Abstract

RNA encoded by RNA viruses is highly regulated so that it can function in multiple roles during the viral life cycle. These roles include serving as the mRNA template for translation or the genetic material for replication as well as being packaged into progeny virions. RNA modifications provide an emerging regulatory dimension to the RNA of viruses. Modification of the viral RNA can increase the functional genomic capacity of the RNA viruses without the need to encode and translate additional genes. Further, RNA modifications can facilitate interactions with host or viral RNA-binding proteins that promote replication or can prevent interactions with antiviral RNA-binding proteins. The mechanisms by which RNA viruses facilitate modification of their RNA are diverse. In this review, we discuss some of these mechanisms, including exploring the unknown mechanism by which the RNA of viruses that replicate in the cytoplasm could acquire the RNA modification N6-methyladenosine.

Keywords: RNA modifications, N6-methyladenosine, RNA viruses, N7-methylguanosine, 2’-O methylation

Introduction

RNA viruses are incredibly simple and efficient parasites that depend on host processes to facilitate their replication. This can be seen in the RNA virus called hepatitis C virus (HCV). This virus only encodes 10 viral proteins in a RNA genome less than 10 000 bases in length, and yet it can completely reprogram a cell that expresses over 20 000 genes to carry out its replicative life cycle [1]. The genomes of RNA viruses are generally short because these viruses, which maintain their genetic material in an RNA state, rely on error prone viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (RdRp) for their replication [2]. There are examples of RNA viruses with longer genomes, but these viruses, including coronaviruses, actually encode an RNA proofreading enzyme [3]. Therefore, in general RNA viruses must utilize a diverse set of mechanisms to elicit further functionality from their genomes without increasing their genomic length, as the replication error drastically increases with genome length. Indeed, many such mechanisms have been described in RNA viruses, such as RNA structures, polycistronic expression cassettes, overlapping genes and, the focus of this review, RNA modifications [4].

The first modified nucleotide discovered nearly 60 years ago in RNA, once referred to as the ‘fifth nucleotide’, is pseudouridine [5, 6]. Since that discovery, hundreds of other modified RNA nucleotides have been identified in RNA, and many have been found to play important biological roles [7]. In mRNAs, these modified nucleotides have been shown to regulate many fundamental aspects of RNA biology such as translation initiation, trafficking, degradation and interaction with RNA-binding proteins [8]. Given the ability of RNA modifications to regulate nearly all aspects of RNA metabolism, it is unsurprising that they are found within the RNA of viruses. Indeed, work over the past few decades has defined important roles for a number of RNA modifications in viral life cycles. These modifications include the Cap modifications N7-methylguanosine (m7G) [9] and 2’-O methylation [10], the mRNA modification N6-methyladenosine (m6A) [11] as well as many others [12]. In many cases, these RNA modifications have been found to increase the functionality of the modified viral RNA by enabling or preventing RNA–protein interactions that promote or inhibit viral replication, respectively.

In nearly all aspects of cellular biology, viruses have evolved strategies to perturb cellular pathways and metabolism to benefit their own replication, including taking advantage of RNA modifications. While the mechanisms utilized by viruses to obtain some RNA modifications, especially m7G and 2’-O methylation, have been well described, the mechanisms used by other RNA viruses to obtain specific RNA modifications are often unclear, even when the function of the RNA modification to the viral life cycle is clear. In this review, we will explore some of the strategies used by RNA viruses to obtain RNA modifications and discuss how our understanding of these processes may help us to discover mechanisms by which the RNA of viruses that replicate in the cytoplasm become modified by m6A.

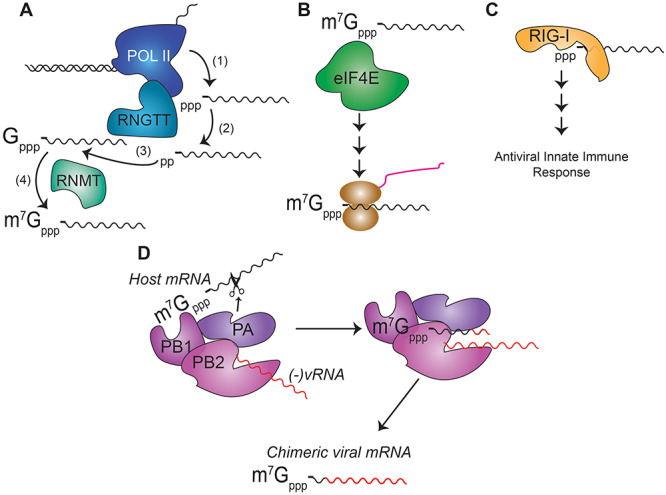

Influenza A virus and thief

In this section, we will describe how the viral mRNA of influenza A virus gains the m7G Cap modification, first describing how eukaryotic transcripts gain this modification. Nearly all eukaryotic mRNA transcripts are modified at the 5′ end with m7G in a process known as capping [13]. In cellular mRNAs this modification of transcripts with the Cap occurs during transcription when the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II (Pol II) associates with the enzymes that generate the 5′ terminal m7G modification for co-transcriptional modification of nascent pre-mRNAs in the nucleus [14, 15]. The enzymes that add the m7G modification are RNGTT and RNMT, and they catalyze the addition of this modification in four steps [16]. First transcription of a given RNA transcript is performed by Pol II. Second, RNGTT uses its RNA triphosphatase (RNA TPase) domain to remove the outer γ-phosphate from the first transcribed nucleotide. Third, RNGTT uses its guanylyl transferase (GTase) domain to add a guanine joined by a triphosphate bridge to the first nucleotide in a unique 5′ to 5′ bond as compared with normal 3′ to 5′ nucleotide linkages. Finally, RNMT, the guanine-N7 methyltransferase (GN7-MTase), methylates the added guanine at the N7 position (Figure 1A) [17]. Among the most important biological functions of m7G modification is its role in translational initiation, and nearly all eukaryotic mRNA transcripts require 5′ terminal m7G modification for efficient translation [18]. This is because the 5′ terminal m7G modification recruits eukaryotic initiation factors (eIFs) that then recruit the ribosome (Figure 1B) [19]. As such, RNA transcripts that lack 5′ terminal m7G modification are not efficiently translated. The m7G modification is also important for ‘self versus non-self’ detection by the immune system, as RNA transcripts lacking m7G and instead maintaining a 5′ triphosphate moiety are recognized and bound by cellular pattern recognition receptors, such as RIG-I, resulting in potent innate immune activation (Figure 1C) [20]. Thus, viral mRNAs must engage in m7G modification of their 5′ termini both to ensure successful translation and to evade activation of the innate immune response.

Figure 1.

mRNA capping by m7G. (A) The steps in mammalian m7G capping of mRNA: (1) transcription of a mRNA by Pol II, (2) removal of the γ-phosphate of the 5′ terminal triphosphate by the RNA TPase domain of RNGTT, (3) addition of a guanosine to the 5′ end of the transcript by the guanylyltransferase domain of RNGTT, (4) methylation at the N7 position of this newly added guanosine by RNMT resulting in the generation of the ‘Cap 0’ structure. (B) mRNA transcripts with an intact m7G at the 5′ terminus are bound by the translation initiation factor eIF4E, which recruits other translation factors for mRNA translation. (C) mRNA transcripts with a 5′ triphosphate that lack a 5′ m7G are bound by RIG-I, which activates a signaling cascade to induce the antiviral innate immune response. (D) Mechanism of influenza A virus ‘Cap snatching’ in which PB2 binds to host transcripts that are modified with m7G. These transcripts are then cleaved by the PA protein and this short cellular-derived RNA oligonucleotide with the m7G modification serves as a transcriptional primer for the viral RdRp PB1, which generates a chimeric host–viral RNA that possesses the host-derived 5′ m7G Cap.

While several virus families, including members of the Coronaviridae, encode their own capping enzymes [21], influenza A virus obtains the m7G Cap modification on its mRNA through a process known as ‘Cap snatching’. Influenza A virus, a member of the Orthomyxoviridae family of RNA viruses, has a negative sense, single-stranded RNA genome consisting of eight segments [22]. Early research on influenza A virus revealed that these RNA segments contained multiple RNA modifications, including terminal m7G on the viral mRNAs [23]. In contrast to most RNA viruses, influenza A virus replication occurs within the nucleus of infected cells, and thus, in theory it could utilize the host m7G modification machinery [24]. While the human enzymes responsible for m7G modification were unknown at the time, early work had identified that other viruses, such as vaccinia and reovirus, encoded their own m7G methylation capability [25, 26]. Thus, it was plausible that influenza A virus might encode its own m7G modification machinery, perhaps within its RdRp. As a negative-sense RNA virus, the influenza A virus virion contains the negative-sense viral RNAs and the viral polymerase complex, which includes the RdRp [27]. In the infected cell, this viral polymerase first transcribes the negative-sense viral RNAs into positive-sense mRNAs, which encode the remaining viral proteins required for replication. The initial transcription event for influenza is mediated by the viral polymerase complex, composed of the three proteins PB1, PB2 and PA. However, studies revealed that this viral polymerase complex was incapable of m7G modification of RNA, unlike the polymerases from vaccinia virus and reovirus [28, 29]. Fascinatingly, the mechanism for how influenza A virus mRNAs obtain m7G modification does not directly involve viral or cellular proteins with the canonical RNA TPase, GTase and GN7-MTase activities that act upon viral RNA. Instead, influenza A virus engages in a strategy known as ‘Cap snatching’ to generate viral transcripts that contain 5′ m7G modification.

Cap snatching by influenza A virus is reliant on the activity of all three proteins in the viral polymerase complex; however, none of these proteins are methyltransferases. The PB1 protein possesses RdRp activity [30], whereas PB2 and PA possess m7G Cap-binding activity and endonuclease activity, respectively [31, 32]. Interestingly, rather than making its own m7G Cap, influenza A virus acquires preexisting m7G Caps from host mRNAs [9, 33]. This unique mechanism of m7G capping is executed as follows: first, PB2 binds the m7G Cap of a host mRNA transcript. Then, the PA endonuclease protein cleaves this Cap and a short span of the 5′ end of the host transcript from the remainder of the RNA molecule. Finally, this short m7G capped RNA oligo is used as a primer for transcription by PB1, which generates a chimeric host–viral mRNA now containing a m7G Cap (Figure 1D) [21]. This elaborate mechanism of obtaining the m7G Cap means that the virus does not need to encode its own capping enzymes. In addition, it prevents the formation of a 5′ triphosphate moiety in the viral mRNA that could be sensed by cellular pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that trigger innate immune activation. This activity is essential for influenza virus replication, as viral resistance develops to the antiviral drug baloxavir marboxil, which inhibits viral capping [34]. On top of enabling viral translation, the Cap-snatching activity encoded by the virus also provides a secondary benefit to the virus in that the ‘donor’ RNA transcript, from which the m7G Cap and proximal nucleotides are cleaved, is no longer capable of being translated. Thus, in theory if specific antiviral transcripts served as ‘donor’ transcripts this would provide an outsized benefit to influenza A virus replication. However, current knowledge of the specificity of influenza A virus in selecting ‘donor’ transcripts suggests that influenza A virus mostly steals the Caps from highly abundant transcripts [35], noncoding RNAs [36] or exosome targeted transcripts [37]. As influenza A virus infects a wide variety of species, this approach of directly targeting the RNA modification rather than attempting to co-opt the cellular machinery is likely less susceptible to host genetic variation. Thus, influenza A virus mRNAs acquire m7G Caps by snatching them from cellular mRNAs.

Flaviviruses do it on their own

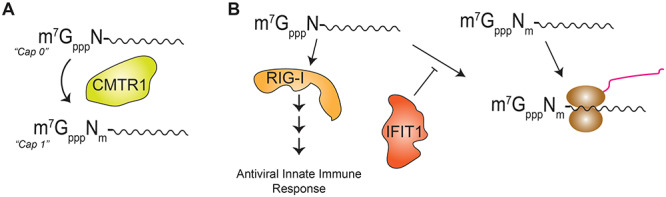

Flaviviruses, such as dengue (DENV), Zika (ZIKV) and West Nile virus, also have a canonical Cap structure at the 5′ terminus of their viral RNA. The viral RNA of flaviviruses is a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA genome of approximately 10 kb in length that encodes 10 distinct viral proteins [38]. The RNA Cap present on flaviviral RNA is similar to that of mRNA, which contains both the m7G modification and 2’-O-methylated nucleotides [39, 40]. This 2’-O methylation occurs on the first transcribed nucleotide adjacent to the Cap, which is termed ‘Cap 1’, whereas ‘Cap 0’ mRNAs have an m7G Cap, but lack 2’O methylation on the first nucleotide [41]. In contrast to the tripartite complex of cellular enzymes required for m7G modification, mRNA 2’-O methylation is performed by a single cellular protein called CMTR1 (Figure 2A). Interestingly, CMTR1 is upregulated in response to interferon [42, 43], and work by our lab has shown that CMTR1 is important for the antiviral innate immune response [44]. Cap 2’-O methylation of mRNAs promotes their translation [45] and shields them from the cellular pattern recognition receptor RIG-I and the antiviral protein IFIT1 [17, 46]. These proteins bind to RNAs lacking Cap 2’-O methylation and either activate innate immune signaling or impair translation of the transcript, respectively (Figure 2B) [10, 17]. Therefore, viral mRNAs Caps must either undergo both m7G and 2’-O methylation for successful translation and to evade immune activation in host cells or encode an ability to circumvent aspects of translational control, such as by using an internal ribosome entry site as seen in HCV or by encoding RNA elements that prevent IFIT1 binding as seen in alphaviruses [47, 48]. Indeed, the ‘Cap’ found on flavivirus RNA is a ‘Cap 1’ structure, thus enabling flaviviral translation through the canonical mRNA translation mechanisms without stimulating the host immune response [49, 50].

Figure 2.

Cellular 2’-O methylation machinery. (A) 2’-O methylation is performed by the cellular enzyme CMTR1, which methylates the first transcribed nucleotide of mRNA transcripts. (B) mRNA transcripts that lack 2’-O methylation are potent activators of the antiviral innate immune proteins RIG-I and IFIT1. Activated RIG-I signals to activate the antiviral innate immune response, whereas IFIT1 prevents non-2’-O methylated transcripts from being translated.

As flaviviruses replicate exclusively in the cytoplasm, their viral RNA cannot be modified by the cellular, nuclear localized enzymes that catalyze the formation of the mRNA Cap. The discovery of how m7G and 2’-O methylation were added to flavivirus RNA was the culmination of decades of work. Initially, computer modeling identified a putative domain within the flavivirus RdRp protein NS5 with homology to cellular 2’-O methyltransferases and this activity was confirmed by functional characterization [51, 52]. However, the NS5 protein contained no known homology to described GN7-MTase domains. Ultimately, in vitro experimentation with expressed viral proteins validated that the viral NS5 protein did encode both GN7-MTase and GTase activity [52–55], with the flaviviral NS3 protein providing the RNA TPase activity [56]. Together, these virally encoded capping activities of NS3 and NS5 allow flaviviruses to modify their RNA with the canonical ‘Cap 1’ structure. This allows successful translation of viral mRNA without involvement of the nuclear capping machinery. Importantly, by engaging in 2’-O methylation to generate ‘Cap 1’ rather than ‘Cap 0’ structures, flaviviruses are also able to evade immune restriction in infected cells [57]. Indeed, this viral intrinsic ability to generate Cap 1 structures with both m7G and 2’-O methylation has been found to be a major contributor to viral fitness [10]. Remarkably, the 2’-O methylation activity of the flaviviral NS5 protein has been found to also be active on internal adenosines within the viral RNA and impairing this internal methylation activity has a negative impact on viral fitness [58]. This internal 2’-O methylation activity has also been found in other RNA viruses such as members of the Filoviridae family that also encode the ability to generate Cap 1 structures on viral RNA transcripts [59]. Further, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) can recruit cellular enzymes to engage in internal 2’-O methylation of its viral RNA for immune evasion [60]. Recent work exploring internal 2’-O methylation in cellular mRNA has also shown that its presence can regulate mRNA expression and translation [61]. This suggests that flaviviral-encoded 2’-O methylation activity may serve additional functions for viral replication beyond simply the generation of ‘Cap 1’ structures.

Searching for a way to m6A

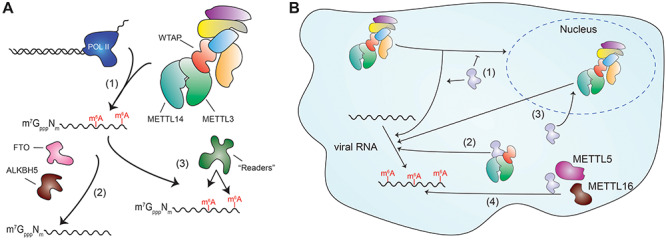

While the modifications discussed above are ‘terminal’ RNA modifications, meaning they occur at the end of mRNA transcripts, it is also appreciated that there are a significant number of RNA modifications that occur within an mRNA transcript, known as ‘internal’ modifications [7]. The most abundant internal mRNA modification is m6A. First described in the late 1960s, m6A is present in both viral and eukaryotic mRNA [23, 62–65]. m6A modification of mRNA is catalyzed by the enzyme METTL3 [66]. Importantly, METTL3 function is dependent on its association with a number of other proteins, such as METTL14 and WTAP, which together make up the m6A methyltransferase complex (‘writer complex’) [67–70]. This writer complex is highly abundant in the nucleus and engages in co-transcriptional m6A modification of nascent transcripts in association with Pol II [71, 72] (Figure 3A). m6A modification is found in DRAmCH RNA motifs (D = A/G/T, R = A/G, H = A/C/T); however, not all DRACH motifs are modified by m6A [73, 74]. This suggests that there are additional aspects controlling the specificity of m6A modification beyond this motif, likely conferred by the accessory proteins in the writer complex [75]. m6A modification is removed by the cellular enzymes FTO and ALBKH5 (‘erasers’) [76, 77]. Importantly, there many cellular proteins capable of specifically recognizing and binding m6A, and these proteins are referred to as ‘readers’ [78]. These proteins are important for many of the biological roles of m6A and are involved in regulating RNA trafficking and degradation, translational efficiency and splicing [79–85]. Yet even without interaction of a reader protein, m6A modification can regulate an RNA molecule by perturbing its structure or preventing proteins from binding to the modified transcript [80, 86]. With so many fundamental aspects of RNA biology impacted by m6A modification, it is unsurprising that it plays important roles in the life cycles of many RNA viruses.

Figure 3.

N6-methyladeonsine machinery and modification. (A) m6A modification of cellular mRNAs occurs during transcription when the methyltransferase complex associates with Pol II (1), modified transcripts are capable of being demethylated by enzymes including FTO and ALKBH5 (2) and modified transcripts can be bound by ‘reader’ proteins that influence many aspects of RNA biology, such as degradation and trafficking (3). (B) Possible mechanisms by which cytoplasmic RNA viruses acquire m6A methylation of their RNA mediated by the METTL3–METTL14–WTAP methyltransferase complex including: (1) redirection of the newly translated methyltransferase complex in the cytoplasm to be directed to viral RNA by a viral factor, (2) recruitment of only the catalytically active components of the methyltransferase complex to viral RNA by a viral factor, (3) viral-directed export of the entire methyltransferase complex from within the nucleus into the cytoplasm by a viral factor, (4) recruitment of other cellular m6A methyltransferase enzymes such as METTL5 or METTL16 to viral RNA.

Although m6A was found within viral RNA as early as the 1970s, its impacts on viruses have only recently begun to be unraveled [12, 23, 65]. The emergence of high-throughput techniques capable of mapping the location of m6A-modified residues on RNA molecules through the use of anti-m6A RNA immunoprecipitation have facilitated these studies [73, 74]. Using these methods, we and others were able to reveal that the m6A modification could be found on the RNA of multiple viruses and that m6A modification on viral RNA regulates viral replication in diverse ways [11, 12]. In HCV, m6A modification regulates the packaging of viral RNA into nascent viral particles [11], whereas in human metapneumovirus (HMPV), m6A modification of viral RNA prevents detection by the cellular pattern recognition receptor RIG-I [87], and in porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV), m6A modification negatively regulated viral RNA stability [88]. A number of RNA viruses that are m6A modified and regulated have cytoplasmic life cycles; these viruses include members of the Flaviviridae family including HCV, ZIKV, DENV [11], the Coronaviridae family, such as PEDV [89] and the Picornaviridae family, like Enterovirus 71 (EV71) [90]. For these viruses, viral replication and transcription all take place in the cytoplasm, catalyzed by a virally encoded RdRp. However, this stands in contrast to the canonical model of mRNA m6A methylation that occurs co-transcriptionally within the nucleus [72]. Thus, the mechanism of m6A modification of these cytoplasmic RNA viruses must differ from that of cellular mRNAs due to the cytoplasmic localization of their RNA and the mechanisms by which these viral RNAs are transcribed. Remarkably, the mystery of how these viruses obtain m6A modification on their RNA has not been fully solved.

Recent work may provide clues as to the cellular and viral proteins that are involved in m6A methylation of viral RNA in the cytoplasm. In HCV and HMPV, mutation of DRACH motifs in viral RNA resulted in decreased binding of m6A reader proteins to the viral RNA, revealing that these DRACH motifs are m6A modified [11, 87]. As DRACH motifs are targeted by the METTL3–METTL14–WTAP complex, it is likely that m6A methylation of these viral RNAs is performed by the canonical mRNA m6A methyltransferase complex. In support of this, during EV71 infection, depletion of METTL3 reduced the level of m6A methylation of viral RNA. Additionally, EV71 infection resulted in relocalization of WTAP, METTL3 and METTL14 to the cytoplasm, and the viral RdRp interacted with METTL14 and WTAP [90]. Likewise, during HMPV infection, METTL14 co-localizes in the cytoplasm with the viral N protein [87]. This change in localization of m6A writer complex proteins during infection demonstrates that certain viruses can influence the localization of these components. Together, these data imply that these viruses might engage in ‘hijacking’ the m6A writer complex to redirect it to the cytoplasmic sites of viral RNA replication to facilitate m6A modification of viral RNA (Figure 3B). With this approach, these cytoplasmic viruses would both be able to exploit the regulatory effects of m6A on their RNA transcripts and also potentially dysregulate the m6A-dependent regulation of host cell processes. Indeed, our lab and others have discovered that infection by many of these m6A regulated viruses leads to changes in the m6A modification landscape of host mRNAs [88, 91, 92].

Despite the emergence of studies that indicate a role for the METTL3 writer complex in modification of viral RNA with m6A, this may not be the universal mechanism of viral RNA m6A methylation for cytoplasmic RNA viruses. For example, surprisingly, perturbation of METTL3 and METTL14 does not impact m6A modification of PEDV RNA [88]. Indeed, there are other cellular proteins capable of m6A modification of structured RNA such as METTL16 and METTL5, and these might prove to be co-opted by certain viruses for m6A methylation of their RNA (Figure 3B) [93, 94]. Further, taking a lesson from other RNA viruses and their mechanisms of RNA modifications, it may be that some rare viruses encode the ability to catalyze m6A modification of their RNA, as with m7G modification and 2’-O methylation in flaviviruses. Alternatively, m6A modification of viral RNA could occur through a yet to be determined mechanism where none of the normal m6A machinery is involved, analogous to the lack of capping enzyme involvement in influenza A virus Cap snatching. Regardless, the incorporation of m6A in viral RNA and the regulatory effects seen in modified viruses are yet another example of how RNA viruses utilize RNA modifications to efficiently increase their replication toolset.

Conclusion

RNA viruses, by their nature, are paragons of efficiency. Despite most of these viruses having genomes the length of a single human gene, they manage to encode significant functionality for reprogramming of host cells for their replication. Among the viral strategies that allow for this are the clever utilization of RNA regulatory mechanisms, including RNA modifications, to facilitate their replication. RNA viruses have developed approaches to repurpose or circumvent these cellular processes for modification of their own RNA, such as influenza A virus ‘Cap snatching’ and the multiple enzymatic activities of flaviviral RdRp to catalyze flaviviral RNA capping. While the mechanisms for how viral RNA in the cytoplasm becomes m6A methylated are still unknown, recent work has provided clues that may lead to defining how this noncanonical m6A modification of cytoplasmic viral RNA occurs, which will undoubtedly reveal novel viral-directed mechanisms to circumvent normal host RNA metabolism.

Key Points

RNA viruses make extensive use of RNA modifications to facilitate their replication.

The host processes that generate these RNA modifications are often inaccessible to viruses.

RNA viruses have evolved a variety of mechanisms to facilitate their own RNA modification.

Acknowledgements

We thank Horner lab members, especially Michael McFadden, for discussion of this manuscript.

Matthew T. Sacco is a PhD candidate in the laboratory of Dr Stacy Horner whose work concerns the mechanisms utilized by Flaviviridae to engage in m6A modification of their viral RNA.

Stacy M. Horner: Dr Horner is an assistant professor in the Department of Molecular Genetics and Microbiology at Duke University whose work explores the interface of RNA modifications and viral infection.

Funding

Burroughs Wellcome Fund and National Institutes of Health (R01AI125416); National Institutes of Health (T32-CA009111) to M.T.S.

References

- 1. Moradpour D, Penin F, Rice CM. Replication of hepatitis C virus. Nat Rev Microbiol 2007;5(6):453–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Holmes EC. Error thresholds and the constraints to RNA virus evolution. Trends Microbiol 2003;11(12):543–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Denison MR, Graham RL, Donaldson EF, et al. Coronaviruses: an RNA proofreading machine regulates replication fidelity and diversity. RNA Biol 2011;8(2):270–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cross ST, Michalski D, Miller MR, et al. RNA regulatory processes in RNA virus biology. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 2019;10(5):e1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cohn WE, Volkin E. Nucleoside-5'-phosphates from ribonucleic acid. Nature 1951;167(4247):483–484. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Davis FF, Allen FW. Ribonucleic acids from yeast which contain a fifth nucleotide. J Biol Chem 1957;227(2):907–915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Boccaletto P, Machnicka MA, Purta E, et al. MODOMICS: a database of RNA modification pathways. 2017 update. Nucleic Acids Res 2018;46(D1):D303–D307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gilbert WV, Bell TA, Schaening C. Messenger RNA modifications: form, distribution, and function. Science 2016;352(6292):1408–1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Plotch SJ, Bouloy M, Krug RM. Transfer of 5′-terminal cap of globin mRNA to influenza viral complementary RNA during transcription in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1979;76(4):1618–1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Daffis S, Szretter KJ, Schriewer J, et al. 2'-O methylation of the viral mRNA cap evades host restriction by IFIT family members. Nature 2010;468(7322):452–456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gokhale NS, McIntyre ABR, McFadden MJ, et al. N6-Methyladenosine in Flaviviridae viral RNA genomes regulates infection. Cell Host Microbe 2016;20(5):654–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Williams GD, Gokhale NS, Horner SM. Regulation of viral infection by the RNA modification N6-methyladenosine. Annu Rev Virol 2019;6(1):235–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pestova TV, Kolupaeva VG, Lomakin IB, et al. Molecular mechanisms of translation initiation in eukaryotes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001;98(13):7029–7036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cho EJ, Takagi T, Moore CR, et al. mRNA capping enzyme is recruited to the transcription complex by phosphorylation of the RNA polymerase II carboxy-terminal domain. Genes Dev 1997;11(24):3319–3326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McCracken S, Fong N, Rosonina E, et al. 5'-capping enzymes are targeted to pre-mRNA by binding to the phosphorylated carboxy-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II. Genes Dev 1997;11(24):3306–3318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chu C, Das K, Tyminski JR, et al. Structure of the guanylyltransferase domain of human mRNA capping enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011;108(25):10104–10108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Devarkar SC, Wang C, Miller MT, et al. Structural basis for m7G recognition and 2'-O-methyl discrimination in capped RNAs by the innate immune receptor RIG-I. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016;113(3):596–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Richter JD, Sonenberg N. Regulation of cap-dependent translation by eIF4E inhibitory proteins. Nature 2005;433(7025):477–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rhoads RE, Joshi B, Minich WB. Participation of initiation factors in the recruitment of mRNA to ribosomes. Biochimie 1994;76(9):831–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schlee M, Hartmann G. Discriminating self from non-self in nucleic acid sensing. Nat Rev Immunol 2016;16(9):566–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Decroly E, Ferron F, Lescar J, et al. Conventional and unconventional mechanisms for capping viral mRNA. Nat Rev Microbiol 2011;10(1):51–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McGeoch D, Fellner P, Newton C. Influenza virus genome consists of eight distinct RNA species. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1976;73(9):3045–3049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Krug RM, Morgan MA, Shatkin AJ. Influenza viral mRNA contains internal N6-methyladenosine and 5′-terminal 7-methylguanosine in cap structures. J Virol 1976;20(1):45–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Herz C, Stavnezer E, Krug R, et al. Influenza virus, an RNA virus, synthesizes its messenger RNA in the nucleus of infected cells. Cell 1981;26(3 Pt 1):391–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Moss B, Gershowitz A, Wei C-M, et al. Formation of the guanylylated and methylated 5′-terminus of vaccinia virus mRNA. Virology 1976;72(2):341–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Furuichi Y, Muthukrishnan S, Tomasz J, et al. Mechanism of formation of reovirus mRNA 5′-terminal blocked and methylated sequence, m7GpppGmpC. J Biol Chem 1976;251(16):5043–5053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Te Velthuis AJ, Fodor E. Influenza virus RNA polymerase: insights into the mechanisms of viral RNA synthesis. Nat Rev Microbiol 2016;14(8):479–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shuman S, Hurwitz J. Mechanism of mRNA capping by vaccinia virus guanylyltransferase: characterization of an enzyme--guanylate intermediate. Proc Natl Acad Sci 1981;78(1):187–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Plotch SJ, Tomasz J, Krug RM. Absence of detectable capping and methylating enzymes in influenza virions. J Virol 1978;28(1):75–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kobayashi M, Toyoda T, Ishihama A. Influenza virus PB1 protein is the minimal and essential subunit of RNA polymerase. Arch Virol 1996;141(3–4):525–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dias A, Bouvier D, Crepin T, et al. The cap-snatching endonuclease of influenza virus polymerase resides in the PA subunit. Nature 2009;458(7240):914–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Guilligay D, Tarendeau F, Resa-Infante P, et al. The structural basis for cap binding by influenza virus polymerase subunit PB2. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2008;15(5):500–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bouloy M, Plotch SJ, Krug RM. Globin mRNAs are primers for the transcription of influenza viral RNA in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1978;75(10):4886–4890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Omoto S, Speranzini V, Hashimoto T, et al. Characterization of influenza virus variants induced by treatment with the endonuclease inhibitor baloxavir marboxil. Sci Rep 2018;8(1):1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sikora D, Rocheleau L, Brown EG, et al. Influenza A virus cap-snatches host RNAs based on their abundance early after infection. Virology 2017;509:167–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gu W, Gallagher GR, Dai W, et al. Influenza A virus preferentially snatches noncoding RNA caps. RNA 2015;21(12):2067–2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rialdi A, Hultquist J, Jimenez-Morales D, et al. The RNA exosome syncs IAV-RNAPII transcription to promote viral ribogenesis and infectivity. Cell 2017;169(4):679–92 e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Barrows NJ, Campos RK, Liao KC, et al. Biochemistry and molecular biology of flaviviruses. Chem Rev 2018;118(8):4448–4482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wei CM, Gershowitz A, Moss B. Methylated nucleotides block 5′ terminus of HeLa cell messenger RNA. Cell 1975;4(4):379–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wei CM, Moss B. Methylated nucleotides block 5′-terminus of vaccinia virus messenger RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1975;72(1):318–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ramanathan A, Robb GB, Chan SH. mRNA capping: biological functions and applications. Nucleic Acids Res 2016;44(16):7511–7526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Haline-Vaz T, Silva TC, Zanchin NI. The human interferon-regulated ISG95 protein interacts with RNA polymerase II and shows methyltransferase activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2008;372(4):719–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Belanger F, Stepinski J, Darzynkiewicz E, et al. Characterization of hMTr1, a human Cap1 2'-O-ribose methyltransferase. J Biol Chem 2010;285(43):33037–33044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Williams GD, Gokhale NS, Snider DL, et al. The mRNA Cap 2'-O-methyltransferase CMTR1 regulates the expression of certain interferon-stimulated genes. mSphere 2020;5(3):e00202–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Habjan M, Hubel P, Lacerda L, et al. Sequestration by IFIT1 impairs translation of 2'O-unmethylated capped RNA. PLoS Pathog 2013;9(10):e1003663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zust R, Cervantes-Barragan L, Habjan M, et al. Ribose 2'-O-methylation provides a molecular signature for the distinction of self and non-self mRNA dependent on the RNA sensor Mda5. Nat Immunol 2011;12(2):137–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tsukiyama-Kohara K, Iizuka N, Kohara M, et al. Internal ribosome entry site within hepatitis C virus RNA. J Virol 1992;66(3):1476–1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hyde JL, Gardner CL, Kimura T, et al. A viral RNA structural element alters host recognition of nonself RNA. Science 2014;343(6172):783–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cleaves GR, Dubin DT. Methylation status of intracellular dengue type 2 40 S RNA. Virology 1979;96(1):159–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wengler G, Wengler G, Gross HJ. Studies on virus-specific nucleic acids synthesized in vertebrate and mosquito cells infected with flaviviruses. Virology 1978;89(2):423–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Koonin EV. Computer-assisted identification of a putative methyltransferase domain in NS5 protein of flaviviruses and λ2 protein of reovirus. J Gen Virol 1993;74(4):733–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Egloff MP, Benarroch D, Selisko B, et al. An RNA cap (nucleoside-2'-O-)-methyltransferase in the flavivirus RNA polymerase NS5: crystal structure and functional characterization. EMBO J 2002;21(11):2757–2768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ray D, Shah A, Tilgner M, et al. West nile virus 5 '-cap structure is formed by sequential guanine N-7 and ribose 2'-O methylations by nonstructural protein 5. J Virol 2006;80(17):8362–8370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Issur M, Geiss BJ, Bougie I, et al. The flavivirus NS5 protein is a true RNA guanylyltransferase that catalyzes a two-step reaction to form the RNA cap structure. RNA 2009;15(12):2340–2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zhou Y, Ray D, Zhao Y, et al. Structure and function of flavivirus NS5 methyltransferase. J Virol 2007;81(8):3891–3903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wengler G, Wengler G. The NS 3 nonstructural protein of flaviviruses contains an RNA triphosphatase activity. Virology 1993;197(1):265–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Szretter KJ, Daniels BP, Cho H, et al. 2'-O methylation of the viral mRNA cap by West Nile virus evades ifit1-dependent and -independent mechanisms of host restriction in vivo. PLoS Pathog 2012;8(5):e1002698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Dong H, Chang DC, Hua MH, et al. 2'-O methylation of internal adenosine by flavivirus NS5 methyltransferase. PLoS Pathog 2012;8(4):e1002642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Martin B, Coutard B, Guez T, et al. The methyltransferase domain of the Sudan ebolavirus L protein specifically targets internal adenosines of RNA substrates, in addition to the cap structure. Nucleic Acids Res 2018;46(15):7902–7912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ringeard M, Marchand V, Decroly E, et al. FTSJ3 is an RNA 2′-O-methyltransferase recruited by HIV to avoid innate immune sensing. Nature 2019;565(7740):500–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Elliott BA, Ho HT, Ranganathan SV, et al. Modification of messenger RNA by 2'-O-methylation regulates gene expression in vivo. Nat Commun 2019;10(1):3401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Iwanami Y, Brown GM. Methylated bases of ribosomal ribonucleic acid from HeLa cells. Arch Biochem Biophys 1968;126(1):8–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Saneyoshi M, Harada F, Nishimura S. Isolation and characterization of N6-methyladenosine from Escherichia coli valine transfer RNA. Biochim Biophys Acta 1969;190(2):264–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wei C-M, Moss B. Nucleotide sequences at the N6-methyladenosine sites of HeLa cell messenger ribonucleic acid. Biochemistry 1977;16(8):1672–1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Beemon K, Keith J. Localization of N6-methyladenosine in the Rous sarcoma virus genome. J Mol Biol 1977;113(1):165–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Bokar JA, Shambaugh ME, Polayes D, et al. Purification and cDNA cloning of the AdoMet-binding subunit of the human mRNA (N6-adenosine)-methyltransferase. RNA 1997;3(11):1233–1247. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Ping XL, Sun BF, Wang L, et al. Mammalian WTAP is a regulatory subunit of the RNA N6-methyladenosine methyltransferase. Cell Res 2014;24(2):177–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Liu J, Yue Y, Han D, et al. A METTL3-METTL14 complex mediates mammalian nuclear RNA N6-adenosine methylation. Nat Chem Biol 2014;10(2):93–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Moindrot B, Cerase A, Coker H, et al. A pooled shRNA screen identifies Rbm15, Spen, and Wtap as factors required for Xist RNA-mediated silencing. Cell Rep 2015;12(4):562–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Knuckles P, Lence T, Haussmann IU, et al. Zc3h13/Flacc is required for adenosine methylation by bridging the mRNA-binding factor Rbm15/Spenito to the m(6)A machinery component Wtap/Fl(2)d. Genes Dev 2018;32(5–6):415–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Scholler E, Weichmann F, Treiber T, et al. Interactions, localization, and phosphorylation of the m(6)A generating METTL3-METTL14-WTAP complex. RNA 2018;24(4):499–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Slobodin B, Han R, Calderone V, et al. Transcription impacts the efficiency of mRNA translation via co-transcriptional N6-adenosine methylation. Cell 2017;169(2):326–337e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Meyer KD, Saletore Y, Zumbo P, et al. Comprehensive analysis of mRNA methylation reveals enrichment in 3' UTRs and near stop codons. Cell 2012;149(7):1635–1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Dominissini D, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, Schwartz S, et al. Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature 2012;485(7397):201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Garcias Morales D, Reyes JL. A birds'-eye view of the activity and specificity of the mRNA m(6)A methyltransferase complex. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 2020;12:e1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Jia G, Fu Y, Zhao X, et al. N6-methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nat Chem Biol 2011;7(12):885–887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Zheng G, Dahl JA, Niu Y, et al. ALKBH5 is a mammalian RNA demethylase that impacts RNA metabolism and mouse fertility. Mol Cell 2013;49(1):18–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Zhu T, Roundtree IA, Wang P, et al. Crystal structure of the YTH domain of YTHDF2 reveals mechanism for recognition of N6-methyladenosine. Cell Res 2014;24(12):1493–1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Wang X, Lu Z, Gomez A, et al. N6-methyladenosine-dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature 2014;505(7481):117–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Liu N, Dai Q, Zheng G, et al. N(6)-methyladenosine-dependent RNA structural switches regulate RNA-protein interactions. Nature 2015;518(7540):560–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Wang X, Zhao BS, Roundtree IA, et al. N(6)-methyladenosine modulates messenger RNA translation efficiency. Cell 2015;161(6):1388–1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Du H, Zhao Y, He J, et al. YTHDF2 destabilizes m(6)A-containing RNA through direct recruitment of the CCR4-NOT deadenylase complex. Nat Commun 2016;7:12626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Shi H, Wang X, Lu Z, et al. YTHDF3 facilitates translation and decay of N(6)-methyladenosine-modified RNA. Cell Res 2017;27(3):315–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Li A, Chen YS, Ping XL, et al. Cytoplasmic m(6)A reader YTHDF3 promotes mRNA translation. Cell Res 2017;27(3):444–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Xiao W, Adhikari S, Dahal U, et al. Nuclear m(6)A reader YTHDC1 regulates mRNA splicing. Mol Cell 2016;61(4):507–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Shi H, Liu B, Nussbaumer F, et al. NMR chemical exchange measurements reveal that N(6)-methyladenosine slows RNA annealing. J Am Chem Soc 2019;141(51):19988–19993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Lu M, Zhang Z, Xue M, et al. N(6)-methyladenosine modification enables viral RNA to escape recognition by RNA sensor RIG-I. Nat Microbiol 2020;5(4):584–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Chen J, Jin L, Wang Z, et al. N6-methyladenosine regulates PEDV replication and host gene expression. Virology 2020;548:59–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Perlman S, Netland J. Coronaviruses post-SARS: update on replication and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol 2009;7(6):439–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Hao H, Hao S, Chen H, et al. N6-methyladenosine modification and METTL3 modulate enterovirus 71 replication. Nucleic Acids Res 2019;47(1):362–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Gokhale NS, McIntyre ABR, Mattocks MD, et al. Altered m(6)A modification of specific cellular transcripts affects Flaviviridae infection. Mol Cell 2020;77(3):542–55 e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. McIntyre W, Netzband R, Bonenfant G, et al. Positive-sense RNA viruses reveal the complexity and dynamics of the cellular and viral epitranscriptomes during infection. Nucleic Acids Res 2018;46(11):5776–5791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Pendleton KE, Chen B, Liu K, et al. The U6 snRNA m(6)A methyltransferase METTL16 regulates SAM synthetase intron retention. Cell 2017;169(5):824–35 e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Tran N, Ernst FGM, Hawley BR, et al. The human 18S rRNA m6A methyltransferase METTL5 is stabilized by TRMT112. Nucleic Acids Res 2019;47(15):7719–7733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]