Abstract

Significance.

Uncorrected refractive error is the main cause of visual impairment globally. Understanding barriers and facilitators underserved individuals face in obtaining eyeglasses will help address high rates of uncorrected refractive error.

Purpose.

Understanding the barriers and facilitators to obtaining eyeglasses among low-income patients in Michigan.

Methods.

Participants over 18 years old with hyperopia, myopia, or presbyopia and without active eye disease, severe mental illness or cognitive impairment at Hope Clinic, Ypsilanti, Michigan, United States. The participants answered a sociodemographic survey, underwent autorefraction, and an interview. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and analyzed by two investigators.

Results.

Interviews were completed by 43 participants and 30 participants’ interviews were analyzed. The 30 participants were 55 ± 12 years old, 70% female, 57% African American, 40% had high school diploma or less, 57% earned less than $25,000/year, 93% worn glasses previously, and 87% had some medical insurance. Uncorrected visual acuity was logMAR 0.73 ± 0.61; best corrected visual acuity was logMAR 0.16 ± 0.21. Thematic saturation was reached after 25 transcripts. Top barriers to using eyeglasses were cost (312 mentions, 29 participants), negative experiences with eyeglasses (263, 29), and limited access to eyecare (175, 27). Top facilitators were positive experiences with glasses (230, 29), easy access to eyeglasses (143, 27), and availability of transportation (65, 27). Most participants (97%, 29 participants) reported being negatively impacted by uncorrected refractive error. Most (97%, 29) were skeptical about obtaining eyeglasses online due to possible prescription problems.

Conclusions.

Key barriers to correcting uncorrected refractive error in our community span across multiple health domains but are predominately rooted in external factors such as cost and access to vision care were barriers to obtaining eyeglasses. Online eyeglasses may address access issues, but many participants were uncomfortable or unable to obtain glasses online.

Uncorrected refractive error is the most common cause of visual impairment and the second most common cause of blindness worldwide.1,2 In the United States (US) in 2015, uncorrected refractive error was responsible for visual impairment in 8.24 million people and blindness in 0.29 million people.3 The prevalence of visual impairment and blindness from uncorrected refractive error in the US is expected to double by 2050, driven by increases in myopia and presbyopia.3 The World Health Organization published the Global Action Plan aiming to reduce the prevalence of visual impairment from cataracts and uncorrected refractive error by 25% in 2019 compared to the their prevalence in 2010.4 Instead, in 2017, the prevalence of avoidable visual impairment had increased by 5.6% from their 2010 baseline.1 These trends highlight the urgent need to develop additional strategies to address current and future cases of uncorrected refractive error.3,5,6

Uncorrected refractive error has a profound impact on society and individuals. In 2020, the annual economic cost of uncorrected refractive error per citizen in the US is projected to be about $5,316, more than ten times the average one-time cost of glasses.7 The true economic cost is likely higher, as it decreases workplace productivity,8,9 associated with poverty,10 and decreased mobility.11 On an individual level, visual impairment from uncorrected refractive error negatively impacts health,9 activities of daily living,3,12 quality of life,13 and is associated with cognitive decline.14,15 In contrast, correcting refractive error with eyeglasses increases workplace productivity,8 improves vision-related quality of life,16 promotes mobility,11 and decreases depression.17

Previous studies have identified obstacles to obtaining eyeglasses, including cost,7 limited access to healthcare,18 health literacy,19 and social norms.20 Given the magnitude and impact of uncorrected refractive error, we explored the facilitators and barriers to obtaining eyeglasses among underserved participants in Southeastern Michigan, US. Furthermore, we investigated the attitudes of our participants towards potential solutions like obtaining eyeglasses online.

METHODS

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Michigan and adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were recruited at Hope Clinic in Ypsilanti, Michigan, US from June-August 2017. Hope Clinic is a free clinic that serves any low-income patients who are uninsured and underinsured. Through a partnership with University of Michigan Department of Ophthalmology, Hope offers free comprehensive ophthalmic examinations to their clients once every two months on a Saturday.21

Potential participants were approached in the food bank area of Hope Clinic. Inclusion criteria included age ≥ 18, ability to converse in English, and a history of refractive error (hyperopia, myopia, or presbyopia). Patients with active eye disease, severe mental illness, or cognitive impairment were excluded. Approximately 100 patients were approached. Written informed consent was obtained in English. Participants completed a sociodemographic survey on gender, education, race, ethnicity, income, and insurance status. Mean and standard deviation for the demographic details of our participants were calculated. Refractive data including the sphere, cylinder, uncorrected visual acuity, and best corrected visual acuity were measured using a Nidek ARK-1s autorefractor (Nidek Co LTD, Aichi, Japan).

Participants were interviewed by a single interviewer (LK) using a semi-structured interview guide (see Appendix A, available at [LWW insert link]). The interview guide was designed to elicit key factors that lead people to get or not get eyeglasses. The guide was independently reviewed and vetted by Dr. Joshua Ehlrich, a glaucoma specialist and expert in qualitative studies, to ensure no bias was present. All interviews were conducted in English, audio-recorded, and transcribed verbatim. Two investigators (OJK, JC) read and analyzed the transcripts using a stepwise approach guided by grounded theory (see the exact methodology in Appendix B, available at [LWW insert link]).22–24 Analysis of transcripts were discontinued when thematic saturation, the point at which additional interviews provided no new themes, was reached after reading twenty-five interviews, which was further confirmed when interviews 26 to 30 yielded no new themes. Identified themes and reoccurring concepts were coded into a codebook using Nvivo 12.0 (QRS International Pty Ltd., Victoria, Australia) software. Any discrepancies were first resolved by consensus by the two coders (OJK, JC). Any remaining discrepancies in coding were adjudicated by a third investigator (PANC). Agreement between the two coders was calculated as the percentage of time an excerpt was coded under the same theme. The total number of patients expressing a given theme and the total number of times a given theme has been mentioned was also calculated.

RESULTS

47 participants agreed to participate in a survey. Three declined to participate in semi-structured interviews due to time constraints and one declined due to unwillingness to be recorded. 43 participants completed audio-recorded interviews. New ideas were generated in the first 25 transcripts analyzed. No new ideas were generated from transcripts 26–30. Subsequently, the study team determined that thematic saturation had been reached, so the remaining transcripts were not coded or analyzed. Agreement rate between the two coders averaged 94% or higher across every theme examined.

The mean age of the 30 participants whose interviews were analyzed was 55.5 ± 11.9 years. Twenty-one participants (70%) were female, 17 (57%) were African American, 12 (40%) had a high school diploma or less, 17 (57%) earned less than $25,000/year, 28 (93%) had previously worn glasses, and 26 (87%) were insured. Uncorrected visual acuity was logMAR of 0.73 ± 0.61, and best-corrected visual acuity was logMAR of 0.16 ± 0.21. (Table 1) There were 3 patients with greater than 3 diopters of astigmatism.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and clinical characteristics interviewed participants (n=30).

| Continuous Variable | Mean (SD) | Min, Max |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 55.5 (11.9) | 29, 76 |

| Sphere | −2.05 (4.95) | −21.75, 6.75 |

| Cylinder | 1.34 (1.30) | 0, 7.25 |

| UCVA (logMAR) | 0.73 (0.61) | 0.1, 2 |

| BCVA (logMAR) | 0.16 (0.21) | −0.1, 1 |

| Better-eye BCVA (logMAR) | 0.12 (0.21) | −0.1, 0.6 |

| Categorical Variable | Number (30) | % |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 8 | 26.7 |

| Female | 21 | 70.0 |

| Declined to Answer | 1 | 3.3 |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 8 | 26.7 |

| High school diploma | 4 | 13.2 |

| Some college | 8 | 26.7 |

| College degree | 7 | 23.3 |

| Graduate degree | 3 | 9.9 |

| Race | ||

| White | 6 | 20.0 |

| Black or African American | 17 | 56.7 |

| Native American or Alaska Native | 0 | 0 |

| East Asian | 0 | 0 |

| South Asian | 2 | 6.7 |

| Other | 5 | 16.7 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 2 | 6.7 |

| Non-Hispanic | 21 | 70.0 |

| Declined to Answer | 7 | 23.3 |

| Income | ||

| >$25,000 | 17 | 56.7 |

| $26,000-$50,000 | 5 | 16.7 |

| $51,000-$100,000 | 1 | 3.3 |

| Have insurance? | ||

| Yes | 26 | 86.7 |

| No | 4 | 13.3 |

| Experience Wearing Glasses? | ||

| Yes | 28 | 93.3 |

| No | 1 | 3.3 |

| Declined to Answer | 1 | 3.3 |

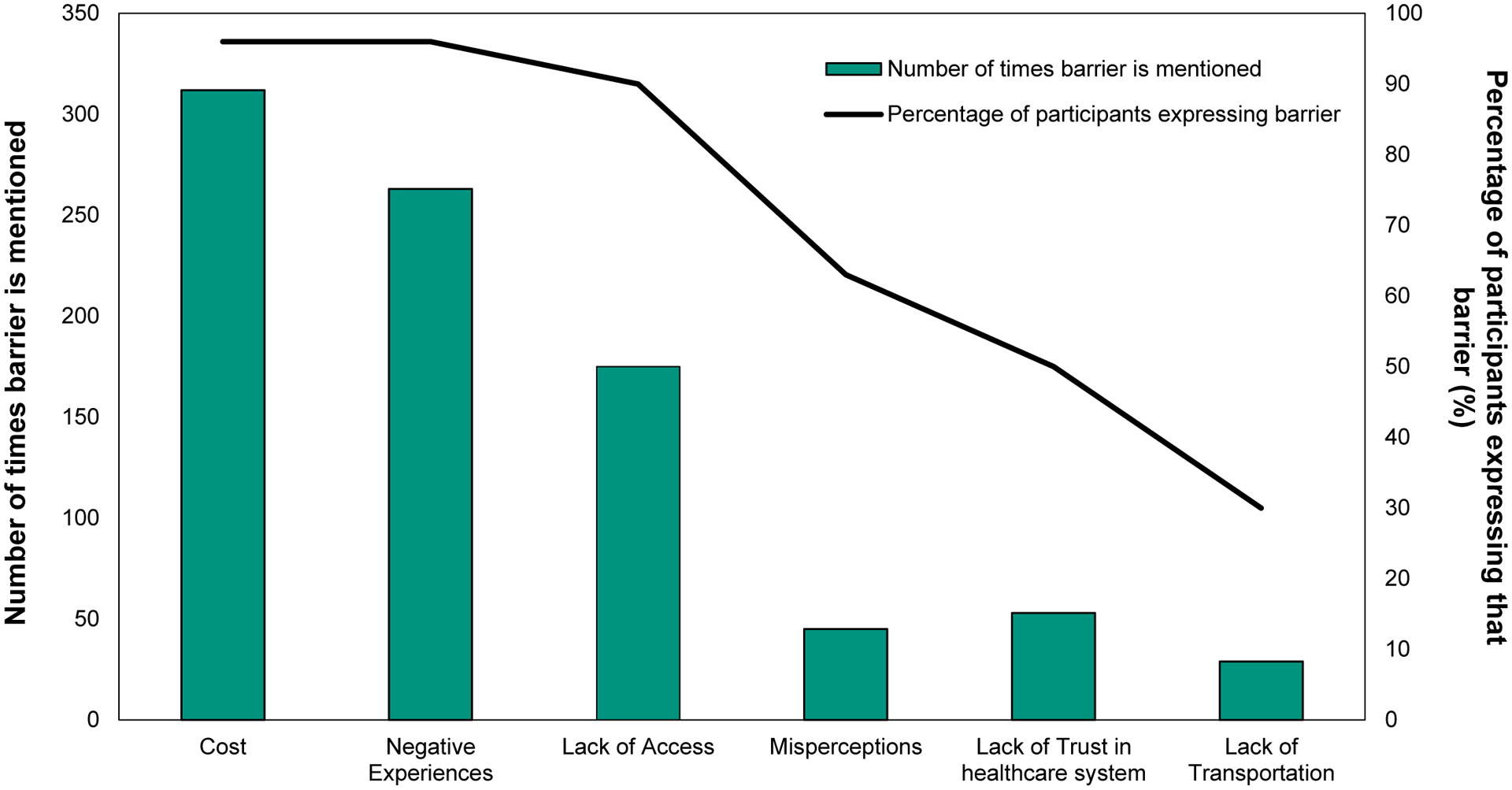

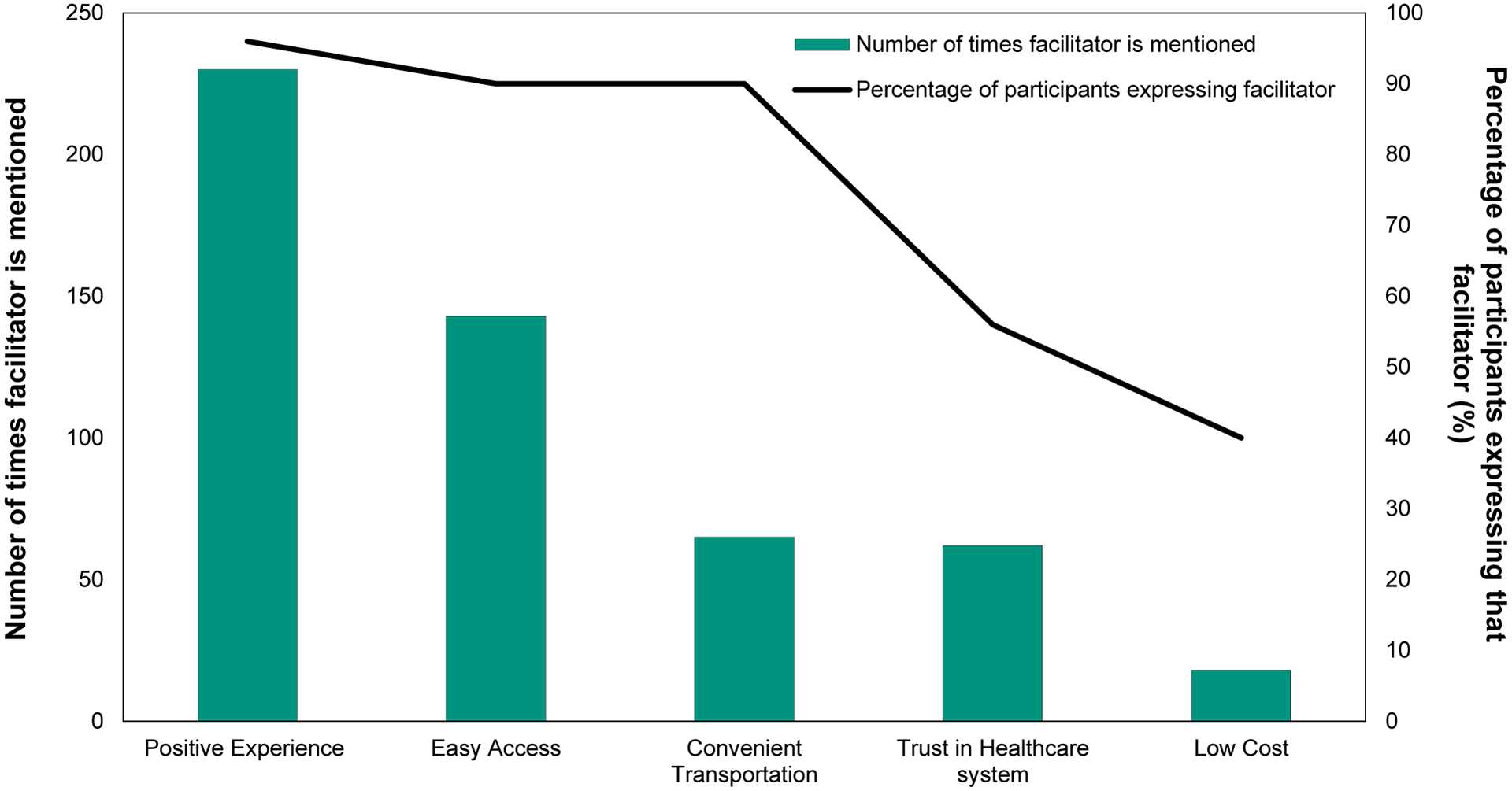

Among the 30 interviews analyzed, the most frequently mentioned barrier to obtaining eyeglasses was cost (312 total mentions, by 29 participants; 96% of participants). Other barriers were negative experiences with eyeglasses (263, 29; 96%), lack of access (175, 27; 90%), misperceptions (45, 19; 63%), lack of trust in healthcare system (53, 15; 50%), and lack of transportation (27, 9; 30%). (Figure 1) The most common facilitator to obtaining eyeglasses was positive experiences with eyeglasses (230, 29; 96%). Other top facilitators were easy access (143, 27; 90%), convenient transportation (65, 27; 90%), trust in healthcare system (62, 17; 56%), and low cost (18, 12; 40%) (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Total number of times a barrier to eyeglass correction is mentioned (bar graph) and percentage of participants expressing each barrier (line graph).

Figure 2.

Total number of times a facilitator to eyeglass correction is mentioned (bar graph) and percentage of participants expressing each facilitator (line graph).

Close examination of statements categorized under the barrier, “cost,” revealed that participants simply could not afford eyeglasses. For example, “Two pairs for $65 with an eye exam. $65 is a lot for somebody that doesn’t have a substantial income…” Patients shared that cost was prohibitive given other financial obligations, for example, “You got more bills. You got to keep a roof over your head. You got to have food to eat and things for your kids and things. The glasses will have to wait.” Patients spoke extensively about negative experiences with glasses, the second most common barrier. They used many adjectives such as “bulky”, “monstrous”, “big”, “ugly”, “problematic”, and “fragile” to describe their glasses. As one participant described, “My glasses are humongous. They’re heavy and they’re not comfortable at all. They’re always falling and they’re just not comfortable. I’m always pushing them up.” While 97% of the interviewed participants described negative experiences with eyeglasses, only three participants (10%) felt negative experiences were significant enough to stop them from wearing their glasses. These three participants made statements like, “the glasses they give me, pop bottle glasses, we won’t wear them,” and “Do I like wearing the ones I have? No. I don’t wear them.” The other 26 participants (87%) shared that negative experiences did not stop them from wearing glasses.

The third most common barrier was lack of access. Lack of access included lack of insurance coverage and difficulty finding eye providers and optical shops that accepted participants’ insurance. For example, “I need a new pair [of glasses] really bad. And I’ve been calling around, calling around […] Trying to find one that will take my combination of insurance because it’s a Medicare with Medicaid backup. So one has to compliment the other, it just won’t take the one or the other.”

The most common facilitator to acquiring glasses was positive experiences with glasses. Participants shared the positive impact glasses had on their daily lives. In one participant’s words, “Wearing glasses affects my life in terms of my overall functionality. I can drive a car, I can walk, I can see, I can recognize people and things. It’s allowed me to become a part of the general public and population.” The next most common facilitators were easy access to glasses and convenient transportation. Some patients reported that vision insurance made it easy to get glasses. As one patient reported, “How easy and hard is it to get glasses? It’s not hard for me because I have insurance.” Others discussed that there were numerous optical shops in their neighborhood, making it easy to obtain glasses. Participants shared that there were several convenient ways to get to eye care providers. For example, “I think if your eyes is bad enough, you’re going to find a way to get to the eye doctor, be it cab, bus, or with Medicaid. Yeah, with Medicaid they have a number that you can call that will get you to whatever appointments you need to be with.”

Patients shared that lack of eyeglasses had profound impacts on their lives, limiting employment, family involvement, safety, and leisure. Some detailed how they lost jobs or struggled at work due to vision problems. In one participant’s words, “I can’t see good enough to do my job.” Participants stated that poor vision limited their ability to enjoy recreation and time with family. For example, “My granddaughter, she’s looking kind of fuzzy […] I think I’m missing a lot.” And “I can’t read for a very long time, I can’t thread a needle.” Several admitted to feeling unsafe on the road or getting in car accidents due to poor vision. As one participant put it, “I got in a car accident. After 6 o’clock I will not drive, because that’s how I got in that accident.” Another stated “I have run somebody off the road on the highway.”

Twenty nine out of the 30 participants (97%) were skeptical about obtaining glasses online. They expressed concerns that the prescription would be inaccurate, the eyeglasses would not fit, and that the process of obtaining glasses online would be difficult or make them vulnerable to online scams. Some participants did not have access to a computer or the internet. In the words of one participant, “I don’t even own a computer. I don’t even know how to use a computer. It might be a scam.” Another stated “I do not know how to go on the internet because I don’t have any laptops or anything like that. I do not know how to operate it. I don’t feel comfortable. Why when you can personally go and meet and attend to it, why the hell do you want to use the computer to buy your glasses?” One participant stated “You need your eyes checked by a specialist to check what state your eyes are in. Not the internet, because the internet can’t examine your eyes.”

Although all but one participant had significant concerns about getting glasses online, some also identified potentially positive aspects of getting glasses online. One reported “If I had the prescription I would probably want to give it a try. I would talk to my daughter first because she’s bought a lot of things online, you know, high-tech devices and what not. So I would trust her judgement about a website because I’m not that great on the internet, but if I had the prescription and it was like a reputable company. I would probably go for it.” Another participant felt that purchasing glasses online would not work for him, but he saw utility for others: “And it just made it ten times easier to get glasses. It’s very helpful. In this day and age, you can get anything online and that I think is very helpful, because some people can’t leave their homes or are bedridden and I think that would be a good idea for them.”

Several participants independently discussed the experience of selecting “ugly”, or “uncomfortable” glasses from a “Medicaid drawer” at the optical shop. For example, “When you go get glasses, they take you off to the corner and these are the only glasses you can get. You are getting the cheapest glasses they got out there, they had on the shelf for years. Who’s going to wear them, who’s going to get them?” Another participant shared the sentiment, “There’s not much of a choice because on Medicaid, they only have like one little drawer of glasses that you can get and a lot of them are ugly. Just that I wished there was more of a selection.”

Two of the three patients with severe astigmatism had negative childhood experiences related to wearing eyeglasses, including being bullied for wearing thick glasses. In the words of one participant, “they used to call me ‘cola lens’ because the glass is so big,” Another stated, “I’ve heard every comment in school, ‘Look at those bug eyeglasses she is wearing’.” Despite their negative childhood experiences, these participants were very grateful for their glasses as adults because glasses allowed them to function in society by working, driving, and caring for children. For instance, one participant mentioned, “I’m so grateful for the fact that glasses correct most of the trouble I have with vision. I mean, it’s wonderful and it’s amazing.”

DISCUSSION

With rates of myopia and presbyopia on the rise, the burden of uncorrected refractive error on our society will continue to increase.1,3,6 In order to reverse this trend, it is important to understand the factors that promote and impede people from obtaining eyeglasses. Among our participants, the primary barriers to acquiring eyeglasses were cost and lack of access to eye care.

The barriers and facilitators identified in our study can be divided into two broad categories: internal and external factors.25 Internal factors refer to facilitators and barriers that stem from participants’ intrinsic motivations and experiences. For example, internal barriers include negative experiences, misperceptions, and lack of trust in the healthcare system; internal facilitators included positive experiences and trust in healthcare system. External factors refer to structural and societal reasons for seeking or not seeking eyeglass correction. External barriers included expense, lack of access, and lack of transportation; external facilitators included easy access, convenient transportation, and low cost. When divided into these two categories, most barriers were external (518 mentions, 59% of total mentions for barrier); however, most facilitators were internal (357 mentions, 63% of total mentions for facilitators). While most participants were intrinsically motivated to get glasses, they were discouraged by the external hurdles within the healthcare system. A study of barriers to healthy eating and exercise found that internal barriers (e.g., willpower and lack of time) were more difficult to overcome than external barriers (e.g., food cost).26 Encouragingly, internal barriers made up a minority of all barriers for our participants. The data suggests that uncorrected refractive error could be effectively addressed through policy solutions to improve access to vision care and decrease the cost of eyeglasses.

Cost was the biggest barrier to obtaining eyeglasses among our participants, consistent with other studies.18,27–29 A survey conducted by Consumer Reports suggested that the median out of pocket price of glasses from an optical shop in the US is $234.30 For reference, in Ypsilanti, Michigan where Hope Clinic is located, the per capita income was $24,562 in 2018 with over 32% of the population living in poverty.31 Our study participants reflect these demographics, as 57% of our participants reported earning less than $25,000 per year. As many of our participants discussed, when a family is struggling to pay for rent and food, spending money on glasses may not be possible. The significance of cost as a barrier to eye care is evidenced by the findings of the RAND health-insurance experiment, a randomized controlled trial which found that requiring low-income participants to make co-payments drastically reduced uptake of vision related services.32 Nevertheless, patients may be able and willing to obtain glasses when they are reasonably priced. This is evidenced by a study in Baltimore that found that although 75% of participants cited cost as a major barrier to vision care, 72% elected to fill a prescription for glasses when they were offered at $40.29

In the US, cost is closely entwined with insurance coverage.33,18 Federal statues explicitly prohibit Medicare from covering expenses for “routine physical checkups, eyeglasses […] or eye examinations for the purpose of prescribing, fitting, or changing eyeglasses, procedures performed (during the course of any eye examination) to determine the refractive state of the eyes.” (42 U.S.C. § 1395y)34 Medicaid often provides some coverage for eyeglasses for adults, but in many US states, the coverage is limited to specific subsets of the population, such as post-operative cataract patients, pregnant women, or long-term nursing residents.18 Under Michigan Medicaid plans, eyeglasses coverage is limited to those who have a medical necessity based on specific diopter criteria or a concurrent complicating medical condition.35 Replacement of eyeglasses or contact lenses is limited to once a year for recipients over age 21 and twice a year for those under age 21.35 Lack of insurance coverage contributes to low uptake of eye care services among uninsured and publicly insured Americans. In a given year, only 42% of Americans without insurance and 55% of those on public health insurance used eye care services when they experienced vision symptoms.28 In contrast, 67% of Americans with private, employment-based insurance sought eye care services when needed. This leads to wide disparities in age-adjusted use of eye care services based on insurance status.28 Lack of access to vision care—which often translated to inadequate insurance coverage—was a major barrier for our participants. Even those with some public insurance coverage for glasses complained that it was difficult to find an optical shop that would accept their specific insurance.

Although nearly all our participants had negative experiences with glasses, only three stated that they did not wear glasses due to negative experiences. How glasses look, or how the wearer is perceived by others, have been found to be barriers to eyeglass use among school-aged children in Mexico,36 Britain,37 and Tanzania.38 However, the impact of cosmesis on adult patients is less clear. In fact, when asked if people who wear glasses get treated differently, one of our participants made the observation that, “They don’t [get treated differently]. Well unless you’re a kid, the kids are always nasty, but teenager to adult they’re not.” As suggested by the quote, negative experiences may not be a prohibitive barrier among adult patients as social dynamics change throughout life. This echoes the experiences of our 3 participants with high cylinder, 2 of whom were bullied for wearing thick glasses as children but grew to appreciate their glasses as adults. Our data suggests that the perceived cost-benefit ratio of wearing glasses changes as a person ages. With time, the perceived cost of using eyeglasses decreases as individuals are less impacted by bullying, and the perceived benefits increase as life responsibility increases. However, a more in-depth study exploring this topic is needed to confirm our observation.

Our participants cited transportation as a facilitator more often than as a barrier. They indicated that there were numerous feasible options available in their community for getting to an eye doctor or optical shop. In contrast, in a prior study of Hope Clinic patients, 35% of patients reported transportation difficulties as the cause for missing ophthalmology appointments. The seeming discrepancy in these results may be explained by easier access to optical shops compared to one specific tertiary care ophthalmology center.21 Studies of different designs yielded differing results regarding physical access to eye care. One study reported that 24% of counties in the US had neither an optometrist or an ophthalmologist,39 while another found that 90% of the Medicare beneficiary population lived 30 minutes or less from an ophthalmologist and 15 minutes or less from an optometrist.40

The economic costs of uncorrected refractive error are profound. In the US, the annual cost of uncorrected refractive error per person is projected to be $5,317. In contrast, the average one-time cost for fitting eyeglasses—including examination, lens, and frames—is estimated to be $397.60. This staggering cost difference means that if everyone with uncorrected refractive error in the US were to be given free eyeglasses, the 10-year savings would amount to more than $87.7 billion.7

To decrease the burden of uncorrected refractive error, we must find ways to make glasses affordable and accessible. One policy solution would be to introduce Medicare coverage and expand Medicaid benefits for glasses, as these would lead to increased eye-care utilization.28 Other, creative solutions should be developed as well. Perhaps there are ways to bring eye care screening and refraction into the primary care setting. For instance, it has been demonstrated that over three fourths of patients with refractive error could be treated by primary care providers with the occasional help of an eye care provider via telemedicine.41 Additionally, online models of eye care could potentially decrease costs and improve access. While there is a lack of published data comparing the price of glasses sold online to those sold in traditional optical shops, a survey conducted by Consumer Reports suggests that the median out of pocket price of glasses was $91 online compared to $234 in store.30

Although the internet can be harnessed to deliver eye care in novel ways, web-based options are not currently designed for low-income populations. Ten percent of all US adults and 27% of adults over 65 do not use the internet.42 Among our participants, all but one had significant concerns about getting glasses online, often related to fears of inaccurate prescription or fit. Having in-person ophthalmic technicians guide patients through the process of obtaining glasses online could assuage patient concerns while harnessing online cost-savings.

This study has notable strengths. Semi-structured interviews gave participants the opportunity to identify their own barriers and facilitators and allowed the interviewer to explore interesting and unique themes in greater depth than a survey would allow. To our knowledge this is also the first study to examine both barriers to and facilitators of eyeglass correction in the US. This study has several limitations. We recruited a convenience sample of participants at one free clinic in Southeast Michigan, so our findings may not be generalizable to the larger population. Although our demographic survey asked whether participants had medical insurance, it did not include follow up questions regarding the type of medical insurance. As a result, we cannot correlate barriers and facilitators to specific types of insurance.

In conclusion, we have found that the key barriers to correcting uncorrected refractive error in our community span across multiple health domains but are predominantly rooted in external factors like the high cost of eyeglasses and limited access to vision care. To tackle uncorrected refractive error, we must implement public policy solutions that address these domains while simultaneously developing new ways of delivering eye care. Potential solutions, such as online methods of obtaining glasses, may work for some, but many patients are wary of online models and prefer in-person experiences. As rates of myopia and presbyopia rise rapidly, innovation in this space is more important than ever.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge Dr. Joshua Ehrlich for helping review and validate our semi-structured interview guide, Swetha Jeganathan for help with data collection, Josh Erickson for help with statistical analysis, and Dr. Jean Cederna for study site and logistical assistance.

Dr. Newman-Casey is supported by the National Eye Institute (Bethesda, MD; K23EY025320, PANC; R01EY031033, MAW). Dr. Woodward is supported by the National Eye Institute (Bethesda, MD; R01EY031033, MAW) and was a consultant for Simple Contacts in 2017.

Appendix A. Semi-structure interview guide and interview items asked.

| Introduction-Motivation: |

| Many Americans struggle to get eyeglasses. We are conducting a study to learn about the barriers to getting eyeglasses, success stories where people have gotten eyeglasses and helped their vision, and people’s thoughts around eyeglasses and wearing eyeglasses. |

|

| Testimonial: |

| Jean knows that she needs because she can’t see to read anymore, but it is hard for her to get eyeglasses. |

|

| Self-efficacy: |

| “I can get glasses if I need them.” |

|

| Social Determinants of health: |

| 1) Sam is not sure he can afford to buy eyeglasses. So, he is not going to get them right now. |

|

| 2) Scenario: A friend of Sam’s got her eyeglasses at a church event. |

|

| 3) Scenario: A friend of Sam’s asked her friend for help to get her eyeglasses. |

|

| 4) Scenario: One of your friends got their eyeglasses on the Internet. |

|

| Access to Care: |

| 1) “I would like to get eyeglasses but it is hard to get to an eye doctor for a glasses prescription.” |

|

| 2) “I would like to get eyeglasses but it is hard to find a place that sells eyeglasses.” |

|

| 3) “I worry that eyeglasses may harm their eyes.” |

|

| Insurance: |

| “Grace waited until she got insurance to get eyeglasses.” |

|

| Competing Priorities: |

| “I know I need eyeglasses but other things are more important to pay for and concentrate on right now.” |

|

| Value of Vision: |

| “It is important to wear eyeglasses if you have trouble seeing things.” |

|

| Personal Health and Vision: |

| Many people have medical problems that they have to deal with and their medical problems cost a lot of time and money. They don’t have time to get eyeglasses. They get by with the vision that they have. |

|

| Motivation: |

| Story: Shelia thought her vision was fine until she mixed up her medicines at home because of the small print on the bottle, and she had trouble seeing her television. |

|

| Attitudes/ Norms: Stigma, peer influence, perceptions |

|

| Safety: |

|

| Cosmesis: |

| 1) “Most affordable eyeglasses make people look ugly.” |

|

| 2) “Most eyeglasses are hard to wear and are always falling and breaking.” |

|

| Technology: |

| Right now, you can buy cheap eyeglasses online. Someday, everyone will be able to get an eyeglass prescription on the Internet. |

|

| Discussion: |

|

| Test results: |

|

Appendix B. Qualitative Analysis Method Guided by Grounded Theory

Grounded theory is an inductive process of generating theories based on qualitative data. Coders typically follow a stepwise approach typical of grounded theory: 1) familiarization, 2) open coding, 3) axial coding, 4) focused coding, and 5) theory building.

In the familiarization stage, three investigators (OJK, JC, PANC) independently read the interview transcripts and became familiar with the context and general interview topics. Coders determined that thematic saturation, the point at which additional interviews provided no new themes, was reached after reading twenty-five interviews, and this was confirmed when interviews 26–30 yielded no new themes. Open coding involved identification of recurring concepts from thirty interviews. Instances of these concepts were identified and subsequently, during axial coding, relationships between these concepts were considered. Twelve core concepts encompassing related themes were identified and discussed during focused coding. Two coders then worked separately to organize sections of all transcripts into these concepts, coming together to resolve inconsistencies in coding and develop sub-categories (OJK, JC). A third investigator (PANC), who is a recognized expert in the field of ophthalmic qualitative research, agreed that no thematic content had been overlooked and adjudicated where inconsistencies could not be resolved between coders. Coders engaged in memo writing throughout all stages, creating written records to track thought processes. The transcripts were coded and analyzed using standard content analysis methods with Nvivo 12.0 (QRS International Pty Ltd., Victoria, Australia) software. Agreement between the two coders was calculated as the percentage of time an excerpt was coded under the same theme. Finally, the team conducted a close reading of the codes, memos, and analysis and see if any new theory or hypothesis were generated from them.

Appendix C. Barriers, Facilitators, and Example Quotes for each Theme.

| Barrier or facilitator | Quote | Number of participants expressing barrier (% of patients expressing barrier) | Number of times referenced |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barriers to eyeglass correction | |||

| Cost | I don’t have cash. Mine are extremely expensive. Each lens is different and each bifocal is different. So that’s four lenses I have to pay for. The last time I bought glasses they were $670. I can’t imagine five years later what they are going to be now. | 29 (97) | 312 |

| Even if I got just the basic frame, the basic frames are like $60, $70. Then the lenses. It’s the lenses that cost—so infuriating. | |||

| I didn’t get [glasses] as often as I needed them because I can’t afford them. | |||

| My insurance helped me pay for the eye doctor but not with the glasses. So I have to pay for them myself. So sometimes I waited [to get glasses]. | |||

| Even at America’s Best: two pairs for $65 with an eye exam. $65 is a lot for somebody that doesn’t have a substantial income to take out at one time, when you say I could pay half on a cable bill or I could eat, or pay the light bill, you know. Glasses are expensive. And it’s hard, but it’s kind of like choosing between eating and seeing. | |||

| You got more bills. You got to keep a roof over your head. You got to have food to eat and things for your kids and things. The glasses will have to wait. Take care of the primary things first. Self-preservation is the law of the land. You got to have a roof over your head you got to have food to eat. You got to put clothes on your kids backs. You got to have some money and then you take care of [glasses]. | |||

| Rent’s coming up again. I can never even set $5 aside, that’s how tight things are. | |||

| When you don’t have very much money, you got to go to what’s important. And sometimes it seems like getting glasses is not as important as paying the rent or the utility, because they wouldn’t put you out on the street if you don’t have glasses, but they will if you don’t pay your utilities. | |||

| Glasses, eating; easy choice. Glasses, paying the utility bills; easy choice. | |||

| I got to raise my daughter. She is four months old. I can forget glasses. I got to make sure she eats. If it comes down to my daughter, that’s who is going to eat, that’s what I’m going to take care of. I would go blind for her. | |||

| I have a lot of health issues. I already pay for a lot of medications. Some things come before glasses. | |||

| Glasses are expensive. And it’s hard, it’s kind of like choosing between eating and seeing. | |||

| Negative experiences | My glasses are humongous. They’re heavy and they’re not comfortable at all. They’re always falling and they’re just not comfortable. I’m always pushing them up. | 29 (97) | 263 |

| [Glasses are] uncomfortable. If it’s just too much pressure on my nose, it gives me a headache. | |||

| It seems like every time I get them, I lose them. | |||

| Most affordable glasses make people look ugly like coke bottles. Because of the frames, big lenses, who wants to wear big lenses like that? | |||

| Several times I got a pair that the arms has broke off of it. | |||

| Lack of access | I am looking into programs such as clinics or churches or other places that might be able to assist [with glasses]. I know there are programs available but their waiting lists are extremely long. | 27 (90) | 175 |

| I need a new pair [of glasses] really bad. And I’ve been calling around, calling around, just starting at the top of the list literally and going down through the phone book. Trying to find one that will take my combination of insurance because it’s a Medicare with Medicaid backup. So one has to compliment the other, it just won’t take the one or the other. For some reason the systems won’t process it. | |||

| Where I live, there’s [an optical shop nearby]. There’s one about two miles from where I live, but they don’t accept my insurance. | |||

| Well, you’ve got certain doctors that won’t take Medicaid, you’ve got certain doctors won’t take Medicare. | |||

| I’ve called my insurance company and they told me that we don’t cover eyeglass wear. And I was like they don’t cover anything at all. They were like we don’t cover eyeglasses or doctor’s visits. | |||

| Misperceptions | It can actually make your vision worse, if you wear the wrong prescription. It’s a muscle weakness of the muscle, that’s why the eyes keep getting worse. | 19 (63) | 45 |

| I haven’t tried to pay for glasses out of pocket, but I don’t think you can. They mostly want insurance. So I haven’t tried that. | |||

| The wrong prescription can do more harm than good. | |||

| Lack of trust in healthcare system | [My primary care physician] says I don’t know where you can go. That’s the story I get from my PCP. They don’t know where to send you. | 15 (50) | 53 |

| I feel comfortable talking to my [primary care doctor]. My eye doctor not so much, he don’t care, he’s there just to do the exam and get a paycheck. | |||

| I understand the whole concept of having to cover the lights in the building. But I think the markup [on glasses] is just extremely high. | |||

| [My eye doctor] is just there to get a check. I mean, he is getting paid, he don’t care. | |||

| I feel we are literally being gouged financially for a medical device, which you need. | |||

| Lack of transportation | Many people don’t have transportation, so how are they going to get there? It’s only certain places you can go, might be halfway down in Detroit somewhere. Who got the money to go down there? | 9 (30) | 29 |

| I don’t have any transportation and I am on that public bus. It takes me two buses and also to get to my doctor’s office. So I have to get on two buses to get there. So that’s probably about an hour. But if I was in a car it took me maybe 15 minutes. | |||

| I’d have to walk or ride a bike [to the eye doctor]. I can’t drive. | |||

| Facilitators to eyeglass correction | |||

| Positive experiences | Well I have glasses and my life has been changed tremendously, I can read and see better so no more squinting. | 29 (97) | 230 |

| [I feel] safer [with glasses] because I could maybe have seen some things in my community, [like] abandoned houses that I didn’t notice before wearing my glasses that need to be taken down or boarded up. | |||

| Honestly, I look sexy with glasses on and my glasses real nice, real nice and I got good taste. | |||

| [People with glasses] are more likely to get a job, the one who can’t see can’t get no job because they can’t do the job [without good vision]. | |||

| Wearing glasses affects my life in terms of my overall functionality. I can drive a car, I can walk, I can see, I can recognize people and things. It’s allowed me to become a part of the general public and population. | |||

| The last place I lived was not a safe environment. When you are not in a safe environment, you need to be able to see around you. And without glasses you won’t be able to see it well. | |||

| Easy access | Walmart sells glasses. A lot of the major chains: Meyers, Walmart, I don’t know if Kroger’s got them. But there’re a lot of places that have little shops in there where you can get glasses. | 27 (90) | 143 |

| The Gift of Sight helped me get [my glasses]. I couldn’t afford them without the Gift of Sight. That’s an organization that helps people get glasses. | |||

| [If I needed glasses] I would go through my case manager through Community Mental Health and let them work for me. Because I have mental issues so my case manager through Community Mental Health takes care of all that stuff for me. | |||

| I get my eye exams with the help of State Insurance, so I’m happy about that. No issues. My insurance takes care of that. | |||

| How easy and hard is it to get glasses? It’s not hard for me because I have insurance. It’s hard for the people that don’t have insurance. | |||

| I can get [glasses] every two years on my insurance, so it’s not hard. | |||

| Convenient transportation | I think if your eyes is bad enough, you’re going to find a way to get to the eye doctor, be it cab, bus, or with Medicaid. Yeah, with Medicaid they have a number that you can call that will get you to whatever appointments you need to be with. | 27 (90) | 65 |

| Ask someone for a ride. Everybody knows somebody who has a vehicle. And there’s always the bus system. | |||

| I have transportation [to go to the eye doctor]. I have transportation to get there, and if my transportation is bad I call a family member to come take me. | |||

| Trust in healthcare system | I have had no [problems getting glasses]. I guess I have a good team of doctors around me making sure everything is easy for me. My doctor is very cooperative and she checked my eyes very carefully. | 17 (56) | 62 |

| It depends on where you go because some [clinics], you walk in and it is like, the people look and say like “what are you doing here, this is not for you.” And some places when you walk in they are happy and they treat you like you’re family, they greet you and they will make sure you are well taken care of. So it depends on where you go. | |||

| Low cost | At Eyeglass World, $69.99, you get two pair of eyeglasses and your eye exam is free. I think anybody can come up with $70 to go up here and take care of that. | 12 (40) | 18 |

| Nowadays you can get a fairly cheap pair of glasses. Unless you just wanna be fashionable. | |||

| I think it is the website of zenny.com. These are what is called designer eye glasses for like $6.99, $9.89. You just put the number in the way you wear the eye glasses and then they ship it to you. If everybody was informed about that, then it will be helpful for people who didn’t have any money. | |||

REFERENCES

- 1.Flaxman SR, Bourne RRA, Resnikoff S, et al. Global Causes of Blindness and Distance Vision Impairment 1990–2020: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2017;5:e1221–e34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naidoo KS, Leasher J, Bourne RR, et al. Global Vision Impairment and Blindness Due to Uncorrected Refractive Error, 1990–2010. Optom Vis Sci 2016;93:227–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Varma R, Vajaranant TS, Burkemper B, et al. Visual Impairment and Blindness in Adults in the United States: Demographic and Geographic Variations From 2015 to 2050. JAMA Ophthalmol 2016;134:802–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization (WHO). Draft action plan for the prevention of avoidable blindness and visual impairment 2014–2019: universal eye health: a global action plan 2014–2019: report by the Secretariat; EB132/9; 2013. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/78620. Accessed June 11, 2020.

- 5.Holden BA, Fricke TR, Wilson DA, et al. Global Prevalence of Myopia and High Myopia and Temporal Trends from 2000 through 2050. Ophthalmology 2016;123:1036–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holden BA, Fricke TR, Ho SM, et al. Global Vision Impairment Due to Uncorrected Presbyopia. Arch Ophthalmol 2008;126:1731–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wittenborn J, Rein D. The Preventable Burden of Untreated Eye Disorders. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2016. Available at: https://www.nap.edu/resource/23471/UndiagnosedEyeDisorders.CommissionedPaper.pdf. Accessed June 11, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reddy PA, Congdon N, MacKenzie G, et al. Effect of Providing Near Glasses on Productivity Among Rural Indian Tea Workers with Presbyopia (PROSPER): A Randomised Trial. Lancet Glob Health 2018;6:e1019–e27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lou L, Yao C, Jin Y, et al. Global Patterns in Health Burden of Uncorrected Refractive Error. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2016;57:6271–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tafida A, Kyari F, Abdull MM, et al. Poverty and Blindness in Nigeria: Results from the National Survey of Blindness and Visual Impairment. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2015;22:333–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fenwick EK, Ong PG, Man RE, et al. Association of Vision Impairment and Major Eye Diseases With Mobility and Independence in a Chinese Population. JAMA Ophthalmol 2016;134:1087–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zebardast N, Friedman DS, Vitale S. The Prevalence and Demographic Associations of Presenting Near-Vision Impairment Among Adults Living in the United States. Am J Ophthalmol 2017;174:134–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chou R, Dana T, Bougatsos C, et al. Screening for Impaired Visual Acuity in Older Adults: Updated Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2016;315:915–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hajek A, Brettschneider C, Luhmann D, et al. Effect of Visual Impairment on Physical and Cognitive Function in Old Age: Findings of a Population-Based Prospective Cohort Study in Germany. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016;64:2311–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnes SS, Sewell DD. The Value and Underutilization of Simple Reading Glasses in Geropsychiatry Inpatient Settings. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2014;29:657–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McClure TM, Choi D, Wooten K, et al. The Impact of Eyeglasses on Vision-Related Quality of Life in American Indian/Alaska Natives. Am J Ophthalmol 2011;151:175–82.e172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Owsley C, McGwin G Jr, Scilley K, et al. Effect of Refractive Error Correction on Health-Related Quality of Life and Depression in Older Nursing Home Residents. Arch Ophthalmol 2007;125:1471–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Committee on Public Health Approaches to Reduce Vision Impairment and Promote Eye Health. Making Eye Health a Population Health Imperative: Vision for Tomorrow. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2016. Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK385157/. Accessed June 11, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thompson S, Naidoo K, Gonzalez-Alvarez C, et al. Barriers to Use of Refractive Services in Mozambique. Optom Vis Sci 2015;92:59–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schneider J, Leeder SR, Gopinath B, et al. Frequency, Course, and Impact of Correctable Visual Impairment (Uncorrected Refractive Error). Surv Ophthalmol 2010;55:539–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woodward MA, Jeganathan VS, Guo W, et al. Barriers to Attending Eye Appointments among Underserved Adults. J Ophthalmic Vis Res 2017;12:449–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chapman AL, Hadfield M, Chapman CJ. Qualitative Research in Healthcare: An Introduction to Grounded Theory Using Thematic Analysis. J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2015;45:201–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bryant A, Charmaz K The SAGE Handbook of Current Developments in Grounded Theory. London: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2019. Available at: https://methods.sagepub.com/book/the-sage-handbook-of-grounded-theory-2e. Accessed February 16, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foley G, Timonen V. Using Grounded Theory Method to Capture and Analyze Health Care Experiences. Health Serv Res. 2015;50:1195–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cole GE, Holtgrave DR, Rios NM. Systematic Development of Trans-Theoretically Based Behavioral Risk Management Programs. Risk 1993;4:67. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ziebland S, Thorogood M, Yudkin P, et al. Lack of Willpower or Lack of Wherewithal? “Internal” and “External” Barriers to Changing Diet and Exercise in a Three Year Follow-Up of Participants in a Health Check. Soc Sci Med 1998;46:461–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elam AR, Lee PP. Barriers to and Suggestions on Improving Utilization of Eye Care in High-Risk Individuals: Focus Group Results. Int Sch Res Notices 2014;2014:527831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang X, Lee PP, Thompson TJ, et al. Health Insurance Coverage and Use of Eye Care Services. Arch Ophthalmol 2008;126:1121–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quigley HA, Park CK, Tracey PA, Pollack IP. Community Screening for Eye Disease by Laypersons: The Hoffberger program. Am J Ophthalmol 2002;133:386–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Consumer Reports. Eyeglass & Contact Lens Store Buying Guide; 2020. Updated January 31, 2020. Available at https://www.consumerreports.org/cro/eyeglass-contact-lens-stores/buying-guide/index.htm. Accessed February 16, 2020.

- 31.U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Ypsilanti city, Michigan. United States Census Bureau; 2014. Updated December 30, 2020. Available at: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/ypsilanticitymichigan. Accessed February 16, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lohr KN, Brook RH, Kamberg CJ, et al. Use of Medical Care in the Rand Health Insurance Experiment: Diagnosis- and Service-specific Analyses in a Randomized Controlled Trial. Med Care 1986;24:S1–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jeganathan VS, Robin AL, Woodward MA. Refractive Error in Underserved Adults: Causes and Potential Solutions. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2017;28:299–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.U. S. Code of Federal Regulations: §1395y. Exclusions from coverage and medicare as secondary payer; 2019. Available at: https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=(title:42%20section:1395y%20edition:prelim. Accessed June 11, 2020.

- 35.Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS). Medicaid State Plan; 2020. Available at: http://www.mdch.state.mi.us/dch-medicaid/manuals/MichiganStatePlan/MichiganStatePlan.pdf. Accessed September 14, 2020.

- 36.Castanon Holguin AM, Congdon N, Patel N, et al. Factors Associated with Spectacle-wear Compliance in School-aged Mexican Children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2006;47:925–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Horwood AM. Compliance with First Time Spectacle Wear in Children under Eight Years of Age. Eye 1998;12:173–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Odedra N, Wedner SH, Shigongo ZS, et al. Barriers to Spectacle Use in Tanzanian Secondary School Students. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2008;15:410–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gibson DM. The Geographic Distribution of Eye Care Providers in the United States: Implications for a National Strategy to Improve Vision Health. Prev Med 2015;73:30–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee CS, Morris A, Van Gelder RN, Lee AY. Evaluating Access to Eye Care in the Contiguous United States by Calculated Driving Time in the United States Medicare Population. Ophthalmology 2016;123:2456–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lutz de Araujo A, Moreira TdC, Varvaki Rados DR, et al. The Use of Telemedicine to Support Brazilian Primary Care Physicians in Managing Eye Conditions: The TeleOftalmo Project. PLoS ONE 2020;15:e0231034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anderson M, Perrin A, Jiang J, Kumar M. 10% of Americans don’t use the internet. Who are they?. 2019. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/04/22/some-americans-dont-use-the-internet-who-are-they/. Accessed February 16, 2020.