Abstract

Background

Adults with congenital heart disease (CHD) have been considered potentially high risk for novel coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) mortality or other complications.

Objectives

This study sought to define the impact of COVID-19 in adults with CHD and to identify risk factors associated with adverse outcomes.

Methods

Adults (age 18 years or older) with CHD and with confirmed or clinically suspected COVID-19 were included from CHD centers worldwide. Data collection included anatomic diagnosis and subsequent interventions, comorbidities, medications, echocardiographic findings, presenting symptoms, course of illness, and outcomes. Predictors of death or severe infection were determined.

Results

From 58 adult CHD centers, the study included 1,044 infected patients (age: 35.1 ± 13.0 years; range 18 to 86 years; 51% women), 87% of whom had laboratory-confirmed coronavirus infection. The cohort included 118 (11%) patients with single ventricle and/or Fontan physiology, 87 (8%) patients with cyanosis, and 73 (7%) patients with pulmonary hypertension. There were 24 COVID-related deaths (case/fatality: 2.3%; 95% confidence interval: 1.4% to 3.2%). Factors associated with death included male sex, diabetes, cyanosis, pulmonary hypertension, renal insufficiency, and previous hospital admission for heart failure. Worse physiological stage was associated with mortality (p = 0.001), whereas anatomic complexity or defect group were not.

Conclusions

COVID-19 mortality in adults with CHD is commensurate with the general population. The most vulnerable patients are those with worse physiological stage, such as cyanosis and pulmonary hypertension, whereas anatomic complexity does not appear to predict infection severity.

Key Words: adult congenital heart disease, coronavirus, COVID-19, hospitalization

Abbreviations and Acronyms: CHD, congenital heart disease; CI, confidence interval; COVID-19, coronavirus disease-2019; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ICU, intensive care unit; OR, odds ratio; PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension; PCR, polymerase chain reaction

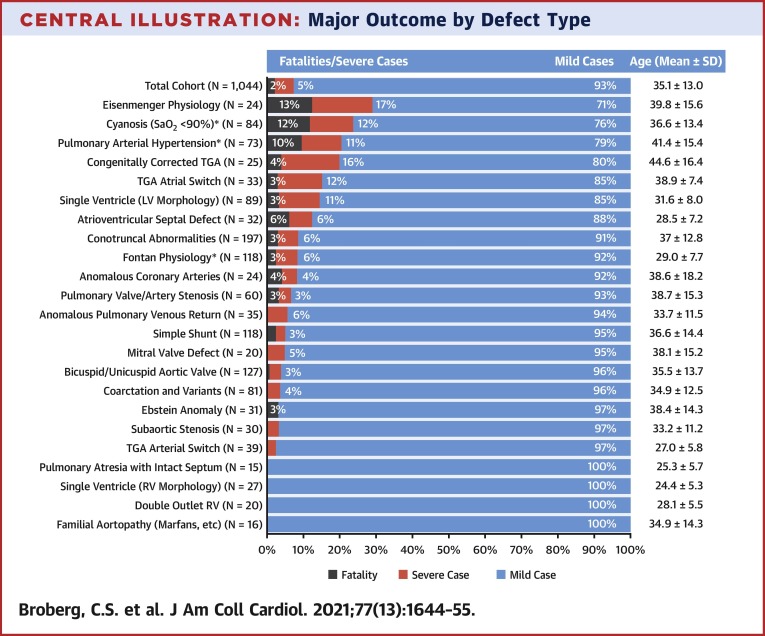

Central Illustration

Early data on the coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic identified heart disease as a risk factor for mortality (1,2), but there is also uncertainty about what conditions merit inclusion under this general term (3). Adults with congenital heart disease (CHD), numbering >1.5 million in the United States (4,5), are recognized as a population with significant morbidity (6) and as vulnerable to many types of cardiovascular deterioration and dysfunction. As such, they have largely been considered high risk and often adopt a highly restrictive lifestyle and employment choices accordingly. Early publications in CHD reported different risks (7,8) but suggested worse risk in higher physiological stages (9).

In the absence of data, consensus recommendations for COVID-19 and CHD have been made based on sensible suppositions regarding at-risk subtypes, including a proposed risk stratification for COVID-19 complications (10). Another group outlined the potential viral impact of CHD (11). Others have based recommendations on anatomic and/or physiological stage (12).

To more accurately inform risk stratification and provide guidance for individual patients with CHD and their providers, we established this large international study. Our overarching objectives were to determine which adults with CHD are most vulnerable to the adverse consequences of COVID-19 and to quantify the magnitude of those consequences. Specifically, we aimed to determine risk factors associated with death (primary outcome) or severe infection, meaning need for intensive care unit (ICU) admission, endotracheal intubation, acute respiratory distress syndrome, or renal replacement therapy (secondary outcome).

Methods

Study design

This was an international, multicenter, retrospective cohort study. Collaborators from adult CHD centers globally were recruited via the Adult Congenital Heart Association, the International Society for Adult Congenital Heart Disease, the Alliance for Adult Research in Congenital Cardiology, the Canadian Adult Congenital Heart Network, and by word of mouth to colleagues worldwide. Study administration and coordination was done by the University of California, Los Angeles, whereas Oregon Health and Science University served as the data coordinating center. The overall study was approved by both host institutions, and each participating center obtained local ethics approval.

Eligibility criteria

Eligible patients met the following inclusion criteria for enrollment: known diagnosis of CHD, age 18 years or older, and either positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for the novel coronavirus or positive antibody test following a clinical illness. Patients with a presumptive diagnosis of COVID-19 based upon clinical symptoms and circumstances were also included, because testing availability and sensitivity were known to vary by location and assay and over time. Patients with a known familial aortopathy were included as were those with syndromes if a congenital heart defect was present. We excluded patients with patent foramen ovale, mitral valve prolapse, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, ventricular noncompaction, congenital arrhythmia, or those who had undergone heart transplantation.

Data collection

For each patient, comprehensive clinical data were abstracted from existing medical records by collaborating investigators at each center. Data included anatomic diagnoses, subsequent interventions, general anatomic classification, and physiological stage based on the 2018 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association joint guidelines on adult CHD (9), a history of major cardiac and noncardiac comorbidities, medications at most recent outpatient visit, and most recent laboratory and echocardiographic findings obtained before but within 12 months of infection. Echo findings included semi-quantitative valve assessment (mild to moderate to severe). PCR testing results, clinical presentation, and laboratory and imaging results during infection and course of illness were also recorded, including details of any hospitalization. Race and ethnicity were requested for patients from collaborating centers within the United States.

Data were entered online using the Research Electronic Data Capture data management system, which enables multiuser data collection. Patients were given study-specific identifiers. No protected patient identifiers, including dates, were collected.

Quality control was performed by the data coordinating center. Data were reviewed for internal consistency. For example, designation of cyanosis was confirmed by a reported resting oxygen saturation of <90%, and patients with Fontan physiology were ensured to have an anatomic defect consistent with single ventricle palliation. All inconsistencies and outliers were flagged, and queries were sent to local investigators for confirmation or correction.

We used a hierarchical classification to categorize patients by their single most complex defect type (13), such that each patient was included in only 1 defect category. Patients identified as having Eisenmenger physiology, with both cyanosis and pulmonary hypertension in the setting of a shunt, were designated as such, and removed from their respective anatomic defect category. Patients with a systemic right ventricle included those with transposed great arteries and an atrial switch operation, or congenitally corrected transposition (biventricular repairs only). Contributing site investigators were asked to designate anatomic severity (simple, moderate, or complex) based on the guideline classification scheme (9), and designations were reviewed for consistency with the given congenital defect. Discrepancies were clarified or corrected with site investigators as needed. Similarly, physiological stage designation was compared with other collected data, such as New York Heart Association functional class, arrhythmia history, end-organ dysfunction, valve disease, and so on. Discrepancies were flagged for review by local investigators. In some instances when physiological stage was not provided by local investigators, who might not have been familiar with the classification scheme, physiological stage was imputed based on other provided data with agreement of 2 investigators blinded to outcomes.

Statistical analyses

From available data, body surface area, body mass index, and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR; based on the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation) were calculated. Severe viral infections were defined as those that required ICU admission, endotracheal intubation for mechanical ventilation, acute respiratory distress syndrome, renal replacement therapy, need for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or death. Other cases were considered mild, including hospitalizations that did not include 1 of the aforementioned criteria, because some patients had other indications for admission. Patients with either moderate or severe valve regurgitation or stenosis of any valve, by recent echocardiography as reported by local investigators, were identified as having moderate to severe valve dysfunction.

Data analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25 (IBM Corp, Armonk, New York). Overall rates of the primary outcome (death) and the secondary outcome (severe infection) were quantified with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Similar rates were determined by decade of age, CHD defect group, and by anatomic and/or physiological classification scheme. Groups with or without primary and secondary outcomes were compared using the chi-square test, Fisher exact test, Student’s t-test, or Mann-Whitney U test, as appropriate. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs were determined using binary logistic regression to report the strength of association between risk factor exposure and mortality. Because of limited mortality events, multivariable regression was limited to specific comparisons with no more than 2 independent predictors, and categorical variables were collapsed to dichotomous variables to avoid empty cells. Analysis including only PCR-positive patients was repeated to explore whether the method of diagnosis affected results. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. Because of the exploratory nature of this study, no corrections were made for multiple tests.

Results

Study cohort

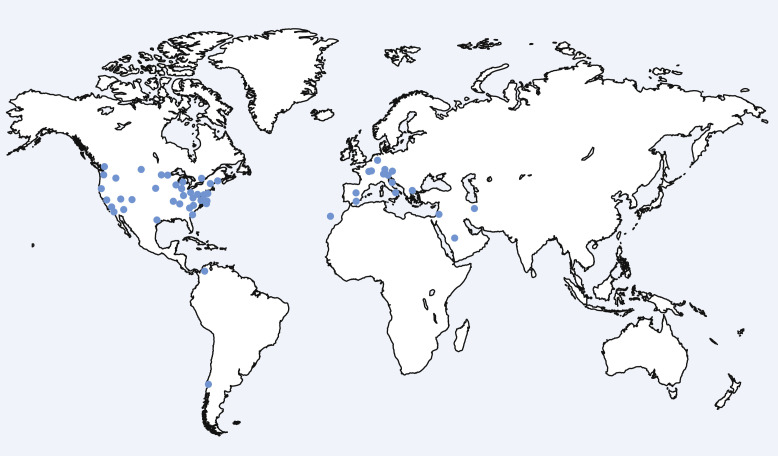

A total of 58 CHD centers contributed to the study (Figure 1 ). Of 1,115 submitted patients, 1,044 met full inclusion and/or exclusion criteria. Mean age was 35.1 ± 13.0 years (range 18 to 86 years), and 51% were women. Most patients (n = 907; 87%) had a positive PCR test or positive antibodies detected after a clinical illness. The remainder (n = 137) were diagnosed based on clinical presentation alone. Most patients (n = 787; 75%) were followed by U.S. centers, with race reported in 784 and ethnicity in 739.

Figure 1.

Global Distribution of Contributing Centers

Points identify the location of the 58 congenital heart centers participating in the study.

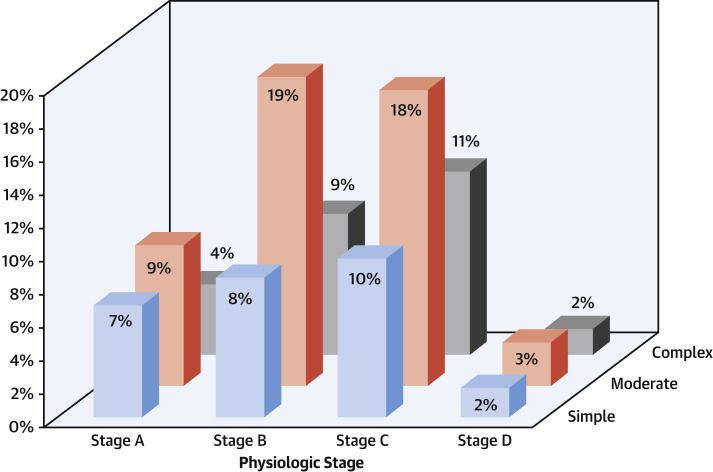

The cohort included a broad representation of the spectrum of CHD complexity and comorbidity. The anatomic and/or physiological classification for the cohort is shown in Figure 2 . Previous atrial arrhythmia occurred in 259 (25.9%) patients, and previous ventricular arrhythmia in 103 (9.7%) patients. There were 132 (12.6%) patients with implanted pacemakers or defibrillators, 161 (15.4%) patients with hypertension, 88 (8.4%) with known genetic syndromes, 65 (6.2%) with diabetes, and 19 (1.8%) patients with cirrhosis. In addition, 23 women were pregnant at the time of infection.

Figure 2.

Distribution of the Study Cohort Anatomic and/or Physiological Categorization

Column heights indicate the percentage of each anatomic and/or physiologic subtype from the total cohort. Classification is based on the scheme as outlined in the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association 2018 guidelines for adult congenital heart disease (9).

Fever, dry cough, and malaise were the most common presenting symptoms, occurring in approximately one-half of the cohort (Table 1 ). There were 60 (6%) patients who had no presenting symptoms but were tested based upon a known incidental exposure or need for clearance before a procedure. Of the total cohort, 179 patients (17%) required hospitalization, which included those who tested positive during admission for other indications. Serum troponin was reported in 30 patients, all but 1 of whom were hospitalized and was elevated in 22 patients.

Table 1.

Presenting Symptoms of COVID-19 Infection

| Fever | 458 (44) |

| Dry cough | 405 (39) |

| Malaise/fatigue | 403 (39) |

| Myalgia | 282 (27) |

| Dyspnea | 235 (23) |

| Loss of smell | 236 (23) |

| Headache | 149 (14) |

| Chest pain | 130 (12) |

| Diarrhea | 108 (10) |

| Congestion | 107 (10) |

| Productive cough | 65 (6) |

| None∗ | 60 (6) |

| Loss of taste | 66 (6) |

| Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting | 57 (5) |

| Chills | 39 (4) |

| Other/miscellaneous | 48 (5) |

Values are n (%).

Asymptomatic subjects tested before an elective procedure or in response to a suspected exposure to the novel coronavirus.

Primary outcome: fatalities

Death occurred in 28 subjects, of whom 4 were deemed unrelated to acute COVID-19 infection. One patient died from metastatic cancer, 1 from bacterial pneumonia, and 1 from cardiac arrest at home without previous positive COVID-19 testing. One additional death occurred in a patient with a systemic right ventricle who, 4 months after COVID-19 hospitalization, presented with ventricular arrhythmia and cardiogenic shock. The remaining 24 deaths (mean age: 40.8 ± 17.6 years; range 18 to 85 years; 75% male) were all adjudicated as COVID-19 related, resulting in a 2.3% COVID-19 related case/fatality rate (95% CI: 1.4% to 3.2%). All were PCR positive, except 1 young adult with an uncorrected atrioventricular septal defect and Eisenmenger syndrome who presented with fever, cough, anosmia, myalgia, and an elevated leukocyte count, and who died of hemoptysis. Treating providers deemed the clinical picture consistent with COVID-19, although testing could not be performed. When analysis was restricted to the 907 patients with positive PCR or antibodies, the COVID-19 case/fatality ratio was 2.5% (95% CI: 1.5% to 3.6%).

All COVID-19 deaths occurred in hospitalized subjects. Median hospital duration before death was 9 days (range 1 to 74 days). Of these, 19 patients were intubated, 10 had a significantly elevated troponin consistent with myocardial damage, 9 required renal replacement therapy, and 3 were placed on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. One patient had been living in a nursing home before infection and had previously decided against resuscitation. In terms of CHD diagnoses, 10 patients were cyanotic, 5 of whom had Eisenmenger syndrome. Two additional patients had pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) without cyanosis. Three patients who died had Fontan physiology. One had asplenia, poor systolic function, and protein-losing enteropathy and presented in respiratory distress; the second had ‘failing Fontan’ physiology with multiple admissions prior to infection; the third had resting cyanosis, prior atrial and ventricular arrhythmia, and mitral valve dysfunction. Two patients had a systemic RV in the setting of transposition of the great arteries, both of whom had had multiple prior admissions for congestive heart failure. There were 7 deaths in patients with diabetes, all obese, age 42 to 85 years, and all with simple defects.

Risk factors for death

Factors associated with death (Table 2 ) included male sex, higher body mass index, previous atrial arrhythmia, diabetes, previous heart failure admission, cyanosis, lower resting oxygen saturation, PAH, increased subpulmonic ventricular systolic pressure as estimated by the most recent echocardiogram, and eGFR <60 ml/min/m2 before infection. Age was skewed towards younger subjects (Figure 3 ) and was not significantly associated with death despite a higher proportion of deaths in older groups. Factors not associated with death were systemic ventricular systolic function (either by reported ejection fraction or semi-quantitative designation), Fontan palliation, systemic hypertension, at least moderate valve dysfunction, smoking and/or vaping history, use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, beta-blockers before infection, previous arrhythmias, presence of a pacemaker and/or defibrillator, or race/ethnicity. Troponin elevation was also not associated with death, because 3 of 6 patients with a normal troponin died, and 9 of 17 patients with a troponin >50 ng/ml survived. ORs for significant univariate predictors of COVID-19−related death are shown in Table 3 . Previous heart failure admission, cyanosis, diabetes, and physiological stage were all strongly predictive.

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics

| Survived | Died | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, yrs | 32 ± 17 | 39 ± 31 | 0.16 |

| Male | 486/1,015 (48) | 20/24 (83) | 0.001 |

| Weight, kg | 77.5 ± 21.4 | 91.0 ± 35.1 | 0.075 |

| Height, cm | 168 ± 11 | 164 ± 12 | 0.23 |

| Body mass index | 27.1 ± 6.6 | 32.3 ± 10.4 | 0.016 |

| Black∗ | 66/771 (8.6) | 2/13 (15.4) | 0.39 |

| Hispanic∗ | 99/726 (14) | 3/13 (23) | 0.33 |

| Smoking/vaping | 80/1,020 (7.8) | 1/24 (4.2) | 0.51 |

| Medications | |||

| ACE/ARB use | 274/1,005 (27) | 9/24 (38) | 0.27 |

| Beta-blocker use | 348/1,007 (34) | 12/24 (50) | 0.65 |

| Medical/cardiac history | |||

| Previous atrial arrhythmia | 248/1,002 (25) | 11/24 (46) | 0.019 |

| Pacemaker or implanted defibrillator | 103/1,009 (12.9) | 2/24 (8.3) | 0.66 |

| Hypertension | 156/1,003 (16) | 5/24 (21) | 0.48 |

| Diabetes | 58/1,014 (5.7) | 7/24 (29.2) | <0.001 |

| Known coronary artery disease | 22/1,004 (2.2) | 2/24 (8.3) | 0.049 |

| Previous heart failure admission | 88/1,001 (8.8) | 10/24 (42) | <0.001 |

| Ejection fraction <40% | 34/654 (5.2) | 1/19 (5.3) | 0.99 |

| Systemic ventricular ejection fraction by echo | 57 ± 10 | 54 ± 9 | 0.19 |

| Systemic right ventricle (biventricular) | 59/1,020 (5.8) | 2/4 (50) | 0.60 |

| Moderate-severe valve dysfunction | 333/807 (41) | 13/20 (65) | 0.058 |

| Fontan palliation | 115/1,017 (11.3) | 3/24 (12.5) | 0.86 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 66/1,008 (6.5) | 7/24 (29) | <0.001 |

| Sub-pulmonic ventricular systolic pressure by echo, mm Hg | 39 ± 22 | 54 ± 30 | 0.006 |

| Previous resting oxygen saturation, % | 96 ± 4 | 92 ± 5 | <0.001 |

| Cyanosis (oxygen saturation <90%) | 74/998 (7.7) | 10/24 (42) | <0.001 |

| Supplemental oxygen use | 28/1,002 (2.8) | 4/24 (17) | <0.001 |

| Laboratory findings | |||

| Hemoglobin | 14.2 ± 3.1 | 15.5 ± 3.4 | 0.09 |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 0.87 ± 0.35 | 1.29 ± 1.19 | 0.086 |

| eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2† | 38/1,015 (3.7) | 4/24 (17) | 0.001 |

| Albumin, mg/dl | 4.3 ± 0.6 | 4.0 ± 0.7 | 0.042 |

Values are mean ± SD or n/N (%).

ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB = angiotensin receptor blocker medication.

Data on race and ethnicity were requested from U.S. centers.

Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) is based on the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation.

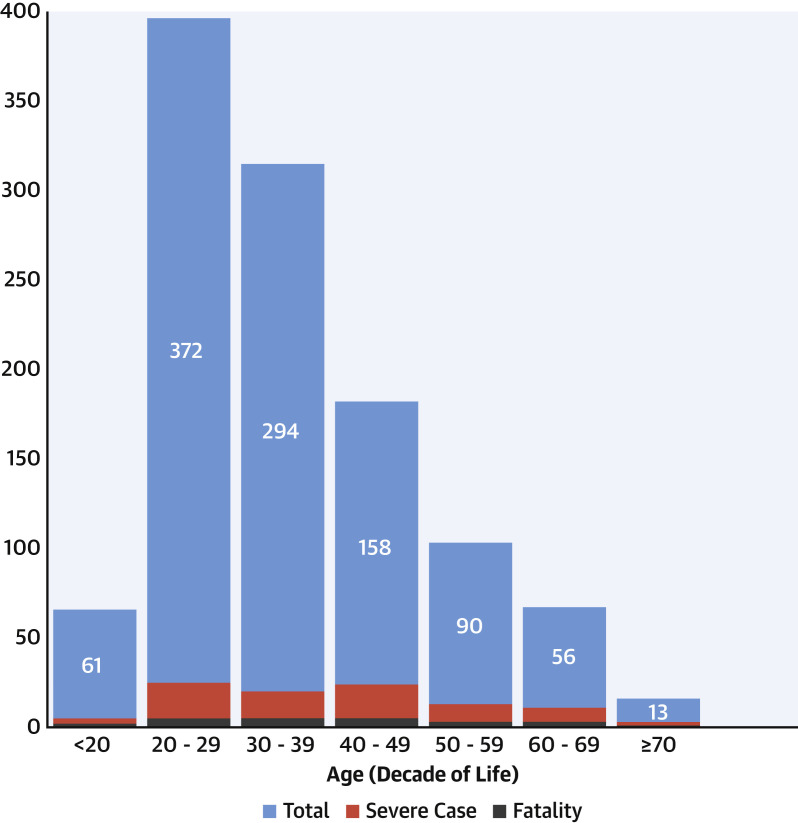

Figure 3.

Histogram by Age and Major Outcome

Columns show the study population by decade of age, with severe cases (red) and deaths (gray) indicated within each.

Table 3.

ORs for Variables Associated With Case/Fatality

| OR | 95% CI | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyanosis (oxygen saturation <90%) | 8.9 | 3.8−20.8 | <0.001 |

| Previous heart failure admission | 7.4 | 3.2–17.2 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 6.8 | 2.7–17.0 | <0.001 |

| Physiological stage C or D | 6.4 | 2.2–19.0 | 0.001 |

| Supplemental oxygen use | 7.0 | 2.2–21.7 | 0.001 |

| Pulmonary arterial hypertension | 5.9 | 2.4–14.7 | <0.001 |

| Male | 5.4 | 1.8−16.0 | 0.002 |

| eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 | 5.1 | 1.7−15.8 | 0.004 |

| Body mass index | 1.08 | 1.04−1.13 | 0.001 |

| Age (per yr) | 1.03 | 1.002−1.06 | 0.033 |

CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio; other abbreviation as in Table 2.

Death and severe cases were distributed across the age spectrum (Figure 3), although as a percentage were proportionately greater in older age decades. Anatomic complexity was not associated with death, but physiological stage was, with a higher proportion of deaths in more severe stages (p = 0.002 by chi-square test). Overall rates of death for stage A (healthiest) through stage D (least healthy) were 0%, 1.1%, 3.9%, and 7.9% respectively. Paradoxically, there were no deaths among the complex anatomy + physiological stage D group (n = 0 of 16); rather, the highest rates of death were among those with simple anatomy + physiological stage D (n = 3 of 19).

To further consider the possible effects of age on anatomic and physiological designations, we divided the entire cohort into age tertiles, specifically 18 to 27 years, 28 to 39 years, and 40 years or older (Table 4 ). Deaths were more common in the oldest tertile (3.8%). In each tertile, deaths were generally more common in physiological stage C or D, regardless of anatomic complexity. To explore the potential for interaction between anatomy and physiology as predictors of death, we performed a multiple binary logistic regression analysis using physiological stages (AB vs. CD) and anatomic complexity (severe vs. simple and/or moderate) as independent variables. Physiological stage CD was predictive (OR: 6.6; 95% CI: 2.2 to 19.4; p = 0.001), whereas complex anatomy was not predictive (OR: 0.7; 95% CI: 0.3 to 1.9; p = 0.47).

Table 4.

Mortality Based on Anatomic Complexity or Physiological Stage (by Age Tertile)

| Stage A | Stage B | Stage C | Stage D | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age 18−27 yrs | |||||

| Simple | 0/27 (0) | 0/29 (0) | 1/32 (3.1) | 1/6 (16.7) | 2/94 (2.1) |

| Moderate | 0/36 (0) | 1/73 (1.4) | 1/38 (2.6) | 1/6 (16.7) | 3/153 (2) |

| Complex | 0/24 (0) | 0/34 (0) | 2/45 (4.4) | 0/6 (0) | 2/109 (1.8) |

| Total | 0/87 (0) | 1/136 (0.7) | 4/115 (3.5) | 2/18 (11.1) | 7/356 (2) |

| Age 28−40 yrs | |||||

| Simple | 0/21 (0) | 0/32 (0) | 0/32 (0) | 0/5 (0) | 0/90 (0) |

| Moderate | 0/26 (0) | 1/57 (1.8) | 2/74 (2.7) | 0/11 (0) | 3/168 (1.8) |

| Complex | 0/17 (0) | 0/33 (0) | 2/48 (4.2) | 0/4 (0) | 2/102 (2) |

| Total | 0/64 (0) | 1/122 (0.8) | 4/154 (2.6) | 0/20 (0) | 5/360 (1.4) |

| Age ≥40 yrs | |||||

| Simple | 0/22 (0) | 0/26 (0) | 2/35 (5.7) | 2/8 (25) | 4/91 (4.4) |

| Moderate | 0/26 (0) | 1/62 (1.6) | 5/71 (7) | 1/11 (9.1) | 7/170 (4.1) |

| Complex | 0/3 (0) | 1/21 (4.8) | 0/21 (0) | 0/6 (0) | 1/51 (2) |

| Total | 0/51 (0) | 2/109 (1.8) | 7/127 (5.5) | 3/25 (12) | 12/312 (3.8) |

| Total cohort | |||||

| Simple | 0/70 (0) | 0/87 (0) | 3/99 (3) | 3/19 (15.8) | 6/275 (2.2) |

| Moderate | 0/88 (0) | 3/192 (1.6) | 8/183 (4.4) | 2/28 (7.1) | 13/491 (2.6) |

| Complex | 0/44 (0) | 1/88 (1.1) | 4/114 (3.5) | 0/16 (0) | 5/262 (1.9) |

| Total | 0/202 (0) | 4/367 (1.1) | 15/396 (3.8) | 5/63 (7.9) | 24/1028 (2.3) |

Values are n/N (%). Columns represent different physiological stages. Anatomic complexity is given by row. Groups with ≥3% fatality rate are indicated in bold.

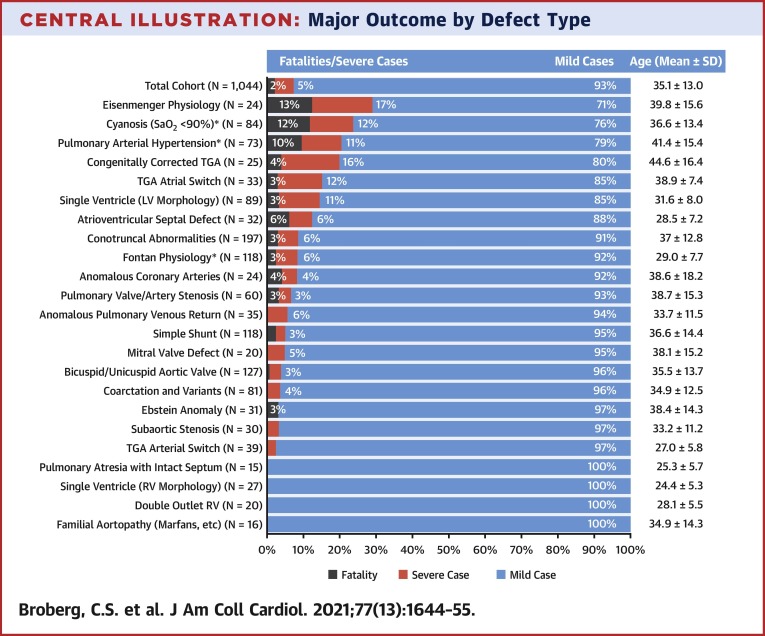

Rates of mortality and/or severe course varied by CHD diagnosis (Central Illustration ). The highest mortality rates were observed in patients with Eisenmenger physiology, patients with cyanosis (with or without PAH), and those with PAH (with or without cyanosis). Of patients with cyanosis but without PAH, there were 5 deaths among 47 (10.6%). Conversely, of 35 patients with PAH but without cyanosis, only 2 died (5.7%). Generally, defect groups with higher mortality tended to have an older mean age (Central Illustration).

Central Illustration.

Major Outcome by Defect Type

Breakdown of the entire cohort by congenital defect category. Those with severe disease exclusive of death (red) and fatal cases (gray) are indicated, with percentage by category. ∗Groups that were not exclusive of others; patients with cyanosis, pulmonary hypertension, or Fontan are pooled regardless of underlying anatomy. All other groups are mutually exclusive. Age distribution is given for each category. Conotruncal abnormalities include tetralogy of Fallot, pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect, and truncus arteriosus. LV = left ventricle; RV= right ventricle; TGA = transposition of the great arteries.

All analyses were repeated using only the cohort of 907 patients who tested positive by PCR or who had confirmed positive antibody testing after a clinical presentation. There were no changes in variable significance; male sex, oxygen saturation, use of supplemental oxygen, cyanosis, PAH, previous heart failure admission, diabetes, physiological stage, creatinine, low eGFR, and estimated sub-pulmonic ventricular systolic pressure remained significant. However, beta-blocker use and lower left ventricular ejection fraction were significantly associated with COVID-19−related death. Other variables were not.

Secondary outcome: severe cases

There were 67 (6.4%) patients who required ICU care, 36 of whom were intubated. Of those intubated, 18 (52%) died. Variables of significance for predicting severe disease course (Table 5 ) were identical to those predictive of death. Beta-blockers and having a systemic right ventricle were also significant. Additional complications from the entire cohort included new arrhythmias in 36 (3.4%) patients and bleeding or coagulopathic events (as judged by contributing providers) in 32 (3.1%) patients. Of the 23 pregnant women, all survived, but 2 were treated in the ICU late in pregnancy.

Table 5.

Factors Compared Based on Mild Versus Severe Cases

| Mild Case | Severe Case∗ | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, yrs | 32 ± 16 | 40 ± 23 | 0.001 |

| Male | 454/963 (47) | 52/76 (68) | <0.001 |

| Weight, kg | 77.5 ± 20.8 | 83.0 ± 33.0 | 0.16 |

| Height, cm | 168 ± 11 | 166 ± 12 | 0.063 |

| Body mass index | 27.2 ± 6.5 | 29.2± 9.9 | 0.091 |

| Smoking/vaping history | 76/967 (7.9) | 5/77 (6.5) | 0.66 |

| Black | 62/739 (8.4) | 6/45 (13.3) | 0.25 |

| Hispanic | 93/695 (14) | 9/44 (21) | 0.19 |

| Medications | |||

| ACE/ARB use | 255/953 (27) | 28/76 (37) | 0.058 |

| Beta-blocker use | 325/956 (34) | 35/75 (46) | 0.027 |

| Medical/cardiac history | |||

| Previous atrial arrhythmia | 233/950 (25) | 26/76 (34) | 0.061 |

| Pacemaker or implantable defibrillator | 119/956 (12) | 13/77 (17) | 0.26 |

| Hypertension | 147/951 (16) | 14/76 (18) | 0.49 |

| Diabetes | 50/961 (5.2) | 15/77 (20) | <0.001 |

| Known coronary artery disease | 20/952 (2.1) | 4/76 (5.3) | 0.079 |

| Previous heart failure admission | 72/951 (7.6) | 26/74 (35) | <0.001 |

| Ejection fraction <40% | 29/617 (4.7) | 6/56 (11) | 0.052 |

| Systemic ventricular ejection fraction by echo | 57 ± 10 | 53 ± 10 | 0.001 |

| Systemic right ventricle (biventricular) | 51/967 (5.3) | 10/77 (13) | 0.005 |

| Moderate-severe valve dysfunction by echo | 316/766 (41) | 30/61 (49) | 0.28 |

| Fontan palliation | 108/964 (11.2) | 10/77 (13) | 0.64 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 58/955 (6.1) | 15/77 (20) | <0.001 |

| Sub-pulmonic ventricular systolic pressure by echo, mm Hg | 38 ± 21 | 52 ± 28 | 0.006 |

| Previous resting oxygen saturation, % | 96 ± 4 | 93 ± 6 | <0.001 |

| Cyanosis (oxygen saturation <90%) | 64/947 (6.8) | 20/75 (27) | <0.001 |

| Supplemental oxygen use | 24/950 (2.5) | 8/76 (10.5) | <0.001 |

| Laboratory findings | |||

| Hemoglobin | 14.21 ± 3.1 | 14.8± 2.8 | 0.105 |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 0.86 ± 0.34 | 1.12 ± 0.85 | 0.043 |

| eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 | 35/962 (3.6) | 7/77 (9.1) | 0.019 |

| Albumin, mg/dl | 4.3 ± 0.6 | 4.0 ± 0.6 | 0.013 |

Values are mean ± SD or n/N (%).

Abbreviations as in Table 2.

Severe case includes need for intensive care, endotracheal intubation, renal replacement therapy, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or death.

Discussion

In adults with CHD, we found a case/fatality ratio from COVID-19 of 2.3% (95% CI: 1.4% to 3.2%) among mostly symptomatic infections. This figure was harmonious with the reported cumulative world fatality rate of 2.2%, although mortality varied considerably by location (14). Early experience with the COVID-19 pandemic identified heart disease as a risk factor but likely implied heart failure, coronary atherosclerosis, cardiomyopathies, and PAH (15). Our data suggested that extrapolation to include adults with CHD could be problematic, because many did not have these acquired cardiovascular problems or other high-risk features. Yet, our findings confirmed noncardiac risk factors reported elsewhere, including obesity, diabetes, and pregnancy (16,17).

Older age was a risk factor for COVID-related death in the general population. Our population was skewed towards younger ages, which might have affected some comparisons. The case/fatality ratio tended to be higher in the older age tertile, and age was a univariate predictor by binary regression. Many patients with CHD were younger, particularly patients with a Fontan single ventricle, which might offer protection and explain some of the favorable outcomes in our study. In addition, the anatomic and/or physiological makeup of the population with CHD population was expected to differ by age, with more complex anatomy expected in younger groups but more complex physiology in older groups. Thus, it was plausible that elements defining stage C or D in younger individuals differed from older patients, regardless of physiological status as determined by factors such as PAH, heart failure, or cyanosis, which clearly affected outcome.

Anatomic complexity in the absence of advanced physiological status did not seem to increase risk, consistent with published experience (8,18). For example, a patient with noncyanotic Fontan physiology without heart failure or arrhythmia did not appear to be at higher risk for COVID-19 death or severe infection compared with someone without CHD with comparable comorbidities, although many CHD providers might have predicted otherwise. However, there was inherent heterogeneity within the CHD spectrum, which encompassed a range of anatomic and physiological states, and some patients did fall into high-risk categories.

Despite limited data, recommendations based on sensible assumptions from what is known about the CHD community of patients have been published (10,11). Only 2 previous publications addressed COVID-19 in the CHD population from areas with high early incidence. The first, from Italy, reported that clinical event rates were not high, and there were no deaths. However, most patients had clinically suspected virus rather than confirmed infection by PCR (7). In the second, a recent a study of 53 PCR-positive subjects with CHD who received care in New York City, there were 3 (6%) deaths (8). Those at highest risk of death or severe infections were adults with advanced physiological stages (C and D) (9). The present study, which was approximately 20-fold higher than these previous publications, showed a case/fatality ratio similar to that of the general population (19).

Concern for myocardial damage from these and other viruses is inherently justifiable.

Historical data from previous viral epidemics confirmed adverse pulmonary and cardiovascular effects in the patient population with CHD (20, 21, 22). Cardiac injury from these challenges might have resulted from an overwhelming immune inflammatory cytokine response, direct viral invasion of cardiomyocytes, or poor myocardial oxygenation from severe hypoxia due to lung injury (23). These mechanisms might have plausibly complicated patients with CHD who were already prone to myocardial dysfunction, limited myocardial oxygenation, or pulmonary vascular disease. Yet. it could also be postulated that pre-conditioning in CHD paradoxically protects the myocardium to such stresses, and thus lessens the overall impact on the myocardium (12). We found little risk from systolic dysfunction or valve dysfunction, although our assessments of these were subjective and not uniformly assessed among centers. However, we did find significant risk in those with previous heart failure admission, which was consistent with other reports of CHD and PAH (24,25).

Our data confirmed that cyanosis and PAH, especially when combined (Eisenmenger syndrome), portends a high rate of adverse events. This was not surprising because of the reduced functional capacity, multiorgan consequences of chronic cyanosis and the limited reserve of these patients (26, 27, 28, 29). Increased risk from COVID-19 in PAH was documented (30). It was less clear whether cyanosis or PAH conveyed the most vulnerability; our limited experience suggested that cyanosis might be the stronger risk factor. We found that 6% of patients with CHD required ICU admission, a lower rate than that observed in non-CHD hospitalized patients (31).

The spectrum of presenting symptoms of COVID-19 in our population was similar to those described in the general population, although fever was less frequent (44% vs. 90%) (32). Reasons for this discrepancy are not clear but likely reflect less vigorous reporting methods herein. Of note, 6% of patients were completely asymptomatic; diagnoses were made incidentally through COVID PCR testing before a procedure or after a known exposure. The increasing availability and access to PCR and serological testing as the months of the pandemic unfolded allowed for inclusion of mostly confirmed positive COVID-19 cases in our study compared with previous publications (7). However, the denominator in any case/fatality ratio remains fluid because it is dependent on multiple physiological, institutional, psychosocial, and even geopolitical factors.

Study limitations

Our study could not determine the rate of infection among adults with CHD, because it was impossible to accurately measure the size of the population from which to base our case load. All patients in our study were followed by CHD centers, meaning the study was susceptible to referral bias and could thus have included more complicated patients with CHD and/or worse COVID-19 infections. The prevalence of death among adults with CHD who were infected but did not have access to specialized CHD care could not be determined. We included 60 asymptomatic patients; this implied there were likely other asymptomatic carriers among the population, although the prevalence of asymptomatic infections was unknown. The preceding limitations suggested that the true case/fatality ratio might actually be lower. It could be argued also that our sample included those with better access to care, and therefore, they had better outcomes than others not accounted for herein. In addition, we had predominantly American participation with lower participation from adult CHD centers with different socioeconomics and health care delivery models and could not confidently generalize our findings to patients globally.

Because we identified 24 COVID-19 related deaths, risk factor analysis was limited, and potential effects of confounding were more difficult to explore. Specifically, multivariate regression or risk score modeling was limited to study-only specific potential confounding. Due to referral bias, our sample might have had over-representation of sicker or more complex patients, including asymptomatic patients with who had PCR testing before procedures. This might partly explain our paradoxical finding of a slightly lower mortality among those with complex lesions (Table 4). A recent change in case complexity among inpatient CHD services during the pandemic was shown (33).

Our study focused on short-term death and serious complications and did not address potential medium- and long-term complications. Our identification of severe cases might facilitate future study of unfavorable physiological downstream effects. There were also known neuropsychiatric outcomes (33) and emerging information about longer-term consequences of patients hospitalized for COVID-19 (34,35).

Although we did not observe a relationship between our primary or secondary outcomes with race/ethnicity among the U.S. cohort, this should not be interpreted to suggest that Black and Hispanic adults with CHD were not disproportionately affected by COVID-19. Authors of a recent systematic review of 37 studies reported that African American/Black and Hispanic populations had higher rates of infection, hospitalization, and COVID-19−related deaths compared with non-Hispanic White populations, although case/fatality rates did not differ (36). It was likely that factors related to health care access, exposure (36), and racism (37) would also affect outcomes of Black and Hispanic adults with CHD living in the United States.

Conclusions

We found that the presence of a structural congenital heart defect did not necessarily portend an increased risk of mortality or morbidity from COVID-19 infection. This finding was important for both patients and providers worldwide who are now facing high numbers of cases throughout the population. Yet, recognizing the inherent heterogeneity across the CHD population, we identified several factors associated with mortality and severe infections. These showed that susceptibility might be based on physiological factors, not the complexity of the underlying anatomic defect. Our findings were harmonious with general population studies that showed risks associated with age, male sex, diabetes, and renal insufficiency.

Perspectives.

COMPETENCY IN PATIENT CARE: The case/fatality rate among adults with CHD who develop novel coronavirus infection is 2.3%. Mortality is more closely related to physiological factors such as cyanosis and pulmonary hypertension and to male sex, diabetes, and renal insufficiency, than to the complexity of cardiac defects.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK: Systematic efforts are needed to target preventive measures at patients with CHD who are at greatest risk of mortality and severe morbidity due to COVID-19.

Funding Support and Author Disclosures

The authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Acknowledgment

The authors are grateful for the statistical input of Jessica Minnier, assistant professor of biostatistics in the School of Public Health and Knight Cardiovascular Institute, Oregon Health and Science University.

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

References

- 1.Galloway J.B., Norton S., Barker R.D. A clinical risk score to identify patients with COVID-19 at high risk of critical care admission or death: an observational cohort study. J Infect. 2020;81:282–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.05.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noor F.M., Islam M.M. Prevalence and associated risk factors of mortality among COVID-19 patients: a meta-analysis. J Community Health. 2020;45:1270–1282. doi: 10.1007/s10900-020-00920-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tan W., Aboulhosn J. The cardiovascular burden of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) with a focus on congenital heart disease. Int J Cardiol. 2020;309:70–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.03.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams R.G., Pearson G.D., Barst R.J. Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Working Group on research in adult congenital heart disease. J Am College of Cardiol. 2006;47:701–707. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.08.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilboa S.M., Devine O.J., Kucik J.E. Congenital heart defects in the United States: estimating the magnitude of the affected population in 2010. Circulation. 2016;134:101–109. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.019307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Leary J.M., Siddiqi O.K., de Ferranti S., Landzberg M.J., Opotowsky A.R. The changing demographics of congenital heart disease hospitalizations in the United States, 1998 through 2010. JAMA. 2013;309:984–986. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sabatino J., Ferrero P., Chessa M. COVID-19 and congenital heart disease: results from a nationwide survey. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1774. doi: 10.3390/jcm9061774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis M.J., Anderson B.R., Fremed M. Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on patients with congenital heart disease across the lifespan: the experience of an academic congenital heart disease center in New York City. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.017580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stout K.K., Daniels C.J., Aboulhosn J.A. 2018 AHA/ACC Guideline for the management of adults with congenital heart disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:1494–1563. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Formigari R., Marcora S., Luciani G.B. Resilience and response of the congenital cardiac network in Italy during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2020;22:9–13. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0000000000001063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alsaied T., Aboulhosn J.A., Cotts T.B. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic implications in pediatric and adult congenital heart disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.017224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diller G.P., Gatzoulis M., Broberg C.S. Coronavirus disease 2019 in adults with congenital heart disease: a position paper from the ESC working group of adult congenital heart disease, and the International Society for Adult Congenital Heart Disease. Eur Heart J. 2020 Dec. 12 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa960. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Broberg C., McLarry J., Mitchell J. Accuracy of administrative data for detection and categorization of adult congenital heart disease patients from an electronic medical record. Pediatr Cardiol. 2015;36:719–725. doi: 10.1007/s00246-014-1068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johns Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Center Mortality Analyses. Available at: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu. Accessed January 10, 2021.

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Coronavirus Disease 2019: People with certain medical conditions. Available at: https//www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html. Accessed January 9, 2021.

- 16.Albitar O., Ballouze R., Ooi J.P., Sheikh Ghadzi S.M. Risk factors for mortality among COVID-19 patients. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;166:108293. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang T.S., Ding Y., Freund M.K. Prior diagnoses and medications as risk factors for COVID-19 in a Los Angeles Health System. medRxiv. 2020:20145581. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferrero P., Piazza I., Ciuffreda M. COVID-19 in adult patients with CHD: a matter of anatomy or comorbidities? Cardiol Young. 2020;30:1196–1198. doi: 10.1017/S1047951120001638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ioannidis J.P.A., Axfors C., Contopoulos-Ioannidis D.G. Population-level COVID-19 mortality risk for non-elderly individuals overall and for non-elderly individuals without underlying diseases in pandemic epicenters. Environ Res. 2020;188:109890. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ukimura A., Satomi H., Ooi Y., Kanzaki Y. Myocarditis associated with influenza A H1N1pdm2009. Influenza Res Treat. 2012;2012:351979. doi: 10.1155/2012/351979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gilca R., De Serres G., Boulianne N. Risk factors for hospitalization and severe outcomes of 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza in Quebec, Canada. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2011;5:247–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2011.00204.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bare I., Crawford J., Pon K., Farida N., Dehghani P. Frequency and consequences of influenza vaccination in adults with congenital heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 2018;121:491–494. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Madjid M., Safavi-Naeini P., Solomon S.D., Vardeny O. Potential effects of coronaviruses on the cardiovascular system: a review. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:831–840. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang F., Liu A., Brophy J.M. Determinants of Survival in Older Adults With Congenital Heart Disease Newly Hospitalized for Heart Failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2020;13 doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.119.006490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haddad F., Peterson T., Fuh E. Characteristics and outcome after hospitalization for acute right heart failure in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ Heart Fail. 2011;4:692–699. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.110.949933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ross E.A., Perloff J.K., Danovitch G.M., Child J.S., Canobbio M.M. Renal function and urate metabolism in late survivors with cyanotic congenital heart disease. Circulation. 1986;73:396–400. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.73.3.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perloff J.K., Rosove M.H., Child J.S., Wright G.B. Adults with cyanotic congenital heart disease: hematologic management. Ann Intern Med. 1988;109:406–413. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-109-5-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perloff J.K., Latta H., Barsotti P. Pathogenesis of the glomerular abnormality in cyanotic congenital heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 2000;86:1198–1204. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)01202-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Broberg C.S. Risk and resiliency: thrombotic and ischemic vascular events in cyanotic congenital heart disease. Heart. 2015;101:1521–1522. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-307849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pagnesi M., Baldetti L., Beneduce A. Pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular involvement in hospitalised patients with COVID-19. Heart. 2020;106:1324–1331. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2020-317355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Docherty A.B., Harrison E.M., Green C.A. Features of 20,133 UK patients in hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1985. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pascarella G., Strumia A., Piliego C. COVID-19 diagnosis and management: a comprehensive review. J Intern Med. 2020;288:192–206. doi: 10.1111/joim.13091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scognamiglio G., Fusco F., Merola A. Caring for adults with CHD in the era of coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: early experience in an Italian tertiary centre. Cardiol Young. 2020;10:1405–1408. doi: 10.1017/S1047951120002085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Butler M., Pollak T.A., Rooney A.G., Michael B.D., Nicholson T.R. Neuropsychiatric complications of covid-19. BMJ. 2020;371:m3871. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang C., Huang L., Wang Y. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet. 2021;397:220–222. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32656-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mackey K., Ayers C.K., Kondo K.K. Racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19- related infections, hospitalizations, and deaths: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Dec. 1 doi: 10.7326/M20-6306. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Churchwell K., Elkind M.S.V., Benjamin R.M. Call to action: structural racism as a fundamental driver of health disparities: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;142 doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]