Abstract

Although essential for control strategies, knowledge about transmission cycles is limited for Venezuelan equine encephalitis complex alphaviruses (VEEVs). After testing 1,398 bats from French Guiana for alphaviruses, we identified and isolated a new strain of the encephalitogenic VEEV species Tonate virus (TONV). Bats may contribute to TONV spread in Latin America.

Keywords: Venezuelan equine encephalitis complex alphavirus, Tonate virus, bats, viruses, French Guiana, meningitis/encephalitis

Venezuelan equine encephalitis complex alphaviruses (VEEVs) are arthropod-borne viruses (arboviruses) (1,2). Most VEE complex viruses can infect livestock and humans, causing predominantly acute febrile illness; some VEE complex viruses, including Tonate virus (TONV), which is the predominant VEE complex virus in French Guiana, also cause lethal encephalitis in humans (3). Clarifying the enzootic transmission cycles of VEEVs is essential for developing control strategies. Some VEEVs infect a broad range of invertebrate and vertebrate hosts, including horses, birds, rodents, and bats (4). Beyond humans, only birds have been identified as vertebrate hosts for TONV by direct virus detection and characterization (5,6). Bats are particularly relevant hosts of zoonotic viruses (7) and are potential hosts of selected VEEV subtypes in Mexico and Trinidad (4,8). To gain more insights into the ecology of VEEVs in French Guiana, we sampled bats and tested them for alphavirus infections using molecular, serologic, and cell-culture–based tools.

The Study

We screened serum samples from 1,398 individual animals representing 25 different bat species collected during 2010–2018 in French Guiana using a broadly reactive alphavirus-specific reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) for viral RNA (Table 1) (9). All animals were released unharmed after sampling.

Table 1. Bats tested for Tonate virus infection by PCR and PRNT, French Guiana*.

| Species | Animals screened by RT-PCR |

PRNT screening, positive/tested | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | Total | ||

|

Anoura geoffroyi

|

48 |

29 |

74 |

40 |

50 |

13 |

254 |

1/13 |

| Artibeus lituratus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 0 |

| A. obscurus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 10 | 0/10 |

|

A. planirostris

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

21 |

35 |

56 |

1/10 |

| Carollia perspicillata | 3 | 6 | 14 | 6 | 97 | 119 | 245 | 1/17 |

| Cynomops planirostris | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| Dermanura cinerea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 16 | 25 | 0 |

| Desmodus rotundus | 1 | 1 | 5 | 13 | 0 | 2 | 22 | 1/13 |

|

Lonchorhina inusitata

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

3 |

6 |

0 |

| Molossus molossus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 56 | 35 | 91 | 0/20 |

|

M. rufus

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

9 |

1 |

10 |

0 |

| Noctilio albiventris | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 0 |

|

N. leporinus

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

25 |

26 |

0/20 |

| Phyllostomus latifolius | 5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 |

|

P. hastatus

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

20 |

16 |

30 |

66 |

0 |

| Platyrrhinus brachycephalus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 8 | 11 | 0 |

| P. fusciventris | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 9 | 0 |

|

P. incarum

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

1 |

4 |

0 |

| Pteronotus gymnonotus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 11 | 0 |

|

Pteronotus sp. |

61 |

79 |

33 |

119 |

85 |

81 |

458 |

0/45 |

| Sturnira lilium | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 20 | 26 | 0/8 |

|

S. tildae

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

17 |

8 |

25 |

0 |

| Tonatia saurophila | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 0 |

| Trachops cirrhosus | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 11 | 0/11 |

|

Uroderma bilobatum

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

4 |

6 |

0 |

| Total | 121 | 117 | 128 | 199 | 391 | 442 | 1398 | 4/167 |

*PCR-positive bat species and sample are highlighted in bold. was conducted using a screening dilution of 1:50 only because sample volumes were limited. PRNT, plaque reduction neutralization test; RT-PCR, reverse transcription PCR.

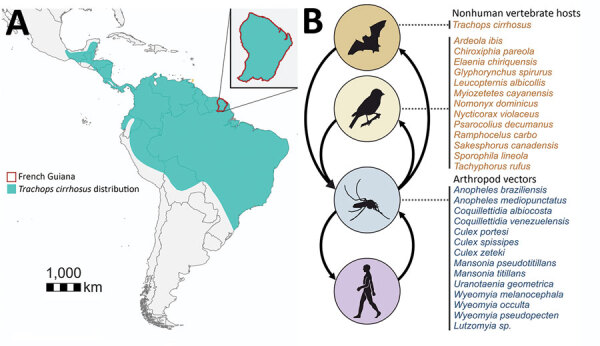

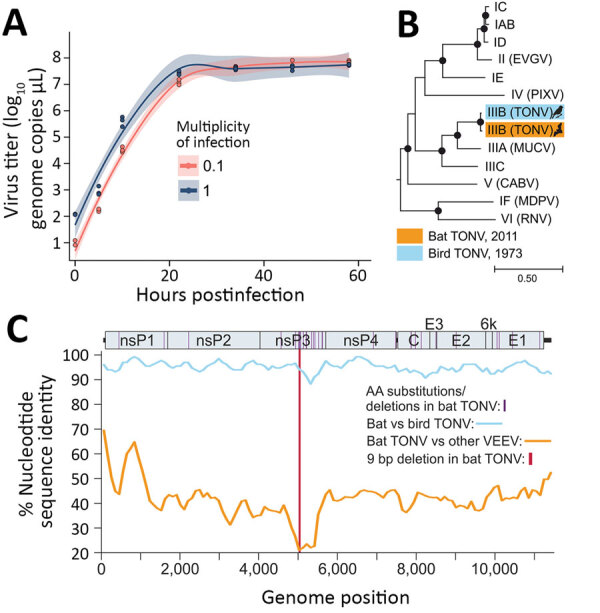

The overall TONV detection rate among all tested animals was 0.07% (95% CI −0.07% to 0.21%). Only 1 apparently healthy fringe-lipped bat (Trachops cirrhosus) sampled in 2011 was PCR-positive; we classified the virus as TONV (also known as VEEV subtype IIIB) upon amplicon sequencing (6). Among 11 individual fringe-lipped bats, the detection rate was 9.1% (95% CI −11.2% to 29.3%) (Figure 1, panel A). The TONV-positive sample was quantified by real-time RT-PCR using strain-specific oligonucleotides and an in vitro transcribed RNA standard (Table 2). Although the concentration of viral RNA in this sample was low, 78.5 genome copies/μL of blood, the virus was isolated on Vero E6 cells, suggesting potential to infect cells of primate origin. Successful isolation was consistent with highly efficient replication in cell culture, reaching 107 copies/µL of supernatant within 24 hours at different multiplicities of infection (Figure 2, panel A).

Figure 1.

Tonate virus hosts and cycles for study of Venezuelan equine encephalitis complex alphavirus in bats, French Guiana. A) Geographic location of French Guiana in South America and distribution of fringe-lipped bats according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List (https://www.iucnredlist.org/). B) Schematic transmission cycles of TONV according to data from this study and preliminary studies (5,6).

Table 2. Oligonucleotides for quantification of TONV, French Guiana*.

| Name | Sequence, 5′ → 3′ | Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| Forward primer | CATTGTCATAGCCAGCAGAGTTCT | 400 nM |

| Reverse primer | GACTTGATACCTTTGACGATGTTGTC | 400 nM |

| Probe (FAM-labeled) | CGCGAACGTCTGACCAACTCACCCT | 200 nM |

*We carried out 25 μL real-time RT-PCR reactions using the Superscript III one-step RT-PCR system with Platinum Taq polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, https://www.thermofisher.com). Reactions were set up with 5 μL extracted RNA; 12.5 μL of 2× reaction buffer; 0.4 μL of a 50 mM magnesium sulfate solution; 1 μg of nonacetylated bovine serum albumin; and 1 μL enzyme. Amplification was conducted at 50°C for 15 min, followed by 95°C for 3 min and 45 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 58°C for 30 s with fluorescence, read at the 58° annealing/extension step on a LightCycler 480 thermocycler (Roche, https://www.roche.com). FAM, fluorescein amidite; RT-PCR, reverse transcription PCR.

Figure 2.

Characterization of bat TONV in study of VEE complex alphavirus in bats, French Guiana. (For additional discussion of methods, see Appendix.) A) Growth kinetics of the new bat TONV on Vero E6 cells in 24-well plates. (B) Maximum-likelihood phylogeny of TONV and members of the VEEV antigenic complex based on full genome nucleotide sequences. Eastern equine encephalitis virus (NC_003899) was included as an outgroup. Viruses are named according to the VEEV subtype classification: IAB/IC/ID/IE/IIIC, Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus; IF, Mosso das Pedras virus; II, Everglades virus; IIIA, Mucambo virus; IIIB, Tonate virus; IV, Pixuna virus; V, Cabassou virus; VI, Rio Negro virus. Bootstrap support above 90% is highlighted by filled circles. C) Percentage nucleotide sequence identity between TONV isolates and other viruses of the VEE antigenic complex. Consensus preparation was done using Geneious 9.1.8 (https://www.geneious.com) by mapping to the TONV CaAn 410d complete genome (GenBank accession no. NC 038675.1) as reference. The median coverage for consensus preparation was 5,504 (range 5–11,605). TONV, Tonate virus; VEE, Venezuelan equine encephalitis.

The complete viral genome was generated from the original isolate by high-throughput sequencing (MiSeq V3 chemistry; Illumina, https://www.illumina.com). In a complete genome-based maximum likelihood phylogeny, the bat-associated TONV (GenBank accession no. MW809725) clustered with the only available TONV strain, which was isolated in 1973 from a bird (Figure 2, panel B). Despite ≈40 years between the 2 TONV isolations and despite the divergent vertebrate hosts, the nucleotide identity between the bat-associated and the bird-associated TONVs was 98.1%, averaged over the whole genome. The high rate of genomic conservation is probably a consequence of purifying selection that is a predominant evolutionary force acting on arboviruses because of their need to infect both vertebrate and arthropod cells (10). Nucleotide identity was <90% only within the hypervariable region (HVR) located in the alphaviral genomic region encoding the nonstructural protein 3 (nsP3) (Figure 2, panel C). In total, 31 aa substitutions or deletions were present in the bat-associated TONV compared with the bird-associated TONV, of which 14 were located within the nsP3 HVR (p<0.0001 by χ2 test comparing the HVR to other genomic regions) (Figure 2, panel C). At the 5′ end of the HVR, the bat-associated TONV showed a larger in-frame deletion of 9 nt compared with the bird-associated TONV. This genomic region was covered by roughly 8,000 reads, supporting the deletion not being caused by technical mistakes during sequencing (Appendix Figure). The nsP3 HVR is assumed to play a crucial role for vector adaptation of VEEVs (11), supported by experimental evidence showing that exchanging the nsP3 of the alphaviruses chikungunya virus and o’nyong nyong virus dramatically affects the ability of chimeras to infect Anopheles and Aedes mosquito cells (12). The nsP3 deletion may therefore hypothetically reflect viral adaptation to different invertebrate, and potentially also vertebrate, hosts. Cell culture–based experiments including mosquito, bat, and bird cell lines, as well as in vivo infections, comparing the growth of both TONV isolates and chimeric viruses will be needed to yield definite assessments on the potential effect of the observed HVR deletion on the viral phenotype.

Detection of acute TONV infection in only 1 fringe-lipped bat was not surprising because alphaviral viremia is typically short-lived (13). To examine the frequency of past TONV infections in bats, we tested 167 bat serum samples for TONV-specific neutralizing antibodies by 50% plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT50). We selected the sample set on the basis of availability of sufficient sample volumes; a preference for fringe-lipped bats, the attempt to represent the most abundant bat species investigated in this study; and a focus on bat genera in which VEEV-specific neutralizing antibodies had been detected previously in other countries (4,8). Four bats were seropositive, resulting in an overall TONV seroprevalence of 2.4% (95% CI 0.1%–4.7%) among tested samples. Limited reduction of PFUs at a serum dilution of 1:50 spoke against high antibody titers in those 4 animals and, indeed, no neutralization was observed when those 4 serum samples were tested at a dilution of 1:500. The 4 seropositive bats belonged to the species Anoura geoffroyi (1/13 animals, 7.7%; 95% CI −9.1% to 24.5%), Artibeus planirostris (1/10 animals, 10%; 95% CI −12.6% to 32.6%), Carollia perspicillata (1/17 animals, 5.9%; 95% CI −6.6% to 18.4%), and Desmodus rotundus (1/13 animals, 7.7%; 95% CI −9.1% to 24.5%). All 11 fringe-lipped bats, including the acutely infected PCR-positive animal, showed no detectable neutralization of TONV.

Our serologic data are limited by testing only 1 relatively high serum dilution, and by the inability to differentiate between the neutralization of TONV and of other VEEVs such as Cabassou or Mucambo virus, which occur in geographic proximity to TONV (14). The serologic data therefore support low-level circulation of TONV or of antigenically related VEEVs in different bat species. Low prevalence of antibodies neutralizing TONV is consistent with the detection of VEEV antibodies in Desmodus rotundus (4.9%), Carollia perspicillata (6.9%), Artibeus spp. (4.4%), and Noctilio leporinus (7.1%) bats in Trinidad by epitope‐blocking ELISA and hemagglutination inhibition tests (8).

Conclusion

The breadth of the VEEV host range remains unknown for most VEEV species or subtypes (1). This lack of information is particularly true for TONV, which has been found only in birds and humans so far. Identifying bats as naturally infected TONV hosts is thus a key finding, indicating a broad vertebrate host range for TONV. The TONV host range may hypothetically include other vertebrates, such as rodents, based on natural infections by other VEEVs closely related to TONV (4) and by preliminary data on TONV infections in sentinel mice in the 1970s (5) (Figure 1, panel B). In French Guiana, 12% of the overall human population shows serologic evidence for prior TONV infection, but the regions of highest risk for TONV infection remained unclear. One serosurvey reported highest seroprevalence in the coastal regions (35%) (5), whereas another serosurvey reported highest seroprevalence in inland savannah areas (53%) (15). The broad distribution of TONV might be explained by a broad vertebrate host range adding to the previously known broad invertebrate host range (2,5). Bats are extraordinary species and hosts for many zoonotic viruses and may thus also play a major role in TONV maintenance (7). Future research addressing TONV transmission cycles should include sampling of a broad range of vertebrate animals in ecologically different habitats, ideally including bats and analyses of TONV-competent mosquito bloodmeals.

Appendix. Additional information on Venezuelan equine encephalitis complex alphavirus in bats, French Guiana.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all volunteers and field workers who have helped us during the field sessions.

Authorization for bat capture in French Guiana was provided by the Ministry of Ecology, Environment, and Sustainable Development during 2015–2020 (approval no. C692660703 from the Departmental Direction of Population Protection (DDPP, Rhône, France). All methods (capture and animal handling) were approved by the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Société française pour l’étude et la protection des mammifères, and the Direction de l’environnement, de l’aménagement et du logement (DEAL), Guyane.

This work was supported by European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program through the ZIKAlliance project (grant agreement no. 734548) and Laboratoire d’Excellence Dynamiques éco-évolutives des maladies infectieuses (ANR-11-LABX-0048) of Université de Lyon, within the program Investissements d’Avenir (ANR-11-IDEX-0007).

Biography

Mr. Fischer is a PhD student at the Institute of Virology at Charité-Universitätsmedizin, Berlin, Germany. His primary research interests are diagnostics and epidemiology of emerging viruses.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Fischer C, Pontier D, Filippi-Codaccioni O, Pons J-B, Postigo-Hidalgo I, Duhayer J, et al. Venezuelan equine encephalitis complex alphavirus in bats, French Guiana. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021 Apr [date cited]. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2704.202676

These authors contributed equally to this article.

References

- 1.Forrester NL, Wertheim JO, Dugan VG, Auguste AJ, Lin D, Adams AP, et al. Evolution and spread of Venezuelan equine encephalitis complex alphavirus in the Americas. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005693. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Degallier N, Digoutte J, Pajot F. Épidémiologie de deux arbovirus du complexe VEE en Guyane Francaise: données préliminaires sur les relations virus-vecteurs. Cahiers ORSTOM Série Entomologie Médicale et Parasitologie. 1978;16:209–21. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hommel D, Heraud JM, Hulin A, Talarmin A. Association of Tonate virus (subtype IIIB of the Venezuelan equine encephalitis complex) with encephalitis in a human. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:188–90. 10.1086/313611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sotomayor-Bonilla J, Abella-Medrano CA, Chaves A, Álvarez-Mendizábal P, Rico-Chávez Ó, Ibáñez-Bernal S, et al. Potential sympatric vectors and mammalian hosts of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus in southern Mexico. J Wildl Dis. 2017;53:657–61. 10.7589/2016-11-249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Digoutte J. Ecologie des Arbovirus et Leur Rôle Pathogène chez L’Homme en Guyane Française. Cayenne, French Guiana: Institut Pasteur de la Guyane Française—Groupe I.N.S.E.R.M. U79; 1975.

- 6.Mutricy R, Djossou F, Matheus S, Lorenzi-Martinez E, De Laval F, Demar M, et al. Discriminating tonate virus from dengue virus infection: a matched case-control study in French Guiana, 2003-2016. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;102:195–201. 10.4269/ajtmh.19-0156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olival KJ, Hosseini PR, Zambrana-Torrelio C, Ross N, Bogich TL, Daszak P. Host and viral traits predict zoonotic spillover from mammals. Nature. 2017;546:646–50. 10.1038/nature22975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thompson NN, Auguste AJ, Travassos da Rosa AP, Carrington CV, Blitvich BJ, Chadee DD, et al. Seroepidemiology of selected alphaviruses and flaviviruses in bats in Trinidad. Zoonoses Public Health. 2015;62:53–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grywna K, Kupfer B, Panning M, Drexler JF, Emmerich P, Drosten C, et al. Detection of all species of the genus Alphavirus by reverse transcription-PCR with diagnostic sensitivity. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:3386–7. 10.1128/JCM.00317-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woelk CH, Holmes EC. Reduced positive selection in vector-borne RNA viruses. Mol Biol Evol. 2002;19:2333–6. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Götte B, Liu L, McInerney GM. The enigmatic alphavirus non-structural protein 3 (nsP3) revealing its secrets at last. Viruses. 2018;10:105. 10.3390/v10030105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saxton-Shaw KD, Ledermann JP, Borland EM, Stovall JL, Mossel EC, Singh AJ, et al. O’nyong nyong virus molecular determinants of unique vector specificity reside in non-structural protein 3. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e1931. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bozza FA, Moreira-Soto A, Rockstroh A, Fischer C, Nascimento AD, Calheiros AS, et al. Differential shedding and antibody kinetics of Zika and chikungunya viruses, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019;25:311–5. 10.3201/eid2502.180166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aguilar PV, Estrada-Franco JG, Navarro-Lopez R, Ferro C, Haddow AD, Weaver SC. Endemic Venezuelan equine encephalitis in the Americas: hidden under the dengue umbrella. Future Virol. 2011;6:721–40. 10.2217/fvl.11.50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Talarmin A, Trochu J, Gardon J, Laventure S, Hommel D, Lelarge J, et al. Tonate virus infection in French Guiana: clinical aspects and seroepidemiologic study. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;64:274–9. 10.4269/ajtmh.2001.64.274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix. Additional information on Venezuelan equine encephalitis complex alphavirus in bats, French Guiana.