Abstract

Background:

Although fatty acids are involved in critical reproductive processes, the relationship between specific fatty acids and fertility is uncertain. We investigated the relationship between preconception plasma fatty acids and pregnancy outcomes.

Methods:

We included 1,228 women attempting pregnancy with one to two previous pregnancy losses from the EAGeR trial (2007–2011). Plasma fatty acids were measured at baseline. We used log-binomial regression to assess associations between fatty acids and pregnancy, pregnancy loss, and live birth, adjusting for age, race, smoking, BMI, physical activity, income, parity, treatment arm, and cholesterol.

Results:

Although total saturated fatty acids (SFAs) were not associated with pregnancy outcomes, 14:0 (myristic acid; relative risk [RR] = 1.10, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.02, 1.19, per 0.1% increase) and 20:0 (arachidic acid; RR = 1.05, 95% CI = 1.01, 1.08, per 0.1% increase) were positively associated with live birth. Findings suggested a positive association between total monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) and pregnancy and live birth and an inverse association with loss. Total polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) were associated with lower probability of pregnancy (RR = 0.97, 95% CI = 0.95, 1.00) and live birth (RR = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.94, 0.99), and increased risk of loss (RR = 1.10, 95% CI = 1.00, 1.20), per 1% increase. Trans fatty acids and n-3 fatty acids were not associated with pregnancy outcomes.

Conclusions:

Preconception total plasma MUFAs were positively associated with pregnancy and live birth. PUFAs were inversely associated with pregnancy outcomes. Specific SFAs were associated with a higher probability of live birth. Our results suggest that fatty acids may influence pregnancy outcomes.

Keywords: Fatty acids, Live birth, Polyunsaturated fatty acids, Pregnancy, Pregnancy loss

Fatty acids serve as substrates and mediators of prostaglandin synthesis and steroidogenesis and, therefore, are crucial to reproductive processes.1 Depending on molecular structure, fatty acids are classified as saturated fatty acids (SFAs), monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs), and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). Abundant data suggest that dietary fatty acid intake may be critical in the early stages of the reproductive process as it may promote ovulation2 and improve embryo quality.3 Additionally, specific types of fatty acids may play different roles in reproductive processes. Increased serum n-6 and n-3 fatty acids or their ratio, as a marker of optimal nutritional and metabolic balances, in women undergoing in vitro fertilization (IVF) have been associated with increased implantation and pregnancy rates,4 whereas intake of trans fatty acids has been associated with an increased risk of ovulatory infertility.5 Overall evidence suggests that different types of fatty acids may be associated with reproductive health through different mechanisms, perhaps by altering the complex reproductive hormonal system6 or increasing oxidative stress.7,8

Because of the potential influence of fatty acids on various reproductive processes, there is interest in the association of dietary fatty acids with fecundability and pregnancy loss. Most studies of pregnancy outcomes utilized dietary records to approximate fatty acid levels which may be prone to error in addressing a potential link between physiologic status of fatty acids and fertility. In addition, few assessed fatty acid levels at the time of conception, when levels would be most likely to affect fecundability and early pregnancy loss. The few studies assessing preconception fatty acids are in women undergoing IVF and have shown that specific fatty acids are important for improving clinical pregnancy and live birth rates, though it is not known whether these fatty acids are important for fecundability in other populations.

Therefore, we investigated associations between preconception plasma fatty acid status and pregnancy outcomes, including pregnancy, pregnancy loss, and live birth among women with prior pregnancy loss, a group that may be particularly amenable to potential lifestyle changes to improve their fertility. As plasma fatty acids may exert their effects through influencing the hormonal milieu6 and obesity is associated with altered hormonal milieu,9 we further stratified the analysis by body mass index (BMI).

METHODS

Study Design

This is a prospective cohort from the Effects of Aspirin in Gestation and Reproduction (EAGeR) trial, 2007–2011.10 We enrolled 1,228 women who were 18–40 years old, had one or two documented prior pregnancy losses, had regular menstrual cycles of 21–42 days, and were attempting pregnancy without the use of fertility treatment. The detailed study protocol is reported elsewhere.10 Briefly, participants were followed for up to six menstrual cycles and throughout pregnancy for those who became pregnant. The institutional review board at each study site and data coordinating center approved the trial protocol. All participants provided written informed consent before enrolling. The trial was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (#NCT00467363).

Plasma Phospholipid Fatty Acids Analysis

Blood specimens were obtained at baseline and stored at −80°C until analysis. Among 1,228 study participants, preconception plasma phospholipid fatty acids were measured among 1,069 women (159 women did not have sufficient quantity of blood samples) using a method previously described.11 For the extraction of phospholipid fatty acids, plasma was diluted in saline and lipids were extracted with a mixture of chloroform:methanol (2:1, volume for volume). The band of phospholipids was harvested for the formation of methyl esters, and the final product was dissolved in heptane and injected onto a capillary Varian CP7420 30-m column with a Hewlett Packard 5890 chromatograph equipped with a HP6890A autosampler and a flame ionization detector. Individual fatty acids were expressed as a percent of total fatty acids. Coefficients of variation (CVs), a measure of batch-to-batch reliability of an assay expressed as the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean levels, of fatty acids range from 2.1% for 16:0 (palmitic acid) and 18:2n6c (linoleic acid) to 47.0% for 22:0 (behenic acid), where an analyte with CV <20% is generally considered a reliable biomarker.

Fatty acids are presented by a shorthand nomenclature which contains the number of carbons and the number of double bonds separated by a colon (e.g., 18:3; 18 carbons and three double bonds). The carbon atom possessing the first double bond from the omega (methyl) end of the fatty acid chain is denoted by n (e.g., n-3) and its cis-trans isomeric configuration is denoted by c or t. We classified 27 individual fatty acids based on common chemical structure and properties and created composite variables of fatty acids, such as total SFA, total MUFA, and total PUFA (eTable 1; http://links.lww.com/EDE/B563). Individual PUFAs were further grouped into n-6 fatty acids, n-3 fatty acids, or marine fatty acids. We also calculated ratios of selected plasma fatty acids, including PUFA:SFA, n-6 fatty acid:n-3 fatty acid, arachidonic acid:eicosapentaenoic acid, and arachidonic acid:marine fatty acids.

Outcome Assessment

The primary outcomes of this analysis included pregnancy, pregnancy loss, and live birth. Outcome assessments have been previously described in detail.12,13 Briefly, pregnancies were determined by positive urine pregnancy tests (Quidel Quickvue, Quidel Corporation), conducted each time participants reported missing menses. Urine human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) testing was performed on daily first-morning urine samples collected on the last 10 days of each woman’s first and second cycles of study participation and on spot urine samples collected at all end-of-cycle visits. Pregnancies were confirmed by ultrasound at 6–7 weeks gestation. Pregnancy loss was defined as an hCG-detected pregnancy that did not last until clinical confirmation, or by detection of a loss by the study participant or her primary care provider after clinical confirmation.13 Live birth was defined as delivering a live infant.

Covariate Assessment

We collected data on participants’ demographic and reproductive characteristics at baseline through questionnaire. These include age, race, smoking, physical activity, income, and parity. Height and weight were measured at baseline to calculate BMI (kg/m2).

Statistical Analysis

We characterized the distribution of demographic and lifestyle factors by tertiles of total PUFAs and SFAs, with Chi-square tests and analysis of variance (ANOVA) used for comparisons. PUFAs and SFAs were evaluated as they have shown associations with cardiovascular disease in previous studies.14–16 We assessed means and standard deviations of plasma phospholipid fatty acids by BMI <25 and ≥25 kg/m2.

Approximately, 13% (n = 159) of women did not have a sufficient quantity of blood samples to determine preconception plasma phospholipid fatty acid status. We used multiple imputation model (PROC MI) with fully conditional specification method to impute missing plasma fatty acids and covariates (e.g., BMI, 1.6%; alcohol, 1.3%; physical activity, 0.1%; income, 0.1%; vitamin use, 1.5%; total cholesterol concentrations, 1.7%) in five imputed data sets, with PROC MIANALYZE to combine the results. We also included age, race, parity, number of cycles attempting pregnancy before study entry, and treatment arm in the imputation model. The imputed data sets were used during the multivariable analysis.

We used log-binomial regression models to examine associations between plasma fatty acids and pregnancy, live birth, and pregnancy loss and estimate relative risks (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Individual and composite variables of plasma fatty acids were evaluated as continuous variables (per 1% change in total plasma fatty acids). For fatty acids with mean levels below 1% of total fatty acids (e.g., SFA 14:0, 15:0, etc.), models were evaluated per 0.1% change, and ratios of fatty acids were assessed per 0.1 change. We included all women in the analyses of pregnancy and live birth to provide interpretation of the association with fatty acids among women planning pregnancy. As the risk of pregnancy loss generally becomes a primary concern during early pregnancy, both biologically and clinically, we restricted our analysis of loss to women with hCG pregnancy. Pregnancy loss models were weighted using inverse probability weights which were created based on factors associated with becoming pregnant.17 Models were adjusted for age, race, BMI, smoking, physical activity, income, parity, total cholesterol concentration, and treatment arm. As associations between plasma fatty acids and pregnancy outcomes may differ by BMI through altered hormonal milieu,9 we stratified the models by BMI (<25 and ≥25 kg/m2) while adjusting for the above covariates, except BMI. Given the hypothesis-generating nature of this analysis, we accounted for multiple comparisons by adjusting all models for the false discovery rate within categories of fatty acids (e.g., total plasma fatty acids [total SFAs, total MUFAs, total PUFAs], odd-chain SFAs, even-chain SFAs, trans fatty acids, MUFAs, n-6 fatty acids, n-3 fatty acids, and ratios).

A sensitivity analysis was conducted for unmeasured confounding to evaluate the impact of a possible unmeasured dietary factor (e.g., fish consumption) on estimates of the association between selected plasma fatty acids and pregnancy outcomes (i.e., total MUFAs and PUFAs with live birth). Specifically, we simulated an unmeasured variable for a range of correlations between fish consumption and plasma fatty acids and fish consumption and live birth. The association between the unmeasured confounder and live birth was set to RRs of 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0, reflecting potential negative associations18,19 and positive associations20 between dietary factors and pregnancy outcomes. We set the correlation between the unmeasured confounder and plasma fatty acids to vary from ρ = 0 to 0.8, based on previous literature which reported correlations between 0.41 to 0.58.21–23 We additionally investigated the impact of excluding plasma fatty acids with CVs >20% from the composite variables on the overall results. CVs were 21.0% for 22:4n-6 (adrenic acid), 25.1% for 20:0 (arachidic acid), 28.8% for 24:0 (lignoceric acid), 42.0% for 24:1n-9 (nervonic acid), and 47.0% for 22:0 (behenic acid). We used SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) for statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Women who were in the lower tertiles of total plasma PUFAs generally had a higher BMI, never consumed alcohol, had a lower income, were not employed at enrollment, and had longer time from last pregnancy loss, compared with the highest tertile of PUFAs (Table 1). Women who were in the lower tertile of total plasma SFAs tended to have a lower BMI, had a higher income, had only one previous live birth, and achieved pregnancy after randomization, compared with the highest tertile of SFAs. In Table 2, the distribution of plasma phospholipid fatty acids is presented by BMI. In general, most measured plasma fatty acids differed only marginally by BMI, with SFAs slightly higher and MUFAs and PUFAs slightly lower in women with BMI ≥25 kg/m2 compared with >25.

TABLE 1.

Demographic Characteristics of 1,069 Study Participants with Available Measures of Preconception Plasma Phospholipid Fatty Acids Measurements by Tertiles of Total Plasma PUFA and SFA Levels in the EAGeR trial

| PUFA | SFA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) or Mean ± SDs | Tertile 1 (n = 356) | Tertile 2 (n = 357) | Tertile 3 (n = 356) | Tertile 1 (n = 356) | Tertile 2 (n = 357) | Tertile 3 (n = 356) |

| % of total fatty acids | 30.2–2.7 | 42.7–14.0 | 44.0–47.1 | 29.6–38.8 | 38.8–39.8 | 39.8–57.2 |

| Age (year, mean ± SD) | 28.7±4.9 | 28.4±4.7 | 29.1 ±4.7 | 28.8±4.5 | 29.0±4.9 | 28.3±5.0 |

| BMI (kg/m2, mean ± SD) | 26.7±6.8 | 26.1±6.5 | 25.4±5.8 | 24.5±5.4 | 25.7±6.4 | 28.0±6.7 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 337 (95) | 337 (94) | 339 (95) | 341 (96) | 339 (95) | 333 (94) |

| Non-White | 19 (5) | 20 (6) | 17 (5) | 15 (4) | 18 (5) | 23 (6) |

| Cigarette smoking | ||||||

| Never | 299 (84) | 311 (88) | 313 (89) | 312 (89) | 317 (89) | 294 (83) |

| Fewer than 6 times per week | 33 (9) | 23 (7) | 24 (7) | 22 (6) | 23 (7) | 35 (10) |

| Daily | 24 (7) | 18 (5) | 14 (4) | 16 (5) | 16 (5) | 24 (7) |

| Alcohol drinking | ||||||

| Never | 239 (68) | 242 (69) | 216 (61) | 243 (69) | 229 (65) | 225 (65) |

| Sometimes | 101 (29) | 100 (29) | 131 (37) | 104 (30) | 113 (32) | 115 (33) |

| Often | 13 (4) | 7 (2) | 5 (1) | 4 (1) | 12 (3) | 9 (3) |

| Physical activity | ||||||

| High | 123 (35) | 117 (33) | 107 (30) | 126 (35) | 108 (30) | 113 (32) |

| Moderate | 139 (39) | 144 (40) | 160 (45) | 143 (40) | 159 (44) | 141 (40) |

| Low | 94 (26) | 96 (27) | 89 (25) | 87 (24) | 90 (25) | 102 (29) |

| Education | ||||||

| >High school | 309 (87) | 312 (87) | 311 (87) | 317 (89) | 308 (86) | 307 (86) |

| High school | 39 (11) | 38 (11) | 40 (11) | 34 (10) | 42 (12) | 41 (12) |

| <High school | 8 (2) | 7 (2) | 5 (1) | 5 (1) | 7 (2) | 8 (2) |

| Income | ||||||

| <$20,000 | 36 (10) | 24 (7) | 15 (4) | 22 (6) | 19 (5) | 34 (10) |

| $20,000–<$40,000 | 93 (26) | 100 (28) | 80 (23) | 79 (22) | 86 (24) | 108 (30) |

| $40,000–<$75,000 | 47 (13) | 45 (13) | 68 (19) | 60 (17) | 51 (14) | 49 (14) |

| $75,000–<$100,000 | 38 (11) | 45 (13) | 54 (15) | 57 (16) | 49 (14) | 31 (9) |

| ≥$100,000 | 141 (40) | 143 (40) | 139 (39) | 137 (39) | 152 (43) | 134 (38) |

| Employment | ||||||

| Yes | 246 (73) | 261 (74) | 274 (80) | 259 (76) | 270 (77) | 252 (74) |

| No | 90 (27) | 90 (26) | 70 (20) | 83 (24) | 80 (23) | 87 (26) |

| Time from last pregnancy loss (month) | ||||||

| ≤4 | 183 (52) | 176 (50) | 199 (57) | 203 (59) | 181 (51) | 174 (49) |

| 5–8 | 57 (16) | 80 (23) | 55 (16) | 55 (16) | 68 (19) | 69 (20) |

| 9–12 | 41 (12) | 19 (5) | 31 (9) | 28 (8) | 29 (8) | 34 (10) |

| >12 | 68 (20) | 75 (21) | 67 (19) | 61 (18) | 74 (21) | 75 (21) |

| Number of pregnancies, not including losses | ||||||

| 0 | 146 (41) | 154 (43) | 156 (44) | 136 (38) | 168 (47) | 152 (43) |

| 1 | 126 (35) | 133 (37) | 120 (34) | 141 (40) | 116 (33) | 122 (34) |

| 2 | 77 (22) | 63 (18) | 75 (21) | 70 (20) | 69 (19) | 76 (21) |

| 3 | 7 (2) | 7 (2) | 5 (1) | 9 (3) | 4 (1) | 6 (2) |

| Number of previous live birth | ||||||

| 0 | 154 (43) | 166 (47) | 171 (48) | 142 (40) | 179 (50) | 170 (48) |

| 1 | 128 (36) | 139 (39) | 125 (35) | 158 (44) | 119 (33) | 115 (32) |

| 2 | 74 (21) | 52 (15) | 60 (17) | 56 (16) | 59 (17) | 71 (20) |

| Number of previous loss | ||||||

| 1 | 231 (65) | 240 (67) | 247 (69) | 242 (68) | 239 (67) | 237 (67) |

| 2 | 125 (35) | 117 (33) | 109 (31) | 114 (32) | 118 (33) | 119 (33) |

| Pregnancy after randomization | ||||||

| Yes | 243 (68) | 221 (62) | 236 (66) | 249 (70) | 236 (66) | 215 (60) |

| No | 113 (32) | 136 (38) | 120 (34) | 107 (30) | 121 (34) | 141 (40) |

SD indicates standard deviation.

TABLE 2.

Distribution of Preconception Plasma Phospholipid Fatty Acids (% of Total Fatty Acids) by Body Mass Index Among 1,069 Women in the EAGeR Trial

| Fatty Acids | Mean (SD) | BMI <25kg/m2 (n = 569) Mean (SD) | BMI ≥25kg/m2 (n = 482) Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SFA, % of total fatty acids | 39.37 (1.52) | 39.12 (1.15) | 39.70 (1.81) |

| 14:0 | 0.284 (0.07) | 0.28 (0.07) | 0.29 (0.07) |

| 15:0 | 0.192 (0.04) | 0.20 (0.04) | 0.19 (0.04) |

| 16:0 | 23.48 (1.26) | 23.51 (1.20) | 23.45 (1.33) |

| 17:0 | 0.378 (0.05) | 0.390 (0.05) | 0.364 (0.05) |

| 18:0 | 13.98 (1.41) | 13.69 (1.09) | 14.35 (1.65) |

| 20:0 | 0.31 (0.13) | 0.31 (0.11) | 0.32 (0.15) |

| 22:0 | 0.30 (0.19) | 0.30 (0.19) | 0.30 (0.20) |

| 24:0 | 0.45 (0.25) | 0.45 (0.24) | 0.44 (0.26) |

| Odd chain | 0.57 (0.08) | 0.59 (0.08) | 0.55 (0.08) |

| Even chain | 38.80 (1.53) | 38.53 (1.16) | 39.15 (1.82) |

| MUFA, % of total fatty acids | 11.51 (1.23) | 11.69 (1.24) | 11.29 (1.17) |

| Trans fatty acids | 0.95 (0.33) | 0.94 (0.33) | 0.96 (0.34) |

| 18:ln-7-9t | 0.71 (0.24) | 0.71 (0.24) | 0.71 (0.24) |

| 18:ln-6t | 0.24 (0.10) | 0.23 (0.10) | 0.25 (0.10) |

| 16:ln-7c | 0.42(0.15) | 0.40(0.15) | 0.45 (0.15) |

| I8:ln-9c | 7.65 (1.00) | 7.82 (1.04) | 7.45 (0.93) |

| 18:ln-7c | 1.21 (0.19) | 1.24 (0.18) | 1.16 (0.18) |

| 18:ln-6c | 0.26 (0.15) | 0.26 (0.16) | 0.25 (0.13) |

| 20:ln-9 | 0.24 (0.06) | 0.25 (0.06) | 0.24 (0.06) |

| 24:ln-9 | 0.79 (0.49) | 0.78 (0.48) | 0.78 (0.49) |

| PUFA, % of total fatty acids | 43.20(1.69) | 43.30(1.56) | 43.06(1.85) |

| n-6 fatty acids | 38.32 (1.97) | 38.28 (1.95) | 38.36 (1.99) |

| 18:2n-6c/c | 22.27 (2.54) | 22.52 (2.49) | 21.96 (2.55) |

| 18:3n-6 | 0.13 (0.07) | 0.12 (0.07) | 0.14 (0.08) |

| 20:2n-6 | 0.44 (0.14) | 0.42 (0.13) | 0.45 (0.16) |

| 20:3n-6 | 3.31 (0.80) | 3.09 (0.70) | 3.56 (0.84) |

| 20:4n-6 | 11.09 (1.71) | 11.05 (1.69) | 11.14 (1.75) |

| 22:4n-6 | 0.54 (0.17) | 0.53 (0.16) | 0.54 (0.18) |

| 22:5n-6 | 0.56 (0.22) | 0.55 (0.21) | 0.57 (0.23) |

| n-3 fatty acids | 4.87 (1.30) | 5.02 (1.45) | 4.71 (1.08) |

| 18:3n-3 | 0.25 (0.07) | 0.25 (0.07) | 0.25 (0.08) |

| Marine fatty acids | 4.63 (1.30) | 4.77 (1.45) | 4.46 (1.08) |

| 20:5n-3 | 0.69 (0.48) | 0.71 (0.58) | 0.68 (0.32) |

| 22:5n-3 | 0.95 (0.20) | 0.96 (0.21) | 0.94 (0.19) |

| 22:6n-3 | 2.99 (0.95) | 3.11 (1.02) | 2.84 (0.85) |

| PUFA: SFA | 1.10 (0.07) | 1.11 (0.06) | 1.09 (0.08) |

| 20:4n-6 (arachidonic acid): 20:5n-3 (eicosapentaenoic acid) | 19.28 (7.36) | 19.64 (7.73) | 18.78 (6.84) |

| 20:4n-6 (arachidonic acid):Marine fatty acids | 2.53 (0.60) | 2.47 (0.64) | 2.60 (0.54) |

| n-6 fatty acids:n-3 fatty acids | 8.35 (2.02) | 8.17 (2.11) | 8.54 (1.90) |

n = 18 for missing BMI and n = 159 for missing fatty acids.

SD indicates standard deviation.

Overall, 797 women became pregnant. Among them, 597 achieved live birth, 188 experienced a pregnancy loss, and 12 withdrew from the study after achieving a pregnancy (no information was available regarding the outcome of these pregnancies). Table 3 presents results for associations between individual and composite fatty acids and pregnancy outcomes (eTable 2; http://links.lww.com/EDE/B563, presents unadjusted results). Overall, we found that higher preconception 14:0 (myristic acid) was associated with a lower probability of pregnancy loss (RR = 0.81, 95% CI = 0.66, 0.99, per 0.1% increase) and higher probability of live birth (RR = 1.10, 95% CI = 1.02, 1.19, per 0.1% increase). Higher 20:0 (arachidic acid) was also associated with a higher probability of live birth (RR = 1.05, 95% CI = 1.01, 1.08, per 0.1% increase). Total SFAs, odd-chain SFAs, and even-chain SFAs were not associated with pregnancy outcomes. Our data suggest that total MUFAs were positively associated with pregnancy (RR = 1.02, 95% CI = 0.99, 1.04) and live birth (RR = 1.03, 95% CI = 1.01, 1.06) and inversely associated with pregnancy loss (RR = 0.91 95% CI = 0.81, 1.02), per 1% increase. We found no associations between trans fatty acids and pregnancy outcomes. Among individual PUFAs, higher 20:2n-6 (eicosadienoic acid) was associated with a higher probability of live birth (RR = 1.04, 95% CI = 1.01, 1.08, per 0.1% increase) and 22:5n-3 (docosapentaenoic acid) with a lower probability of live birth (RR = 0.97, 95% CI = 0.94, 1.00, per 0.1% increase). Total PUFAs were associated with a lower probability of pregnancy (RR = 0.97, 95% CI = 0.95, 1.00) and live birth (RR = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.94, 0.99) and a higher risk of pregnancy loss (RR = 1.10, 95% CI = 1.00, 1.20), per 1% increase. Similar results were detected for total n-6 fatty acids, whereas no associations were observed for total n-3 fatty acids. We also found that a higher PUFA:SFA ratio was associated with a lower probability of live birth (RR = 0.92, 95% CI = 0.85, 0.99, per 0.1 increase in the ratio).

TABLE 3.

Associations Between Preconception Plasma Phospholipid Fatty Acids and Pregnancy, Pregnancy Loss, and Live Birth Among 1,228 Women in the EAGeR Trial

| Pregnancy | Pregnancy Lossa | Live Birth | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR (95% CI) | Adjusted P Valueb | RR (95% CI) | Adjusted P Valueb | RR (95% CI) | Adjusted P Valueb | |

| SFA | 1.01 (0.98, 1.05) | 0.43 | 0.98 (0.89, 1.07) | 0.63 | 1.02 (0.97, 1.07) | 0.41 |

| 14:0c | 1.03 (0.98, 1.09) | 0.56 | 0.81 (0.66,0.99) | 0.30 | 1.10 (1.02, 1.19)d | 0.03 |

| 15:0c | 1.09 (0.99, 1.20) | 0.28 | 0.81 (0.57, 1.15) | 0.36 | 1.14 (1.00, 1.29) | 0.15 |

| 16:0 | 0.99 (0.96, 1.03) | 0.72 | 0.92 (0.82, 1.04) | 0.42 | 1.01 (0.96, 1.06) | 0.91 |

| 17:0c | 1.01 (0.93, 1.10) | 0.80 | 1.23 (0.96, 1.57) | 0.31 | 0.98 (0.88, 1.09) | 0.72 |

| 18:0 | 1.02 (0.98, 1.06) | 0.66 | 1.04 (0.96, 1.12) | 0.60 | 1.00 (0.95, 1.05) | 0.91 |

| 20:0c | 1.02 (1.00, 1.05) | 0.30 | 0.91 (0.81, 1.03) | 0.42 | 1.05 (1.01, 1.08)d | 0.03 |

| 22:0c | 1.02 (1.00, 1.04) | 0.30 | 0.99 (0.92, 1.06) | 0.71 | 1.03 (1.00, 1.06) | 0.20 |

| 24:0c | 1.00 (0.98, 1.01) | 0.72 | 1.02 (0.95, 1.08) | 0.71 | 1.00 (0.97, 1.02) | 0.91 |

| Odd chainc | 1.03 (0.98, 1.09) | 0.34 | 1.04 (0.88, 1.21) | 0.67 | 1.05 (0.97, 1.13) | 0.31 |

| Even chain | 1.01 (0.98, 1.05) | 0.66 | 0.98 (0.89, 1.07) | 0.71 | 1.02 (0.97, 1.07) | 0.80 |

| MUFA | 1.02 (0.99, 1.04) | 0.25 | 0.91 (0.81, 1.02) | 0.16 | 1.03 (1.01, 1.06)d | 0.03 |

| Trans fatty acidsc | 1.00 (0.99, 1.02) | 0.98 | 1.00 (0.96, 1.04) | 0.98 | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) | 0.66 |

| 18:ln-7-9tc | 1.00 (0.99, 1.02) | 0.98 | 1.00 (0.95, 1.05) | 0.98 | 1.01 (0.98, 1.04) | 0.66 |

| 18:ln-6tc | 1.00 (0.95, 1.05) | 0.98 | 1.00 (0.89, 1.13) | 0.98 | 1.01 (0.95, 1.08) | 0.66 |

| 16:ln-7cc | 1.00 (0.98, 1.03) | 1.00 | 0.94 (0.85, 1.04) | 0.57 | 1.00 (0.97, 1.04) | 0.94 |

| 18:ln-9c | 1.02 (0.99, 1.05) | 0.88 | 0.92 (0.78, 1.08) | 0.57 | 1.03 (1.00, 1.07) | 0.38 |

| 18:ln-7c | 1.10 (0.87, 1.40) | 0.88 | 1.32 (0.53,3.34) | 0.61 | 0.95 (0.68, 1.33) | 0.94 |

| 18:ln-6cc | 1.00 (0.97, 1.03) | 1.00 | 0.98 (0.89, 1.07) | 0.61 | 1.01 (0.97, 1.05) | 0.94 |

| 20:ln-9c | 1.02 (0.96, 1.09) | 0.88 | 1.10 (0.85, 1.44) | 0.61 | 1.00 (0.91, 1.11) | 0.94 |

| 24:ln-9c | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | 1.00 | 0.98 (0.95, 1.01) | 0.57 | 1.01 (1.00, 1.02) | 0.44 |

| PUFA | 0.97 (0.95, 1.00) | 0.11 | 1.10 (1.00, 1.20) | 0.16 | 0.96 (0.94, 0.99)d | 0.02 |

| n-6 fatty acids | 0.98 (0.96, 1.00) | 0.66 | 1.08 (1.01, 1.17) | 0.28 | 0.97 (0.94, 0.99) | 0.06 |

| 18:2n-6c/c | 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) | 0.99 | 1.03 (0.98, 1.08) | 0.43 | 0.98 (0.96, 1.00) | 0.21 |

| 18:3n-6c | 1.00 (0.94, 1.06) | 0.99 | 0.83 (0.64, 1.07) | 0.40 | 1.05 (0.97, 1.14) | 0.39 |

| 20:2n-6c | 1.00 (0.97, 1.04) | 0.99 | 0.92 (0.82, 1.02) | 0.40 | 1.04 (1.01, 1.08) | 0.10 |

| 20:3n-6 | 1.00 (0.95, 1.07) | 0.99 | 0.99 (0.81, 1.22) | 0.95 | 1.00 (0.91, 1.10) | 0.98 |

| 20:4n-6 | 1.00 (0.97, 1.02) | 0.99 | 1.03 (0.95, 1.13) | 0.58 | 1.00 (0.96, 1.03) | 0.90 |

| 22:4n-6c | 0.99 (0.97, 1.02) | 0.99 | 1.04 (0.97, 1.12) | 0.43 | 0.99 (0.96, 1.02) | 0.76 |

| 22:5n-6c | 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) | 0.66 | 1.01 (0.95, 1.07) | 0.95 | 0.99 (0.96, 1.01) | 0.50 |

| n-3 fatty acids | 1.00 (0.96, 1.03) | 0.78 | 0.96 (0.85, 1.08) | 0.62 | 0.99 (0.95, 1.04) | 0.81 |

| 18:3n-3c | 1.01 (0.95, 1.07) | 0.78 | 1.19 (0.97, 1.46) | 0.60 | 0.99 (0.91, 1.07) | 0.81 |

| Marine fatty acids | 1.00 (0.96, 1.03) | 0.78 | 0.95 (0.85, 1.07) | 0.62 | 1.00 (0.95, 1.04) | 0.81 |

| 20:5n-3c | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | 0.78 | 0.98 (0.94, 1.02) | 0.62 | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | 0.81 |

| 22:5n-3c | 0.98 (0.96, 1.00) | 0.43 | 1.00 (0.93, 1.08) | 0.95 | 0.97 (0.94, 1.00) | 0.18 |

| 22:6n-3 | 1.01 (0.96, 1.06) | 0.78 | 1.01 (0.95, 1.07) | 0.62 | 1.01 (0.95, 1.07) | 0.81 |

| PUFA:SFAe | 0.95 (0.89, 1.01) | 0.34 | 1.18 (0.94, 1.48) | 0.31 | 0.92 (0.85, 0.99) | 0.13 |

| 20:4n-6 (arachidonic acid): 20:5n-3 (eicosapentaenoic acid)e | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.90 | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.43 | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.59 |

| 20:4n-6 (arachidonic acid):Marine fatty acidse | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | 0.90 | 1.02 (1.00, 1.05) | 0.60 | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | 0.60 |

| n-6 fatty acids:n-3 fatty acidse | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.90 | 1.01 (1.00, 1.01) | 0.31 | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.59 |

Imputed data for missing fatty acid measurements (n = 159) and covariates were used. Models were adjusted for age, body mass index, cigarette smoking, physical activity, income, parity, total cholesterol concentration, and treatment group.

Weighted log-binomial regression models were used.

Adjusted for false discovery rate within categories of fatty acids (e.g., total fatty acids [total SFAs, total MUFAs, total PUFAs], odd-chain SFAs, even-chain SFAs, trans fatty acids, MUFAs, n-6 fatty acids, n-3 fatty acids, ratios).

Results are shown for an increase in 0.1% of total fatty acids.

Associations remained significant after adjustment for the false discovery rate within categories of fatty acids.

Results are shown for an increase in 0.1 for ratios.

When results were stratified by BMI, we observed no associations between total SFAs and pregnancy, pregnancy loss, and live birth (Table 4). Although we found positive associations between a few individual SFAs and live birth among both women with BMI <25 kg/m2 and ≥25 kg/m2, effect estimates had large confidence intervals. Our data showed no associations between MUFAs or trans fatty acids and pregnancy outcomes by BMI status. However, higher total PUFAs were associated with a 13% higher risk of pregnancy loss (RR = 1.13, 95% CI = 1.01, 1.27, per 1% increase) and 4% lower probability of live birth (RR = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.93, 0.99, per 1% increase) among women with BMI <25 kg/m2. Similar results were found for n-6 fatty acids and pregnancy loss and live birth among women with BMI <25 kg/m2.

TABLE 4.

Associations Between Fatty Acids and Pregnancy, Pregnancy Loss, and Live Birth by Body Mass Index (n = 1,228)

| Pregnancy | Pregnancy Lossa | Live Birth | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI <25kg/m2 (n = 644) RR (95% CI) | BMI ≥25 kg/m2 (n = 584) RR (95% CI) | BMI <25kg/m2 (n = 644) RR (95% CI) | BMI ≥25 kg/m2 (n = 584) RR (95% CI) | BMI <25 kg/m2 (n = 644) RR (95% CI) | BMI ≥25 kg/m2 (n = 584) RR (95% CI) | |

| SFA | 1.01 (0.97, 1.04) | 1.01 (0.96, 1.05) | 0.97 (0.85, 1.11) | 1.01 (0.90, 1.13) | 1.05 (0.97, 1.13) | 1.01 (0.94, 1.08) |

| 14:0b | 1.01 (0.96, 1.06) | 1.07 (0.97, 1.17) | 0.92 (0.70, 1.20) | 0.74 (0.53, 1.03) | 1.09 (0.98, 1.21) | 1.17 (1.02, 1.34) |

| 15:0b | 1.05 (0.95, 1.15) | 1.08 (0.96, 1.21) | 0.88 (0.53, 1.44) | 0.64 (0.31, 1.32) | 1.24 (1.01, 1.51) | 1.08 (0.97, 1.20) |

| 16:0 | 1.00 (0.97, 1.03) | 0.98 (0.93, 1.03) | 1.02 (0.88, 1.19) | 0.82 (0.67, 1.00) | 1.01 (0.94, 1.08) | 1.02 (0.94, 1.10) |

| 17:0b | 0.99 (0.93, 1.06) | 1.09 (0.97, 1.21) | 1.04 (0.73, 1.49) | 1.28 (0.89, 1.84) | 0.97 (0.84, 1.11) | 1.06 (0.91, 1.24) |

| 18:0 | 1.00 (0.97, 1.04) | 1.01 (0.97, 1.06) | 0.98 (0.82, 1.16) | 1.07 (1.00, 1.15) | 1.01 (0.93, 1.08) | 0.98 (0.92, 1.06) |

| 20:0b | 1.02 (0.99, 1.05) | 1.00 (0.95, 1.05) | 0.88 (0.74, 1.05) | 0.98 (0.82, 1.16) | 1.06 (1.01, 1.13) | 1.01 (0.94, 1.08) |

| 22:0b | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) | 1.02 (0.99, 1.05) | 0.96 (0.87, 1.07) | 1.03 (0.95, 1.12) | 1.04 (1.00, 1.08) | 1.02 (0.97, 1.07) |

| 24:0b | 1.00 (0.98, 1.01) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.03) | 1.00 (0.91, 1.09) | 1.05 (0.96, 1.16) | 1.00 (0.97, 1.04) | 1.00 (0.96, 1.04) |

| Odd chainb | 1.01 (0.97, 1.05) | 1.08 (1.00, 1.17) | 0.99 (0.78, 1.24) | 1.03 (0.78, 1.37) | 1.03 (0.94, 1.13) | 1.12 (1.01, 1.24) |

| Even chain | 1.01 (0.97, 1.04) | 1.00 (0.96, 1.05) | 0.97 (0.85, 1.11) | 1.01 (0.90, 1.12) | 1.04 (0.97, 1.13) | 1.01 (0.94, 1.08) |

| MUFA | 1.02 (0.99, 1.05) | 1.02 (0.97, 1.08) | 0.91 (0.78, 1.06) | 0.95 (0.79, 1.13) | 1.03 (1.00, 1.07) | 1.05 (0.97, 1.13) |

| Trans fatty acidsb | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) | 0.99 (0.94, 1.04) | 1.00 (0.95, 1.05) | 1.00 (0.97, 1.02) | 1.01 (0.98, 1.05) |

| 18:ln-7-9tb | 1.00 (0.98, 1.01) | 1.01 (0.98, 1.05) | 0.98 (0.91, 1.05) | 1.00 (0.93, 1.07) | 1.00 (0.96, 1.03) | 1.02 (0.97, 1.07) |

| 18:ln-6tb | 1.00 (0.96, 1.03) | 1.01 (0.93, 1.10) | 0.95 (0.80, 1.14) | 1.02 (0.86, 1.20) | 0.99 (0.91, 1.07) | 1.03 (0.91, 1.16) |

| 16:ln-7cb | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) | 0.98 (0.93, 1.04) | 1.04 (0.92, 1.19) | 0.87 (0.73, 1.03) | 0.99 (0.95, 1.04) | 1.01 (0.93, 1.08) |

| 18:ln-9c | 1.02 (0.99, 1.06) | 1.04 (0.97, 1.12) | 0.94 (0.77, 1.14) | 0.94 (0.73, 1.21) | 1.04 (1.00, 1.08) | 1.06 (0.94, 1.19) |

| 18:ln-7c | 1.02 (0.85, 1.23) | 1.11 (0.77, 1.61) | 1.49 (0.50,4.44) | 1.08 (0.20,5.94) | 0.88 (0.58, 1.34) | 0.99 (0.59, 1.67) |

| 18:ln-6cb | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) | 0.98 (0.91, 1.04) | 0.97 (0.85, 1.10) | 0.99 (0.85, 1.17) | 1.01 (0.96, 1.05) | 1.01 (0.94, 1.08) |

| 20:ln-9b | 0.99 (0.94, 1.05) | 1.14 (1.01, 1.29) | 1.22 (0.81, 1.83) | 1.01 (0.69, 1.49) | 0.94 (0.81, 1.08) | 1.18 (0.99, 1.40) |

| 24:ln-9b | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.01) | 0.97 (0.93, 1.01) | 1.00 (0.96, 1.04) | 1.02 (1.00, 1.03) | 1.00 (0.97, 1.02) |

| PUFA | 0.98 (0.96, 1.01) | 0.99 (0.94, 1.03) | 1.13 (1.01, 1.27) | 1.02 (0.89, 1.16) | 0.96 (0.93, 0.99) | 0.97 (0.92, 1.02) |

| n-6 fatty acids | 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) | 0.98 (0.94, 1.03) | 1.12 (1.02, 1.23) | 1.02 (0.90, 1.15) | 0.96 (0.93, 0.99)c | 0.97(0.92, 1.03) |

| 18:2n-6c/c | 1.00 (0.98, 1.01) | 0.98 (0.95, 1.01) | 1.06 (0.99, 1.13) | 0.97 (0.89, 1.05) | 0.98 (0.95, 1.01) | 0.98 (0.94, 1.02) |

| 18:3n-6b | 0.99 (0.95, 1.04) | 1.00 (0.90, 1.10) | 0.85 (0.63, 1.16) | 0.81 (0.57, 1.14) | 1.03 (0.93, 1.13) | 1.06 (0.94, 1.20) |

| 20:2n-6b | 1.00 (0.98, 1.03) | 1.00 (0.96, 1.05) | 0.84 (0.72, 0.99) | 0.96 (0.83, 1.11) | 1.06 (1.01, 1.11) | 1.01 (0.95, 1.07) |

| 20:3n-6 | 1.01 (0.96, 1.05) | 0.95 (0.85, 1.06) | 1.03 (0.79, 1.36) | 0.98 (0.77, 1.23) | 1.03 (0.93, 1.14) | 0.93 (0.80, 1.09) |

| 20:4n-6 | 0.99 (0.98, 1.01) | 1.03 (1.00, 1.07) | 1.03 (0.92, 1.15) | 1.07 (0.94, 1.22) | 0.98 (0.93, 1.03) | 1.02 (0.97, 1.08) |

| 22:4n-6b | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) | 0.98 (0.93, 1.03) | 0.94 (0.83, 1.06) | 1.12 (1.01, 1.25) | 1.02 (0.97, 1.07) | 0.95 (0.89, 1.01) |

| 22:5n-6b | 0.99 (0.98, 1.01) | 0.99 (0.96, 1.03) | 0.99 (0.91, 1.09) | 1.03 (0.94, 1.12) | 0.99 (0.95, 1.02) | 0.99 (0.95, 1.04) |

| n-3 fatty acids | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) | 1.01 (0.94, 1.09) | 0.95 (0.82, 1.10) | 0.97 (0.78, 1.21) | 1.00 (0.95, 1.04) | 1.00 (0.92, 1.10) |

| 18:3n-3b | 1.01 (0.97, 1.05) | 1.03 (0.93, 1.14) | 1.02 (0.78, 1.34) | 1.37 (1.00, 1.89) | 1.02 (0.92, 1.14) | 0.96 (0.84, 1.09) |

| Marine fatty acids | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) | 1.01 (0.94, 1.09) | 0.95 (0.82, 1.10) | 0.95 (0.77, 1.18) | 0.99 (0.95, 1.04) | 1.00 (0.92, 1.10) |

| 20:5n-3b | 1.00 (0.99, 1.00) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) | 0.98 (0.93, 1.03) | 0.98 (0.89, 1.08) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.01) | 1.01 (0.98, 1.04) |

| 22:5n-3b | 0.99 (0.98, 1.01) | 1.00 (0.96, 1.04) | 0.95 (0.88, 1.04) | 1.09 (0.98, 1.21) | 0.97 (0.93, 1.01) | 0.96 (0.91, 1.02) |

| 22:6n-3 | 1.01 (0.98, 1.05) | 1.01 (0.92, 1.10) | 1.01 (0.90, 1.12) | 1.01 (0.90, 1.12) | 1.01 (0.95, 1.07) | 1.01 (0.90, 1.12) |

| PUFA:SFAd | 0.96 (0.90, 1.03) | 0.98 (0.88, 1.10) | 1.26 (0.94, 1.67) | 1.00 (0.74, 1.36) | 0.88 (0.79, 0.99) | 0.95 (0.82, 1.10) |

| 20:4n-6 (arachidonic acid): 20:5n-3 (eicosapentaenoic acid)d | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) |

| 20:4n-6 (arachidonic acid):Marine fatty acidsd | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.02) | 1.02 (0.99, 1.05) | 1.04 (0.98, 1.09) | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) |

| n-6 fatty acids:n-3 fatty acidsd | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 1.00 (0.99, 1.00) | 1.01 (1.00, 1.01) | 1.00 (0.99, 1.02) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 1.00 (0.99, 1.00) |

Imputed data for missing fatty acid measurements (n = 159) and covariates were used. Models were adjusted for age, cigarette smoking, physical activity, income, parity, total cholesterol concentration, and treatment group.

Weighted log-binomial regression models were used.

Results are shown for an increase in 0.1% of total fatty acids.

Associations remained significant after adjustment for the false discovery rate within categories of fatty acids (e.g., total fatty acids [total SFAs, total MUFAs, total PUFAs], odd-chain SFAs, even-chain SFAs, trans fatty acids, MUFAs, n-6 fatty acids, n-3 fatty acids, ratios).

Results are shown for an increase in 0.1 for ratios.

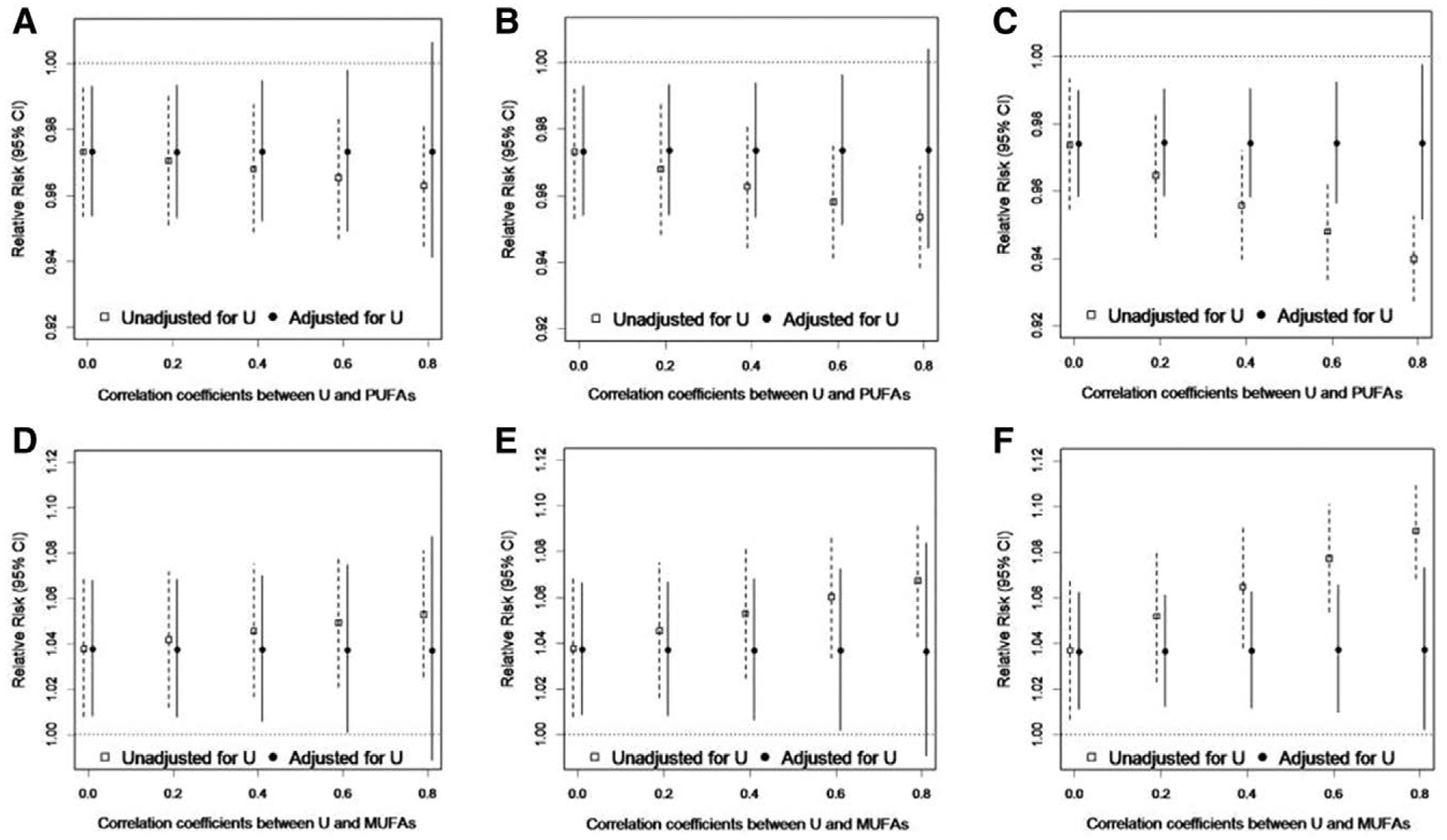

The results of the sensitivity analysis to evaluate the potential impact of unmeasured dietary factors or environmental contaminants from fish consumption on the associations between total PUFAs or total MUFAs and live birth are presented in the Figure. We found that adjustment for unmeasured confounding factors with several different effect estimates with live birth (β from −0.7 to 0.7, corresponding to RRs of 0.5–2.0) and correlations with fatty acids (ρ = 0 to ρ = 0.8) did not produce importantly different results from the models unadjusted for unmeasured confounding factors.

FIGURE.

Results of sensitivity analysis for unmeasured confounding (U) of the total plasma PUFAs-live birth and total plasma MUFAs-live birth associations by fish consumption, EAGeR Trial, 2007–2011. Simulations are data driven with the association between the unmeasured dietary factor and live birth set to be: (A and D) β = −0.7 (RR = 0.5); (B and E) β = 0 (RR = 1.0); (C and F) β = 0.7 (RR = 2.0), across a range of correlations between the unmeasured dietary factor and fatty acids from ρ = 0 to ρ = 0.8.

Excluding the five plasma fatty acids with CVs >20% from the composite measures of SFA, MUFA, and PUFA did not alter the results for pregnancy, pregnancy loss, and live birth.

DISCUSSION

We found that certain preconception plasma phospholipid fatty acids were associated with live birth among women who had experienced one or two previous pregnancy losses. Particularly, higher preconception 14:0 (myristic acid) and 20:0 (arachidic acid) SFAs and total MUFAs were associated with a higher probability of live birth. On the other hand, total PUFAs had an inverse association with both pregnancy and live birth. No associations were found for overall n-3 fatty acids. These results, though perhaps unexpected, collectively suggest the importance of plasma phospholipid fatty acid profile in relation to pregnancy outcomes.

Total SFAs measured in plasma phospholipids were not associated with pregnancy, pregnancy loss, and live birth in our study. These results are in line with null findings for dietary SFA intakes and various reproductive outcomes, including reproductive hormones, anovulation,6 ovulatory infertility,5 and uterine leiomyomata.24 However, our findings on positive associations between specific individual SFAs, including 14:0 (myristic acid) and 20:0 (arachidic acid) fatty acids, and live birth are unexpected. In a large prospective case-cohort study in eight European countries, differential associations between individual SFAs determined in plasma phospholipids and the risk of type 2 diabetes were reported, suggesting differential associations with metabolic risk.25 While there is limited literature to which we can compare our results, our findings for individual SFAs may be related to a differential role of plasma fatty acids on reproductive outcomes.

Given the nutritional value of MUFAs and PUFAs and a suggested beneficial role of these fatty acids in diverse health outcomes, particularly with PUFAs in reproductive processes, our results showing a lower probability of pregnancy and live birth with higher total PUFA levels were unexpected. Our observations might be explained by the biochemical characteristics of plasma PUFAs. Specifically, excessive dietary intake of PUFAs has been shown to increase overall oxidative stress via provision of substrate for lipid peroxidation.7,26 Alternatively, high levels of plasma PUFAs might simply be a marker for the presence of other components of diet that are associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. For instance, the association we observed could have resulted from concurrent exposure to environmental contaminants or heavy metals via ingestion of food items with high fat,27–29 as they can adversely be related to human reproduction. As plasma phospholipid fatty acid status is not entirely due to dietary intake, it is possible that our observations could have been in part due to confounding by complex metabolic pathways that lead to altered fatty acid metabolism and subsequently affect pregnancy outcomes. Our sensitivity analysis for unmeasured confounding, however, indicated that our observed results are not likely due to a single, strong, unmeasured confounder.

The relation of total plasma PUFA concentrations to pregnancy outcomes in our study seems to be largely driven by total n-6 fatty acid concentrations, although we did not find associations for individual n-6 fatty acids (e.g., 18:2n-6c/c [linoleic acid] and 20:4n-6 [arachidonic acid]). These fatty acids are known for their proinflammatory properties30 and for mediating cell inflammation.31 Therefore, our results may reflect the vulnerability of PUFAs, and n-6 fatty acids in particular, to lipid peroxidation and the proinflammatory role of the corresponding peroxidation products, which could possibly increase oxidative stress,8 alter lipid metabolism, disturb reproductive hormones,32 and subsequently affect fertility. Future investigations may consider the role of preconception n-6 fatty acids on pregnancy outcomes in conjunction with a panel of oxidative stress markers. A simultaneous assessment may enable us to better understand the underlying biological mechanisms linking fatty acids and oxidative stress and their potential impact on pregnancy outcomes.

N-3 fatty acids have been of great interest in relation to pregnancy outcomes due to their antioxidative effects and easy accessibility via food items, such as fish, fish oil, and seafood. Although total n-3 fatty acid levels and the individual n-3 fatty acids, including 20:5n-3 (eicosapentaenoic acid) and 22:6n-3 (docosahexaenoic acid), were not associated with pregnancy and live birth, 22:5n-3 (docosapentaenoic acid) was associated with a lower probability of live birth in our study. In rats, high intakes of dietary 20:5n-3 (eicosapentaenoic acid) and 22:6n-3 (docosahexaenoic acid) suppressed lipid peroxidation in the liver, kidney, and testis tissues whereas no such effect was observed for 18:3n-3 (α-linolenic acid), another n-3 fatty acid.33 22:5n-3 (docosapentaenoic acid) was not assessed in that study, thus direct comparison with our result is not possible. However, our observation could be in part due to the differential antioxidative effect of each fatty acid depending on the number of carbons and location of double bonds in its structure, differential misclassification of exposure (e.g., circulating levels versus levels at target tissues), correlations with other dietary factors, or the accumulation of 22:5n-3 (docosapentaenoic acid) which possibly reflects an inability to synthesize 22:6n-3 (docosahexaenoic acid).

There are several limitations in our study. Although plasma fatty acid status reflects dietary fatty acid intake to some extent, the total amount of fat and specific types of dietary fat intake (e.g., fish, seafood, flax oil) could potentially modify overall plasma fatty acid composition.34–37 Due to the lack of dietary and supplement intake data in our study, we were unable to determine the extent to which plasma fatty acid levels were influenced by diet or supplements (e.g., n-3 fatty acid supplement) and whether interventions designed to modify plasma fatty acids would have beneficial effects on pregnancy and pregnancy outcomes. The majority of blood specimens collected preconception were nonfasting in our study population (14.5% of women were fasting at the time of blood sample collection). Although the half-life of n-3 fatty acids is generally longer than a standard fasting period as it ranges from 1.6 to 2.3 days in plasma phospholipids,38 there is a possibility that the half-lives of other individual fatty acids vary and are subsequently reflected in our measurement by increased variability. Common dietary sources of PUFAs, particularly n-3 fatty acids, include fish and seafood, which can also be sources of environmental contaminant exposures. Due to the lack of dietary and environmental assessment in our study, we performed sensitivity analyses which suggested that our results were unlikely to be influenced by a single, unmeasured confounder. Our fatty acid assay focused on the phospholipid fraction of plasma lipids and does not consider the contribution of fatty acid levels in triglycerides or cholesteryl esters. Five fatty acids had reported CVs >20%, and thus their measurements may not be reliable. However, their impact on composite fatty acids was negligible as their levels were very low (Table 2) and the subanalysis excluding those five fatty acids did not alter results. It should be noted that this is an exploratory analysis in which we evaluated a large panel of fatty acids for their associations with pregnancy outcomes given the lack of similar data in this area though results were adjusted for multiple comparisons.

There are also several strengths in our study. The use of preconception fatty acids determined in plasma phospholipids among women who were attempting pregnancy enabled us to address a potential link between physiologic status of specific fatty acids and both pregnancy and pregnancy outcomes. Plasma measurements are less susceptible to error compared with dietary fatty acid assessment, although direct translation of our results to dietary fatty acids is not possible. Our women may be more representative of the general population than women undergoing IVF; however, our results should be interpreted within the confines of the study population. Specifically, all women in our study had experienced one or two previous pregnancy losses, though this is reflective of a significant proportion of reproductive age women.

In conclusion, we observed associations between preconception plasma phospholipid MUFAs and increased probability of pregnancy and live birth. We also found that total PUFAs were inversely associated with pregnancy outcomes. Although total SFAs, trans fatty acids, and n-3 fatty acids were not associated with pregnancy outcomes, the specific SFAs including 14:0 (myristic acid) and 20:0 (arachidic acid) SFAs were associated with improved live birth outcomes. As our results are not likely explained by unmeasured potential confounders, such as dietary factors or environmental contamination through fish consumption, our results suggest that preconception fatty acid status may be associated with pregnancy outcomes, particularly live birth. The potential for preconception fatty acids to influence other pregnancy outcomes deserves further exploration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health (Contract numbers HHSN267200603423, HHSN267200603424, and HHSN267200603426). D.L.K. and U.R.O. have been funded by the NIH Medical Research Scholars Program, a public-private partnership jointly supported by the NIH and generous contributions to the Foundation for the NIH by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation (Grant #2014194), the American Association for Dental Research, the Colgate Palmolive Company, Genentech, and other private donors. For a complete list, visit the foundation website at http://www.fnih.org.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Please see http://grants.nih.gov/grants/policy/data_sharing/ for National Institutes of Health data sharing policy.

Supplemental digital content is available through direct URL citations in the HTML and PDF versions of this article (www.epidem.com).

REFERENCES

- 1.Wathes DC, Abayasekara DR, Aitken RJ. Polyunsaturated fatty acids in male and female reproduction. Biol Reprod. 2007;77:190–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Broughton KS, Bayes J, Culver B. High α-linolenic acid and fish oil ingestion promotes ovulation to the same extent in rats. Nutr Res. 2010;30:731–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hammiche F, Vujkovic M, Wijburg W, et al. Increased preconception omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid intake improves embryo morphology. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:1820–1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jungheim ES, Frolova AI, Jiang H, Riley JK. Relationship between serum polyunsaturated fatty acids and pregnancy in women undergoing in vitro fertilization. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:E1364–E1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chavarro JE, Rich-Edwards JW, Rosner BA, Willett WC. Dietary fatty acid intakes and the risk of ovulatory infertility. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:231–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mumford SL, Chavarro JE, Zhang C, et al. Dietary fat intake and reproductive hormone concentrations and ovulation in regularly menstruating women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103:868–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kang MJ, Shin MS, Park JN, Lee SS. The effects of polyunsaturated:saturated fatty acids ratios and peroxidisability index values of dietary fats on serum lipid profiles and hepatic enzyme activities in rats. Br J Nutr. 2005;94:526–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Gubory KH, Fowler PA, Garrel C. The roles of cellular reactive oxygen species, oxidative stress and antioxidants in pregnancy outcomes. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42:1634–1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sivalingam VN, Myers J, Nicholas S, Balen AH, Crosbie EJ. Metformin in reproductive health, pregnancy and gynaecological cancer: established and emerging indications. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20:853–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schisterman EF, Silver RM, Perkins NJ, et al. A randomised trial to evaluate the effects of low-dose aspirin in gestation and reproduction: design and baseline characteristics. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2013;27: 598–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao J, Schwichtenberg KA, Hanson NQ, Tsai MY. Incorporation and clearance of omega-3 fatty acids in erythrocyte membranes and plasma phospholipids. Clin Chem. 2006;52:2265–2272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schisterman EF, Silver RM, Lesher LL, et al. Preconception low-dose aspirin and pregnancy outcomes: results from the EAGeR randomised trial. Lancet. 2014;384:29–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mumford SL, Silver RM, Sjaarda LA, et al. Expanded findings from a randomized controlled trial of preconception low-dose aspirin and pregnancy loss. Hum Reprod. 2016;31:657–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jakobsen MU, Overvad K, Dyerberg J, Schroll M, Heitmann BL. Dietary fat and risk of coronary heart disease: possible effect modification by gender and age. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:141–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jakobsen MU, O’Reilly EJ, Heitmann BL, et al. Major types of dietary fat and risk of coronary heart disease: a pooled analysis of 11 cohort studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:1425–1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Lorgeril M, Salen P. New insights into the health effects of dietary saturated and omega-6 and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. BMC Med. 2012;10:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cole SR, Hernán MA. Constructing inverse probability weights for marginal structural models. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168:656–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olsen SF, Secher NJ, Tabor A, Weber T, Walker JJ, Gluud C. Randomised clinical trials of fish oil supplementation in high risk pregnancies. Fish Oil Trials In Pregnancy (FOTIP) Team. BJOG. 2000;107:382–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olsen SF, Secher NJ. Low consumption of seafood in early pregnancy as a risk factor for preterm delivery: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2002;324:447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choy CM, Lam CW, Cheung LT, Briton-Jones CM, Cheung LP, Haines CJ. Infertility, blood mercury concentrations and dietary seafood consumption: a case-control study. BJOG. 2002;109:1121–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andersen LF, Solvoll K, Drevon CA. Very-long-chain n-3 fatty acids as biomarkers for intake of fish and n-3 fatty acid concentrates. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;64:305–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hjartåker A, Lund E, Bjerve KS. Serum phospholipid fatty acid composition and habitual intake of marine foods registered by a semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1997;51:736–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Philibert A, Vanier C, Abdelouahab N, Chan HM, Mergler D. Fish intake and serum fatty acid profiles from freshwater fish. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:1299–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wise LA, Radin RG, Kumanyika SK, Ruiz-Narváez EA, Palmer JR, Rosenberg L. Prospective study of dietary fat and risk of uterine leiomyomata. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99:1105–1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Imamura F, Sharp SJ, Koulman A, et al. A combination of plasma phospholipid fatty acids and its association with incidence of type 2 diabetes: the EPIC-InterAct case-cohort study. PLoS Med. 2017;14:e1002409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu ML, Frankel EN, Leibovitz BE, Tappel AL. Effect of dietary lipids and vitamin E on in vitro lipid peroxidation in rat liver and kidney homogenates. J Nutr. 1989;119:1574–1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Persky V, Turyk M, Anderson HA, et al. ; Great Lakes Consortium. The effects of PCB exposure and fish consumption on endogenous hormones. Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109:1275–1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Björnberg KA, Vahter M, Grawé KP, Berglund M. Methyl mercury exposure in Swedish women with high fish consumption. Sci Total Environ. 2005;341:45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Langer P, Kocan A, Tajtaková M, et al. Fish from industrially polluted freshwater as the main source of organochlorinated pollutants and increased frequency of thyroid disorders and dysglycemia. Chemosphere. 2007;67:S379–S385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patterson E, Wall R, Fitzgerald GF, Ross RP, Stanton C. Health implications of high dietary omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids. J Nutr Metab. 2012;2012:539426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Young VM, Toborek M, Yang F, McClain CJ, Hennig B. Effect of linoleic acid on endothelial cell inflammatory mediators. Metabolism. 1998;47:566–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schisterman EF, Gaskins AJ, Mumford SL, et al. ; BioCycle Study Group. Influence of endogenous reproductive hormones on F2-isoprostane levels in premenopausal women: the bioCycle Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172:430–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saito M, Kubo K. Relationship between tissue lipid peroxidation and peroxidizability index after alpha-linolenic, eicosapentaenoic, or docosahexaenoic acid intake in rats. Br J Nutr. 2003;89:19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schaefer EJ, Lamon-Fava S, Spiegelman D, et al. Changes in plasma lipoprotein concentrations and composition in response to a low-fat, high-fiber diet are associated with changes in serum estrogen concentrations in premenopausal women. Metabolism. 1995;44:749–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kasim-Karakas SE, Almario RU, Mueller WM, Peerson J. Changes in plasma lipoproteins during low-fat, high-carbohydrate diets: effects of energy intake. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71:1439–1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raatz SK, Bibus D, Thomas W, Kris-Etherton P. Total fat intake modifies plasma fatty acid composition in humans. J Nutr. 2001;131:231–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arab L Biomarkers of fat and fatty acid intake. J Nutr. 2003;133(suppl 3):925s–932s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zuijdgeest-van Leeuwen SD, Dagnelie PC, Rietveld T, van den Berg JW, Wilson JH. Incorporation and washout of orally administered n-3 fatty acid ethyl esters in different plasma lipid fractions. Br J Nutr. 1999;82:481–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.