Abstract

The advent of facile genome engineering technologies has made the generation of knock-in gene-expression or fusion-protein reporters more tractable. Fluorescent protein labeling of specific genes combined with surface marker profiling can more specifically identify a cell population. However, the question of which fluorescent proteins to utilize to generate reporter constructs is made difficult by the number of candidate proteins and the lack of updated experimental data on newer fluorescent proteins. Compounding this problem, most fluorescent proteins are designed and tested for use in microscopy. To address this, we cloned and characterized the detection sensitivity, spectral overlap and spillover spreading of 13 monomeric fluorescent proteins to determine utility in multicolor panels. We identified a group of five fluorescent proteins with high signal to noise ratio, minimal spectral overlap and low spillover spreading making them compatible for multicolor experiments. Specifically, generating reporters with combinations of three of these proteins would allow efficient measurements even at low-level expression. Because the proteins are monomeric, they could function either as gene-expression or as fusion-protein reporters. Additionally, this approach can be generalized as new fluorescent proteins are developed to determine their usefulness in multicolor panels.

Keywords: Fluorescent Proteins, Genetic Reporters, Compensation, Mice

Introduction

From the first successful use of Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) as a marker for imaging in 1994, fluorescent proteins have revolutionized research. Stemming from the development of GFP [1–3], a large number of fluorescent proteins have been discovered and generated, with origins outside GFP’s Aequorea victoria [4–9]. Most natural fluorescent proteins cloned from different organisms function as dimers or tetramers, which can lead to aggregation of protein in the cell [10]. Protein aggregates can cause cytotoxicity, limiting the biological applications of those fluorescent proteins. The development of monomeric proteins helped mitigate problems stemming from protein dimerization [11, 12] and more accurately functioned as protein-level reporters for genetically-encoded fluorescent tags [13] allowing for diversification of their applications.

Knock-in gene-expression or fusion-protein reporters can greatly improve the identification of cell populations where conventional surface marker profiling fails. The development of more sophisticated fluorescent proteins with a wide range of excitation and emission spectra have facilitated increasingly complex flow cytometry assays [14]. However, existing data on flow cytometry tested fluorescent proteins is quickly becoming outdated, as new fluorescent proteins are developed almost every year, with at least 28 new proteins developed in the last five years [15–41]. Review articles cover reported fluorescent protein characteristics for flow cytometry and microscopy, but comprehensive individual and combinatorial experimental testing in a cytometer is minimal[10, 42–44]. All of these factors make choosing a multicolor panel useful for knock-in gene-expression or fusion-protein reporters difficult, because the optimal combination of fluorescent proteins is unclear.

In order to address the need for concise data on the flow cytometric properties of fluorescent proteins that can be used for knock-in gene-expression or fusion-protein reporters, we selected a panel of 13 monomeric fluorescent proteins to examine: Venus [45], monomeric Infrared Fluorescent Protein (mIFP) [41], Long Stokes Shift monomeric Orange (LssmOrange) [46], Tag Red Fluorescent Protein 657 (TagRFP657) [47], monomeric Orange2 (mOrange2) [48], monomeric Apple(mApple) [48], Sapphire [49], monomeric Tag Blue Fluorescent Protein (mTagBFP2) [50], tdTomato [11], monomeric Cherry (mCherry) [11], Enhanced Yellow Fluorescent Protein (EYFP) [51], monomeric Cerulean3 (mCerulean3) [52], and Enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein (EGFP) [53]. These proteins were chosen because they can be excited with common laser lines used in flow cytometry and have low concatemerization. Monomeric fluorescent proteins induce lower cytotoxicity, so these fluorescent proteins can be used for biological assays. Moreover, their monomeric nature also allows them to function as fusion proteins. Comparable assessments of combinations of fluorescent proteins exist for microscopy, underscoring the need for similar experiments in the context of flow cytometry [54]. Notably, we chose to include EGFP in the panel because of its widespread use and status as a gold standard fluorescent protein [10]. Similarly, EYFP was also included because it is a legacy reagent.

Researchers often face a dilemma in creating a new reporter mouse; which fluorescent protein to use. There are multiple criteria to determine efficacy of fluorescent molecules in a multicolor panel and include brightness, degree of fluorescence spillover and spreading error. In this study, the performance of each fluorescent protein was characterized by examining these factors. We demonstrate the utility of five fluorescent proteins with optimal characteristics for multicolor experiments, three of which can be easily used simultaneously (GFP or Venus, mTagBFP2 and either mIFP or TagRFP657). They can be individually detected even at low levels and present little spectral overlap when used together. Additionally, this approach can be generalized to test new fluorescent proteins as they are developed.

Materials and Methods

Fluorescent Proteins

Protein sequences for each of the following fluorescent proteins were obtained from their respective publications, and DNA sequences were synthesized with optimized codon usage for murine and human cells (gBLOCKs; Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, Iowa): Venus, mIFP, LssmOrange, TagRFP657, mOrange2, mApple, Sapphire, mTagBFP2 and mCerulean3. Notably, while the encoded proteins are the same as the published protein sequence, the DNA sequence encoding them is different than the published sequence. Overhangs were designed to flank the fluorescent proteins, 43 bp on the 5’ end and 37 bp on the 3’ end, in order to insert the sequences into the MSCV Puro using the NEBuilder HiFi DNA Assembly Kit (New England Biolabs Ipswich, MA). All MSCVpuro constructs have been submitted to AddGene (AG; Cambridge, MA) and are available for distribution [Venus (AG #96940), mIFP (AG #96951), LssmOrange (AG #96937), TagRFP657 (AG #96939), mOrange2 (AG #96938), mApple (AG #96934), Sapphire (AG #96950), mTagBFP2 (AG #96935), tdTomato (AG #97079), and mCerulean3 (AG #96936)]. NEB 5-alpha Competent E. coli were transformed, and DNA was prepped (Qiagen Hilden, Germany) and sequence verified. EYFP (pMSCV-IRES-YFP II) was a generous gift from Mohammed Azam (CCHMC). EGFP (MIGR1; AddGene #27490), tdTomato-N1 (Addgene #54642) and pMSCV-mCherry (AddGene #52114) were obtained from AddGene.

Cell Culture

Mouse Kidney Epithelial 4 (mK4) cells were a kind gift from S. Steven Potter (CCHMC). mK4 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with penicillin, streptomycin, L-glutamine, and 10% FBS. Sub-confluent cultures were maintained. 293T (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) cells were maintained in Opti-MEM supplemented with L-glutamine and 10% FBS. Sub-confluent cultures were maintained.

Virus Production, Cell Transduction, and Cell Selection

293T cells were transfected with TransitLT1 (Mirus Madison, WI) per the manufacturers protocol with the following modifications. In a separate tube, 9 μg of DNA, 9 μg of PCL Eco and 225 μl of OptiMem were combined. 54 μl of Transit LT1 were added dropwise to 600 μl of OptiMem, and incubated for five minutes before DNA and Transit mix was combined and added to a 10cm plate with 4 million 293T cells. Similar parameters were used for transfecting expression constructs for two fluorescent proteins.

To transduce mK4 cells, the DMEM media was removed and replaced with retrovirus-containing media from the 293T cells. The cells were spun at 500g for 30 minutes, then placed in an incubator for 24 hours, after which the transduction was repeated. All cells except EGFP, mCherry, and tdTomato contained cells were then selected with DMEM containing puromycin (2.0 μg/ml). Cells were considered selected after >95% of non-transduced control mK4 cells plated to similar density as the transduced mK4 cells were dead. mK4 cells transduced with only vectors expressing EGFP, mCherry, and tdTomato (without puromycin resistance) were flow cytometry sorted with a 100 μm nozzle at 25 psi using a BD Biosciences FACSAria II (San Jose, CA) equipped with 5 lasers (355, 405, 488, 561 and 640 nm) which is located in the CCHMC Research Flow Cytometry Core (RFCC). Instrument setup and QC was performed by core facility staff per manufacturer instructions. Positive cells were collected and expanded.

Imaging

Imaging of the cells was performed using the Nikon A1R LUN-V Inverted Confocal Microscope with 6-laser lines (405nm, 445nm, 488nm, 514nm, 561nm, 647nm) and GaAsP detectors located in the CCHMC Confocal Imaging Core (CIC). Cells were treated with trypsin and plated on a #1.5 cover-glass bottom 48 well plate. Cells were imaged 48 hours after plating. Imaging was conducted utilizing the parameters indicated in Table 1.

Table 1 –

List of fluorescent proteins used in the panel. Properties of lasers and filters used in flow cytometry and confocal microscopy experiments are listed. Alternative filters designate a filter change performed to separate fluorescent proteins which would otherwise be detected in the same channel.

| Fluorescent Protein | Excitation Maximum (nm) | Emission Maximum (nm) | Cytometer Channel | Cytometer Excitation Laser (nm) | Cytometer LongPass Filter (nm) | Cytometer BandPass Filter (nm) | Confocal Excitation Laser | Confocal Emission Filter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mTagBFP2 | 399 | 454 | Pacific Blue | 405 | N/A | 450/50 | 405nm | BP 425–475 450/50 |

| mCeruleanS | 433 | 475 | Pacific Blue | 405 | N/A | 450/50 | 445nm | BP 465–505 485/40 |

| Sapphire | 399 | 511 | BV510 | 405 | 505 | 525/50 | 405nm | BP 500–550 525/50 |

| LssmOrange | 437 | 572 | BV510 | 405 | 505 | 525/50 | 488nm | BP 570–620 595/50 |

| EGFP | 488 | 507 | FITC | 488 | 505 | 530/30 | 488nm | BP 500–550 525/50 |

| EGFP (alternative filter) | 488 | 507 | FITC | 488 | 495 | 510/20 | N/A | N/A |

| Venus | 515 | 528 | FITC | 488 | 505 | 530/30 | 5l4nm | BP 518–558 538/40 |

| Venus (alternative filter) | 515 | 528 | PerCP | 488 | 525 | 540/20 | N/A | N/A |

| EYFP | 513 | 527 | FITC | 488 | 505 | 530/30 | 5l4nm | BP 518–558 538/40 |

| mOrange2 | 549 | 565 | PE | 561 | 575 | 582/15 | 561nm | BP 570–620 595/50 |

| mApple | 568 | 592 | PE | 575 | 582/15 | 561nm | BP 570–620 595/50 | |

| tdTomato | 554 | 581 | PE | 561 | 575 | 582/15 | 561nm | BP 570–620 595/50 |

| mCherry | 587 | 610 | PI | 561 | 600 | 610/20 | 561nm | BP 570–620 595/50 |

| TagRFP657 | 611 | 657 | APC-Cy5.5 | 640 | 690 | 710/50 | 647nm | 660nm LP |

| mIFP | 683 | 704 | APC-Cy5.5 | 640 | 690 | 710/50 | 647nm | 660nm LP |

Flow Cytometry and Data Analysis

Flow cytometry was conducted using a BD LSRFortessa located in the CCHMC Research Flow Cytometry Core (RFCC). Instrument QC was performed daily by core facility staff, per manufacturer instructions. The instrument configuration consisted of 5 lasers (355 nm (20mW), 405 nm (50mW), 488 nm (50mW), 561 nm (50mW), and 640 nm (40mW)) and 20 parameters (FSC, SSC and 18 fluorescence detectors) with optical filters as listed in Table 1. Prior to analysis, cells were washed twice in PBS with 2% Fetal Bovine Serum and then filtered. Non-transfected or non-transduced cells were used as a negative control. Data files were exported and analyzed via FlowJo v10.4 (FlowJo LLC). Sensitivity Index (SI) gives a value for the detection sensitivity of a fluorescent protein using a specific laser and filter set. We calculated SI using the following formula: SI = (median fluorescent cells - median non-expressing cells) / (robust SD) where robust SD = (84 percentile non-expressing cells) / (median non-expressing cells) [17]. Spillover spread [55] was calculated in FlowJo.

Results

Imaging of Fluorescent Protein Expression by Microscopy

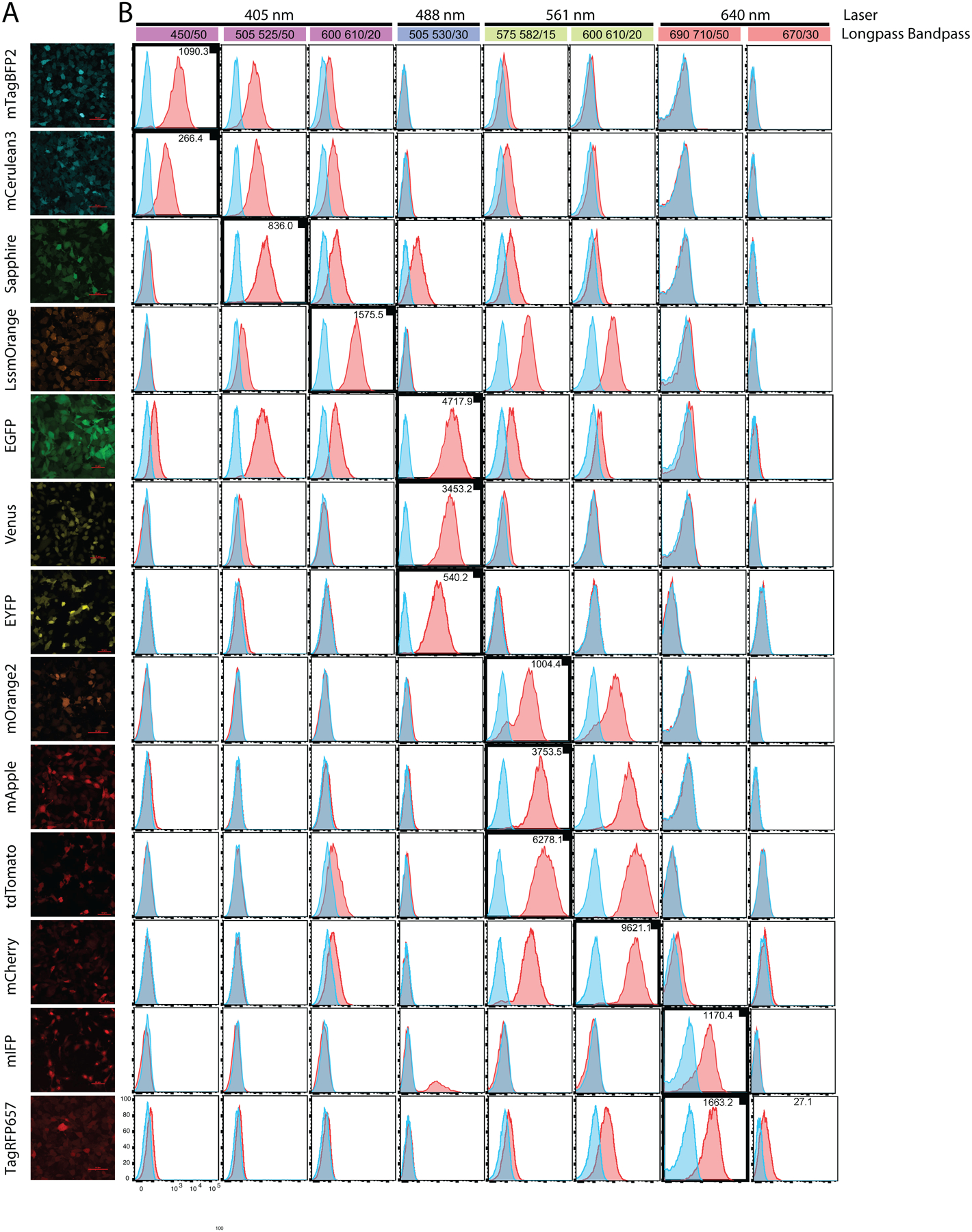

A murine kidney cell line (mK4) was transduced with viral vectors expressing each of the fluorescent proteins (Table 1). Cells were examined via confocal microscope (Fig 1A) by plating into individual wells of a #1.5 cover-glass bottom 48 well plate in indicator-dye-free media. Laser exposure was minimized to avoid photobleaching of the fluorescent proteins. The PMT gains were adjusted so that fluorescence intensity was within the linear range of the PMT detectors across fluorescent proteins. As expected, each well containing transduced cells displayed detectable fluorescence (Table 1).

Figure 1 – Analysis of fluorescent protein brightness and spectral overlap.

(A) Representative confocal images of mK4 cells transduced with a viral vector encoding a single fluorescent protein. (B) Colored bars represent laser wavelengths (as noted). Emission filters used to detect fluorescent proteins listed in colored bar. Details of optical configuration found in Table 1. Histograms generated from data on mK4 cells transduced with a viral vector encoding a single fluorescent protein. Bolded histograms (with small black box) indicate detection channel for the fluorescent protein based on its reported max excitation and emission spectra. Sensitivity Index (SI) for each fluorescent protein is indicated (top right of histogram), and was calculated as described in the Materials and Methods. No compensation was applied to allow visualization of spectral overlap levels in the other channels.

Characterization of Individual Fluorescent Proteins by Flow Cytometry

Once we confirmed fluorescent protein expression via microscopy, we assessed each protein utilizing flow cytometry. All fluorescent protein expression was driven by the MSCV-retroviral-vector LTR to achieve similar protein levels. To compare the relative brightness of each protein, we calculated the Sensitivity Index (SI) as indicated in the histogram plots of each in select channels (Fig 1B). SI gives a value for the detection sensitivity of a fluorescent protein when using a specific laser and filter set. SI is also influenced by instrument sensitivity and PMT voltage as well as auto-fluorescence based on cell type. To observe signal and predict potential spillover we acquired data in all commonly used channels. We noted that mCherry and tdTomato displayed the best detection sensitivity in their indicated channels. EGFP, mApple and Venus displayed a moderate level of sensitivity compared to the other proteins. LssmOrange, mTagBFP2 and mIFP displayed a lower level of sensitivity while Sapphire, EYFP, Cerulean and TagRFP657 had the lowest sensitivity of the proteins tested. From these results, we concluded that the fluorescent proteins with the highest SI values were the best candidates as reporters for low expression targets. However, we observed contribution into neighboring PMTs for some of the fluorescent proteins. To determine the best candidates that would minimize fluorescence spillover in a multicolor flow panel, we focused on commonly used fluorescent proteins that were distributed over 405 nm, 488 nm, 640 nm and 561 nm lasers. EGFP, Venus, EYFP, mCherry, mApple and tdTomato were chosen because their prevalence in literature. With the 488 and 561 nm lasers occupied by the aforementioned proteins, we focused on mTagBFP2 for the 405 nm laser and TagRFP657, and mIFP for the 640 nm laser.

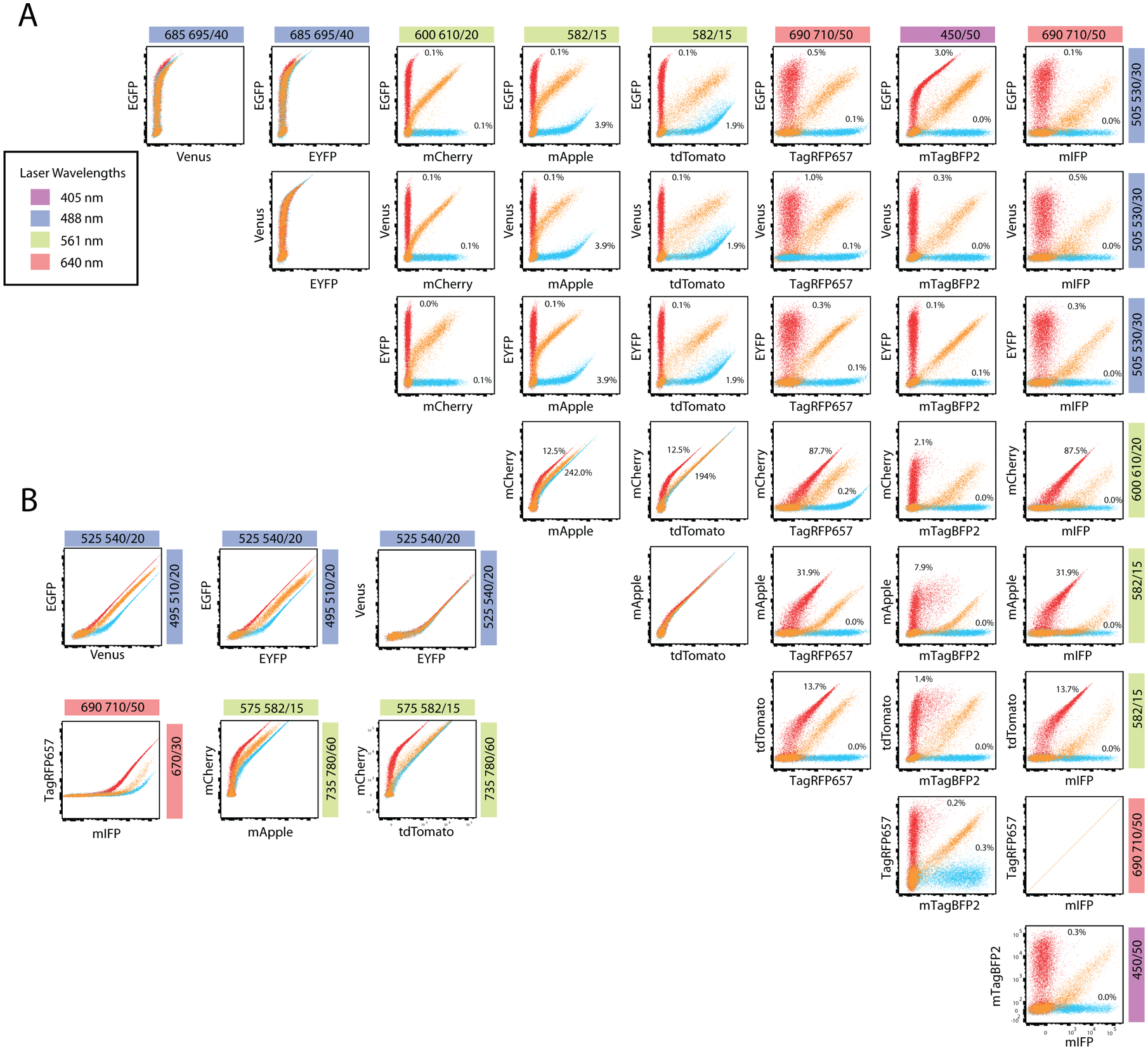

Co-Expression of Fluorescent Proteins Revealed Five Optimal Proteins

293T cells were transduced with combinations of viral vectors and fluorescence was assayed after 48 hours. We assessed the feasibility of detecting a single fluorescence signal when co-expressing two fluorescent proteins in one cell as well as testing that coexpression did not affect the expression of either fluorescent protein. We wanted to identify proteins with relatively low fluorescence spillover and spreading error to facilitate detection of low-level signals and to allow easy implementation into multicolor flow panels. To assess spectral overlap and the efficacy of combining certain fluorescent proteins into a single panel, we calculated compensation values and a spillover spreading matrix (SSM) (Fig 2A, Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Fig 2). EGFP, a fluorescent protein with relatively high SI, displayed little spectral overlap or spillover spreading with every combination except for TagBFP2, with only moderate compensation and spillover spreading (3.0% and 1.97). In addition, no other proteins exhibited significant spillover nor spreading into the GFP channel indicating that eGFP and any of the other proteins tested can be coexpressed without significant impact on resolution. Venus and YFP also exhibited little spectral overlap or spillover spreading into the other channels, however YFP expression was much dimmer than that of Venus and eGFP. Based on this data, eGFP and Venus are most compatible in a multicolor panel. Both mCherry and mApple contributed significant fluorescence spillover and spreading into the red laser channel used to detect TagRFP657 and mIFP. Spreading error was also very high for mApple into the violet laser used to detect mTagBFP2. In contrast, dTomato performed moderately better in this combination. While dTomato is detected in a separate channel than mCherry, there is significant overlap and it is preferable to use dTomato and not both. Both TagRFP657 and mIFP presented little spectral overlap or spreading error in combination with the other fluorescent proteins. But as these fluorescent proteins are detected in the same channel, only one can be utilized. We note that TagRFP657 has a higher SI (Fig 1) and, therefore, is preferable over mIFP. Finally, mTagBFP2, while only moderately bright based on the SI, was easily compatible with the other fluorescent proteins based on its spectral overlap and minimal spillover spreading. Alternative filter selections made the detection of individual signals from EGFP-Venus and EGFP-EYFP signals co-expressing cells possible (Fig 2B). As expected, separation of Venus and EYFP when they are co-expressed is not possible. Alternate filters selections also allowed for the separation of mCherry-mApple signals, as well as TagRFP657-mIFP signals at high fluorescence intensities (Fig 2B). Detecting mCherry-tdTomato co-expressing cells with different filters showed a slight increase in separation from the original filter choices. Most of the fluorescent proteins tested could be expressed with, and separated from, each other. Care should be taken not to combine fluorescent proteins that heavily contribute to or have high spillover spread in other channels in use. From these data, EGFP, Venus, mTagBFP2, TagRFP657 and mIFP emerge as the best candidates for creating a multicolor flow panel (Fig 2). We suggest that 3 fluorescent proteins can be easily combined (EGFP or Venus, mTagBFP2 and either mIFP or TagRFP657) without significant compensation or spillover spread (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 2 – Specificity of fluorescent protein co-expression.

Colored bars represent laser wavelengths (inset, left). Emission filters used to detect fluorescent proteins listed in colored bar. (A-B) Viral vectors expressing the two fluorescent proteins indicated were co-transfected in 293T cells alone or together. Plots for co-expression (orange) were overlaid with single fluorescent protein expression data (red or blue). (A) Compensation values are indicated, however, plots are displayed without compensation applied. (B) Alternative emission filters for the detection of EYFP/Venus with EGFP; RFP657 with mIFP; mApple with mCherry; and mCherry with tdTomato. No compensation was applied to allow visualization of spectral overlap levels in the other channels.

Discussion

Generating knock-in gene-expression or fusion-protein reporters is now more tractable because of recent advances in genome engineering. The objective of this study was to provide flow cytometry data on common fluorescent proteins to understand their utility in multicolor flow panels consisting of more than one knock-in reporter. To construct this list, we selected fluorescent proteins that would fit a general cytometer, and opted for monomeric proteins so that they could be utilized as fusion proteins. Importantly, we wanted to ensure that the fluorescent proteins could function as accurate reporters even when expressed at low levels (in the context of a second or third fluorescent protein).

Both EGFP and Venus demonstrated good performance and compatibility with relatively high SI values, minimal spectral overlap and low spillover spread values. We note that mApple, tdTomato, and mCherry, while having high SI, exhibited spillover into adjacent PMTs, and have the highest spillover spread values of the fluorescent proteins from Fig 2 making them less desirable, particularly for resolving dim signals. Specifically, five proteins: EGFP, Venus, mTagBFP2, mIFP, and TagRFP657, can be easily utilized (EGFP or Venus, mTagBFP2 and either mIFP or TagRFP657). Venus represents a good alternative to EGFP in a multicolor panel. mTagBFP2 is especially versatile based on the data shown here.

While our initial question concerned selection of optimal fluorescent proteins to use for generating new reporter constructs, these data can also inform combinations of existing reporters. For example, if EGFP must be used, the most optimal combination would be EGFP, mTagBFP2, and mTagRFP657. While EYFP is outdated and relatively dim, it could be easily combined with the fluorescent proteins tested here. tdTomato and EGFP also make a good combination due to minimal spillover and spreading error. Moreover, the compensation values illustrated within the plots in Figure 2 demonstrate other possible two-color combinations that could be separated easily. The purpose of our study, however, was to identify fluorescent proteins which work exceptionally well together with a minimal need to apply compensation and while resolving low intensity expression. We suggest that three fluorescent proteins can easily be combined and more colors can be selected based on the data shown. While sensitivity, spectral overlap and spillover spread will be similar in cytometers with similar configurations, instrument variations may effect the performance of fluorescent proteins. Autofluorescence contributed by cell type is also an important consideration since it will directly effect the sensitivity index of the fluorescent protein and, therefore, resolution of dim signals. Additionally, the approach described here can be used to evaluate newer proteins such as mScarlet or mNeonGreen [17, 33]. These are similar to mApple and Venus (respectively) and while they are reportedly bright, utility in multicolor panels would need to be determined.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1 - Representative gating scheme. Cells were gated on scatter parameters, then single cells were selected using the height and width pulses of FSC and SSC, respectively. Single cells were displayed on all subsequent histograms or dot plots.

Supplementary Figure 2 – Specificity of fluorescent protein co-expression. Colored bars represent laser wavelengths (inset, left). Emission filters used to detect fluorescent proteins listed in colored bar. (A-B) Viral vectors expressing the two fluorescent proteins indicated were co-transfected in 293T cells alone or together. Plots for co-expression (orange) were overlaid with single fluorescent protein expression data (red or blue). (B) Alternative emission filters for the detection of EYFP/Venus with EGFP; RFP657 with mIFP; mApple with mCherry; and mCherry with tdTomato. Compensation was calculated in FlowJo v10.4 and applied to flow plots.

Supplementary Table 1 – Spillover Spread Matrix of the fluorescent proteins ustilized in the co-expression assay of Fig 2. The SSM was calculated using FlowJo and values were compared. Emission filters used to detect fluorescent proteins listed in colored bar. Spillover spreading is expressed as the standard deviation of the spillover value into the designated channel.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge support from the Katie Linz Foundation (to D.H.) and a POST award from Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation (to B. K.) and RO1HL122661 (to H.L.G.)

References

- 1.Chalfie M, GFP: lighting up life (Nobel Lecture). Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 2009. 48(31): p. 5603–5611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shimomura O, Discovery of green fluorescent protein (GFP)(Nobel Lecture). Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 2009. 48(31): p. 5590–5602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsien RY, Constructing and exploiting the fluorescent protein paintbox (Nobel Lecture). Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 2009. 48(31): p. 5612–5626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimomura O, Johnson FH, and Saiga Y, Extraction, purification and properties of aequorin, a bioluminescent protein from the luminous hydromedusan, Aequorea. Journal of cellular and comparative physiology, 1962. 59(3): p. 223–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matz MV, et al. , Fluorescent proteins from nonbioluminescent Anthozoa species. Nature biotechnology, 1999. 17(10): p. 969–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shagin DA, et al. , GFP-like proteins as ubiquitous metazoan superfamily: evolution of functional features and structural complexity. Molecular biology and evolution, 2004. 21(5): p. 841–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deheyn DD, et al. , Endogenous green fluorescent protein (GFP) in amphioxus. The Biological Bulletin, 2007. 213(2): p. 95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shu X, et al. , Mammalian expression of infrared fluorescent proteins engineered from a bacterial phytochrome. Science, 2009. 324(5928): p. 804–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumagai A, et al. , A bilirubin-inducible fluorescent protein from eel muscle. Cell, 2013. 153(7): p. 1602–1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hawley TS, Hawley RG, and Telford WG, Fluorescent Proteins for Flow Cytometry. Curr Protoc Cytom, 2017. 80: p. 9 12 1–9 12 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaner NC, et al. , Improved monomeric red, orange and yellow fluorescent proteins derived from Discosoma sp. red fluorescent protein. Nature biotechnology, 2004. 22(12): p. 1567–1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang J, et al. , Creating new fluorescent probes for cell biology. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology, 2002. 3(12): p. 906–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thorn K, Genetically encoded fluorescent tags. Mol Biol Cell, 2017. 28(7): p. 848–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herzenberg LA, et al. , The history and future of the fluorescence activated cell sorter and flow cytometry: a view from Stanford. Clinical chemistry, 2002. 48(10): p. 1819–1827. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bajar BT, et al. , Fluorescent indicators for simultaneous reporting of all four cell cycle phases. Nature Methods, 2016. 13(12): p. 993–996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bajar BT, et al. , Improving brightness and photostability of green and red fluorescent proteins for live cell imaging and FRET reporting. Scientific reports, 2016. 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bindels DS, et al. , mScarlet: a bright monomeric red fluorescent protein for cellular imaging. Nature Methods, 2017. 14(1): p. 53–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chiang C-Y, et al. , Blue fluorescent protein derived from the mutated purple chromoprotein isolated from the sea anemone Stichodactyla haddoni. Protein Engineering Design and Selection, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu D, et al. , An improved monomeric infrared fluorescent protein for neuronal and tumour brain imaging. Nature communications, 2014. 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chu J, et al. , A bright cyan-excitable orange fluorescent protein facilitates dual-emission microscopy and enhances bioluminescence imaging in vivo. Nature biotechnology, 2016. 34(7): p. 760–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dean KM, et al. , High-speed multiparameter photophysical analyses of fluorophore libraries. Analytical chemistry, 2015. 87(10): p. 5026–5030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Erard M, et al. , Minimum set of mutations needed to optimize cyan fluorescent proteins for live cell imaging. Molecular BioSystems, 2013. 9(2): p. 258–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghosh S, et al. , Blue protein with red fluorescence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2016. 113(41): p. 11513–11518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goedhart J, et al. , Structure-guided evolution of cyan fluorescent proteins towards a quantum yield of 93%. Nature communications, 2012. 3: p. 751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoi H, et al. , An engineered monomeric Zoanthus sp. yellow fluorescent protein. Chemistry & biology, 2013. 20(10): p. 1296–1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lam AJ, et al. , Improving FRET dynamic range with bright green and red fluorescent proteins. Nature methods, 2012. 9(10): p. 1005–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laviv T, et al. , Simultaneous dual-color fluorescence lifetime imaging with novel red-shifted fluorescent proteins. Nature Methods, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matela G, et al. , A far-red emitting fluorescent marker protein, mGarnet2, for microscopy and STED nanoscopy. Chemical Communications, 2017. 53(5): p. 979–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piatkevich KD, et al. , Extended Stokes shift in fluorescent proteins: chromophore–protein interactions in a near-infrared TagRFP675 variant. Scientific reports, 2013. 3: p. 1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pletnev VZ, et al. , Structure of the red fluorescent protein from a lancelet (Branchiostoma lanceolatum): a novel GYG chromophore covalently bound to a nearby tyrosine. Acta Crystallographica Section D: Biological Crystallography, 2013. 69(9): p. 1850–1860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ren H, et al. , Cysteine Sulfoxidation Increases the Photostability of Red Fluorescent Proteins. ACS Chemical Biology, 2016. 11(10): p. 2679–2684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodriguez EA, et al. , A far-red fluorescent protein evolved from a cyanobacterial phycobiliprotein. nAture methods, 2016. 13(9): p. 763–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shaner NC, et al. , A bright monomeric green fluorescent protein derived from Branchiostoma lanceolatum. Nature methods, 2013. 10(5): p. 407–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shcherbakova DM, et al. , Bright monomeric near-infrared fluorescent proteins as tags and biosensors for multiscale imaging. Nature Communications, 2016. 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shcherbakova DM, et al. , An orange fluorescent protein with a large Stokes shift for single-excitation multicolor FCCS and FRET imaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2012. 134(18): p. 7913–7923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shcherbakova DM and Verkhusha VV, Near-infrared fluorescent proteins for multicolor in vivo imaging. Nature methods, 2013. 10(8): p. 751–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shemiakina I, et al. , A monomeric red fluorescent protein with low cytotoxicity. Nature communications, 2012. 3: p. 1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang J, et al. , mBeRFP, an improved large stokes shift red fluorescent protein. PloS one, 2013. 8(6): p. e64849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang Z, et al. Time-resolved flow cytometry for lifetime measurements of near-infrared fluorescent proteins. in CLEO: Science and Innovations. 2016. Optical Society of America. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu D, et al. , A naturally monomeric infrared fluorescent protein for protein labeling in vivo. Nature methods, 2015. 12(8): p. 763–765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu D, et al. , A naturally monomeric infrared fluorescent protein for protein labeling in vivo. Nat Methods, 2015. 12(8): p. 763–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heppert JK, et al. , Comparative assessment of fluorescent proteins for in vivo imaging in an animal model system. Mol Biol Cell, 2016. 27(22): p. 3385–3394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shaner NC, Steinbach PA, and Tsien RY, A guide to choosing fluorescent proteins. Nat Methods, 2005. 2(12): p. 905–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Telford WG, et al. , Flow cytometry of fluorescent proteins. Methods, 2012. 57(3): p. 318–330. 45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nagai T, et al. , A variant of yellow fluorescent protein with fast and efficient maturation for cell-biological applications. Nature biotechnology, 2002. 20(1): p. 87–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shcherbakova DM, et al. , An orange fluorescent protein with a large Stokes shift for single-excitation multicolor FCCS and FRET imaging. J Am Chem Soc, 2012. 134(18): p. 7913–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morozova KS, et al. , Far-red fluorescent protein excitable with red lasers for flow cytometry and superresolution STED nanoscopy. Biophys J, 2010. 99(2): p. L13–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shaner NC, et al. , Improving the photostability of bright monomeric orange and red fluorescent proteins. Nat Methods, 2008. 5(6): p. 545–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cubitt AB, Woollenweber LA, and Heim R, Understanding Structure—Function Relationships in the Aequorea victoria Green Fluorescent Protein. Methods in cell biology, 1998. 58: p. 19–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Subach OM, et al. , An enhanced monomeric blue fluorescent protein with the high chemical stability of the chromophore. PLoS One, 2011. 6(12): p. e28674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kremers G-J, et al. , Cyan and Yellow Super Fluorescent Proteins with Improved Brightness, Protein Folding, and FRET Förster Radius†. Biochemistry, 2006. 45(21): p. 6570–6580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Markwardt ML, et al. , An improved cerulean fluorescent protein with enhanced brightness and reduced reversible photoswitching. PLoS One, 2011. 6(3): p. e17896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang T-T, Cheng L, and Kain SR, Optimized codon usage and chromophore mutations provide enhanced sensitivity with the green fluorescent protein. Nucleic acids research, 1996. 24(22): p. 4592–4593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee S, Lim WA, and Thorn KS, Improved blue, green, and red fluorescent protein tagging vectors for S. cerevisiae. PloS one, 2013. 8(7): p. e67902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nguyen R, et al. , Quantifying spillover spreading for comparing instrument performance and aiding in multicolor panel design. Cytometry A, 2013. 83(3): p. 306–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1 - Representative gating scheme. Cells were gated on scatter parameters, then single cells were selected using the height and width pulses of FSC and SSC, respectively. Single cells were displayed on all subsequent histograms or dot plots.

Supplementary Figure 2 – Specificity of fluorescent protein co-expression. Colored bars represent laser wavelengths (inset, left). Emission filters used to detect fluorescent proteins listed in colored bar. (A-B) Viral vectors expressing the two fluorescent proteins indicated were co-transfected in 293T cells alone or together. Plots for co-expression (orange) were overlaid with single fluorescent protein expression data (red or blue). (B) Alternative emission filters for the detection of EYFP/Venus with EGFP; RFP657 with mIFP; mApple with mCherry; and mCherry with tdTomato. Compensation was calculated in FlowJo v10.4 and applied to flow plots.

Supplementary Table 1 – Spillover Spread Matrix of the fluorescent proteins ustilized in the co-expression assay of Fig 2. The SSM was calculated using FlowJo and values were compared. Emission filters used to detect fluorescent proteins listed in colored bar. Spillover spreading is expressed as the standard deviation of the spillover value into the designated channel.