Abstract

Objective

This study used a programme logic model to describe the inputs, activities and outputs of the ‘10,000 Lives’ smoking cessation initiative in Central Queensland, Australia.

Design

A programme logic model provided the framework for the process evaluation of ‘10,000 Lives’. The data were collected through document review, observation and key informant interviews and subsequently analysed after coding and recoding into classified themes, inputs, activities and outputs.

Setting

The prevalence of smoking is higher in the Central Queensland region of Australia compared with the national and state averages. In 2017, Central Queensland Hospital and Health Services set a target to reduce the percentage of adults who smoke from 16.7% to 9.5% in the Central Queensland region by 2030 as part of their strategic vision (‘Destination 2030’). Achieving this target is equivalent to 20,000 fewer smokers in Central Queensland, which should result in 10,000 fewer premature deaths due to smoking-related diseases. To translate this strategic goal into an actionable smoking cessation initiative, the ‘10,000 Lives’ health promotion programme was officially launched on 1 November 2017.

Result

The activities of the initiative coordinated by a senior project officer included building clinical and community taskforces, organising summits and workshops, and regular communications to stakeholders. Public communication strategies (e.g., Facebook, radio, community exhibitions of ‘10,000 Lives’ and health-related events) were used to promote available smoking cessation support to the Central Queensland community.

Conclusion

The ‘10,000 Lives’ initiative provides an example of a coordinated health promotion programme to increase smoking cessation in a regional area through harnessing existing resources and strategic partnerships (e.g., Quitline). Documenting and describing the process evaluation of the ‘10,000 Lives’ model is important so that it can be replicated in other regional areas with high prevalence of smoking.

Keywords: public health, social medicine, preventive medicine, health policy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study considered a standard evaluation framework (logic model) to describe the programme.

Multiple sources of data were collected and included to describe the process of the programme.

The plan for impact evaluation of the programme is discussed in the article.

Some outputs may have been omitted due to lack of systematic documentation of all activities within the project field notes.

Introduction

Tobacco smoking remains the leading avoidable risk factor that contributes to the burden of death and disease in Australia. The 2015 Australian Burden of Disease Study estimated that 9.3% of the total disease burden, 13.3% of all deaths and 443,235 disablity-adjusted life years were related to tobacco use.1 2 In Queensland, the northeast state of Australia, leading causes of deaths are lung cancer, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) and coronary heart diseases, which have a strong link with tobacco smoking.3 In 2016, 12% of the adult population were daily smokers in Australia,4 whereas 14.5% of adults in Queensland5 and 16.7% of adults in Central Queensland (CQ) (the central regional district of Queensland) smoked daily.6 CQ had the fourth highest smoking prevalence among all 15 hospital and health services catchment regions in Queensland; South West (inner regional area) had the highest (21.6%) and the Sunshine Coast (close to the capital city, Brisbane) had the lowest rate (10.3%).7 Reasons for the higher smoking prevalence in CQ may include the higher proportion of the population who experience socioeconomic disadvantage, compared with the state average.7 8 Priority populations for smoking cessation assistance identified within CQ include pregnant women (17.0% smoking prevalence),9 Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples (Australia’s Indigenous people groups)5 and people living in particular local government areas within CQ, such as Gladstone 19.1% and Rockhampton 17.7% smoking prevalence.7 8

Tobacco control and smoking cessation programmes are a shared responsibility between the Federal Government and the States and Territories in Australia.10 The State and Territory governments implement many tobacco control and smoking cessation programmes. Queensland has performed as one of the best states in Australia for tobacco control activities in recent years.11 The daily smoking rate in Queensland declined from 17.9% in 2002 to 10.3% in 2020.12 Programmes and policies delivered by the Queensland Government including the Quitline service,13 antismoking mass media campaigns and smoke-free policies and laws have together contributed to maintaining a downward trend in the daily smoking rate in Queensland over the last few decades.14 However, a significantly higher rate of adult smoking than the state average has persisted in some regional areas like the CQ region.9 This might be due to a higher baseline smoking prevalence and suboptimal use of available interventions (e.g., Quitline) by the regional and rural people who smoke (Quitline monthly data, 2014–2019).

The higher prevalence of smoking in CQ compared with the whole of Queensland led Central Queensland Hospital and Health Service (CQHHS) to prioritise smoking cessation while formulating the region’s strategic health vision (known as ‘Destination 2030’) through a 6-month consultation process with CQ health personnel, consumers, priority groups and community partners.15 As part of ‘Destination 2030’,15 CQHHS set a goal to reduce the adult daily smoking prevalence from 16.7% to 9.5% in CQ by 2030. Accomplishing this goal would be equivalent to 20,000 fewer smokers in CQ, which was estimated to result in 10,000 lives that would be saved from premature death due to smoking-related diseases because half of all long-term smokers die from a smoking-related disease.16 The strategic goal was translated into an actionable health promotion initiative to increase smoking cessation, which was named ‘10,000 Lives’.17 The name of the ‘10,000 Lives’ initiative builds on the previously highly successful ‘10,000 Steps Rockhampton’ programme, which promoted physical activity in Rockhampton.18 19 The popularity of ‘10,000 Steps Rockhampton’ helped branding ‘10,000 Lives’ and increasing recognition of the programme among the partners and the community. Besides, the lesson learnt from the process evaluation of ‘10,000 Steps Rockhampton’ assisted us to develop a working model for achieving the goals of the ‘10,000 Lives’ initiative.18 19

Tobacco control and smoking cessation are priorities of federal and state governments (e.g., Queensland) in Australia, yet there are always budget constraints for preventive health promotion.20 As such, it is imperative to consider how to leverage off existing funded programmes with small iterative changes and budget. A low-cost and locally initiated programme like ‘10,000 Lives’ is one such example, where this principle is being applied, with the aim of improving the health and well-being of the community. Completing a process evaluation of ‘10,000 Lives’ was undertaken so that others can benefit from the shared learning experience and to identify elements that were implemented well and which were less successful and could be improved. Process evaluations of the national campaign for smoking cessation in Australia are documented rigorously.21–25 Some targeted smoking cessation campaigns have been evaluated for their impact and outcomes.26 27 However, we could not find any similar evaluations of smoking cessation programmes that used a logic model in the scientific literature. This paper documents the process evaluation of ‘10,000 Lives’ so that researchers, health professionals and policy makers can use this information for future programme planning.

Aim

This study aims to describe the inputs (planning, resources and costs, and partners), activities and outputs of the ‘10,000 Lives’ initiative of Central Queensland, Australia.

Method

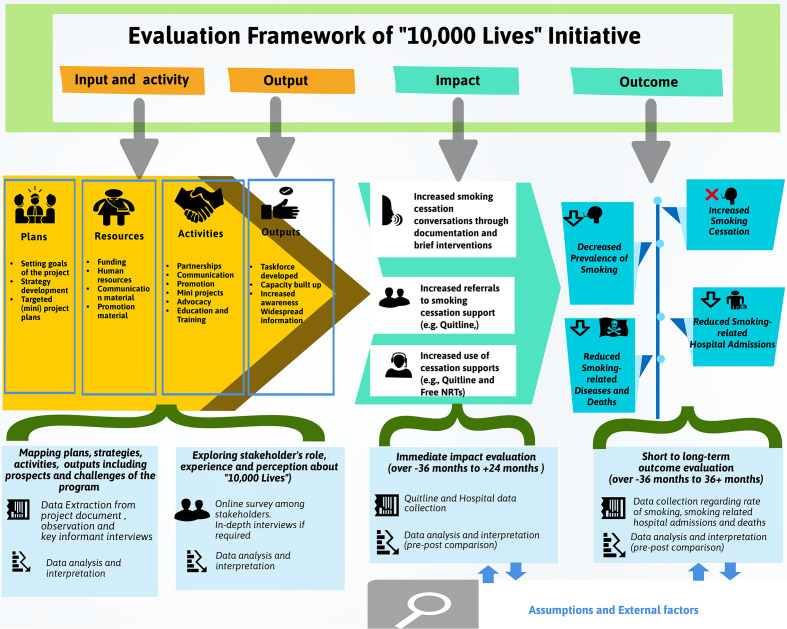

An evaluation plan was formulated to investigate the inputs, activites, outputs, impact and outcome of the ‘10,000 Lives’ initiative. A programme logic model, adapted from a standard health promotion evaluation framework,20 was developed for the evaluation plan. The evaluation framework was discussed among stakeholders who attended the ‘10,000 Lives’ summit in Rockhampton, Australia, in November 2018. We have chosen this model because this has guided understanding the programme input for ‘10,000 Lives’ but also the programme evaluation, where process, impact and outcome assessment can be clearly delineated (figure 1). However, this paper focuses on describing the inputs (planning, resources and cost, and partnership), activities and outputs of the initiative.

Figure 1.

Logic model for evaluation of ‘10,000 Lives’ initiative.

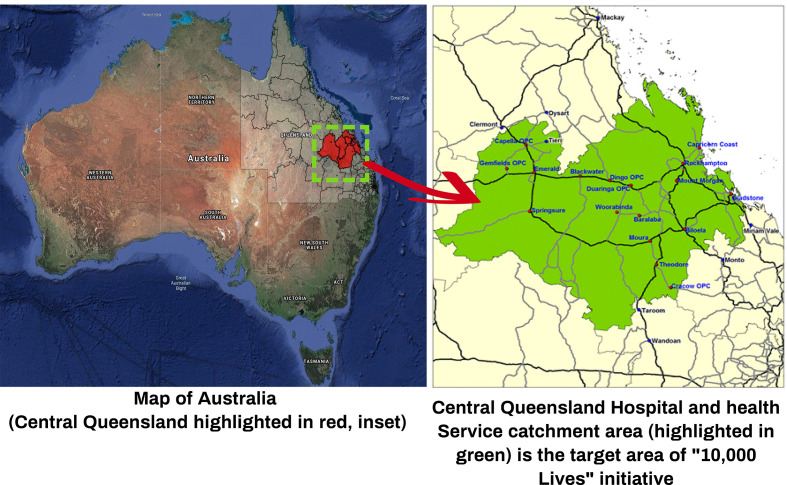

Target population of the ‘10,000 Lives’ initiative

The target population for the ‘10,000 Lives’ initiative is all smokers living in the service catchment area of CQHHS (figure 2), which includes 12 public hospitals in CQ.6 In 2017, the population of the CQ region was ~220,000 people (4.5% of the Queensland population and 0.9% of the Australia population).28 There were 54,722 families (74,201 households) in 2017; the median age was 34.9 years; 65% of the population were aged between 15 and 64 years.29 Approximately 6% of the population are Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islanders (Australian Indigenous people).8 The rate of smoking is higher among these population groups compared with the overall population due to the legacy of colonisation.30 The rate of homelessness was 41.0 per 10,000 persons. The median total personal income per year was A$35,017, with 50.2% having the highest level of schooling of year 11 or 12 (or equivalent). In CQ, 25.7% of the population were in the most disadvantaged quintile and 10.1% of the population were in the least disadvantaged quintile, whereas in Queensland, 20% of the population were in most disadvantaged quintile and 20.0% in the least disadvantaged quintile in 2017.8 Compared with the whole state of Queensland, CQ has a higher burden of the social determinants of poor health, including low-income households, early exit from school, unemployment and mental health issues. These sociodemographic factors contribute to the higher prevalence of smoking in this region.31 According to a state-wide survey in the year preceding the launching of ‘10,000 Lives’, an estimated ~28,000 adults who smoke resided in CQ.7 The daily smoking prevalence was highest (17.4%) in the 30–44 years age group. Also, the prevalence was high (18.5%) among the most disadvantaged quintile.7

Figure 2.

Study area map; ‘10,000 Lives’ initiative’s catchment area. Map showing the ‘10,000 Lives’ initiative’s target area (highlighted in green), which is the service catchment area of Central Queensland Hospital and Health Service (CQHHS). Red dots are indicated for the hospitals of CQHHS (source: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/maps/mapto/centralqld).

Study design, data collection and analysis

We conducted an exploratory investigation by critically appraising the project plan, partnership development, communication strategies, targeted project activities and overall health promotion activities for smoking cessation covered by the ‘10,000 Lives’ initiative. Data were collected retrospectively for the period between July 2017 (initiation of planning) up to December 2019 (26 months after the official launch of ‘10,000 Lives’) from field notes, project documentation notes, relevant policy documents and key informant interviews with project personnel.

A generic search was performed of relevant websites (ie, Queensland Health: www.health.qld.gov.au, CQ Health: www.health.qld.gov.au/cq, Department of Health of Australian Government: www.health.gov.au and Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: www.aihw.gov.au) for relevant policy documents and social media pages (e.g, Facebook) for information about smoking cessation campaigns active during the study timeframe.

Data were extracted from these sources and imported into NVivo,32 and then cleaned, coded and classified into five themes: plans, resources and cost, partnerships, activities and outputs. A narrative synthesis and summary interpretation was completed, and these are presented in the results section. The data sources and collection methods are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of data sources and collection method for each evaluation topic

| Themes | Data sources | Collection method |

| Inputs | ||

| Planning | Project planning documents and policy document ‘Destination 2030’ | Document review and internet search. |

| Resource | Project management documents. | Document review. |

| Partnership | Project planning and management documents, and key informant interviews. | Document review and key informant interviews. |

| Activities | Project management documents, master file for project management, key informant interviews, working group documents, websites and social media. | Document and content review, websites, social media, observation and key informant interviews. |

| Outputs | Project management documents, master spread sheet, stakeholders meeting documents, attendance sheet and key informant interviews. | Document review, Key informant interviews |

| Anticipated impact and outcome | Project management documents, policy documents and key informant interviews. | Project document review, policy documents review and key informant interviews. |

Patient and public involvement

We used routine data source for process evaluation of the programme. Individual participants were not involved in this study.

Result

Table 2 lists the key findings about the inputs (planning, resources and cost, and partnerships), activities and outputs of the ‘10,000 Lives’ initiative in first 26 months after its launch. We described further the result according to the findings from different parts of the logic model framework (i.e., inputs, activities and outputs).

Table 2.

Description of project planning, resources, partnerships, activities and outputs in first 26 months of project launched

| Inputs | Activities | Outputs | ||

| Planning | Resources and cost | Partnerships development | ||

Aims and objectives

Strategies

Guiding principle

Preset milestones

|

Human resource

Communication material

Promotion material

Materials for exhibition

Cost

|

Implementing intervention

Advocacy

Research and evaluation

|

Organised summit and forum

Developed taskforces

Campaigned and promoted smoking cessation interventions

Advocated policy

Implemented mini projects

|

Numbers of different outputs are shown in below tables (tables 4 and 5) |

CQ, Central Queensland; CQHHS, Central Queensland Hospital and Health Service.

Input: planning

At the programme planning stage (July–August 2017), Central Public Health Unit (CQPHU), with the help of the Service Integration Coordinator of the CQ Mental Health Alcohol and Other Drugs Services, developed a project proposal to establish a smoking cessation taskforce in CQ. The project proposal33 stated the objectives of the initiative as:

‘1. Establish a 10,000 Lives Taskforce: The taskforce will form the backbone of the project and through collective impact with the support of a wide range of community stakeholders large scale social change will be achieved. (“Collective impact” is a structured and disciplined approach to bringing cross-sector organisations together to focus on a common agenda that result in long-lasting improvement.).

2. Establish a team of clinical champions to engage key stakeholders for example, G.P.’s and provide health promotion activities, intervention and education to the broader community’.

The aim was subsequently reflected in ‘Destination 2030’.15 The initial plan considered strategies that adhered to the following guiding principles: (1) population approach of delivering a sustained, effective and comprehensive initiative for all, (2) whole system approach of harnessing the many inter-related factors that can contribute to improving health and well-being, (3) evidence-based approach of integrating knowledge from research evidence into implementation (e.g., evidence review of effective smoking cessations and partnership with academic institute for process evaluation), (4) reducing inequality by addressing the differences in health status in the community through recognising and responding to the vulnerable groups (e.g., the groups who have higher smoking prevalence), (5) working in partnership with government departments, community members, non-government organisations (NGOs) and academic stakeholders, (6) building capacity by developing an adequate number of skilled and empowered people and (7) effective implementation and evaluation for ensuring the platform to track the collective impact.33 For implementing the approaches, multiple and specific mini-projects were planned to target priority groups. For example, plans were formulated to give more attention to specific geographical areas (e.g., Gladstone and Woorabinda) and populations (eg, mine workers and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people) since the higher rate of smoking was observed among these populations. Ambitious milestones were set during programme planning including ‘a reduction of ~3000 smokers by 2020’, ‘a reduction of~14,000 smokers by 2025’ and ‘a reduction of~20,000 smokers by 2030’.33

Input: resources and costs

A senior project officer (SPO; administrative officer grade 5) was recruited in December 2017 to coordinate the planned activities and manage the implementation of the programme strategies. Other resources used in the project included communication materials (e.g., posters and leaflets, emails, news, website and social media content), promotion materials (e.g., information containing postcards, coffee cups, fridge magnets, water bottles and bags), materials required for mobile stalls to display the project activities in community or health events (e.g., display table and carbon monoxide breath testing for smokers), organising summits and workshops and ground signage. The approximate cost for running the programme for 24 months (January 2018–December 2019) was A$280,748 including the amount A$64,164 for the research and evaluation component (table 3). The initiative was approved by the CQHHS board and solely funded by CQHHS.

Table 3.

Monetary cost spent for ‘10,000 Lives’ initiative in 24 months (January 2018–December 2019) after launch

| Item of cost | Amount in Australian dollar |

| Labour cost (human resource) | $199,600.0 |

| Non-labour cost (materials, supplies, travel and so on) | $16,984.0 |

| Evaluation and research cost (PhD project) | $64,164.0 |

| Net cost | $280,748.0 |

In addition to the direct resource and costs, the initiative used in-kind support from the CQPHU for administrative activities including administration staff support and operational support during the period between starting the programme planning in July 2017 and the official launch of the initiative in November 2017. Also, the initiative used the existing resources available for smoking cessation in CQ that included combination of 12-week-free nicotine replacement therapies and telephone counselling via the Queensland Quitline’s Intensive Quit Support Program, subsidised smoking cessation pharmacotherapies through the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, Queensland Health’s Quality Improvement Payment (an incentive programme for clinicians) and the collaborative support from existing smoking cessation programmes (i.e., ‘Quit for You…Quit for Baby’, ‘Quit for You’, ‘Yarn to Quit’ and B.strong).

Input: partnerships

Developing partnerships and involving stakeholders in the implementation of ‘10,000 Lives’ was a key strategy of the initiative. A strategic partnership was made with the Queensland Quitline13 for enhancing the promotion of their existing Intensive Quit Support Program, which was available to rural, regional and remote communities with a higher than average smoking prevalence and accessing a monthly report to track Quitline registrations and participation status for smokers in CQ. Extensive in-kind support was provided by the board and chief executive of CQHHS by arranging the project fund, and the Preventive Health Branch of Queensland Health by giving strategic advice and advocacy for implementing the smoke-free policies. Partnerships were built with different units and programmes within CQHHS (e.g., oral health, mental health and ‘CQ Youth Connect’), community organisations (e.g., Rotary,34 a foundation for youth mental health called ‘Headspace’,35 a targeted brief intervention training programme for Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people named ‘B.strong’,36 a health promotion initiative for Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people called ‘Deadly Choices’,37 local councils (city council and local government staff) and an NGO supporting and developing businesses and projects in CQ called ‘Capricorn Enterprise’38 to promote and support smoking cessation activities for their staff and client population (patient, youth, community and Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people who smoke). The project collaborated with the University of Queensland for academic support for the programme evaluation. Partnerships were developed with ‘Cancer Council Queensland’39 for conducting training and workshops for the local clinicians, social workers and volunteers who were interested in supporting the initiative. The local Primary Health Network actively collaborated with ‘10,000 Lives’ initiative by promoting the initiative’s interventions (e.g., referral to Quitline and smoking cessation advice to patients who smoke) to general practitioners (GPs). Local sports clubs and radio stations also supported the initiative to promote the available smoking cessation interventions to their audience.

Activities

The SPO coordinated the activities of ‘10,000 Lives’ under the guidance of the director of CQPHU. The SPO took a preset plan and continuously adapted strategies (described in planning section) for implementing the programme. The following range of activities were delivered to increase smoking cessation in CQ:

Organising tobacco summits to develop partnerships with clinicians, GPs, social workers, local council and industry staff, and local politicians.

Establishing a clinical and community organisation taskforce for smoking cessation to identify clinical and community organisation personnel to become a champion for smoking cessation. CQHHS clinicians were encouraged to conduct inpatient hospital and healthcare facility-based documentation and brief intervention (Brief smoking cessation advice and referral embedded opportunistically into clinical practice.) via a standardised ‘Smoking Cessation Clinical Pathway (SCCP)’40 form among patients who smoke and to refer them to Quitline for accessing the Intensive Quit Support Program. The SCCP is an evidence-based decision support tool for screening smoking status and delivering a brief intervention to patients for smoking cessation. Community champions were encouraged to promote the Quitline programme and other smoking cessation support (e.g., My QuitBuddy app) to people who smoke.

Promoting smoking cessation through emails, newsletters, local radio, social media pages (i.e, Facebook), digital billboard and ground signage, and exhibiting in various community expos and health-related events. The SPO explored various communication pathways to promote the available smoking cessation support, particularly the Quitline programme. These included: conducting events on the local radio station (‘Triple M’), posting messages on Facebook pages (‘10,000 Lives’, CQHHS and ‘Triple M’ Facebook pages), local newspapers (The Morning Bulletin and Gladstone Observer) and in the daily news and weekly bulletin of CQHHS and e-newsletters for GPs and electronic billboard display in the centre of the main city of the CQ region (ie, Rockhampton CBD) (figure 3).

Advocating for smoke-free policies and programmes that could support smokers to quit. For example, the initiative established the ground signage and delivered tear off flyers promoting smoke-free healthcare in each of the hospital and community health campuses of CQHHS.

Implementing mini-projects to give extra attention to priority populations. For example, a film competition on ‘smoke-free teens’ was organised to deliver a youth-centric smoking cessation message designed by youth for youth, and a workshop was conducted by the SPO to introduce carbon monoxide breath monitors with Gumma Gundoo Indigenous Maternal & Infant Care Outreach team41 to increase awareness of the adverse effects of antenatal smoking on mother and baby among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander pregnant women.

Figure 3.

Examples of communication materials used in ‘10,000 Lives’ initiative.

Outputs

The quantitative output measures from the ‘10,000 Lives’ activities are shown in tables 4 and 5. Overall, the ‘10,000 Lives’ initiative conducted seven smoking cessation summits and one Tackling Tobacco Forum, promoted and celebrated World No Tobacco Day regionally, completed at least 20 education sessions for newly recruited CQHHS staff and conducted a combined smoking cessation workshop for the clinical and community champions. The SPO encouraged all the clinicians of CQHHS to attend the Smoking Cessation Masterclasses conducted by Queensland Health (Metro South HHS and Metro North HHS), with 70 clinicians completing, and a 3-day training course on nicotine addiction and smoking cessation,42 which was completed by six clinicians. Forty Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander volunteers were trained in performing brief intervention for smoking cessation conducted by the Menzies School of Health Research (B.strong).36 The ‘10,000 Lives’ initiative was exhibited in 12 community expos and 9 health-related events(e.g., World Cancer Day and World COPD day). The initiative implemented two mini-projects for priority population (Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander pregnant women and younger people). The ‘10,000 Lives’ collaborated with 15 different organisations including hospital and health service, regional councils, university, community organisations and other initiatives to promote smoking cessation in CQ. The SPO shared updated resources and information about smoking cessation to ~3400 staff of different partner organisations through emails and 4800 staff of CQHHS through posting in the daily news and a weekly bulletin called ‘The Drift’. As a result of communication through email, phone call, posting messages and in-person meetings by the SPO, at least seven clinical champions, two community champions, two political champions and a champion GP centre became actively involved and worked on the ground as the smoking cessation taskforce in CQ.

Table 4.

Occurrence of different activities and events implemented by ‘10,000 Lives’ initiative in first 26 months

| Event name | Frequency (N) |

| Smoking cessation summits organised | 7 |

| ‘World No Tobacco Day’ campaign (including a tobacco forum) | 2 |

| Number of mini-projects implemented for priority populations | 2 |

| Film competition with the theme of smoking cessation for young people, organised | 1 |

| Attended health event with ‘10,000 Lives’ stall | 9 |

| Attended community expo and event with ‘10,000 Lives’ stall | 12 |

| Brief education sessions delivered to newly recruited CQHHS staff | 20 |

| In-person meeting conducted | 97 |

| Facebook pages (10,000 Lives CQ, CQ Health and Triple M central Queensland) discussed posts | 206 |

| Occasional share of the updated information and resources to CQHHS staff through daily news and the weekly bulletin (Drift) | 4800 |

| Occasional emails with updated information and resources to the personnel from partner organisations other than CQHHS | 3409 |

CQ, Central Queensland; CQHHS, Central Queensland Hospital and Health Service.

Table 5.

Numbers of partners and champions contacted and numbers who supported the ‘10,000 Lives’ initiative in first 26 months

| Group/organisation | No. of contacted | No. of champions*/supporter†/ partner‡/participants§ identified (n (%)) |

| Clinical staff* | 133 | 7 (5.3) |

| Community service staff* | 26 | 2 (7.7) |

| GP centres* | 76 | 1 (1.3) |

| Regional and local council staff† | 15 | 6 (40) |

| Politicians† including minister, MP, mayor, councillors | 24 | 24 (100) |

| Organisations‡ for collaboration | 18 | 15 (83.3) |

| Clinicians§ for having smoking cessation masterclass training | 133 | 70 (52.6) |

| Students/teens§ registered for film competition | 21 | 6 (28.6) |

| Indigenous volunteers§ trained for brief intervention training by B.strong collaborated by ‘10,000 Lives’. | 90 | 40 (40) |

| Total | 536 | 171 (31.9) |

*Champion: the people or the unit who routinely worked for smoking cessation, kept regular communication with feedback to senior project officer of ‘10,000 Lives’ of his smoking cessation activities.

†Supporter: provided support and did advocacy for ’10,000 Lives’ initiative.

‡Partners: collaborated and worked together with ‘10,000 Lives’ initiative.

§Participants: participated in training/programme/competition.

GP, General Practice; MP, Member of Parliament.

Discussion

This article explains why and how the initiative was implemented and describes the way it operated over the 26-month period following its official launch in November 2017. This study also outlines how success of the programme will be measured.

The ‘10,000 Lives’ initiative was launched to reduce the daily smoking rate in CQ, which is higher than the state average. Policymakers realised the high disease burden that is due to smoking and included the ambitious aim to reduce the smoking rate to 9.5% by 2030 in the Destination 2030 plan. The implementing organisation of the initiative is the local public health unit, which explored the existing and available smoking cessation support available in its region. A number of effective tobacco control and smoking cessation interventions were already available in the region, and the ‘10,000 Lives’ initiative aimed to increase awareness and uptake of these interventions. In this way, the initiative focused on maximising the use of existing services available in the region.

The initial plan of the initiative was guided by the standard principles (described in the Planning part of the results section) of programme implementation. The initiative was officially launched in each of the local government areas of CQ region at a Smoking Cessation Summit. Participation of the people from multiple sectors including health and community services and state and local government in the inaugural summits ultimately facilitated the initiative to build the partnerships and identify champions. Partnerships with various government and non-government organisations opened and enhanced the opportunities to increase the coverage of workplace-based smoking cessation intervention (e.g., smoke-free policies and referrals to Quitline). Partnership with Quitline Queensland assisted the initiative to promote their Intensive Quit Support Programme among the partnering organisations (e.g., hospitals, councils and NGOs). Besides, the regular communication and motivation to the stakeholders (clinical and community champions) helped the SPO to identify the opportunities (e.g., arrange training and workshop on smoking cessation) and tackle the barriers of smoking cessation work for them. For example, if any champion talked about any organisational challenge to perform or promote smoking cessation, the SPO took initiative to escalate the issue to his or her supervisor and discussed to resolve the issue. While not all opportunities and barriers were able to be successfully resolved, a reasonable proportion (~32%) led to successful outcomes (table 5). These integral strategies of building partnerships and communication became useful to build a clinical and a community taskforce of smoking cessation in CQ that leveraged the existing smoking cessation programme and policies available in the region. This approach is an exemplar of running a health promotion campaign in a resource constrained environment.

The ‘10,000 Lives’ initiative was built on the success of a previous health promotion campaign ‘10 000 Steps Rockhampton’ in this region.18 19 The Rockhampton area was chosen for ‘10 000 Steps Rockhampton’ programme because of the high prevalence of obesity.18 Again, ‘10,000 Lives’ initiative was launched in CQ to address the higher prevalence of smoking in this region. The ‘10,000 Lives’ used the programme strategies (e.g., media campaign, partnerships with clinicians and focusing on priority populations) that were also used in the ‘10 000 Steps Rockhampton’ programme.18 Other similarities include the use of technology to measure exhaled carbon monoxide in ‘10,000 Lives’ and pedometers in ‘10 000 Steps Rockhampton’ to measure activity levels. The use of the carbon monoxide breath monitor provided a teaching moment to discuss the health impacts of smoking by demonstrating the person’s exposure to one of the toxins in cigarette smoke, leading to increased autonomous motivation to quit smoking. Creating autonomous motivation in people who smoke, explained by the ‘Self-Determination Theory’,43 is effective for promoting smoking cessation.44

However, the implementation of the programme was sometimes challenging, such as increasing clinician participation in delivering brief smoking cessation advice and Quitline referrals. Some stakeholders expected ‘10,000 Lives’ to directly deliver smoking cessation services. Future programme planning may need to think about how cost-effective and talilored services can be incorporated in the smoking initiative like ‘10,000 Lives’. The ‘10,000 Lives’ initiative is quite different from other smoking cessation programmes in Australia (e.g., B.strong and Quitline) that deliver smoking cessation assistance. Rather, ‘10,000 Lives’ intended to increase motivation to quit, and raise awareness of existing smoking cessation assistance that is available via these other programmes. While the National Tobacco Campaign21 and statewide antismoking campaigns primarily use paid advertisement to disseminate the quit smoking message, the ‘10,000 Lives’ programme focused on low cost and targeted approaches to disseminating the quit smoking message via partnerships with local media and local clinical and community champions for promoting the smoking cessation interventions. This model has also been used in other health promotion programmes implemented in New South Wales, Australia, and in a community of North East England.45 46

The strategies for achieving the goal of the ‘10,000 Lives’ initiative reflect ecological models of health promotion, which explain the multiple levels of influence on health behaviour.47 For example, the initiative put substantial efforts to increase the use of interventions of smoking cessation programmes by involving the service providers in the community (e.g., clinicians and NGO personnel) such this is a ‘downstream’ approach. Again, the ‘10,000 Lives’ initiative encouraged clinicians to deliver brief interventions with their patients and refer them to Quitline and other relevant smoking cessation programmes. The use of local radio, which involved sports stars discussing smoking cessation, and posting messages on Facebook pages are examples of ‘midstream’ strategies, while the advocacy of state-level policies and programmes (e.g., smoke-free hospitals) are ‘upstream’ strategies. Thus, the ‘10,000 Lives’ programme fits the multilevel population based health promotion model of McKinlay.48

The current study had some limitations. Some outputs may have been missed due to lack of documentation of all activities within the project field notes. Reporting the process of a programme through a specific model might limit the information reported; therefore, we used a standard health promotion evaluation framework to increase rigour. Achievements of the ‘10,000 Lives’ programme include the formation of a tobacco control alliance with health professionals, local authorities, communities and the media in CQ, dissemination of knowledge to health professionals on how to deliver brief interventions, distributed promotional material that raised the profile of smoke-free policies and smoking cessation support available in CQ and conducted events and local campaigns to increase awareness of smoking cessation among the general community and specific priority populations. The immediate and short-term impacts of the ‘10,000 Lives’ initiative assessed via a stakeholder survey and analysis of Quitline data will be reported in detail elsewhere. However, we found good responses from the stakeholders in sharing their experience, role and recommendation for the continuation of the initiative. Our analysis of Quitline data indicated a significant positive impact of the introduction of ‘10,000 Lives’ in CQ on referrals, calls and use of Quitline services in comparison with a comparable control group.

Conclusion

The ‘10,000 Lives’ is an example of a health promotion programme that coordinates smoking cessation activities in a regional area by harnessing and improving awareness of existing resources (e.g., employing only one project officer). Using existing resources and programmes can be a cost-effective approach in countries like Australia, where effective smoking cessation interventions are already widely available, but uptake is suboptimal. Evaluation of impact and outcome of this initiative could inform the development of future regional smoking cessation programmes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the unrestricted support from Central Queensland Public Health Unit, Central Queensland Hospital and Health Service, Preventive Health Branch and Quitline Services from Queensland Health (Queensland Government). We would like to thank Caron Williams, the first senior project officer of the '10,000 Lives' programme, and Susie Cameron, the service integration officer of CQ Mental Health Alcohol and Other Drugs Services, for sharing the project information through informal discussions and emails. Also, we would like to thank Linda Medlin, Acting Director of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Wellbeing in Central Queensland Hospital and Health Service for her kind review of the manuscript in the perspective of cultural respectability.

Footnotes

Twitter: @arifkhancvs, @mrsgreeny6

Contributors: AK, GK, SL and CG conceived and designed the study. AK conducted the key informant interviews. AK and KG extracted the data from different sources. AK performed the analysis of the data. All authors interpreted the results. AK drafted the manuscript and all authors contributed with critical revisions to the contents of the manuscript. The final version of the manuscript was approved by all authors.

Funding: The research is funded by the collaborative research grant between School of Public Health at University of Queensland and Central Queensland Public Health Unit, which is awarded by the Central Queensland Hospital and Health Service (CQHHS93907).

Map disclaimer: The depiction of boundaries on this map does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ (or any member of its group) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. This map is provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by CQHHS Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) (HREC/2019/QCQ/50602).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No additional data available.

References

- 1.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Australian burden of disease study 2015: interactive data on risk factor burden, 2019. Available: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/burden-of-disease/interactive-data-risk-factor-burden/contents/tobacco-use [Accessed 17 Jun 2019].

- 2.Data tables: ABDS 2015 risk factors estimates, 2019. Available: https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/28658401-d7f2-4e93-bb6f-9cbd2d5fa64c/ABDS-2015-Risk-factor-data.xlsx.aspx

- 3.Queensland Health . Full 2020 chief health officer report, 2020. Available: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/research-reports/reports/public-health/cho-report/current/full

- 4.Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) . National health survey: first results, 2017-18, cat. No. 4364.0.55.001. Released at 11:30 AM (Canberra time) 07/02/2019, 2018. Available: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/4364.0.55.001~2017-18~Main%20Features~Smoking~85 [Accessed 30 Aug 2019].

- 5.Queensland Health . The health of Queenslanders 2016. Report of the chief health officer Queensland. Queensland Government, 2016. https://www.publications.qld.gov.au//dataset/chief-health-officer-reports [Google Scholar]

- 6.Queensland Government . Central Queensland hospital and health service. 2016, 2019. Available: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/cq [Accessed 1 Jan 2019].

- 7.Queensland Health . Detailed Queensland and regional preventive health survey results. Preventive health surveys, 2019. Available: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/research-reports/population-health/preventive-health-surveys/detailed-data#documentation [Accessed 29 Aug 2019].

- 8.Queensland Regional Profiles . Queensland government, 2019. Available: https://statistics.qgso.qld.gov.au/qld-regional-profiles [Accessed 29 Jul 2019].

- 9.Queensland Health . The health of Queenslanders 2018. Report of the chief health officer Queensland. hospital and health service profiles 2018.

- 10.Australian Government the Department of Health . National tobacco strategy, 2018. Available: https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/tobacco-strategy [Accessed 7 Aug 2019].

- 11.Australian Council on Smoking and Health . National tobacco control Scoreboard, 2019. Available: https://www.acosh.org/what-we-do/national-tobacco-control-scoreboard/ [Accessed 4 Jun 2020].

- 12.Queensland Health . Queensland trends, 2020. Available: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/researchreports/population-health/preventive-health-surveys/data-trends [Accessed 27 Jan 2021].

- 13.Queensland Health . Where quitters click, 2019. Available: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/news-alerts/campaigns/tobacco/where-quitters-click-campaign [Accessed 8 Aug 2019].

- 14.Queensland Health . Smoking prevention strategy 2017 to 2020, 2017. Available: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0022/651802/health-wellbeing-strategic-framework-smoking.pdf [Accessed 4 Jun 2020].

- 15.Central Queensland Hospital and Health Services . Destination 2030, 2017. Available: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0037/669772/destination-2030-full.pdf [Accessed 8 Aug 2019].

- 16.World Health Organization (WHO) . Tobacco, 2019. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tobacco [Accessed 5 Aug 2019].

- 17.Queensland Health . 10000 lives CQ smoking cessation project, 2020. Available: https://clinicalexcellence.qld.gov.au/improvement-exchange/10000-lives-cq-smoking-cessation-project [Accessed 8 May 2020].

- 18.Brown WJ, Eakin E, Mummery K, et al. 10,000 steps Rockhampton: establishing a multi-strategy physical activity promotion project in a community. Health Promot J Aust 2003;14:95–100. 10.1071/HE03095 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wendy JB, Kerry M, Elizabeth E. 10,000 steps Rockhampton: evaluation of a whole community approach to improving population levels of physical activity. J Phys Act Health 2006;3:1–14. 10.1123/jpah.3.1.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson H, Shiell A. Preventive health: how much does Australia spend and is it enough? Canberra, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hill D, Carroll T. Australia's national tobacco campaign. Tob Control 2003;12 Suppl 2:9ii–14. 10.1136/tc.12.suppl_2.ii9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carroll T, Rock B. Generating Quitline calls during Australia's national tobacco campaign: effects of television advertisement execution and programme placement. Tob Control 2003;12 Suppl 2:40ii–4. 10.1136/tc.12.suppl_2.ii40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cotter T, Perez DA, Dessaix AL, et al. Smokers respond to anti-tobacco mass media campaigns in NSW by calling the Quitline. N S W Public Health Bull 2008;19:68–71. 10.1071/NB07098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller CL, Wakefield M, Roberts L. Uptake and effectiveness of the Australian telephone Quitline service in the context of a mass media campaign. Tob Control 2003;12 Suppl 2:53ii–8. 10.1136/tc.12.suppl_2.ii53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kmietowicz Z. Plain tobacco packaging in Australia increases calls to Quitline. BMJ 2014;348:g1646. 10.1136/bmj.g1646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Power J, Grealy C, Rintoul D. Tobacco interventions for Indigenous Australians: a review of current evidence. Health Promot J Austr 2009;20:186–94. 10.1071/HE09186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walker RC, Graham A, Palmer SC, et al. Understanding the experiences, perspectives and values of Indigenous women around smoking cessation in pregnancy: systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Int J Equity Health 2019;18:74. 10.1186/s12939-019-0981-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prevention and Population Health Branch 2010 . Evaluation framework for health promotion and disease prevention programs, Melbourne, Victorian government department of health. Available: https://www2.health.vic.gov.au/about/publications/policiesandguidelines/Evaluation-framework-for-health-promotion-and-disease-prevention-programs [Accessed 10 Dec 2018].

- 29.Boykan R, Messina CR. A comparison of parents of healthy versus sick neonates: is there a difference in readiness and/or success in quitting smoking? Hosp Pediatr 2015;5:619–23. 10.1542/hpeds.2014-0247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lovett R, Thurber KA, Maddox R. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander smoking epidemic: what stage are we at, and what does it mean? Public Health Res Pract 2017;27. 10.17061/phrp2741733. [Epub ahead of print: 11 Oct 2017]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leventhal AM, Bello MS, Galstyan E, et al. Association of cumulative socioeconomic and health-related disadvantage with disparities in smoking prevalence in the United States, 2008 to 2017. JAMA Intern Med 2019;179:777–85. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.QSR International . NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software [Software], 1999. Available: https://qsrinternational.com/nvivo/nvivo-products/

- 33.Central Queensland Hospital and Health Services . Project Plan: 10,000 Lives. In. Rockhampton, Queensland, Australia Central Queensland Public Health Unit; 2017:Page 2 of 16

- 34.Rotary Club . Rotary Districs 9570, central Queensland. Available: https://rotary9570.org/ [Accessed 5 May 2020].

- 35.Headspace . Headspace Rockhampton. Available: https://headspace.org.au/headspace-centres/rockhampton/ [Accessed 5 May 2020].

- 36.Menzies School of Health Research . B.strong; Quit, Eat & Move for Health. Available: https://www.bstrong.org.au/ [Accessed 1 Aug 2019].

- 37.Deadly Choices . Deadly choices. Available: https://deadlychoices.com.au/

- 38.Capricorn enterprise. Available: https://capricornenterprise.com.au/ [Accessed 5 May 2020].

- 39.Cancer Council Queensland . Cancer Council. Available: https://cancerqld.org.au/ [Accessed 5 May 2020].

- 40.De Guzman KR, Snoswell CL, Puljevic C, et al. Evaluating the utility of a smoking cessation clinical pathway tool to promote nicotine prescribing and use among inpatients of a tertiary hospital in Brisbane, Australia. J Smok Cessat 2020;15:214–8. 10.1017/jsc.2020.22 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Queensland Health . Gumma Gundoo Indigenous maternal and infant outreach, 2019. Available: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/cq/services/gumma-gundoo [Accessed 6 May 2020].

- 42.The Australasian Professional Society on Alcohol and other Drugs. NICOTINE ADDICTION & SMOKING CESSATION TRAINING COURSE, 2018. Available: https://www.apsad.org.au/news-a-media/209-nicotine-addiction-smoking-cessation-training-course [Accessed 20/3/2020].

- 43.Deci EL, Ryan RM. Self-determination theory. : Handbook of theories of social psychology. 1. Thousand Oaks: CA: Sage Publications Ltd, 2012: 416–36. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Williams GC, Gagné M, Ryan RM, et al. Facilitating autonomous motivation for smoking cessation. Health Psychol 2002;21:40–50. 10.1037/0278-6133.21.1.40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Campbell MA, Finlay S, Lucas K, et al. Kick the habit: a social marketing campaign by Aboriginal communities in NSW. Aust J Prim Health 2014;20:327–33. 10.1071/PY14037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McGeechan GJ, Woodall D, Anderson L, et al. A coproduction community based approach to reducing smoking prevalence in a local community setting. J Environ Public Health 2016;2016:5386534:4–8. 10.1155/2016/5386534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smedley BD, Syme SL, Committee on Capitalizing on Social Science and Behavioral Research to Improve the Public's Health . Promoting health: intervention strategies from social and behavioral research. Am J Health Promot 2001;15:149–66. 10.4278/0890-1171-15.3.149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McKinlay JB. The promotion of health through planned sociopolitical change: challenges for research and policy. Soc Sci Med 1993;36:109–17. 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90202-F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.