiarrhythmic effect of lithium in rats after myocardial infarction by activation of Nrf2/HO‐1 signaling. Free Radic Biol Med 2014; 77: 71–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Pattison JS, Robbins J. Autophagy and proteotoxicity in cardiomyocytes. Autophagy 2011; 7: 1259–1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Gussak G, Pfenniger A, Wren L, Gilani M, Zhang W, Yoo S, Johnson DA, Burrell A, Benefield B, Knight G, Knight BP, Passman R, Goldberger JJ, Aistrup G, Wasserstrom JA, Shiferaw Y, Arora R. Region‐specific parasympathetic nerve remodeling in the left atrium contributes to creation of a vulnerable substrate for atrial fibrillation. JCI Insight 2019; 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Nguyen BL, Li H, Fishbein MC, Lin SF, Gaudio C, Chen PS, Chen LS. Acute myocardial infarction induces bilateral stellate ganglia neural remodeling in rabbits. Cardiovasc Pathol 2012; 21: 143–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Chen PS, Chen LS, Fishbein MC, Lin SF, Nattel S. Role of the autonomic nervous system in atrial fibrillation: pathophysiology and therapy. Circ Res 2014; 114: 1500–1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Li Z, Wang M, Zhang Y, Zheng S, Wang X, Hou Y. The effect of the left stellate ganglion on sympathetic neural remodeling of the left atrium in rats following myocardial infarction. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2015; 38: 107–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Korsching S, Thoenen H. Nerve growth factor in sympathetic ganglia and corresponding target organs of the rat: correlation with density of sympathetic innervation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1983; 80: 3513–3516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Zhou S, Jung BC, Tan AY, Trang VQ, Gholmieh G, Han SW, Lin SF, Fishbein MC, Chen PS, Chen LS. Spontaneous stellate ganglion nerve activity and ventricular arrhythmia in a canine model of sudden death. Heart Rhythm 2008; 5: 131–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Wang S, Zhou X, Huang B, Wang Z, Liao K, Saren G, Lu Z, Chen M, Yu L, Jiang H. Spinal cord stimulation protects against ventricular arrhythmias by suppressing left stellate ganglion neural activity in an acute myocardial infarction canine model. Heart Rhythm 2015; 12: 1628–1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Wang Z, Li S, Lai H, Zhou L, Meng G, Wang M, Lai Y, Chen H, Zhou X, Jiang H. Interaction between endothelin‐1 and left stellate ganglion activation: a potential mechanism of malignant ventricular arrhythmia during myocardial ischemia. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2019; 2019: 6508328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Wang S, Wu L, Zhai Y, Li X, Li B, Zhao D, Jiang H. Noninvasive light emitting diode therapy: a novel approach for postinfarction ventricular arrhythmias and neuroimmune modulation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2019; 30: 1138–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Cao JM, Fishbein MC, Han JB, Lai WW, Lai AC, Wu TJ, Czer L, Wolf PL, Denton TA, Shintaku IP, Chen PS, Chen LS. Relationship between regional cardiac hyperinnervation and ventricular arrhythmia. Circulation 2000; 101: 1960–1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Verrier RL, Kwaku KF. Frayed nerves in myocardial infarction: the importance of rewiring. Circ Res United States 2004; 95: 5–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Xi Y, Cheng J. Dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system in atrial fibrillation. J Thorac Dis 2015; 7: 193–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Shimano M, Shibata R, Inden Y, Yoshida N, Uchikawa T, Tsuji Y, Murohara T. Reactive oxidative metabolites are associated with atrial conduction disturbance in patients with atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm 2009; 6: 935–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Kiriazis H, Du XJ, Feng X, Hotchkin E, Marshall T, Finch S, Gao XM, Lambert G, Choate JK, Kaye DM. Preserved left ventricular structure and function in mice with cardiac sympathetic hyperinnervation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2005; 289: H1359–H1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Chang CM, Wu TJ, Zhou S, Doshi RN, Lee MH, Ohara T, Fishbein MC, Karagueuzian HS, Chen PS, Chen LS. Nerve sprouting and sympathetic hyperinnervation in a canine model of atrial fibrillation produced by prolonged right atrial pacing. Circulation 2001; 103: 22–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Hirose M, Leatmanoratn Z, Laurita KR, Carlson MD. Partial vagal denervation increases vulnerability to vagally induced atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2002; 13: 1272–1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Choi EK, Shen MJ, Han S, Kim D, Hwang S, Sayfo S, Piccirillo G, Frick K, Fishbein MC, Hwang C, Lin SF, Chen PS. Intrinsic cardiac nerve activity and paroxysmal atrial tachyarrhythmia in ambulatory dogs. Circulation 2010; 121: 2615–2623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Bettoni M, Zimmermann M. Autonomic tone variations before the onset of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Circulation 2002; 105: 2753–2759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Piccini JP, Fauchier L. Rhythm control in atrial fibrillation. Lancet 2016; 388: 829–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Kangavari S, Oh YS, Zhou S, Youn HJ, Lee MY, Jung WS, Rho TH, Hong SJ, Kar S, Kerwin WF, Swerdlow CD, Gang ES, Gallik DM, Goodman JS, Chen YD, Chen PS. Radiofrequency catheter ablation and nerve growth factor concentration in humans. Heart Rhythm 2006; 3: 1150–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]