Abstract

Background:

Coal miners with totally disabling pneumoconiosis are eligible for benefits through the Federal Black Lung Benefits Program (FBLP). We identify the causes of death among Medicare beneficiaries with a claim for which the FBLP was the primary payer and compare these causes of death to all deceased Medicare beneficiaries to better understand elevated death and disease among miners with occupational respiratory exposures.

Methods:

From 1999 to 2016 Medicare data, we extracted beneficiary and National Death Index data for 28,003 beneficiaries with an FBLP primary payer claim. We summarized the International Classification of Diseases, Clinical Modification 10th revision-coded underlying causes of death and entity-axis multiple causes of death for 22,242 deceased Medicare beneficiaries with an FBLP primary payer Medicare claim and compared their causes of death to the deceased Medicare beneficiary population.

Results:

Among deceased FBLP beneficiaries, the three leading underlying causes of death were chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, unspecified (J44.9, 10.1%), atherosclerotic heart disease (I25.1, 9.3%), and coal workers' pneumoconiosis (CWP) (J60, 9.2%). All diseases of the respiratory system combined (J00–J99) were the underlying cause of death for 29.1% of all beneficiaries, with pneumoconioses (J60–J64) as the underlying cause for 11.0% of all beneficiaries.

Conclusions:

Coal miners enrolled in Medicare with an FBLP primary payer claim were more likely to have specific respiratory and cardiovascular diseases listed as a cause of death than deceased Medicare beneficiaries overall, and were also more likely to die from CWP or any pneumoconioses.

Keywords: compensation, lung disease, mortality, pneumoconiosis, surveillance

1 ∣. INTRODUCTION

Mortality data can be used as part of public health surveillance to monitor disease and identify health disparities in populations.1 Monitoring pneumoconiosis mortality and other causes of death among coal miners enhances our understanding of death and disease among these workers with occupational respiratory exposures. Mortality from pneumoconiosis and other causes of death among coal miners who are beneficiaries in the Federal Black Lung Benefits Program (FBLP) has not been reported. The FBLP provides financial and medical benefits to U.S. coal miners with totally disabling pneumoconiosis arising from their coal mine employment.2,3 For FBLP eligibility purposes, the term “pneumoconiosis” is defined as “a chronic dust disease of the lung and its sequelae, including respiratory and pulmonary impairments, arising out of coal mine employment.”4 Coal miners applying for benefits through the FBLP receive a physician examination, chest radiograph, pulmonary function test, and arterial blood gas test to determine if they have completely disabling respiratory conditions arising from coal mine employment.2

While Medicare is the primary federal health insurance for persons aged ≥ 65 years in the United States as well as other eligible individuals, Medicare claims data also include those for which specific non-Medicare payers have primary responsibility for claim payment.5,6 The FBLP has primary responsibility for Medicare claims related to a qualified coal miner's totally disabling pneumoconiosis.2,6 In this descriptive study, we use Medicare and National Death Index (NDI) data from 1999 to 2016 to identify the causes of death for coal miners enrolled in Medicare who had at least one FBLP primary payer claim and compare their causes of death to the deceased Medicare beneficiary population.

2 ∣. METHODS

We accessed Medicare claims data files and Medicare beneficiary data files through the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Virtual Research Data Center.7 From the 1999–2016 Medicare claims files, we extracted final action fee-for-service (also known as Medicare parts A and B) institutional and non-institutional claims for which the FBLP was listed as the primary payer and excluded denied claims.2,6 Claims for which the FBLP was listed as the primary payer were linked to master beneficiary summary file (MBSF) base and NDI segments using the beneficiary ID for the 28,003 Medicare beneficiaries with a FBLP primary payer claim.7-9 NDI segment data for all deceased Medicare beneficiaries from 1999 to 2016 was linked to MBSF Base segment data from the beneficiary's death year using the beneficiary ID.7-9

From the MBSF base segment, we extracted information on a beneficiary's date of birth, sex, race or ethnic origin, and reason for Medicare entitlement.8 Race or ethnic origin groupings included white, black, other (Asian, Hispanic, North American Native, and other), and unknown. A beneficiary's original reason for Medicare entitlement (aged ≥65 years, aged <65 years and receiving Social Security Administration disability insurance benefits for 24 consecutive months, or any beneficiary with end stage renal disease or end stage renal disease and disability insurance benefits) as well as current reason for entitlement the year of their death were identified from base segment data.

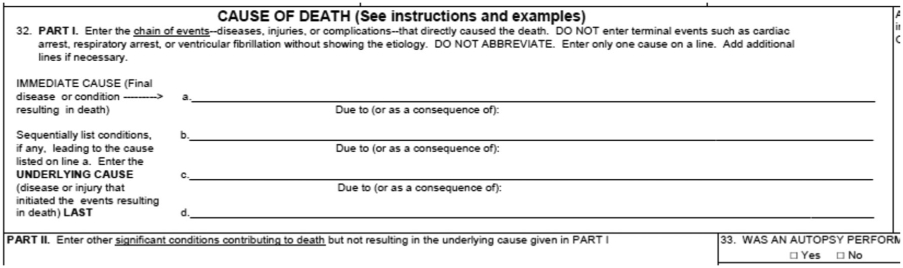

The MBSF NDI segment includes death certificate information from the NDI database, which is a centralized database of death records, housed by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS).9,10 Of the 28,003 Medicare beneficiaries with a FBLP primary payer claim, 22,242 were deceased. NDI segment data were used to determine beneficiary age at death (calculated as the difference between a beneficiary's NDI death date and MBSF base segment birth date), years of Medicare insurance coverage (difference between a beneficiary's NDI death date and MBSF base segment Medicare coverage start date), and state of death. Multiple causes of death were extracted for all 35,893,251 deceased Medicare beneficiaries from 1999 to 2016. Multiple causes of death (up to eight total causes from 1999 to 2006 and up to 20 total causes from 2007 to 2016) include a single underlying cause of death, “the disease or injury which initiated the train of events leading directly to death, or the circumstances of the accident or violence which produced the fatal injury” and may include additional conditions leading to the underlying cause of death or contributing to death as indicated on the U.S. Standard Certificate of Death (Figure 1).9,11,12 Causes of death are coded according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) and the underlying cause of death is selected from all causes of death listed on a death certificate based on set criteria.9,12

FIGURE 1.

Excerpt from the U.S. Standard Certificate of Death

The most common underlying causes of death for FBLP primary payer Medicare beneficiaries were identified, and the percentage of all 1999–2016 deceased Medicare beneficiaries with these underlying causes of death were also identified for comparison. Since multiple causes of death are frequently listed on death certificates, we also summarized multiple causes of death which was any mention of a particular ICD-10-CM code on the death certificate (including as the underlying cause).

Entity axis coded causes of death rather than record axis codes (which are edited and audited by NCHS) were used in this analysis because they preserve original cause of death conditions written on the death certificate. For comparison, we also analyzed NDI record axis multiple cause of death codes developed by algorithms in which duplicate and contradictory cause of death codes are removed.12 In this study, ICD-10-CM codes used to identify pneumoconioses as a cause of death included J60 (coal workers' pneumoconiosis [CWP]), J61 (pneumoconiosis due to asbestosis and other mineral fibers), J62 (pneumoconiosis due to dust containing silica), J63 (pneumoconiosis due to other inorganic dusts), and J64 (unspecified pneumoconiosis). Pearson's χ2 tests were used to compare cause of death frequencies between deceased 1999–2016 Medicare beneficiaries and deceased 1999–2016 FBLP primary payer Medicare beneficiaries and were considered significant at p ≤ .05. Dependent χ2 comparisons between FBLP primary payer Medicare beneficiaries and total deceased Medicare beneficiaries from 1999 to 2016 were made without correcting for dependent comparisons because FBLP primary payer Medicare beneficiaries represented 0.06% of the deceased Medicare beneficiaries.13

3 ∣. RESULTS

Among the 28,003 Medicare beneficiaries with a claim for which the FBLP was the primary payer during 1999–2016, we identified 22,242 (79.4%) deceased beneficiaries. The demographic and Medicare enrollment characteristics of these beneficiaries and 35 million deceased Medicare beneficiaries are shown in Table 1. Most (95.7%) deceased FBLP primary payer beneficiaries were aged ≥65 years at the time of their death, male (93.6%), white (94.6%), and 70% were from the four states: Pennsylvania (25.5%), West Virginia (18.6%), Kentucky (16.0%), and Virginia (10.7%). The demographic characteristics of workers in the U.S. coal mining industry are predominately male, of white race or ethnic origin, and living in Appalachian states (e.g., Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Kentucky, and Virginia).14 However, the demographic characteristics of deceased Medicare beneficiaries included a lower percent of males (53.4% females), whites (85.9%), and those living in Appalachian states compared to the U.S. coal miners. The original reason for Medicare entitlement for half of these FBLP primary payer beneficiaries (50.1%) was they had received Social Security Administration disability insurance benefits for 24 consecutive months, and the current reason for entitlement at the time of their first FBLP primary payer claim for most beneficiaries (92.6%) was having an age ≥65 years. However, for most deceased Medicare beneficiaries, the original reason and current reason for Medicare entitlement was age ≥65 years (80.9% and 91.3%, respectively). Approximately two-thirds (65.8%) of FBLP primary payer beneficiaries were enrolled in Medicare for longer than twenty years before death while only 38.9% of all Medicare beneficiaries were enrolled in Medicare for longer than twenty years before death.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and Medicare enrollment characteristics of deceased Medicare beneficiaries with a FBLP primary payer claim and all deceased Medicare beneficiaries, 1999–2016

| Characteristics | Deceased FBLP primary payer beneficiaries |

Deceased Medicare beneficiaries |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 22,242 | Percent | n = 35,893,251a | Percent | |

| Age group at death (years) | ||||

| 18–44 | 57 | 0.3 | 351,412 | 1.0 |

| 45–64 | 896 | 4.0 | 2,576,715 | 7.2 |

| 65–74 | 2689 | 12.1 | 7,273,275 | 20.3 |

| 75–84 | 8049 | 36.2 | 11,642,008 | 32.5 |

| 85+ | 10,551 | 47.4 | 14,035,739 | 39.1 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 20,822 | 93.6 | 16,720,988 | 46.6 |

| Female | 1,420 | 6.4 | 19,158,781 | 53.4 |

| Race/ethnic originb | ||||

| White | 21,045 | 94.6 | 30,566,629 | 85.2 |

| Black | 809 | 3.6 | 3,552,005 | 9.9 |

| Other | 355 | 1.6 | 1,642,070 | 4.6 |

| Unknown | 33 | 0.2 | 119,133 | 0.3 |

| NDI state of death | ||||

| Pennsylvania | 5666 | 25.5 | 1,924,126 | 5.4 |

| West Virginia | 4146 | 18.6 | 307,605 | 0.9 |

| Kentucky | 3548 | 16.0 | 590,953 | 1.7 |

| Virginia | 2376 | 10.7 | 830,260 | 2.3 |

| Other states | 6506 | 29.3 | 32,226,893 | 89.8 |

| Medicare coverage (years) | ||||

| 0–10 | 1797 | 8.1 | 9,178,358 | 25.6 |

| 11–20 | 5812 | 26.1 | 12,755,539 | 35.6 |

| 21–30 | 10,829 | 48.7 | 11,488,580 | 32.0 |

| 31+ | 3804 | 17.1 | 2,457,294 | 6.9 |

| Original entitlement reason | ||||

| Aged ≥65 years | 10,940 | 49.2 | 29,023,133 | 80.9 |

| Disability | 11,134 | 50.1 | 6,425,859 | 17.9 |

| End stage renal | 168 | 0.8 | 430,845 | 1.2 |

| disease | ||||

| Current entitlement reasonc | ||||

| Aged ≥65 years | 21,200 | 95.3 | 32,770,510 | 91.3 |

| Disability | 882 | 4.0 | 2,735,954 | 7.6 |

| End stage renal disease | 155 | 0.7 | 373,373 | 1.0 |

Abbreviations: FBLP, Federal Black Lung Benefits Program; NDI, National Death Index.

Of 35,893,251 Medicare beneficiaries from 1999–2016 with NDI segment data, master beneficiary summary file Base segment data from the year of a beneficiary's death were available for 35,879,837 beneficiaries. Age group at death was missing for 688, sex was unknown for 68, and Medicare coverage years was missing for 66.

Other race/ethnic origin included Asian, Hispanic, North American Native, and other.

Current entitlement reason was missing for five beneficiaries the year of their death.

The ten most common underlying causes of death for FBLP primary payer beneficiaries (summarized in Table 2A) account for 54.4% of all underlying causes of death in these beneficiaries. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, unspecified (J44.9) was the leading underlying cause of death (10.1%) followed by atherosclerotic heart disease (I25.1, 9.3%), CWP (J60, 9.2%), malignant neoplasm: bronchus or lung, unspecified (C34.9, 7.3%), and acute myocardial infarction, unspecified (I21.9, 6.9%). When compared with the 35.9 million deceased Medicare beneficiaries from 1999 to 2016, these FBLP primary payer beneficiaries had a significantly higher proportion of total deaths from seven of these ten underlying causes of death including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, unspecified (10.1% vs. 4.8%) and CWP (9.2 vs. 0.01%).

TABLE 2A.

Causes of death for Medicare beneficiaries with a FBLP primary payer claim compared with all Medicare beneficiaries, 1999–2016

| Underlying cause of death |

Multiple cause of deatha |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medicare beneficiaries with a FBLP primary payer claim (n = 22,242) |

All Medicare beneficiaries (n = 35,893,251) |

Medicare beneficiaries with a FBLP primary payer claim (n = 22,242) |

All Medicare beneficiaries (n = 35,893,251) |

|||

| Cause of death (ICD-10-CM codes) | N | % of total deaths | % of total deaths | N | % of total deaths | % of total deaths |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, unspecified (J44.9) | 2254 | 10.1* | 4.8 | 6717 | 30.2* | 10.9 |

| Atherosclerotic heart disease (I25.1) | 2077 | 9.3* | 8.6 | 4701 | 21.1* | 15.9 |

| Coal workers' pneumoconiosis (J60) | 2037 | 9.2* | 0.01 | 4048 | 18.2* | 0.03 |

| Malignant neoplasm: bronchus or lung, unspecified (C34.9) | 1630 | 7.3* | 6.0 | 1859 | 8.4* | 6.5 |

| Acute myocardial infarction, unspecified (I21.9) | 1541 | 6.9* | 6.0 | 2095 | 9.4* | 7.7 |

| Pneumonia, unspecified (J18.9) | 617 | 2.8* | 2.3 | 3208 | 14.4* | 8.3 |

| Congestive heart failure (I50.0) | 611 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 3835 | 17.2* | 12.8 |

| Stroke, not specified as hemorrhage or infarction (I64) | 492 | 2.2* | 3.5 | 1171 | 5.3* | 6.6 |

| Malignant neoplasm of prostate (C61) | 430 | 1.9* | 1.4 | 779 | 3.5* | 2.0 |

| Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, so described (I25.0) | 422 | 1.9* | 2.4 | 791 | 3.6 | 3.3 |

Abbreviations: FBLP, Federal Black Lung Benefits Program; ICD-10-CM, International Classification of Diseases, Clinical Modification 10th revision.

Multiple causes of death include the underlying cause of death.

p ≤ .05 based on Pearson's χ2 test.

In this study, 83.9% of FBLP beneficiaries had at least two causes of death listed on their death certificate. Specifically, 19.3% of death certificates had two causes, 21.4% had three causes, 17.3% had four causes, and 26.0% had five or more causes listed. Multiple causes of death included chronic conditions such as any mention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, unspecified (J44.9, 30.2%), atherosclerotic heart disease (J44.9, 21.1%), CWP (J60, 18.2%), congestive heart failure (I50.0, 17.2%), and pneumonia, unspecified (J18.9, 14.4%) (Table 2A) for FBLP primary payer beneficiaries. They were more likely to have any mention of nine of these common causes of death compared with all deceased Medicare beneficiaries.

The percentages of total deaths for the causes listed in Table 2A among FBLP primary payer Medicare beneficiaries using record axis cause of death data were generally similar to results using the entity axis coded causes of death. Differences were noted in percentage of total deaths using record axis codes for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, unspecified (27.7%) and pneumonia, unspecified (12.9%).

Table 2b shows that from 1999 to 2016, all diseases of the respiratory system combined (J00–J99) were listed as the underlying cause of death for 29.1% (n = 6466) of the FBLP primary payer Medicare population with any mention of a disease of the respiratory system in 59.7% (n = 13,276) of this population. Pneumoconioses combined (J60–J64) were the underlying cause for 11.0% (n = 2444) with any mention of pneumoconioses in 22.3% (n = 4960). The proportion of deaths due to CWP decreased from 9.9% in 1999 to 5.7% in 2016 (underlying cause), and from 21.4% to 11.6% (multiple cause).

TABLE 2B.

Other combined cause of death groups for 22,242 deceased Medicare beneficiaries with a FBLP primary payer claim, 1999–2016

| Cause of death (ICD-10-CM codes) | Underlying cause of death N |

Percent of total deaths (%) |

Multiple cause of death N |

Percent of total deaths % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diseases of the respiratory system (J00–J99) | 6466 | 29.1 | 13,276 | 59.7 |

| Pneumoconioses (J60–J64) | 2444 | 11.0 | 4960 | 22.3 |

Abbreviation: FBLP, Federal Black Lung Benefits Program; ICD-10-CM, International Classification of Diseases, Clinical Modification 10th revision.

4 ∣. DISCUSSION

We describe the causes of death in a population of Medicare-enrolled coal miners with at least one FBLP primary payer claim and compare their causes of death to all deceased Medicare beneficiaries. Exposure to coal mine dust can lead to a spectrum of cardiovascular, respiratory, and non-respiratory conditions, and in the current study, we found specific cardiovascular and respiratory causes of death were associated with FBLP beneficiaries.15,16 Cardiovascular diseases (i.e., atherosclerotic heart disease; acute myocardial infarction, unspecified; congestive heart failure; stroke, not specified as hemorrhage or infarction; and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, so described) were among the top ten most common underlying causes of death. Cardiovascular causes of death were also reported among Kentucky residents with pneumoconiosis listed as a cause of death, and another study of coal miners reported an increased risk of ischemic heart disease mortality with coal dust exposure.17,18 While cardiovascular diseases could be associated with systemic gas exchange abnormalities in coal miners, cardiovascular comorbidities are prevalent in coal miners.16-20 Miners participating in the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Coal Workers' Health Surveillance Program have a high prevalence of hypertension and obesity, which may or may not be related to mining.19 Furthermore, Medicare beneficiaries with an institutional FBLP primary payer claim from 1999 to 2016 (n = 19,700) had a significantly higher prevalence of hypertension, ischemic heart disease, heart failure, hyperlipidemia, and respiratory comorbidities compared to nearly 34 million 2016 Medicare beneficiaries.20

Diseases of the respiratory system (J00–J99) were the underlying cause of death for 29.1% of miners and listed as a cause of death for 59.7%. In addition to CWP, other diseases of the respiratory system are common in coal miners due to the relationship between coal mine dust exposures and chronic bronchitis, emphysema, respiratory infection, and respiratory failure.16 In our study of coal miners enrolled in Medicare with at least one FBLP primary payer claim during 1999–2016, we identified pneumoconiosis as the underlying cause of death in 11.0% and lung cancer (ICD-10-CM code C34) as the underlying cause of death in 7.4% (n = 1642), with any mention of lung cancer as a cause of death in 8.4% (n = 1871). Another study of 5907 deceased underground U.S. coal miners from between 1969 and 1971 through 2007 identified pneumoconiosis as the underlying cause of death in 6.8% (n = 403) and lung cancer as the underlying cause of death in 9.6% (n = 568), although FBLP beneficiary status was not reported.21

Death certificate data from FBLP Medicare beneficiaries aides in the understanding of pneumoconiosis and other cause mortality among coal miners but death certificates have limitations related to their potential for error, including disease misclassification or omission. Causes of death represent the medical opinion of the medical certifier of death (e.g., coroner, medical examiner, physician, nurse practitioner, or justice of the peace), are based on their access to medical records, laboratory results, occupational history, and autopsy results, and are not validated by medical records. They may include errors or there may be missing information when causes of death are not correctly identified or the chain of events leading to death are not adequately reported.1,22 The death certificate does not include all medical conditions present at death, but instead describes the sequence or process leading to death.23 Therefore, absence of pneumoconiosis on the death certificate does not indicate absence of pneumoconiosis, rather it was not included or recognized as being involved in death. In fact, all FBLP beneficiaries have been determined to have totally disabling pneumoconiosis through a claims process that includes detailed documentation of employment history and a completion of a pulmonary evaluation by an authorized medical professional.2,3 When used for surveillance purposes, mortality data consistently underestimate the cases of occupational lung diseases and the extent of this underestimation has been identified for certain types of pneumoconiosis.22,24 For example, in Michigan, 8% of decedents with confirmed silicosis had any mention of silicosis on their death certificate.24 Available U.S. surveillance data indicated the age-adjusted mortality rate from all pneumoconioses as a cause of death declined from 12.8 per million in 1999 to 6.4 in 2014.25 Specifically, the age-adjusted mortality rate for CWP as a cause of death declined from 4.7 in 1999 to 1.3 in 2014 despite an increase in the national prevalence of radiographic CWP among long-tenured underground coal miners from 5% in the late-1990s to 11% in 2017.26,27 This discrepancy may indicate recent cases of CWP are not yet accounted for in mortality data and could further exemplify underestimation of occupational lung disease in mortality data. In our study, among the 22,242 deceased miners with totally disabling pneumoconiosis, 42.6% (n = 9477) had CWP listed as a diagnosis on a FBLP primary payer claim (data not shown). Among this subset of 9477, we found that 29.3% (2774) had CWP listed as a cause of death, and 35.0% (3321) had any pneumoconiosis listed as a cause of death.

One of the limitations of Medicare claims data is that a beneficiary's occupation or work history is not included, except for coal miners identified using the FBLP primary payer variable. Since occupational exposure to coal mine dust causes specific cardiopulmonary conditions in coal miners, a suitable group of ever employed Medicare beneficiaries for comparison to FBLP primary payer beneficiaries was not available and we opted to use the comparison group of all deceased Medicare beneficiaries to provide context to our findings. Causes of death among Medicare beneficiaries with similar demographic characteristics as the FBLP primary payer beneficiaries (i.e., white, male Medicare beneficiaries from Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Kentucky, and Virginia [n = 1,493,187]) were also compared to deceased FBLP primary payer Medicare beneficiaries. Results of chi-square tests indicated no significant difference in the proportion of FBLP beneficiaries with acute myocardial infarction, unspecified or atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, so described underlying cause of death. There was no significant difference in the proportion of FBLP beneficiaries with malignant neoplasm: bronchus or lung, unspecified; acute myocardial infarction, unspecified; stroke, not specified as hemorrhage or infarction; or malignant neoplasm of prostate multiple cause of death (Table SI).

The 1999–2016 U.S. population mortality data from the National Vital Statistics System listed CWP (ICD-10-CM J60) as the underlying cause of death for 4345 individuals aged ≥15 years (https://wonder.cdc.gov). Our study was limited to Medicare beneficiaries with a FBLP primary payer claim and included approximately half of the 4345 individuals identified in national statistics (n = 2037). Those in the National Vital Statistics System with CWP as the underlying cause of death that were unaccounted for in our study either may not be enrolled in Medicare or may be enrolled in Medicare but not entitled to FBLP benefits. Our results describe the reported burden of occupational respiratory disease and other causes of death among coal miners enrolled in Medicare with a FBLP primary payer claim. These miners were more likely to have specific respiratory and cardiovascular diseases listed as a cause of death compared to all deceased Medicare beneficiaries and were also more likely to die from CWP or any pneumoconioses than deceased Medicare beneficiaries. When the limitations of mortality data and additional surveillance data sources are considered, these data enhance our understanding of death and disease occurrence among coal miners.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Lauren Brewer (NIOSH/CDC) and Jessica Bell (DDPHSS/CDC) for providing helpful comments and critique of the manuscript. This work was supported by the National Occupational Research Agenda, NIOSH, CDC. All authors are employees of the Federal Government and all work was performed as part of their official duties.

DISCLAIMER

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Mention of product names does not imply endorsement by NIOSH/CDC.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

DISCLOSURE BY AJIM EDITOR OF RECORD

John Meyer declares that he has no conflict of interest in the review and publication decision regarding this article.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional Supporting Information may be found online in the supporting information tab for this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brooks EG, Reed KD. Principles and pitfalls: a guide to death certification. Clin Med Res. 2015;12(2):74–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Division of Coal Mine Workers' Compensation. Compliance guide to the Black Lung Benefits Act. https://www.dol.gov/owcp/dcmwc/regs/compliance/blbenact.htm. Accessed 25 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Division of Coal Mine Workers' Compensation. Guide to filing for Black Lung benefits (miner). https://www.dol.gov/owcp/dcmwc/filing_guide_miner.htm. Accessed 25 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4.30 USC 902. Black lung benefits. http://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?path=/prelim@title30/chapter22/subchapter4&edition=prelim. Accessed 25 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare program—general information. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-General-Information/MedicareGenInfo/index.html. Accessed 25 February 2020.

- 6.U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Coordination of benefits & recovery overview. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Coordination-of-Benefits-and-Recovery/Coordination-of-Benefits-and-Recovery-Overview/Overview.html. Accessed 25 February 2020.

- 7.Research Data Assistance Center. Find, request, and use CMS data [ResDac web site]. https://www.resdac.org/. Accessed 25 February 2020.

- 8.Research Data Assistance Center. Master beneficiary summary file (MBSF) base. https://www.resdac.org/cms-data/files/mbsf-base. Accessed 22 January 2019.

- 9.Research Data Assistance Center. Master beneficiary summary file (MBSF): National Death Index (NDI) segment. https://www.resdac.org/cms-data/files/mbsf-ndi/data-documentation. Accessed 25 February 2020.

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Death Index. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ndi/index.htm. Accessed 25 February 2020.

- 11.World Health Organization.International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems-10th Revision. 5th ed. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Center for Health Statistics. National Death Index user's guide. Hyattsville, MD. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayes LJ, Berry G. Comparing the part with the whole: should overlap be ignored in public health measures? J Public Health. 2006;28(3):278–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jansen McWilliams L, Lenart PJ, Lancaster JL, Zeiner JR. National Survey of the mining population part I: employees. 2012. Department of Health and Human Service (National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health) Publication No. 2012-152. http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/mining/UserFiles/works/pdfs/2012-152.pdf. Accessed 25 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmajuk G, Trupin L, Yelin E, Blanc PD. Prevalence of arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis in coal mining counties of the United States. Arthritis Care Res. 2019;71(9):1209–1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petsonk EL, Rose C, Cohen R. Coal mine dust lung disease-new lessons from an old exposure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(11):1178–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beggs JA, Slavova S, Bunn TL. Patterns of pneumoconiosis mortality in Kentucky: analysis of death certificate data. Am J Ind Med. 2015;58(10):1075–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landen D, Wassell J. Coal dust exposure and mortality from ischemic heart disease among a cohort of US coal miners. Am J Ind Med. 2011;53:727–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Casey ML, Fedan KB, Edwards N, et al. Evaluation of high blood pressure and obesity among US coal miners participating in the enhanced coal workers' health surveillance program. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2017;11(8):541–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurth L, Casey M, Schleiff P, Halldin C, Mazurek J, Blackley D. Medicare claims paid by the Federal Black Lung Benefits Program: U.S. Medicare beneficiaries, 1999–2016. J Occup Environ Med. 2019;61:510. 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Graber JM, Stayner LT, Cohen RA, Conroy LM, Attfield MD. Respiratory disease mortality among US coal miners; results after 37 years of follow-up. Occup Environ Med. 2014;71(1):30–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goodwin SS, Stanbury M, Wang ML, Silbergeld E, Parker JE. Previously undetected silicosis in New Jersey decendents. Am J Ind Med. 2003;44:304–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Possible solutions to common problems in death certification. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/writing-cod-statements/death_certification_problems.htm. Accessed 25 February 2020.

- 24.Reilly MJ, Timmer SJ, Rosenman KD. The burden of silicosis in Michigan: 1988–2016. Annals ATS. 2018;15(12):1404–1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. All pneumoconioses: number of deaths, crude and age-adjusted death rates, U.S. residents age 15 and over, 1968–2014. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/eWorld/Grouping/All_Pneumoconioses/91

- 26.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coal workers' pneumoconiosis: number of deaths, crude and age-adjusted death rates, U.S. residents age 15 and over, 1968–2014. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/eworld/Grouping/Coal_Workers_Pneumoconiosis/93

- 27.Blackley DJ, Halldin CN, Laney AS. Continued increase in the prevalence of coal workers' pneumoconiosis in the United States, 1970–2017. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(9):1220–1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.