Key Points

Question

Was the transition from a paper voucher system to electronic benefits transfer (EBT) cards associated with increased participation in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC)?

Findings

This national economic evaluation compared WIC participation from October 1, 2014, to November 30, 2019, in states that did and did not transition to WIC EBT. In states that implemented EBT cards, WIC participation increased by 7.78% 3 years after implementation, relative to states that continued using paper vouchers.

Meaning

These findings suggest that use of EBT cards for provision of WIC benefits could increase program participation, with beneficial downstream effects on maternal and child health.

This economic evaluation uses data from the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) benefit summary to assess whether a transition from a paper voucher system to electronic benefits transfer cards is associated with greater participation in WIC.

Abstract

Importance

The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) is an important source of nutritional support and education for women and children living in poverty; although WIC participation confers clear health benefits, only 50% of eligible women and children currently receive WIC. In 2010, Congress mandated that states transition WIC benefits by 2020 from paper vouchers to electronic benefits transfer (EBT) cards, which are more convenient to use, are potentially less stigmatizing, and may improve WIC participation.

Objective

To estimate the state-level association between transition from paper vouchers to EBT and subsequent WIC participation.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This economic evaluation of state-level WIC monthly benefit summary administrative data regarding participation between October 1, 2014, and November 30, 2019, compared states that did and did not implement WIC EBT during this time period. Difference-in-differences regression modeling allowed associations to vary by time since policy implementation and included stratified analyses for key subgroups (pregnant and postpartum women, infants younger than 1 year, and children aged 1-4 years). All models included dummy variables denoting state, year, and month as covariates. Data analyses were performed between March 1 and June 15, 2020.

Exposures

Statewide transition from WIC paper vouchers to WIC EBT cards, specified by month and year.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Monthly number of state residents enrolled in WIC.

Results

A total of 36 states implemented WIC EBT before or during the study period. EBT and non-EBT states had similar baseline rates of poverty and food insecurity. Three years after statewide WIC EBT implementation, WIC participation increased by 7.78% (95% CI, 3.58%-12.15%) in exposed states compared with unexposed states. In stratified analyses, WIC participation increased by 7.22% among pregnant and postpartum women (95% CI, 2.54%-12.12%), 4.96% among infants younger than 1 year (95% CI, 0.95%-9.12%), and 9.12% among children aged 1 to 4 years (95% CI, 3.19%-15.39%; P for interaction = .20). Results were robust to adjustment for state unemployment and poverty rates, population, and Medicaid expansion status.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this study, the transition from paper vouchers to WIC EBT was associated with a significant and sustained increase in enrollment. Interventions that simplify the process of redeeming benefits may be critical for addressing low rates of enrollment in WIC and other government benefit programs.

Introduction

In 2018, 1 in 6 children in the US lived in a household experiencing food insecurity.1 Childhood food insecurity has been associated with numerous adverse health outcomes, including increased rates of developmental delay, behavioral problems and school absenteeism, as well as decreased access to preventive care.2,3,4,5 Childhood food insecurity rates have increased since the start of the current COVID-19 pandemic, with more than 40% of mothers with children younger than 12 years recently reporting being food insecure.6

The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) is a federal program that provides nutritional support and education for pregnant and postpartum women and children younger than 5 years who are living in poverty. Participation in WIC is associated with significant health benefits, including decreased incidence of preeclampsia among pregnant women, decreased rates of preterm birth and low birth weight among infants, and decreased food insecurity and improved diet quality among children.7,8,9,10,11 Despite these health benefits, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) estimates that only 50% of eligible women and children in the US currently receive WIC benefits, and WIC participation rates among eligible individuals vary widely across states, from as high as 64.3% to as low as 35.6%.12

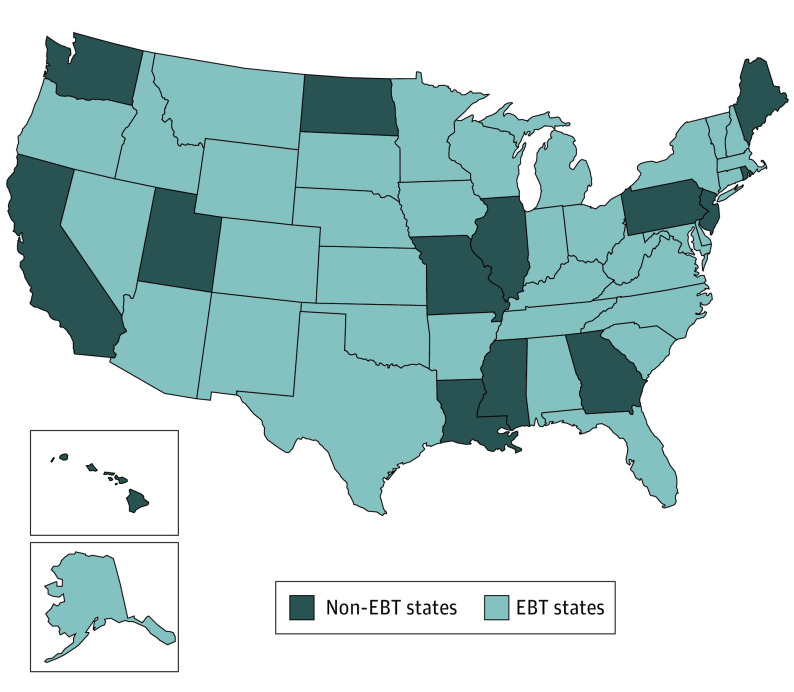

Historically, WIC benefits have been issued in the form of separate paper vouchers, each corresponding to 1 or more covered food items. Qualitative studies suggest that these paper vouchers, which are grouped by food category and must be reviewed and scanned individually by a store cashier at the point of purchase, can serve as a barrier to participation by making the supermarket checkout process logistically challenging and stigmatizing the receipt of WIC benefits.13,14,15 In 2010, Congress passed the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act, which mandated that all states transition WIC benefits from paper vouchers to electronic benefits transfer (EBT) cards by 2020. This mandate was intended to both improve the retail experience for beneficiaries and streamline benefits processing for vendors.16 Between 2010 and 2019, 36 state WIC agencies transitioned to EBT (Figure 1). In states that have implemented WIC EBT, WIC beneficiaries can simply swipe their EBT card at the register, as they would with a debit card, which both increases convenience and reduces stigma associated with WIC use.17 Prior studies have shown that administrative burdens, such as the logistical challenges associated with redeeming paper vouchers, can limit enrollment in and use of other government benefit programs, including Medicaid and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.18,19

Figure 1. Nationwide Geographic Distribution of Electronic Benefits Transfer (EBT) and Non-EBT States.

Thirty-six states implemented the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) EBT either before October 2014 or between October 2014 and November 2019 and were classified as EBT states, whereas 14 states had not yet implemented WIC EBT as of December 2019 and were classified as non-EBT states.

Interventions that reduce such burdens, like WIC EBT, may therefore increase benefit enrollment and use. One recent study found an association between WIC EBT implementation and increased benefit redemption within a single state.17 To our knowledge, no prior studies, however, have examined the association between WIC EBT implementation and program participation across multiple states. In this study, we sought to (1) assess the association between WIC EBT implementation and WIC participation, (2) examine variations in the association of EBT with WIC participation over time, and (3) compare the association of EBT with program participation in analyses stratified by participant age and by states’ baseline participation rate.

Methods

Data Sources

This economic evaluation used state-level data from the USDA WIC Monthly Benefit Summary administrative data sets to assess WIC participation.20 For all 50 states, these data are available from October 1, 2014, through November 30, 2019, and include the number of pregnant and postpartum women, infants younger than 1 year, and children aged 1 to 4 years enrolled in WIC in each month and year. Data from the 2014 American Communities Survey were used to assess states’ baseline demographic characteristics. Annual state-level poverty rates were obtained from the 2014 to 2019 Annual Social and Economic Supplement to the Current Population Survey,21 and monthly state-level unemployment rates were obtained from the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics.22 The institutional review board of the University of Pennsylvania deemed this study to be exempt from review, given the exclusive use of deidentified, publicly available data.

Primary Outcome and Exposure

The primary outcome was monthly WIC participation, measured as the number of WIC beneficiaries in each state, during each month. The primary exposure of interest was WIC EBT implementation. The USDA WIC EBT Detail Status Report, which provides actual and projected statewide WIC EBT implementation dates for all 50 states, was used to determine the month and year when each state completed statewide implementation of WIC EBT.23

Statistical Analysis

State-level baseline socioeconomic and demographic characteristics, including poverty rate, unemployment rate, food insecurity rate, and proportion of White, Black, and Hispanic residents, were compared across states implementing EBT during or before the study period (EBT states) and those that continued to use paper vouchers during this period (non-EBT states).

A difference-in-differences analytic approach with policy-by-time interaction (also known in the economics literature as an event study specification) was chosen in order to allow associations between EBT implementation and WIC participation to vary over time, as more program administrators and potential beneficiaries became aware of the transition and more existing beneficiaries experienced the improved convenience and reduced stigma of WIC EBT.

Multivariable generalized linear models using a negative binomial distribution were developed in which the independent variables of interest were a series of binary indicators noting whether a state had transitioned to WIC EBT each month (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). States that had not yet implemented WIC EBT were assigned zeros for each of these indicator terms. This approach allowed for comparison of changes in WIC participation in each month before and after WIC EBT implementation in intervention states with secular trends in control states. Given the small number of data points, we estimated single coefficients for time points 39 or more months before implementation and 39 or more months after implementation.24 All regression models used a log link, with state population specified as an exposure. Estimates were reported as percentage changes. Difference-in-differences estimates were used to estimate the number of additional WIC beneficiaries across all 36 intervention states attributable to the change from paper vouchers to WIC EBT.

All regression models included state, month, and year dummy variables as covariates to adjust for potential confounding from state-level time invariant characteristics, seasonality in WIC participation, and national secular trends. State-level trends in WIC eligibility from 2014 to 2017 were examined and found to be stable (eFigure 2 in the Supplement), indicating that state-level differences in WIC eligibility would be expected to be absorbed by the state dummy variables included in our model.

All SEs and 95% CIs were adjusted for clustering by state through a robust variance estimator. All observations were weighted by 2014 state population. Analyses were conducted using Stata software, version 15.1 (StataCorp LLC). All P values were from 2-sided tests, and results were deemed statistically significant at P < .05. Data analyses were performed between March 1 and June 15, 2020.

Additional Analyses

Given well-known declines in WIC participation by child age,12 stratified analyses examined associations between WIC EBT and program participation across 3 age groupings: pregnant and postpartum women, infants younger than 1 year, and children aged 1 to 4 years. A separate stratified analysis was specified to examine the association of WIC EBT with participation based on states’ baseline WIC participation rates, by calculating the mean state-level participation rate in 2014 and examining associations in states that were above and below this average.

Additional sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the robustness of the findings. These included (1) annual poverty rate and monthly unemployment rate as covariates, (2) Medicaid expansion status and adoption of an online enrollment assistance platform as covariates (eFigure 3 in the Supplement), and (3) using a linear regression model, because these models are known to have unbiased estimation properties in fixed effects analysis.25 The primary outcome in this model was the natural log transformed proportion of state residents enrolled in WIC each month.

Results

Study Sample

Thirty-six states had implemented WIC EBT by November 2019, the end of our study period, whereas 14 states had not yet implemented WIC EBT at that time (Figure 1). State baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. EBT and non-EBT states had similar rates of overall poverty, child poverty, and food insecurity. Non-EBT states differed from EBT states in that they had a higher mean (SD) unemployment rate (6.78% [0.9%] vs 5.86 [0.9%]), a higher median household income ($65 185 [IQR, $9181] vs $59 286 [IQR, $8660]), and a greater mean (SD) proportion of residents who identified as Hispanic (20.5% [14.7%] vs 15.7% [12.4%]).

Table 1. Characteristics of EBT States and Non-EBT Statesa.

| Baseline characteristic | States value, mean (SD), % | |

|---|---|---|

| EBT (n = 36) | Non-EBT (n = 14) | |

| Baseline WIC participation rate | 52.4 (5.4) | 57.7 (10.4) |

| State residents living in poverty | 14.9 (3.1) | 14.5 (3.2) |

| Children living in poverty | 21.6 (4.3) | 21.4 (4.0) |

| Unemployment rate | 5.86 (0.9) | 6.78 (0.9) |

| Median household income, $ | 59 286 (8660) | 65 185 (9181) |

| Food insecurity rate | 15.8 (2.9) | 14.6 (2.8) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 65.0 (14.0) | 56.2 (17.1) |

| Black | 12.2 (6.8) | 11.6 (10.2) |

| Hispanic | 15.7 (12.4) | 20.5 (14.7) |

Abbreviations: EBT, electronic benefits transfer; WIC, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

All values represent the average (mean) values and associated SDs across all included states in each category, weighted by 2014 state population.

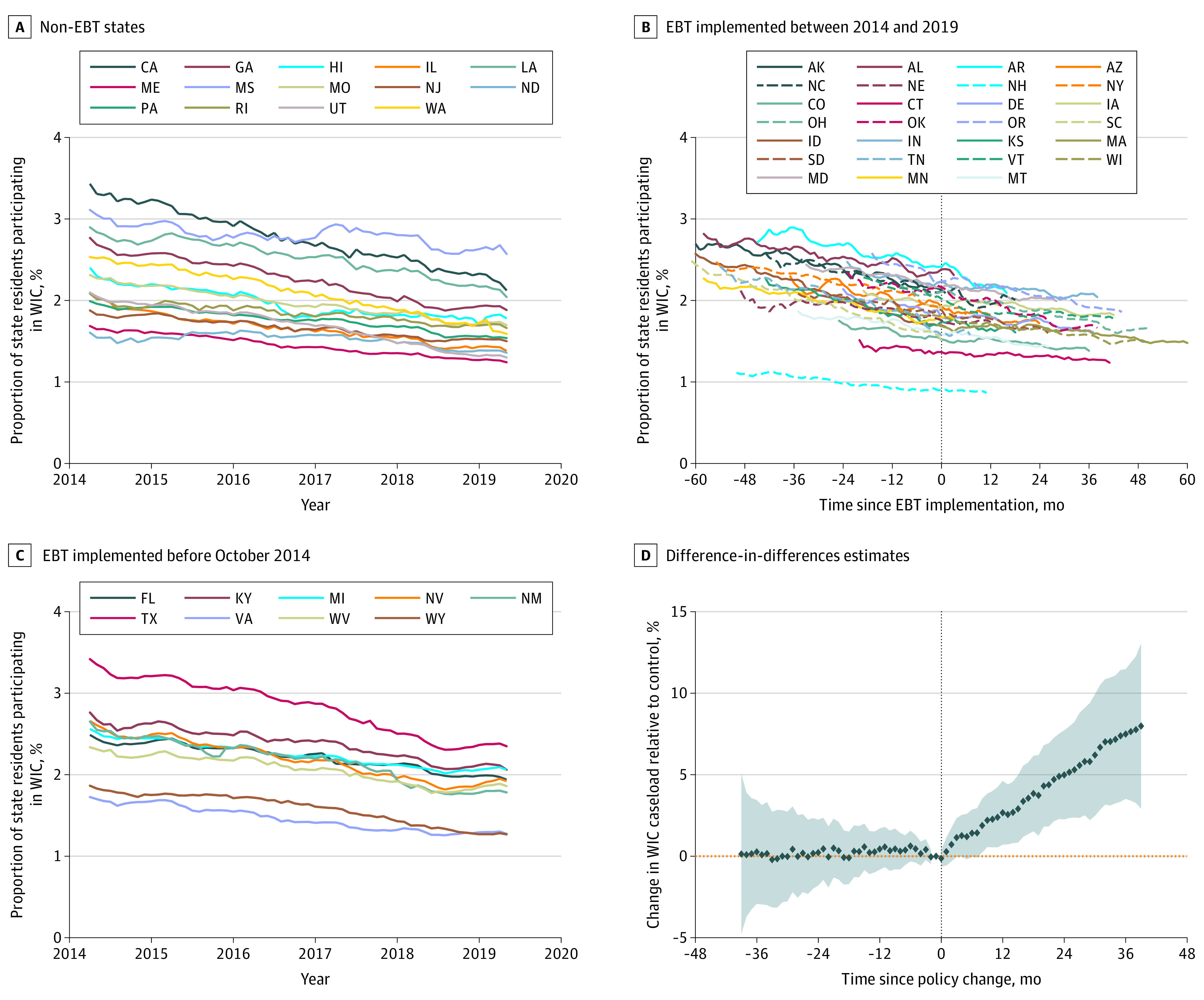

Association Between WIC EBT and WIC Program Participation

Trends in WIC program participation over time are shown in Figure 2A-C. Figure 2A shows trends over time in the 14 non-EBT states, Figure 2B shows trends before and after EBT implementation in the 27 states that implemented WIC EBT during our study period, and Figure 2C shows trends over time in the 9 states that implemented WIC EBT before October 2014. Main estimates of changes in WIC program participation over time are shown in Figure 2D. Each point in the figure reflects the percentage difference in WIC participation in intervention states as compared with control states in the months before and after the transition from paper vouchers to WIC EBT. Participation in EBT and non-EBT states followed roughly similar trends before this transition, with no statistically significant differences, as noted by the shaded region representing the 95% CI spanning 0% throughout the preimplementation period. After EBT implementation, WIC participation in EBT vs non-EBT states increased sharply relative to prior trends. Within 6 months of WIC EBT implementation, statistically significant differences in participation between intervention and control states emerged and continued to enlarge. Three years after implementing EBT, WIC participation increased by 7.78% (95% CI, 3.58%-12.15%) in intervention states compared with control states (Table 2). This increase corresponds to more than 220 000 additional WIC beneficiaries over the study period.

Figure 2. Trends in Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) Participation Over Time and Difference-in-Differences Estimates of the Association Between WIC Electronic Benefits Transfer (EBT) Implementation and WIC Participation in All 50 States.

A, Trends in WIC participation over time in non-EBT states. B, Trends in WIC participation over time in states that implemented EBT between 2014 and 2019, by time from policy implementation. C, Trends in WIC participation over time in states that implemented EBT before October 2014. D, Difference-in-differences estimates (difference in WIC caseload between EBT and non-EBT states, in the months before and after this policy change). In panel D, the x-axis represents the number of months relative to statewide WIC EBT implementation, with event months 39 or more months before or after EBT implementation combined into a single time point. Shaded areas represent 95% CIs.

Table 2. Nationwide Difference-in-Differences Estimates for EBT and Non-EBT Statesa.

| Regression model | Change in WIC enrollment 3 y after EBT implementation in EBT states relative to non-EBT states, % (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Primary analysis | ||

| All WIC beneficiaries | 7.78 (3.58 to 12.15) | <.001 |

| Analyses stratified by participant group | ||

| Pregnant and postpartum women | 7.22 (2.54 to 12.12) | .002 |

| Infants (<1 y) | 4.96 (0.95 to 9.12) | .02 |

| Children (1-4 y) | 9.12 (3.19 to 15.39) | .002 |

| Analyses stratified by states’ baseline participation rate | ||

| Low | 14.88 (4.11 to 26.76) | .006 |

| High | 4.76 (−1.84 to 11.82) | .16 |

Abbreviations: EBT, electronic benefits transfer; WIC, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

Difference-in-differences estimates are presented as percentage point changes. The 95% CIs are corrected for clustering at the state level. All estimates include state, month, and year dummy variables as covariates.

Additional Analyses

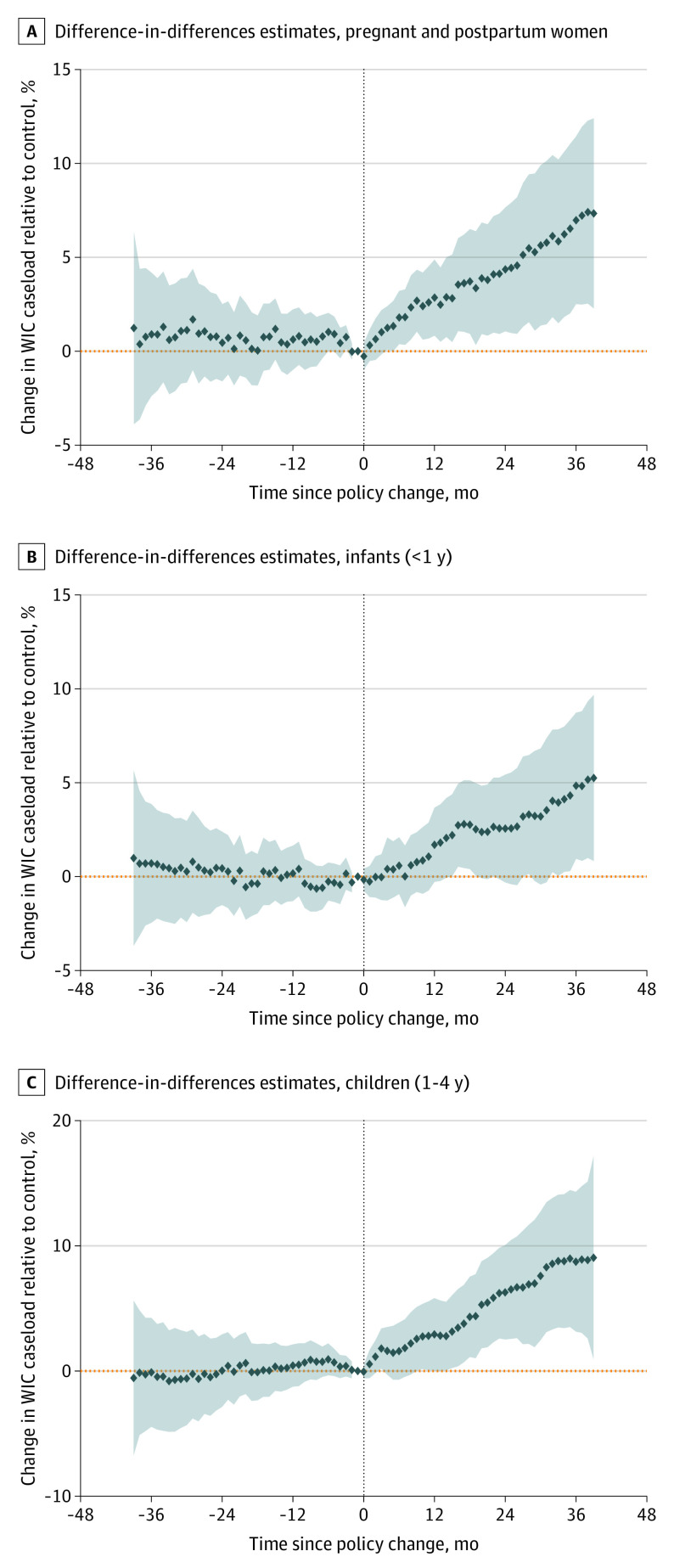

Similar results were found for analyses stratified by age group (Figure 3), with an increase in WIC participation at 3 years observed among infants (4.96%; 95% CI, 0.95%-9.12%), pregnant and postpartum women (7.22%; 95% CI 2.54%-12.12%), and children aged 1 to 4 years (9.12%; 95% CI, 3.19%-15.39%). Estimated associations across these groups were not statistically different (P = .20 for the interaction term). Comparing the association of WIC EBT with participation in states with baseline participation rates above and below the national average (eFigure 4 in the Supplement), states with low baseline participation rates experienced a significant increase in WIC participation as a result of implementing EBT (14.88%; 95% CI, 4.11%-26.76%). States with high baseline participation rates also experienced a relative increase in participation (4.76%; 95% CI, −1.84% to 11.82%), although this pattern may simply have been a continuation of preexisting trends.

Figure 3. Nationwide Difference-in-Differences Estimates of the Association Between the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) Electronic Benefits Transfer (EBT) Implementation and WIC Participation Stratified by Age Group.

Stratified difference-in-differences estimates (adjusted difference in WIC caseload between exposed and unexposed states) are plotted across age groups (pregnant and postpartum women in panel A, infants <1 y of age in panel B, and children aged 1-4 y in panel C). The x-axis represents the number of months relative to statewide WIC EBT implementation, with event months 39 or more months before or after EBT implementation combined into a single time point. Shaded areas represent 95% CIs.

The substantive analytic findings remained unchanged when adjusting for unemployment rate and poverty rate and when accounting for Medicaid expansion and WIC online enrollment assistance as concurrent interventions (eTable in the Supplement). In sensitivity analysis examining concurrent interventions, after adjusting for WIC EBT, states that expanded Medicaid had a 1.82% relative increase in WIC participation (95% CI, 0.33%-3.34%), and states that implemented WIC online enrollment assistance had no significant change in WIC participation (1.67%; 95% CI, −1.02% to 4.43%). In a sensitivity analysis using a linear regression model, EBT was associated with a 8.89% increase in WIC participation proportion at 3 years (95% CI, 3.31%-14.77%).

Discussion

In this policy-focused economic evaluation of national scope, we found that EBT, an intervention aimed at improving the accessibility and ease of use of WIC benefits, was associated with increased program participation. States that implemented WIC EBT experienced an increase in program participation that began within 6 months of statewide implementation and continued for more than 3 years. Altogether, our estimates suggest that the transition to EBT was associated with over 220 000 additional WIC beneficiaries over the study period, relative to what would have been expected had EBT not been adopted.

These findings suggest that interventions focused on reducing the inconvenience and stigma associated with government benefit programs can lead to meaningful increases in program participation. Our results are bolstered by prior qualitative studies in which WIC beneficiaries described the inconvenience and stigma associated with using paper vouchers at the point of purchase and cited these factors as barriers to participation.13,14,15 We found that when states implemented EBT, an intervention aimed at overcoming these barriers, they experienced associated increases in program enrollment that were both substantial and sustained. Although these increases may generate increased program expenditures for states in the short term, due to the greater number of beneficiaries, they are likely to pay dividends in the long term, given the associations between WIC participation and improved maternal, infant, and child health outcomes, including decreased rates of preterm birth, infant mortality, and childhood food insecurity.7,8,9,10,11

In analyses stratified by age group, children aged 1 to 4 years experienced a larger relative increase in WIC participation after EBT implementation. This outcome is noteworthy given the documented decline in WIC participation after age 1 year and the crucial role that WIC plays in ensuring adequate nutrition for children aged 1 to 4 years, who are not yet old enough to receive school-based meals.9,10,12 In 1 qualitative study examining mothers’ reasons for leaving the WIC program after their children turned 1 year of age, more than 25% reported feeling that WIC benefits were not worth the time and effort required to receive them.26 Our results suggest that EBT may mitigate this perception and thereby increase WIC participation among this particularly vulnerable population. Given the time lag between EBT implementation and increased participation in this age group, these findings also underscore the importance of targeted outreach to parents of children aged 1 to 4 years to ensure that they are made aware of programmatic improvements intended to simplify the enrollment and redemption process. In analyses stratified by states’ baseline participation rate, there was a greater increase in WIC participation after EBT implementation in states with low baseline participation rates, suggesting that these states may have the most to gain by streamlining benefits enrollment.

In a sensitivity analysis examining other concurrent interventions, there was a positive association between Medicaid expansion and WIC participation. This finding is in line with previous studies showing that interventions aimed at increasing participation in individual government benefit programs may have beneficial spillover effects on participation in other benefit programs.27 No significant association between WIC online enrollment assistance platforms and WIC participation was detected, suggesting that this intervention aimed at streamlining the appointment scheduling process may not be sufficient to increase participation.

This study has particular relevance in the context of the current COVID-19 pandemic and economic recession. Despite the increases in WIC participation associated with EBT implementation, the USDA estimates that before the pandemic, more than 6.8 million WIC-eligible women and children were not receiving these benefits.12 With food insecurity and unemployment rates now at record highs, an even greater number of families will likely need to rely on WIC, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, and other government benefit programs. Our findings underscore the importance of states implementing interventions focused on making these programs more convenient and less stigmatizing for beneficiaries. This effort could involve both expanding existing initiatives, such as WIC EBT and online enrollment assistance, and implementing new programs, such as Pandemic EBT, which allows qualifying families to receive EBT cards equivalent to the cash value of their children’s school-based meals rather than traveling to meal pick-up sites in person.28,29,30

The USDA has also instituted several new regulations that allow states to change how they deliver benefits during the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, by allowing state WIC agencies to issue up to 4 months of benefits on EBT cards at once and by waiving the requirement that families present to WIC offices in person to pick up their WIC EBT cards.31 WIC recipients may benefit if states both sustain and build on these innovations after pandemic-related restrictions are lifted. For example, state WIC offices could continue to waive the in-person appointment requirement and instead offer phone or video visits as a way to improve access for families with barriers to transportation, and states could provide financial incentives for small businesses who choose to accept WIC in order to reduce vendor drop-out associated with EBT adoption and to ensure beneficiaries are able to continue to redeem benefits at stores in their communities.32 As these innovations are implemented, rigorous evaluation of their effects on both participation and downstream health outcomes, with particular attention to disparities that could unintentionally be created through the use of technology to facilitate benefits enrollment and use, will be crucial.

Limitations

This study has 3 main limitations. First, although our results were robust to several sensitivity analyses, the observational research design does not allow a causal interpretation of the findings. There may be time-varying, state-level characteristics not included in our models that coincided with the implementation of WIC EBT and were also associated with WIC participation. Second, because our primary outcome was WIC participation, we cannot directly draw definitive conclusions about the downstream effects of WIC EBT on maternal or child health, although we can infer that these effects are likely, given the existing literature on the health effects of WIC participation. Third, because our data set did not include individual or state-level information about the race/ethnicity or location of WIC participants, we were unable to examine the differential effects of WIC EBT on participation among subgroups of beneficiaries, such as racial and ethnic minority groups and beneficiaries residing in rural areas. Future studies should specifically examine the effect of WIC EBT on participation and health outcomes among these subgroups to determine which groups may have benefited most and least from the WIC EBT transition. Future research should also look at state-level differences in program participation based on individual states’ strategies for implementing EBT, as these differences could help guide the successful implementation of future innovations aimed at improving benefit delivery.

Conclusions

In this national, state-level economic evaluation, statewide implementation of WIC EBT was associated with a significant and sustained increase in WIC program participation. These findings suggest that interventions that simplify the process of redeeming government benefits may be critical for addressing low rates of enrollment in WIC and other government benefit programs.

eFigure 1. Regression Model

eFigure 2. State-Level Trends in WIC Eligibility, 2014-2017

eFigure 3. States Implementing WIC Online Enrollment Assistance and State Medicaid Expansion Status, 2014-2019

eFigure 4. Difference-in-Differences Estimates of the Association Between WIC EBT Implementation and WIC Participation Stratified by Baseline Participation Rate

eTable. Nationwide Difference-in-Differences Estimates for EBT and Non-EBT States: Sensitivity Analyses

References

- 1.Coleman-Jensen A, Gregory C, Singh A. Household food security in the United States in 2018. USDA Econ Res Serv. 2019;(September):1-47. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2504067 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rose-Jacobs R, Black MM, Casey PH, et al. Household food insecurity: associations with at-risk infant and toddler development. Pediatrics. 2008;121(1):65-72. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alaimo K, Olson CM, Frongillo EA Jr. Food insufficiency and American school-aged children’s cognitive, academic, and psychosocial development. Pediatrics. 2001;108(1):44-53. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11433053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peltz A, Garg A. Food insecurity and health care use. Pediatrics. 2019;144(4):e20190347. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drennen CR, Coleman SM, Ettinger de Cuba S, et al. Food insecurity, health, and development in children under age four years. Pediatrics. 2019;144(4):e20190824. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.NORC at the University of Chicago for the Data Foundation . The COVID-19 household impact survey: week 1. Accessed June 1, 2020. https://www.covid-impact.org

- 7.Hamad R, Collin DF, Baer RJ, Jelliffe-Pawlowski LL. Association of revised WIC food package with perinatal and birth outcomes: a quasi-experimental study. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(9):845-852. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.1706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kreider B, Pepper JV, Roy M. Identifying the effects of WIC on food insecurity among infants and children. South Econ J. 2016;82(4):1106-1122. doi: 10.1002/soej.12078 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tester JM, Leung CW, Crawford PB. Revised WIC food package and children’s diet quality. Pediatrics. 2016;137(5):e20153557. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schanzenbach DW, Thorn B. Food support programs and their impacts on young children. Accessed May 15, 2020. https://www.healthaffairs.org/briefs

- 11.Soneji S, Beltrán-Sánchez H. Association of Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children with preterm birth and infant mortality. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(12):e1916722. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.16722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.US Department of Agriculture. WIC 2017. eligibility and coverage rates. Accessed May 18, 2020. https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic-2017-eligibility-and-coverage-rates

- 13.Chauvenet C, De Marco M, Barnes C, Ammerman AS. WIC recipients in the retail environment: a qualitative study assessing customer experience and satisfaction. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2019;119(3):416-424.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2018.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bertmann FMW, Barroso C, Ohri-Vachaspati P, Hampl JS, Sell K, Wharton CM. Women, Infants, and Children cash value voucher (CVV) use in Arizona: a qualitative exploration of barriers and strategies related to fruit and vegetable purchases. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2014;46(3)(suppl):S53-S58. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2014.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weber SJ, Wichelecki J, Chavez N, Bess S, Reese L, Odoms-Young A. Understanding the factors influencing low-income caregivers’ perceived value of a federal nutrition programme, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC). Public Health Nutr. 2019;22(6):1056-1065. doi: 10.1017/S1368980018003336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Congress.gov. Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010. Accessed October 17, 2020. https://www.congress.gov/congressional-report/111th-congress/senate-report/178

- 17.Hanks AS, Gunther C, Lillard D, Scharff RL. From paper to plastic: understanding the impact of eWIC on WIC recipient behavior. Food Policy. 2019;83:83-91. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2018.12.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moynihan DP, Herd P, Ribgy E. Policymaking by other means: do states use administrative barriers to limit access to Medicaid? Adm Soc. 2016;48(4):497-524. doi: 10.1177/0095399713503540 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herd P, Moynihan DP. Administrative Burden: Policymaking by Other Means. Russell Sage; 2018.

- 20.US Department of Agriculture. WIC data tables. Accessed May 18, 2020. https://www.fns.usda.gov/pd/wic-program

- 21.Flood S, King M, Ruggles S, Warren JR. Integrated Public Use Microdata Series. University of Minnesota; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 22.US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Local area unemployment statistics . Accessed May 18, 2020. https://www.bls.gov/lau/

- 23.US Department of Agriculture. WIC EBT activities. Accessed May 18, 2020. https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/wic-ebt-activities

- 24.Goodman-Bacon A. Difference-in-Differences With Variation in Treatment Timing. National Bureau of Economic Research Inc; 2018. doi: 10.3386/w25018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greene W. The behaviour of the maximum likelihood estimator of limited dependent variable models in the presence of fixed effects. Econom J. 2004;7(1):98-119. doi: 10.1111/j.1368-423X.2004.00123.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacknowitz A, Tiehen L. Transitions into and out of the WIC Program: a cause for concern? Soc Serv Rev. 2009;83(2):151-183. doi: 10.1086/600111 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lanese BG, Fischbein R, Furda C. Public program enrollment following us state Medicaid expansion and outreach. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(10):1349-1351. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rummo PE, Bragg MA, Yi SS. Supporting equitable food access during national emergencies—the promise of online grocery shopping and food delivery services. JAMA Heal Forum. Published online March 27, 2020. doi: 10.1001/JAMAHEALTHFORUM.2020.0365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.US Department of Agriculture. FNS launches the online purchasing pilot. Accessed May 20, 2020. https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/online-purchasing-pilot

- 30.Ahmed A. Here’s how states can deliver more food assistance to low-income children during the COVID-19 pandemic. Accessed May 20, 2020. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200508.322805/full/

- 31.US Department of Agriculture. FNS Response to COVID-19. Accessed May 19, 2020. https://www.fns.usda.gov/disaster/pandemic/covid-19

- 32.Meckel BK. Is the cure worse than the disease? unintended effects of payment reform in a quantity-based transfer program. Am Econ Rev. 2020;110(6):1821-1865. doi: 10.1257/aer.20160164 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Regression Model

eFigure 2. State-Level Trends in WIC Eligibility, 2014-2017

eFigure 3. States Implementing WIC Online Enrollment Assistance and State Medicaid Expansion Status, 2014-2019

eFigure 4. Difference-in-Differences Estimates of the Association Between WIC EBT Implementation and WIC Participation Stratified by Baseline Participation Rate

eTable. Nationwide Difference-in-Differences Estimates for EBT and Non-EBT States: Sensitivity Analyses