Abstract

This cohort study assessed the frequency of approvals of first generic drugs with skinny labels in the US.

Brand-name drug manufacturers in the US use several strategies to delay generic competition,1 including obtaining a thicket of patents to protect beyond a drug’s active ingredient and original use.2 Such patents can cover use of the drug for supplemental indications that the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approves after a medication is already on the market.

To prevent these secondary method-of-use patents from delaying generic competition, the FDA approves generic formulations with product labels that omit the indications for which the brand-name drug still has patent protection.3 These formulations are known as “skinny-label” generic drugs, a reference to the carving out of patented or other protected uses for which the brand-name drug is approved.

Skinny labeling can promote more timely availability of generic drugs and prevent delays in low-cost competition for brand-name products. In this study, we assessed the frequency of approvals of first generic drugs with skinny labels in the US.

Methods

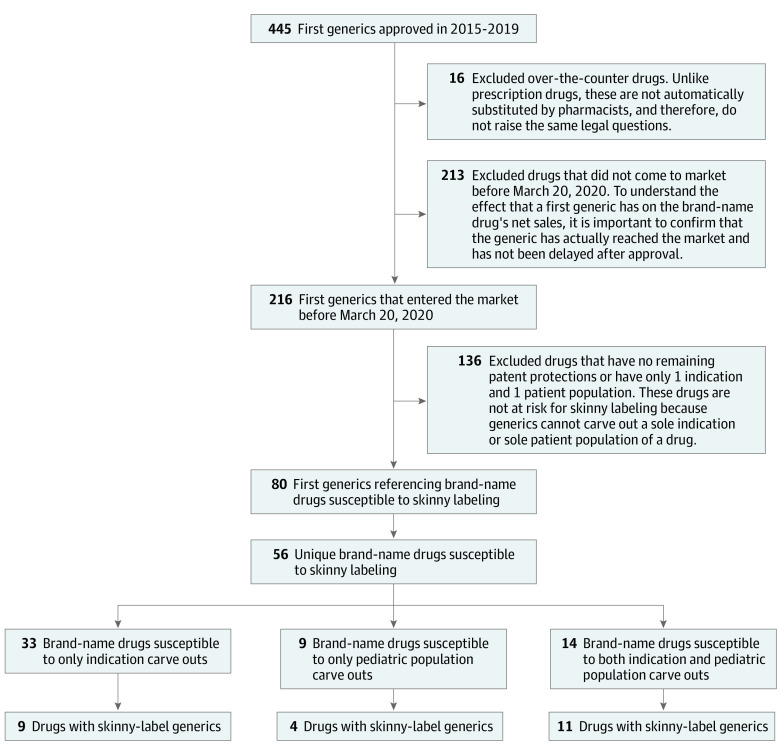

In this cohort study, we identified all first generic drug approvals in the US from 2015 through 2019. We excluded over-the-counter drugs and, because not all generic drugs enter the market immediately after approval,4 drugs with no generic dispensing record in Optum's deidentified Clinformatics Data Mart database before March 31, 2020 (Figure). We collected data on drug characteristics, historical labeling, and patent and exclusivity information from public FDA sources as well as brand-name drug revenue information from SSR Health (http://www.ssrhealth.com/). The Mass General Brigham Institutional Review Board approved the study and waived patient consent because we used only deidentified commercial claims data.

Figure. Identification of Brand-Name Drugs Susceptible to “Skinny Labeling,” 2015-2019.

Exclusion of drugs that had not entered the market was determined by using the corresponding National Drug Code numbers to search for a prescription claim prior to March 20, 2020, in Optum's deidentified Clinformatics Data Mart database.

We identified each brand-name drug (defined by its New Drug Application number) referenced by 1 or more of the first generics. The brand-name drugs most susceptible to skinny labeling were those with outstanding patents or exclusivities at the time of generic approval and more than 1 approved indication or patient population (eg, pediatric populations). We grouped the susceptible brand-name drugs into 3 carve-out categories: indication carve outs, pediatric population carve outs, or both indication and pediatric population carve outs. We then determined whether all first-approved generic drugs for each brand-name drug had skinny labels by reviewing their FDA approval documents or by identifying differences between the generic and brand-name labels.

Results

We identified a total of 56 brand-name drugs first available as generics from 2015 to 2019 that were susceptible to skinny labeling, 24 (43%) of which had generic formulations with skinny labels. The median time between skinny-label generic approval and the expiration date of the patent or exclusivity protecting the carved-out indications was 3.2 years (interquartile range [IQR], 1.8-5.7 years).

The most common information carved out of the brand-name label was related to indications protected by method-of-use patents (n = 9; 38%) or by nonpatent FDA-granted exclusivities, including Orphan Drug Act–designated indications (n = 8; 33%) and new patient population investigations (n = 6; 25%) such as studying the drug in a pediatric population. The median net sales in the year preceding a first generic drug’s approval was $522 million (IQR, $102-$748 million) for brand-name drugs with full-label generic drugs and $852 million (IQR, $329-$2480 million) for brand-name drugs with skinny-label generic drugs (Table).

Table. Characteristics of Brand-Name Drugs With Full-Label and “Skinny-Label” First Generic Approvals, 2015-2019.

| Drug characteristic | Brand-name drugs, No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Susceptible to skinny labeling | With full-label generic drug | With skinny-label generic drug | |

| Total No. of brand-name drugs | 56 | 32 | 24 |

| Year of first generic approval | |||

| 2015 | 19 (34) | 14 (44) | 5 (21) |

| 2016 | 10 (18) | 6 (19) | 4 (17) |

| 2017 | 12 (21) | 9 (28) | 3 (13) |

| 2018 | 7 (13) | 2 (6) | 5 (21) |

| 2019 | 8 (14) | 1 (3) | 7 (29) |

| Brand-name label includes: | |||

| Pediatric population | 23 (41) | 8 (25) | 15 (63) |

| Supplemental indicationa | 34 (61) | 14 (44) | 20 (83) |

| >2 Indications/populations | 28 (50) | 14 (44) | 14 (58) |

| Net salesb in 1 y prior to first generic approval, in millions, US $ | |||

| <500 | 19 (34) | 10 (31) | 9 (38) |

| 500-2000 | 15 (27) | 10 (31) | 5 (21) |

| >2000 | 5 (9) | 0 | 5 (21) |

| Not available | 17 (30) | 12 (38) | 5 (21) |

Supplemental indication is a new use approved by the US Food and Drug Administration that was not included in the original brand-name drug approval.

Calculated by summing net sales for the 4 quarters before brand-name drug approval, using data from SSR Health. Two brand-name drugs in the cohort were referenced by both skinny-label and full-label generic drugs, and we categorized these as full labels only.

Discussion

We found that in the US, skinny labeling is frequent among brand-name drugs facing new generic competition. Skinny labeling facilitates timely entry of generic drugs, particularly for high-revenue brand-name drugs. Without skinny labeling, our findings suggest that generic drug entry for susceptible brand-name drugs could be delayed by multiple years. A limitation of the study is that our strict criteria for determining susceptibility to skinny labeling may have underestimated the delay.

Despite the practice of skinny labeling being explicitly permitted by statute, recent court decisions have increased the financial risk of generic manufacturers considering using a skinny label by subjecting them to claims for inducement of patent infringement.5 Subjecting generic manufacturers to heightened risk of legal damages for their skinny labels could reduce incentives to use this pathway and lead to delays in generic competition that lowers prices for patients and the health care system.

The US Congress and the FDA could consider actions to ensure that skinny labeling remains an attractive pathway for generic manufacturers. Skinny labels prevent brand-name drug manufacturers from delaying competition by obtaining patents covering subsequent FDA-approved indications of their drugs.

References

- 1.Vokinger KN, Kesselheim AS, Avorn J, Sarpatwari A. Strategies that delay market entry of generic drugs. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(11):1665-1669. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.4650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richards KT, Ward EH, Hickey KJ. Drug pricing and pharmaceutical patenting practices. Congressional Research Service. February 11, 2020. Accessed February 8, 2021. https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20200211_R46221_145095cd7a7d37a957722140d6e708a1d52de5a1.pdf

- 3.US Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, 21 USC §355 (2018). Accessed February 8, 2021. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2010-title21/pdf/USCODE-2010-title21-chap9-subchapV-partA-sec355.pdf

- 4.Rome BN, Lee CC, Kesselheim AS. Market exclusivity length for drugs with new generic or biosimilar competition, 2012-2018. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2021;109(2):367-371. doi: 10.1002/cpt.1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bloomfield D. Speech, drugs, and patent inducement. February 4, 2021. Accessed February 15, 2021. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3744403