Abstract

There is an unmet medical need for later-line treatment options for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC). Considering that, beyond progression, co-treatment with bevacizumab and cytotoxic chemotherapy showed less toxicity and a significant disease control rate, we aimed to evaluate the efficacy of capecitabine and bevacizumab. This single-center retrospective study included 157 patients between May 2011 and February 2018, who received bevacizumab plus capecitabine as later-line chemotherapy after progressing with irinotecan, oxaliplatin, and fluoropyrimidines. The study treatment consisted of bevacizumab 7.5 mg/kg on day 1 and capecitabine 1,250 mg/m2 orally (PO) twice daily on day 1 to 14, repeated every 3 weeks. The primary endpoint was progression-free survival (PFS). The median PFS was 4.6 months (95% confidence interval [CI] 3.9–5.3). The median overall survival (OS) was 9.7 months (95% CI 8.3–11.1). The overall response rate was 14% (22/157). Patients who had not received prior targeted agents showed better survival outcomes in the multivariable analysis of OS (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.59, 95% CI 0.43–0.82, P = 0.002) and PFS (HR = 0.61, 95% CI 0.43–0.85, P = 0.004). Bevacizumab plus capecitabine could be a considerably efficacious option for patients with mCRC refractory to prior standard treatments.

Subject terms: Gastrointestinal cancer, Cancer therapy

Introduction

Metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) is one of the most common causes of cancer-related death1. In first- or second-line treatment, the addition of targeted drugs consisting of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) agents (bevacizumab, aflibercept, and ramucirumab) and anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) agents (cetuximab and panitumumab) to oxaliplatin or irinotecan doublets improved survival outcomes with median overall survival more than 2 years2–8.

Recent studies on later-line treatments showed promising efficacy among mCRC patients harbouring the following specific genetic alterations: amplified human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)9, neurotrophic receptor tyrosine kinase (NTRK) fusion10, mutated B-Raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase (BRAF)11,12, and mismatch repair deficiency13–15. These newer agents are currently under trial for first-line or second-line rather than later-line treatment administration. However, the incidence of these specific alterations is very low (< 5%) and is not always applicable. Moreover, the different reimbursement policies used for diagnosis and treatment by some countries limit the administration of newer agents to certain patients.

For most patients without these specific target alterations described above, third- or later-line treatment consists of regorafenib or TAS-102—an orally available, small molecular multi-kinase inhibitor and a compound of trifluridine with tipiracil, respectively—which showed survival benefits in a randomised controlled trial16–18. However, the numerical increase in survival duration was < 3 months compared with the placebo. In addition, the aforementioned later-line treatment options only benefit a limited number of patients because of the high cost. Consequently, there is an unmet medical need for easily accessible later-line treatment options with minimal costs.

Capecitabine monotherapy is not recommended for later-line treatment, especially in those who have progressed after treatment with fluoropyridine plus oxaliplatin or irinotecan doublets. However, it has been commonly used in the later-line treatment of patients with refractory mCRC, though the supporting evidence is weak19. Bevacizumab for later-line treatment is not recommended, even for those who were not exposed to first- or second-line treatment20.

Continuation of bevacizumab beyond disease progression with cytotoxic agents and bevacizumab co-therapy showed clinical benefit in patients with mCRC21,22. These studies suggest that bevacizumab therapy after disease progression may have clinical benefit, even in refractory patients treated with bevacizumab. A recent study demonstrated that bevacizumab plus TAS-102 as later-line treatment improved survival rates23. Therefore, we aimed to evaluate the efficacy of the combination of bevacizumab and capecitabine.

Patients and methods

Patients and data collection

We retrospectively accrued 157 mCRC patients who received bevacizumab plus capecitabine as their third- or later-line treatment in Asan Medical Center, Korea, between May 2011 and February 2018. Patients were intolerant or progressed during or within 6 months of the standard irinotecan, oxaliplatin, and fluoropyrimidine therapies. Patients who were previously administered capecitabine were included. The study treatment, which consisted of bevacizumab 7.5 mg/kg on day 1 and capecitabine 1,250 mg/m2 orally (PO) twice daily on day 1 to 14, was repeated every 3 weeks.

Clinical data were obtained from medical records using Asan Biomedical Research Environment (ABLE), an anonymous clinical database system in our institute. The primary endpoint was progression-free survival (PFS) and the secondary endpoints were overall survival (OS), confirmed best overall response, safety outcomes, and a risk factor affecting survival outcomes. For the safety evaluation, we analysed the number and proportion of patients who experienced any events according to the common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE) version 4.03.

To analyse the best overall response, we used the response evaluation criteria in solid tumours (RECIST) version 1.1. We investigate the clinical characteristics of patients who showed an extended lasting response with a combination of bevacizumab and capecitabine. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) of Asan Medical Center, Korea (approval number: 2020–1875). The requirement of obtaining informed consent from patients was waived by the IRBs because of the retrospective nature of this study.

Statistical Analysis

Patients’ demographics, clinicopathological characteristics, and treatment patterns were summarised as numbers (percentages) for categorical variables and means for continuous variables. Survival curves were constructed using paired Kaplan–Meier estimates and analysed using the stratified log-rank test. Univariable and multivariable analysis of PFS and OS were performed using the Cox proportional hazards model. The variables were age, sex, primary site, treatment lines, RAS mutation, previous history of targeted agents, and time from diagnosis of metastatic disease to treatment. In the multivariable analysis, variables with a potential relationship (P < 0.2) in the univariable analyses were included. All reported P-values were two-sided, and a P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient population and treatment summary

The baseline characteristics of the 157 patients are shown in Table 1. The median age was 57 (range, 28–82) years and more than half of the patients had two or more metastatic sites, whereas 33 (21.0%) patients experienced peritoneal seeding. More than half (52.9%) and eight (5.1%) patients had tumours with RAS and BRAF mutations, respectively. Among the patients with RAS and BRAF wild-type, 52 had a history of treatment with targeted agents before capecitabine and bevacizumab, 19 (27.1%) received both bevacizumab and cetuximab, one (1.4%) had bevacizumab without cetuximab, and 32 (45.7%) received only cetuximab treatment.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of all patients (N = 157).

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| < 65 | 116 | 73.9 |

| ≥ 65 | 41 | 26.1 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 85 | 54.1 |

| Female | 72 | 45.9 |

| Primary site | ||

| Right colon | 42 | 26.8 |

| Left colon | 115 | 73.2 |

| Histology | ||

| W/D adenocarcinoma* | 10 | 6.4 |

| M/D adenocarcinoma* | 118 | 75.2 |

| P/D adenocarcinoma* | 29 | 18.5 |

| Site of metastasis | ||

| Liver | 91 | 58.0 |

| Lung | 62 | 39.5 |

| Lymph node | 50 | 31.8 |

| Peritoneum | 33 | 21.0 |

| Others* | 20 | 12.7 |

| Sum of metastasis | ||

| 1 organ metastasis, excluding peritoneum | 65 | 41.4 |

| 2 or more organ metastasis, excluding peritoneum | 59 | 37.6 |

| Any number of organs plus peritoneum | 33 | 21.0 |

| RAS mutation | ||

| Wild | 74 | 47.1 |

| Mutant | 83 | 52.9 |

| BRAF mutation | ||

| Wild | 142 | 90.4 |

| Mutant | 8 | 5.1 |

| Unknown | 7 | 4.5 |

| Previous systemic treatment lines | ||

| 2 | 85 | 54.1 |

| ≥ 3 | 72 | 45.9 |

| Time from first diagnosis of metastatic disease to treatment | ||

| < 24 months | 74 | 47.1 |

| ≥ 24 months | 83 | 52.9 |

| Previous targeted agents | ||

| RAS/RAF wild-type (n = 70) | ||

| Prior bevacizumab and cetuximab | 19 | 12.1 |

| Prior bevacizumab | 1 | 0.1 |

| Prior cetuximab | 32 | 20.4 |

| RAS or RAF mutated (n = 87) | ||

| Prior bevacizumab | 36 | 22.9 |

| Previous chemotherapy | ||

| Fluoropyrimidine | ||

| Refractory | 157 | 100 |

| Intolerant | 0 | 0 |

| Oxaliplatin | ||

| Refractory | 149 | 96.1 |

| Intolerant | 4 | 2.5 |

| Irinotecan | ||

| Refractory | 156 | 99.4 |

| Intolerant | 1 | 0.6 |

*Ovary 4%, bone 8%, etc., 4%.

W/D well differentiated, M/D moderately differentiated, P/D poorly differentiated, MSI microsatellite instability, MSS microsatellite stable. VEGF vascular endothelial growth factor, EGFR epidermal growth factor receptor.

FOLFOX; FU, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin, FOLFIRI; fluorouracil (FU), leucovorin, and irinotecan.

Among the 87 patients who were RAS or BRAF mutant, 36 (41.4%) were administered bevacizumab before treatment. Fifty-six (35.7%) of the 157 patients did not receive bevacizumab as their first- or second-line treatment and 8 (5.1%) were already exposed to capecitabine before the study treatment. The treatment exposures of the patients are summarised in Table 2. Patients received a median of six cycles of bevacizumab and capecitabine.

Table 2.

Treatment exposure (safety population).

| Total number of cycles administered (median), [range], [IQR] | 1,079 (6) [Range, 1–31], [IQR 3–9] |

|---|---|

| Cycles with delayed schedule | 33(3.1%) |

| Cycles with dose modification were made | |

| Capecitabine | 776 (71.9%) |

| Bevacizumab | 10(0.9%) |

| Relative dose intensity, median (%), [range], [IQR] | |

| Capecitabine (twice per day, mg/m2) | 80.2% (1,003 mg/m2 [Range, 778.4–1282.1], [IQR 926.5–1227] |

| Bevacizumab (mg/kg) | 100% (7.5 mg/kg) [Range, 5.0–7.5], [IQR 7.5–7.5] |

The median dose intensities of capecitabine and bevacizumab were 80.2% (1,003 mg/m2 PO twice daily, interquartile range [IQR], 74.1%–98.2%) and 100% (7.5 mg/kg, IQR, 100%–100%), respectively. A total of l079 cycles of treatment were administered, including 776 (71.9%) and 10 (0.9%) cycles with dose modifications made for capecitabine and bevacizumab, respectively. The median follow-up duration was 7.9 (IQR, 4.3–15.1) months.

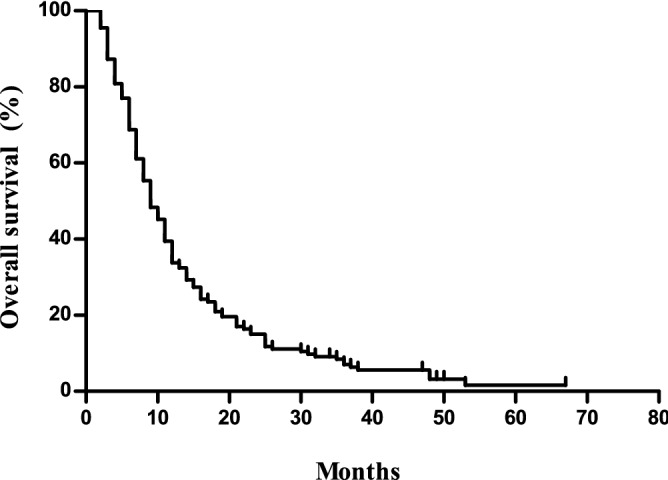

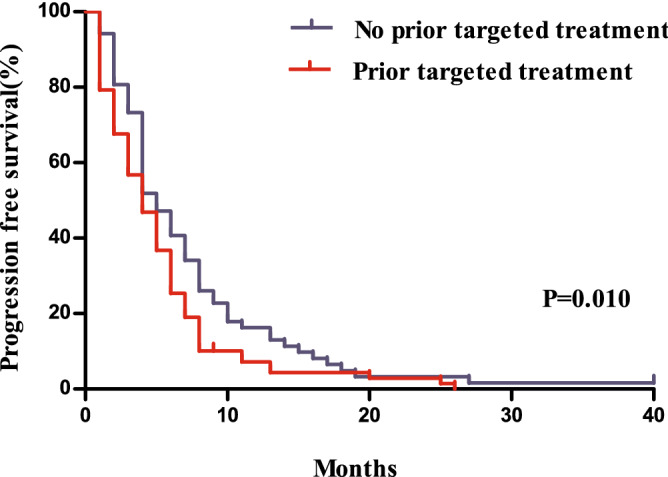

Response to treatment and survival

The median PFS was 4.6 (95% confidence interval [CI] 3.9–5.3) months, and the median OS was 9.7 (95% CI 8.3–11.1) months (Figs. 1 and 2). The overall response rate (ORR) was 14.0% with 22 (14.0%), 83 (52.9%), and 43 (27.4%) patients showing partial responses, stable disease, and progressive disease, respectively, based on the intent-to-treat analysis. The response was not evaluated in nine patients (5.7%). Table 3 summarises the univariable and multivariable analysis of the PFS and OS.

Figure 1.

Progression free survival of the study cohort.

Figure 2.

Overall Survival of the study cohort.

Table 3.

Multivariable analysis using the Cox regression model for survival outcomes.

| PFS | OS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude | Adjusted* | Crude | Adjusted** | |||||

| HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Age, years | ||||||||

| < 65 (n = 116) | Reference | 0.926 | Reference | 0.315 | ||||

| ≥ 65 (n = 41) | 0.99 (0.82–1.19) | 1.21 (0.84–1.74) | ||||||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male (n = 85) | Reference | 0.148 | Reference | 0.025 | Reference | 0.519 | ||

| Female (n = 72) | 0.78 (0.56 –1.10) | 0.67 (0.48 –0.95) | 0.90 (0.65–1.24) | |||||

| Primary site | ||||||||

| Rt. colon (n = 42) | Reference | 0.079 | Reference | 0.214 | Reference | 0.126 | Reference | 0.147 |

| Lt. colon (n = 115) | 1.40 (0.96–2.04) | 1.27 (0.87–1.87) | 1.33 (0.92–1.92) | 1.33 (0.90–1.96) | ||||

| Previous treatment lines | ||||||||

| 2 (n = 84) | Reference | 0.133 | Reference | 0.328 | Reference | 0.212 | ||

| ≥ 3 (n = 73) | 1.29 (0.93–1.79) | 1.20 (0.83–1.75) | 1.23 (0.89–1.70) | |||||

| RAS mutation | ||||||||

| Wild (n = 74) | Reference | 0.015 | Reference | 0.125 | Reference | 0.011 | Reference | 0.594 |

| Mutant (n = 83) | 0.66 (0.47–0.91) | 0.75 (0.51–1.09) | 0.66 (0.48–0.91) | 0.77 (0.55–1.09) | ||||

| Previous targeted biological treatment | ||||||||

| Yes (n = 87) | Reference | 0.011 | Reference | 0.004 | Reference | 0.002 | Reference | 0.002 |

| No (n = 70) | 0.65 (1.10–2.14) | 0.61 (0.43–0.85) | 0.59 (0.42–0.82) | 0.59 (0.43–0.82) | ||||

| Time from first diagnosis of metastatic disease to treatment | ||||||||

| < 24 months (n = 74) | Reference | 0.043 | Reference | 0.018 | Reference | 0.154 | Reference | 0.103 |

| ≥ 24 months (n = 83) | 0.71 (0.51–0.99) | 0.67 (0.48–0.93) | 0.79 (0.57–1.09) | 0.76 (0.55–1.06) | ||||

*Adjusted for sex, primary site, prior chemotherapy lines, RAS mutation, prior history of targeted agents, and time from diagnosis of metastatic disease to treatment.

**Adjusted for primary site, RAS mutation, prior history of targeted agents, and time from diagnosis of metastatic disease to treatment.

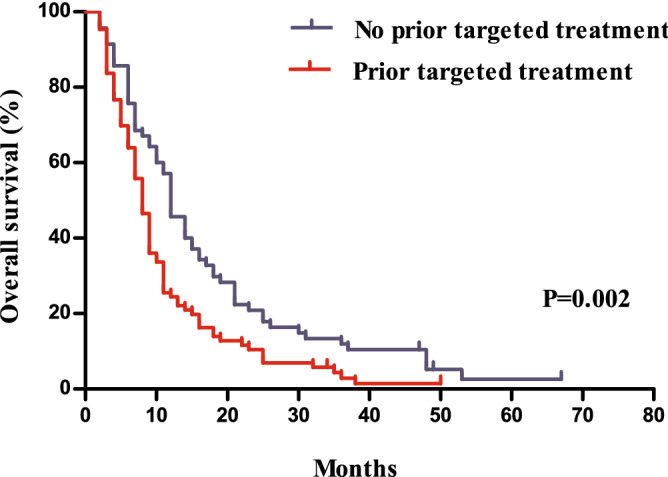

After the multivariable analysis, female sex (hazard ratio [HR], 0.67; 95% CI 0.48–0.95; P = 0.025), no prior history of targeted biologic treatment (HR, 0.61; 95% CI 0.43–0.85; P = 0.004), the interval between first diagnosis of metastatic disease to treatment (≥ 24 months; HR, 0.71; 95% CI 0.48–0.93; P = 0.018) were significantly associated with a longer PFS. Only no prior history of treatment with targeted agents was associated with a longer OS (HR, 0.59; 95% CI 0.43–0.82, P = 0.002).

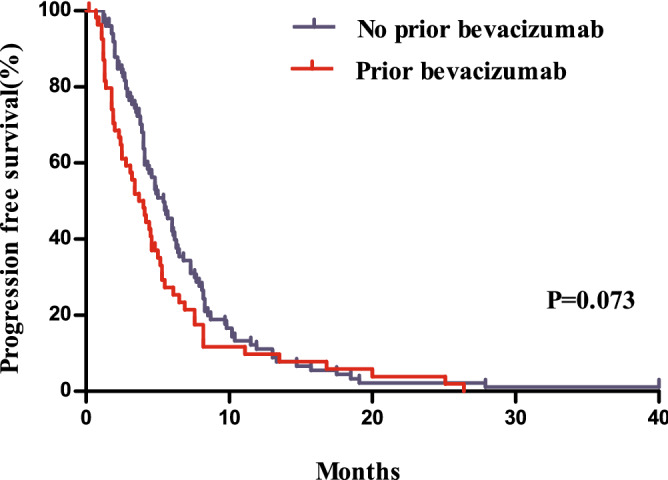

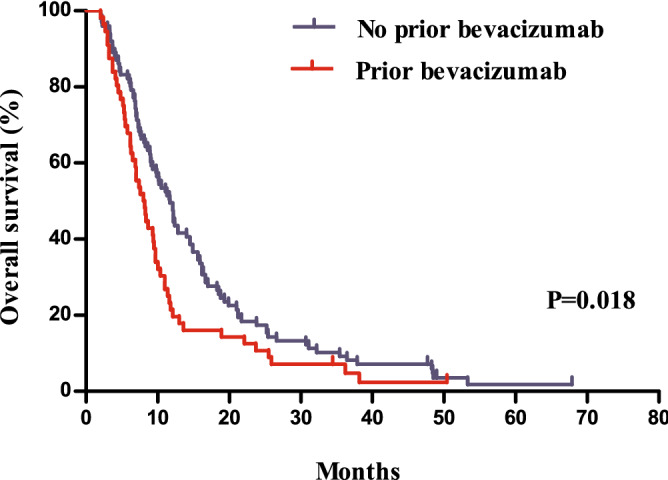

Compared to patients with a prior history of receiving targeted agents, those without showed a significantly longer PFS (P = 0.010, median 5.0 months vs. 4.1 months) and OS (P = 0.002, median 12.2 months vs. 8.2 months, Figs. 3 and 4). Patients without a history of treatment with bevacizumab showed PFS that was not significantly different from that of patients with a history of bevacizumab treatment (P = 0.073, 5.4 months vs. 4.0 months), whereas they showed a better ORR (one-sided P = 0.015, 19 [18.8%] vs. 3 [5.4%]) and significantly longer OS (P = 0.018, 11.7 months vs. 8.0 months, Figs. 5 and 6).

Figure 3.

Comparison of progression free survivals between patients with and without a history of the administration of targeted agents.

Figure 4.

Comparison of overall survivals between patients with and without a history of the administration of targeted agents.

Figure 5.

Comparison of progression free survivals between patients with and without a history of bevacizumab treatment.

Figure 6.

Comparison of overall survivals between patients with and without a history of bevacizumab treatment.

Safety profile of co-treatment with bevacizumab and capecitabine

The incidence of adverse events following co-treatment with bevacizumab and capecitabine is summarised in Table 4. The most common toxicity symptom was hand-foot syndrome (58.6%) and approximately 5% of patients showed a grade 3 level. Ten (6.4%) and 11 (7.0%) patients showed proteinuria and bleeding events, respectively. Moreover, there was no thromboembolic events among the patients. Notably, 14 patients had to stop chemotherapy because of toxicity, 2 discontinued because of bleeding events, 3 had severe proteinuria, 1 experiences perforation of the bowel, and 8 refused chemotherapy because of poor tolerance.

Table 4.

Adverse event after bevacizumab/capecitabine treatment.

| Adverse events | Any grade | Grade 3 or 4 |

|---|---|---|

| Any event | 157 (100%) | 28 (17.8%) |

| Hand foot syndrome | 92 (58.6%) | 8 (5.1%) |

| Fatigue | 24 (15.3%) | 2 (1.3%) |

| Nausea | 14 (8.9%) | 4 (2.6%) |

| Vomiting | 8 (5.1%) | 3 (1.9%) |

| Mucositis | 35 (22.3%) | 2 (1.3%) |

| Diarrhoea | 16 (10.2%) | 1 (0.6%) |

| Neutropenia | 39 (24.8%) | 5 (3.2%) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 54 (34.4%) | 2 (1.3%) |

| Anaemia | 96 (61.1%) | 2 (1.3%) |

| LFT elevation | 76 (48.4%) | 2 (1.3%) |

| Bilirubin elevation | 64 (40.8%) | 5 (3.2%) |

| Proteinuria | 10 (6.4%) | 3 (1.9%) |

| Bleeding/haemorrhage | 11 (7.0%) | 2 (1.3%) |

| Gastrointestinal perforation | 1 (0.6%) | 1 (0.6%) |

| Thromboembolic event | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

Discussion

In this study, co-treatment with bevacizumab and capecitabine in patients with mCRC refractory to at least two chemotherapy regimens showed efficacy with a 65% disease control rate, including a 14% PR, whereas the PFS and OS after treatment were 4.6 months and 9.7 months, respectively. This result indicted that the efficacy and treatment outcomes were comparable to those of previous studies16–18,24.

A previous study evaluating the efficacy of single-agent capecitabine in 5-FU resistant mCRC did not show a significant clinical benefit25. However, another study that assessed the effectiveness of co-treatment with bevacizumab and capecitabine after second-line treatment in 34 mCRC patients showed efficacy with disease control in most patients, with partial responses and stable disease in 3 (9%) and 21 (62%) patients, respectively. The median PFS and OS were 5.4 months and 12.2 months, respectively. Only hypertension was a common grade > 2 toxicity (24%), and none of the patients developed grade 3 or 4 bleeding, thrombosis, or intestinal perforation26. Although this study was small-sized, the results showed better survival benefits than those shown by other third-line data, with less toxicity. In our research, more patients with mCRC were included and they showed similar response rates and toxicities. Despite the shorter median OS and PFS, our results still showed comparable survival benefits with those of other third-line studies.

Co-treatment with new fluoropyrimidine and bevacizumab was also effective in refractory mCRC patients in recent studies. In a real-world study of TAS-102 with or without bevacizumab treatment in 57 refractory mCRC patients, co-treatment showed longer survival, with an OS of 14.4 months in the TAS-102 plus bevacizumab group and 6.1 months in the TAS-102 monotherapy group (HR, 0.33; 95% CI 0.15–0.73; P = 0.00627. Furthermore, a recent phase 2 randomised controlled study showed that co-treatment with TAS-102 and bevacizumab was associated with clinically relevant significantly longer survival than TAS-102 monotherapy without increased toxicity; The OS was 9.4 months and 6.7 months in the TAS-102 plus bevacizumab and TAS-102 monotherapy groups (HR, 0.55; 95% CI 0.32–0.94; P = 0.02823.

Regorafenib or TAS-102 showed high frequency of toxicity in previous studies. For regorafenib, 54% of patients showed ≥ grade 3 adverse events (16% hand-foot reaction, 11% hypertension) in the CONCUR study17. TAS 102 also induced grade 3 adverse events in 45.8% of patients in the TERRA study28. Compared to these agents, co-treatment with bevacizumab and capecitabine showed fewer incidences of ≥ grade 3 adverse events in our study. Specifically, 28 (17.8%) patients showed ≥ grade 3 adverse events and 14 (8.9%) had to stop chemotherapy because of the adverse events. Although our study was retrospective, co-treatment with bevacizumab and capecitabine could be a tolerable treatment option.

Recently, TASCO study compared the TAS-102 plus bevacizumab with capecitabine plus bevacizumab as the first-line treatment for patients with mCRC ineligible for intensive therapy. Although there was no statistically significant difference, the TAS-102 plus bevacizumab showed better clinical outcomes compared to capecitabine with median PFS 9.2 and 7.8 months (HR, 0.71;95% CI 0.48–1.06) and median OS was 22.3 and 17.7 months (HR, 0.78; 95% CI 0.55–1.10) respectively. Though this study was targeting different treatment settings from our study, the TAS-102 plus bevacizumab is likely to be the superior regimen to capecitabine and bevacizumab. On the other hand, TAS-102 plus bevacizumab regimen showed more grade 3 hematologic events such as decreased neutrophil count than capecitabine plus bevacizumab (18% vs. 1%). Considering hematologic toxicity and accessibility of TAS-102, the combination of bevacizumab and capecitabine also could be a good later line option29,30.

This study has some limitations, such as the single-centre retrospective design, absence of a control group, and the sample size, which was too small to verify the effectiveness of treatment. Nevertheless, our research showed the therapeutic efficacy and tolerability of bevacizumab plus capecitabine beyond second-line treatment in mCRC patients who had two or more lines of chemotherapies. This was especially evident in patients who had not previously used targeted agents. We consider that the combination bevacizumab and capecitabine regimen could be a useful treatment option for patients who are refractory to later-line treatments in mCRC.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by a grant 2017-0274 from the Asan Institute for Life Sciences, Asan Medical Center, with support from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant no. HI18C2383).

Author contributions

Y.H.B., J.E.K., S.Y.K., K.P.K., T.W.K. and Y.S.H. made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work or the acquisition of data; Y.H.B., J.E.K. and J.S.L. contributed to the statistical analysis or the interpretation of data. Y.H.B., J.E.K., T.W.K. and Y.S.H. have drafted the manuscript or substantively revised it; all authors have approved the submitted version and agreed to the accountable for all aspects of the work.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Yeong Hak Bang and Jeong Eun Kim.

References

- 1.Jung KW, Won YJ, Kong HJ, Lee ES. Prediction of cancer incidence and mortality in Korea. Cancer Res. Treat. Off. J. Korean Cancer Assoc. 2018;50(2):317–323. doi: 10.4143/crt.2018.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abbosh C, Birkbak NJ, Wilson GA, Jamal-Hanjani M, Constantin T, Salari R, et al. Phylogenetic ctDNA analysis depicts early-stage lung cancer evolution. Nature. 2017;545(7655):446–451. doi: 10.1038/nature22364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Venook AP, Niedzwiecki D, Lenz H-J, Innocenti F, Fruth B, Meyerhardt JA, et al. Effect of first-line chemotherapy combined with cetuximab or bevacizumab on overall survival in patients with KRAS wild-type advanced or metastatic colorectal cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317(23):2392–2401. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.7105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tabernero J, Takayuki Y, Cohn AL. Ramucirumab versus placebo in combination with second-line FOLFIRI in patients with metastatic colorectal carcinoma that progressed during or after first-line therapy with bevacizumab, oxaliplatin, and a fluoropyrimidine (RAISE): a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(6):e262. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(15)70273-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Cutsem E, Tabernero J, Lakomy R, Prenen H, Prausová J, Macarulla T, et al. Addition of aflibercept to fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan improves survival in a phase III randomized trial in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer previously treated with an oxaliplatin-based regimen. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012;30(28):3499–3506. doi: 10.1200/jco.2012.42.8201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bennouna J, Sastre J, Arnold D, Österlund P, Greil R, Van Cutsem E, et al. Continuation of bevacizumab after first progression in metastatic colorectal cancer (ML18147): a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(1):29–37. Epub 2012/11/22. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(12)70477-1. PubMed PMID: 23168366. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Douillard JY, Oliner KS, Siena S, Tabernero J, Burkes R, Barugel M, et al. Panitumumab-FOLFOX4 treatment and RAS mutations in colorectal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369(11):1023–1034. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwartzberg LS, Rivera F, Karthaus M, Fasola G, Canon JL, Hecht JR, et al. PEAK: a randomized, multicenter phase II study of panitumumab plus modified fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (mFOLFOX6) or bevacizumab plus mFOLFOX6 in patients with previously untreated, unresectable, wild-type KRAS exon 2 metastatic colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014;32(21):2240–2247. doi: 10.1200/jco.2013.53.2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sartore-Bianchi A, Trusolino L, Martino C, Bencardino K, Lonardi S, Bergamo F, et al. Dual-targeted therapy with trastuzumab and lapatinib in treatment-refractory, KRAS codon 12/13 wild-type, HER2-positive metastatic colorectal cancer (HERACLES): a proof-of-concept, multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(6):738–746. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(16)00150-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drilon A, Laetsch TW, Kummar S, DuBois SG, Lassen UN, Demetri GD, et al. Efficacy of larotrectinib in TRK fusion-positive cancers in adults and children. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018;378(8):731–739. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1714448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hong DS, Morris VK, El Osta B, Sorokin AV, Janku F, Fu S, et al. Phase IB study of vemurafenib in combination with irinotecan and cetuximab in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer with BRAFV600E mutation. Cancer Discov. 2016;6(12):1352–1365. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.Cd-16-0050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kopetz S, Grothey A, Yaeger R, Van Cutsem E, Desai J, Yoshino T, et al. Encorafenib, binimetinib, and cetuximab in BRAF V600E–mutated colorectal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019;381(17):1632–1643. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1908075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, Bartlett BR, Kemberling H, Eyring AD, et al. PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372(26):2509–2520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Overman MJ, McDermott R, Leach JL, Lonardi S, Lenz HJ, Morse MA, et al. Nivolumab in patients with metastatic DNA mismatch repair-deficient or microsatellite instability-high colorectal cancer (CheckMate 142): an open-label, multicentre, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(9):1182–1191. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(17)30422-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Le DT, Kim TW, Cutsem EV, Geva R, Jäger D, Hara H, et al. Phase II open-label study of pembrolizumab in treatment-refractory, microsatellite instability–high/mismatch repair-deficient metastatic colorectal cancer: KEYNOTE-164. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020;38(1):11–19. doi: 10.1200/jco.19.02107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grothey A, Van Cutsem E, Sobrero A, Siena S, Falcone A, Ychou M, et al. Regorafenib monotherapy for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer (CORRECT): an international, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9863):303–312. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)61900-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li J, Qin S, Xu R, Yau TC, Ma B, Pan H, et al. Regorafenib plus best supportive care versus placebo plus best supportive care in Asian patients with previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer (CONCUR): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(6):619–629. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(15)70156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mayer RJ, Van Cutsem E, Falcone A, Yoshino T, Garcia-Carbonero R, Mizunuma N, et al. Randomized trial of TAS-102 for refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372(20):1909–1919. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee JJ, Kim TM, Yu SJ, Kim DW, Joh YH, Oh DY, et al. Single-agent capecitabine in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer refractory to 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin chemotherapy. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004;34(7):400–404. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyh068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen HX, Mooney M, Boron M, Vena D, Mosby K, Grochow L, et al. Phase II multicenter trial of bevacizumab plus fluorouracil and leucovorin in patients with advanced refractory colorectal cancer: an NCI Treatment Referral Center Trial TRC-0301. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006;24(21):3354–3360. doi: 10.1200/jco.2005.05.1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koeberle D, Kollar A, Saletti P, Roth A, Frueh M, Popescu RA, et al. Bevacizumab continuation versus no continuation after first-line chemotherapy plus bevacizumab in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: a randomized phase III non-inferiority trial (SAKK 41/06) Ann. Oncol. 2015;26(4):709–714. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kang BW, Kim TW, Lee JL, Ryu MH, Chang HM, Yu CS, et al. Bevacizumab plus FOLFIRI or FOLFOX as third-line or later treatment in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer after failure of 5-fluorouracil, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin: a retrospective analysis. Med. Oncol. 2009;26(1):32–37. doi: 10.1007/s12032-008-9077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pfeiffer P, Yilmaz M, Möller S, Zitnjak D, Krogh M, Petersen LN, et al. TAS-102 with or without bevacizumab in patients with chemorefractory metastatic colorectal cancer: an investigator-initiated, open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(3):412–420. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(19)30827-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Cutsem E, Yoshino T, Lenz HJ, Lonardi S, Falcone A, Limón ML, et al. Nintedanib for the treatment of patients with refractory metastatic colorectal cancer (LUME-Colon 1): a phase III, international, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Ann. Oncol. 2018;29(9):1955–1963. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoff PM, Pazdur R, Lassere Y, Carter S, Samid D, Polito D, et al. Phase II study of capecitabine in patients with fluorouracil-resistant metastatic colorectal carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004;22(11):2078–2083. doi: 10.1200/jco.2004.05.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larsen FO, Boisen MK, Fromm AL, Jensen BV. Capecitabine and bevacizumab in heavily pre-treated patients with advanced colorectal cancer. Acta Oncol. 2012;51(2):231–233. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2011.614637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fujii H, Matsuhashi N, Kitahora M, Takahashi T, Hirose C, Iihara H, et al. Bevacizumab in combination with TAS-102 improves clinical outcomes in patients with refractory metastatic colorectal cancer: a retrospective study. Oncologist. 2019 doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu J, Kim TW, Shen L, Sriuranpong V, Pan H, Xu R, et al. Results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial of trifluridine/tipiracil (TAS-102) monotherapy in asian patients with previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer: the TERRA Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018;36(4):350–358. doi: 10.1200/jco.2017.74.3245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Cutsem E, Danielewicz I, Saunders MP, Pfeiffer P, Argilés G, Borg C, et al. Trifluridine/tipiracil plus bevacizumab in patients with untreated metastatic colorectal cancer ineligible for intensive therapy: the randomized TASCO1 study✰. Ann. Oncol. 2020;31(9):1160–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cutsem EV, Danielewicz I, Saunders MP, Pfeiffer P, Argiles G, Borg C, et al. Phase II study evaluating trifluridine/tipiracil + bevacizumab and capecitabine + bevacizumab in first-line unresectable metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) patients who are noneligible for intensive therapy (TASCO1): results of the final analysis on the overall survival. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021;39(3):14. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2021.39.3_suppl.14. [DOI] [Google Scholar]