Abstract

BACKGROUND

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a highly contagious infection caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 virus and has a unique underlying pathogenesis. Hemodialysis (HD) patients experience high risk of contamination with COVID-19 and are considered to have higher mortality rates than the general population by most but not all clinical series. We aim to highlight the peculiarities in the immune state of HD patients, who seem to have both immune-activation and immune-depression affecting their outcome in COVID-19 infection.

CASE SUMMARY

We report the opposite clinical outcomes (nearly asymptomatic course vs death) of two diabetic elderly patients infected simultaneously by COVID-19, one being on chronic HD and the other with normal renal function. They were both admitted in our hospital with COVID-19 symptoms and received the same treatment by protocol. The non-HD sibling deteriorated rapidly and was intubated and transferred to the Intensive Care Unit, where he died despite all supportive care. The HD sibling, although considered more “high-risk” for adverse outcome, followed a benign course and left the hospital alive and well.

CONCLUSION

These cases may shed light on aspects of the immune responses to COVID-19 between HD and non-HD patients and stimulate further research in pathophysiology and treatment of this dreadful disease.

Keywords: Case report, Hemodialysis, Siblings, COVID-19, Host response, Immune-activation, Immune-depression

Core Tip: The pandemic of novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 is life threatening only for a limited subgroup of patients who manifest severe respiratory failure (SRF). Hemodialysis (HD) patients are in a paradox state of immune-activation and immune-depression, and it is not yet clear if they are more or less vulnerable to SRF. We report the case of two siblings with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection at the same time and opposite outcome, death of the brother with normal renal function and rather indolent course of the brother on HD. This case challenges the relevance of HD as an independent risk factor for COVID-19 associated mortality.

INTRODUCTION

The pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) by the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) originating from China on December 2019 poses still a major health and financial problem worldwide[1]. It is a respiratory virus, highly contagious mostly by large droplet transmission, and causes common cold or no symptoms in nearly 80%. However, in a subset of 20%, the infection causes sudden deterioration with severe pneumonia and respiratory failure necessitating intubation, a condition with high mortality rates[2].

Stable hemodialysis (HD) patients present with the paradox of immune-activation and immune-depression[3]. We report the case of two siblings infected at the same time, one of them on maintenance HD due to end stage renal disease (ESRD) (patient 1, HD) and the other with normal renal function (patient 2, non HD). Although ESRD is associated with increased overall mortality compared to age-matched controls[4] and in particular with COVID-19[5,6], the sibling on HD survived and the other died from multiorgan failure attributed to COVID-19 infection. This case report emphasizes the need for further studies to discover prognostic markers, which will allow us to plan more effective treatment algorithms.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

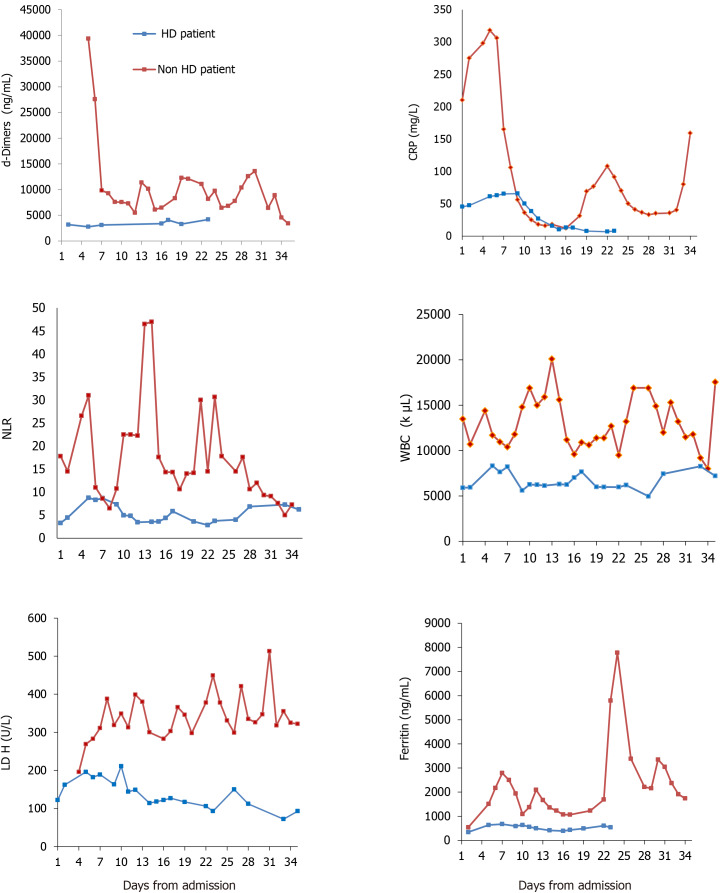

We report the contrasting outcome of two Caucasian diabetic, elderly brothers simultaneously infected by COVID-19 and referred to our hospital early in the course of disease. The laboratory timeline from admission to outcome is shown in Figure 1. Table 1 depicts the main clinical and laboratory characteristics on day 1 and during admission.

Figure 1.

Laboratory parameters on day 1 and during admission for patient 1 on hemodialysis and patient 2 with normal renal function on admission (non-hemodialysis). CRP: C-reactive protein; LDH: Lactate dehydrogenase; NLR: Neutrophils to lymphocytes ratio; WBC: White blood count.

Table 1.

Clinical and laboratory characteristics on day 1 and during admission

|

Clinical and laboratory characteristics

|

Patient 1, HD

|

Patient 2, non HD

|

| Age | 65 | 78 |

| Sex | M | M |

| Race | Caucasian | Caucasian |

| BMI | 28 | 31 |

| Malnourished | Yes | No |

| Diabetes mellitus | Type 2 | Type 2 |

| Other | PAD | No |

| Days from illness onset to admission | 3 | 3 |

| Fever | Yes | Yes |

| Cough | No | Yes |

| Dyspnea | No | No |

| CT score | 10 | 19 |

| Respiratory failure | No | Yes |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | Yes | Yes |

| WBC count (k/μL) | 5900 | 13.500 |

| Neutrophil count | 4035 | 12.015 |

| Lymphocyte count (k/μL) | 1227 | 675 |

| NLR | 3.3 | 17.8 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 341 | 542 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 45.3 | 210 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.5 | 4.9 |

| D- dimers (ng/mL) | 3191 | 39364 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) (MDRD) | < 15 | 65 |

| Frailty index | 7 | 7 |

| Charlson comorbidity index | 7 | 4 |

BMI: Body mass index; CRP: C-reactive protein; CT: Computed tomography; eGFR: Estimated glomerular filtration rate; HD: Hemodialysis; M: Men; MDRD: Modification of diet in renal disease; NLR: Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio; PAD: Peripheral artery disease; WBC: White blood cells.

Patient 1: The younger brother, a 65-year-old male, complained of malaise and developed mild fever (37.3 °C) on April 23, 2020.

Patient 2: The older brother, a 78-year-old male, developed non-productive cough, mild sore throat and fever up to 38 °C on April 20, 2020.

History of present illness

Patient 1: He had been hospitalized and treated in a private clinic with HD facilities for diabetic foot and had completed a 10-d course with antibiotics (ticarcillin/ clavulanic acid) when he developed fever.

Patient 2: He had been visiting his brother regularly during his hospitalization for his leg infection.

Patients 1 and 2: SARS-CoV-2 was detected in a nasopharyngeal swab specimen by real-time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction on April 23, and the next day both siblings were admitted to our hospital.

History of past illness

Patient 1: ESRD due to diabetic nephropathy, maintained on regular HD for 6 years.

Patient 2: Obese patient with type 2 diabetes mellitus and normal kidney function.

Personal and family history

Patients 1 and 2 have no special personal and family history.

Physical examination

Patient 1: Clinical examination on admission revealed a malnourished man [body mass index (ΒΜΙ) 28 kg/m2] looking older than the stated age, with bilateral 2+ leg edema, temperature of 37.3 °C, pulse rate of 70 beats per min, blood pressure of 90/60 mmHg, respiratory rate of 22 breaths per min and oxygen saturation 98% while breathing ambient air. Lung auscultation revealed bibasilar crackles.

Patient 2: Clinical examination on admission revealed an obese man (ΒΜΙ 31 kg/m2), temperature of 38.3 °C, pulse rate of 85 beats per min, blood pressure of 128/80 mmHg, respiratory rate of 22 breaths per min and oxygen saturation 95% on room air.

Laboratory examinations

Laboratory assessment shown in Table 1 and Figure 1.

Patient 1: Normal white blood cell (WBC) count with lymphocytes > 1000/μL and mildly elevated C-reactive protein (CRP 45.3 mg/L) and ferritin (342 ng/mL).

Patient 2: Leukocytosis (WBC 12015/μL) with lymphopenia (675/μL) and high CRP (210 mg/L) and ferritin (542 ng/mL).

Imaging examinations

Chest computed tomography (CT) revealed bilateral pleural effusions and ground glass infiltration with central distribution, characteristic of COVID-19 pneumonia[7].

For patient 1, pulmonary infiltration was < 10%, corresponding to a CT severity score of 10[7]; while for patient 2, pulmonary infiltration was > 25%-49%, corresponding to a CT severity score of 19.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

COVID-19 disease with respiratory involvement. Patient 1 was considered also hypervolemic on admission.

TREATMENT

Patients 1 and 2

They were both treated for COVID-19, according to the current protocol of the Infectious Disease department, with a loading dose of 200 mg of hydroxychloroquine at day 1, followed by 100 mg b.i.d. for 5 d, along with azithromycin 500 mg daily during the same period time. They both received prophylactic anticoagulation with tinzaparin 3500 IU subcutaneously once daily.

Patient 1 continued his thrice weekly HD schedule and reached euvolemia within the next week by increasing dialysis ultrafiltration gradually. On HD day, tinzaparin was given only during HD session, at the dialysis circuit.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

Patient 1 had a mild COVID-19 disease, while patient 2 deteriorated rapidly into the critical form with severe respiratory failure and eventually died.

Patient 1: On April 30, 2020, while on acetylsalicylic acid 100 mg and tinzaparin 3500 IU daily, he developed severe gastrointestinal bleeding, reaching a nadir value of hemoglobin of 8.1 g/dL from a baseline value of 10.1 g/dL on admission and received two units of red blood cells and one unit of fresh frozen plasma. Anticoagulation was stopped until hemoglobin stabilization. Colonoscopy was not diagnostic. His hospitalization was uneventful thereafter, without respiratory distress or need for supplementary oxygen. He was discharged after two negative SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction tests on May 14, 2020.

Patient 2: On the second hospitalization day he developed severe respiratory distress syndrome requiring intubation and admission to the intensive care unit (ICU). He was placed on intermittent prone position for the first 3 d in ICU with satisfactory response. On day 2 in ICU, his condition was complicated by fast atrial fibrillation, circulatory collapse and acute kidney injury (AKI). Tocilizumab, an interleukin-6 inhibitor, was given intravenously at 8 mg/kg (750 mg) in two infusions, 12 h apart, as per ICU protocol for severe COVID-19. After 2 d, treatment with continuous renal replacement treatment (hemodiafiltration) for AKI was initiated. On day 8 in ICU, he suffered from gastrointestinal bleeding requiring red blood cell transfusions. On May 12, 2020, he developed a gram-negative bacteremia with Pseudomonas aeruginosa and a pneumonia due to Acinetobacter baumanni. On May 15, he was also offered a 2 h duration hemoadsorption-session with hemoadsorber HA-330 (Jafron, adsorbent material styrene divinylbenzene copolymers, Jafron, Zhuhai, China) as per ICU protocol. HA-330 filters are used as “salvage therapy” in critically ill septic patients with multiorgan failure (renal failure included). Hemoadsorption was not continued because of lack of improvement and on May 21, 2020 he died because of septic shock and multiorgan failure. SARS-CoV-2 was detected in repeated nasopharyngeal swab specimens throughout the ICU stay.

DISCUSSION

We present the case of two elderly diabetic brothers infected with COVID-19. The younger brother on HD for 6 years, complicated with peripheral artery disease, diabetic foot with gangrene and malnutrition survived and left the hospital alive and well. The older brother with arterial hypertension and normal renal function had a turbulent course, was intubated and eventually died in ICU from sepsis.

The clinical question on outcome of COVID-19 infection in patients on HD remains controversial. The European Renal Association COVID-19 Database collaboration, including 768 dialysis patients, concluded that the 28-d probability of death with COVID-19 in patients on dialysis is high (25% for all patients and 33.5% among those admitted in the hospital) and is associated predominantly with frailty and also with age. Surprisingly none of the known co-morbidities showed statistical significance by multivariate analysis, apart from obesity > 35 kg/m2 BMI and heart failure[5]. The much larger OpenSafely platform concluded that dialysis or ESRD (kidney dialysis around 24.000 patients) was associated with an almost four-fold increased risk of COVID-19 related deaths. Age above 60 years, diabetes and obesity > 35 kg/m2 were also independent risk factors for mortality[6]. Other studies from Spain[8] and United States[9] reported a high COVID-19 related mortality among dialysis patients. In contrast, Naaraayan et al[10] found that patients with ESRD-HD have a milder course of COVID-19 illness. These discrepancies may be in part due to the unique pathogenesis of COVID-19 with two distinct immune responses from the host, as recently described[11], or to differences in the genetic background.

To evaluate the severity of the clinical condition of the siblings at baseline, we measured the total comorbidity burden by the use of Charlson comorbidity index[12]. The index score was 7 for patient 1 and 4 for patient 2, corresponding to an estimated 10-year survival rate of 0% and 53%, respectively. Of note, according to the Clinical Frailty Scale, both brothers had the same high frailty score of 7 on admission[13].

From a laboratory point of view (radiology and blood panel), the HD patient had a better profile from the start, according the data emerged from the general population[14]. He appeared “less inflamed” on admission (Table 1 and Figure 1) with lower WBC, no lymphopenia, lower neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio[15], less CRP and ferritin[16] levels and lower pulmonary CT imaging score. Other positive prognostic markers for the HD patient in the first 5 d of admission were lower lactate dehydrogenase[17] and d-dimers[18] (Figure 1). Of note, both siblings had gastrointestinal bleeding, which has been reported as one of the manifestations of COVID-19 infection[19].

Cardiac troponin was not predictive of outcome, although it has been described as predictive in a study[14], notably with no dialysis patients included. Increased troponin levels in patients with kidney disease may be due to cardiac injury associated with chronic structural heart disease rather than acute ischemia, especially when the levels do not change rapidly over time[20]. Interestingly troponin levels were high from the admission in the HD patient and decreased afterwards. On the contrary, they were low in the non-survivor and started to rise only after intubation and AKI.

The strength of this report is that it involves two brothers with presumably similar genetic background and similar co-morbidities, except for the renal function. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of COVID-19 disease in a family with member(s) maintained on chronic HD.

CONCLUSION

We report the opposite outcome of two diabetic elderly brothers infected simultaneously by COVID-19, in which, despite the odds, the one on HD survived and the other with normal renal function followed the typical severe form and died. The surprising different outcome of these two brothers questions the relevance of HD as an independent risk factor of COVID-19-related death and emphasizes the need for further research.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge the support and contribution in the management of the COVID-19 infected patients of doctors Kalogeropoulou S, Katsoudas S, Gounari P, Nikolopoulos P and Tsotsorou O in the Nephrology Department and doctors Skyllas G, Paramythiotou E and Rizos M in the ICU Department. We would also like to thank Professors Armaganidis A and Dimopoulos G for their support and guidance in the management of the severely infected COVID-19 patients in the ICU.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: All study participants, or their legal guardian, provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment.

Conflict-of-interest statement: No conflict of interest from none of the authors.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: October 1, 2020

First decision: November 12, 2020

Article in press: December 27, 2020

Specialty type: Urology and nephrology

Country/Territory of origin: Greece

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gubensek J S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wang LL

Contributor Information

Dimitra Bacharaki, Department of Nephrology, B Propaideutiki Internal Medicine Clinic, Attikon University Hospital, Chaidari 12064, Greece. bacharaki@gmail.com.

Evangelia Chrysanthopoulou, Intensive Care Unit, Attikon University Hospital, Chaidari 12064, Greece.

Sotiria Grigoropoulou, D Internal Medicine Clinic, Attikon University Hospital, Chaidari 12064, Greece.

Panagiotis Giannakopoulos, Department of Nephrology, B Propaideutiki Internal Medicine Clinic, Attikon University Hospital, Chaidari 12064, Greece.

Panagiotis Simitsis, Intensive Care Unit, Attikon University Hospital, Chaidari 12064, Greece.

Frantzeska Frantzeskaki, Intensive Care Unit, Attikon University Hospital, Chaidari 12064, Greece.

Aikaterini Flevari, Intensive Care Unit, Attikon University Hospital, Chaidari 12064, Greece.

Minas Karagiannis, Department of Nephrology, B Propaideutiki Internal Medicine Clinic, Attikon University Hospital, Chaidari 12064, Greece.

Aggeliki Sardeli, Department of Nephrology, B Propaideutiki Internal Medicine Clinic, Attikon University Hospital, Chaidari 12064, Greece.

Dimitra Kavatha, D Internal Medicine Clinic, Attikon University Hospital, Chaidari 12064, Greece.

Anastasia Antoniadou, D Internal Medicine Clinic, Attikon University Hospital, Chaidari 12064, Greece.

Demetrios Vlahakos, Department of Nephrology, B Propaideutiki Internal Medicine Clinic, Attikon University Hospital, Chaidari 12064, Greece.

References

- 1.Pak A, Adegboye OA, Adekunle AI, Rahman KM, McBryde ES, Eisen DP. Economic Consequences of the COVID-19 Outbreak: the Need for Epidemic Preparedness. Front Public Health. 2020;8:241. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rothan HA, Byrareddy SN. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. J Autoimmun. 2020;109:102433. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kato S, Chmielewski M, Honda H, Pecoits-Filho R, Matsuo S, Yuzawa Y, Tranaeus A, Stenvinkel P, Lindholm B. Aspects of immune dysfunction in end-stage renal disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1526–1533. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00950208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prichard SS. Comorbidities and their impact on outcome in patients with end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 2000;57:100–104. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hilbrands LB, Duivenvoorden R, Vart P, Franssen CFM, Hemmelder MH, Jager KJ, Kieneker LM, Noordzij M, Pena MJ, Vries H, Arroyo D, Covic A, Crespo M, Goffin E, Islam M, Massy ZA, Montero N, Oliveira JP, Roca Muñoz A, Sanchez JE, Sridharan S, Winzeler R, Gansevoort RT ERACODA Collaborators. COVID-19-related mortality in kidney transplant and dialysis patients: results of the ERACODA collaboration. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;35:1973–1983. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfaa261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran K, Bacon S, Bates C, Morton CE, Curtis HJ, Mehrkar A, Evans D, Inglesby P, Cockburn J, McDonald HI, MacKenna B, Tomlinson L, Douglas IJ, Rentsch CT, Mathur R, Wong AYS, Grieve R, Harrison D, Forbes H, Schultze A, Croker R, Parry J, Hester F, Harper S, Perera R, Evans SJW, Smeeth L, Goldacre B. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature. 2020;584:430–436. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2521-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang R, Li X, Liu H, Zhen Y, Zhang X, Xiong Q, Luo Y, Gao C, Zeng W. Chest CT Severity Score: An Imaging Tool for Assessing Severe COVID-19. Radiol Cardiothorac Imag . 2020;2:e200047. doi: 10.1148/ryct.2020200047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goicoechea M, Sánchez Cámara LA, Macías N, Muñoz de Morales A, Rojas ÁG, Bascuñana A, Arroyo D, Vega A, Abad S, Verde E, García Prieto AM, Verdalles Ú, Barbieri D, Delgado AF, Carbayo J, Mijaylova A, Acosta A, Melero R, Tejedor A, Benitez PR, Pérez de José A, Rodriguez Ferrero ML, Anaya F, Rengel M, Barraca D, Luño J, Aragoncillo I. COVID-19: clinical course and outcomes of 36 hemodialysis patients in Spain. Kidney Int. 2020;98:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flythe JE, Assimon MM, Tugman MJ, Chang EH, Gupta S, Shah J, Sosa MA, Renaghan AD, Melamed ML, Wilson FP, Neyra JA, Rashidi A, Boyle SM, Anand S, Christov M, Thomas LF, Edmonston D, Leaf DE STOP-COVID Investigators. Characteristics and Outcomes of Individuals With Pre-existing Kidney Disease and COVID-19 Admitted to Intensive Care Units in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naaraayan A, Nimkar A, Hasan A, Pant S, Durdevic M, Elenius H, Nava Suarez C, Basak P, Lakshmi K, Mandel M, Jesmajian S. End-Stage Renal Disease Patients on Chronic Hemodialysis Fare Better With COVID-19: A Retrospective Cohort Study From the New York Metropolitan Region. Cureus. 2020;12:e10373. doi: 10.7759/cureus.10373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Netea MG, Rovina N, Akinosoglou K, Antoniadou A, Antonakos N, Damoraki G, Gkavogianni T, Adami ME, Katsaounou P, Ntaganou M, Kyriakopoulou M, Dimopoulos G, Koutsodimitropoulos I, Velissaris D, Koufargyris P, Karageorgos A, Katrini K, Lekakis V, Lupse M, Kotsaki A, Renieris G, Theodoulou D, Panou V, Koukaki E, Koulouris N, Gogos C, Koutsoukou A. Complex Immune Dysregulation in COVID-19 Patients with Severe Respiratory Failure. Cell Host Microbe 2020; 27: 992-1000. :e3. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, Bergman H, Hogan DB, McDowell I, Mitnitski A. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. 2005;173:489–495. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Du RH, Liang LR, Yang CQ, Wang W, Cao TZ, Li M, Guo GY, Du J, Zheng CL, Zhu Q, Hu M, Li XY, Peng P, Shi HZ. Predictors of mortality for patients with COVID-19 pneumonia caused by SARS-CoV-2: a prospective cohort study. Eur Respir J. 2020;55 doi: 10.1183/13993003.00524-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Y, Du X, Chen J, Jin Y, Peng L, Wang HHX, Luo M, Chen L, Zhao Y. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as an independent risk factor for mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Infect. 2020;81:e6–e12. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, Xiang J, Wang Y, Song B, Gu X, Guan L, Wei Y, Li H, Wu X, Xu J, Tu S, Zhang Y, Chen H, Cao B. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henry BM, Aggarwal G, Wong J, Benoit S, Vikse J, Plebani M, Lippi G. Lactate dehydrogenase levels predict coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) severity and mortality: A pooled analysis. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38:1722–1726. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.05.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang L, Yan X, Fan Q, Liu H, Liu X, Liu Z, Zhang Z. D-dimer levels on admission to predict in-hospital mortality in patients with Covid-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1324–1329. doi: 10.1111/jth.14859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gulen M, Satar S. Uncommon presentation of COVID-19: Gastrointestinal bleeding. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2020;44:e72–e76. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ellis K, Dreisbach AW, Lertora JL. Plasma elimination of cardiac troponin I in end-stage renal disease. South Med J. 2001;94:993–996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]