SIMPLISTIC POLICY; SPARSE EVIDENCE

The UK Secretary of State for Health and Social Care’s announcement that all consultations should henceforth be remote by default1 recurred like a discordant leitmotif in the recent Royal College of General Practitioners’ virtual conference, A Fresh Approach to General Practice.2 Speakers and audience members alike acknowledged that remote consulting has some real strengths, but recoiled from the idea of remote as the norm from which the traditional face-to-face consultation would deviate.

Most published research on remote consultations is either marginal to general practice (for example, trials of video appointments for hospital outpatients with chronic stable conditions)3 or lacking in granularity (for example, predominantly quantitative studies of telephone-first ‘demand management’).4 One detailed study of remote general practice consultations concluded that ‘efficiency’ gains, such as shorter consultations, may occur at the expense of other aspects of consultation quality, including information richness, shared decision making, and safety netting,5 though another interpretation of this non-randomised study is that more patients with complex problems book face-to-face. A randomised trial of telephone triage in general practice found an overall reduction in efficiency because of double-handling of problems.6 Studies of e-consultations7 and workload modelling8 came to similar conclusions.

A MORE COMPLEX REALITY

Clinicians have raised concerns that a remote-by-default service brings numerous risks, including to relationship-based care, continuity of care, physical examination and therapeutic touch, health equity (for example, the long consultation to address complex needs), digital inclusion, ‘doorknob disclosures’, advance care planning, effective safety netting, early detection of cancer through clinical intuition and timely investigation, clinician stress and wellbeing, and professional training and development.9–12 A recent qualitative study of the patient and carer experience of check-up calls for dementia during the pandemic suggested a somewhat transactional character and poor match to needs.13 On the other hand, remote consulting has obvious benefits in rural and remote settings, and for clinicians who are shielding, in quarantine, or have caring responsibilities. And they are popular with some — though not all — patient groups.

The clinical consultation is not a mere transaction. It is a social — indeed, psychodynamic — interaction involving a series of micro-level judgements oriented around the question: ‘What is the best course of action for this patient, at this time, given all the issues at play?’14 The choice between face-to-face, telephone, video, and e-consultation is thus an ethical one that takes account of how multiple factors — clinical, sociocultural, technical, organisational, and so on — play out for a particular patient at a particular moment of need. Clinicians’ resistance to technological innovation is explained in terms of nuanced and deeply held professional standards of excellence, not by stubbornness or fear of technology.15

A RICHER MODEL OF REMOTE CONSULTING …

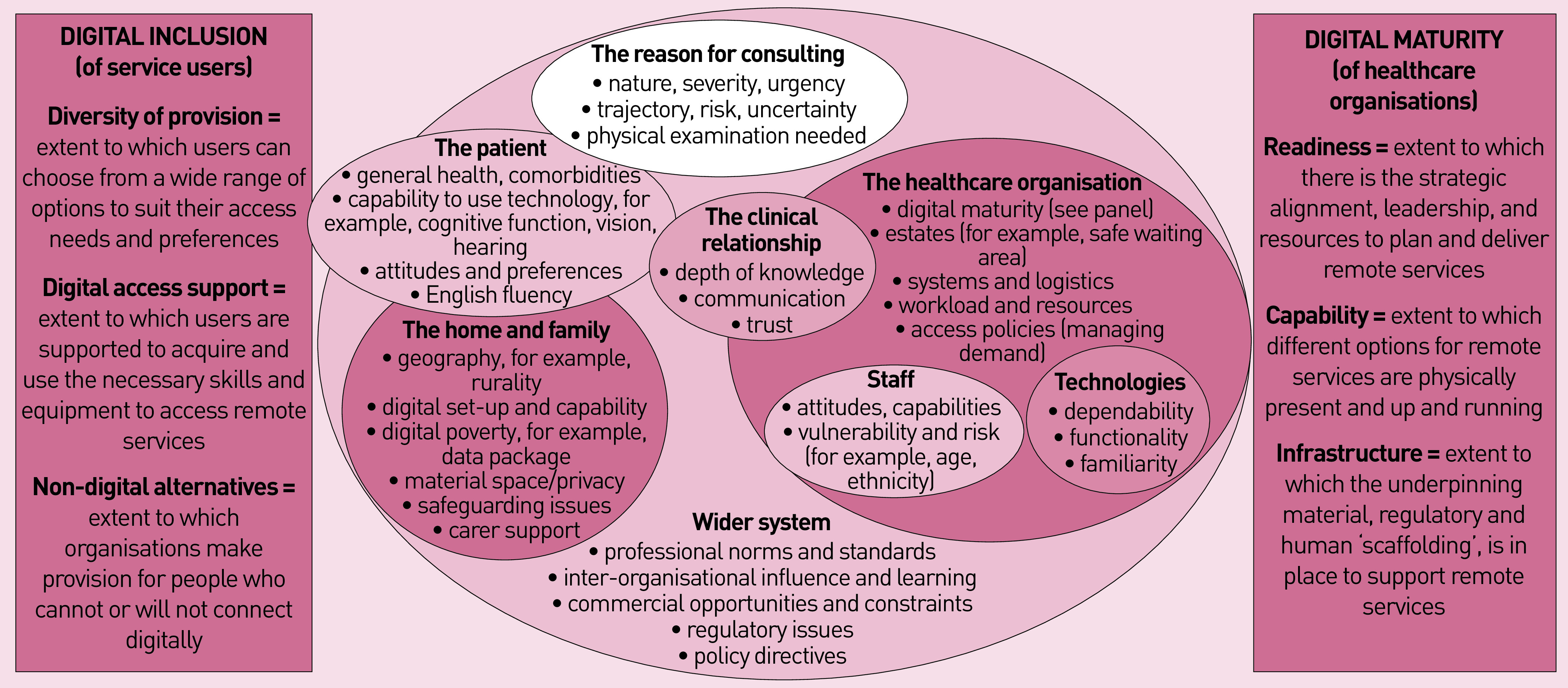

The Remote by Default research study, a collaboration between the Universities of Oxford and Plymouth and the Nuffield Trust (https://www.phc.ox.ac.uk/research/interdisciplinary-research-in-health-sciences/research-studies/remote-by-default-care), has been exploring how technology can be harnessed to support excellent primary care. Using workshops, interviews, and focus groups of clinicians, service users, and other stakeholders, we have begun to map the multiple interacting influences on the choice of consultation modality (Figure 1). This choice is governed not by hard and fast rules but by maxims (rules of thumb), which hold some but not all of the time and which may conflict with other maxims.

Figure 1.

The multiple interacting influences on the choice of consultation modality.

For example, telephone or video-consultations are often but not always appropriate for stable, predictable long-term conditions where physical examination is not needed. Pandemic measures led many patients with unstable and unpredictable acute illness to be channelled to less-than-ideal remote assessments.

A remote consultation may be less appropriate if there are relevant issues in the patient’s general health, such as comorbidities or visual impairment, technical capabilities, English fluency, or personal preferences. In general, though not invariably, remote consultations are easier and less risky if there is a pre-existing clinical relationship and the patient is known to the practice.

Patients’ home and family circumstances vary hugely; successful consulting from home depends on access to private space, digital setup, carer support, and safeguarding. Digital inclusion requires practices to offer choice of modality, support the less digitally skilled as needed, and ensure sufficient face-to-face slots to accommodate the digitally hesitant.16,17 However, when physical distancing restrictions apply, availability of face-to-face consultations may be constrained by estates (for example, safe waiting areas) and availability of practice staff. Staff who are shielding or quarantining may welcome remote consulting, but will need extension of the practice’s digital infrastructure to their homes.

Although the telephone is a familiar and dependable technology, albeit lacking advanced functionality, video and e-consultations may require both clinician and patient to acquire new technology and develop the skills to use it. Remote consultations, even by phone, can be logistically complex and require extensive adaptation of organisational tasks and processes.18

The organisation’s digital maturity not only includes elements of digital infrastructure, such as broadband access, hardware, software, and IT support staff, but also non-technological elements of readiness, such as leadership, strategic sign-off and budget line, and capability, such as software installed, staff trained and confident to use it, and work processes that have been mapped and redesigned.

Factors external to the practice, such as professional norms and standards including advice from royal colleges,19 professional indemnity organisations, the General Medical Council, learning and support from other similar organisations (for example, in improvement collaboratives), regulatory restrictions, policy directives, and advocacy from patient organisations to avoid age, sex, disease, or ethnic stereotyping may also influence — though not fully determine — the choice of consultation modality(ies) to offer a particular patient.

General practice is messy, complex, and characterised by anomalies and exceptions. Even when remote consultations are the policy default, the decision as to whether a remote consultation is best for the patient, the practice staff, and the wider community is an ethical, case-based judgement that cannot be over-protocolised. Research to establish maxims that will facilitate rather than frustrate such judgements is ongoing.

Funding

This work was funded by UKRI COVID-19 Emergency Fund (grant reference: ES/V010069/1)..

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hancock M. The future of healthcare (speech, 30 July) London: UK Government; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Royal College of General Practitioners . A fresh approach to general practice (conference archive) London: RCGP; 2021. https://www.rcgp.org.uk/learning/rcgp-annual-conference.aspx (accessed 23 Feb 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 3.McFarland S, Coufopolous A, Lycett D. The effect of telehealth versus usual care for home-care patients with long-term conditions: a systematic review, meta-analysis and qualitative synthesis. J Telemed Telecare. 2019 doi: 10.1177/1357633X19862956.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newbould J, Ball S, Abel G, et al. A ‘telephone first’ approach to demand management in English general practice: a multimethod evaluation. Health Services Delivery Res. 2019 doi: 10.3310/hsdr07170.. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hammersley V, Donaghy E, Parker R, et al. Comparing the content and quality of video, telephone, and face-to-face consultations: a non-randomised, quasi-experimental, exploratory study in UK primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2019 doi: 10.3399/bjgp19X704573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Campbell JL, Fletcher E, Britten N, et al. Telephone triage for management of same-day consultation requests in general practice (the ESTEEM trial): a cluster-randomised controlled trial and cost-consequence analysis. Lancet. 2014;384(9957):1859–1868. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Banks J, Farr M, Salisbury C, et al. Use of an electronic consultation system in primary care: a qualitative interview study. Br J Gen Pract. 2018 doi: 10.3399/bjgp17X693509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Salisbury C, Murphy M, Duncan P. The impact of digital-first consultations on workload in general practice: modeling study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(6):e18203. doi: 10.2196/18203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murphy M, Salisbury C. Relational continuity and patients’ perception of GP trust and respect: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2020 doi: 10.3399/bjgp20X712349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.de Zulueta P. Touch matters: COVID-19, physical examination and 21st century general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2020 doi: 10.3399/bjgp20X713705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Khan N, Jones D, Grice A, et al. A brave new world: the new normal for general practice after the COVID-19 pandemic. BJGP Open. 2020 doi: 10.3399/bjgpopen20X101103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Jones D, Neal RD, Duffy SR, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the symptomatic diagnosis of cancer: the view from primary care. Lancet Oncology. 2020;21(6):748–750. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30242-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tuijt R, Rait G, Frost R, et al. Remote primary care consultations for people living with dementia during the COVID-19 pandemic: experiences of people living with dementia and their carers. Br J Gen Pract. 2021 doi: 10.3399/BJGP.2020.1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Montgomery K. How doctors think: clinical judgement and the practice of medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenhalgh T, Swinglehurst D, Stones R. Rethinking resistance to ‘big IT’: a sociological study of why and when healthcare staff do not use nationally mandated information and communication technologies. Health Services Delivery Res. 2014 doi: 10.3310/hsdr02390.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stone E, Nuckley P, Shapiro R. Digital inclusion in health and care: lessons learned from the NHS Widening Digital Participation Programme 2017–2020. Leeds: Good Things Foundation; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 17.NHS England . Implementing phase 3 of the NHS response to the COVID-19 pandemic. London: NHS England; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wherton J, Shaw S, Papoutsi C, et al. Guidance on the introduction and use of video consultations during COVID-19: important lessons from qualitative research. BMJ Leader. 2020;4:120–123. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Royal College of General Practitioners, NHS England . Principles for supporting high quality consultations by video in general practice during COVID-19. London: NHS England; [Google Scholar]