Abstract

Objective:

Poor sleep quality is related to worse neurocognition in older adults and in people with HIV (PWH); however, many previous studies have relied only on self-report sleep questionnaires, which are inconsistently correlated with objective sleep measures. We examined relationships between objective and subjective sleep quality and neurocognition in persons with and without HIV, aged 50 and older.

Method:

Eighty-five adults (PWH n=52, HIV-negative n=32) completed comprehensive neuropsychological testing to assess global and domain-specific neurocognition. Objective sleep quality was assessed with wrist actigraphy (total sleep time, efficiency, sleep fragmentation) for five to 14 nights. Subjective sleep quality was assessed with the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index.

Results:

Objective and subjective sleep measures were unrelated (p’s>0.30). Compared to HIV-negative participants, PWH had greater sleep efficiency (80% vs. 75%, p=0.05) and were more likely to be using prescription and/or over the counter sleep medication (p=0.04). In the whole sample, better sleep efficiency (p<0.01) and greater total sleep time (p=0.05) were associated with better learning. Less sleep fragmentation was associated with better learning (p<0.01) and recall (p=0.04). While PWH had slightly stronger relationships between total sleep time and sleep fragmentation, it is not clear if these differences are clinically meaningful. Better subjective sleep quality was associated with better executive function (p<0.01) and working memory (p=0.05); this relationship was primarily driven by the HIV-negative group.

Conclusions:

Objective sleep quality was associated with learning and recall whereas subjective sleep quality was associated with executive function and working memory. Therefore, assessing objective and subjective sleep quality could be clinically useful, as they are both related to important domains of cognition frequently impacted in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders as well as neurodegenerative disorders associated with aging. Future studies should evaluate if behavioral sleep interventions can improve neurocognition.

Keywords: health behavior, sleep hygiene, neuropsychology, actigraphy, aging, digital health, real-world evidence, executive functioning, memory

Introduction

The availability of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) has greatly improved life expectancy among persons with HIV (PWH) who have access to adequate health care (Samji et al., 2013). Despite the beneficial effects of cART on controlling HIV viremia, neurocognitive impairment remains prevalent among PWH, particularly in PWH aged 50 and older (Cherner et al., 2004; Makinson et al., 2019). However, recent studies demonstrate that some PWH are able to achieve successful cognitive aging (i.e., generally defined as preserved cogntion and everyday functioning; Malaspina et al., 2011; Moore et al., 2017; Moore et al., 2014). Therefore, as the population of older PWH continues to grow, there is an important need to identify predictive markers of neurocognitive impairment and investigate potentially modifiable health-related behaviors that may promote successful cognitive aging among older PWH.

The prevalence of sleep disturbance is elevated in both PWH (58%; Wu, Wu, Lu, Guo, & Li, 2015) and older HIV-negative adults (14–38%; Morin, LeBlanc, Daley, Gregoire, & Merette, 2006; Ohayon, 2002) in comparison to the general population (10%; Ram, Seirawan, Kumar, & Clark, 2010). In PWH, sleep disturbance is hypothesized to be a multidetermined result of the neurotoxic cascade initiated by HIV (e.g., inflammation), antiretroviral medications, and psychosocial variables (e.g., depression, stress; Allavena et al., 2016; Gallego et al., 2004; Vosvick et al., 2004; Wirth et al., 2015). In the geriatric literature, studies suggest sleep quality decreases as a result of normal aging and more profound sleep disturbances are associated with age-related neurodegenerative disorders (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease; Crowley, 2011). Alzheimer’s disease pathology (i.e., p-tau) has also been shown to target wake-promoting neurons in the brain, which has been hypothesized to account for the sleep-wake disruption seen in patients with Alzheimer’s disease (i.e., increased sleep fragmentation, arousal deficiencies; Oh et al., 2019; Peter-Derex, Yammine, Bastuji, & Croisile, 2015). Moreover, it is hypothesized that sleep may promote cognition by supporting proper glymphatic function to clear neurotoxins from the brain (Eugene & Masiak, 2015; Fultz et al., 2019), and poor sleep may contribute to neurodegeneration through increased neuroinflammation and disrupted neurogenesis in the hippocampus (Yaffe, Falvey, & Hoang, 2014). Taken together, because HIV is associated with chronic neuroinflammation and accelerated brain aging (Wing, 2016), sleep may be particularly important as PWH age to help preserve brain integrity and cognition.

Although there are increased rates of cognitive impairment and poor sleep quality among PWH, the association between sleep quality and cognition in this population remains relatively understudied. In a study of 36 adults with HIV on ART, Gamaldo et al. (2013) found that some tests of attention, executive function, and motor speed were associated with better sleep quality on polysomnography in PWH; however, subjective sleep quality and actigraphy-based sleep indices were not significantly related to cognitive functioning. In another study, researchers found that worse subjective sleep quality was associated with worse learning and delayed recall among PWH and HIV-negative adults (Mahmood, Hammond, Nunez, Irwin, & Thames, 2018). Notably, this study has been the only study thus far to compare PWH and HIV-negative adults, but only examined subjective sleep quality. While these studies present somewhat variable results, they suggest that sleep quality is associated with cognitive function among PWH and highlight the need to better understand the relationships between sleep and cognition in this population.

In the cognitive aging literature, research findings on the relationship between sleep and cognition are also somewhat heterogeneous but several studies have found subjective and/or objective measures of sleep disturbance are related to worse cognitive functioning and increased risk of cognitive impairment (Shi et al., 2018; Yaffe et al., 2014). Given the increased rates of sleep disturbance in PWH and older adults, sleep may be an important health behavior that can be modified in order to decrease the risk of HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Disorders (HAND; Antinori et al., 2007) and/or age-related cognitive decline.

Sleep quality is a complex construct to empirically evaluate. Currently, most research utilizes self-report sleep questionnaires or polysomnography (current “gold standard” assessment of sleep), which have limitations. Questionnaires rely on retrospective recall that can be highly variable and biased as a subjective report. Polysomnography monitors sleep stages and cycles to identify disruptive sleep patterns; however, polysomnography is typically captured in a controlled setting for one to two nights, rather than in an individual’s regular sleep environment. With the advancement of wearable digital technology, passive data collection methods have the ability to capture objective sleep measures in real-time and in an individual’s natural sleeping environment for multiple days. Preliminary evidence optimistically suggests wrist-worn actigraphy can be efficacious in assessing sleep variables about which participants lack insight (e.g., wake after sleep onset; Lee & Suen, 2017). For example, in a study aimed to understand specific sleep problems among adults with HIV, participants who reported difficulty falling asleep and subjective sleep disturbances had actigraphy and clinical measures comparable to those of the good sleepers (Lee et al., 2012). Similarly, a study of HIV-negative adults aged 55 and older found that perceived sleep quality, measured with the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), was different from and did not correlate with objective sleep quality; the authors hypothesize this may be in part due to the reliance on retrospective recall on subjective measures which may be particularly difficult for older adults. Therefore, the authors concluded that objective and subjective sleep quality measures tap different aspects of sleep and both yield clinically meaningful data (Landry, Best, & Liu-Ambrose, 2015). Thus, implementing both subjective and objective sleep measurement techniques in research designs may provide additional insight into the differential patterns of sleep quality among older persons living with and without HIV.

Given that PWH often experience poor sleep quality, sleep may be an important modifiable health behavior to address in order to promote successful cognitive aging. Thus, our primary study aim was to fill important gaps in the literature by examining the relationships between neurocognition, subjective sleep quality, and objective sleep quality, and explore if these relationships differ by HIV serostatus. We hypothesized that both subjective and objective sleep quality would be associated with neurocognition; however, due to the mixed results in the literature described above, we did not have a priori hypotheses about which specific cognitive domains would be related to sleep quality. Our secondary aim was to characterize subjective and objective sleep quality measures in middle-aged and older adults with and without HIV.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Fifty-two PWH and 32 HIV-negative adults, aged 50 to 74 years, were included in this cross-sectional, observational study. Participants were recruited from an existing subject pool at University of California San Diego’s (UCSD) HIV Neurobehavioral Research Program (HNRP) and newly recruited from the community (e.g., community clinics, flyers in the community, presentations at community organizations) between 2016 and 2018. If a participant was co-enrolled in another study at the HNRP and completed a comprehensive neuromedical and neurobehavioral visit for the co-enrolled study within the past six months, their data from these visits were linked. The study’s exclusion criteria were: serious mental illness (e.g., bipolar disorder, schizophrenia), history of a non-HIV neurological disorder (e.g., head injury with loss of consciousness >30 minutes, seizure disorder, stroke), persons not fluent in English, and estimated verbal IQ < 70 as measured by the Wide-Range Achievement Test-4 Reading Subtest. Additionally, participants were rescheduled if they had a positive alcohol breathalyzer or urine toxicology (which screend for marijuana, cocaine, amphetamines, opiates, barbituates, benzodiazepines, PCP; participants with prescription medications in these drug classes were not considered to be “positive”) with the exception of marijuana, given its long duration of detection. Participants with positive urine toxicology for marijuana denied marijuana use on the day of testing, and participants that were positive for marijuana or prescription medications on the urine toxicology test gave no evidence of intoxication during neuromedical or neuropsychological evaluations. Participants were excluded from analyses if they had less than five days of actigraphy sleep data (n=2). The study was approved by the UCSD Institutional Review Board. Additionally, all participants demonstrated decisional capacity (Jeste et al., 2007), provided written informed consent, and were compensated for their participation.

Measures and Procedures

Neuropsychological Evaluation.

Participants completed the standard HNRP neuropsychological test battery that assesses seven cognitive domains (i.e., verbal fluency, executive function, speed of information processing, verbal and visual learning, delayed recall memory, attention/working memory, and complex motor skills) commonly affected in HIV (Heaton et al., 2010). Specific tests in each domain can be found in Table 1. Raw scores from the neuropsychological tests are converted to practice-effect corrected, normalized scaled scores and averaged per domain to get an overall domain scaled score (M = 10, SD = 3; Cysique et al., 2011). Additionally, estimated premorbid IQ was measured using the WRAT-4 Reading subtest.

Table 1.

Neuropsychological Battery by Domain

| Verbal Fluency | Learning |

| Controlled Oral Word Association Test (FAS; Benton, Hamsher, & Sivan, 1994) | Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised (Total Learning; Brandt & Benedict, 2001) |

| Category Fluency Test (“animals” and “actions”; Benton et al., 1994) | Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-Revised (Total Learning; Benedict, 1997) |

| Executive Function | Recall |

| Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (Computerized 64-cards; Kongs, Thompson, Iverson, & Heaton, 2000) | Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised (Delayed Recall; Brandt & Benedict, 2001) |

| Trail Making Test Part B (Army Individual Test Battery, 1944) | Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-Revised (Delayed Recall; Benedict, 1997) |

| Stroop Color and Word Test (Interference score; Golden & Freshwater, 1978) | Working Memory |

| Speed of Information Processing | WAIS-III Letter-Number Sequencing (Psychological Corporation, 1997) |

| WAIS-III Digit Symbol (Psychological Corporation, 1997) | Paced Auditory Serial Addition Task (Gronwall, 1977) |

| WAIS-III Symbol Search (Psychological Corporation, 1997) | Complex Motor Skills |

| Trail Making Test Part A (Army Individual Test Battery, 1944) | Grooved Pegboard Test (Dominant and Non-Dominant; Kløve, 1963) |

| Stroop Color and Word Test (color trial; Golden & Freshwater, 1978) |

Note. WAIS-III = Weschler Adult Intelligence Scale – Third Edition

Objective Sleep.

Participants were asked to wear the ActiGraph GT9X Link device on their non-dominant wrist 24 hours/day for the duration of a two-week study (range of sleep data: 5–15 nights), except when the watch could get wet (e.g., bathing). The ActiGraph has been shown to be able to distinguish between sleep and wakefulness when worn during sleep (Cole, Kripke, Gruen, Mullaney, & Gillin, 1992), and the time windows were assessed for sleep versus wake states on a minute-by-minute basis using a rolling window currently accepted as best practice (Cole et al., 1992; Sadeh, Sharkey, & Carskadon, 1994). Participants were also asked to record in daily written logs the time that they went to bed (i.e., tried to fall asleep) and the time that they first awoke in order to estimate number of minutes in bed. A trained research assistant matched the sleep and awake times reported by participants to the objective data to ensure the objective data also suggested that participant was likely asleep or trying to sleep. When sleep logs were missing, number of minutes in bed (i.e., sleep onset and awake time) were manually determined from the objective data by a trained research assistant using the detection methods detailed in Full et al. (2018). The following variables were derived and used in analyses in this study: total sleep time – number of minutes asleep derived from the Cole-Kripke algorithm; sleep efficiency – total sleep time divided by number of minutes in bed; and sleep fragmentation index – an index of restlessness during sleep (Knutson, Van Cauter, Zee, Liu, & Lauderdale, 2011; Loewen, Siemens, & Hanly, 2009).

Subjective Sleep (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index).

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI; Buysse, Reynolds, Monk, Berman, & Kupfer, 1989) is a widely-used, 19-item measure that assesses self-reported sleep quality over the past month. The PSQI yields seven component scores: daytime dysfunction, habitual sleep efficiency, subjective sleep quality, sleep disturbances, sleep duration, sleep latency, and use of sleeping medications. Each component score is summed to create a global PSQI score ranging from 0–21, with higher scores reflecting worse sleep quality.

Neuromedical & Psychiatric Assessment.

All participants completed a standardized neuromedical and psychiatric assessment. Medical comorbidities in Table 2 were determined by a combination of self-report diagnosis or use of a medication for the condition. BMI was calculated from height and weight measurements. Current and lifetime psychiatric and substance use diagnoses in Table 2 were assessed using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI; World Health Organization, 1997), which is a computer-assisted structured interview. Participants also completed the Beck Depression Inventory-II (Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996) and Beck Anxiety Inventory (Beck, Epstein, Brown, & Steer, 1988) to assess current depressive and anxiety symptoms.

Table 2.

Participant characteristics by HIV serostatus (N=84)

| HIV+ (n=52) |

HIV− (n=32) |

t or χ2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Variables | ||||

| Age (years), M (SD) | 59.1 (6.3) | 59.2 (6.7) | −0.2 | 0.88 |

| Male, n (%) | 44 (84.6%) | 18 (56.3%) | 8.2 | <0.01 |

| Race/Ethnicity | -- | -- | FET | 0.56 |

| Non-Hispanic White, n (%) | 33 (63.4%) | 21 (65.6%) | -- | -- |

| African American/Black, n (%) | 13 (25.0%) | 5 (15.6%) | -- | -- |

| Hispanic/Latino, n (%) | 4 (7.7%) | 5 (15.6%) | -- | -- |

| Other, n (%) | 2 (3.9%) | 1 (3.1%) | -- | -- |

| Education (years), M (SD) | 14.2 (2.5) | 14.8 (2.5) | −1.1 | 0.26 |

| Employed, n (%) | 16 (31.4%) | 11 (34.4%) | 0.1 | 0.78 |

| Household Incomea, n (%) | -- | -- | FET | 0.01 |

| <$10,000 | 7 (14.0%) | 3 (11.1%) | -- | -- |

| $10,000 – $34,999 | 36 (72.0%) | 11 (40.7%) | -- | -- |

| $35,000 –$74,999 | 3 (6.0%) | 6 (22.2%) | -- | -- |

| ≥$75,000 | 4 (8.0%) | 7 (25.9%) | -- | -- |

| Medical comorbidities | ||||

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 34 (65.4%) | 15 (46.9%) | 2.8 | 0.09 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 33 (63.5%) | 14 (43.8%) | 3.1 | 0.08 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 10 (19.2%) | 9 (28.1%) | 0.9 | 0.34 |

| Hepatitis C, n (%) | 16 (30.8%) | 2 (6.3%) | FET | 0.01 |

| BMIb, M (SD) | 27.9 (5.9) | 32.4 (8.9) | −2.5 | 0.01 |

| BMI >30b, n (%) | 14 (26.9%) | 15 (46.9%) | 3.5 | 0.06 |

| “At risk” for obstructive sleep apnea, n (%) | 9 (17%) | 9 (28%) | 1.4 | 0.241 |

| Psychiatric functioning | ||||

| LT MDD, n (%) | 37 (71.2%) | 9 (28.1%) | 14.8 | <0.01 |

| Current MDDb, n (%) | 7 (13.5%) | 1 (3.2%) | FET | 0.25 |

| LT any substance use disorder, n (%) | 37 (71.2%) | 16 (50.0%) | 3.8 | 0.06 |

| LT alcohol use disorder, n (%) | 27 (51.9%) | 11 (34.4%) | 2.5 | 0.12 |

| LT cannabis use disorder, n (%) | 21 (40.4%) | 6 (18.8%) | 4.3 | 0.04 |

| LT methamphetamine use disorder, n (%) | 18 (34.6%) | 4 (12.5%) | FET | 0.04 |

| Current substance use disorderb, c, n (%) | 2 (3.9%) | 1 (3.5%) | FET | 1.00 |

| BDI-II, median [IQR] | 7 [2, 11.75] | 3 [0, 4.75] | 8.8 | <0.01 |

| BAI, median [IQR] | 4 [1, 10.75] | 1 [0, 3.75] | 11.4 | <0.01 |

| HIV Characteristics | ||||

| AIDS, n (%) | 34 (65.3%) | -- | -- | -- |

| Current CD4, median [IQR] | 703 [577, 857] | -- | -- | -- |

| Nadir CD4, median [IQR] | 148 [41, 300] | -- | -- | -- |

| Duration of HIV infection (years), median [IQR] | 24.1 [18.4, 28.6] | -- | -- | -- |

| On ART, n (%) | 49 (94.2%) | -- | -- | -- |

| Undetectable viral loadd, n (%) | 47 (97.9%) | -- | -- | -- |

Note: BMI = body mass index; FET = Fisher’s Exact Test; LT = lifetime; MDD = major depressive disorder; BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory-II; BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory; ART = antiretroviral therapy

n=77;

n=83;

all current substance use disorder was cannabis use disorder;

n=48

Medications Used to Treat Sleep.

Participants were considered to be using sleep medications if they were prescribed a medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for insomnia (i.e., butabarbital, doxepin, estazolam, eszopiclone, flurazepam, quazepam, ramelteon, secobarbital, suvorexant, tasimelteon, temazepam, triazolam, zaleplon, and zolpidem), or trazodone, or over-the-counter insomnia drugs (i.e., diphenhydramine, doxylamine, and melatonin). Because the center does not routinely assess over-the-counter medications, participants were also considered to be using sleep medications if they reported using “medicine to help you sleep” at least “once or twice a week” or more on the PSQI.

Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) Risk Composite.

A diagnosis of OSA or OSA risk was not formally assessed in this study. However, given that OSA is associated with worse cognition (Bucks, Olaithe, & Eastwood, 2013), we attempted to account for OSA risk by creating an “at-risk” for OSA group based on known risk factors (i.e., BMI and hypertension; Young, Skatrud, & Peppard, 2004). Participants were dichotomized into an “at-risk” and “low risk” group and were classified as at-risk if they had both hypertension and a BMI greater than or equal to 30 kg/m2.

HIV Disease Characteristics.

The following were collected via self-report: AIDS diagnosis, antiretroviral therapy regimen, estimated duration of infection, and nadir CD4 count (unless current CD4 count was lower than reported nadir value). Viral load detectability (<50 copies/mL) and current CD4 count were measured in blood plasma. In all participants, HIV serostatus was confirmed with HIV/HCV antibody point-of-care rapid test and confirmatory Western blot analyses.

Statistical Analyses

In order to characterize the study sample, analyses examining HIV serostatus group differences on participant characteristics, sleep quality, and neurocognitive performance were assessed via Chi-Square, Fisher’s exact tests, and t-tests (or non-parametric equivalent), as appropriate. The relationship between objective sleep variables and subjective sleep quality (i.e., PSQI) were examined using Pearson correlations, and the relationship between anxiety and depression and sleep variables were examined using Spearman correlations.

Multivariable linear regression analyses were performed to examine whether objective and subjective sleep variables were associated with cognition. In order to adjust for known demographic influences on sleep and/or cognition, age, sex, years of education, and race/ethnicity (i.e., non-Hispanic White or other – African American, Hispanic/Latino, Asian, Native American) were included in the model. Unadjusted scaled scores (i.e., not adjusted for demographic variables) were used as the outcome variables, as demographics were included as covariates in the overall models. HIV serostatus, OSA risk, and use of sleep medications were included as covariates in the objective sleep analyses. Subjective sleep analyses included all covariates except for use of sleep medications as this is factored into total PSQI score. Subjective and objective sleep measures did not differ between those that were employed versus unemployed/retired (p’s>0.30), and, in paired T-tests, objective sleep measures did not differ by weekday versus weekend days (i.e., Friday and Saturday nights; p’s>0.50); therefore, employment status and proportion of weekend days were not included as covariates. For analyses that included the entire sample, we report which findings survive after adjusting for multiple comparisons using Bonferroni correction (0.05/4 sleep measures = 0.0125) in Table 3. Given the power limitations imposed by our modest sample size, we examined cognitive domains that were significantly related to sleep in the entire sample stratified by HIV serostatus. All analyses were conducted in JMP version 14.0.0 (SAS Institute, 2018).

Table 3.

Sleep and Cognitive Variables by HIV serostatus (N=84)

| HIV+ (n=52) |

HIV− (n=32) |

t or χ2 | p | Effect size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Objective Sleep Variables | |||||

| Number of days of sleep data, M (SD) | 12.3 (2.2) | 12.3 (2.4) | 0.2 | 0.854 | g = 0.02 |

| Efficiency, M (SD) | 79.5% (9.2) | 75.1% (10.3) | 2.0 | 0.048 | g = 0.45 |

| <85% Efficiency, n (%) | 40 (77%) | 25 (78%) | 0.0 | 0.898 | φ = 0.01 |

| Objective Total Sleep Time (hours), M (SD) | 5.9 (1.4) | 5.6 (1.1) | 1.0 | 0.336 | g = 0.23 |

| <7 hours Total Sleep Time, n (%) | 42 (81%) | 25 (78%) | 0.1 | 0.770 | φ = 0.03 |

| >9 hours Total Sleep Time, n (%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | FET | 0.999 | -- |

| Sleep Fragmentation Index, M (SD) | 35.0 (11.9) | 39.5 (13.0) | 1.6 | 0.116 | g = 0.36 |

| Subjective Sleep Variables | |||||

| PSQI Totala, M (SD) | 8.0 (4.0) | 6.2 (3.2) | 2.2 | 0.033 | g = 0.48 |

| PSQI Total excluding use of sleep medicationsa, M (SD) | 6.8 (3.4) | 5.6 (2.8) | 1.7 | 0.094 | g = 0.37 |

| >5 PSQI Totala, n (%) | 36 (71%) | 19 (59%) | 1.3 | 0.246 | φ = 0.12 |

| Subjective Total Sleep Timea, M (SD) | 6.9 (1.4) | 6.8 (1.2) | 0.4 | 0.704 | g = 0.07 |

| Using Sleep Medications, n (%) | 23 (44%) | 7 (22%) | 4.3 | 0.038 | φ = 0.23 |

| Cognitive Functioning | |||||

| Global SS, M (SD) | 8.7 (2.0) | 9.4 (1.9) | 1.5 | 0.144 | g = 0.35 |

| Verbal SS, M (SD) | 10.5 (2.6) | 11.4 (2.9) | 1.4 | 0.170 | g = 0.33 |

| Executive Function SS, M (SD) | 8.5 (2.5) | 9.0 (2.3) | 0.9 | 0.356 | g = 0.20 |

| SIP SS, M (SD) | 9.3 (2.3) | 10.3 (2.6) | 1.8 | 0.083 | g = 0.41 |

| Learning SS, M (SD) | 6.9 (2.7) | 7.5 (2.7) | 1.0 | 0.315 | g = 0.22 |

| Memory SS, M (SD) | 7.0 (2.5) | 7.8 (2.6) | 1.3 | 0.191 | g = 0.31 |

| Working Memory SS, M (SD) | 10.0 (2.8) | 10.1 (2.9) | 0.2 | 0.858 | g = 0.03 |

| Motor SS, M (SD) | 7.5 (2.7) | 8.0 (2.4) | 0.8 | 0.432 | g = 0.19 |

| Premorbid IQ (WRAT), M (SD) | 103 (14) | 106 (16) | 0.9 | 0.394 | g = 0.20 |

Note: FET = Fischer’s Exact Test; PSQI = Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; SS = scaled score; SIP = speed of information processing; WRAT = Wide Range Achievement Test – Reading Subtest. Effect size: g = Hedge’s g (0.2 = small, 0.5 = medium, 0.8 = large), φ = phi coefficient (0.1 = small, 0.3 = medium, 0.5 = large).

n=83

Results

Sample Characteristics

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 2. PWH and HIV-negative groups were fairly similar on demographic variables with the exception of sex (84.6% males in PWH group vs 56.3% males in HIV-negative group). PWH were more likely to have hepatitis C (p = 0.01) and lifetime Major Depressive Disorder (p < 0.01), and were somewhat more likely to have a lifetime substance use disorder (p = 0.06). PWH had greater current levels of depressed mood (i.e., Beck Depression Inventory-II; p < 0.01) and anxiety (i.e., Beck Anxiety Inventory; p < 0.01); however, average depression and anxiety scores for both groups were in the “minimal” range. The HIV-negative group had a greater body mass index (BMI; p = 0.01) than PWH. The two groups did not significantly differ on cognitive functioning or premorbid IQ, although effect sizes in some domains favored the HIV-negative group (e.g., global, speed of information processing, memory; see Table 3). With regard to HIV disease characteristics, PWH in this study had high rates of ART use (94.2%) and undetectable viral load (97.9%). Of note, analyses were re-run excluding the three PWH not on ART, and the results did not differ significantly.

Sleep Quality by HIV Serostatus

Sleep quality characteristics and cognitive functioning are presented in Table 3. PWH had a slightly greater average sleep efficiency (PWH: 79.5%, HIV-negative: 75.1%; p = 0.05). In follow-up analyses, after covarying for use of sleep medications, OSA risk, and sex, the HIV effect was somewhat attenuated and no longer significant (B = 3.1%, p = 0.20). Additionally, PWH were more likely to use sleep medications (PWH: 44%, HIV-negative: 22%; p = 0.04). PWH had a higher mean PSQI total score (PWH: 8.0, HIV-negative: 6.2, p = 0.03); however, this difference was somewhat attenuated when removing the sleep medication component from the PSQI (PWH: 6.8, HIV-negative: 5.6, p = 0.09). The two groups did not differ on any other sleep variables. Both groups had high rates of poor sleep quality as indicated by <85% efficiency (PWH: 77%; HIV-negative: 78%), <7 hours of sleep (PWH: 81%, HIV-negative: 78%), and a score >5 of the PSQI (PWH: 71%, HIV-negative: 59%).

Correlations Between Objective and Subjective Sleep Quality

None of the objective sleep measures (i.e., efficiency, total sleep time, or sleep fragmentation index) were significantly correlated with the total PSQI score (p’s > 0.30). However, subjective total sleep time reported on the PSQI was strongly correlated with objective total sleep time (r = 0.66, p < 0.01), but subjective total sleep time (M=6.8 hours) was approximately an hour greater than objective total sleep time (M=5.8 hours). Anxiety and depression were also positively correlated with the PSQI (ρ = 0.52, p <0.01; ρ = 0.33, p <0.01), whereas only sleep fragmentation index was significantly negatively correlated with anxiety (ρ = −0.26, p = 0.02). All objective sleep measures were correlated with one another (p’s < 0.01). See Table 4 for correlation coefficients for the entire sample and by HIV serostatus.

Table 4.

Correlations between objective and subjective sleep measures

| Efficiency | Objective TST | SFI | PSQI Total Score | Subjective TST | BDI-II | BAI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Participants (N=84) | |||||||

| Efficiency | 1 | ||||||

| Objective TST | 0.56** | 1 | |||||

| SFI | −0.84** | −0.46** | 1 | ||||

| PSQI Total | 0.04 | −0.10 | −0.10 | 1 | |||

| Subjective TST | 0.14 | 0.66** | −0.09 | −0.49** | 1 | ||

| BDI-II | 0.16 | 0.13 | −0.14 | 0.52** | 0.00 | 1 | |

| BAI | 0.17 | 0.03 | −0.26* | 0.33** | −0.04 | 0.52** | 1 |

| HIV+ (n=52) | |||||||

| Efficiency | 1 | ||||||

| TST | 0.55** | 1 | |||||

| SFI | −0.82** | −0.43** | 1 | ||||

| PSQI Total | 0.11 | −0.09 | −0.14 | 1 | |||

| Subjective TST | 0.15 | 0.67** | −0.11 | −0.47** | 1 | ||

| BDI-II | 0.16 | 0.08 | −0.17 | 0.52** | −0.07 | 1 | |

| BAI | 0.11 | −0.03 | −0.26 | 0.28* | 0.00 | 0.56** | 1 |

| HIV− (n=32) | |||||||

| Efficiency | 1 | ||||||

| Objective TST | 0.58** | 1 | |||||

| SFI | −0.87** | −0.50** | 1 | ||||

| PSQI Total | −0.22 | −0.18 | 0.08 | 1 | |||

| Subjective TST | 0.11 | 0.66** | −0.02 | −0.62** | 1 | ||

| BDI-II | −0.06 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.32 | 0.06 | 1 | |

| BAI | 0.15 | 0.20 | −0.20 | 0.24 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 1 |

Note. Pearson correlations were used for sleep variables, Spearman correlations for anxiety and depression and sleep variables. Objective TST = Actigraphy Total Sleep Time; Subjective TST = PSQI Total Sleep Time; SFI = sleep fragmentation index; PSQI = Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory-II; BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory

p<0.05;

p<0.01

Sleep and Cognition in the Overall Sample

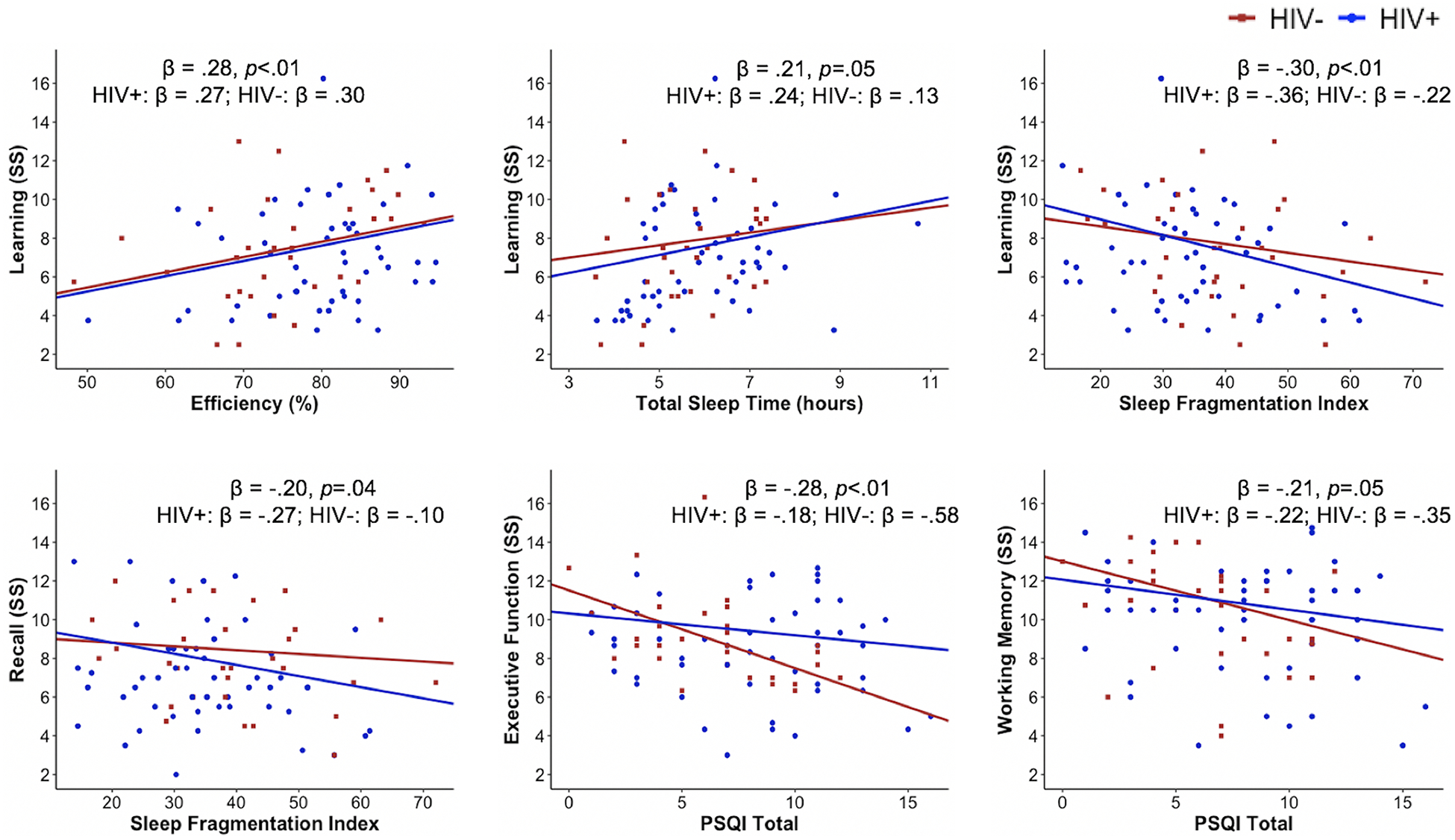

In the overall sample, greater efficiency (β = 0.28, p = 0.009) and greater total sleep time (β = 0.21, p = 0.051) were associated with better learning. Lower sleep fragmentation index scores also were associated with better learning (β = −0.30, p = 0.003) and recall (β = −0.20, p = 0.035). Additionally, lower subjective PSQI scores were associated with better executive function (β = −0.28, p = 0.006) and working memory (β = −0.21, p = 0.047). See Table 5 for model estimates and see Figure 1 for significant findings.

Table 5.

Linear regressions to examine the relationship between sleep and neurocognitive functioning in middle-aged and older adults with and without HIV (N=84)

| Domain (Scaled Scores) | Estimate | SE | 95% CI | Std. Estimate | T | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Efficiency | ||||||

| Global | 0.021 | 0.021 | [−0.021, 0.062] | 0.103 | 0.99 | 0.324 |

| Verbal | −0.002 | 0.034 | [−0.070, 0.066] | −0.008 | −0.06 | 0.949 |

| Executive Function | 0.015 | 0.026 | [−0.037, 0.066] | 0.060 | 0.56 | 0.574 |

| SIP | 0.013 | 0.027 | [−0.042, 0.068] | 0.053 | 0.48 | 0.635 |

| Learning | 0.079 | 0.030 | [0.020, 0.138] | 0.283 | 2.65 | 0.009* |

| Recall | 0.051 | 0.027 | [−0.003, 0.104] | 0.193 | 1.89 | 0.063 |

| Working Memory | 0.003 | 0.033 | [−0.062, 0.067] | 0.009 | 0.08 | 0.936 |

| Motor | 0.015 | 0.031 | [−0.048, 0.077] | 0.056 | 0.47 | 0.638 |

| Total Sleep Time | ||||||

| Global | 0.201 | 0.150 | [−0.098, 0.499] | 0.132 | 1.34 | 0.184 |

| Verbal | 0.010 | 0.246 | [−0.481, 0.501] | 0.005 | 0.04 | 0.969 |

| Executive Function | 0.208 | 0.187 | [−0.164, 0.580] | 0.112 | 1.12 | 0.268 |

| SIP | 0.176 | 0.198 | [−0.218, 0.570] | 0.093 | 0.89 | 0.376 |

| Learning | 0.436 | 0.220 | [−0.001, 0.873] | 0.207 | 1.99 | 0.051 |

| Recall | 0.312 | 0.196 | [−0.078, 0.702] | 0.157 | 1.60 | 0.115 |

| Working Memory | 0.244 | 0.233 | [−0.220, 0.709] | 0.111 | 1.05 | 0.298 |

| Motor | 0.207 | 0.227 | [−0.246, 0.659] | 0.103 | 0.91 | 0.365 |

| Sleep Fragmentation Index | ||||||

| Global | −0.017 | 0.015 | [−0.048, 0.013] | −0.110 | −1.14 | 0.260 |

| Verbal | 0.000 | 0.025 | [−0.050, 0.050] | 0.002 | 0.02 | 0.986 |

| Executive Function | −0.017 | 0.019 | [−0.055, 0.021] | −0.090 | −0.91 | 0.365 |

| SIP | −0.012 | 0.020 | [−0.052, 0.029] | −0.059 | −0.58 | 0.567 |

| Learning | −0.067 | 0.022 | [−0.110, −0.024] | −0.304 | −3.09 | 0.003* |

| Recall | −0.042 | 0.020 | [−0.081, −0.003] | −0.204 | −2.15 | 0.035 |

| Working Memory | −0.001 | 0.024 | [−0.048, 0.047] | −0.002 | −0.02 | 0.983 |

| Motor | −0.004 | 0.023 | [−0.050, 0.042] | −0.019 | −0.17 | 0.867 |

| PSQI Score | ||||||

| Global | −0.067 | 0.051 | [−0.169, 0.034] | −0.130 | −1.32 | 0.191 |

| Verbal | −0.094 | 0.085 | [−0.264, 0.075] | −0.129 | −1.11 | 0.271 |

| Executive Function | −0.175 | 0.062 | [−0.298, −0.052] | −0.278 | −2.84 | 0.006* |

| SIP | −0.055 | 0.067 | [−0.189, 0.079] | −0.085 | −0.82 | 0.415 |

| Learning | −0.033 | 0.077 | [−0.186, 0.120] | −0.045 | −0.43 | 0.669 |

| Recall | 0.028 | 0.067 | [−0.105, 0.161] | 0.041 | 0.41 | 0.680 |

| Working Memory | −0.158 | 0.078 | [−0.313, −0.002] | −0.211 | −2.02 | 0.047 |

| Motor | 0.042 | 0.078 | [−0.114, 0.198] | 0.061 | 0.53 | 0.596 |

Note. Objective sleep quality models include HIV status, age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, use of sleep medications and obstructive sleep apnea risk composite. Subjective sleep quality models include HIV status, age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, and obstructive sleep apnea risk composite.

CI = Confidence Interval; SIP = speed of information processing; PSQI=Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

denotes that finding is significant after correcting for multiple comparisons (Bonferroni correction; 0.05/4 = 0.0125)

Figure 1.

Significant relationships between sleep quality and cognition by HIV status

Note. Standardized beta coefficients and p-values in figures are presented for the overall sample and then by HIV serostatus. Regression lines are adjusted for covariates. HIV+ n = 52; HIV− n = 32

SS = Scaled score; PSQI = Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

Stratified Analyses

When stratifying the objective sleep analyses by HIV serostatus, with consequent reduction in statistical power, the relationship between sleep efficiency and learning was similar for the PWH and HIV-negative groups (PWH: β = 0.27, p = 0.062; HIV-negative: β = 0.30, p = 0.153). The relationship between total sleep time and learning was slightly greater in PWH (β = 0.24, p = 0.091) than in the HIV-negative group (β = 0.13, p = 0.507). The relationships between the sleep fragmentation index and learning and memory were slightly greater in PWH (learning: β = −0.36, p = 0.008; recall: β = −0.27, p = 0.019) than the HIV-negative group (learning: β = −0.22, p = 0.250; recall: β = −0.10, p = 0.609).

When stratifying the subjective sleep analyses, the PSQI total score was not significantly related to executive function (β = −0.18, p = 0.151) or working memory (β = −0.22, p = 0.126) in PWH. Better PSQI scores were significantly associated with better global cognitive functioning (β = −0.42, p = 0.014), executive function (β = −0.58, p = 0.001), and working memory (β = −0.35, p = 0.047) in the HIV-negative group. See Table 6 for stratified model estimates.

Table 6.

Linear regressions to examine the relationship between sleep and neurocognitive functioning by HIV serostatus

| HIV+ (n=52) | HIV− (n=32) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain (Scaled Scores) | Estimate | Std. Estimate | p-value | Estimate | Std. Estimate | p-value |

| Average Efficiency | ||||||

| Global | 0.009 | 0.042 | 0.752 | 0.039 | 0.202 | 0.315 |

| Executive Function | 0.006 | 0.021 | 0.869 | 0.049 | 0.220 | 0.319 |

| Learning | 0.079 | 0.266 | 0.062 | 0.079 | 0.295 | 0.153 |

| Recall | 0.061 | 0.220 | 0.071 | 0.034 | 0.131 | 0.535 |

| Working Memory | −0.018 | −0.060 | 0.680 | 0.020 | 0.069 | 0.732 |

| Average Total Sleep Time (hours) | ||||||

| Global | 0.174 | 0.124 | 0.336 | 0.483 | 0.277 | 0.142 |

| Executive Function | 0.147 | 0.083 | 0.501 | 0.733 | 0.357 | 0.081 |

| Learning | 0.465 | 0.237 | 0.091 | 0.323 | 0.132 | 0.507 |

| Recall | 0.418 | 0.229 | 0.054 | −0.027 | −0.011 | 0.955 |

| Working Memory | 0.153 | 0.076 | 0.592 | 0.523 | 0.200 | 0.292 |

| Average Sleep Fragmentation Index | ||||||

| Global | −0.014 | −0.086 | 0.498 | −0.015 | −0.101 | 0.581 |

| Executive Function | −0.021 | −0.101 | 0.399 | −0.019 | −0.107 | 0.593 |

| Learning | −0.082 | −0.356 | 0.008 | −0.045 | −0.215 | 0.250 |

| Recall | −0.058 | −0.272 | 0.019 | −0.020 | −0.097 | 0.609 |

| Working Memory | −0.002 | −0.010 | 0.942 | 0.016 | 0.072 | 0.694 |

| PSQI Score | ||||||

| Global | −0.031 | −0.062 | 0.635 | −0.245 | −0.415 | 0.014 |

| Executive Function | −0.112 | −0.180 | 0.151 | −0.402 | −0.578 | 0.001 |

| Learning | 0.027 | 0.038 | 0.790 | −0.248 | −0.299 | 0.092 |

| Recall | 0.073 | 0.112 | 0.362 | −0.176 | −0.232 | 0.208 |

| Working Memory | −0.155 | −0.215 | 0.126 | −0.303 | −0.347 | 0.047 |

Note. Objective sleep quality models include age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, use of sleep medications and obstructive sleep apnea risk composite. Subjective sleep quality models include age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, and obstructive sleep apnea risk composite.

PSQI=Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

Discussion

Sleep and cognition, individually, have been widely researched in PWH; however, the associations between measures of both objective and subjective sleep quality and cognitive functioning have still been relatively unexplored, particularly in older PWH. Overall, in this sample of middle-aged and older PWH with well-controlled HIV and demographically-similar HIV-negative comparison participants, we found both groups had high rates of poor objective and subjective sleep quality. However, subjective and objective sleep quality in PWH in this study was similar to other studies of middle-aged PWH (Gamaldo et al., 2013; Lee et al. 2012). Additionally, other studies of middle-aged HIV-negative adults report fairly similar findings (with the exception of efficiency, which was somewhat worse in this group; Gamaldo et al., 2013; Rena et al., 2018; Jurado-Fasoli et al., 2018). Interestingly, PWH had significantly better objective sleep efficiency; however, this was a difference of 5%, which may not be clinically meaningful, and the effect was somewhat attenuated (i.e., 3.1%) when accounting for OSA risk, use of sleep medications, and sex. Additionally, PWH were more likely to be taking sleep medication. This may suggest that PWH in this study are more engaged in medical care or that their doctors were more likely to ask about sleep problems and prescribe medications to treat insomnia. PWH reported slightly worse subjective sleep quality, which may also be contributing to use of sleep medications. Moreover, while high rates of poor subjective sleep quality have been reported in PWH, not all studies in the post-cART era find that PWH have greater rates of poor sleep quality compared to their HIV-negative peers (Crum-Cianflone et al., 2012).

The results from this study demonstrate both objective and subjective sleep quality were associated with cognitive function in the total sample; however, objective and subjective sleep quality were associated with different cognitive domains. Objectively-measured average sleep quality, assessed using wrist actigraphy, were associated with learning, and average sleep fragmentation was associated with recall. When stratifying analyses, average total sleep time and average sleep fragmentation were slightly more strongly associated with learning and recall in PWH. Future studies with more power to detect differences by HIV serostatus are warranted in order to determine if this is a clinically meaningful difference. The association between sleep and learning is consistent with the Mahmood et al. (2019) study, which found poor subjective sleep quality was associated with learning in a somewhat younger group of PWH. Additionally, studies in older adult samples have found that objectively-measured efficiency and fragmentation, but not the subjective PSQI score, are associated with worse learning and memory (Cabanel, Speier, Müller, & Kundermann, 2019; Cavuoto et al., 2016). The aging literature also suggests that long total sleep time may be worse for cognition than short total sleep time (Devore, Grodstein, & Schernhammer, 2016); however, our study had only one person with longer sleep time (i.e., >9 hours), so long versus short sleep time could not be evaluated. Nevertheless, the observed sleep-learning association is additionally consistent with a proposed mechanism of the sleep-cognition relationships in aging adults, as poor sleep is hypothesized to be associated with neurodegenerative conditions and impaired neurogenesis in hippocampal areas (Yaffe et al., 2014).

Subjective sleep quality, measured with the PSQI, was positively associated with executive function and working memory. When stratifying analyses, it appeared this association was driven by the HIV-negative group. In the HIV literature, Gamaldo et al. (2013) did not find any significant associations between the PSQI and results on objective neuropsychological testing. Conversely, Mahmood et al. (2019) found that subjective sleep was associated with learning and memory; however, they assessed sleep using a different self-report instrument (i.e., the SATED). In older adults, some research has found that worse PSQI total scores are associated with worse executive function and working memory; however, other studies have not observed this relationship or have found that PSQI scores are related to other cognitive domains (Brewster, Varrasse, & Rowe, 2015). Structural neuroimaging research has found that poor sleep quality is linked with brain regions associated with executive function (i.e., prefrontal cortex and orbitofrontal cortex; Joo et al., 2013). Other studies of older adults and PWH suggest that the PSQI may be influenced by depression and anxiety (Buysse et al., 2008; Fekete, Williams, & Skinta, 2018; Potvin, Lorrain, Belleville, Grenier, & Preville, 2014); therefore, greater anxiety and depression symptoms in PWH may be confounding the relationship between the PSQI and cognition in older PWH. Nonetheless, subjective sleep quality remains an important health behavior to assess as it may be associated with cognition, but more research is needed to understand how negative affect may modify this relationship among older PWH.

We found that, in both groups, the objective sleep quality measures were not correlated to the total PSQI subjective sleep quality score. This is not surprising given that the PSQI is a screening assessment that queries about a wide range of sleep behaviors (e.g., daytime dysfunction, use of sleep medications) not assessed by objective sleep quality methods. Additionally, these findings are in line with other studies in older adults and PWH that have found PSQI scores are not related to objective sleep measures (Buysse et al., 1991; Byun, Gay, & Lee, 2016). However, objective total sleep time measured via actigraphy and subjective total sleep time on the PSQI were strongly correlated, although self-reported total sleep time was approximately an hour greater than what was collected using wrist actigraphy. This is also unsurprising given that other studies have reported that poor sleepers are more likely to overestimate their total sleep time (Van Den Berg et al., 2008). These findings underscore the importance of assessing both objective and subjective sleep quality.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the results. First, while this study was conducted over a period of two weeks, this study is considered cross-sectional so we cannot assess causality. Longitudinal studies are needed to examine if sleep is associated with long-term cognitive changes, and studies that assess daily fluctuations using ecological momentary assessment are needed to examine how sleep is associated with daily fluctuations in cognition. Second, while we attempted to account for obstructive sleep apnea risk, we did not formally assess obstructive sleep apnea. Although obstructive sleep apnea is an important consideration in sleep research, it is difficult to account for because it is underdiagnosed (Terry Young, Peppard, & Gottlieb, 2002). Therefore, future studies may consider incorporating sleep apnea assessments via polysomnography or obstructive sleep apnea screening questionnaires. Similarly, while we attempted to account for use of sleep medications, many sleep medications are prescribed for other conditions. For example, Trazadone’s main indication is for depression but is commonly used for insomnia on an off-label basis. Future studies should further assess indications for medication use as well as consider off-label indications. Third, the objective sleep assessment took place after the neuropsychological testing and PSQI administration. While the objective sleep measures should be interpreted as average sleep quality, the difference in time frame could somewhat account for the relative lack of correlation between objective and subjective sleep quality measures. Fourth, while we accounted for demographic factors, due to limited sample size we were not able to examine if the relationship between sleep and cognition differs by demographic factors (e.g., sex, race/ethnicity). Future studies should explore how the association between cognition and sleep may differ by sociodemographic factors. Lastly, due to the limited research on cognition and sleep in older PWH, we decided to look at each cognitive domain which resulted in several analyses. When correcting for multiple comparisons, not all results remained significant. However, the overall pattern in which objective sleep measures were associated with learning and subjective sleep was associated with executive functioning remained. Nevertheless, future studies with larger samples that utilize conservative statistical approaches should be conducted. Despite these limitations, this study is one of the first to examine neurocognitive function and both subjective and objective sleep quality in older persons with and without HIV and provides important and clinically useful information.

Overall, these findings highlight that sleep quality is an important health behavior to assess in persons with and without HIV when evaluating cognition as it is related to different cognitive domains, but domains that are commonly affected in HIV and aging. Furthermore, both subjective and objective sleep quality should both be examined as each provide different clinically-useful information. Sleep quality is of particular interest to investigate as a potentially modifiable health behavior within the context of cognitive impairment and neurodegenerative diseases, given that cognitive impairment is difficult to treat, but there are behavioral interventions that have been shown to improve sleep quality (Buchanan et al., 2018; Okajima, Komada, & Inoue, 2011). Some research has shown that treatment of sleep apnea using a CPAP machine has improved cognitive functioning (Canessa et al., 2011; Ferini-Strambi et al., 2003). Moreover, treatment of insomnia (i.e., Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia) and sleep apnea have been shown to improve quality of life in the general population (Diamanti et al., 2013; Espie et al., 2019). These behavioral interventions may be particularly helpful given that many sleep medications (i.e., benzodiazepines and z-drugs) have been associated with negative cognitive (e.g., memory loss) and psychomotor events (e.g., falls) in older adults (Glass, Lanctot, Herrmann, Sproule, & Busto, 2005). Therefore, behavioral interventions targeting sleep quality are needed to examine if improving sleep quality can help promote successful cognitive aging outcomes in older PWH.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the leadership and staff of the Exercise and Physical Activity Resource Center (EPARC) at the University of California, San Diego for providing measurement and data processing support and the participants for their contributions.

Financial Support

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R.C.M., grant numbers NIMH K23MH105297, NIMH K23 MH107260 S1, NIA R01AG062387), (L.M.C., NIDA T32 DA031098), (M.K., NIAAA T32AA013525), (C.K., NIA K01AG061239) and (J.D.D., NIA R25AG043364).

The HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center (HNRC) is supported by Center award P30MH062512 from NIMH.

The San Diego HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center [HNRC] group is affiliated with the University of California, San Diego, the Naval Hospital, San Diego, and the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System, and includes: Director: Robert K. Heaton, Ph.D., Co-Director: Igor Grant, M.D.; Associate Directors: J. Hampton Atkinson, M.D., Ronald J. Ellis, M.D., Ph.D., and Scott Letendre, M.D.; Center Manager: Jennifer Iudicello, Ph.D.; Donald Franklin, Jr.; Melanie Sherman; NeuroAssessment Core: Ronald J. Ellis, M.D., Ph.D. (P.I.), Scott Letendre, M.D., Thomas D. Marcotte, Ph.D., Christine Fennema-Notestine, Ph.D., Debra Rosario, M.P.H., Matthew Dawson; NeuroBiology Core: Cristian Achim, M.D., Ph.D. (P.I.), Ana Sanchez, Ph.D., Adam Fields, Ph.D.; NeuroGerm Core: Sara Gianella Weibel, M.D. (P.I.), David M. Smith, M.D., Rob Knight, Ph.D., Scott Peterson, Ph.D.; Developmental Core: Scott Letendre, M.D. (P.I.), J. Allen McCutchan; Participant Accrual and Retention Unit: J. Hampton Atkinson, M.D. (P.I.) Susan Little, M.D., Jennifer Marquie-Beck, M.P.H.; Data Management and Information Systems Unit: Lucila Ohno-Machado, Ph.D. (P.I.), Clint Cushman; Statistics Unit: Ian Abramson, Ph.D. (P.I.), Florin Vaida, Ph.D. (Co-PI),, Anya Umlauf, M.S., Bin Tang, M.S.

Footnotes

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, nor the United States Government.

Declaration of Interest

Dr. R.C. Moore is a co-founder of KeyWise, Inc. and a Consultant for NeuroUX. These roles do not represent a conflict of interest with this study. No other authors report personal or financial conflicts of interest.

References

- Allavena C, Guimard T, Billaud E, De la Tullaye S, Reliquet V, Pineau S, −Group, C. O.-P. d. l. L. T. d. S. S. (2016). Prevalence and Risk Factors of Sleep Disturbance in a Large HIV-Infected Adult Population. AIDS Behav, 20, 339–344. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1160-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antinori A, Arendt G, Becker JT, Brew BJ, Byrd DA, Cherner M, −Wojna VE (2007). Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology, 69, 1789–1799. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000287431.88658.8b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Army individual test battery. (1944). Manual of directions and scoring. Washington, DC: War Department, Adjutant General’s Office. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, & Steer RA (1988). An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol, 56, 893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, & Brown GK (1996). Beck depression inventory-II. San Antonio, 78, 490–498. [Google Scholar]

- Benedict R (1997). Brief visuospatial memory test-revised: professional manual. Odessa, Florida: Psychological Assessment Resources. In: Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Benton L, Hamsher K, & Sivan A (1994). Controlled oral word association test. Multilingual aphasia examination, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt J, & Benedict R (2001). Hopkins Verbal Learning Test—Revised. Professional manual. Lutz, FL: Psychol Assessm Resources. In: Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Brewster GS, Varrasse M, & Rowe M (2015). Sleep and cognition in community-dwelling older adults: A review of literature. Paper presented at the Healthcare. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Buchanan DT, McCurry SM, Eilers K, Applin S, Williams ET, & Voss JG (2018). Brief Behavioral Treatment for Insomnia in Persons Living with HIV. Behav Sleep Med, 16, 244–258. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2016.1188392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucks RS, Olaithe M, & Eastwood P (2013). Neurocognitive function in obstructive sleep apnoea: a meta-review. Respirology, 18, 61–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2012.02255.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ, Hall ML, Strollo PJ, Kamarck TW, Owens J, Lee L, −Matthews KA (2008). Relationships Between the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), and Clinical/Polysomnographic Measures in a Community Sample. Journal of clinical sleep medicine, 4, 563–571. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, & Kupfer DJ (1989). The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res, 28, 193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Hoch CC, Yeager AL, & Kupfer DJ (1991). Quantification of Subjective Sleep Quality in Healthy Elderly Men and Women Using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (Psqi). Sleep, 14, 331–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byun E, Gay CL, & Lee KA (2016). Sleep, Fatigue, and Problems With Cognitive Function in Adults Living With HIV. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care, 27, 5–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2015.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabanel N, Speier C, Müller MJ, & Kundermann B (2019). Actigraphic, but not subjective, sleep measures are associated with cognitive impairment in memory clinic patients. Psychogeriatrics. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canessa N, Castronovo V, Cappa SF, Aloia MS, Marelli S, Falini A, −Ferini-Strambi L (2011). Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Brain Structural Changes and Neurocognitive Function before and after Treatment. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine, 183, 1419–1426. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201005-0693OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavuoto MG, Ong B, Pike KE, Nicholas CL, Bei B, & Kinsella GJ (2016). Objective but not subjective sleep predicts memory in community-dwelling older adults. Journal of sleep research, 25, 475–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherner M, Ellis RJ, Lazzaretto D, Young C, Mindt MR, Atkinson JH, −Group, H. I. V. N. R. C. (2004). Effects of HIV-1 infection and aging on neurobehavioral functioning: preliminary findings. AIDS, 18 Suppl 1, S27–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole RJ, Kripke DF, Gruen W, Mullaney DJ, & Gillin JC (1992). Automatic sleep/wake identification from wrist activity. Sleep, 15, 461–469. doi: 10.1093/sleep/15.5.461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley K (2011). Sleep and sleep disorders in older adults. Neuropsychol Rev, 21, 41–53. doi: 10.1007/s11065-010-9154-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crum-Cianflone NF, Roediger MP, Moore DJ, Hale B, Weintrob A, Ganesan A, −Letendre S (2012). Prevalence and Factors Associated With Sleep Disturbances Among Early-Treated HIV-Infected Persons. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 54, 1485–1494. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cysique LA, Franklin D, Abramson I, Ellis RJ, Letendre S, Collier A, −Grp, H. (2011). Normative data and validation of a regression based summary score for assessing meaningful neuropsychological change. Journal of clinical and experimental neuropsychology, 33, 505–522. doi:Pii 934517506 doi: 10.1080/13803395.2010.535504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devore EE, Grodstein F, & Schernhammer ES (2016). Sleep Duration in Relation to Cognitive Function among Older Adults: A Systematic Review of Observational Studies. Neuroepidemiology, 46, 57–78. doi: 10.1159/000442418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamanti C, Manali E, Ginieri-Coccossis M, Vougas K, Cholidou K, Markozannes E, −Alchanatis M (2013). Depression, physical activity, energy consumption, and quality of life in OSA patients before and after CPAP treatment. Sleep and breathing, 17, 1159–1168. doi: 10.1007/s11325-013-0815-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espie CA, Emsley R, Kyle SD, Gordon C, Drake CL, Siriwardena AN, −Luik AI (2019). Effect of Digital Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia on Health, Psychological Well-being, and Sleep-Related Quality of Life: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA psychiatry, 76, 21–30. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.2745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eugene AR, & Masiak J (2015). The Neuroprotective Aspects of Sleep. MEDtube science, 3, 35–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fekete EM, Williams SL, & Skinta MD (2018). Internalised HIV-stigma, loneliness, depressive symptoms and sleep quality in people living with HIV. Psychol Health, 33, 398–415. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2017.1357816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferini-Strambi L, Baietto C, Di Gioia MR, Castaldi P, Castronovo C, Zucconi M, & Cappa SF (2003). Cognitive dysfunction in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA): partial reversibility after continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). Brain Res Bull, 61, 87–92. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(03)00068-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Full KM, Kerr J, Grandner MA, Malhotra A, Moran K, Godoble S, −Soler X (2018). Validation of a physical activity accelerometer device worn on the hip and wrist against polysomnography. Sleep Health, 4, 209–216. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2017.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fultz NE, Bonmassar G, Setsompop K, Stickgold RA, Rosen BR, Polimeni JR, & Lewis LD (2019). Coupled electrophysiological, hemodynamic, and cerebrospinal fluid oscillations in human sleep. science, 366, 628–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallego L, Barreiro P, del Rio R, Gonzalez de Requena D, Rodriguez-Albarino A, Gonzalez-Lahoz J, & Soriano V (2004). Analyzing sleep abnormalities in HIV-infected patients treated with Efavirenz. Clin Infect Dis, 38, 430–432. doi: 10.1086/380791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamaldo CE, Gamaldo A, Creighton J, Salas RE, Selnes OA, David PM, −McArthur JC (2013). Sleep and cognition in an HIV+ cohort: a multi-method approach. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999), 63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass J, Lanctot KL, Herrmann N, Sproule BA, & Busto UE (2005). Sedative hypnotics in older people with insomnia: meta-analysis of risks and benefits. Bmj, 331, 1169. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38623.768588.47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden CJ, & Freshwater SM (1978). Stroop color and word test.

- Gronwall D (1977). Paced auditory serial-addition task: a measure of recovery from concussion. Perceptual and motor skills, 44, 367–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Clifford DB, Franklin DR Jr., Woods SP, Ake C, Vaida F, −Group, C. (2010). HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER Study. Neurology, 75, 2087–2096. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318200d727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeste DV, Palmer BW, Appelbaum PS, Golshan S, Glorioso D, Dunn LB, −Kraemer HC (2007). A new brief instrument for assessing decisional capacity for clinical research. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 64, 966–974. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.8.966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joo EY, Noh HJ, Kim JS, Koo DL, Kim D, Hwang KJ, −Hong SB (2013). Brain Gray Matter Deficits in Patients with Chronic Primary Insomnia. Sleep, 36, 999–1007. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurado-Fasoli L, Amaro-Gahete FJ, De-la-O A, Dote-Montero M, Gutiérrez Á, & Castillo MJ (2018). Association between sleep quality and body composition in sedentary middle-aged adults. Medicina, 54, 91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kløve H (1963). Grooved pegboard. Lafayette, IN: Lafayette Instruments. [Google Scholar]

- Knutson KL, Van Cauter E, Zee P, Liu K, & Lauderdale DS (2011). Cross-sectional associations between measures of sleep and markers of glucose metabolism among subjects with and without diabetes: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Sleep Study. Diabetes Care, 34, 1171–1176. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kongs S, Thompson L, Iverson G, & Heaton R (2000). Wisconsin Card Sorting Test-64 Card Version Professional Manual. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. In: Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Landry GJ, Best JR, & Liu-Ambrose T (2015). Measuring sleep quality in older adults: a comparison using subjective and objective methods. Front Aging Neurosci, 7, 166. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2015.00166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KA, Gay C, Portillo CJ, Coggins T, Davis H, Pullinger CR, & Aouizerat BE (2012). Types of sleep problems in adults living with HIV/AIDS. J Clin Sleep Med, 8, 67–75. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.1666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee PH, & Suen LK (2017). The convergent validity of Actiwatch 2 and ActiGraph Link accelerometers in measuring total sleeping period, wake after sleep onset, and sleep efficiency in free-living condition. Sleep and breathing, 21, 209–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewen A, Siemens A, & Hanly P (2009). Sleep disruption in patients with sleep apnea and end-stage renal disease. J Clin Sleep Med, 5, 324–329. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood Z, Hammond A, Nunez RA, Irwin MR, & Thames AD (2018). Effects of Sleep Health on Cognitive Function in HIV+ and HIV− Adults. J Int Neuropsychol Soc, 24, 1038–1046. doi: 10.1017/S1355617718000607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makinson A, Dubois J, Eymard-Duvernay S, Leclercq P, Zaegel-Faucher O, Bernard L, −Berr C (2019). Increased Prevalence of Neurocognitive Impairment in Aging People Living With Human Immunodeficiency Virus: The ANRS EP58 HAND 55–70 Study. Clin Infect Dis. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malaspina L, Woods SP, Moore DJ, Depp C, Letendre SL, Jeste D, −Group, H. I. V. N. R. P. (2011). Successful cognitive aging in persons living with HIV infection. J Neurovirol, 17, 110–119. doi: 10.1007/s13365-010-0008-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore DJ, Fazeli PL, Moore RC, Woods SP, Letendre SL, Jeste DV, −Program, H. I. V. N. R. (2017). Positive Psychological Factors are Linked to Successful Cognitive Aging Among Older Persons Living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Behav. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-2001-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore RC, Fazeli PL, Jeste DV, Moore DJ, Grant I, Woods SP, & Group HIVNRP (2014). Successful cognitive aging and health-related quality of life in younger and older adults infected with HIV. AIDS Behav, 18, 1186–1197. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0743-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin CM, LeBlanc M, Daley M, Gregoire J, & Merette C (2006). Epidemiology of insomnia: prevalence, self-help treatments, consultations, and determinants of help-seeking behaviors. Sleep medicine, 7, 123–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh J, Eser RA, Ehrenberg AJ, Morales D, Petersen C, Kudlacek J, −Cosme C (2019). Profound degeneration of wake-promoting neurons in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 15, 1253–1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohayon MM (2002). Epidemiology of insomnia: what we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep medicine reviews, 6, 97–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okajima I, Komada Y, & Inoue Y (2011). A meta-analysis on the treatment effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for primary insomnia. Sleep and Biological Rhythms, 9, 24–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-8425.2010.00481.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peter-Derex L, Yammine P, Bastuji H, & Croisile B (2015). Sleep and Alzheimer’s disease. Sleep medicine reviews, 19, 29–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potvin O, Lorrain D, Belleville G, Grenier S, & Preville M (2014). Subjective sleep characteristics associated with anxiety and depression in older adults: a population-based study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry, 29, 1262–1270. doi: 10.1002/gps.4106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychological Corporation (1997). WAIS-III and WMS-III Technical Manual: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Ram S, Seirawan H, Kumar SK, & Clark GT (2010). Prevalence and impact of sleep disorders and sleep habits in the United States. Sleep and Breathing, 14, 63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rana BK, Panizzon MS, Franz CE, Spoon KM, Jacobson KC, Xian H, … & Kremen WS (2018). Association of sleep quality on memory-related executive functions in middle age. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 24(1), 67–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeh A, Sharkey KM, & Carskadon MA (1994). Activity-based sleep-wake identification: an empirical test of methodological issues. Sleep, 17, 201–207. doi: 10.1093/sleep/17.3.201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samji H, Cescon A, Hogg RS, Modur SP, Althoff KN, Buchacz K, −Design of Ie, D. E. A. (2013). Closing the gap: increases in life expectancy among treated HIV-positive individuals in the United States and Canada. PLoS One, 8, e81355. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute (2018). JMP Pro Version 14.0.0. Cary, NC: SAS Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Shi L, Chen SJ, Ma MY, Bao YP, Han Y, Wang YM, −Lu L (2018). Sleep disturbances increase the risk of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep medicine reviews, 40, 4–16. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2017.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Berg JF, Van Rooij FJ, Vos H, Tulen JH, Hofman A, Miedema HM, −Tiemeier H (2008). Disagreement between subjective and actigraphic measures of sleep duration in a population-based study of elderly persons. Journal of sleep research, 17, 295–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vosvick M, Gore-Felton C, Ashton E, Koopman C, Fluery T, Israelski D, & Spiegel D (2004). Sleep disturbances among HIV-positive adults: the role of pain, stress, and social support. J Psychosom Res, 57, 459–463. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing EJ (2016). HIV and aging. International journal of infectious diseases, 53, 61–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirth MD, Jaggers JR, Dudgeon WD, Hebert JR, Youngstedt SD, Blair SN, & Hand GA (2015). Association of Markers of Inflammation with Sleep and Physical Activity Among People Living with HIV or AIDS. AIDS Behav, 19, 1098–1107. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0949-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (1997). Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI, version 2.1). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Wu H, Lu C, Guo L, & Li P (2015). Self-reported sleep disturbances in HIV-infected people: a meta-analysis of prevalence and moderators. Sleep Med, 16, 901–907. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.03.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe K, Falvey CM, & Hoang T (2014). Connections between sleep and cognition in older adults. Lancet Neurology, 13, 1017–1028. doi:Doi 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70172-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young T, Peppard PE, & Gottlieb DJ (2002). Epidemiology of obstructive sleep apnea: a population health perspective. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine, 165, 1217–1239. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2109080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young T, Skatrud J, & Peppard PE (2004). Risk factors for obstructive sleep apnea in adults. JAMA, 291, 2013–2016. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.16.2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]