Abstract

Context

The coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) has profoundly impacted the provision of pediatric palliative care (PPC) interventions including goals of care discussions, symptom management, and end-of-life care.

Objective

Gaining understanding of the professional and personal experiences of PPC providers on a global scale during COVID-19 is essential to improve clinical practices in an ongoing pandemic.

Methods

The Palliative Assessment of Needed DEvelopments & Modifications In the Era of Coronavirus Survey-Global survey was designed and distributed to assess changes in PPC practices resulting from COVID-19. Quantitative and qualitative data were captured through the survey.

Results

One hundred and fifty-six providers were included in the final analysis with 59 countries and six continents represented (31% from lower- or lower middle-income countries). Nearly half of PPC providers (40%) reported programmatic economic insecurity or employment loss. Use of technology influenced communication processes for nearly all participants (91%), yet most PPC providers (72%) reported receiving no formal training in use of technological interfaces. Respondents described distress around challenges in provision of comfort at the end of life and witnessing patients’ pain, fear, and isolation.

Conclusions

PPC clinicians from around the world experienced challenges related to COVID-19. Technology was perceived as both helpful and a hinderance to high quality communication. The pandemic's financial impact translated into concerns about programmatic sustainability and job insecurity. Opportunities exist to apply these important experiential lessons learned to improve and sustain care for future patients, families, and interdisciplinary teams.

Article Summary

This original article describes the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on pediatric palliative care clinicians from 59 countries including financial losses, use of virtual communication modalities, and the respondents’ distress in provision of comfort at the end of life.

Key Words: Pediatric palliative care, global, COVID-19

Abbreviations

- COVID-19:

coronavirus pandemic;

- SARS-CoV-2:

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2;

- PPC:

pediatric palliative care;

- PANDEMIC-Global:

The Palliative Assessment of Needed DEvelopments & Modifications In the Era of Coronavirus Survey-Global study;

- LLMIC:

lower and lower middle-income countries;

- UMIC:

upper middle-income countries;

- HIC:

high income countries

Introduction

The current coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has resulted in an unprecedented impact on pediatric patients, families, and healthcare systems around the world.1, 2, 3 As medical teams continue to learn more about the clinical effects of SARS-CoV-2 on children, the literature increasingly suggests that children are not immune to SARS-CoV-2,4 can transmit the disease to others,5 and may become severely ill and even die.6, 7, 8 The disruption in healthcare system delivery is likely to have a profound impact on child health, with an additional 1.2 million children around the world predicted to die due to decreased access to medical care.9

Pediatric Palliative Care (PPC) clinicians have mobilized expeditiously in response to the pandemic in an effort to find creative solutions to continue providing high-quality care for children and their families.10, 11, 12 In the setting of a pandemic, interventions such as conversations about goals of care and advance care planning,13 symptom management, and end-of-life care become more challenging.14 PPC teams must find innovative tools, technologies, and communication modalities to support optimal care provision while ensuring appropriate physical distancing.15 , 16

Recent efforts by our team have assessed the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on palliative care clinicians within the United States.17 , 18 however, the experiences and resources of PPC clinicians outside of the Unites States are unique and poorly understood in the context of the pandemic. A 2011 systematic review showed that 65.6% (n = 126) of countries had no PPC services available, 18.8% (n = 36) had capacity building activities, and only 5.7% had activities that reached mainstream providers (n = 11).19 However, efforts over the last decade have been made to improve PPC globally through increased access to essential medicines, policy measures, and educational initiatives.20, 21, 22, 23, 24 As COVID-19 continues to spread globally, better understanding of the professional and personal experiences of PPC providers around the world is necessary to identify needs and to inform solidarity in clinical practices.

The Palliative Assessment of Needed DEvelopments & Modifications In the Era of Coronavirus Survey-Global (PANDEMIC-Global) study was designed to assess the perceived changes in PPC team functionality, care interventions, and daily challenges resulting from COVID-19. This study aimed to describe the PPC clinician experiences and reflections during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

The Office of Human Subjects Research Protections and Institutional Review Board at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital (Memphis, TN, USA) approved this study as exempt research in the context of targeted population and study design.

Survey Development and Measures

Survey questions were designed by a collaborative, interdisciplinary study team according to the Tailored Method of Survey Design.25 The initial survey was designed for distribution to PPC clinicians across the United States;17 , 18 and due to unique practice settings and resources the survey subsequently underwent significant reworking by an interdisciplinary team of PPC and global clinicians and researchers, with the goal of targeting international PPC participants. Specifically, the survey was independently reviewed for content validity, piloted, revised, and re-piloted by a six-member interdisciplinary team representing four continents. The final survey instrument [Appendix I] consisted of 41 multiple choice and free-text questions implemented in Qualtrics©. Other elements included in the survey including evaluation of changes in end-of-life practices were not included in this manuscript.

Study Population, Recruitment, and Survey Distribution

Palliative care interdisciplinary team members were invited to participate in this anonymous survey. The study team utilized a convenience sampling approach to recruit global PPC providers by sharing the survey link across several global listservs of pediatric palliative care providers including: 1) St. Jude Global Pediatric Palliative Care/Quality of Life Transversal Working Group; 2) International Society of Pediatric Oncology-Pediatric Oncology in Developing Countries Palliative Care Working Group; 3) International Children's Palliative Care Network; 4) European Association of Palliative Care; 5) A Network for Accessible, Sustainable and Collaborative Research in Pediatric Palliative Care; 6) Fondazione Maruzza; and 7) International Association of Hospice and Palliative Care. Each listserv posted one announcement with one follow-up reminder spaced between 7 to 14 days after initial announcement during the dates of June 22 through August 21, 2020. The secure survey link remained open for 9 weeks to maximize data collection.

Analyses

Quantitative and qualitative data were captured as part of the survey. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize quantitative data. Missing data were excluded when calculating frequencies and percentages. Comparison of percentages between groups used the Chi-square or Fisher's Exact test. The data were also summarized by world region and World Bank income status. National indicators were obtained from the World Bank Open Data platform and used to define country characteristics.26 Due to the small number of low-income countries as defined by World Bank Criteria, participants from low-income countries and lower middle-income countries were grouped together. The statistical level of significance was set to 0.05 for all analyses. R Version 4.0.0 (http://www.r-project.org) was used for all summaries and analyses.

Descriptive content analyses were conducted on free-text narrative responses due to the concise nature of typed responses. Free-text responses were analyzed according to open-text questions: something you wish you knew prior to COVID, something you learned during COVID, and description of an impactful COVID experience. Responses were organized according to the presence of words which were then grouped into higher-level themes per open-ended question. One author organized each free-text response into high-level themes with two additional authors checking for consistency in grouping. Disagreements were notably low (<5% responses) with team discussion and consensus for resolution. Themes were tallied to report counts.

Results

Demographics

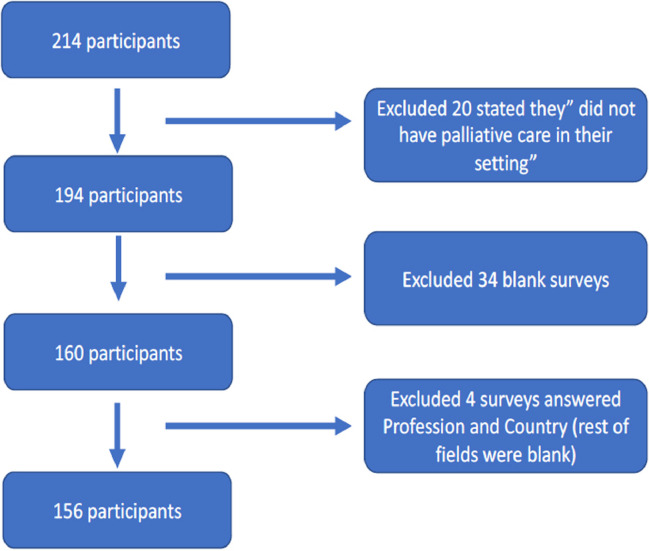

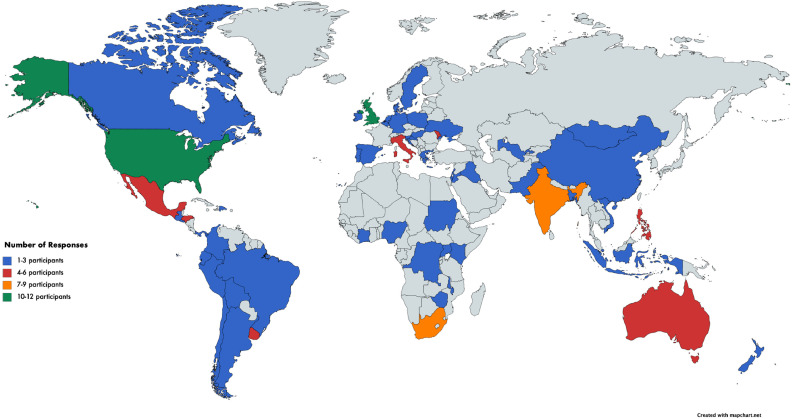

One hundred and fifty-six providers were included in the final analysis Fig. 1. Participant demographic are presented in detail in Table 1 . The majority of survey participants were physicians (59%). Other common disciplines represented included nurses (14%), advanced practice providers (i.e., nurse practitioners or physician assistants) (10%), social work/counselors (4%), and psychologists (3%). Fifty-nine countries and six continents were represented in the sample with a mean of three completed surveys per country Fig. 2. Thirty one percent of participants resided in lower and lower middle-income countries (LLMIC). More than half practiced in a full-time PPC setting (58%).

Fig. 1.

Legend: Presentation of respondent flowchart, including participant exclusion, and final number of participants.

Table 1.

Survey Participants Demographics

| Profession | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Physician | 92 (58.97) |

| Nurse Practitioner/Physician Assistant/Advance Practice Provider | 15 (9.62) |

| Nurse/Nurse case manager | 22 (14.1) |

| Psychologist | 5 (3.21) |

| Child Life Therapist/Play Specialist | 4 (2.56) |

| Pharmacist | 3 (1.92) |

| Charity/Program Coordinator | 3 (1.92) |

| Social Work/Counselor | 6 (3.85) |

| Other | 6 (3.85) |

| Palliative care model | |

| Full-time practicing pediatric palliative care | 91 (58.33) |

| Part-time practicing pediatric palliative care | 65 (41.67) |

| Income Group | |

| Low income & Lower middle income | 48 (30.77) |

| Upper middle income | 39 (25) |

| High income | 69 (44.23) |

| Region | |

| East Asia & Pacific | 20 (12.82) |

| Europe & Central Asia | 44 (28.21) |

| Latin America & Caribbean | 36 (23.08) |

| Middle East & North Africa | 7 (4.49) |

| North America | 14 (8.97) |

| South Asia | 13 (8.33) |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 22 (14.1) |

| Total | 156 (100) |

*Other: Medical Volunteer, Integrative Therapist, General Support, Physiotherapist, Spiritual Support, General Palliative Care

Fig. 2.

Legend: Countries represented by participants. Colors denote number of respondents per country. Blue is 1-3 participants, Red is 5-6 participants, Orange is 7-9 participants, and Green is 10-12 participants.

Practice Environment

Seventy-six percent of the respondents reported that fewer than 20% of their patients were positive for COVID-19, while 20% stated the prevalence of COVID-19 was unknown at the time due to lack of testing. LLMIC were less likely to know positivity rate due to inability to test (56%) as compared to upper middle-income countries (UMIC) (6%) and high-income countries (HIC) (6%) (P-value < 0.001). Forty-nine percent of respondents stated that the daily census had decreased since the start of the pandemic, while 16% felt that the census was unchanged, but the overall number of patient visits had decreased.

Impact on Palliative Care Team

During the pandemic, the majority of physicians (61%), advanced practice providers (61%), and nurses (59%) remained in their usual work locale Table 2 . However, 33% of doctors were working from home part of the time or all the time compared to 26% of advanced practice providers and 25% of nurses. Other multidisciplinary members were either not available at the practice site or working from home Table 2.

Table 2.

Physical Presence of Pediatric Palliative Care Team

| Palliative care Team | Remain in usual work locale | Working from home all of the time | Working from home sometimes | Not working | Not available for palliative care at our site | I don't know | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Physicians | 63 (60.58) | 8 (7.69) | 26 (25) | 0 (0) | 4 (3.85) | 3 (2.88) | 104 |

| Nurse Practitioners/Advanced Practice Providers | 59 (60.82) | 5 (5.15) | 20 (20.62) | 2 (2.06) | 8 (8.25) | 3 (3.09) | 97 |

| Nurses/Nurse Case Managers | 58 (58.58) | 3 (3.03) | 22 (22.22) | 1 (1.01) | 10 (10.10) | 5 (5.05) | 99 |

| Social workers | 32 (32) | 14 (14) | 35 (35) | 5 (5) | 10 (10) | 4 (4) | 100 |

| Chaplains | 18 (18.56) | 7 (7.22) | 18 (18.56) | 7 (7.22) | 31 (31.96) | 16 (16.49) | 97 |

| Integrative therapists | 12 (12.77) | 4 (4.26) | 11 (11.70) | 8 (8.51) | 43 (45.74) | 16 (17.02) | 94 |

| Bereavement coordinators | 18 (19.15) | 6 (6.38) | 17 (18.09) | 3 (3.19) | 37 (39.36) | 13 (13.83) | 94 |

| Child life specialists | 14 (14.58) | 5 (5.21) | 9 (9.38) | 6 (6.25) | 44 (45.83) | 18 (18.75) | 96 |

| Psychologists | 26 (26.53) | 10 (10.20) | 29 (29.59) | 1 (1.02) | 21 (21.43) | 11 (11.22) | 98 |

In addition, 37% of the respondents described changes in the palliative care team due to COVID-19 exposures in a family member or the team member themselves. Those with COVID-19 infection or exposure contributed to burdens on coworkers resulting in less staff available for patient care. One participant reported, “My team is small and if any member is in quarantine, we have a big problem.” No statistically significant differences were observed between country regions or income levels and changes in PPC teams.

Teams Feeling Closer

Fifteen percent of participants reported that the team had grown closer during the pandemic. Of those that reported an increased sense of team cohesion, 29% attributed it to a common mission during the pandemic. Another 21% described an increased value of interdisciplinary roles and 21% discussed the deliberate connection required during the pandemic. Five respondents described the co-existence of increased team cohesion and feeling distanced. This phenomenon was attributed to differences in working remotely versus in-person. One participant wrote, “Sometimes we feel a greater distance with some members of the team because they may have to take care of their health or their families and they cannot attend to the team's queries. However, in most cases we feel virtual closeness to discuss what happens with patients and see how we are doing.”

Teams Feeling More Distant

Conversely, 42% percent of participants described the team as feeling “more distant.” Of those who felt more distant, 47% attributed a sense of disconnectedness to the increased reliance on virtual interfaces. They emphasized the relational, social, or emotional gaps that exist in virtual communication. Another 35% felt increasingly distanced from their colleagues due to decreased frequency of team communication.

Financial Impact

Financial losses also impacted clinicians, with 40% of respondents reporting that either they or their team members experienced salary cuts, furlough, or loss of employment. Reported income losses among palliative care team members ranged from 15% to 100% of their salaries. Two participants described other losses including spousal unemployment due to COVID-19, and another reported that colleagues were no longer working due to challenges in finding childcare. Two participants reported that they were working on a volunteer basis without any financial support. No statistically significant differences in income cuts or job losses were seen by comparing country region or income status.

Patient-Provider Interactions

PPC clinicians reported pandemic-related changes in their communication approaches and content with patients and families. In particular, technology influenced communication changes with 74% of participants stating that they used some sort of technology prior to COVID-19, compared to 91% during the pandemic Table 3 . Employed technologies included Facebook messenger, Zoom, Microsoft Teams, WebEx, Skype, WhatsApp, and telephone calls or SMS text messaging. HIC countries were more likely to use technology with video capabilities (51%) compared to UMIC (38%) and LLMIC (23%) (P-value 0.008). For those using technologies, 72% reported no formal training in the use of these interfaces.

Table 3.

Communication

| Changes to communication with patients/families | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Communications have become more frank | 10 (11.11) |

| Communication has become more decisional | 24 (26.67) |

| Fewer extended relatives are present | 48 (53.33) |

| No Change | 19 (21.11) |

| Less in-person interaction | 7 (7.11) |

| Other* | 2 (2.22) |

| Total | 90 |

| Different technologies to facilitate communication before COVID-19 | |

| Yes | 69 (74.19) |

| No | 24 (25.81) |

| Total | 93 (100) |

| Different technologies to facilitate communication during COVID-19 | |

| Yes | 84 (91.30) |

| No | 8 (8.70) |

| Total | 92 (100) |

| Did your team receive training in the use of the communication technologies | |

| Yes | 25 (28.09) |

| No | 64 (71.91) |

| Total | 89 (100) |

*Other: One respondent stated that there were less palliative care patients in conversations; Another respondent stated that both personnel and families were more isolated

Communication Enhanced by Technology

Eighty participants (51%) responded to the open-ended question asking how communication has been enhanced by technology. Nearly a third (30%) described how technology facilitated consistent access and continued contact with patients and families when they could not be seen regularly in person. Others (10%) described technology as a mechanism to make the encounter easier and more efficient for both clinicians and patients/families. Some PPC clinicians (19%) described the benefit from reduction in travel for patients and families, especially those who live at a distance from the hospital or clinic. Other respondents (14%) stated that technological interfaces were better than no communication at all during the pandemic but remained inferior to in-person communication.

Communication Diminished by Technology

Seventy-four participants (47%) responded to the open-ended question asking how communication has been diminished by technology. More than half (55%) described the lack of personal interaction, physical touch, and empathic expressions of support (e.g., a handshake or a hug for patients and families during this difficult time). Additionally, some (12%) respondents described the inability to assess nonverbal aspects of communication through technology. Others (8%) described challenges related to poor audio/visual quality, poor cell/internet service, as well as the expense. One provider expressed concern that a constant demand for virtual communication may increase risk for burnout. Another provider summarized the overall feeling that, while helpful, technology remains insufficient to support certain conversations in palliative care: “As good as the technology is, nothing can replace the human aspect of being in a room together and being able to provide comfort and support with appropriate and respectful touch.”

Lessons Learned from COVID-19

Findings of the open-ended questions with regards to learning experiences from COVID-19 are found in Table 4 . We asked clinicians what they wish they had known prior to COVID-19 related to their PPC practice, and the most common response (35%) centered on proficiency with virtual communication modalities. In particular, clinicians self-perceived deficits in their effective use of telehealth to communicate and address medical and emotional aspects of PPC. In addition, participants described having a deeper understanding of the challenges inherent to isolation and absence and greater hope that people would be supportive, patient, and understanding.

Table 4.

Lessons Learned From COVID-19

| 1. What is something you wished you knew/learned prior to the COVID-19 pandemic that might have impacted how you approached palliative care during the pandemic? | |

| Remote Communication and Mobility Opportunities | “We were caught unprepared. Would have loved to learn more on virtual support and monitoring” |

| Logistical improvements in infection control, hospital systems, and integration of PPC | “How to respond to public health emergencies/pandemic and manage our system in the hospital vis-a-vis the institutional policies.” |

| Challenges associated with isolation and absence | “I used to touch patient during communication…it is sad not to do now.” |

| 2. What is something you have learned since COVID-19 that will impact your palliative practice going forward? | |

| Use of technology to facilitate communication | “…communication is possible through many means (phone, messaging, etc) Liaisons have become easier for me, maybe because I am doing it more during the pandemic” |

| Importance of access to quality PPC | “The pandemic such as COVID 19 can change the way how we provide quality care to our patients. For physicians who are adamant about palliative care, the COVID highlighted the need to incorporate palliative care services in the care of patients with life-threatening diseases including COVID 19.” |

| Value of Communication | “The importance of other communication channels and overcoming the distances that may exist” |

| 3. Can you tell us about an experience you have had related to COVID-19 that you feel will stay with you, always? | |

| Adapting to new/difficult circumstances and gaining new skills | “The pandemic has changed my way of thinking and has brought out my skill as a nurse in not only managing physical issues but my ability to support and care for our children, their families and our care team and their families from an emotional point of view - which has been hugely challenging” |

| COVID-19 and its impact on end-of-life care | “I never will forget the burden for parents knowing that their child is dying not just because of cancer but because of COVID, being apart from the family, feeling alone including time to be buried without anybody present.” |

| Inability to provide comfort to patients and families at the end-of-life | “The added layers of complexity and difficulty associated with physical distancing stipulations and witnessing the further heartache in not being able to bring loved ones together to mourn the death of a child.” |

| Fear of the unknown | “Most health personnel were afraid of dealing with something unknown, and possibly fatal.” |

When asked about how their pandemic experience will impact their clinical practice moving forward, the most common response (25%) was that PPC clinicians plan to continue utilizing technology to facilitate virtual meetings and patient care in the post-pandemic period. Another common response (19%) centered on lessons learned to improve workplace flow, including streamlining administrative responsibilities and tasks to enhance quality and access to PPC for patients. Respondents (14%) also described the importance of communication within teams and with patients and families.

Finally, when asked about an experience related to COVID-19 that will remain with them always, the most common response focused on learning to adapt to new and difficult circumstances (16%). Specifically, clinicians described new ways of meeting and teambuilding as well as new workplace procedures with an increased emphasis on hygiene and safe practices for patients and providers. Several respondents (15%) shared distress about their inability to provide comfort at the end of life and the pain, fear, and isolation their patients experienced due to the pandemic. One participant responded by sharing a personal experience “I will always remember the experience of not being able to get close to a bereaved mum and felt like she didn't receive the service I would have liked to have given in respect of her daughter and her own grief.” Finally, some respondents (15%) reported ongoing fear associated with COVID-19 including anxiety related to the uncertainty of the pandemic and being essential healthcare workers who dread contracting the virus or spreading it to family and community members

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly impacted healthcare systems around the world with noted financial impact on PPC clinicians globally. To limit virus spread, PPC clinicians have relied on physical distancing, PPE, and novel communication technologies such as telehealth.27 , 28 These clinical practice modifications have altered the landscape of PPC care provision for children with life-limiting illness and their families. The findings from this global survey of PPC clinicians have provided unique insights into the experiences of clinicians worldwide during COVID-19.

We report diverse perspectives of PPC providers from a variety of clinical experiences and backgrounds in multiple regions around the world in the context of the pandemic. Despite respondent heterogeneity, many clinicians experienced similar experiences related to COVID-19. Region and income status did not appear to influence the impact of COVID-19 on clinical practice. Workflow changes have created a feeling of disconnectedness for PPC clinicians, in part due to perceived inadequacies of virtual communication and lack of consistent interaction. However, some clinicians emphasized an increased feeling of closeness to their colleagues despite pandemic challenges, in the context of a shared mission, an increased appreciation of the value of missing team members, and deliberate efforts to remain connected during the pandemic. The data suggest that encouraging shared purpose and promoting thoughtful approaches for collaboration and communication despite physical separation may alleviate some of the emotional strain and feelings of disconnection caused by COVID-19. These findings corroborate recent work reported by non-PPC clinicians caring for patients during the pandemic.29

Globally, the financial impact of the pandemic on PPC clinicians with respect to personal income and employment loss is alarming. Great strides have been made over the past decade to expand the reach of PPC services in LLMICs,20 , 22 , 30 , 31 and efforts must be made to ensure that the PPC workforce withstands the pandemic. PPC should be a clear part of the institutional, national, and international response to the pandemic with attentiveness toward programmatic coverage models which foster sustained services. Concerted efforts to provide access to pain medicine, personal protective equipment, and financial support should be available to ensure that PPC clinicians continue to provide quality care for children and their families at the end-of-life.32

Technology was perceived as both helpful and a hinderance to high quality communication by PPC clinicians. Although some clinicians highlighted the benefits of telehealth with respect to reducing travel for patients and families, the majority of respondents described in-person communication as superior to virtual modalities. In particular, PPC clinicians felt that telehealth limited their ability to assess symptoms, reliably recognize nonverbal cues, and provide an empathic presence. While telehealth and technological communication strategies are helpful and likely to play an important role in the future of medical care, further investigation is needed to determine the risk-benefit ratio for utilization of technologies in provision of patient- and family-centered PPC.33 , 34

PPC clinicians also describe heightened distress during the pandemic, often in the context of being unable to provide what they feel is optimal care for patients and families. Recognizing and naming the sources of moral distress are critical first steps in addressing distress amongst PPC clinicians worldwide.35 Strategies exist to promote connection and resilience, which should serve as guideposts for those practicing global PPC during the pandemic, including: 1) promoting a shared team mission, 2) focusing on those things we can control, and 3) continuing to build therapeutic alliance with patients and families.18 , 36 PPC clinicians further described personal health concerns and struggles related to COVID-19, including the impact of infection on loved ones and colleagues. PPC clinicians must have access to self-care and resilience-building resources and services to continue to provide compassionate care for patients and their families.36 , 37

Strengths of this study include international and interdisciplinary collaboration in study design and survey development and wide distribution to global PPC clinicians. Several limitations in this study also warrant consideration. First, we used convenience sampling which is a limitation, and it was not possible to determine the total number of people who received the survey due to overlapping global listserv memberships; without an accurate denominator, we are unable to know the extent of participant response. Second, the survey was distributed in English; although many PPC clinicians internationally are familiar with English, language barriers may have limited participants or introduced selection bias. Third, survey fatigue resulting in variable denominators per item may have introduced response bias. Fourth, the survey was distributed relatively early in the pandemic as a single time-point for data collection, and the cross-sectional study design cannot capture evolution in response patterns across time. The survey represents a global snapshot of life early in the pandemic, recognizing a vision of shared experience.

In summary, this survey provides insights into the experiences of PPC clinicians during the COVID-19 pandemic from a wide range of resources, clinical settings, and experience, and how these experiences were both similar and unique. Identifying ways of maintaining a common mission and purpose, appropriate use of technological communication strategies, and access to self-care and resilience building resources are critical for PPC clinicians to navigate the ongoing pandemic. The financial effects of the pandemic on PPC clinicians are concerning and concerted efforts to ameliorate these economic challenges is important going forward both during the pandemic and even beyond. As PPC clinicians across the world face shared challenges, opportunities exist to apply these important experiences and lessons learned to together improve care for future patients, families, and PPC teams.

Disclosures

This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health. This work was also supported in part by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

Role of Funder/Sponsor

ALSAC had no role in the design and conduct of the study. This work was supported [in part] by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health. The senior author contributed to this paper in a private capacity. No official support or endorsement by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs is intended, nor should be inferred.

Contributors’ Statement

Drs. McNeil, Kaye, and Weaver conceptualized and designed the study, performed the qualitative content analysis and drafted the initial manuscript, reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Drs. Rosenberg and Wiener designed the survey and reviewed and revised the manuscript

Drs Graetz, Baker, and Downing adapted the survey to a global audience, facilitated distribution of the survey and reviewed and revised the manuscript

Mr. Vedaraju, Mr. Ranadive, and Dr. Devidas performed the statistical analysis and reviewed and revised the manuscript.

All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest for this article to disclose.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health. This work was also supported in part by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC). Additionally, we appreciate the assistance of Drs. Veronica Dussel, Megan Doherty, Ursula Sansom-Daly, Eduardo Velasco Guzman, and Ms Abigail Fry for their assistance in piloting the survey.

References

- 1.Hoang A, Chorath K, Moreira A. COVID-19 in 7780 pediatric patients: a systematic review. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;24 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blumenthal D, Fowler EJ, Abrams M, Collins SR. Covid-19 - Implications for the health care system. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1483–1488. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb2021088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parri N, Lenge M, Buonsenso D. Coronavirus infection in pediatric emergency departments (CONFIDENCE) research group. Children with Covid-19 in pediatric emergency departments in Italy. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:187–190. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2007617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zimmermann P, Curtis N. COVID-19 in children, pregnancy and neonates: a review of epidemiologic and clinical features. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39:469–477. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heald-Sargent T, Muller WJ, Zheng X. Age-related differences in nasopharyngeal severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) levels in patients with mild to moderate coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:902–903. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.3651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leeb RT, Price S, Sliwa S. COVID-19 trends among school-aged children - United States, March 1-september 19, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1410–1415. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6939e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bellino S, Punzo O, Rota MC. COVID-19 WORKING GROUP. COVID-19 disease severity risk factors for pediatric patients in Italy. Pediatrics. 2020;146 doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-009399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kainth MK, Goenka PK, Williamson KA. Northwell health covid-19 research consortium. early experience of covid-19 in a us children's hospital. Pediatrics. 2020;146 doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-003186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberton T, Carter ED, Chou VB. Early estimates of the indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and child mortality in low-income and middle-income countries: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e901–e908. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30229-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fausto J, Hirano L, Lam D. Creating a palliative care inpatient response plan for COVID-19-the UW medicine experience. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60:e21–e26. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Talawadekar P, Khanna S, Dinand V. How the COVID-19 pandemic experience has affected pediatric palliative care in Mumbai. Indian J Palliat Care. 2020;26(Suppl 1):S17–S20. doi: 10.4103/IJPC.IJPC_189_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou X, Cai S, Guo Q. Responses of pediatric palliative care to the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Pediatr Res. 2020;11 doi: 10.1038/s41390-020-01137-3. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Curtis JR, Kross EK, Stapleton RD. The importance of addressing advance care planning and decisions about do-not-resuscitate orders during novel coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA. 2020;323:1771–1772. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Downar J, Seccareccia D. Associated medical services inc. educational fellows in care at the end of life. Palliating a pandemic: "all patients must be cared for". J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39:291–295. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.11.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chua IS, Jackson V, Kamdar M. Webside manner during the COVID-19 pandemic: maintaining human connection during virtual visits. J Palliat Med. 2020;23:1507–1509. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2020.0298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuntz JG, Kavalieratos D, Esper GJ. Feasibility and acceptability of inpatient palliative care e-family meetings during COVID-19 pandemic. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60:e28–e32. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weaver MS Rosenberg AR, Fry A, Shostrom V, Wiener L. The impact of the coronavirus pandemic on pediatric palliative care team structures, services, and care delivery. Currently under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Rosenberg AR, Weaver MS, Fry A, Wiener L. Exploring the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on pediatric palliative care clinician personal and professional well-being: a qualitative analysis of U.S. survey data. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;61:805–811. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knapp C., Woodworth L., Wright M. Paediatric palliative care provision around the world: a systematic review. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;57:361–368. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization . World Health Organization Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 30 IGO; Geneva: 2018. Integrating palliative care and symptom relief into paediatrics: A WHO guide for health-care planners, implementers and managers. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caruso Brown A.E., Howard S.C., Baker J.N., Ribeiro R.C., Lam C.G. Reported availability and gaps of paediatric palliative care in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review of published data. J Pall Med. 2014;17:1–14. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2014.0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Downing J, Powell RA, Marston J. Children's palliative care in low- and middle-income countries. Arch Dis Child. 2016;101:85–90. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2015-308307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friedrichsdorf S.J., Remke S., Hauser J. Development of a pediatric palliative care curriculum and dissemination model: education in palliative and end-of-life care (EPEC) Pediatr J. Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;58:707–720. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clark J. Reframing global palliative care advocacy for the sustainable development goal era: a qualitative study of the views of international palliative care experts. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;56:363–370. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dillman D, Smith J, Christian L. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; Hoboken, NJ: 2009. Internet, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: the tailored design method. [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Bank Open Data. Countries and economics. 2020. https://data.worldbank.org/ Accessed October 12, 2020.

- 28.Etkind SN, Bone AE, Lovell N. The role and response of palliative care and hospice services in epidemics and pandemics: a rapid review to inform practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60:e31–e40. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bettini EA. COVID-19 pandemic restrictions and the use of technology for pediatric palliative care in the acute care setting. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2020;22:432–434. doi: 10.1097/NJH.0000000000000694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaul V, Shah VH, El-Serag H. Leadership during crisis: lessons and applications from the COVID-19 pandemic. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:809–812. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.04.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knaul FM, Farmer PE, Krakauer EL. Lancet commission on palliative care and pain relief study group. Alleviating the access abyss in palliative care and pain relief-an imperative of universal health coverage: the Lancet Commission report. Lancet. 2018;391:1391–1454. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32513-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.WHA67.19. S-sWHA . World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland; 2014. Strengthening of palliative care as a component of comprehensive care throughout the life course. [Google Scholar]

- 32.The lancet. palliative care and the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395:1168. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30822-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.André N. Covid-19: breaking bad news with social distancing in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67:e28524. doi: 10.1002/pbc.28524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hart JL, Turnbull AE, Oppenheim IM, Courtright KR. Family-centered care during the COVID-19 era. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60:e93–e97. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Evans AM, Jonas M, Lantos J. Pediatric palliative care in a pandemic: role obligations, moral distress, and the care you can give. Pediatrics. 2020;146 doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wallace CL, Wladkowski SP, Gibson A, White P. Grief During the COVID-19 pandemic: considerations for palliative care providers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60:e70–e76. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosenberg AR. Cultivating deliberate resilience during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:817–818. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]