Abstract

Since 2016, OXA-244–producing Escherichia coli has been increasingly isolated in France. We sequenced 97 OXA-244–producing E. coli isolates and found a wide diversity of sequence types and a high prevalence of sequence type 38. Long-read sequencing demonstrated the chromosomal location of blaOXA-244 inside the entire or truncated Tn51098.

Keywords: carbapenemase, OXA-48–like, Enterobacteriaceae, clones, whole-genome sequencing, next-generation sequencing, MLST, antimicrobial resistance, Escherichia coli, AMR, bacteria, France, carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales

Carbapenems are the last line antimicrobial drugs for treating infections caused by multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales. The global dissemination of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales (CPE; formerly known as carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae) pose a serious threat to public health (1). Oxacillin (OXA) 244, a single amino-acid variant of OXA-48 (Arg-222-Gly) (2), is an emerging carbapenemase variant in several countries in Europe (3–7). During 2013–2019, the French National Reference Center received a continuously increasing number of OXA-244–producing isolates for antimicrobial resistance (AMR) testing. OXA-244–producing isolates increased from 0 in 2012 to 72 in 2019. In France, OXA-244–producing Enterobacteriaceae represent 2.4% of all CPE and represented 3.4% of OXA-48–like producing CPE in 2019 (8). In addition, this tendency might represent only a fraction of OXA-244–producing Enterobacteriaceae because this variant is difficult to detect on CPE screening media due to the low hydrolytic activity of this carbapenemase (8). OXA-244 is found mainly in Escherichia coli isolates (6). The blaOXA-244 gene is described in only 1 type of transposon, Tn51098, a 21.9-kb IS1R-based composite transposon that includes a truncated Tn1999.2 (ΔTn1999.2) and a fragment of the archetypal IncL blaOXA-48–carrying plasmid, pOXA-48 (2).

Previous studies analyzed only a limited number of OXA-244–producing E. coli of an epidemic clone belonging to sequence type (ST) 38 that spread in countries in Europe (3,5,7,9). More data on the epidemiology and genetics of OXA-244 are required to understand its spread in Europe. We used whole-genome sequencing (WGS) to characterize the epidemiology of OXA-244–producing E. coli circulating in France during 2016–2019.

The Study

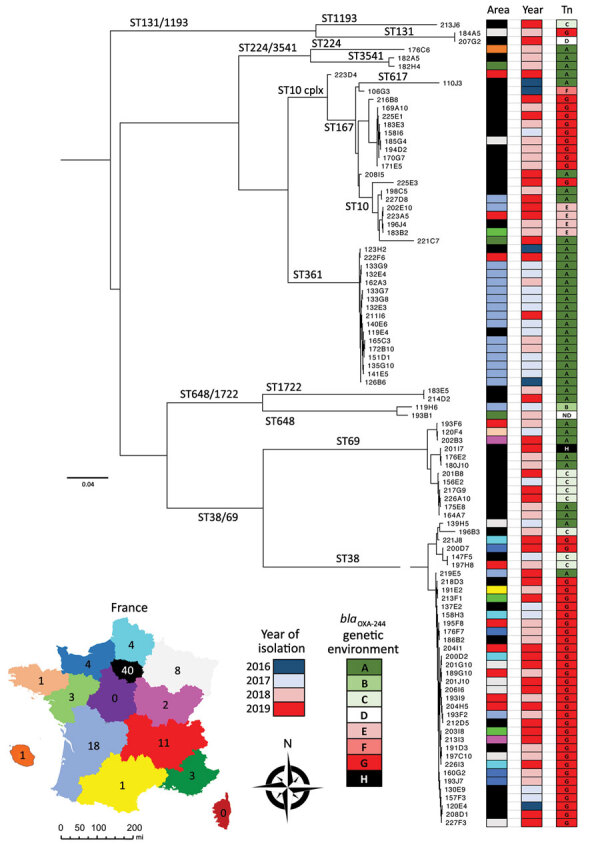

During 2016–2019, the French National Reference Center identified 97 OXA-244–producing E. coli isolates. We performed WGS on all isolates by using the HiSeq (Illumina Inc., https://www.illumina.com) sequencing platform (GenBank accession nos. in Appendix 1 Table). We performed in silico multilocus sequence typing (MLST) by using the MLST 2.0 server (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/MLST). We identified 12 different sequence types (STs); the 5 most prevalent were ST38 (n = 37), ST361 (n = 17), ST69 (n = 12), ST167 (n = 11), and ST10 (n = 8) (Figure 1). Among OXA-244–producing E. coli isolates, the prevalence of ST38 rose from 12% in 2016 and to 47% in 2019.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic relationship and geographic distribution of the 97 OXA-244–producing Escherichia coli isolates recovered in France, 2016–2019. Inset map shows regions of France; colors correspond to areas from which OXA-244–producing E. coli isolates were collected. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using CSIPhylogeny version 1.4 (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/CSIPhylogeny). Scale bar indicates nucleotide substitutions per site. ND, not detected; OXA, oxacillin; ST, sequence type.

On all 97 genomes of OXA-244–producing E. coli, we used a core genome single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)–based approach to create a phylogenetic tree by using CSIPhylogeny (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/CSIPhylogeny). To identify clades within STs, we performed a nested phylogenetic analysis with isolates of each ST to construct a SNP matrix. Isolates within the same clade would be highly suggestive of patient-to-patient cross-transmission of the same strain. We considered 2 strains to be part of the same clade if they were separated by <100 SNPs along their common genome (Appendix 2 Figure). We identified large clades corresponding to clonal dissemination of a single strain in the same area, including 5/12 isolates of ST167 and 15/17 isolates of ST361. We identified <7 different clades of ST38, and most (30/37) isolates belonged to the same clade (Appendix 2 Figure). However, these 30 ST38 isolates were collected in 9 different areas of France and 25 were isolated during 2018–2019 (Figure 1).

Because assembly of regions with repeated sequences was difficult with Illumina WGS data, we sequenced some isolates by using long read nanopore technology by using a MinIon (Oxford Nanopore, https://nanoporetech.com) sequencer (10). We performed WGS on 3 isolates belonging to the most prevalent STs: isolate 119E4 (ST361), isolate 120E4 (ST38), and isolate 156E2 (ST69) (Appendix 1 Table). We found a chromosomal localization of blaOXA-244 gene in the 3 isolates. By combining data obtained by both WGS technologies, we reconstructed the different genetic environments of blaOXA-244 gene and annotated the assembled sequences by using CLC Genomics Workbench version 12.0 software (QIAGEN, https://www.qiagen.com).

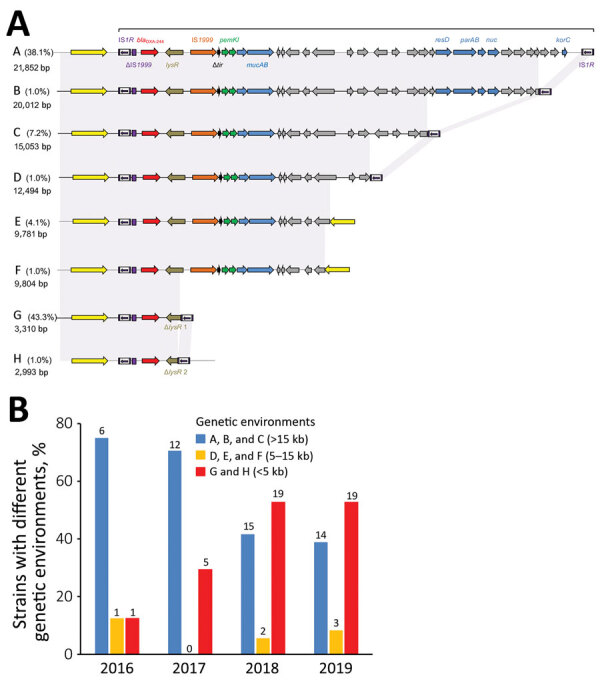

We detected 8 different genetic environments in our collection (Figure 2, panel A). Among the 97 E. coli isolates, 37 (38.1%) possessed the blaOXA-244 gene in Tn51098, a previously described transposon (2,11) (Figure 2, panel A). Among the other 60 (61.9%) isolates, we found blaOXA-244 in the shorter form of Tn51098 (2,933–20,012 bp) (Figure 2, panel A). The blaOXA-244 gene still was systematically included in a truncated Tn1999.2 (ΔTn1999.2), as described in E. coli VAL (2). For 44.3% of isolates, the remnant Tn51098 was reduced in size (42 isolates with genetic environment G and 1 with genetic environment H) (Figure 2, panel A). We noted, the blaOXA-244 gene was included in a ΔTn1999.2 where the lysR gene was truncated by the IS1R element. Of the 42 isolates sharing the genetic environment G, 32 (76.1%) belonged to ST38. By separating the type of genetic environment according to the date of isolation, we noticed that the short forms were isolated during 2018–2019 (38/44 strains, 86%) (Figure 2, panel B).

Figure 2.

Genetic relationship and environment of blaOXA-244 genes identified in Escherichia coli isolates collected during 2016–2019, France. A) Schematic representation of the close genetic context of blaOXA-244 genes (A–H) identified in E. coli. Arrows indicate direction of the genes. Yellow indicates chromosomal genes; purple indicates mobile elements; red indicates β-lactamase genes; green indicates toxin–antitoxin genes; blue indicates genes with known function; and gray indicates hypothetical proteins. B) The relationship between the close genetic environment of blaOXA-244 gene and the year of isolation. OXA, oxacillin.

Discussion

Dissemination of ST38 OXA-244–producing E. coli has been observed in many countries in Europe (3–7) and a few other countries around the world (12,13). However, most of these studies focused on ST38. Our results confirm the phenomenon of OXA-244–producing E. coli isolates in France because 38% of isolates in our study belonged to ST38. In addition, we observed an increased number of ST38 isolates during 2018–2019. Phylogenetic analysis identified a substantial clade inside ST38 (Appendix 2 Figure), but massive dissemination of this clone in France likely does not correspond to cross transmission of a single strain in different areas. The few SNP differences identified among ST38 isolates suggest this clade emerged recently. Accordingly, inside this compact ST38, the <100 SNP cutoff used to discriminate between 2 clades might be lowered because it was recently described for another high-risk clone, Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase–producing K. pneumoniae ST258 (14).

The other common STs noted in our study are ST361, ST167, ST69 and ST10. In Europe, OXA-244–producing E. coli of ST69, ST167, and ST361 have been reported in Denmark (6), and ST69 and ST10 in Switzerland. Unlike what we observed with ST38, clones observed inside ST167 and ST361 mostly correlate with the same geographic area suggesting patient-to-patient cross-transmission.

As previously described for ST38 E. coli VAL (2), we demonstrated the chromosomal location of the blaOXA-244 gene in 3 isolates belonging to the 3 main STs, ST38, ST361, and ST69. The chromosomal localization of blaOXA-244 together with the intrinsic lower hydrolytic activity of OXA-244, compared with OXA-48, contribute to the difficulties in accurately detecting OXA-244–producing E. coli using classical screening media (8,15), suggesting a large underestimation of the real spread of OXA-244 producers.

In 2013, the blaOXA-244 gene initially was reported to be embedded in a 21,852-bp transposon Tn51098, which contains ΔTn1999.2 (2). This structure still is present in 38.1% of OXA-244–producing E. coli. To our knowledge, Tn51098 is the sole genetic structure reported for blaOXA-244. In our collection, blaOXA-244 was embedded in truncated forms of Tn51098 in most isolates. Of note, in most (86.5%) ST38 OXA-244–producing E. coli the close genetic context of the blaOXA-244 gene was reduced to a small 3,310-bp fragment matching Tn51098 and corresponding to a truncated form of the Tn1999.2. In addition, the most recently collected isolates possess short versions of the Tn51098 compared with the isolates collected earlier (Figure 2, panel B). The effect on the clonal dissemination of this genome reduction around blaOXA-244 gene (e.g., better fitness) remains undetermined. Further analysis on the blaOXA-244 close genetic environment could elucidate the effects of this genome reduction.

Global characteristics and NCBI accession numbers of OXA-244–producing Escherichia coli isolates.

Phylogenetic tree of OXA-244–producing Escherichia coli in 5 major sequence types, France.

Biography

Dr. Emeraud is an assistant professor at the INSERM, Le Kremlin-Bicêtre, France. Her main research interests include epidemiology, genetics, and biochemistry of β-lactamases in gram negative bacteria.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Emeraud C, Girlich D, Bonnin RA, Joussett AB, Naas T, Dortet L. Emergence and polyclonal dissemination of OXA-244–producing Escherichia coli, France. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021 Apr [date cited]. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2704.204459

References

- 1.Nordmann P, Dortet L, Poirel L. Carbapenem resistance in Enterobacteriaceae: here is the storm! Trends Mol Med. 2012;18:263–72. 10.1016/j.molmed.2012.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Potron A, Poirel L, Dortet L, Nordmann P. Characterisation of OXA-244, a chromosomally-encoded OXA-48-like β-lactamase from Escherichia coli. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2016;47:102–3. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2015.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Masseron A, Poirel L, Falgenhauer L, Imirzalioglu C, Kessler J, Chakraborty T, et al. Ongoing dissemination of OXA-244 carbapenemase-producing Escherichia coli in Switzerland and their detection. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2020;97:115059. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2020.115059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Increase in OXA-244-producing Escherichia coli in the European Union/European Economic Area and the UK since 2013. Stockholm: the Centre; 2020. [cited 2020 Feb 18]. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/RRA-E-coli-OXA-244-producing-E-coli-EU-EEA-UK-since-2013.pdf.

- 5.Kremer K, Kramer R, Neumann B, Haller S, Pfennigwerth N, Werner G, et al. Rapid spread of OXA-244-producing Escherichia coli ST38 in Germany: insights from an integrated molecular surveillance approach; 2017 to January 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020;25:2000923. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.25.2000923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hammerum AM, Porsbo LJ, Hansen F, Roer L, Kaya H, Henius A, et al. Surveillance of OXA-244-producing Escherichia coli and epidemiologic investigation of cases, Denmark, January 2016 to August 2019. Euro Surveill. 2020;25:25. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.18.1900742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falgenhauer L, Nordmann P, Imirzalioglu C, Yao Y, Falgenhauer J, Hauri AM, et al. Cross-border emergence of clonal lineages of ST38 Escherichia coli producing the OXA-48-like carbapenemase OXA-244 in Germany and Switzerland. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;56:106157. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.106157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Emeraud C, Biez L, Girlich D, Jousset AB, Naas T, Bonnin RA, et al. Screening of OXA-244 producers, a difficult-to-detect and emerging OXA-48 variant? J Antimicrob Chemother. 2020;75:2120–3. 10.1093/jac/dkaa155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oteo J, Hernández JM, Espasa M, Fleites A, Sáez D, Bautista V, et al. Emergence of OXA-48-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and the novel carbapenemases OXA-244 and OXA-245 in Spain. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68:317–21. 10.1093/jac/dks383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonnin RA, Jousset AB, Gauthier L, Emeraud C, Girlich D, Sauvadet A, et al. First occurrence of the OXA-198 carbapenemase in Enterobacterales. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020;64:e01471–19. 10.1128/AAC.01471-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pitout JDD, Peirano G, Kock MM, Strydom K-A, Matsumura Y. The global ascendency of OXA-48-type carbapenemases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2019;33:e00102–19. 10.1128/CMR.00102-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abril D, Bustos Moya IG, Marquez-Ortiz RA, Josa Montero DF, Corredor Rozo ZL, Torres Molina I, et al. First report and comparative genomics analysis of a blaOXA-244-harboring Escherichia coli isolate recovered in the American continent. Antibiotics (Basel). 2019;8:222. 10.3390/antibiotics8040222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soliman AM, Ramadan H, Sadek M, Nariya H, Shimamoto T, Hiott LM, et al. Draft genome sequence of a blaNDM-1- and blaOXA-244-carrying multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli D-ST69 clinical isolate from Egypt. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2020;22:832–4. 10.1016/j.jgar.2020.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.David S, Reuter S, Harris SR, Glasner C, Feltwell T, Argimon S, et al. ; EuSCAPE Working Group; ESGEM Study Group. Epidemic of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in Europe is driven by nosocomial spread. Nat Microbiol. 2019;4:1919–29. 10.1038/s41564-019-0492-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoyos-Mallecot Y, Naas T, Bonnin RA, Patino R, Glaser P, Fortineau N, et al. OXA-244-producing Escherichia coli isolates, a challenge for clinical microbiology laboratories. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61:e00818–17. 10.1128/AAC.00818-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Global characteristics and NCBI accession numbers of OXA-244–producing Escherichia coli isolates.

Phylogenetic tree of OXA-244–producing Escherichia coli in 5 major sequence types, France.