Abstract

Background:

Venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) is increasingly used as a life-saving therapy for patients with cardiovascular collapse, but identifying patients unlikely to benefit remains a challenge.

Methods and Results:

We created the RESCUE registry, a retrospective, observational registry of adult patients treated with VA-ECMO between January 2007 and June 2017 at 3 high-volume centers (Columbia University, Duke University, and Washington University) to describe short-term patient outcomes. In 723 patients treated with VA-ECMO, the most common indications for deployment were postcardiotomy shock (31%), cardiomyopathy (including acute heart failure) (26%), and myocardial infarction (17%). Patients frequently suffered in-hospital complications, including acute renal dysfunction (45%), major bleeding (41%), and infection (33%). Only 40% of patients (n = 290) survived to discharge, with a minority receiving durable cardiac support (left ventricular assist device [n = 48] or heart transplantation [n = 7]). Multivariable regression analysis identified risk factors for mortality on ECMO as older age (odds ratio [OR], 1.26; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.12–1.42) and female sex (OR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.02–2.02) and risk factors for mortality after decannulation as higher body mass index (OR 1.17; 95% CI, 1.01-1.35) and major bleeding while on ECMO support (OR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.23–2.99).

Conclusions:

Despite contemporary care at high-volume centers, patients treated with VA-ECMO continue to have significant in-hospital morbidity and mortality. The optimization of outcomes will require refinements in patient selection and improvement of care delivery.

Keywords: Cardiogenic shock, venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, mechanical circulatory support

Mechanical circulatory support (MCS) devices are being increasingly used in the management of circulatory failure, growing 15-fold between 2007 and 2011.1 For cardiogenic shock specifically, MCS was used in approximately 23% of cases in 20142 and 34% of cases in 2019.3 The use of venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO), in particular, has quadrupled in the last decade.4

VA-ECMO uniquely provides rapid biventricular and respiratory support and can be used for circulatory failure for a variety of conditions, including acute heart failure, myocardial infarction, refractory ventricular arrhythmias, postcardiotomy circulatory collapse, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, acute drug toxicity, and viral myocarditis (including recently reported use in novel coronavirus disease-2019).5,6 Recent changes to the United Network for Organ Sharing donor allocation system give ultimate priority to patients treated with ECMO, and these changes have already resulted in its increased use for this purpose.7,8 However, ECMO use is associated with substantial complications, including decreased mobility, continued need for intensive monitoring, vascular complications, and risk of infection. Importantly, patients requiring treatment with this level of support have an estimated survival to hospital discharge of only approximately 40%.4 As ECMO is increasingly used, it will be important to determine which patients are most likely to tolerate this therapy and which patients are at greatest risk of complications. Thus, we created the Registry for Cardiogenic Shock: Utility and Efficacy of Device Therapy (RESCUE), a contemporary registry of patients treated with ECMO at 3 large quaternary care centers with expertise in ECMO, durable MCS and heart transplant (HTx) with the aim to assess short-term outcomes of VA-ECMO and identify factors associated with a poor outcome in this patient population.

Methods

Study Design and Study Population

This was a retrospective, observational study of all consecutive adult patients (>18 years of age) treated with ECMO between January 2007 and June of 2017 at 3 centers: Columbia University (New York City, NY), Duke University (Durham, NC), and Washington University (St. Louis, MO). Each center identified eligible patients and retrospectively entered them into a de-identified central database to form the RESCUE registry. Definitions of baseline characteristics and outcomes were standardized and agreed upon before data collection. Duke Clinical Research Institute served as the data coordinating and statistical analysis center. This study was approved by the institutional review board at all participating centers.

Clinical Data

Baseline demographics, clinical and laboratory characteristics, and medical history at the time of ECMO initiation were abstracted from the medical record. Indication for ECMO was identified and grouped into the following 6 categories.

HTx/primary graft dysfunction includes patients who had a history of HTx with acute cellular rejection, antibody-mediated rejection, or primary graft dysfunction.

Postcardiotomy identifies patients with persistent circulatory failure postcardiotomy.

Myocardial infarction includes patients with shock in the setting of acute coronary syndrome.

Cardiomyopathy includes patients with acute heart failure due to ischemic or nonischemic cardiomyopathy, valvular heart disease, acute myocarditis, chronic HTx rejection, or patients with cardiac arrest.

Other cardiogenic shock encompassed patients not included in the above causes of cardiogenic shock, including those with ventricular arrhythmias.

Noncardiogenic shock primarily encompassed patients with mixed shock (both vasodilatory and obstructive), sepsis, and respiratory failure.

Clinical Outcomes

Key complications were identified and abstracted from the patient’s medical chart. Complications of interest included infection (including type of infection), acute renal dysfunction (defined as increase in serum creatinine by 0.3 mg/dL), major bleeding (defined as the need for transfusion of 1 unit of packed red blood cells), coagulopathy (including disseminated intravascular coagulopathy and pulmonary embolism), chest complications (including hemothorax and pneumothorax), neurologic complications (hemorrhage, ischemic stroke, cerebral hypoxia), and vascular complications. These were documented as occurring during ECMO support or the same inpatient hospitalization. Mechanical circuit complications during ECMO support were documented. Length of stay in the intensive care unit and total hospital duration was captured. Patients were categorized by status at discharge, which included (1) patients who died during ECMO support or during the same hospitalization, (2) patients who were successfully discharged alive with HTx, (3) patients successfully discharged alive with a durable left ventricular assist device (LVAD), or (4) patients who were discharged alive without permanent cardiac support. Patients were then evaluated for 30-day outcomes.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics including demographics, medical history and comorbidities, clinical data and ECMO characteristics were summarized (overall and by status at discharge) with frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and median and quartiles for continuous variables. Factors independently associated with status at discharge (dead vs. alive) were identified using a multivariable logistic regression model. Candidate predictors for the multivariate model were identified from univariate analyses and clinical expertise.8,9 Variable selection was performed using a stepwise algorithm with significance level to enter and stay in the model set to 0.1. Hospital variation was accounted by including hospital as a fixed effect in all models. The unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios, corresponding 95% confidence intervals, and P values are presented. All analyses were performed with SAS System Release 9.4 TS1M5.

Results

Clinical Characteristics

The final study population was composed of 723 patients with similar contributions from each institution. The median age was 57 years; the majority of patients were male (69.6%) and Caucasian (60.2%) (Table 1). Postcardiotomy shock was the most common reason for ECMO support (30.7%) followed by cardiomyopathy (26.1%) and myocardial infarction (16.9%). Of note, 97 patients (13.3%) in this cohort received ECMO in the setting of cardiac arrest, but these patients were categorized according to their underlying disease process (cardiomyopathy, myocardial infarction, etc). The population had a high burden comorbidities, including diabetes (30.3%), prior coronary revascularization (31.7%), a history of stroke (7.6%), and a history of heart failure (7.6%). At the time of ECMO initiation, 76.5% of patients were already mechanically ventilated. Median serum creatinine was 1.6 mg/dL (interquartile range [IQR] 1.1–2.4 mg/dL) and median systolic blood pressure was 96 mmHg (IQR 79–112 mm Hg). Arterial cannulation occurred in the femoral artery in 396 patients (54.8%), aorta in 201 patients (27.8%), and axillary artery in 49 patients (6.8%). Patients were primarily cannulated in the operating room (49.9%) or intensive care unit (23.8%), with a minority cannulated in the catheterization laboratory (5.0%) or emergency department (0.3%). Some patients (7.7%) were also transferred from other institutions already on ECMO support.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics by Status at Discharge

| Characteristics | Overall (N = 723) |

Death (n = 433; 60%) |

Survival with HTx (n = 7; 1%) |

Survival with LVAD (n = 48; 7%) |

Survival* (n = 235; 33%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| Age (years) | |||||

| Mean (min, max) | 55 (18, 90) | 57 (20, 90) | 43 (20, 58) | 49 (20, 76) | 53 (18, 84) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 57 (46, 65) | 59 (49, 66) | 48 (25, 57) | 52 (41, 58) | 54 (44, 63) |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 220 (30.4) | 137 (62.3%) | 2 (0.9%) | 11 (5.0%) | 70 (31.8%) |

| Male | 503 (69.6) | 296 (58.8%) | 5 (1.0%) | 37 (7.4%) | 165 (32.8%) |

| Race | |||||

| Black | 110 (15.2) | 60 (54.5%) | 2 (1.8%) | 8 (7.3%) | 40 (36.4%) |

| White | 435 (60.2) | 265 (60.9%) | 4 (0.9%) | 37 (8.5%) | 129 (29.7%) |

| Other | 178 (24.6) | 108 (60.7%) | 1 (0.6%) | 3 (1.7%) | 66 (37.1%) |

| BMI | |||||

| Mean (min, max) | 30 (15, 78) | 30 (16, 78) | 25 (15, 32) | 29 (20, 44) | 29 (19, 52) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 29 (25, 34) | 29 (26, 34) | 25 (22, 30) | 27 (24, 33) | 28 (25, 34) |

| Medical history and comorbidities | |||||

| Diabetes | 219 (30.3) | 136 (62.1%) | 1 (0.5%) | 18 (8.2%) | 64 (29.2%) |

| Hypertension | 311 (43.0) | 197 (63.3%) | 3 (1.0%) | 22 (7.1%) | 89 (28.6%) |

| Prior MI | 78 (10.8) | 50 (64.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (6.4%) | 23 (29.5%) |

| Prior PCI or CABG | 229 (31.7) | 157 (68.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 8 (3.5%) | 64 (27.9%) |

| Prior stroke | 55 (7.6) | 37 (67.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (3.6%) | 16 (29.1%) |

| Prior heart failure | 44 (6.1) | 27 (61.4%) | 1 (2.3%) | 3 (6.8%) | 13 (29.5%) |

| PAD | 21 (2.9) | 16 (76.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (9.5%) | 3 (14.3%) |

| History of organ transplantation* | 7 (1.0) | 6 (85.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (14.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| History of heart transplantation | 143 (19.8) | 81 (56.6%) | 1 (0.7%) | 4 (2.8%) | 57 (39.9%) |

| History of lung transplantation | 1 (0.1) | 1 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Clinical data | |||||

| Mechanical ventilator | 553 (76.5) | 334 (60.4%) | 5 (0.9%) | 33 (6.0%) | 181 (32.7%) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | |||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 1.6 (1.1, 2.4) | 1.6 (1.2, 2.5) | 2.0 (0.9, 3.1) | 1.8 (1.0, 2.3) | 1.5 (1.1, 2.0) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | |||||

| Mean (min, max) | 96 (52, 194) | 94 (52, 194) | 94 (63, 117) | 100 (64, 165) | 98 (54, 168) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 95 (79, 112) | 93 (77, 109) | 98 (77, 112) | 98 (88, 110) | 98 (78, 115) |

| Ejection fraction before ECMO (%) | |||||

| Data available (n = ) | 341 | 206 | 3 | 24 | 108 |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 30 (15, 40) | 30 (20, 40) | 15 (15, 30) | 18 (10, 23) | 30 (20, 48) |

| ECMO characteristics | |||||

| Indication | |||||

| HTx/PGD | 59 (8.2) | 25 (42.4%) | 2 (3.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 32 (54.2%) |

| Postcardiotomy | 222 (30.7) | 142 (64.0%) | 1 (0.5%) | 8 (3.6%) | 71 (32.0%) |

| MI | 122 (16.9) | 74 (60.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (5.7%) | 41 (33.6%) |

| Cardiomyopathy | 189 (26.1) | 112 (59.3%) | 1 (0.5%) | 27 (14.3%) | 49 (25.9%) |

| Other CS | 49 (6.8) | 28 (57.1%) | 2 (4.1%) | 5 (10.2%) | 14 (28.6%) |

| Non-CS | 82 (11.3) | 52 (63.4%) | 1 (1.2%) | 1 (1.2%) | 28 (34.1%) |

| Length of ECMO support (days) | |||||

| Mean (min, max) | 6 (0, 151) | 6 (0, 84) | 35 (0, 151) | 6 (0, 22) | 5 (0, 24) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 4 (2, 7) | 4 (2, 8) | 21 (2, 38) | 4 (2, 8) | 4 (2, 6) |

BMI, body mass index; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CS, cardiogenic shock; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; HTx, heart transplant; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; MI, myocardial infarction; PAD, peripheral arterial disease; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PGD, primary graft dysfunction.

Note: Percentages in the ’Overall’ column are out of the total population (N = 723), whereas percentages in the Yes and No columns (with % symbols) use the corresponding row total.

Demographics of patients based on discharge outcomes of death, bridge to HTx, bridge to LVAD, or bridge to recovery (survival).

Excludes heart and lung transplants.

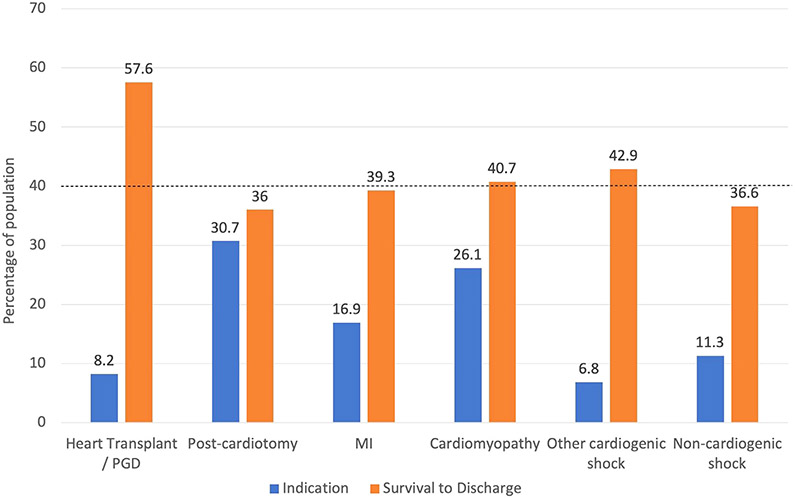

Forty percent of the study population (n = 290) survived to discharge. Of these 290 patients, 48 were discharged with LVAD and 7 patients were discharged after successful HTx. The remainder (n = 235) were discharged without need for permanent cardiac support. Post-ECMO survival to discharge differed by indication for ECMO, with the highest survival (57.6%) in patients with acute rejection of HTx and lowest in those postcardiotomy circulatory failure (36%) (Fig. 1). Patients had a median intensive care unit length of stay of 13 days (IQR 5–26 days) and hospital length of stay of 19 days (IQR 5–39 days) (Supplementary Fig. S1). Of the patients who died on ECMO support, the median time on ECMO support was 4 days (IQR 2–8 days) (Supplementary Fig. S2a). For patients who survived to decannulation but died during hospitalization, median time of ECMO support was 5 days (IQR 3–9 days) and median time of hospitalization was 23 days (IQR 14–39 days) (Supplementary Fig. S2b).

Fig. 1.

Indication for ECMO and survival to discharge by indication. Survival to discharge includes successful bridge to LVAD or heart transplant. Dashed line indicates survival for entire cohort. MI, myocardial infarction; PGD, primary graft dysfunction.

Complications

The most commonly encountered complications during ECMO hospitalization included acute renal dysfunction, which occurred in 44.8% of patients, and major bleeding, which occurred in 41.1% (Table 2). Upon discharge from the hospital (whether deceased or discharged alive), 20.7% of patients were on renal replacement therapy (although the data were only available for 465 patients).

Table 2.

Complications Occurring on ECMO or During Hospitalization

| Complication | On ECMO | During Hospitalization |

Death | Survival With HTx |

Survival With LVAD |

Survival* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 723) | (n = 723) | (n = 433) | (n = 7) | (n = 48) | (n = 235) | |

| Infection | 154 (21.3) | 241 (33.3) | 132 (54.8%) | 3 (1.2%) | 18 (7.5%) | 88 (36.5%) |

| Acute renal dysfunction | 257 (35.5) | 312 (44.8) | 230 (73.7%) | 4 (1.3%) | 16 (5.1%) | 62 (19.9%) |

| Hematologic complications | ||||||

| Major bleeding | 261 (36.1) | 297 (41.1) | 199 (67.0%) | 2 (0.7%) | 15 (5.1%) | 81 (27.3%) |

| Clinically significant coagulopathy | 103 (14.2) | 110 (15.2) | 85 (77.3%) | 1 (0.9%) | 7 (6.4%) | 17 (15.5%) |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulopathy | 16 (2.2) | 17 (2.4) | 17 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Deep venous thrombosis | 19 (2.6) | 41 (5.7) | 15 (36.6%) | 1 (2.4%) | 5 (12.2%) | 20 (48.8%) |

| Pulmonary embolism | 3 (0.4) | 4 (0.6) | 2 (50.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (50.0%) |

| Chest complications | ||||||

| Hemothorax | 25 (3.5) | 36 (5.0) | 22 (61.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (8.3%) | 11 (30.6%) |

| Pneumothorax | 22 (3.0) | 31 (4.3) | 22 (71.0%) | 1 (3.2%) | 2 (6.5%) | 6 (19.4%) |

| Neurologic complications | ||||||

| Diffuse cerebral edema/hypoxic encephalopathy | 28 (3.9) | 38 (5.3) | 33 (86.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.6%) | 4 (10.5%) |

| Intracranial hemorrhage/hemorrhagic stroke | 17 (2.4) | 30 (4.1) | 22 (73.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (3.3%) | 7 (23.3%) |

| Ischemic stroke/embolization | 17 (2.4) | 36 (5.0) | 24 (66.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (5.6%) | 10 (27.8%) |

| Seizures | 3 (0.4) | 5 (0.7) | 3 (60.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (40.0%) |

| Vascular complications | ||||||

| Limb ischemia | 88 (12.2) | 88 (12.2) | 63 (71.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (3.4%) | 22 (25.0%) |

| Fasciotomy | 25 (3.5) | 25 (3.5) | 20 (80.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (4.0%) | 4 (16.0%) |

| Peripheral wound | 12 (1.7) | 12 (1.7) | 6 (50.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 6 (50.0%) |

| Hyperperfusion | 3 (0.4) | 3 (0.4) | 2 (66.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (33.3%) |

| Circuit-related technical complications or device malfunction | ||||||

| Air Embolism | 1 (0.1) | - | 1 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Cannula dislodgement | 6 (0.8) | - | 5 (83.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (16.7%) |

| Oxygenator failure requiring exchange | 8 (1.1) | - | 5 (62.5%) | 1 (12.5%) | 1 (12.5%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| Pump malfunction | 6 (0.8) | - | 5 (83.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (16.7%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Thrombosis requiring circuit change | 8 (1.1) | - | 7 (87.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| Tubing rupture | 1 (0.1) | - | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (100.0%) |

ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; HTx, heart transplant; LVAD, left ventricular assist device.

Number and percentage of patients with specific complications occurring on ECMO and during hospitalization with associated discharge status.

Survival without transplant or LVAD.

Hematologic complications were common and included bleeding requiring transfusion in 41.1% of patients, significant coagulopathy in 15.2%, and deep vein thrombosis in 5.7%. The majority of hematologic complications occurred during ECMO support. Disseminated intravascular coagulopathy was rare (2.4%), but all patients with this complication died.

Neurologic complications, including diffuse cerebral edema or hypoxic encephalopathy, occurred in 5.3% of patients, ischemic/embolic stroke in 5%, and intracranial hemorrhage in 4.1%. Of the 109 patients with these complications, 82 (75.2%) died.

All vascular complications occurred during ECMO support. Of the 12.2% of patients who developed limb ischemia, only 3.5% required fasciotomy. Circuit complications on ECMO were overall very rare, with oxygenator failure requiring exchange and thrombosis requiring circuit change occurring in 8 patients (1.1%) each.

Patients on ECMO were prone to infection, which occurred in 241 patients (33.3%) (Table 3). Eighty-four of these patients developed more than 1 infectious complication during their hospitalization. The most common infections were respiratory infections (n = 165), urinary tract infections (n = 51), and bacteremia (n = 51). Surgical wound infections and cannulation site infections were rare.

Table 3.

Infections Occurring During Hospitalization

| Infection Type | Anytime During Hospitalization (n = 723) |

Death | Survival with HTx | Survival with LVAD | Survival* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteremia | 51 (7.1) | 24 (47.1%) | 1 (2.0%) | 5 (9.8%) | 21 (41.2%) |

| Sepsis | 18 (2.5) | 15 (83.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (16.7%) |

| Gastrointestinal Tract | 30 (4.1) | 16 (53.3%) | 1 (3.3%) | 3 (10.0%) | 10 (33.3%) |

| Respiratory (rhinitis, sinusitis, pharyngitis, bronchitis, pneumonia) | 165 (22.8) | 90 (54.5%) | 1 (0.6%) | 10 (6.1%) | 64 (38.8%) |

| Skin- peripheral cannulation site | 3 (0.4) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (100.0%) |

| Surgical wound infection, incisional | 18 (2.5) | 10 (55.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (11.1%) | 6 (33.3%) |

| Surgical wound infection, deep | 7 (1.0) | 5 (71.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (14.3%) | 1 (14.3%) |

| Urinary tract (vaginitis, cervicitis, urethritis, cystitis, pyelonephritis) | 51 (7.1) | 22 (43.1%) | 1 (2.0%) | 6 (11.8%) | 22 (43.1%) |

HTx, heart transplant; LVAD, left ventricular assist device.

Number and percentage of patients with specific types of infections and associated discharge status.

Survival without transplant or LVAD.

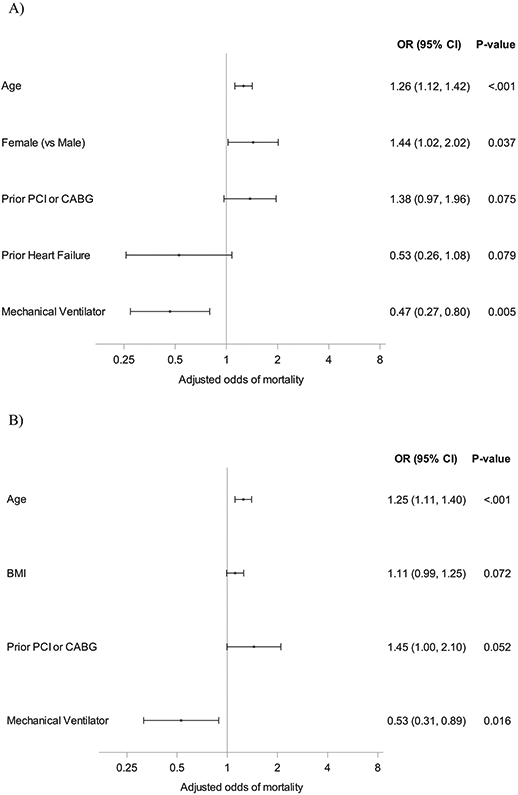

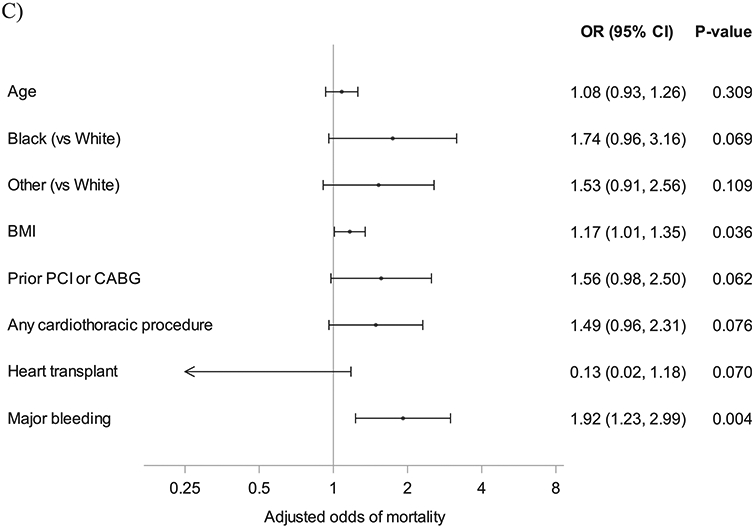

Factors Associated With Mortality

We performed a multivariable regression analysis to identify the factors associated with mortality during ECMO (Supplementary Table 1a, Fig. 2a), during ECMO hospitalization (Supplementary Table 1b, Fig. 2b), or specifically after ECMO if patients survived to decannulation (Supplementary Table 1c, Fig. 2c). After adjustment, only older age (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.26, IQR 1.12–1.42, P < .001) and female sex (aOR 1.44, IQR 1.02–2.02, P = .037) were found to be predictive of death on ECMO. Alternatively, use of mechanical ventilation (aOR 0.47, IQR 0.27–0.80, P = .005) was associated lower odds of death while on ECMO. Given the association of sex with mortality on ECMO support, Kaplan–Meier estimates of mortality after ECMO initiation stratified by sex were modeled (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of patient characteristics and death. (A) Associations between patient characteristics and death on ECMO. (B) Associations between patient characteristics and death on ECMO or hospitalization. (C) Associations between patient characteristics and death after decannulation. BMI, body mass index; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

When assessing for factors associated with mortality during ECMO or ECMO hospitalization, age (aOR 1.25, IQR 1.11–1.40, P < .001) was found to be a risk factor and prior history of coronary revascularization (aOR 1.45, IQR 1.00–2.10, P = .052) was nominally significant. Use of mechanical ventilation (aOR 0.53, IQR 0.361–0.890, P = .016) was associated with a decreased odds of mortality (aOR 0.53, IQR 0.31–0.89, P = .016). Among those patients who survived to decannulation, a higher body mass index (BMI) (aOR 1.17, IQR 1.01–1.35, P = .036) and major bleeding while on ECMO support (aOR 1.92, IQR 1.23–2.99, P = .004) were associated with an increased risk of death.

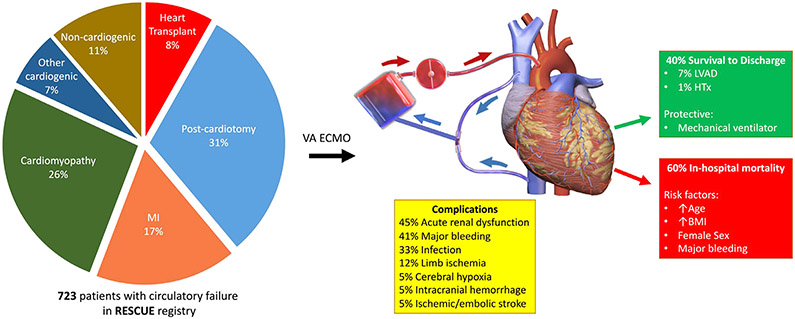

Discussion

In an era of expanding use of MCS, we describe a large, contemporary cohort of 723 patients treated with VA-ECMO at 3 quaternary centers (the RESCUE registry) with expertise in management of circulatory failure (Fig. 3). The main indications for deployment of VA-ECMO were postcardiotomy shock (31%), cardiomyopathy (including acute heart failure decompensation) (26%), and myocardial infarction (17%). During hospitalization for VA-ECMO, patients had a high burden of complications, including acute renal dysfunction (45%), major bleeding (41%), and infection (33%). Of 723 patients supported with VA-ECMO, only 40% (n = 290) survived to hospital discharge. Only a minority of patients received LVAD (n = 48) or HTx (n = 7); the remainder (n = 235) were discharged without need for permanent cardiac support. Risk factors for mortality included older age, higher BMI, female sex, and major bleeding while on ECMO support. The use of mechanical ventilation at the time of ECMO initiation was associated with improved outcomes.

Fig. 3.

Among 723 patients in the RESCUE registry, the primary indication for VA ECMO was postcardiotomy shock followed by cardiomyopathy (including acute heart failure) and myocardial infarction. Complications were common and included acute renal dysfunction, bleeding, and infection. Only 40% survived to discharge, with few requiring permanent cardiac support. Risk factors for mortality during or after ECMO included older age, higher BMI, female sex, and major bleeding on ECMO support. Mechanical ventilation was protective. BMI, body mass index; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; HTx, heart transplant; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; MI, myocardial infarction; VA, venoarterial. Image credit: Blausen Medical Communications, Inc.

Indications

Indications for VA-ECMO noted in our study are similar to other national data. A previous single-institution study found the top 3 causes for VA-ECMO initiation to be postcardiotomy failure (21%), acute or chronic heart failure (23%), and acute myocardial infarction (28%).9 Data from an analysis using the Nationwide Inpatient Sample demonstrates postcardiotomy failure as an indication for ECMO initiation was 37.9%, down from 56.9% in 2002,10 highlighting that ECMO is being increasingly used outside of the operating room for a variety of conditions, including during cardiopulmonary resuscitation11 and as a bridge therapy to HTx.7,8 Previous studies have been able to find significant differences in survival based on indication for ECMO, where myocarditis,12 refractory ventricular arrhythmias,13 and pulmonary embolism9 were favorable indications, whereas cardiac arrest14-16 and postcardiotomy shock10 tend to be unfavorable. However, after multivariable adjustment in our cohort, we were unable to associate the indication for ECMO with subsequent mortality. This result is likely related to the overall low numbers of patients with pulmonary emboli, myocarditis, and cardiac arrest in our cohort, and the fact that these conditions were all grouped into a composite called “cardiomyopathy” for the purposes of our analysis.

Complications

Despite receiving care at high-volume centers with expertise in management of ECMO, our cohort had a high incidence of complications occurring during ECMO support or the remainder of the hospitalization, including acute renal dysfunction (45%), major bleeding (41%), and infection (33%). A meta-analysis of 1866 patients conducted in 2014 had similar rates of complications, with acute kidney injury 56%, major bleeding 42%, significant infection 30%, limb ischemia 17%, and stroke 5%.17

Significant neurologic complications during a hospitalization for ECMO are relatively common (occurring in as many as 11% of patients) and have been associated with higher mortality, longer hospital stay, and the likelihood of discharge to an assisted living facility.18 In our cohort, 4.1% of patients suffered intracranial hemorrhage and 5.0% experienced an ischemic or embolic stroke, but we did not find that neurologic complications decreased the odds of survival on multivariate analysis, likely owing to the low overall event rates. However, among the cohort of patients who suffered a stroke, hemorrhage, or global ischemia, survival to hospital discharge was less than 30%. Of the complications that occurred during ECMO support, only major bleeding, after multivariable adjustment, was found to be a risk factor for mortality in our cohort. Complications that have predicted mortality in other cohorts include oliguria and the need for dialysis,12,19-23 stroke,19 and limb ischemia16 during ECMO support.

Outcomes

In our cohort, 60% of patients (n = 433) died during hospitalization, consistent with prior reports.9,14,17,24 Data from a large, international registry of more than 300 ECMO centers, the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization registry, demonstrated a 41% survival to discharge for patients who had ECMO initiated for cardiac etiologies.4 This survival rate is similar to that found in an analysis using the Nationwide Inpatient Sample, where 43.3% of patients treated with ECMO between 2007 and 2014 survived to discharge.25 In that study, 3.5% of patients were bridged to LVAD, similar to a recent analysis of the Society for Thoracic Surgeons database, which demonstrates that, of 19,825 patients receiving durable MCS between January 2008 and December 2017, only 933 patients (4.7%) were bridged via ECMO.26 Compared with other critically ill patients (Interagency for Mechanical Circulatory Support profile 1), patients requiring ECMO had an inferior 12-month survival, although a high hazard for death occurred in the first 6 months after MCS implantation. However, after propensity matching for important clinical variables, survival outcomes were similar.26 Data from the International Society of Heart and Lung Transplant indicate that only 1% of patients receiving HTx are bridged from ECMO support, in line with observations from our cohort.25,27 Thus, aggregate data from even the largest registries highlight that (1) durable cardiac support is often not used after ECMO initiation and (2) ECMO continues to be associated with high short-term mortality, findings likely related to poor patient substrate (comorbidities, end-organ dysfunction in the setting of shock) and complications associated with ECMO use.

Risk Factors

We sought to determine the risk factors for mortality in our large cohort of patients to inform better selection of patients for this therapy. We found that older age, female sex, higher BMI, and major bleeding on ECMO support are associated with an increased risk of mortality, whereas the use of mechanical ventilation at time of ECMO initiation mitigated risk. Age has been repeatedly found to be an independent predictor of mortality in numerous other cohorts,9,13,15,16,19,21,28-31 perhaps because age best captures, in a single variable, many of the other characteristics that could predispose to adverse outcomes, such as more baseline end-organ dysfunction,30 an inability to tolerate multiple insults, and frailty. Indeed, in our cohort, mortality rates while on ECMO support increased from 26.3% in those aged 35 to 44 years of age to 53.7% in those 75 years or older (Supplementary Fig. S4). Female sex has also been found to be a poor prognosticator 12,28,31 as have the extremes of BMI,29,31,32 highlighting that our findings are consistent with those of other cohorts and seem to be generalizable. Other baseline factors that seem to predict ECMO outcomes include history of diabetes mellitus29,33 and elevated bilirubin and lactate at time of ECMO initiation.9,20,21,29

Various models incorporating baseline characteristics have been developed to risk stratify patients before ECMO initiation. The SAVE score was developed from 3846 patients in the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization registry and includes age, weight, indication for ECMO, pre-ECMO organ dysfunction, duration of intubation and ventilator parameters, blood pressure, and serum bicarbonate and stratifies patients into 5 risk classes, which correlate with post-ECMO survival.13 Although a longer duration of intubation in the SAVE cohort was associated with higher odds of mortality, mechanical ventilation was found to be a protective factor in our cohort, although our data do not report duration of intubation. A possible explanation is that mechanical ventilation may be representative of a more controlled setting for ECMO initiation (in the cardiac intensive care unit for a patient with slowly worsening shock) as opposed to more emergent initiation (out-of-hospital cardiac arrest), which may occur before or during intubation. Three of our predictive factors (age, female sex, BMI) are also a part of another score, the ENCOURAGE score, validated to predict outcomes after acute myocardial infarction VA-ECMO use.31

Future Directions

VA-ECMO can serve as life-saving therapy for patients with cardiovascular collapse, but improvements in patient outcomes associated with this therapy will require better patient selection and refinement in care delivery, possibly including (1) the development of multidisciplinary shock teams for early identification and treatment of decompensating patients, (2) early assessment for heart failure destination therapies, (3) protocols to frequently assess readiness for weaning, and (4) expertise in the management of ECMO-related complications. Our study highlights that, despite care in high-volume centers with expertise in the management of advanced heart failure, patients requiring VA-ECMO have high morbidity and mortality, and describes risk factors associated with poor outcomes to better assist clinicians in patient selection. Specifically, our study finds that, for each additional decade of age most represented in our study population (ages 40–70), the risk of mortality during an ECMO hospitalization increases by 25%. Combined with numerous other studies finding it to be an independent predictor of mortality,9,13,15,16,19,21,28-31 age represents a robust prognosticator that clinicians can easily use at the bedside. Although various consensus documents and expert panels highlight advanced age as a relative contraindication to ECMO,5,34,35 our study provides granularity to this recommendation and can help to inform future guidelines. For now, clinicians should use the available risk models in the context of multidisciplinary discussions to select patients most appropriate for this therapy. Further refinements in patient selection will require assessment in clinical trials in specific populations, as is currently being done in the EUROSHOCK (Testing the Value of Novel Strategy and Its Cost Efficacy in Order to Improve the Poor Outcomes in Cardiogenic Shock, NCT04184635) and ANCHOR (Assessment of ECMO in Acute Myocardial Infarction Cardiogenic Shock, NCT03813134) trials, where ECMO is being compared with the standard of care in the acute myocardial infarction population.

Study Limitations

This study pools data from 3 large centers with expertise in ECMO care to provide a contemporary description of outcomes associated with this evolving therapy. The primary limitations of this study lie in its retrospective, observational nature, which will implicitly introduce bias into patient selection and management choices. Data were also collected from 3 different centers by a different team of reviewers. Nonetheless, a centralized database and data dictionary ensured accurate capture of clinical events with low rates of missingness for the majority of data. Of note, our definition of major bleeding is different than that used by Extracorporeal Life Support Organization registry, which defines it as need for 3 units of packed red blood cells in 24 hours, and thus may overestimate bleeding events. This definition was chosen at the study outset, because the authors felt that bleeding requiring any transfusion would be considered clinically significant. This consideration becomes especially important in patients being evaluated for cardiac transplantation, where transfusion carries the risk of allosensitization. Of note, all 3 centers use similar anticoagulation protocols with target activated partial thromboplastin times of 60 to 80 seconds, although adjustments in targets are individualized to patient-level risk of bleeding and thrombosis.

Conclusions

In this large, contemporary, multicenter cohort of patients undergoing VA-ECMO, in-hospital mortality remained at 60% despite expertise in care delivery, and there was a high rate of complications including acute renal insufficiency, major bleeding, and infection. Factors most associated with mortality among patients treated with VA-ECMO were age, gender, BMI, and bleeding while on ECMO. These insights will help to guide patient selection for a therapy that is potentially life saving, but is associated with high morbidity and mortality.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This work was funded internally by the Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, North Carolina.

Declaration of competing interest

Dr Loungani receives research support from Pfizer and Boston Scientific. Dr Fudim serves as a consultant for AxonTherapies and Daxor. Dr Samsky is supported by a National Institutes of Health T32 training grant (grant HL069749), and receives research support from Boston Scientific. Dr DeVore receives research funding from the American Heart Association, Amgen, Bayer, Intra-Cellular Therapies, Luitpold Pharmaceuticals, the NHLBI, Novartis, and PCORI. He also provides consulting services for Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, InnaMed, LivaNova, Mardil Medical, Novartis, Procyrion, scPharmaceuticals, and Zoll. He has also received personal fees from Abbott. All other authors report no relevant disclosures.

Footnotes

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2020.11.026.

References

- 1.Stretch R, Sauer CM, Yuh DD, Bonde P. National trends in the utilization of short-term mechanical circulatory support: incidence, outcomes, and cost analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;64:1407–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Enezate T, Eniezat M, Thomas J. Utilization and outcomes of temporary mechanical circulatory support devices in cardiogenic shock. Am J Cardiol 2019;124:505–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berg DD, Barnett CF, Kenigsberg BB, Papolos A, Alviar CL, Baird-Zars VM, et al. Clinical practice patterns in temporary mechanical circulatory support for shock in the Critical Care Cardiology Trials Network (CCCTN) registry. Circ Heart Fail 2019;12:e006635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thiagarajan RR, Barbaro RP, Rycus PT, Mcmullan DM, Conrad SA, Fortenberry JD, et al. Extracorporeal Life Support Organization registry international report 2016. ASAIO J 2017;63:60–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keebler ME, Haddad EV, Choi CW, McGrane S, Zalawadiya S, Schlendorf KH, et al. Venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in cardiogenic shock. JACC Heart Fail 2018;6:503–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacLaren G, Fisher D, Brodie D. Preparing for the most critically ill patients with COVID-19: the potential role of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. JAMA 2020;323:1245–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lui C, Fraser CD, Suarez-Pierre A, Zhou X, Zehr KJ, Choi CW, et al. Comparison of ECMO patients bridged to LVAD vs bridged to transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 2019;38:S32. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trivedi JR, Slaughter MS. Unintended consequences of changes in heart transplant allocation policy: impact on practice patterns. ASAIO J 2020;66:125–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carroll BJ, Shah RV, Murthy V, McCullough SA, Reza N, Thomas SS, et al. Clinical features and outcomes in adults with cardiogenic shock supported by extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Am J Cardiol 2015;116:1624–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCarthy FH, McDermott KM, Kini V, Gutsche JT, Wald JW, Xie D, et al. Trends in U.S. extracorporeal membrane oxygenation use and outcomes: 2002-2012. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2015;27:81–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richardson AC, Schmidt M, Bailey M, Pellegrino VA, Rycus PT, Pilcher DV. ECMO Cardio-Pulmonary Resuscitation (ECPR), trends in survival from an international multicentre cohort study over 12-years. Resuscitation 2017;112:34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Combes A, Leprince P, Luyt C-E, Bonnet N, Trouillet J-L, Léger P, et al. Outcomes and long-term quality-of-life of patients supported by extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for refractory cardiogenic shock. Crit Care Med 2008;36:1404–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmidt M, Burrell A, Roberts L, Bailey M, Sheldrake J, Rycus PT, et al. Predicting survival after ECMO for refractory cardiogenic shock: the survival after veno-arterial-ECMO (SAVE)-score. Eur Heart J 2015;36:2246–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xie A, Phan K, Yi-Chin Tsai M, Yan TD, Forrest P. Venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for cardiogenic shock and cardiac arrest: a meta-analysis. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2015;29:637–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Batra J, Toyoda N, Goldstone AB, Itagaki S, Egorova NN, Chikwe J. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in New York State. Circ Heart Fail 2016;9:e003179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaushal M, Schwartz J, Gupta N, Im J, Leff J, Jakobleff WA, et al. Patient demographics and extracorporeal membranous oxygenation (ECMO)-related complications associated with survival to discharge or 30-day survival in adult patients receiving venoarterial (VA) and venovenous (VV) ECMO in a quaternary care urban center. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2019;33:910–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng R, Hachamovitch R, Kittleson M, Patel J, Arabia F, Moriguchi J, et al. Complications of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for treatment of cardiogenic shock and cardiac arrest: a meta-analysis of 1,866 adult patients. Ann Thorac Surg 2014;97:610–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nasr DM, Rabinstein AA. Neurologic complications of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Clin Neurol 2015;11:383–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lan C, Tsai P-R, Chen Y-S, Ko W-J. Prognostic factors for adult patients receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation as mechanical circulatory support-a 14-year experience at a medical center. Artif Organs 2010;34:E59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burrell AJC, Pellegrino VA, Wolfe R, Wong WK, Cooper EJ, Kaye DM, et al. Long-term survival of adults with cardiogenic shock after venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Crit Care 2015;30:949–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu M-Y, Lin P-J, Lee M-Y, Tsai F-C, Chu J-J, Chang Y-S, et al. Using extracorporeal life support to resuscitate adult postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock: treatment strategies and predictors of short-term and midterm survival. Resuscitation 2010;81:1111–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aubin H, Petrov G, Dalyanoglu H, Saeed D, Akhyari P, Paprotny G, et al. A suprainstitutional network for remote extra-corporeal life support: a retrospective cohort study. JACC Heart Fail 2016;4:698–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen W-C, Huang K-Y, Yao C-W, Wu C-F, Liang S-J, Li C-H, et al. The modified SAVE score: predicting survival using urgent veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation within 24 hours of arrival at the emergency department. Crit Care 2016;20:336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sy E, Sklar MC, Lequier L, Fan E, Kanji HD. Anticoagulation practices and the prevalence of major bleeding, thromboembolic events, and mortality in venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Crit Care 2017;39:87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shah Z, Vuddanda V, Yin M, Wever-Pinzon O, Nativi-Nicolau J, Drakos S, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation as a bridge to heart transplant versus left ventricular assist device: analysis of a multicenter, nationwide database. J Heart Lung Transplant 2018;37:S28. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loyaga-Rendon RY, Boeve T, Tallaj J, Lee S, Leacche M, Lotun K, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation as a bridge to durable mechanical circulatory support. Circ Heart Fail 2020;13:e006387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lund LH, Khush KK, Cherikh WS, Goldfarb S, Kucheryavaya AY, Levvy BJ, et al. The registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: thirty-fourth adult heart transplantation report—2017; focus theme: allograft ischemic time. J Heart Lung Transplant 2017;36:1037–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murashita T, Eya K, Miyatake T, Kamikubo Y, Shiiya N, Yasuda K, et al. Outcome of the perioperative use of percutaneous cardiopulmonary support for adult cardiac surgery: factors affecting hospital mortality. Artif Organs 2004;28:189–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rastan AJ, Dege A, Mohr M, Doll N, Falk V, Walther T, et al. Early and late outcomes of 517 consecutive adult patients treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for refractory postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2010;139. 302–11.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lorusso R, Gelsomino S, Parise O, Mendiratta P, Prodhan P, Rycus P, et al. Venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for refractory cardiogenic shock in elderly patients: trends in application and outcome from the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO) registry. Ann Thorac Surg 2017;104:62–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muller G, Flecher E, Lebreton G, Luyt C-E, Trouillet J-L, Bréchot N, et al. The ENCOURAGE mortality risk score and analysis of long-term outcomes after VA-ECMO for acute myocardial infarction with cardiogenic shock. Intensive Care Med 2016;42:370–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aso S, Matsui H, Fushimi K, Yasunaga H. In-hospital mortality and successful weaning from venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: analysis of 5,263 patients using a national inpatient database in Japan. Crit Care 2016;20:80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garan AR, Malick WA, Habal M, Topkara VK, Fried J, Masoumi A, et al. Predictors of survival for patients with acute decompensated heart failure requiring extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation therapy. ASAIO J 2019;65:781–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Diepen S, Katz JN, Albert NM, Henry TD, Jacobs AK, Kapur NK, et al. Contemporary management of cardiogenic shock: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017;136:e232–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.(ELSO) ELSO. Guidelines for Adult Cardiac Failure. www.elso.org/Portals/0/IGD/Archive/FileManager/e76ef78eabcu-sersshyerdocumentselsoguidelinesforadultcardiacfailure1.3.pdf 2013.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.