Abstract

Aggregates of misfolded α-synuclein are a distinctive feature of Parkinson’s disease. Small oligomers of α-synuclein are thought to be an important neurotoxic agent, and α-synuclein aggregates exhibit prion-like behavior, propagating misfolding between cells. α-Synuclein is internalized by both passive diffusion and active uptake mechanisms, but how uptake varies with the size of the oligomer is less clear. We explored how α-synuclein internalization into live SH-SY5Y cells varied with oligomer size by comparing the uptake of fluorescently labeled monomers to that of engineered tandem dimers and tetramers. We found that these α-synuclein constructs were internalized primarily through endocytosis. Oligomer size had little effect on their internalization pathway, whether they were added individually or together. Measurements of co-localization of the α-synuclein constructs with fluorescent markers for early endosomes and lysosomes showed that most of the α-synuclein entered endocytic compartments, in which they were probably degraded. Treatment of the cells with the Pitstop inhibitor suggested that most of the oligomers were internalized by the clathrin-mediated pathway.

Significance

The protein α-synuclein aggregates in neurons in Parkinson’s disease, and misfolded aggregates can spread within and between cells in a prion-like way. Understanding how α-synuclein is taken up into cells is an important part of understanding propagation among cells. We explored how small α-synuclein oligomers are internalized to test for any size dependence in the uptake pathway and determine where the proteins end up in the cell. Uptake was dominated by endocytosis, with most molecules entering endocytic compartments where they could be degraded. This work shows that oligomers enter cells primarily through active transport with larger oligomers more dependent on clathrin-mediated endocytosis.

Introduction

The formation of aggregates of misfolded proteins is a neuropathological hallmark of many neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and Parkinson’s disease (1, 2, 3). Such aggregates can potentially disrupt cell signaling (4), result in cell apoptosis (5), and be neurotoxic (6). In the case of Parkinson’s disease, this misfolding is manifested in Lewy bodies (7), fibrillar aggregates consisting primarily of misfolded α-synuclein, a protein that is enriched in neurons (8,9). Several point mutations leading to more-easily misfolded forms of α-synuclein are among the mutations associated with familial Parkinson’s disease. Misfolded α-synuclein is neurotoxic both in vitro and in vivo (10, 11, 12, 13), but small oligomeric forms may be the most important for disease (14,15), acting as seeds to accelerate misfolding and aggregation (16, 17, 18), enhancing neurotoxicity in vivo (19) and in vitro (20), causing mitochondrial damage (21) and lysosome dysfunction (22), and leading to dysregulated calcium inflow into cells (23). Because of the role of α-synuclein in Parkinson’s disease, the development of novel molecular and pharmacological chaperones for inhibiting aggregation has been sought as a therapeutic strategy (24, 25, 26).

A remarkable property of misfolded α-synuclein is that it can show prion-like behavior, converting native α-synuclein to propagate misfolding within and between cells (27,28). Understanding how α-synuclein oligomers are taken up into cells is thus essential. Previous work has found that α-synuclein can enter cells by passive transport, specifically diffusion across the membrane, simply via interactions with membrane lipid and proteins (29,30). It can also enter cells actively by endocytosis (31, 32, 33, 34), whereby material is engulfed from the extracellular environment (for example, by clathrin-mediated endocytosis (35)), ending up in endosomes and ultimately lysosomes (36,37). α-Synuclein localized to lysosomes has been found to be released from cells via exocytosis, permitting re-uptake by neighboring cells and propagation of misfolding (38, 39, 40). Even though internalization by both diffusion and endocytosis has been observed for monomers and larger oligomeric aggregates, it is unclear whether the uptake differs for monomers and small oligomers of different sizes.

To understand better those factors that may affect prion-like propagation of α-synuclein, here we explore whether the internalization pathways of monomers and small oligomers of α-synuclein differ, the degree to which they are taken up together, and the extent of co-localization with endocytic compartments in the cells. To study small oligomers of controlled size, we used engineered tandem-repeat proteins consisting of multiple repeats of the monomeric form of the protein connected head-to-tail by short peptide linkers and expressed as a single polypeptide (41). Such tandem oligomers have been used previously to study small oligomers of numerous aggregation-prone proteins, including aβ (42,43), PrP (44,45), SH3 (46,47), and α-synuclein (48), as they provide one of the few means of studying very small oligomers under controlled conditions. We imaged the distribution of α-synuclein monomers, dimers, and tetramers internalized by live SH-SY5Y cells, exploring the time-dependent behavior after internalization. We imaged pairs of constructs added simultaneously to determine whether they follow similar fates. We probed the co-localization of oligomers with markers for early endosomes and lysosomes to determine if α-synuclein oligomers are found there. Finally, we studied the uptake of α-synuclein oligomers in cells pretreated with an inhibitor of clathrin-mediated endocytosis to determine whether this uptake pathway is dominant.

Materials and methods

α-Synuclein constructs

Monomers of α-synuclein (denoted as αS-1), as well as tandem dimers (denoted as αS-2) and tetramers (denoted as αS-4) in which monomer units were connected head-to-tail by tripeptide GSG linkers, were expressed and purified as described previously (41). Each construct contained a Cys residue added to the C-terminus, which was used to functionalize the proteins with fluorescent dyes (Oregon Green 488, Cy3, or Cy5), as described previously (48). For cellular uptake experiments, labeled α-synuclein constructs were prepared in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to the desired concentration.

SH-SY5Y cell culture

Human bone marrow neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were cultured in a 1:1 mixture of F-12K and Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen). Cells were grown at 37°C and 5% CO2 in an incubator. At 80% cell surface confluence (7–10 days), cells were passaged at 1:5 dilution, using 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA, onto 35-mm glass-bottom dishes and incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for another 4–5 days until 60% cell confluency was reached. 1 mL of media was replaced in each dish every day until experiments were begun after reaching 60% confluency.

Continuous exposure of live cells

At 60% cell surface confluency, cells were exposed to 100 μL of 8 μM monomer-equivalent concentrations of the α-synuclein constructs (8 μM for αS-1, 4 μM for αS-2, and 2 μM for αS-4) in 1 mL with fresh culture media. These concentrations were chosen to have equivalent masses of protein in each case, ensuring that differences in uptake were not driven by differences in the mass of protein being imported and to be consistent with previous studies of aggregation of these protein constructs. Cells were exposed to unseeded α-synuclein constructs for 2 h and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2. The cells were then washed at room temperature with PBS, fixed in 1 mL 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) at room temperature for 10 min, and washed with PBS for a final time before imaging.

Pulse-chase exposure of live cells

At 60% cell surface confluency, cells were exposed to 100 μL of 8 μM monomer-equivalent concentrations of the α-synuclein constructs in 1 mL of fresh culture media. Cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 2 h (“pulse” stage); then, the media containing α-synuclein was removed, the cells were washed with PBS, 1 mL of fresh media was added, and the cells were incubated for an additional 1, 2, 4, or 24 h (“chase” stage). After the chase incubation, the cells were washed at room temperature with PBS, fixed in 1 mL 4% PFA at room temperature for 10 min, and washed with PBS for a final time before imaging.

Simultaneous exposure to different constructs

Cells were exposed to 100 μL of one α-synuclein construct labeled with Cy3 and 100 μL of a second construct labeled with Cy5 (8-μM monomer-equivalent concentration in each case) in 1 mL of cell culture media and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 2 h. The cells were then washed with PBS, fixed with 1 mL of 4% PFA for 10 min at room temperature, and washed with PBS for a final time before imaging.

Co-localization of α-synuclein and endocytic compartments

The early endosomal and lysosomal compartments were labeled using antibodies specific to the protein markers Rab5 and LAMP-1, respectively (49). Monoclonal primary antibodies (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) from two different species (mouse and rat) were used, and polyclonal secondary antibodies (Abcam; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) labeled with fluorescent probes (Alexa Fluor 488, Cy3, and Alexa Fluor 555) were added to bind the primary antibodies. Cells were exposed to 100 μL of the desired α-synuclein construct at 8-μM monomer-equivalent concentration and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 2 h, and then washed with PBS and fixed with 1 mL 4% PFA for 10 min at room temperature. The cells were washed again with PBS and incubated with 1 mL of PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100 detergent at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 15 min to permeabilize the cell membrane so that antibodies could access the intracellular compartments. The cells were then removed from the incubator, washed with PBS, and incubated for 1 h (with 100 μL of 3% bovine serum albumin in PBS to prevent nonspecific intracellular binding of antibodies upon labeling). The cells were next washed with PBS, labeled with the primary antibody (diluted 100-fold in PBS) by adding 100 μL of the primary antibody and incubating overnight at 4°C, washed again with PBS, and incubated with the secondary antibody (diluted 500-fold in PBS) for 90 min at room temperature. Cells were then washed with PBS before imaging.

Endocytic uptake inhibition

At 60% cell surface confluency, cells were exposed to 20 μM Pitstop, a clathrin-mediated endocytosis inhibitor (50), incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 30 min, and then washed at room temperature with PBS. Cells were exposed to α-synuclein constructs for 2 h (8-μM monomer-equivalent concentration) and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2. The cells were then washed at room temperature with PBS, fixed in 1 mL 4% PFA at room temperature for 10 min, and washed with PBS for a final time before imaging.

Confocal microscopy imaging

Cells were imaged with a laser scanning confocal microscope (710; ZEISS, Oberkochen, Germany) with a 63 × 1.4 NA differential interference contrast (DIC) plan-apochromat lens. An argon-ion laser was used for excitation at 488 nm, a solid-state laser for excitation at 561 nm, and a HeNe laser for excitation at 633 nm. For all imaging, the detectors were set to detect wavelengths within specific ranges: 489–564 nm for excitation of Oregon Green, 561–620 nm for excitation of Cy3 and Alexa Fluor 555 probes, and 633–697 nm for excitation of Cy5 and Alexa Fluor 647. The pinhole was set to 1 Airy unit, pixel dwell time was 3.15 μs with an average of two line scans, and a zoom 14 was used to achieve a pixel size of ∼20 nm, ensuring oversampling by ∼10 pixels per beam width. Each image comprised 512 × 512 pixels, resulting in a 10 × 10-μm image for image correlation spectroscopy (ICS) analysis. For each measurement, 25–40 images were collected on different cells in the sample. For cells containing two fluorescent dyes and hence using two excitations wavelengths, the detectors were optimized to minimize cross talk between the channels, and their alignments were checked to ensure overlap of the illumination volumes.

ICS

Images were analyzed with ICS (51) to characterize the α-synuclein constructs within the cells. The normalized autocorrelation function, g(α, β), was obtained from the normalized intensity fluctuations, δIn(x, y), at different positions in the image:

| (1) |

where α and β represent spatial lags in the x and y axes, respectively, I is the fluorescence intensity, and the average is taken over the entire image for a given α and β. The amplitude g(0, 0) yielded the variance of the autocorrelation function (52); assuming an intensity proportional to the concentration of fluorescent species in clusters, g(0, 0) then provided an estimate of the average number of fluorescent clusters in the observation region, 〈NC〉, via

| (2) |

The average number of fluorescent particles per unit area or cluster density, CD, was found as

| (3) |

where ω is the beam radius. Finally, the average number of monomers per cluster or relative degree of aggregation, DA, was found from the product of the average intensity in the image and the autocorrelation amplitude:

| (4) |

where 〈NM〉 is the average number of fluorescence particles, and c is a constant reflecting the properties of the microscope system (e.g., emission collection efficiency) and fluorescent probe (e.g., quantum yield and molar adsorption coefficients) measured experimentally (51).

An extension of ICS for studying correlations between the intensities from two species labeled with different colors, image cross correlation spectroscopy (ICCS), was used to characterize co-localization of different α-synuclein species and of α-synuclein with the different endocytic compartments. Defining the autocorrelation amplitudes from each color as gR(0, 0) and gG(0, 0) (for colors R and G) and the cross correlation amplitude as gRG(0, 0), the average number of clusters containing species of both colors was found from

| (5) |

The extent of co-localization, expressed as the fraction of all clusters containing red species that also contained green species, fR|G, or the converse, fG|R, was then given by

| (6) |

For both ICS and ICCS analysis, ImageJ software was used to obtain the normalized auto- and cross correlation function amplitudes, the average intensity, and the laser beam width. Regions of interest (ROIs) were selected from the full images to ensure that the region analyzed was entirely within the cell.

Subpopulation intensity analysis

Internalization leads to two types of fluorescence within the image: high intensity regions (puncta of fluorescence) and low intensity regions (diffuse fluorescence). To determine whether these were affected differently by treatment with Pitstop, we calculated the average intensity for 0.142 μm2 (20 pixels × 20 pixels) ROIs, corresponding to fluorescence arising from different regions of the cell. The ROIs were chosen to measure within regions of diffuse fluorescence, puncta, and dark regions considered background. Four ROIs were measured for each type of fluorescence (12 square regions total) in one cell and averaged to yield one value for each fluorescence type in that cell. The background fluorescence intensity was subtracted from the puncta and diffuse fluorescence intensities. This analysis was repeated for 10 cells in each sample and averaged to yield the final background-corrected intensities values for puncta and diffuse fluorescence.

Results and discussion

α-Synuclein constructs are internalized by live cells

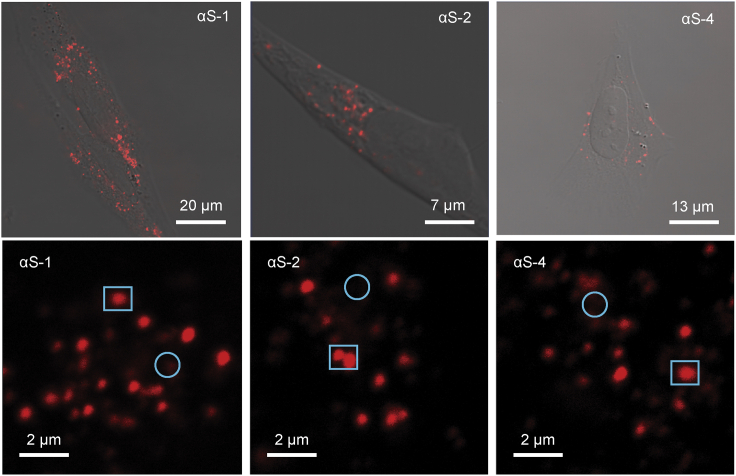

To test the extent to which α-synuclein monomers (αS-1), tandem dimers (αS-2), and tandem tetramers (αS-4) could be internalized, we exposed live SH-SY5Y cells to each of the Cy5-labeled α-synuclein constructs for 2 h before fixing the cells for imaging. Examining fluorescence and DIC images of a whole cell (Fig. 1, top row), the overlap of these two images suggested that the brightest fluorescence was found in intracellular vesicular compartments. Images at higher magnification images (Fig. 1, bottom row) showed that for each of the α-synuclein constructs, most of the fluorescence was in distinct puncta within the cells, suggesting internalization into distinct compartments, but some appeared as a diffuse background, suggesting distribution within the cytosol. There were no immediately apparent differences between the behavior of αS-1, αS-2, and αS-4; each construct had a similar distribution within the cells, suggesting that internalization of the small oligomers does not differ qualitatively from that of monomers.

Figure 1.

Uptake of α-synuclein constructs by live SH-SY5Y cells. Top row: representative low-magnification images of SH-SY5Y cells merging confocal fluorescence and DIC channels are shown. Cells were fixed after 2-h continuous exposure to Cy-5-labeled αS-1, αS-2, and αS-4. Bottom row: representative higher-resolution images showing punctate (squares) and diffuse (circles) distributions of fluorescence from αS-1, αS-2, and αS-4 are shown. To see this figure in color, go online.

To obtain a more quantitative assessment of the uptake of the different constructs, we analyzed 20–30 images from different cells by ICS (see Materials and methods). ICS monitors spatial fluctuations of the fluorescence intensity within images, allowing properties like the number and density of clusters and the degree of aggregation to be determined (53, 54, 55, 56, 57). We found that the average total intensity for the three constructs was similar in magnitude, varying by only ∼10% (ranging from 167 to 186 fluorescence units), suggesting that they were all internalized to a similar extent within the 2-h period studied. The autocorrelation amplitude for each construct was also quite similar, revealing that there were a similar number of clusters present in each case (cluster density of 0.8–1.2/μm2). Likewise, the degree of aggregation (average number of molecules per cluster) was similar for all constructs at ∼300–500 molecules per cluster.

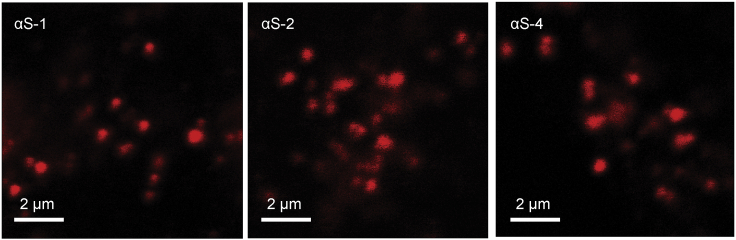

Distribution of α-synuclein varies with time

We next examined the α-synuclein construct distributions over time using pulse-chase experiments to determine their fate. In these experiments, the extracellular α-synuclein was rinsed off the cells after 2 h of exposure, but the cells were not fixed and imaged until a variable amount of time had elapsed (a chase duration of 1–24 h). Representative images taken after a 2-h chase before cell fixation (Fig. 2) showed no qualitative difference from the images taken without a chase time before fixation (Fig. 1). However, some trends were evident at longer chase times relative to 1 h (Fig. 3) when 20–30 images of each were analyzed by ICS. This analysis provides information about the possible stability through the intensity analysis and the distribution through the cluster density analysis. At 24 h, the total fluorescence intensity had decreased for αS-1 and αS-2 (p < 0.01) but not αS-4, possibly because of degradation of the smaller constructs. The cluster density appeared to increase (with a corresponding decrease in the degree of aggregation) for αS-1 and αS-2 after 24 h (p < 0.01), consistent with dispersal of the fluorescence into a larger number of smaller compartments. Little change was apparent in either the intensity or the cluster density for αS-4 at 24 h (p > 0.05), suggesting that the larger construct may be slightly more resistant to degradation.

Figure 2.

Pulse-chase exposure of live cells to α-synuclein. Each image shows one SH-SY5Y cell that was fixed 2 h after rinsing off Cy-5-labeled αS-1, αS-2, or αS-4, to which the cells were exposed for 2 h. To see this figure in color, go online.

Figure 3.

Change in ICS parameters with chase time. (A) Change in fluorescence intensity (amount of internalized protein) as a function of chase time is shown. (B) Change in cluster density is shown. (C) Change in degree of aggregation is shown. Error bars show SEM. All statistically significant (95% confidence level) differences from results at 1 h are indicated with asterisks. Shown are αS-1 (black), αS-2 (red), and αS-4 (cyan). To see this figure in color, go online.

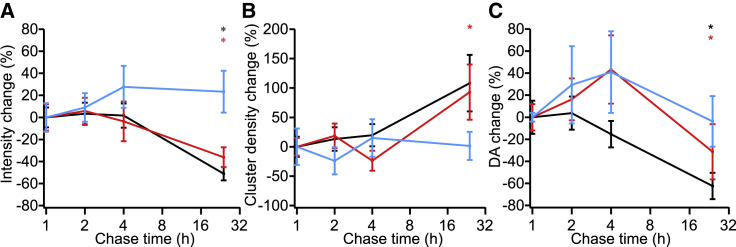

Uptake distribution does not depend on oligomer size

To test if the different α-synuclein constructs were taken up into the same intracellular compartments, we imaged cells exposed simultaneously to two different constructs and tracked the co-localization of the two constructs. Representative images of cells exposed to different pairs of constructs for 2 h before immediate fixation (Fig. 4) showed extensive co-localization of the different constructs within the same compartments, seen as yellow or orange puncta in the images. To quantify the extent of co-localization, we used ICCS analysis for every possible pair of constructs to calculate the average fraction of clusters containing construct αS-i that also contained construct αS-j, denoted as fαS-i|αS-j (Table 1). We found that the extent of co-localization was at or close to 100% in almost all cases, indicating that when two different oligomers were presented to the cells simultaneously, they were almost always taken up together. This result suggests that the uptake pathway for all constructs led to the same intracellular compartments.

Figure 4.

Simultaneous uptake of different α-synuclein constructs by live cells. Shown are images of cells that were fixed after 2-h exposure to αS-1 and αS-2, αS-1 and αS-4, or αS-2 and αS-4. Each image shows one SH-SY5Y cell. Shown are smaller construct (red) and larger construct (green). To see this figure in color, go online.

Table 1.

Fractional co-localization ofα-synuclein constructs

| fαS-1|αS-2 | 0.79 ± 0.07 | fαS-2|αS-1 | 1.00 ± 0.04 |

| fαS-1|αS-4 | 0.93 ± 0.03 | fαS-4|αS-1 | 0.98 ± 0.04 |

| fαS-2|αS-4 | 1.00 ± 0.01 | fαS-4|αS-2 | 1.00 ± 0.01 |

Error represents SEM.

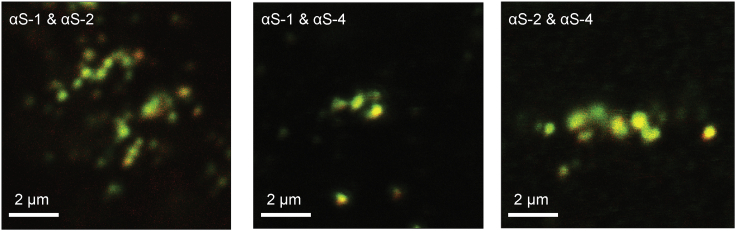

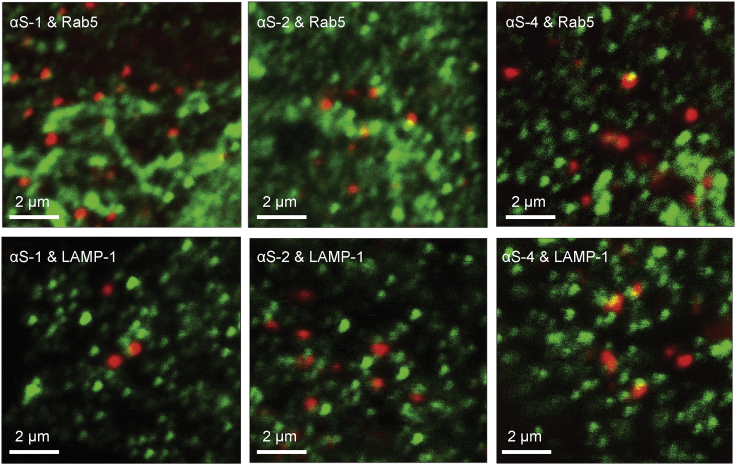

Internalized α-synuclein co-localizes with endocytic compartments

The largely punctate distribution of the internalized α-synuclein constructs suggested that they might have been taken up into endocytic compartments. To confirm that the constructs were captured in the endocytic pathway, we tested for co-localization with early endosomes and lysosomes using fluorescently tagged protein markers believed to be specific to each compartment: Rab5 for early endosomes and LAMP-1 for lysosomes. Representative images of cells exposed to one of αS-1, αS-2, or αS-4 and tagged for either Rab5 (Fig. 5, top) or LAMP-1 (Fig. 5, bottom) showed at first glance only modest qualitative evidence of localization of α-synuclein in early endosomes and lysosomes, because many of the green puncta (reflecting the endosomal compartments) had little overlap with the red puncta (reflecting the internalized protein).

Figure 5.

Co-localization of α-synuclein with markers of endocytic compartments after uptake by live cells. Images of cells that were fixed after 2-h exposure to αS-1, αS-2, or αS-4. Rab5 (top) and LAMP-1 (bottom) markers shown in green and α-synuclein in red. Each image shows one SH-SY5Y cell. To see this figure in color, go online.

To quantify the co-localization, we used ICCS to calculate the average fraction of α-synuclein clusters contained in early endosomes and lysosomes, respectively fαS-i|Rab5 and fαS-i|LAMP-1, as well as the fraction of early endosomes and lysosomes containing α-synuclein, respectively fRab5|αS-i and fLAMP-1|αS-i (Table 2). These calculations revealed that ∼40–60% of the α-synuclein clusters were associated with Rab5-marked compartments, and another 35–45% were associated with compartments marked with LAMP-1. Because there is some overlap of Rab5 and LAMP-1 makers (58), the total fraction of α-synuclein localized in endocytic compartments is somewhat less than the sum of the results for Rab5 and LAMP-1 individually. Nevertheless, it is clear that the majority of the α-synuclein molecules present in the cells were localized to these endocytic compartments. However, only a small fraction (under 10%) of all the compartments marked with Rab5 or LAMP-1 contained α-synuclein, accounting for the initial impression of only modest co-localization in the images. These results indicate that the active uptake involved endocytic pathways (e.g., clathrin- or caveolin-mediated endocytosis), leading to associations with endocytic compartments like early endosomes and lysosomes. The minority of internalized α-synuclein not co-localizing with either the early endosomes or lysosomes was presumably either present in the diffuse fraction or possibly localized in the late endosomes.

Table 2.

Fractional co-localization of α-synuclein constructs with early endosomes and lysosomes

| fαS-1|Rab5 | 0.58 ± 0.09 | fRab5|αS-1 | 0.08 ± 0.02 |

| fαS-2|Rab5 | 0.41 ± 0.07 | fRab5|αS-2 | 0.06 ± 0.01 |

| fαS-4|Rab5 | 0.45 ± 0.07 | fRab5|αS-4 | 0.07 ± 0.01 |

| fαS-1|LAMP-1 | 0.35 ± 0.07 | fLAMP-1|αS-1 | 0.10 ± 0.02 |

| fαS-2|LAMP-1 | 0.42 ± 0.08 | fLAMP-1|αS-2 | 0.07 ± 0.01 |

| fαS-4|LAMP-1 | 0.45 ± 0.07 | fLAMP-1|αS-4 | 0.07 ± 0.03 |

Errors represent SEM.

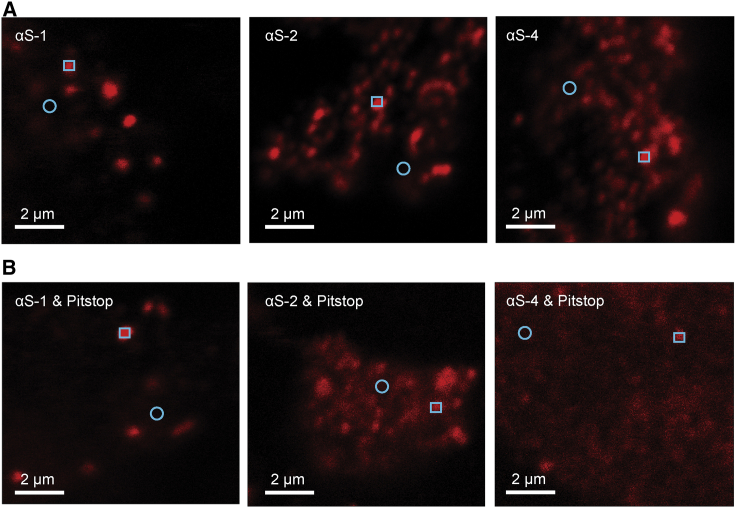

Internalization of α-synuclein constructs can be inhibited

Finally, we sought to determine if inhibition of clathrin-mediated endocytosis by Pitstop (50) affects the internalization of the α-synuclein constructs. Cells incubated with Pitstop for 30 min before 2 h of exposure to dye-labeled α-synuclein were washed, fixed, and imaged by confocal fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 6). The fluorescence intensities in these images suggested qualitatively that cells pretreated with Pitstop contained lower levels of α-synuclein overall than untreated cells, indicating that Pitstop suppressed the internalization to some extent.

Figure 6.

Effect of Pitstop on oligomer uptake. (A) Shown are untreated cells exposed to constructs for 2 h and then fixed before imaging. (B) Cells pretreated with Pitstop before 2-hr incubation with constructs showed less fluorescence. Punctate and diffuse distribution of fluorescence shown with square and circles, respectively. To see this figure in color, go online.

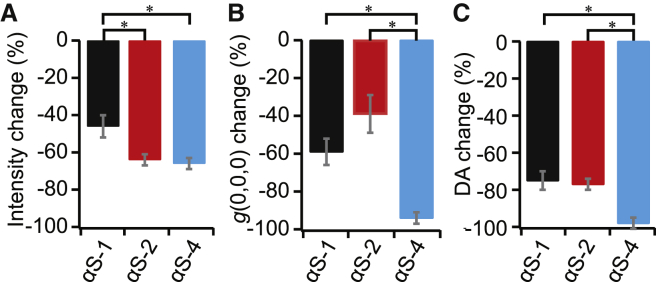

To obtain a more quantitative assessment of the effect of Pitstop on the extent of internalization, we used ICS to compare the average total intensities, the autocorrelation amplitudes, and degree of aggregation for each construct (Fig. 7). Pitstop was seen to decrease the fluorescence intensity, the autocorrelation amplitude, and the degree of aggregation in all cases but to varying degrees. The average total intensities in the images of the three constructs in cells pretreated with Pitstop decreased by about half for αS-1 and by about two-thirds for αS-2, and αS-4 (Fig. 7 A), suggesting that at least half of the internalization occurred via the clathrin-mediated pathway. The autocorrelation amplitudes also decreased in the presence of Pitstop in all cases (Fig. 7 B), indicating that there were fewer large clusters within the cells, and correspondingly, the degree of aggregation decreased significantly. Interestingly, we observed a clear size dependence in the effect of Pitstop; the monomer was least sensitive to the treatment, whereas αS-4 was most sensitive. In all cases, there was still at least some internalization in the presence of Pitstop, suggesting that the protein was able to enter the cell through pathways other than clathrin-mediated endocytosis. However, the distribution within the cells was more diffuse, particularly for αS-4, suggesting that some of this residual fluorescence was within the cytosol rather than within compartments.

Figure 7.

ICS analysis of effects of Pitstop. The change in (A) intensity, (B) autocorrelation amplitude, and (C) degree of aggregation in cells treated with Pitstop to inhibit clathrin-mediated endocytosis compared with the results in cells without Pitstop treatment. Error bars show SEM. All statistically significant (95% confidence level) differences in results are indicated with asterisks. To see this figure in color, go online.

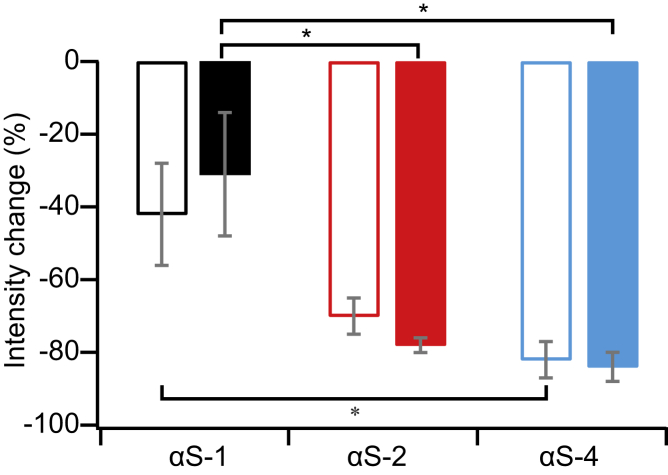

The observation that the residual fluorescence after Pitstop treatment was more diffuse and featured fewer clusters suggests that Pitstop differentially inhibited the uptake of material into the endosomes and lysosomes. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed how Pitstop treatment changed the fluorescence intensity seen in small ROIs containing either puncta of high fluorescence (clusters) or diffuse fluorescence. The decrease in fluorescence intensity was the same for both the regions containing puncta (Fig. 8, solid bars) and those containing just diffuse fluorescence (Fig. 8, open bars), indicating that Pitstop inhibited both populations to the same extent. The clusters were thus not inhibited more by Pitstop. As in the ICS analysis, the effect of the Pitstop was again much greater for the dimer and the tetramer compared to the monomer, revealing a size dependence in the inhibition process. We note that applying a similar analysis to regions of punctate and diffuse fluorescence in the images from the chase time experiments (Fig. 3) showed that the two subpopulations (punctate and diffuse) changed to the same extent over the time period of 24 h. These two populations were therefore likely not independent.

Figure 8.

Fluorescence intensity analysis of subpopulations. The change in fluorescence intensity upon treatment by Pitstop was the same in regions of diffuse (open bars) and punctate (solid bars) fluorescence but was smallest for αS-4 and largest for αS-4. Error bars show SEM. All statistically significant (95% confidence level) differences in results are indicated with asterisks. To see this figure in color, go online.

Conclusions

This work aimed at a better understanding of the factors that may affect the prion-like propagation of α-synuclein by studying the uptake and distribution of small oligomers using fluorescence imaging techniques. The discrete puncta observed in fluorescence images suggest localization of the α-synuclein to intracellular compartments, consistent with an active transport process like endocytosis. These results are consistent with previous work in which uptake of extracellular α-synuclein (monomers and larger oligomeric aggregates) was observed through receptor-mediated endocytosis (31). Indeed, the majority of the clusters were found to coincide with early endosomes or lysosomes, even though only a small fraction of these compartments contained significant amounts of proteins, consistent with previous work studying the association of α-synuclein with Rab5A and LAMP-1 (37,59). The observed co-localization of internalized monomers and oligomers indicates that they are all taken up by similar processes, and all are inhibited to varying degrees by Pitstop. This result is consistent with previous work showing suppression of α-synuclein uptake by endocytosis inhibitors (60, 61, 62, 63, 64) and supporting the conclusion that they are internalized to a large extent by clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Finally, the time evolution of the distribution of fluorescence suggests that there is some degradation of the proteins (40,65,66) and that the tetrameric construct is slightly more resistant to this process, which may be why higher oligomeric states are more infectious. These results are consistent with previous work showing that aggregated α-synuclein species (oligomers and fibrils) exhibited more pronounced accumulation within recipient cells than did monomers (59).

Author contributions

All authors designed the research. L.J.S. performed the research and analyzed the data. All authors wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Alberta Innovates, the Alberta Prion Research Institute, and the National Research Council Canada.

Footnotes

Editor: Christopher Yip.

References

- 1.Ross C.A., Poirier M.A. Protein aggregation and neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Med. 2004;10(Suppl):S10–S17. doi: 10.1038/nm1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Selkoe D.J. Cell biology of protein misfolding: the examples of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004;6:1054–1061. doi: 10.1038/ncb1104-1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wagner J., Ryazanov S., Giese A. Anle138b: a novel oligomer modulator for disease-modifying therapy of neurodegenerative diseases such as prion and Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;125:795–813. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1114-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang S., Xu B., Witt S.N. α-Synuclein disrupts stress signaling by inhibiting polo-like kinase Cdc5/Plk2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:16119–16124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206286109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gavrin L.K., Denny R.A., Saiah E. Small molecules that target protein misfolding. J. Med. Chem. 2012;55:10823–10843. doi: 10.1021/jm301182j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cookson M.R. α-Synuclein and neuronal cell death. Mol. Neurodegener. 2009;4:9. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-4-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuznetsov I.A., Kuznetsov A.V. What can trigger the onset of Parkinson’s disease - a modeling study based on a compartmental model of α-synuclein transport and aggregation in neurons. Math. Biosci. 2016;278:22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jakes R., Spillantini M.G., Goedert M. Identification of two distinct synucleins from human brain. FEBS Lett. 1994;345:27–32. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00395-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raghavan R., Kruijff Ld., White C.L., III Alpha-synuclein expression in the developing human brain. Pediatr. Dev. Pathol. 2004;7:506–516. doi: 10.1007/s10024-003-7080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Macchi F., Deleersnijder A., Baekelandt V. High-content analysis of α-synuclein aggregation and cell death in a cellular model of Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2016;261:117–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2015.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jensen P.H., Nielsen M.S., Goedert M. Binding of alpha-synuclein to brain vesicles is abolished by familial Parkinson’s disease mutation. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:26292–26294. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forloni G., Bertani I., Invernizzi R. α-synuclein and Parkinson’s disease: selective neurodegenerative effect of α-synuclein fragment on dopaminergic neurons in vitro and in vivo. Ann. Neurol. 2000;47:632–640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Da Pozzo E., La Pietra V., Greco G. p53 functional inhibitors behaving like pifithrin-β counteract the Alzheimer peptide non-β-amyloid component effects in human SH-SY5Y cells. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2014;5:390–399. doi: 10.1021/cn4002208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marques O., Outeiro T.F. Alpha-synuclein: from secretion to dysfunction and death. Cell Death Dis. 2012;3:e350. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2012.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vargas J.Y., Grudina C., Zurzolo C. The prion-like spreading of α-synuclein: from in vitro to in vivo models of Parkinson’s disease. Ageing Res. Rev. 2019;50:89–101. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2019.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soto C., Estrada L., Castilla J. Amyloids, prions and the inherent infectious nature of misfolded protein aggregates. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2006;31:150–155. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soto C., Estrada L.D. Protein misfolding and neurodegeneration. Arch. Neurol. 2008;65:184–189. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2007.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caruana M., Högen T., Vassallo N. Inhibition and disaggregation of α-synuclein oligomers by natural polyphenolic compounds. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:1113–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Winner B., Jappelli R., Riek R. In vivo demonstration that α-synuclein oligomers are toxic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:4194–4199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100976108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bisaglia M., Greggio E., Bubacco L. Alpha-synuclein overexpression increases dopamine toxicity in BE2-M17 cells. BMC Neurosci. 2010;11:41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-11-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Devi L., Raghavendran V., Anandatheerthavarada H.K. Mitochondrial import and accumulation of α-synuclein impair complex I in human dopaminergic neuronal cultures and Parkinson disease brain. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:9089–9100. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710012200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bourdenx M., Bezard E., Dehay B. Lysosomes and α-synuclein form a dangerous duet leading to neuronal cell death. Front. Neuroanat. 2014;8:83. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2014.00083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Danzer K.M., Haasen D., Kostka M. Different species of α-synuclein oligomers induce calcium influx and seeding. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:9220–9232. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2617-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friesen E.L., De Snoo M.L., Kalia S.K. Chaperone-based therapies for disease modification in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsons Dis. 2017;2017:5015307. doi: 10.1155/2017/5015307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bose S., Cho J. Targeting chaperones, heat shock factor-1, and unfolded protein response: promising therapeutic approaches for neurodegenerative disorders. Ageing Res. Rev. 2017;35:155–175. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2016.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalia L.V., Kalia S.K., Lang A.E. α-Synuclein oligomers and clinical implications for Parkinson disease. Ann. Neurol. 2013;73:155–169. doi: 10.1002/ana.23746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lema Tomé C.M., Tyson T., Brundin P. Inflammation and α-synuclein’s prion-like behavior in Parkinson’s disease--is there a link? Mol. Neurobiol. 2013;47:561–574. doi: 10.1007/s12035-012-8267-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bernis M.E., Babila J.T., Tamgüney G. Prion-like propagation of human brain-derived alpha-synuclein in transgenic mice expressing human wild-type alpha-synuclein. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2015;3:75. doi: 10.1186/s40478-015-0254-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fortin D.L., Troyer M.D., Edwards R.H. Lipid rafts mediate the synaptic localization of α-synuclein. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:6715–6723. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1594-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Auluck P.K., Caraveo G., Lindquist S. α-Synuclein: membrane interactions and toxicity in Parkinson’s disease. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2010;26:211–233. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.042308.113313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee H.J., Suk J.E., Lee S.J. Assembly-dependent endocytosis and clearance of extracellular α-synuclein. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2008;40:1835–1849. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee H.-J., Patel S., Lee S.J. Intravesicular localization and exocytosis of alpha-synuclein and its aggregates. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:6016–6024. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0692-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hansen C., Angot E., Brundin P. α-Synuclein propagates from mouse brain to grafted dopaminergic neurons and seeds aggregation in cultured human cells. J. Clin. Invest. 2011;121:715–725. doi: 10.1172/JCI43366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Desplats P., Lee H.-J., Lee S.J. Inclusion formation and neuronal cell death through neuron-to-neuron transmission of α-synuclein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:13010–13015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903691106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dikic I. Landes Bioscience and Springer Science + Business Media, LLC; New York: 2006. Endosomes. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Helenius A., Mellman I., Hubbard A. Endosomes. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1983;8:245–250. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Masaracchia C., Hnida M., Outeiro T.F. Membrane binding, internalization, and sorting of alpha-synuclein in the cell. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2018;6:79. doi: 10.1186/s40478-018-0578-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Delenclos M., Trendafilova T., McLean P.J. Investigation of endocytic pathways for the internalization of exosome-associated oligomeric alpha-synuclein. Front. Neurosci. 2017;11:172. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2017.00172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bliederhaeuser C., Grozdanov V., Danzer K.M. Age-dependent defects of alpha-synuclein oligomer uptake in microglia and monocytes. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:379–391. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1504-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Danzer K.M., Kranich L.R., McLean P.J. Exosomal cell-to-cell transmission of alpha synuclein oligomers. Mol. Neurodegener. 2012;7:42. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-7-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dong C., Hoffmann M., Woodside M.T. Structural characteristics and membrane interactions of tandem α-synuclein oligomers. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:6755. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-25133-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sengupta U., Nilson A.N., Kayed R. The role of amyloid-β oligomers in toxicity, propagation, and immunotherapy. EBioMedicine. 2016;6:42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mroczko B., Groblewska M., Lewczuk P. Amyloid β oligomers (AβOs) in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neural Transm. (Vienna) 2018;125:177–191. doi: 10.1007/s00702-017-1820-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gilch S., Wopfner F., Schätzl H.M. Polyclonal anti-PrP auto-antibodies induced with dimeric PrP interfere efficiently with PrPSc propagation in prion-infected cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:18524–18531. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210723200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu H., Dee D.R., Woodside M.T. Protein misfolding occurs by slow diffusion across multiple barriers in a rough energy landscape. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:8308–8313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1419197112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Orte A., Birkett N.R., Klenerman D. Direct characterization of amyloidogenic oligomers by single-molecule fluorescence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:14424–14429. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803086105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ruzafa D., Morel B., Conejero-Lara F. Characterization of oligomers of heterogeneous size as precursors of amyloid fibril nucleation of an SH3 domain: an experimental kinetics study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e49690. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li X., Dong C., Woodside M.T. Early stages of aggregation of engineered α-synuclein monomers and oligomers in solution. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:1734. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-37584-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mukherjee S., Ghosh R.N., Maxfield F.R. Endocytosis. Physiol. Rev. 1997;77:759–803. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.3.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dutta D., Williamson C.D., Donaldson J.G. Pitstop 2 is a potent inhibitor of clathrin-independent endocytosis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45799. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Petersen N.O., Brown C., Wiseman P.W. Analysis of membrane protein cluster densities and sizes in situ by image correlation spectroscopy. Faraday Discuss. 1998;111:289–305. doi: 10.1039/a806677i. discussion 331–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kolin D.L., Wiseman P.W. Advances in image correlation spectroscopy: measuring number densities, aggregation states, and dynamics of fluorescently labeled macromolecules in cells. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2007;49:141–164. doi: 10.1007/s12013-007-9000-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wiseman P.W. Image correlation spectroscopy: principles and applications. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2015;2015:336–348. doi: 10.1101/pdb.top086124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scipioni L., Di Bona M., Lanzanò L. Local raster image correlation spectroscopy generates high-resolution intracellular diffusion maps. Commun. Biol. 2018;1:10. doi: 10.1038/s42003-017-0010-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Parslow A.C., Clayton A.H.A., Scott A.M. Confocal microscopy reveals cell surface receptor aggregation through image correlation spectroscopy. J. Vis. Exp. 2018;138:e57164. doi: 10.3791/57164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bragdon B., Thinakaran S., Nohe A. Casein kinase 2 β-subunit is a regulator of bone morphogenetic protein 2 signaling. Biophys. J. 2010;99:897–904. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.04.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rocheleau J.V., Petersen N.O. The Sendai virus membrane fusion mechanism studied using image correlation spectroscopy. Eur. J. Biochem. 2001;268:2924–2930. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shearer L.J., Petersen N.O. Distribution and co-localization of endosome markers in cells. Heliyon. 2019;5:e02375. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hoffmann A.C., Minakaki G., Xiang W. Extracellular aggregated alpha synuclein primarily triggers lysosomal dysfunction in neural cells prevented by trehalose. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:544. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-35811-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Konno M., Hasegawa T., Takeda A. Suppression of dynamin GTPase decreases α-synuclein uptake by neuronal and oligodendroglial cells: a potent therapeutic target for synucleinopathy. Mol. Neurodegener. 2012;7:38. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-7-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Macia E., Ehrlich M., Kirchhausen T. Dynasore, a cell-permeable inhibitor of dynamin. Dev. Cell. 2006;10:839–850. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Reyes J.F., Rey N.L., Angot E. Alpha-synuclein transfers from neurons to oligodendrocytes. Glia. 2014;62:387–398. doi: 10.1002/glia.22611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Oh S.H., Kim H.N., Lee P.H. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit transmission of α-synuclein by modulating clathrin-mediated endocytosis in a parkinsonian model. Cell Rep. 2016;14:835–849. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.12.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Willox A.K., Sahraoui Y.M.E., Royle S.J. Non-specificity of Pitstop 2 in clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Biol. Open. 2014;3:326–331. doi: 10.1242/bio.20147955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Huang M., Wang B., Kang X. α-Synuclein: a multifunctional player in exocytosis, endocytosis, and vesicle recycling. Front. Neurosci. 2019;13:28. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lautenschläger J., Kaminski C.F., Kaminski Schierle G.S. α-Synuclein - regulator of exocytosis, endocytosis, or both? Trends Cell Biol. 2017;27:468–479. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]