Abstract

Analyzing immunomodulatory elements operating during antitumor vaccination in prostate cancer patients and murine models we identified IL-10-producing DC as a subset with poorer immunogenicity and clinical efficacy. Inhibitory TAM receptors MER and AXL were upregulated on murine IL-10+ DC. Thus, we analyzed conditions inducing these molecules and the potential benefit of their blockade during vaccination. MER and AXL upregulation was more efficiently induced by a vaccine containing Imiquimod than by a poly(I:C)-containing vaccine. Interestingly, MER expression was found on monocyte-derived DC, and was dependent on IL-10. TAM blockade improved Imiquimod-induced DC activation in vitro and in vivo, resulting in increased vaccine-induced T-cell responses, which were further reinforced by concomitant IL-10 inhibition. In different tumor models, a triple therapy (including vaccination, TAM inhibition and IL-10 blockade) provided the strongest therapeutic effect, associated with enhanced T-cell immunity and enhanced CD8+ T cell tumor infiltration. Finally, MER levels in DC used for vaccination in cancer patients correlated with IL-10 expression, showing an inverse association with vaccine-induced clinical response. These results suggest that TAM receptors upregulated during vaccination may constitute an additional target in combinatorial therapeutic vaccination strategies.

Keywords: therapeutic vaccination, dendritic cells, TAM receptors, MER, IL-10

1. Introduction

Therapeutic antitumor vaccination has shown limited clinical results, except in those settings with low tumor burden [1–3]. Despite a long effort in the development of immune-enhancing strategies, it has become evident that tumor inhibitory elements limit the efficacy of cancer immunotherapies [4, 5]. Consequently, blockade of T-cell checkpoint molecules has demonstrated an impressive clinical effect, leading to their approval for different tumors [6]. Interestingly, in this context vaccination has been shown to enhance the presence of tumor-specific lymphocytes and therefore, it would be expected to improve the response rate of these therapies [7, 8]. In addition to naturally occurring tumor-related immunosuppressive elements, there are therapy-induced regulatory elements that behave as negative feedback mechanisms. In the case of therapeutic vaccination, vaccines may harbor factors that curtail their efficacy. In this regard, in a vaccination clinical trial carried out in patients with prostate cancer, we reported poorer immunogenicity and clinical efficacy of dendritic cell (DC) vaccines expressing a tolerogenic module that, among other molecules, included IL-10 [9]. Similarly, in the murine setting we recently described the induction of an immunosuppressive DC subset characterized by the production of IL-10 (IL-10+ DC), which besides this cytokine, overexpresses inhibitory molecules such as PD-L1 [10]. Blockade of these molecules during therapeutic vaccination enhanced immunogenicity and antitumor activity. This suggests that identification of molecules potentially involved in the suppressive activity of these cells would allow their manipulation and concomitant vaccine improvement.

Preliminary characterization of IL-10+ DC revealed that, among different factors, Mertk and Axl mRNA were upregulated in these cells, suggesting a potential role for these molecules in the suppressive effect of this DC subset. MER and AXL, together with Tyro, belong to the family of TAM tyrosine kinase receptors [11]. The main ligands identified for these receptors are Gas6 and Pros1 [12], proteins that bind to TAM receptors by their carboxyl-terminal domain and to phosphatidylserine exposed on cells by their amino-terminal domain. In the field of cancer, TAM receptors have gained interest because they are commonly overexpressed in several solid and haematological tumors [13–16], leading to the activation of tyrosine kinase activity. Therefore, they may promote not only cell transformation and survival, but also chemoresistance, motility and invasion, functioning as oncogenic drivers [17], prompting the development of TAM inhibitors as direct anticancer drugs [18–22]. However, in addition to tumor cells, TAM receptors are physiologically expressed in monocytes/macrophages to control tissue repair and elimination of apoptotic cells [23]. By binding to phosphatidylserine expressed on apoptotic cells, TAM receptors expressed on macrophages facilitate clearance of these cells while simultaneously downregulating inflammatory processes during tissue repair [24–26]. This inhibitory role on inflammatory responses also operates in DC, where ligation of TAM receptors downregulates their maturation induced by TLR signals [27]. In a similar manner, TAM receptors behave as a feedback mechanism after ligation by Pros1 expressed by activated T-cells, thus limiting DC activation [28].

The increased Mertk and Axl mRNA levels observed in IL-10+ DC induced after vaccination, together with the role these receptors play in attenuating DC immunogenic properties, led us to hypothesize that TAM receptors could be playing a relevant role on the immunosuppressive effect of this DC subset. Moreover, since several TAM inhibitors have been developed as anticancer drugs, we reasoned that these inhibitors could be also useful in cancer immunotherapy during therapeutic vaccination. We thus analyzed how vaccines modulate MER and AXL expression in antigen presenting cells (APC), changes occurring in their expression in the tumor microenvironment, and finally, the effect that TAM receptor inhibition would have on vaccine immunogenicity and concomitant therapeutic efficacy.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Reagents

Peptides (purity > 95%), were purchased from Genecust (Luxembourg). OVA (low endotoxin) was from Hyglos (Germany). TAM receptor inhibitor RXDX-106 [29] was a kind gift of Ignyta (San Diego, CA; USA).

2.2. Mice

IL-10 reporter Vert-X (B6(Cg)-Il10tm1.1Karp/J) and IL-12 p40 reporter Yet40 (B6.129-Il12btm1.1Lky/J) mice were obtained from Jackson. OT-II (C57BL/6-Tg(Tcra-Tcrb)425Cbn/J) mice were a kind gift of Dr. I. Melero (CIMA, Pamplona, Spain). Female C57BL/6J were from Envigo (Barcelona, Spain). The mice were maintained in pathogen-free conditions and treated according to guidelines of the institution, after study approval by the review committee.

2.3. Tumor cell lines

MC38-OVA cells (a kind gift of Dr. I. Melero; CIMA) and B16-F10 cells (obtained from Dr. G. Kroemer; Paris, France) were grown in complete medium (RPMI 1640 plus 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics). Cell stocks from early passages created upon receipt and tested for mycoplasma were used for tumor experiments. Re-authentication of cells was not performed since receipt.

2.4. In vitro assays with RXDX-106

Bone marrow-derived DC (BMDC) were differentiated from precursors by culturing erythrocyte-depleted cells (2 x 105 cells/well) in 96-well plates with GM-CSF (20 ng/ml), replacing media every 2-3 days. At day 6, cells were treated with Imiquimod (3-10 g/ml) and RXDX-106 (0.1-1 μM), and after one day cells and supernatants were harvested for further analyses.

2.5. Immunization of mice

Mice were injected subcutaneously (s.c) with OVA (0.5 mg/mouse) (day 0) combined with Imiquimod cream (Meda-Aldara™; topical application; 2.5 mg/mouse; days 0-2) or poly(I:C) (Amersham; 50 μg/mouse; s.c.; day 0). When using peptide TRP2(180–188), mice received 50 μg of peptide (s.c.; days 0–2) and topical Imiquimod as above. Additionally, the mice received i.p. injection of anti-IL-10R (clone 1B1.3A; 500 μg), anti-PD-1 (clone RMP1–14; 200 μg) or the corresponding isotype control antibodies (all from BioXcell) the day of immunization, with or without 30 mg/kg of RXDX-106 (oral route) administered from day 0 to 5. In some experiments, C57BL6/J mice were injected i.v. with 5 x 106 CD4 cells obtained from OT-II mice after purification by negative selection (Miltenyi Biotec) and immunized 24 h later. Mice were sacrificed at day 2 for MER, AXL and IL-10 analyses and at day 7 for ELISPOT assays, and splenocytes or tumor-infiltrating cells were obtained for immune characterization.

2.6. Treatment of tumor-bearing mice

Mice with 5 mm MC38-OVA or B16-F10 tumors received 2 weekly cycles of OVA (intratumor; 0.5 mg/mouse) or TRP2(180–188) peptide (intratumor; 50 μg/mouse) combined with Imiquimod at day 0–2 as described above. Some groups received anti-IL-10R or isotype antibodies as above at days 0 and 7, whereas RXDX-106 was administered on days 0–5 of each cycle. Tumor volume was calculated using the formula: V= (length x width2)/2. Mice were euthanized after two weeks of treatment or if tumors reached 17 mm in diameter.

2.7. ELISPOT

The number of IFN-γ producing T-cells was determined by ELISPOT (BD-Biosciences) as described [30]. Splenocytes (5 x 105/well) were stimulated with peptide OVA(257–264), OVA(323–339) or TRP2(180–188) for 24 h and spot-forming cells were counted automatically.

2.8. ELISA

Levels of cytokines IL-12 p70 and TNF-α secreted by DC were determined by ELISA sets (BD-Biosciences) in culture supernatants according to manufacturer instructions.

2.9. Flow cytometry

After homogenization, splenocytes were first incubated with Fc Block™ (BD-Biosciences) for 10 minutes. TAM receptors were analyzed after staining with the following fluorochrome-labelled antibodies: anti-AXL-PE, MER-APC, CD11c-BV510, F4/80-BV421, CD11b-FITC, Ly6C-PerCP/Cy5.5, Ly6G-PE-Cy7, CD19 APC-Cy7, CD3-FITC and NKp46- PerCP/Cy5.5 (from Biolegend, except those targeting Ly6G (BD-Biosciences) and AXL (R&D)). Antigen presenting cells were analyzed by staining with anti-AXL-PE, MER-APC, IAb-PerCP/Cy5.5, CD11c-BV421, F4/80-BV650, Ly6C-Alexa700, CD86-BV510, PD-L1-1BV785, CD64-PE, (from Biolegend), Ly6G-BUV563, CD11b-BUV661 and CD80-BUV395 (from BD-Biosciences). When using tumor samples, they were incubated with collagenase/DNase for 15 minutes, homogenized and stained with the same antibody panel but also including anti-mouse CD45-APC-Cy7. T-cell responses induced by the treatment were analyzed after a 4 h stimulation of splenocytes with CD8 or CD4 epitope peptides, and staining with antibodies against, CD4-Alexa 700, CD8-PeCy7, CD107a-FITC (from Biolegend), CD3-BUV496 and CD25-BUV395 (from BD-Biosciences). Then cells were fixed and permeabilized and finally stained intracellularly with anti-IFN-γ-PE, TNF-α-BV510 and Foxp3-APC. They were also analyzed by using Kb/OVA(257-264)-PE, Kb/TRP2(180-188)-PE and Kb/ENV(574–581)-APC tetramers. In all cases, the promofluor 840 (maleimide, Promokine) was added to stain dead cells. Samples were acquired with FACSCantoII (Becton Dickinson) or with Cytoflex (Beckman Coulter) flow cytometers and analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc).

2.10. Immunohistochemistry

Frozen tissues were fixed in pre-cooled acetone for 6 minutes at room temperature (RT). Then, sections were blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide followed by an antibody diluent block (Dako) for 10 minutes at RT. Incubation with anti-CD3 (Abcam, 16669; 1:75) primary antibody was performed overnight at 4 °C. Finally, signal was detected by using the Advance™ HRP system (Dako). CD3+ T cells were quantified and are shown as number of positive cells per area.

2.11. Analysis of human data

Normalized gene expression measurements for human DC vaccine preparations were downloaded from the GEO (accession: GSE85698). Associations between MERTK and IL10 gene expression (N=93) or clinical responses for individuals and the mean gene expression of these genes at weeks 24 and 48 (N=18 and N=15, respectively) after the start of treatment were determined with a Spearman’s ranked correlation test. Data corresponding to IL-10 and MER expression in BDCA1+ and BDCA1+CD14+ cells were obtained from GEO (accession number GSE75042).

2.12. Statistical analyses

Immune parameters and tumor size were analyzed using Student’s t test and one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. P<0.05 was taken to represent statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. Vaccination with Imiquimod upregulates TAM receptor expression in IL-10+ DC

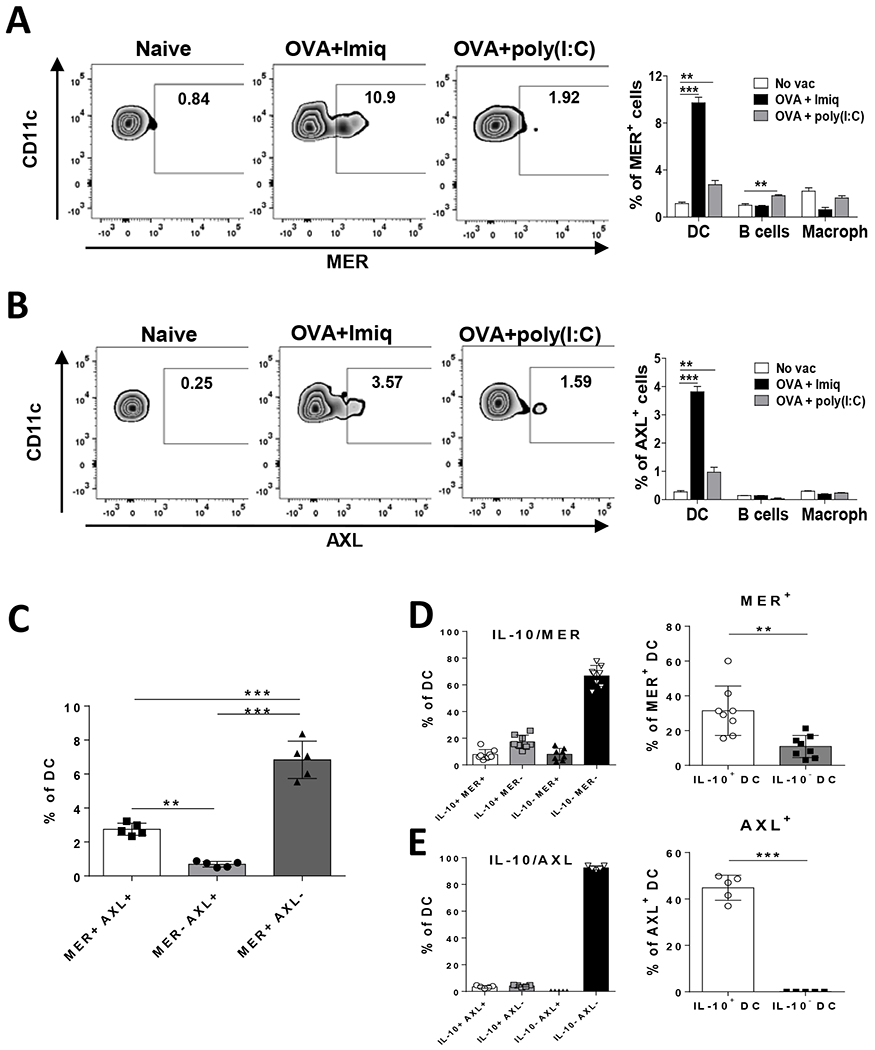

We described earlier that human DC vaccines expressing IL-10 [9] and vaccination protocols based on adjuvants inducing murine IL-10+ DC [10] are characterized by a poorer immunogenicity, suggesting the importance of identifying additional factors amenable to modulation in order to improve vaccine potency. Gene expression analyses identified higher levels of TAM receptor molecules Mertk and Axl in IL-10+ DC. Since they can down-regulate immunostimulatory functions of APC, we sought confirmation of their expression at the protein level in the vaccination setting. We compared the effect of vaccines containing OVA plus two different adjuvants, the TLR7 ligand Imiquimod, known to induce IL-10+ DC, or the TLR3 ligand poly(I:C), unable to induce IL-10+ DC upon vaccination [10]. The Imiquimod-containing vaccine induced the expression of MER in about 10% of splenic DC, above the 1% level observed in unvaccinated mice (P < 0.0001) (Figure 1A). By contrast, vaccination with poly(I:C) induced the expression of MER only in 2 % of DC (P = 0.0028 vs unvaccinated). Analysis of MER in other APC subsets showed neither expression on monocytes (data not shown), nor increase on macrophages, while a significant, but small, increase of MER induced by the poly(I:C) vaccine was seen in B-cells (P < 0.01 vs unvaccinated). Equivalent results were obtained when analyzing AXL, with more evident upregulation in DC from Imiquimod- than from poly(I:C)-vaccinated mice (Figure 1B). However, percentages of AXL+ DC (~4 % of DC) were lower than those obtained when analyzing MER. Interestingly, whereas the majority of AXL+ DC were also MER+, 60–70% of MER+ DC were negative for AXL, indicating an overall predominance of this MER+AXL− subset (Figure 1C). Despite reported expression on NK cells [31], we did not see any effect of vaccines on MER and AXL expression in splenic NK cells (data not shown).

Figure 1. Expression of TAM receptors MER and AXL in DC induced by vaccination.

C57BL/6J mice (n=5) were immunized with OVA + Imiquimod, OVA + poly(I:C) or left untreated. Two days later expression of MER (A) and AXL (B) was measured by flow cytometry. Left panels, representative plots of MER and AXL expression in DC. Right panels, summarized results in splenic DC, B cells and macrophages. Results are expressed as the percentage within each particular cell subset. (C) Identification of DC with single or double expression of MER and AXL in animals used the previous experiment. (D, E) Vert-X mice were immunized with OVA + Imiquimod and combined expression of IL-10 with MER (D) or AXL (E) was analyzed (left panels). At the same time, percentage of MER+ or AXL+ DC was calculated in IL-10+ and IL-10− DC (right panels). Results are representative of one out of 2–3 independent experiments. ** P<0.01; *** P<0.001

Since MER and AXL showed higher mRNA expression in IL-10+ DC [10], we analyzed MER and AXL in IL-10 reporter Vert-X mice, according to IL-10 production. In Imiquimod-vaccinated mice, MER+ DC were found in both the IL-10+ DC and IL-10− DC subsets, with similar proportions regarding total DC (7–8% in both cases with respect total DC) (Figure 1D, left panel). However, since the percentage of IL-10+ DC is much lower than that of IL-10− DC, MER+ DC were relatively more abundant in IL-10+ DC (31% of IL-10+ DC were MER+), compared to their proportion in IL-10− DC (10%) (P = 0.0023, MER+ DC in IL-10+ DC vs in IL-10− DC) (Figure 1D, right panel). On the other hand, AXL was almost exclusively expressed in IL-10+ DC (4–5% of total DC were AXL+) (Figure 1E, left panel). Thus, 44% of IL-10+ DC were AXL+ as opposed to less than 1% of AXL+ cells in IL-10− DC (P <0.0001, AXL+ DC in IL-10+ DC vs IL-10− DC) (Figure 1E, right panel), confirming thus for both TAM receptors previous results obtained at the mRNA level.

We next analyzed DC phenotype according to TAM expression, focusing our studies on MER, due to the higher percentage of MER+ cells as compared to AXL. No maturation differences were observed between MER+ and MER− DC (Supplementary Figure S1A). When considering both IL-10 and MER expression, IL-10− MER− DC (the most abundant group) expressed the highest values of maturation-associated markers CD86 and CD80. Interestingly, IL-10+ MER+ DC had intermediate values of CD86, higher than those observed in DC expressing either IL-10 or MER alone. However, the double-positive cells had the highest PD-L1 levels, in agreement with our previous data associating IL-10 and PD-L1 (Supplementary Figure S1B). These results suggest that among IL-10+ DC, MER expression defines a subset with a different phenotype.

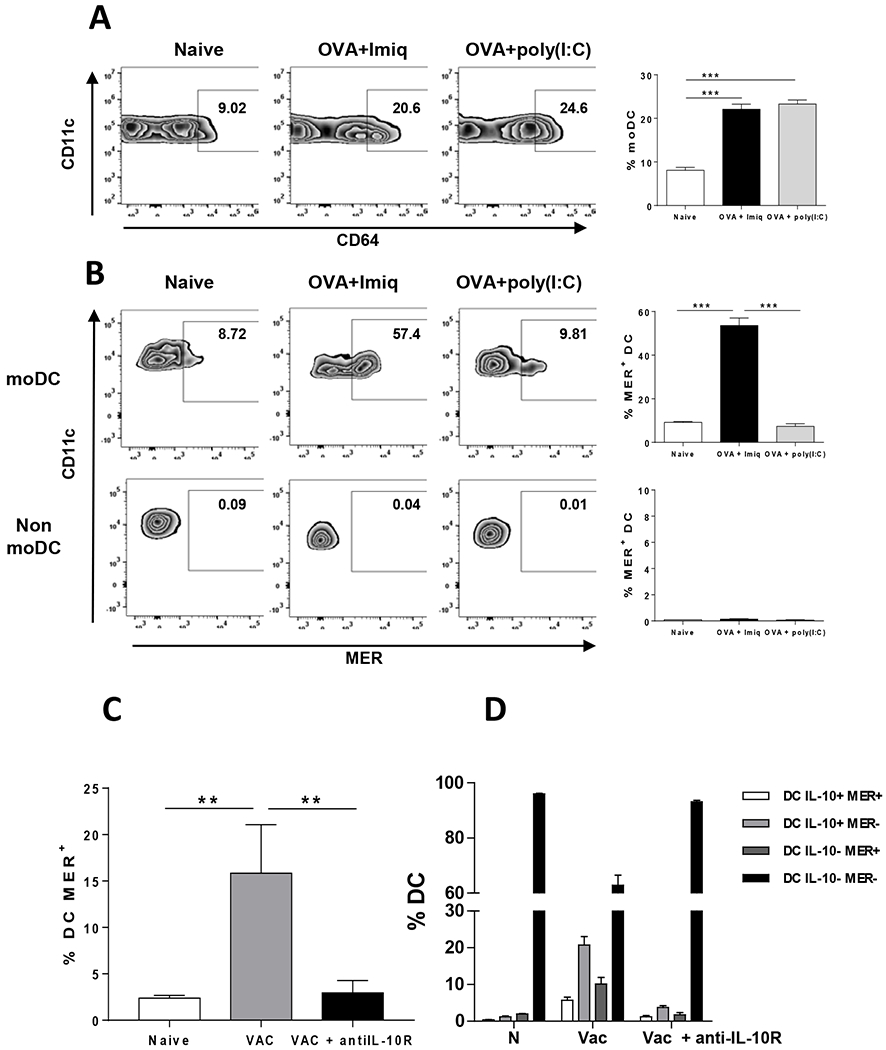

3.2. MER is induced in monocyte-derived DC in an IL-10-dependent manner

MER expression is usually higher in macrophages than in DC, and it has been considered a macrophage marker [32]. Moreover, in chronic viral infections, IL-10+ DC, like many macrophages, are of monocytic origin [33]. We thus analyzed in our vaccination setting whether MER+ DC, instead of deriving from a DC precursor, would derive from inflammatory monocytes (moDC). By using CD64 and Ly6C markers we determined that Imiquimod and poly(I:C) induced similar levels of moDC (Figure 2A). However, moDC from Imiquimod-vaccinated mice upregulated MER expression, not observed in moDC from poly(I:C) vaccinated mice or in other non-moDC subsets (Figure 2B). MoDC may acquire immunosuppressive features depending on their cytokine milieu [33], including type I IFN or IL-10. Since both Imiquimod and poly(I:C) are known for their capacity to induce type I IFN, we focused on IL-10. When mice were vaccinated with OVA + Imiquimod with IL-10 blockade a significant decrease in MER+ DC was observed (Figure 2C). Simultaneous analysis of MER and IL-10 showed that IL-10 blockade led to a decrease of MER+ DC both in IL-10+ and IL-10− DC subsets (Figure 2D), resulting in a DC distribution more similar to that observed in unvaccinated mice and suggesting a dependence of MER on IL-10. This effect was also associated with a more mature phenotype in most DC subsets (Supplementary Figure S2), although not so evident in IL-10− MER− DC, which already had the most mature phenotype. However, despite this decrease in MER expression, although the absolute numbers were low, around 20–25% of the remaining immunosuppressive IL-10+ DC still expressed MER, suggesting that the lack of complete downregulation of TAM receptors upon IL-10 signal blockade might open a window for an additional target to inhibit during vaccination.

Figure 2. MER is induced in monocyte-derived DC in an IL-10-dependent manner.

(A) Vert-X mice (n=4/group) were immunized with OVA + Imiquimod, OVA + poly(I:C) or left untreated. Two days later monocyte-derived splenic DC were analyzed based on CD64 and Ly6C expression. Left panels, representative plots of moDC in different groups. Right panel, summarized results of all mice. (B) Expression of MER in moDC and non-moDC in mice treated as in A. (C) Vert-X mice (n=4/group) were immunized with OVA + Imiquimod (Vac), OVA + Imiquimod plus anti IL-10R antibodies (Vac + antiIL-10R) or left untreated (Naive; N). Two days later splenic MER+ DC were measured. (D) Splenic DC subsets from mice treated as in C and defined according to IL-10 and MER expression were quantified. Results correspond to one out of two independent experiments. ** P<0.01; *** P<0.001

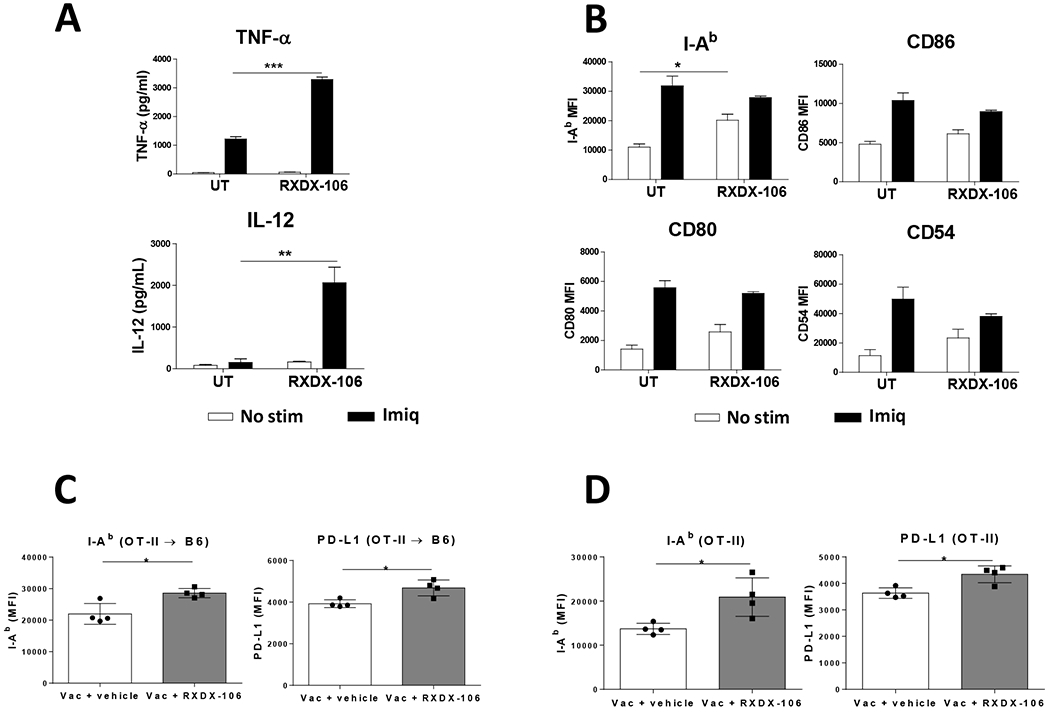

3.3. TAM inhibition enhances DC activation

Since in addition to DC maturation, vaccination also upregulates TAM receptors, we tested whether TAM receptor blockade during vaccination would modulate DC activation. In vitro stimulation of BMDC with Imiquimod increased MER expression, confirming previous in vivo results (Supplementary Figure S3A). When Imiquimod was added together with the TAM inhibitor RXDX-106, a higher TNF-α and IL-12 production was found. No increase in cytokine production occurred when adding only RXDX-106 (Figure 3A). Regarding maturation markers, RXDX-106 did not enhance their levels upon Imiquimod treatment, presumably due to already saturating levels. However, in the absence of Imiquimod, a trend of increased maturation levels, with statistical significance for MHC class II I-Ab molecules, was induced by RXDX-106 (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. TAM inhibition enhances DC activation in vitro and in vivo.

BMDC from C57BL/6J mice (4-5 replicates/condition) were stimulated in vitro with Imiquimod or left untreated, and in both cases, they were either incubated with TAM inhibitor RXDX-106 or with culture medium. One day later, (A) culture supernatants were harvested and TNF-α and IL-12 content measured by ELISA and (B) expression of surface activation markers determined by flow cytometry. C57BL/6J mice adoptively transferred with CD4 T-cells from OT-II mice (C) and OT-II mice (D) were immunized with OVA + Imiquimod with or without RXDX-106 and three days later expression of MHC class II molecules I-Ab and PD-L1 in splenic MER+ (C) or total (D) DC were measured by flow cytometry. Results correspond to mean fluorescence intensity for each marker. They are representative of two independent experiments. * P<0.05; ** P<0.01; *** P<0.001

When administered in vivo during vaccination, RXDX-106 did not modify maturation markers CD86 and CD80 on splenic DC. Similarly, PD-L1 did not change upon RXDX-106 administration (Supplementary Figure S3B). In equivalent vaccination experiments carried out in Vert-X and Yet40 mice, reporter for IL-10 and IL-12 p40, respectively, RXDX-106 did not modify the expression of these cytokines (Supplementary Figure S3C–D). Even when considering separately IL-10+ DC and IL-10− DC in Vert-X mice, no differences in the proportion of IL-10+ DC were observed in vaccinated mice receiving RXDX-106 treatment (data not shown). As in previous experiments, expression of maturation markers was not changed in IL-10+ DC or IL-10− DC (Supplementary Figure S3E), suggesting that in this setting TAM receptor blockade does not modify DC activation.

Pros1 produced by activated T-cells constitutes a feedback mechanism modulating DC activation upon TAM receptor ligation [28]. We hypothesized that 48 h may be a short window to allow T-cell activation and subsequent DC inhibition by Pros1+ T-cells. Moreover, the amount of DC receiving signals by vaccine-activated Pros1+ T-cells could be very low, thus precluding the detection of inhibitory effects when studying the whole splenic DC pool. Therefore, we repeated these experiments, but increasing OVA-specific T-cells through vaccination of B6 mice transferred with OT-II T-cells, and also analyzing DC at 72 h after vaccination. Although significant differences were not found when analyzing total DC (data not shown), analysis of MER+ DC showed a significant upregulation of I-Ab MHC class II molecules in mice treated with RXDX-106. Interestingly, higher expression of PD-L1 was also evident in MER+ DC from these mice (Figure 3C). To have a clearer effect, these experiments were repeated but directly immunizing OT-II mice. In this case, upregulation of I-Ab and PD-L1 was evident even when analyzing total DC (Figure 3D). These results indicate that inhibition of Imiquimod-induced TAM receptors enhances DC activation, evident in stimulatory antigen presenting molecules and cytokines, and in immunomodulatory molecules, suggesting the opportunity of combining different blockade strategies.

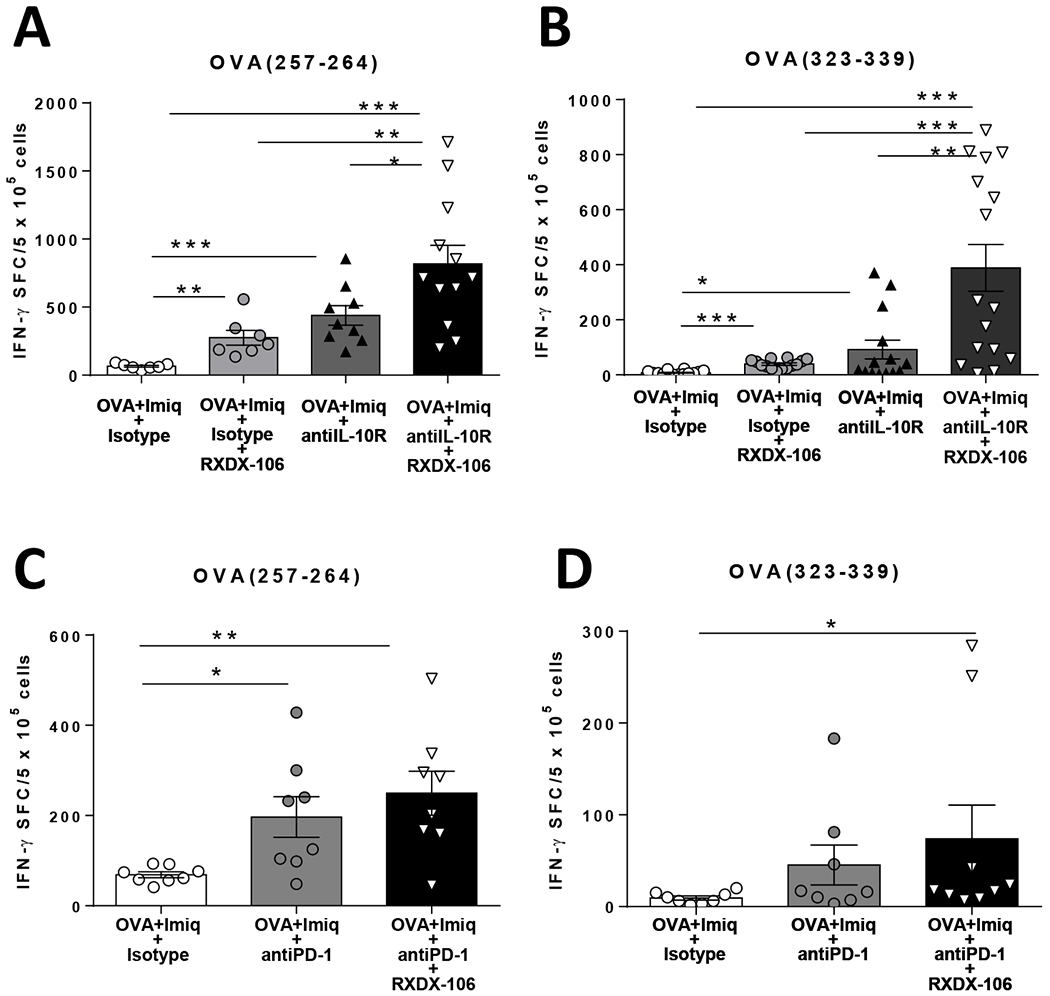

3.4. Combined blockade of TAM receptors and IL-10 improves vaccine immunogenicity

Simultaneous upregulation of TAM receptors and IL-10 in DC during vaccination, as well as their mutual association, prompted us to test the result of their blockade on vaccine immunogenicity. Single blockade of IL-10 or TAM receptors significantly increased immunogenicity of the OVA + Imiquimod vaccine in terms of CD8 T-cell responses against OVA(257–264) peptide and CD4 responses against peptide OVA(323–339), which were further enhanced when using the double blockade (Figure 4A–B). By contrast, immunization with poly(I:C) + OVA, a vaccine that did not generate IL-10+ DC [10] and does not benefit from IL-10 blockade [34], was not enhanced by TAM blockade (Supplementary Figure S4), in agreement with its poor capacity to upregulate MER and AXL on DC.

Figure 4. Combined blockade of TAM receptors and IL-10 improves vaccine immunogenicity.

C57BL/6J mice (n=4-6/group) were immunized with OVA + Imiquimod with or without simultaneous blockade of TAM receptors and IL-10. One week later they were sacrificed and splenic T-cell responses against the CD8 epitope OVA(257–264) (A) and CD4 epitope OVA(323–339) (B) were determined by IFN-γ ELISPOT. An experiment similar to that shown in A and B with the OVA + Imiquimod vaccine was carried out, but combining TAM and PD-1 blockade to measure CD8 (C) and CD4 (D) T-cell responses. Results correspond to the sum of two representative experiments. * P<0.05; ** P<0.01; *** P<0.001

Finally, since both vaccination and RXDX-106 upregulated PD-L1 on DC, we tested whether TAM blockade would improve vaccine immunogenicity in combination with anti-PD-1. There was a trend for higher responses when combining TAM inhibition and anti-PD-1, as compared with anti-PD-1 alone, but it did not reach statistical significance, when analyzing either CD8 or CD4 responses (Figure 4C–D).

3.5. Combined blockade of TAM receptors and IL-10 with vaccination has a superior antitumor therapeutic effect associated with stronger T-cell immunity

To test the therapeutic efficacy of the vaccine in combination with blockade of TAM receptors, we chose the MC38-OVA colon cancer model. In vitro, MER expression was not detected in MC38-OVA cells by flow cytometry (data not shown). These tumor cells showed poor sensitivity to RXDX-106, (IC50=0.18 μM in proliferation assays) (Supplementary Figure S5A), in agreement with published data for tumor cells and far above biochemical IC50 values [29]. In vivo, MER showed a predominant expression on tumor-infiltrating CD45+ leukocytes, including DC and macrophages, but not on CD45− cells, and this was not modified upon vaccination with OVA + Imiquimod (Supplementary Figure S5B–D). Regarding splenic cells of tumor-bearing mice, there were not differences with respect spleens from naive mice, but upon vaccination, MER was upregulated not only in DC (as occurred in vaccinated mice without tumors; Figure 1), but also in macrophages (Supplementary Figure S5E–F).

Next, B6 mice bearing 5 mm diameter MC38-OVA tumors were treated for two weeks, receiving immunizations with OVA + Imiquimod with or without RXDX-106. We included additional groups with anti-IL-10R. Tumor volume in mice treated with vaccine alone or with the different blockades significantly decreased when compared with the control group treated with isotype antibody. However, differences were more evident in groups containing the vaccine plus RXDX-106. Although IL-10 blockade did not provide any additional significant effect on tumor volume (Figure 5A), it had a clear impact on tumor rejection, since 92% of mice (13/14) in the group receiving the vaccine plus double blockade rejected their tumors, as opposed to 30–55% of tumors rejected in the other vaccinated groups.

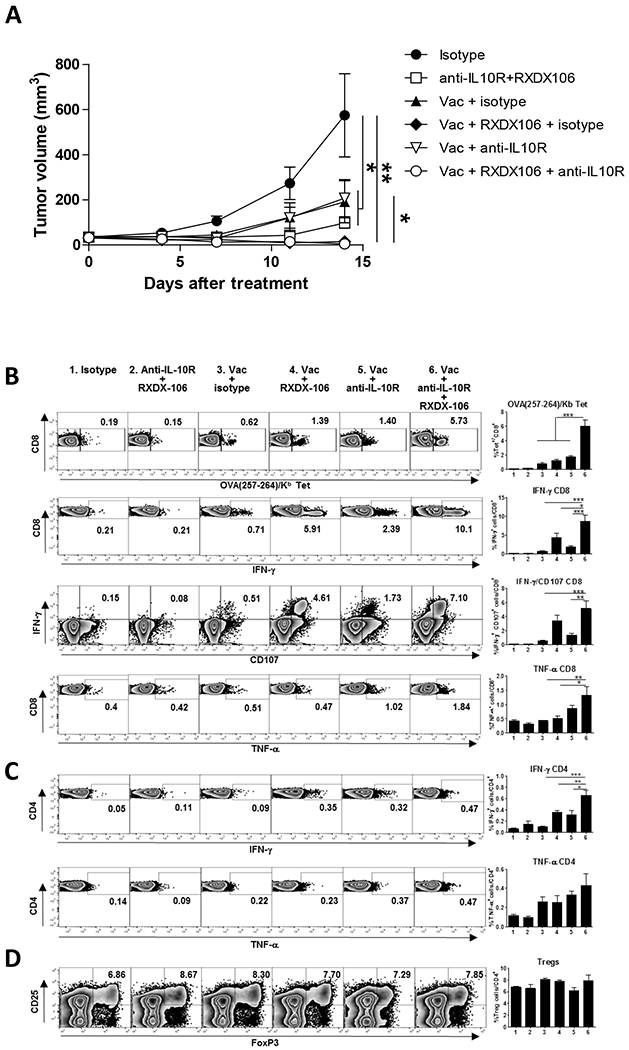

Figure 5. Combined blockade of TAM receptors and IL-10 with vaccination has superior antitumor effect associated with stronger T-cell immunity.

C57BL/6J mice bearing 5 mm MC38-OVA tumors were vaccinated with OVA + Imiquimod with or without administration of TAM inhibitor RXDX-106 and anti-IL-10R antibodies. As controls, mice receiving vaccine plus isotype control antibody, anti-IL-10R + RXDX-106, or only isotype control antibody were used. Tumor volume was measured until day 14 (A), when animals were sacrificed to measure immune parameters using splenic cells. (B) Percentage of CD8 T-cells specific for OVA(257-264), and of those expressing IFN-γ, CD107 and TNF-α after stimulation with OVA(257-264). (C) Percentage of CD4 T-cells expressing IFN-γ and TNFα- after stimulation with OVA(323-339). (D) Percentage of T regulatory cells among total CD4 T-cells. Data of tumor volume correspond to the sum of two independent experiments with 12-14 mice/group, whereas immune parameters correspond to four mice from a representative experiment. * P<0.05; ** P<0.01; *** P<0.001

Analyses of T cell responses in treated groups revealed background CD8 T-cell responses in isotype-treated mice and in mice treated with TAM and IL-10 blockade in the absence of vaccination. In the vaccinated groups, the highest responses in terms of OVA(257–264)/Kb tetramer+ cells, as well as IFN-γ, TNF-α and CD107 expression after peptide stimulation of CD8 T-cells, were found in mice having simultaneous blockade of TAM and IL-10 (Figure 5B). Moreover, a higher proliferative response (Ki67+ cells) was observed in CD8 T-cells from mice treated with the tripe combination, which mainly corresponded to OVA tetramer+ cells (Supplementary Figure S6A). A similar effect was obtained when measuring IFN-γ production by CD4 T-cells, not so evident in the expression of TNF-α (Figure 5C). These treatments had only effect on vaccine-specific T cells, since no changes were observed when measuring responses against the endogenous MC38 epitope ENV(574–581), either when analyzing tetramer+ cells or cytokine production after peptide stimulation (Supplementary Figure S6B). Finally, although constitutive TAM expression has been reported in Treg cells [35], no changes in their proportions were observed among groups (Figure 5D). These results suggest that vaccination combined with double blockade of TAM and IL-10 has a more potent antitumor effect, associated with stronger tumor-specific immunity.

3.6. Combined blockade of TAM receptors and IL-10 with vaccination has a superior antitumor therapeutic effect in an aggressive tumor model

In addition to OVA vaccines, it was of interest to confirm these results in a relevant tumor model with endogenous tumors antigens. We thus used as vaccine the CD8 epitope peptide TRP2(180–188), expressed by B16-F10 melanoma cells. In this case, despite a lack of effect on vaccine immunogenicity of single TAM blockade, addition of IL-10 blockade to RXDX-106 improved vaccine immunogenicity not only over control mice receiving only the vaccine, but also over those receiving the vaccine and IL-10 blockade (Figure 6A). As in MC38-OVA tumors, despite a lack of detection of MER in B16-F10 tumor cells, RXDX-106 inhibited their in vitro proliferation (IC50 = 0.58 μM) (Supplementary Figure S7A). In vivo, MER was detected in CD45+ but not in CD45− cells in the tumor (data not shown) and, similar to the MC38-OVA model, vaccination upregulated its expression in splenic DC (Supplementary Figure S7B).

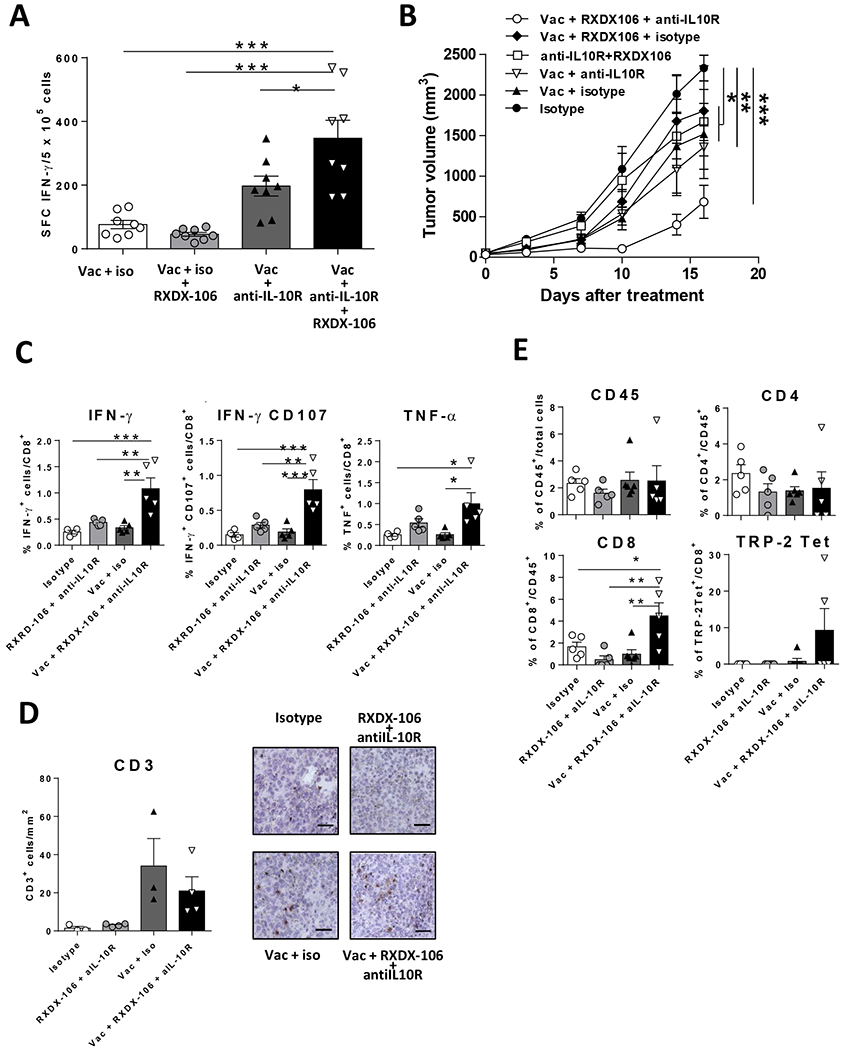

Figure 6. Combined blockade of TAM receptors and IL-10 with vaccination has superior antitumor effect in the aggressive B16-F10 model.

(A) C57BL/6J mice were immunized with TRP2(180-188) + Imiquimod with or without simultaneous blockade of TAM receptors and IL-10. One week later they were sacrificed and splenic T-cell responses against TRP2(180-188) were determined by IFN- ELISPOT. (B) C57BL/6J mice (n=8/ group) bearing 5 mm B16-F10 tumors were vaccinated with TRP2(180-188) + Imiquimod with or without administration of anti-IL-10R antibodies and TAM inhibitor RXDX-106. As controls, mice receiving vaccine plus isotype control antibody, anti-IL-10R + RXDX-106, or only isotype control antibody were used. Tumor volume was measured twice per week. (C) Spleens were obtained from tumor-bearing mice after one week of treatment and the percentage of CD8 T-cells expressing IFN-γ IFN-γ/CD107 and TNF-α after stimulation with TRP2(180-188) peptide was determined by flow cytometry. (D) Tumor sections were stained with anti-CD3 antibodies and the number of infiltrating CD3+ cells was counted. Data correspond to the mean of nine fields/tumor (left side). Representative images (right side) of the four treatment groups. The bar represents 50 m. (E) Tumors were obtained after treatment, homogenized and the percentage of CD45+ leukocytes, CD4, CD8 and TRP2(180-188) Tet+ T cells was measured by flow cytometry. * P<0.05; ** P<0.01; *** P<0.001

Regarding therapeutic effect, all vaccinated groups had a lower tumor volume. However, as opposed to results obtained in the MC38-OVA model, where IL-10 blockade provided a less clear benefit on tumor volume over vaccine plus RXDX-106, in this model, mice treated with vaccine plus the double blockade had the greatest tumor volume reduction (Figure 6B) showing the necessity of this combination for a more aggressive model. As occurred in the MC38-OVA model, therapeutic effect was associated with a robust antitumor immunity, evident for several CD8 T-cell effector functions (Figure 6C) analyzed in the spleen.

Regarding immune parameters in the tumor, image analyses showed that as opposed to unvaccinated groups, mice receiving the vaccine -with or without the double blockade- had a higher infiltration of CD3+ cells (Figure 6D). To better understand the immune response in the tumor we also used flow cytometry. Although similar levels of infiltrating CD45+ leukocytes and CD4+ T cells were observed in all groups, the percentage of CD8+ T cells was substantially and statistically significantly higher in mice treated with the triple combination of vaccine, RXDX-106 and anti-IL-10R than in the other groups (Figure 6E). Regarding TRP2(180–188)-specific cells detected by tetramer binding, in most animals these cells were below the limit of detection. However, in two out of five mice of the triple combination group receiving vaccine, RXDX-106 and anti-IL-10R, these cells were readily detected, with substantial levels above 15% of total CD8 T cells (Figure 6E). These results confirm the enhancing effect that the double blockade has on the immunogenicity and antitumor effect of the vaccine.

3.7. MER and IL-10 association in DC used in therapeutic vaccination in cancer patients

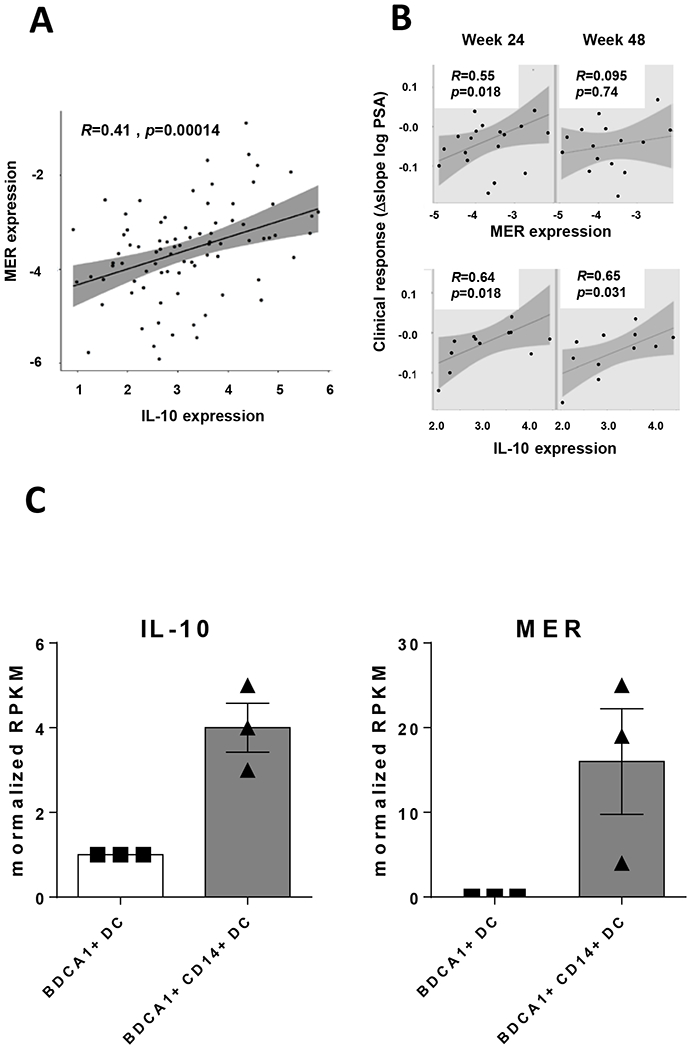

We finally studied the relevance of TAM receptors in therapeutic vaccination clinical trials carried out in cancer patients. Since data describing DC after vaccine administration were scarce, we consider the analysis of DC used as vaccines. We examined data obtained from 93 monocyte-derived DC preparations used as vaccines in a cohort of 18 prostate cancer patients [9]. These DC were matured by using LPS, a molecule that we previously demonstrated to induce IL-10+ DC in the murine vaccination setting [10], as well as IFN-γ. As mentioned earlier, IL-10 was part of a tolerogenic signature observed in DC that correlated inversely with clinical and immunologic response. These analyses showed that there was a positive significant correlation (R=0.41; P=0.00014) between IL-10 and MER expression (Figure 7A). Interestingly, when analyzing clinical responses (measured as the Δslope log PSA), there was a correlation with MER expression in DC at week 24 and with IL-10 at weeks 24 and 48 (Figure 7B).

Figure 7. Expression of IL-10 and MER in DC used as vaccines in cancer patients.

Gene expression of IL-10 and MER in (A) monocyte-derived DC preparations used to vaccinate a cohort of 18 patients with prostate cancer. (B) Association between MER and IL-10 expression in DC with clinical response. (C) Gene expression of IL-10 and MER in BDCA1+ DC and BDCA+CD14+ DC from three individuals.

In addition to this cohort, we analyzed primary blood BDCA1+ DC, cells used to vaccinate melanoma patients [36]. In this DC population, there is a subset of BDCA1+CD14+ DC with suppressive properties [37], that upon stimulation, showed lower expression of maturation markers and secreted higher IL-10 levels than BDCA1+CD14− DC, mimicking some features of our murine IL-10+ DC. Analyses of gene expression from a public dataset of BDCA1+CD14+ DC obtained from three donors confirmed higher IL-10 and MER expression levels in BDCA1+CD14+ DC (Figure 7C). These results suggest that also in the human vaccination setting, MER expression in DC may be associated with IL-10 production.

4. Discussion

Similar to tumor-associated suppressive elements targeted by current immunotherapies, immunomodulatory factors induced during vaccination may be amenable to manipulation, leading to stronger vaccines. Therefore, identification of molecules that restrain vaccine activity is an important goal. Our previous work indicated upregulated mRNA expression of TAM receptors Mertk and Axl in IL-10+ DC, cells with immunosuppressive effects [10]. Since TAM receptors control innate immunity [27], we analyzed them as a potential additional mechanism responsible for IL-10+ DC activity and as new targets for DC modulation. We found that adjuvants promoting IL-10+ DC generation (Imiquimod) trigger MER and, to a lower extent, AXL upregulation in DC. By contrast, poly(I:C), unable in vivo to induce IL-10+ DC, promoted low or nil upregulation of TAM receptors, despite its reported in vitro capacity to induce them (mainly AXL) [38]. Differences between in vivo and in vitro systems, as well as in the type of DC analyzed (splenic DC vs BMDC) may account for these discrepancies. TAM receptor upregulation was observed in both IL-10+ and IL-10− DC; however, their proportion was higher in IL-10+ DC, with MER predominating over AXL expression. In a chronic viral infection model, IL-10+ DC are generated from inflammatory monocytic precursors, which later acquire immunosuppressive features due to type I IFN. In our case, although Imiquimod- and poly(I:C)-based vaccines induced moDC similarly, and both are adjuvants known to induce type I IFN, only Imiquimod induced clear TAM expression. Interestingly, IL-10 blockade during vaccination decreased the number of MER+ DC, suggesting a role for IL-10 in MER upregulation. TAM receptor upregulation in innate immune cells depends on different stimuli, including TLR ligands, cytokines and glucocorticoids [26, 27, 38, 39]. Among cytokines, type I IFN, frequently induced by some TLR-ligands, is as a potent TAM inducer [27]. However, the poorer TAM upregulation induced by poly(I:C), suggests the necessity of additional factors such as IL-10. In this regard, MER upregulation in macrophages requires IL-10, although IL-10 alone is not sufficient, indicating again the necessity of other inducers [26]. Analysis of expression of MER and AXL suggests a tolerogenic environment favoring MER over AXL expression, which in turn predominates in a more inflammatory setting [38]. Both type I IFN [40–42] and glucocorticoids [43, 44] have been described as inducers of IL-10, reinforcing the potential role of this tolerogenic cytokine on MER upregulation.

Despite a clear effect of IL-10 blockade, a small percentage of DC remained MER+, suggesting a potential target for modulation, even in the presence of IL-10 inhibition. By using RXDX-106, a recently described pan-TAM inhibitor with immunomodulatory effects [29], we observed more activated DC in vitro and in vivo, although in this last case, effect of RXDX-106 on DC was evident only in the presence of high frequencies of vaccine-specific T-cells. The antitumor effect induced by this inhibitor is immune-mediated, by initially enhancing innate responses, associated with higher levels of MHC class IIhi cells, including DC and macrophages [29], a result in agreement with our observation of MHC class II upregulation in vitro and upon in vivo RXDX-106 administration during vaccination. According to the higher expression of antigen presenting molecules, we observed that TAM blockade enhanced CD4 and CD8 T-cell responses when using OVA, but not with TRP2(180–188) peptide, presumably due to the helper-independent nature of this epitope [45], which does not require MHC class II presentation. Furthermore, when combined with IL-10 blockade, it resulted in significantly stronger T-cell responses. This effect of RXDX-106 despite the low MER levels could be attributed to the potent immunosuppressive capacity of IL-10+ DC, as previously shown [10]. Alternatively, since RXDX-106 may inhibit other TAM receptors, this effect should be also considered, although AXL expression levels were always lower than those observed for MER. Moreover, in the B16-F10 model, vaccine induced more CD3+ T-cell infiltration in the tumor by immunohistochemistry, and flow cytometry revealed that the triple combination of vaccine, RXDX-106 and anti-IL-10R induced more CD8+ T-cell infiltration and in particular TRP2-tetramer positive T-cell infiltration compared to vaccine alone or double blockade alone (Fig 6 D & E). Thus, this combination facilitates antigen-specific CD8+ T-cells to enter the tumor microenvironment where they can potentially kill or inhibit tumor cells.

Regarding PD-L1, notwithstanding its upregulation by RXDX-106, combination of RXDX-106 with vaccine plus anti-PD-1 did not provide clear effects on immunization, although a trend of improvement was observed. This suggests that, despite its poor activity during vaccine priming of T-cells, this combination could still be of interest, since apart from effects on vaccine-induced T-cells, anti-PD-1 may act on other targets such as already existing antitumor T-cells. In this regard, combination of TAM inhibitors and PD-1 blockade has recently shown promising results [29, 46–49].

Results of antitumor therapeutic activity of combinations tested above paralleled those obtained in vaccination. In both the MC38-OVA and B16-F10 models, vaccination with or without single blockade had an intermediate effect, whereas a triple combination including vaccine, RXDX-106 and IL-10 blockade yielded the best antitumor results. However, IL-10 blockade was more necessary in the aggressive B16-F10 model. In the absence of vaccination, the double blockade (RXDX-106 + anti-IL-10R) also provided some activity. These results are in agreement with experiments carried out with RXDX-106 administration or MER antibody blockade in other tumors [29, 49], where MER blockade on APC triggers innate immunity through different mechanisms, like STING activation and MHC class II upregulation, leading to increased T-cell responses in the tumor environment.

Finally, to analyze the potential relevance of MER in the human antitumor vaccination setting, we studied a large dataset of 93 monocyte-derived DC preparations used in a clinical trial carried out in prostate cancer patients. A positive correlation was observed between MER and IL-10 (Figure 7), a molecule that was part of a tolerogenic gene module that inversely correlated with DC immunogenicity and clinical benefit [9]. Moreover, as for IL-10, MER expression inversely correlated with the clinical effect promoted by the DC vaccines. In a more reduced dataset of BDCA1+ DC, cells used to vaccinate melanoma patients, the BDCA1+CD14+ DC subset, known to possess suppressive capacity, also displayed higher IL-10 and MER levels. These human data, in agreement with those obtained in mice, indicate that MER is a common molecule in DC with tolerogenic properties, and suggest that it may be a relevant target in therapeutic vaccination in cancer patients. Recent results indicate MER expression on human T-cells, where as opposed to APC, it would behave as a co-stimulatory molecule [50]. The higher MER expression levels observed in DC from cancer patients who experienced poor responses to vaccination may suggest a prevailing inhibitory role over the co-stimulatory effect, although more data are still necessary in this regard [51]. Meanwhile, several TAM inhibitors have been developed, initially designed in some cases as direct antitumor drugs, with a few of them tested in clinical trials in patients with different tumors [52]. The identification of the immunomodulatory properties of these compounds indicates their dual mechanism of action and suggests that they may be suitable for combinatorial immunotherapies.

In summary, we have shown that the IL-10+ DC-inducing adjuvant Imiquimod promotes TAM receptor expression, mainly on IL-10+ DC, and this expression depends on IL-10. Association between IL-10 and MER expression has been observed in DC used in human vaccination trials. Since combined blockade of these immunosuppressive molecules not only enhances immune responses induced by vaccination but also provides a superior therapeutic antitumor effect, simultaneous inhibition of these elements should be considered for future therapeutic vaccination strategies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Authors thank Ignyta for providing TAM inhibitor RXDX-106 and Drs Melero and Kroemer for tumor cell lines.

Financial support

This work was supported by Instituto de Salud Carlos III co-financed by European FEDER funds (PI14/00343; PI17/00249), Fundación Bancaria La Caixa “Hepacare” project and the “Murchante contra el cáncer” initiative.

Abbreviations:

- DC

dendritic cells

- TAM

Tyro3, AXL, MER

- BMDC

Bone marrow-derived DC

- APC

antigen presenting cells

- moDC

monocyte-derived DC

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- [1].Kantoff PW, Higano CS, Shore ND, Berger ER, Small EJ, Penson DF, Redfern CH, Ferrari AC, Dreicer R, Sims RB, Xu Y, Frohlich MW, Schellhammer PF, Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer, N Engl J Med, 363 (2010) 411–422. 10.1056/NEJMoa1001294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Melero I, Gaudernack G, Gerritsen W, Huber C, Parmiani G, Scholl S, Thatcher N, Wagstaff J, Zielinski C, Faulkner I, Mellstedt H, Therapeutic vaccines for cancer: an overview of clinical trials, Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 11 (2014) 509–524. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Tan AC, Goubier A, Kohrt HE, A quantitative analysis of therapeutic cancer vaccines in phase 2 or phase 3 trial, J Immunother Cancer, 3 (2015) 48. 10.1186/s40425-015-0093-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Vasaturo A, Verdoes M, de Vries J, Torensma R, Figdor CG, Restoring immunosurveillance by dendritic cell vaccines and manipulation of the tumor microenvironment, Immunobiology, 220 (2015) 243–248. 10.1016/j.imbio.2014.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Binnewies M, Roberts EW, Kersten K, Chan V, Fearon DF, Merad M, Coussens LM, Gabrilovich DI, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Hedrick CC, Vonderheide RH, Pittet MJ, Jain RK, Zou W, Howcroft TK, Woodhouse EC, Weinberg RA, Krummel MF, Understanding the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) for effective therapy, Nat Med, 24 (2018) 541–550. 10.1038/s41591-018-0014-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hargadon KM, Johnson CE, Williams CJ, Immune checkpoint blockade therapy for cancer: An overview of FDA-approved immune checkpoint inhibitors, Int Immunopharmacol, 62 (2018) 29–39. 10.1016/j.intimp.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Massarelli E, William W, Johnson F, Kies M, Ferrarotto R, Guo M, Feng L, Lee JJ, Tran H, Kim YU, Haymaker C, Bernatchez C, Curran M, Zecchini Barrese T, Rodriguez Canales J, Wistuba I, Li L, Wang J, van der Burg SH, Melief CJ, Glisson B, Combining Immune Checkpoint Blockade and Tumor-Specific Vaccine for Patients With Incurable Human Papillomavirus 16-Related Cancer: A Phase 2 Clinical Trial, JAMA Oncol, 5 (2019) 67–73. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Chung V, Kos FJ, Hardwick N, Yuan Y, Chao J, Li D, Waisman J, Li M, Zurcher K, Frankel P, Diamond DJ, Evaluation of safety and efficacy of p53MVA vaccine combined with pembrolizumab in patients with advanced solid cancers, Clin Transl Oncol, 21 (2019) 363–372. 10.1007/s12094-018-1932-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Castiello L, Sabatino M, Ren J, Terabe M, Khuu H, Wood LV, Berzofsky JA, Stroncek DF, Expression of CD14, IL10, and Tolerogenic Signature in Dendritic Cells Inversely Correlate with Clinical and Immunologic Response to TARP Vaccination in Prostate Cancer Patients, Clin Cancer Res, 23 (2017) 3352–3364. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Llopiz D, Ruiz M, Infante S, Villanueva L, Silva L, Hervas-Stubbs S, Alignani D, Guruceaga E, Lasarte JJ, Sarobe P, IL-10 expression defines an immunosuppressive dendritic cell population induced by antitumor therapeutic vaccination, Oncotarget, 8 (2017) 2659–2671. 10.18632/oncotarget.13736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Rothlin CV, Carrera-Silva EA, Bosurgi L, Ghosh S, TAM receptor signaling in immune homeostasis, Annu Rev Immunol, 33 (2015) 355–391. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032414-112103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Stitt TN, Conn G, Gore M, Lai C, Bruno J, Radziejewski C, Mattsson K, Fisher J, Gies DR, Jones PF, et al. , The anticoagulation factor protein S and its relative, Gas6, are ligands for the Tyro 3/Axl family of receptor tyrosine kinases, Cell, 80 (1995) 661–670. 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90520-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Craven RJ, Xu LH, Weiner TM, Fridell YW, Dent GA, Srivastava S, Varnum B, Liu ET, Cance WG, Receptor tyrosine kinases expressed in metastatic colon cancer, Int J Cancer, 60 (1995) 791–797. 10.1002/ijc.2910600611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Graham DK, Salzberg DB, Kurtzberg J, Sather S, Matsushima GK, Keating AK, Liang X, Lovell MA, Williams SA, Dawson TL, Schell MJ, Anwar AA, Snodgrass HR, Earp HS, Ectopic expression of the proto-oncogene Mer in pediatric T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Clin Cancer Res, 12 (2006) 2662–2669. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].He L, Zhang J, Jiang L, Jin C, Zhao Y, Yang G, Jia L, Differential expression of Axl in hepatocellular carcinoma and correlation with tumor lymphatic metastasis, Mol Carcinog, 49 (2010) 882–891. 10.1002/mc.20664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hutterer M, Knyazev P, Abate A, Reschke M, Maier H, Stefanova N, Knyazeva T, Barbieri V, Reindl M, Muigg A, Kostron H, Stockhammer G, Ullrich A, Axl and growth arrest-specific gene 6 are frequently overexpressed in human gliomas and predict poor prognosis in patients with glioblastoma multiforme, Clin Cancer Res, 14 (2008) 130–138. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Graham DK, DeRyckere D, Davies KD, Earp HS, The TAM family: phosphatidylserine sensing receptor tyrosine kinases gone awry in cancer, Nat Rev Cancer, 14 (2014) 769–785. 10.1038/nrc3847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Holland SJ, Pan A, Franci C, Hu Y, Chang B, Li W, Duan M, Torneros A, Yu J, Heckrodt TJ, Zhang J, Ding P, Apatira A, Chua J, Brandt R, Pine P, Goff D, Singh R, Payan DG, Hitoshi Y, R428, a selective small molecule inhibitor of Axl kinase, blocks tumor spread and prolongs survival in models of metastatic breast cancer, Cancer Res, 70 (2010) 1544–1554. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Christoph S, Deryckere D, Schlegel J, Frazer JK, Batchelor LA, Trakhimets AY, Sather S, Hunter DM, Cummings CT, Liu J, Yang C, Kireev D, Simpson C, Norris-Drouin J, Hull-Ryde EA, Janzen WP, Johnson GL, Wang X, Frye SV, Earp HS 3rd, Graham DK, UNC569, a novel small-molecule mer inhibitor with efficacy against acute lymphoblastic leukemia in vitro and in vivo, Mol Cancer Ther, 12 (2013) 2367–2377. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Linger RM, Cohen RA, Cummings CT, Sather S, Migdall-Wilson J, Middleton DH, Lu X, Baron AE, Franklin WA, Merrick DT, Jedlicka P, DeRyckere D, Heasley LE, Graham DK, Mer or Axl receptor tyrosine kinase inhibition promotes apoptosis, blocks growth and enhances chemosensitivity of human non-small cell lung cancer, Oncogene, 32 (2013) 3420–3431. 10.1038/onc.2012.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Linger RM, Lee-Sherick AB, DeRyckere D, Cohen RA, Jacobsen KM, McGranahan A, Brandao LN, Winges A, Sawczyn KK, Liang X, Keating AK, Tan AC, Earp HS, Graham DK, Mer receptor tyrosine kinase is a therapeutic target in pre-B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Blood, 122 (2013) 1599–1609. 10.1182/blood-2013-01-478156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Brandao LN, Winges A, Christoph S, Sather S, Migdall-Wilson J, Schlegel J, McGranahan A, Gao D, Liang X, Deryckere D, Graham DK, Inhibition of MerTK increases chemosensitivity and decreases oncogenic potential in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Blood Cancer J, 3 (2013) e101. 10.1038/bcj.2012.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Scott RS, McMahon EJ, Pop SM, Reap EA, Caricchio R, Cohen PL, Earp HS, Matsushima GK, Phagocytosis and clearance of apoptotic cells is mediated by MER, Nature, 411 (2001) 207–211. 10.1038/35075603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Tibrewal N, Wu Y, D’Mello V, Akakura R, George TC, Varnum B, Birge RB, Autophosphorylation docking site Tyr-867 in Mer receptor tyrosine kinase allows for dissociation of multiple signaling pathways for phagocytosis of apoptotic cells and down-modulation of lipopolysaccharide-inducible NF-kappaB transcriptional activation, J Biol Chem, 283 (2008) 3618–3627. 10.1074/jbc.M706906200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Filardy AA, Pires DR, Nunes MP, Takiya CM, Freire-de-Lima CG, Ribeiro-Gomes FL, DosReis GA, Proinflammatory clearance of apoptotic neutrophils induces an IL-12(low)IL-10(high) regulatory phenotype in macrophages, J Immunol, 185 (2010) 2044–2050. 10.4049/jimmunol.1000017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Zizzo G, Hilliard BA, Monestier M, Cohen PL, Efficient clearance of early apoptotic cells by human macrophages requires M2c polarization and MerTK induction, J Immunol, 189 (2012) 3508–3520. 10.4049/jimmunol.1200662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Rothlin CV, Ghosh S, Zuniga EI, Oldstone MB, Lemke G, TAM receptors are pleiotropic inhibitors of the innate immune response, Cell, 131 (2007) 1124–1136. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Carrera Silva EA, Chan PY, Joannas L, Errasti AE, Gagliani N, Bosurgi L, Jabbour M, Perry A, Smith-Chakmakova F, Mucida D, Cheroutre H, Burstyn-Cohen T, Leighton JA, Lemke G, Ghosh S, Rothlin CV, T cell-derived protein S engages TAM receptor signaling in dendritic cells to control the magnitude of the immune response, Immunity, 39 (2013) 160–170. 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Yokoyama Y, Lew ED, Seelige R, Tindall EA, Walsh C, Fagan PC, Lee JY, Nevarez R, Oh J, Tucker KD, Chen M, Diliberto A, Vaaler H, Smith KM, Albert A, Li G, Bui JD, Immuno-oncological Efficacy of RXDX-106, a Novel TAM (TYRO3, AXL, MER) Family Small-Molecule Kinase Inhibitor, Cancer Res, 79 (2019) 1996–2008. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Llopiz D, Ruiz M, Villanueva L, Iglesias T, Silva L, Egea J, Lasarte JJ, Pivette P, Trochon-Joseph V, Vasseur B, Dixon G, Sangro B, Sarobe P, Enhanced anti-tumor efficacy of checkpoint inhibitors in combination with the histone deacetylase inhibitor Belinostat in a murine hepatocellular carcinoma model, Cancer Immunol Immunother, 68 (2018) 379–393. 10.1007/s00262-018-2283-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Caraux A, Lu Q, Fernandez N, Riou S, Di Santo JP, Raulet DH, Lemke G, Roth C, Natural killer cell differentiation driven by Tyro3 receptor tyrosine kinases, Nat Immunol, 7 (2006) 747–754. 10.1038/ni1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Gautier EL, Shay T, Miller J, Greter M, Jakubzick C, Ivanov S, Helft J, Chow A, Elpek KG, Gordonov S, Mazloom AR, Ma'ayan A, Chua WJ, Hansen TH, Turley SJ, Merad M, Randolph GJ, Gene-expression profiles and transcriptional regulatory pathways that underlie the identity and diversity of mouse tissue macrophages, Nat Immunol, 13 (2012) 1118–1128. 10.1038/ni.2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Cunningham CR, Champhekar A, Tullius MV, Dillon BJ, Zhen A, de la Fuente JR, Herskovitz J, Elsaesser H, Snell LM, Wilson EB, de la Torre JC, Kitchen SG, Horwitz MA, Bensinger SJ, Smale ST, Brooks DG, Type I and Type II Interferon Coordinately Regulate Suppressive Dendritic Cell Fate and Function during Viral Persistence, PLoS Pathog, 12 (2016) e1005356. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Llopiz D, Aranda F, Diaz-Valdes N, Ruiz M, Infante S, Belsue V, Lasarte JJ, Sarobe P, Vaccine-induced but not tumor-derived Interleukin-10 dictates the efficacy of Interleukin-10 blockade in therapeutic vaccination, Oncoimmunology, 5 (2015) e1075113. 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1075113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Zhao GJ, Zheng JY, Bian JL, Chen LW, Dong N, Yu Y, Hong GL, Chandoo A, Yao YM, Lu ZQ, Growth Arrest-Specific 6 Enhances the Suppressive Function of CD4(+)CD25(+) Regulatory T Cells Mainly through Axl Receptor, Mediators Inflamm, 2017 (2017) 6848430. 10.1155/2017/6848430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Schreibelt G, Bol KF, Westdorp H, Wimmers F, Aarntzen EH, Duiveman-de Boer T, van de Rakt MW, Scharenborg NM, de Boer AJ, Pots JM, Olde Nordkamp MA, van Oorschot TG, Tel J, Winkels G, Petry K, Blokx WA, van Rossum MM, Welzen ME, Mus RD, Croockewit SA, Koornstra RH, Jacobs JF, Kelderman S, Blank CU, Gerritsen WR, Punt CJ, Figdor CG, de Vries IJ, Effective Clinical Responses in Metastatic Melanoma Patients after Vaccination with Primary Myeloid Dendritic Cells, Clin Cancer Res, 22 (2016) 2155–2166. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Bakdash G, Buschow SI, Gorris MA, Halilovic A, Hato SV, Skold AE, Schreibelt G, Sittig SP, Torensma R, Duiveman-de Boer T, Schroder C, Smits EL, Figdor CG, de Vries IJ, Expansion of a BDCA1+CD14+ Myeloid Cell Population in Melanoma Patients May Attenuate the Efficacy of Dendritic Cell Vaccines, Cancer Res, 76 (2016) 4332–4346. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Zagorska A, Traves PG, Lew ED, Dransfield I, Lemke G, Diversification of TAM receptor tyrosine kinase function, Nat Immunol, 15 (2014) 920–928. 10.1038/ni.2986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Cabezon R, Carrera-Silva EA, Florez-Grau G, Errasti AE, Calderon-Gomez E, Lozano JJ, Espana C, Ricart E, Panes J, Rothlin CV, Benitez-Ribas D, MERTK as negative regulator of human T cell activation, J Leukoc Biol, 97 (2015) 751–760. 10.1189/jlb.3A0714-334R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Sharif MN, Tassiulas I, Hu Y, Mecklenbrauker I, Tarakhovsky A, Ivashkiv LB, IFN-alpha priming results in a gain of proinflammatory function by IL-10: implications for systemic lupus erythematosus pathogenesis, J Immunol, 172 (2004) 6476–6481. 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.6476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Wilson EB, Yamada DH, Elsaesser H, Herskovitz J, Deng J, Cheng G, Aronow BJ, Karp CL, Brooks DG, Blockade of chronic type I interferon signaling to control persistent LCMV infection, Science, 340 (2013) 202–207. 10.1126/science.1235208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Teijaro JR, Ng C, Lee AM, Sullivan BM, Sheehan KC, Welch M, Schreiber RD, de la Torre JC, Oldstone MB, Persistent LCMV infection is controlled by blockade of type I interferon signaling, Science, 340 (2013) 207–211. 10.1126/science.1235214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Rea D, van Kooten C, van Meijgaarden KE, Ottenhoff TH, Melief CJ, Offringa R, Glucocorticoids transform CD40-triggering of dendritic cells into an alternative activation pathway resulting in antigen-presenting cells that secrete IL-10, Blood, 95 (2000) 3162–3167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Mozo L, Suarez A, Gutierrez C, Glucocorticoids up-regulate constitutive interleukin-10 production by human monocytes, Clin Exp Allergy, 34 (2004) 406–412. d. 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.01824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Llopiz D, Huarte E, Ruiz M, Bezunartea J, Belsue V, Zabaleta A, Lasarte JJ, Prieto J, Borras-Cuesta F, Sarobe P, Helper cell-independent antitumor activity of potent CD8 T cell epitope peptide vaccines is dependent upon CD40L, Oncoimmunology, 2 (2013) e27009. 10.4161/onci.27009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Holtzhausen A, Harris W, Ubil E, Hunter DM, Zhao J, Zhang Y, Zhang D, Liu Q, Wang X, Graham DK, Frye SV, Earp HS, TAM Family Receptor Kinase Inhibition Reverses MDSC-Mediated Suppression and Augments Anti-PD-1 Therapy in Melanoma, Cancer Immunol Res, 7 (2019) 1672–1686. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-19-0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Kasikara C, Davra V, Calianese D, Geng K, Spires TE, Quigley M, Wichroski M, Sriram G, Suarez-Lopez L, Yaffe MB, Kotenko SV, De Lorenzo MS, Birge RB, Pan-TAM Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor BMS-777607 Enhances Anti-PD-1 mAb Efficacy in a Murine Model of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer, Cancer Res, 79 (2019) 2669–2683. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-2614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Caetano MS, Younes AI, Barsoumian HB, Quigley M, Menon H, Gao C, Spires T, Reilly TP, Cadena AP, Cushman TR, Schoenhals JE, Li A, Nguyen QN, Cortez MA, Welsh JW, Triple Therapy with MerTK and PD1 Inhibition Plus Radiotherapy Promotes Abscopal Antitumor Immune Responses, Clin Cancer Res, 25 (2019) 7576–7584. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-0795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Zhou Y, Fei M, Zhang G, Liang WC, Lin W, Wu Y, Piskol R, Ridgway J, McNamara E, Huang H, Zhang J, Oh J, Patel JM, Jakubiak D, Lau J, Blackwood B, Bravo DD, Shi Y, Wang J, Hu HM, Lee WP, Jesudason R, Sangaraju D, Modrusan Z, Anderson KR, Warming S, Roose-Girma M, Yan M, Blockade of the Phagocytic Receptor MerTK on Tumor-Associated Macrophages Enhances P2X7R-Dependent STING Activation by Tumor-Derived cGAMP, Immunity, (2020). 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Peeters MJW, Dulkeviciute D, Draghi A, Ritter C, Rahbech A, Skadborg SK, Seremet T, Carnaz Simoes AM, Martinenaite E, Halldorsdottir HR, Andersen MH, Olofsson GH, Svane IM, Rasmussen LJ, Met O, Becker JC, Donia M, Desler C, Thor Straten P, MERTK Acts as a Costimulatory Receptor on Human CD8(+) T Cells, Cancer Immunol Res, 7 (2019) 1472–1484. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Peeters MJW, Rahbech A, Thor Straten P, TAM-ing T cells in the tumor microenvironment: implications for TAM receptor targeting, Cancer Immunol Immunother, 69 (2020) 237–244. 10.1007/s00262-019-02421-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Myers KV, Amend SR, Pienta KJ, Targeting Tyro3, Axl and MerTK (TAM receptors): implications for macrophages in the tumor microenvironment, Mol Cancer, 18 (2019) 94. 10.1186/s12943-019-1022-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.