Abstract

Rationale: In 2017, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) developed a new surveillance definition of sepsis, the adult sepsis event (ASE), to better track sepsis epidemiology. The ASE requires evidence of acute organ dysfunction and defines baseline organ function pragmatically as the best in-hospital value. This approach may undercount sepsis if new organ dysfunction does not resolve by discharge.

Objectives: To understand how sepsis identification and outcomes differ when using the best laboratory values during hospitalization versus methods that use historical lookbacks to define baseline organ function.

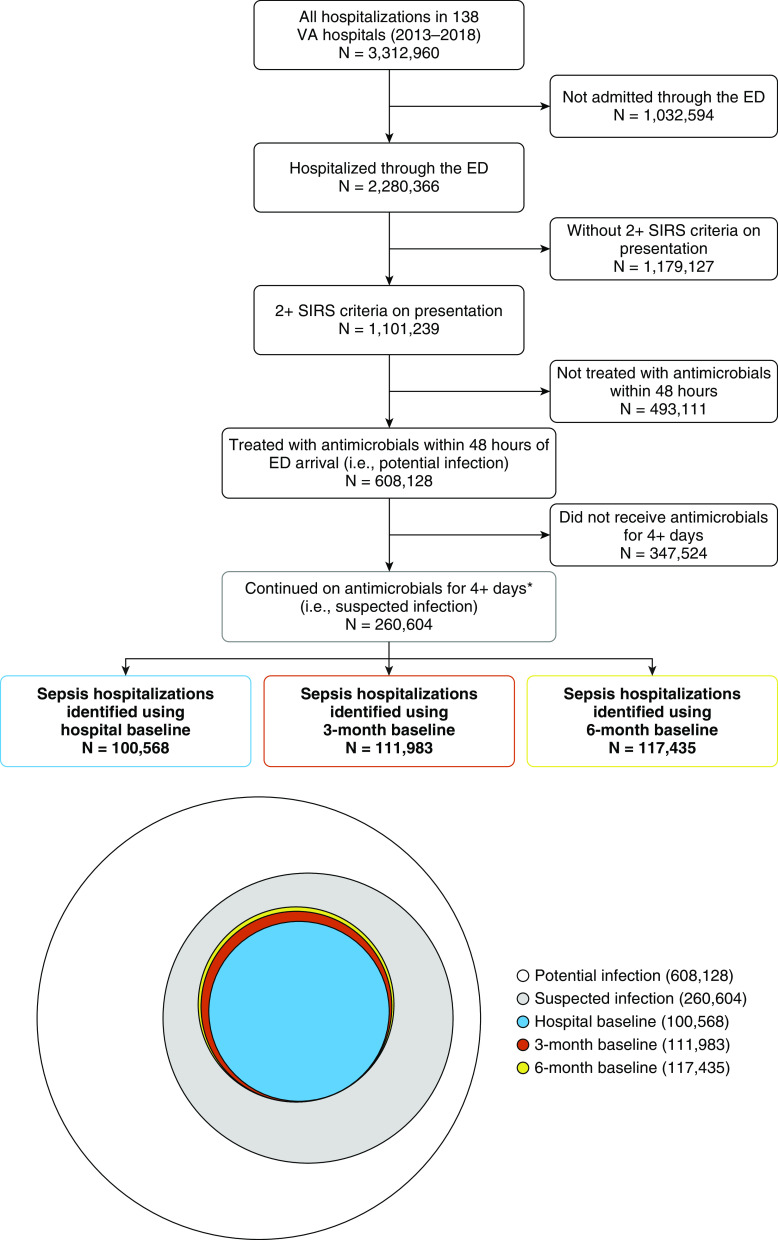

Methods: We identified all patients hospitalized at 138 Veterans Affairs hospitals (2013–2018) admitted via the emergency department with two or more systemic inflammatory response criteria, were treated with antibiotics within 48 hours (i.e., had potential infection), and completed 4+ days of antibiotics (i.e., had suspected infection). We considered the following three approaches to defining baseline renal, hematologic, and liver function: the best values during hospitalization (as in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s ASE), the best values during hospitalization plus the prior 90 days (3-mo baseline), and the best values during hospitalization plus the prior 180 days (6-mo baseline). We determined how many patients met the criteria for sepsis by each approach, and then compared characteristics and outcomes of sepsis hospitalizations between the three approaches.

Results: Among 608,128 hospitalizations with potential infection, 72.1%, 68.5%, and 58.4% had creatinine, platelet, and total bilirubin measured, respectively, in the prior 3 months. A total of 86.0%, 82.6%, and 74.8%, respectively, had these labs in the prior 6 months. Using the hospital baseline, 100,568 hospitalizations met criteria for community-acquired sepsis. By contrast, 111,983 and 117,435 met criteria for sepsis using the 3- and 6-month baselines, for a relative increase of 11% and 17%, respectively. Patient characteristics were similar across the three approaches. In-hospital mortality was 7.2%, 7.0%, and 6.8% for sepsis hospitalizations identified using the hospital, 3-month baseline, and 6-month baseline. The 30-day mortality was 12.5%, 12.7%, and 12.5%, respectively.

Conclusions: Among veterans hospitalized with potential infection, the majority had laboratory values in the prior 6 months. Using 3- and 6-month lookbacks to define baseline organ function resulted in an 11% and 17% relative increase, respectively, in the number of sepsis hospitalizations identified.

Keywords: sepsis, epidemiology, infections, electronic health records

Sepsis, defined as life-threatening organ dysfunction secondary to infection, is a leading cause of death in the United States (1). Recognition and coding of sepsis have increased over time, and these temporal changes may bias measurements of sepsis incidence and outcomes—in particular, the measurement of trends over time (2–5). Studies that identify sepsis using diagnostic codes consistently find an increasing number of sepsis hospitalizations with improving outcomes, which is at least partially explained by greater recognition of less severely ill patients with sepsis over time (6–8).

To track the incidence and outcomes of sepsis more objectively, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) developed a new definition for sepsis surveillance—the adult sepsis event (ASE) (9). This definition leverages electronic health record (EHR) data and requires objective evidence of infection and acute organ dysfunction. This surveillance definition has been used in several studies of U.S. sepsis epidemiology (7, 10–12). In analyses using the CDC’s ASE definition, the incidence and outcomes of sepsis were stable in the United States from 2009 to 2014, in contrast with studies that identified sepsis by diagnostic codes (7).

ASE defines acute organ dysfunction as a change from baseline organ function, in which baseline function is defined pragmatically using the best laboratory values during hospitalization (9). This approach makes it possible to define baseline organ function for all hospitalizations. However, patients with community-acquired sepsis often arrive to the hospital with acute organ dysfunction already present (13–16), and, if the organ dysfunction does not resolve by hospital discharge, then the ASE definition would assume this is chronic organ dysfunction and miss the case of sepsis. It is unclear how this assumption may bias estimates of sepsis using the ASE definition.

We sought to understand the extent to which sepsis identification and outcomes differ when using the best laboratory values during hospitalization (as in CDC’s ASE) versus approaches that incorporate historical laboratory data to define baseline organ function.

Methods

Study Setting

The U.S. Veterans Affairs (VA) healthcare system is an integrated system that provides comprehensive inpatient and outpatient medical care to more than 6–8 million veterans (17–19). The VA uses a single EHR system, which is archived in a central data repository (the Corporate Data Warehouse) to support operations and research (20). The Ann Arbor VA Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Study Cohort

We identified all hospitalizations (21) admitted via the emergency department for potential infection to 138 nationwide VA hospitals (2013–2018). Potential infection was defined as 1) two or more systemic inflammatory response (SIRS) criteria (22) during the 24 hours before emergency department arrival to 48 hours after emergency department arrival and 2) treatment with systemic (intravenous or oral) antimicrobial therapy initiated within 48 hours of emergency department arrival (9). We used SIRS criteria to identify potential infection because these criteria are consistent with host response to infection and commonly used to support a diagnosis of infection in clinical practice. SIRS criteria were the following: 1) abnormal white blood cell count (>12 × 109/L or <4 × 109/L); 2) abnormal body temperature (>38°C or <36°C); 3) heart rate >90 beats/min; 4) respiratory rate >20 breaths/min. Admission through the emergency department was identified in the Emergency Department Information System domain within the Corporate Data Warehouse.

Similar to ASE, patients were considered to have suspected infection if antimicrobial therapy was continued for at least 4 days or the patient died before 4 days and received antimicrobial therapy within 1 day of death. However, in contrast to ASE, we considered antimicrobial therapy prescribed at hospital discharge because we believe it is possible to have sepsis but be hospitalized for less than 4 days. We did not require blood cultures because we deemed 4 days of antibiotics to be sufficient evidence that clinicians believed that infection was present, and some guidelines (e.g., American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for community-acquired pneumonia) recommend “not routinely obtaining blood cultures in adults with community-acquired pneumonia managed in the hospital setting” (23).

Identification of Sepsis

Among the cohort of hospitalizations for suspected infection, we identified community-acquired sepsis using an approach adapted from the CDC’s ASE definition. Specifically, we identified all hospitalizations with at least one acute organ dysfunction during the 24 hours before emergency department arrival through 48 hours after emergency department arrival, including acute renal dysfunction, acute liver dysfunction, acute hematologic dysfunction, lactate ≥2.0 mmol/L, receipt of invasive mechanical ventilation, and receipt of intravenous vasopressors. Acute renal, liver, and hematologic dysfunction required both an abnormal laboratory value and a departure from baseline, as defined below. Acute renal dysfunction was defined as creatinine ≥1.2 mg/dl and a 50% increase from baseline. Patients with preexisting end-stage renal disease, as identified by diagnostic codes, were not eligible to have acute renal dysfunction. Acute liver dysfunction was defined as total bilirubin ≥2.0 mg/dl and a 100% increase from baseline. Acute hematologic dysfunction was defined as a platelet count <100 cells/μl and a 50% decrease from baseline.

Three Approaches to Defining Baseline Organ Function

We considered the following three approaches to defining baseline organ dysfunction: the “best” values (i.e., the lowest creatinine, the lowest total bilirubin, and the highest platelet count) during hospitalization, the best values during hospitalization plus the prior 90 days, and the best values during hospitalization plus the prior 180 days. For simplicity, we will refer to these three approaches as the hospital baseline, the 3-month baseline, and the 6-month baseline. We considered the 24 hours before emergency department arrival as part of the hospitalization because very recent laboratories, even if done elsewhere, are commonly available at emergency department presentation and part of clinical decision-making (24, 25). If anything, this decision would underestimate the impact of incorporating prehospital laboratories.

Analysis and Outcomes

We measured the number (percentage) of hospitalizations with creatinine, total bilirubin, and platelet count in the 3 and 6 months before emergency department presentation. We compared the number (percentage) of hospitalizations defined as having sepsis using the three different approaches to defining baseline organ function. We compared characteristics and outcomes of sepsis hospitalizations identified by the three approaches, specifically the number and types of organ dysfunctions, the length of hospitalization, and the rate of in-hospital and 30-day mortality. Data management and analysis were performed using SQL, SAS (SAS Institute Inc.), and R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, https://www.R-project.org/).

Results

Among 3,312,960 hospitalizations at 138 VA hospitals (2013–2018), 2,280,366 (68.8%) patients presented through the emergency department, of whom 1,101,239 (33.2% of all hospitalizations) had two or more SIRS criteria. Of these 1,101,239 hospitalizations, 608,128 (18.4% of all hospitalizations) were initiated on antimicrobial therapy within 48 hours of arrival to emergency department (i.e., had potential infection), and 260,604 completed 4+ days of antimicrobial therapy or died before 4 days while still on antimicrobials (i.e., had suspected infection) (Figure 1). A total of 207,276 (34.1% of all hospitalizations initiated on antibiotics) patients received 4+ days of antibiotics as an inpatient, 51,158 (8.4%) patients were discharged and completed 4+ days of antibiotics as an outpatient, and 2,170 (0.4%) patients died while receiving antibiotics.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram and a Euler diagram (proportional Venn diagram) showing the relationship between sepsis populations based on different definitions of baseline organ function. There were 3,312,960 hospitalizations from 2013 to 2018, of which 2,280,366 presented through the emergency department (ED). A total of 1,101,239 met two or more systemic inflammatory response (SIRS) criteria during the 24 hours before ED arrival to 48 hours after ED arrival. Of these, there were 608,128 hospitalizations for potential infection (two or more SIRS criteria + treatment with antimicrobial therapy within 48 h of ED arrival) and 260,604 hospitalizations with suspected infection (potential infection + antimicrobial for at least 4 d or patient died before 4 d and received antimicrobial within 1 d of death). Using the “best” hospitalized values for renal, liver, and hematologic function, 100,568 met criteria for sepsis. Using the “best” laboratory values during hospitalization plus the prior 90 days (3-mo baseline) and the “best” laboratory values during hospitalization plus the prior 180 days (6-mo baseline), 111,983 and 117,435 met criteria for sepsis, respectively. VA = Veterans Affairs.

Baseline Laboratory Values

Of the 608,128 hospitalizations with potential infection (Figure 1), prehospital laboratory data was commonly available—72.1% had creatinine, 68.5% had platelet count, and 58.4% had bilirubin measured in the 3 months before hospitalization (Table 1). Eighty-six percent, 82.6%, and 74.8% had creatine, platelet count, and bilirubin measured, respectively, in the 6 months before hospitalization. Patients with laboratory values available from the prior 6 months had a higher prevalence of comorbid conditions (e.g., congestive heart failure, chronic pulmonary disease, diabetes, malignancy, and renal disease; all P < 0.05) than those patients without laboratory values in the prior 6 months (see Table E1 in the online supplement).

Table 1.

Availability of laboratory data in the 3 and 6 months preceding 608,128 hospitalizations for potential infection

| Laboratory | Measured in Prior 3 Mo* [n (% of All Hospitalizations for Potential Infection)] | Measured in Prior 6 Mo* [n (% of All Hospitalizations for Potential Infection)] |

|---|---|---|

| Creatinine | 438,301 (72.1) | 522,862 (86.0) |

| Platelet | 416,555 (68.5) | 502,340 (82.6) |

| Bilirubin | 355,334 (58.4) | 454,919 (74.8) |

Laboratories drawn in the 24 hours before emergency department arrival were considered as part of the hospitalization. Laboratories drawn in the 24 hours to 90 days before emergency department arrival were considered in the 3-month lookback, and laboratories drawn in the 24 hours to 180 days before emergency department arrival were considered in the 6-month lookback.

Most of the measured laboratory values in the lookback periods were normal (Table 2). Among patients with creatinine measured in the 3-month and 6-month lookback periods, 72.9% and 76.4% were normal, respectively. Among patients with platelet count measured, 96.3% and 97.2%, respectively, were ≥100 cells/μl. Among patients with bilirubin measured, 97.6% and 98.4%, respectively, were <2 mg/dl.

Table 2.

Laboratory data for 608,128 hospitalizations for potential infection

| During Hospitalization* | Prior 3 Mo* | Prior 6 Mo* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline renal function† | |||

| Timeframe of lowest creatinine, n (% of all hospitalizations) | 382,432 (62.9) | 126,637 (20.8) | 98,192 (16.1) |

| Patients with abnormal baseline renal function during time period, n (%) | 143,972 (23.7) | 118,980 (27.1) | 123,253 (23.6) |

| Baseline hematologic function‡ | |||

| Timeframe of highest platelet count, n (%) | 335,148 (55.1) | 155,591 (25.6) | 116,126 (19.1) |

| Patients with abnormal hematologic function during time period, n (%) | 26,589 (4.4) | 15,319 (3.7) | 13,840 (2.8) |

| Baseline liver function§ | |||

| Timeframe of lowest bilirubin, n (% of all hospitalizations) | 267,372 (44.0) | 180,814 (29.7) | 117,913 (19.4) |

| Patients with abnormal baseline liver function during time period, n (%) | 19,968 (3.3) | 8,361 (2.4) | 7,068 (1.6) |

Laboratories drawn in the 24 hours before emergency department arrival were considered as part of the hospitalization. Laboratories drawn in the 24 hours to 90 days before emergency department arrival were considered in the 3-month lookback, and laboratories drawn in the 24 hours to 180 days before emergency department arrival were considered in the 6-month lookback.

Abnormal renal function defined as highest creatinine ≥1.2 mg/dl.

Abnormal hematologic function defined as lowest platelet count <100 cells/μl.

Abnormal liver function defined as highest total bilirubin ≥2.0 mg/dl.

The best renal function occurred while hospitalized in 62.9% of patients, during 3-month lookback in 20.8%, and during 6-month lookback in 16.1% of patients. The best platelet count occurred while hospitalized in 55.1% of patients, during 3-month lookback in 25.6%, and during 6-month lookback in 19.1%. The best total bilirubin occurred during the hospitalization in 44.0% of patients, during 3-month lookback in 29.7%, and during 6-month lookback in 19.4%.

Number of Sepsis Hospitalizations and Patient Characteristics

Using the hospital baseline (as in the ASE surveillance definition), 100,568 hospitalizations met criteria for community-acquired sepsis. By contrast, 111,983 and 117,435 hospitalizations met criteria for sepsis using the 3-month and 6-month baselines, respectively (Figure 1). This represents an 11% and 17% relative increase in sepsis hospitalizations when using the 3-month and 6-month baselines, respectively.

Patient characteristics were similar using the three different approaches to defining sepsis (Table 3). The median age was 68 years across all groups (interquartile range, 62–77 yr), 96.4–96.5% were male, and 71.7–72.1% were White. In the sepsis cohorts identified by hospital, 3-month, and 6-month baselines, respectively, 26.4%, 27.3%, and 28.0% had chronic renal disease; 13.2%, 13.9%, and 13.8% had cancer; and 12.4%, 12.6%, and 12.6% had chronic liver disease. Patients with sepsis who had laboratory values assessed in the prior 6 months had a higher burden of comorbidities than those without laboratory values assessed in the prior 6 months (see Table E2).

Table 3.

Characteristics and outcomes of sepsis hospitalizations identified by three different definitions of baseline organ function

| Hospital Baseline* | 3-Mo Baseline* | 6-Mo Baseline* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalizations for sepsis, n | 100,568 | 111,983 | 117,435 |

| Patient characteristics | |||

| Age in yr, median (IQR) | 68 (62–77) | 68 (62–77) | 68 (62–77) |

| Sex, M, % | 96.4 | 96.5 | 96.5 |

| Race, % | |||

| White | 71.7 | 72.0 | 72.1 |

| Black | 20.3 | 20.0 | 20.0 |

| Other | 8.1 | 8.0 | 7.9 |

| Comorbidities†, % | |||

| Congestive heart failure | 23.3 | 23.8 | 24.2 |

| Neurologic disease | 12.5 | 12.0 | 11.7 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 31.6 | 31.7 | 31.9 |

| Liver disease | 12.4 | 12.6 | 12.6 |

| Diabetes without complication | 25.3 | 25.5 | 25.6 |

| Diabetes with complication | 17.9 | 17.8 | 18.0 |

| Any cancer | 13.2 | 13.9 | 13.8 |

| Metastatic cancer | 5.2 | 5.6 | 5.5 |

| Renal disease | 26.4 | 27.3 | 28.0 |

| Acute organ dysfunction‡, n (%) | |||

| Elevated lactate | 55,173 (54.9) | 55,173 (49.3) | 55,173 (47.0) |

| Renal | 54,672 (54.4) | 66,329 (59.2) | 72,148 (61.4) |

| Shock | 12,647 (12.6) | 12,647 (11.3) | 12,647 (10.8) |

| Hepatic | 9,222 (9.2) | 13,459 (12.0) | 15,319 (13.0) |

| Hematologic | 9,162 (9.1) | 14,543 (13.0) | 16,234 (13.8) |

| Respiratory | 7,953 (7.9) | 7,953 (7.1) | 7,953 (6.8) |

| Number of acute organ dysfunctions, n (%) | |||

| One organ dysfunction | 67,468 (67.1) | 72,966 (65.2) | 75,857 (64.6) |

| Two organ dysfunctions | 22,421 (22.3) | 25,952 (23.2) | 27,646 (23.5) |

| Three or more organ dysfunctions | 10,679 (10.6) | 13,065 (11.7) | 13,932 (11.9) |

| Hospitalization characteristics, n (%) | |||

| Treated in ICU | 39,203 (39.0) | 40,873 (36.5) | 41,600 (35.4) |

| Sepsis diagnostic code§ | 41,304 (41.1) | 43,454 (38.8) | 44,374 (37.8) |

| Severe sepsis diagnostic code§ | 19,712 (19.6) | 20,318 (18.1) | 20,534 (17.5) |

| Septic shock diagnostic code§ | 9,649 (9.6) | 9,772 (8.7) | 9,803 (8.3) |

| Outcomes | |||

| Length of stay, median (IQR), d | 7 (5–12) | 7 (5–11) | 7 (5–11) |

| In-hospital mortality, n (%) | 7,243 (7.2) | 7,848 (7.0) | 8,008 (6.8) |

| 30-d mortality, n (%) | 12,570 (12.5) | 14,193 (12.7) | 14,655 (12.5) |

Definition of abbreviations: ICU = intensive care unit; IQR = interquartile range.

Hospital baseline group refers to patients whose baseline organ function was defined using the “best” values during their hospitalization (including values from the 24 h before emergency department arrival). 3-month baseline and 6-month baseline had baseline organ function defined using values from the 24 hours to 90 days before emergency department arrival and 24 hours to 180 days before emergency department arrival, respectively.

Comorbidities are defined using the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index.

Acute organ dysfunction is defined as the following: elevated lactate required lactic acid ≥2.0 mmol/L. renal dysfunction required a creatinine ≥1.2 mg/dl and a 50% increase from baseline, shock required the receipt of intravenous vasopressors, hepatic dysfunction required total bilirubin ≥2.0 mg/dl and a 100% increase from baseline, hematologic dysfunction required platelet count <100 cells/μl and a 50% decrease from baseline, and respiratory dysfunction required the receipt of invasive mechanical ventilation.

Diagnostic code identified using International Classification of Diseases 9 and 10 codes.

Organ Dysfunction and Mortality

Using the 3-month and 6-month baselines to define sepsis identified more patients with acute renal, liver, and hematologic dysfunction than the hospital baseline (Table 3). The number of patients identified as having acute renal injury increased from 54,672 (54.4% of patients meeting sepsis criteria) with the hospital baseline to 66,329 (59.2%) with the 3-month baseline and 72,148 (61.4%) with the 6-month baseline. Likewise, the number of patients identified as having acute liver dysfunction increased from 9,222 (9.2%) to 13,459 (12.0%) and 15,319 (13.0%), respectively. The number identified as having acute hematologic dysfunction increased from 9,162 (9.1%) to 14,543 (13.0%) and 16,234 (13.8%), respectively.

The total number of patients identified as having community-acquired sepsis with single-organ dysfunction increased from 67,468 in the hospital baseline group to 72,966 in the 3-month baseline and 75,857 in the 6-month baseline. However, as a percentage of all sepsis hospitalizations identified, single-organ dysfunction decreased from 67.1% to 65.2% and 64.6%, respectively. Both the total number and percentage of patients with multiorgan dysfunction increased (Table 3).

In-hospital mortality was 7.2%, 7.0%, and 6.8% for sepsis hospitalizations identified using the hospital, 3-month, and 6-month baselines. The 30-day mortality was 12.5%, 12.7%, and 12.5%, respectively. The median hospital length of stay was 7 days for each. In-hospital mortality was similar among patients with sepsis with versus without laboratory values in the prior 6 months (P > 0.05) (see Table E2).

Discussion

In this large national cohort of patients hospitalized with potential infection in an integrated healthcare system over 6 years, three-quarters of patients had creatinine, platelet count, and bilirubin measured during the 6 months preceding hospitalization. Using historical 3- and 6-month laboratory values to measure baseline organ function, we identified an 11% and 17% relative increase, respectively, in the number of cases of community-acquired sepsis compared with using the best laboratory value during hospitalization. Using historical laboratory data to define baseline organ function resulted in a slightly higher proportion of sepsis hospitalizations with multiorgan failure, but patient characteristics and outcomes were otherwise similar across the three approaches.

The major finding of this study is that using laboratories from the prior 3 and 6 months resulted in a greater number of hospitalizations meeting criteria for community-acquired sepsis. This suggests that the CDC’s ASE definition, which uses the best values during hospitalization to define baseline organ dysfunction, may undercount sepsis hospitalizations by approximately 11–17%. The decision to use hospital baseline is reasonable when prior laboratory data are unavailable or difficult to access. However, this study quantifies the potential magnitude of undercounting that may result from this pragmatic approach and the benefit of incorporating longitudinal patient data into sepsis identification. For integrated healthcare systems with ready access to historical laboratory data (e.g., Kaiser Permanente) (26), it is likely preferable to incorporate historical laboratory data to fully capture sepsis hospitalizations.

The second major finding of this study is that both the characteristics and outcomes of sepsis hospitalizations identified via these three approaches were similar. Specifically, hospital length of stay, in-hospital mortality, and 30-day mortality after sepsis were similar across the three approaches. This contrasts with prior work that has shown differences in the characteristics and outcomes of sepsis hospitalizations using different methods to define sepsis (1, 3, 7, 11, 12, 27, 28). For example, studies comparing various claims-based algorithms for identifying sepsis have yielded threefold differences in sepsis incidence (300 to 1,000 per 100,000 people), threefold differences in prevalence (9–32% of ICU admissions with suspected infection), and twofold differences in in-hospital mortality (15–30%) (3). Similarly, studies comparing claims-based algorithms to EHR-based algorithms have found that claims-based algorithms tend to identify an increasing number of sepsis hospitalizations over time, with declining severity of illness, whereas EHR-based identify a more stable population over time (7). However, the number of sepsis hospitalizations identified can still differ across different EHR-based algorithms. For example, the ASE definition identifies a smaller population with greater mortality than algorithms using change in total Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score (11).

Although our study focused on the CDC’s ASE surveillance definition, the issue of defining baseline laboratory values is pertinent to other methods and purposes of sepsis, including real-time sepsis identification for clinical care or trial enrollment using Sepsis-3 or other criteria. Electronic “sepsis sniffers” embedded within EHRs often identify potential sepsis using SIRS criteria, vital signs, elevated lactate, and other laboratory abnormalities (29, 30). Different algorithms have been developed to help alert clinicians that a patient may have sepsis, but these tools have been hampered by high false-positive rates, which can contribute to alarm fatigue and limit their utility (29, 31–34). Incorporating historical laboratory values may reduce the number of false-positive sepsis alarms due to chronic organ dysfunction. Indeed, one electronic surveillance algorithm developed to identify sepsis on the inpatient wards incorporated laboratories from the prior 3 months to establish baseline organ function and performed well compared with the gold standard of physician review (35).

Although historical laboratory data is helpful to understanding patients’ clinical context, the optimal approach to incorporating prior laboratory data for surveillance purposes is unclear. Patients may have progressive but irreversible organ injury leading into hospitalization such that laboratories from the prior 3- or 6-months are no longer an accurate reflection of baseline organ function. Alternative approaches include using the mean value in the prior 3–6 months or the most recent outpatient value. In a study comparing different algorithms for quantifying baseline organ function versus gold-standard consensus determination by a panel of nephrologists, the mean creatinine during Days 7–365 before hospitalization was determined to be the best method (36). In future studies, the optimal approach to measuring baseline laboratory values could be assessed by chart review, as was done for the CDC’s ASE criteria using the hospital baseline (7), to confirm that the additional hospitalizations identified via 3-month or 6-month lookbacks have a similar positive predictive value for physician-adjudicated sepsis as the hospitalizations identified using the hospital baseline. Given the poor sensitivity of International Classification of Diseases, Version 10 (ICD-10) codes for identifying sepsis both within (37) and outside (7) the VA, comparison with ICD-10–identified sepsis would not provide a suitable gold standard.

Our study has some limitations. First, we considered laboratory values from the 24 hours before hospitalization as part of the patient’s hospitalization. We did this because patients are often sent to the emergency department for suspected infection after having blood work obtained (38). As such, these recent laboratory values are often available and are highly relevant to their hospitalization. Their inclusion would, if anything, reduce the impact of including prehospital laboratory values on identifying additional sepsis hospitalizations (39). Second, we defined potential infection on the basis of two or more SIRS criteria and treatment with systemic antimicrobial therapy initiated within 48 hours of emergency department arrival and defined suspected infection on the basis of continuation of antimicrobial therapy for 4+ days. Although there are no universally agreed on criteria to identify infection, we selected these criteria to focus our study on patients who were very likely to have been infected. Our main goal was to understand how different measures of baseline organ function, and not differences in identification of potential infection, impact sepsis identification. The relative trends in identification of sepsis across these approaches are likely to be similar regardless of the specific criteria used to define potential infection, whereas the absolute magnitude of impact may differ. For this reason, we focus on the relative increase (rather than absolute increase) in sepsis hospitalizations identified. Third, we defined acute organ dysfunction on the basis of both absolute and relative changes in laboratory values. We selected thresholds for relative and absolute changes on the basis of the ASE definition and our clinical experience, but others may prefer higher or lower thresholds to define acute organ dysfunction (40, 41). The main focus of our study was not these thresholds per se but how many patients met these thresholds when using the hospital, 3-month, or 6-month baselines. We preferred to have a higher threshold and require both a relative and absolute change in laboratories to avoid overidentification of acute organ dysfunction given the known measurement error in all laboratories (42, 43). Fourth, this study focuses on a surveillance definition of sepsis only, which is not useful for real-time identification of patients given that the definitional criteria require receipt of 4+ days of antimicrobial therapy. In addition, these sepsis definitions are also not usable for cohort studies that compare treatments because they are conditioned upon future events, which would result in a biased sample of patients. This makes it difficult to generalize to real-time clinical decision-making. However, the issue of measuring baseline laboratories is pertinent to other sepsis identification methods used in real time, such as Sepsis-3 criteria.

Conclusions

In this large, national cohort of hospitalizations for potential infection in an integrated healthcare delivery system, three-quarters of patients had creatinine, platelet count, and bilirubin measured in the 6-months before hospitalization. Using a full 6-month lookback to define baseline organ function resulted in a 17% relative increase in the number of sepsis hospitalizations identified, whereas a 3-month lookback resulted in an 11% relative increase. Patient characteristics and outcomes were similar regardless of which approach was used to define baseline organ function. The increased identification of sepsis could have important implications for sepsis surveillance and epidemiology, clinical care, and prognosis for those patients hospitalized with sepsis.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Jack Iwashyna, Wyndy Wiitala, Makoto Jones, and Jenny Burns for all their wisdom and insight regarding Veterans Affairs data over the years.

Footnotes

Supported by 1R01HS026725–01A1 from the Agency for Healthcare Research Quality. V.X.L. was also supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) R35GM128672. This material is the result of work supported with resources and use of facilities at the Ann Arbor Veterans Affairs Medical Centers. The views in this manuscript do not reflect the position or policy of Agency for Healthcare Research Quality, the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs, or the U.S. government.

Author Contributions: V.X.L. and H.C.P. were involved in study design and conception. D.M., X.Q.W., C.K.H., S.S., and H.C.P. were involved in data acquisition. M.T.W., X.Q.W., C.K.H., S.S., and H.C.P. performed data analysis. M.T.W., D.M., C.K.H., and H.C.P. were involved in data interpretation. M.T.W. and H.C.P. drafted the manuscript. M.T.W., D.M., X.Q.W., C.K.H., S.S., V.X.L., and H.C.P. were involved in critical manuscript review. All authors participated in final manuscript revision and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, et al. The third international consensus definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315:801–810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin GS, Mannino DM, Eaton S, Moss M. The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1546–1554. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaieski DF, Edwards JM, Kallan MJ, Carr BG. Benchmarking the incidence and mortality of severe sepsis in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:1167–1174. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827c09f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lagu T, Rothberg MB, Shieh M-S, Pekow PS, Steingrub JS, Lindenauer PK. Hospitalizations, costs, and outcomes of severe sepsis in the United States 2003 to 2007. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:754–761. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232db65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar G, Kumar N, Taneja A, Kaleekal T, Tarima S, McGinley E, et al. Milwaukee Initiative in Critical Care Outcomes Research (MICCOR) Group of Investigators. Nationwide trends of severe sepsis in the 21st century (2000-2007) Chest. 2011;140:1223–1231. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rhee C, Gohil S, Klompas M. Regulatory mandates for sepsis care: reasons for caution. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1673–1676. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1400276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rhee C, Dantes R, Epstein L, Murphy DJ, Seymour CW, Iwashyna TJ, et al. CDC Prevention Epicenter Program. Incidence and trends of sepsis in US hospitals using clinical vs claims data, 2009-2014. JAMA. 2017;318:1241–1249. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.13836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jafarzadeh SR, Thomas BS, Marschall J, Fraser VJ, Gill J, Warren DK. Quantifying the improvement in sepsis diagnosis, documentation, and coding: the marginal causal effect of year of hospitalization on sepsis diagnosis. Ann Epidemiol. 2016;26:66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hospital toolkit for adult sepsis surveillance. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2018 [accessed 2020 Jul 8]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/sepsis/pdfs/Sepsis-Surveillance-Toolkit-Mar-2018_508.pdf.

- 10.Rhee C, Kadri S, Huang SS, Murphy MV, Li L, Platt R, et al. Objective sepsis surveillance using electronic clinical data. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37:163–171. doi: 10.1017/ice.2015.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rhee C, Zhang Z, Kadri SS, Murphy DJ, Martin GS, Overton E, et al. Sepsis surveillance using adult sepsis events simplified eSOFA criteria versus sepsis-3 sequential organ failure assessment criteria. Crit Care Med. 2019;47:307–314. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson AEW, Aboab J, Raffa JD, Pollard TJ, Deliberato RO, Celi LA, et al. A comparative analysis of sepsis identification methods in an electronic database. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:494–499. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mouncey PR, Osborn TM, Power GS, Harrison DA, Sadique MZ, Grieve RD, et al. ProMISe Trial Investigators. Trial of early, goal-directed resuscitation for septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1301–1311. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yealy DM, Kellum JA, Huang DT, Barnato AE, Weissfeld LA, Pike F, et al. ProCESS Investigators. A randomized trial of protocol-based care for early septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1683–1693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1401602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peake SL, Delaney A, Bailey M, Bellomo R, Cameron PA, Cooper DJ, et al. ARISE Investigators; ANZICS Clinical Trials Group. Goal-directed resuscitation for patients with early septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1496–1506. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1404380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schuler A, Wulf DA, Lu Y, Iwashyna TJ, Escobar GJ, Shah NH, et al. The impact of acute organ dysfunction on long-term survival in sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:843–849. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Veterans Health Administration. About VHA - Veterans Health Administration. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2020 [revised 2021 Jan; accessed 2020 Jul 8]. Available from: https://www.va.gov/health/aboutvha.asp.

- 18.National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. VA utilization profile FY. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2017 [accessed 2020 Aug 12]. Available from: https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/Quickfacts/VA_Utilization_Profile_2017.pdf.

- 19.Huang G, Muz B, Kim S, Gasper J.2017 survey of veteran enrollees’ health and use of health care Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2018[accessed 2020 Aug 12]. Available from: https://www.va.gov/HEALTHPOLICYPLANNING/SOE2017/VA_Enrollees_Report_Data_Findings_Report2.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 20.Department of Veterans Affairs. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) 2014 [revised 2014 Mar; accessed 2020 Jul 8]. Available from: https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/vinci/cdw.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vincent BM, Wiitala WL, Burns JA, Iwashyna TJ, Prescott HC. Using veterans affairs corporate data warehouse to identify 30-day hospital readmissions. Health Serv Outcomes Res Methodol. 2018;18:143–154. doi: 10.1007/s10742-018-0178-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, Dellinger RP, Fein AM, Knaus WA, et al. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis: the ACCP/SCCM consensus conference committee: American college of chest physicians/society of critical care medicine. Chest. 1992;101:1644–1655. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.6.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, Anzueto A, Brozek J, Crothers K, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia: an official clinical practice guideline of the American thoracic society and infectious diseases society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200:e45–e67. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201908-1581ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weinick RM, Bristol SJ, DesRoches CM. Urgent care centers in the U.S.: findings from a national survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:79. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siegfried I, Jacobs J, Olympia RP. Adult emergency department referrals from urgent care centers. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37:1949–1954. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2019.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCarthy D, Mueller K, Wrenn J. Kaiser Permanente: bridging the quality divide with integrated practice, group accountability, and health information technology. New York, NY: Commonwealth Fund; 2009 [accessed 2020 Oct 19]. Available from: https://www.sma.sk.ca/kaizen/content/files/2009%20Commonwealth%20Fund%20Kaiser%20Permanente.pdf.

- 27.Rhee C, Murphy MV, Li L, Platt R, Klompas M Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Epicenters Program. Comparison of trends in sepsis incidence and coding using administrative claims versus objective clinical data. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:88–95. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seymour CW, Coopersmith CM, Deutschman CS, Gesten F, Klompas M, Levy M, et al. Application of a framework to assess the usefulness of alternative sepsis criteria. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:e122–e130. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Makam AN, Nguyen OK, Auerbach AD. Diagnostic accuracy and effectiveness of automated electronic sepsis alert systems: a systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2015;10:396–402. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Downing NL, Rolnick J, Poole SF, Hall E, Wessels AJ, Heidenreich P, et al. Electronic health record-based clinical decision support alert for severe sepsis: a randomised evaluation. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28:762–768. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nguyen SQ, Mwakalindile E, Booth JS, Hogan V, Morgan J, Prickett CT, et al. Automated electronic medical record sepsis detection in the emergency department. PeerJ. 2014;2:e343. doi: 10.7717/peerj.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siebig S, Kuhls S, Imhoff M, Gather U, Schölmerich J, Wrede CE. Intensive care unit alarms: how many do we need? Crit Care Med. 2010;38:451–456. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181cb0888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nanji KC, Slight SP, Seger DL, Cho I, Fiskio JM, Redden LM, et al. Overrides of medication-related clinical decision support alerts in outpatients. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21:487–491. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2013-001813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kizzier-Carnahan V, Artis KA, Mohan V, Gold JA. Frequency of passive EHR alerts in the ICU: another form of alert fatigue? J Patient Saf. 2019;15:246–250. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Valik JK, Ward L, Tanushi H, Müllersdorf K, Ternhag A, Aufwerber E, et al. Validation of automated sepsis surveillance based on the Sepsis-3 clinical criteria against physician record review in a general hospital population: observational study using electronic health records data. BMJ Qual Saf. 2020;29:735–745. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2019-010123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siew ED, Ikizler TA, Matheny ME, Shi Y, Schildcrout JS, Danciu I, et al. Estimating baseline kidney function in hospitalized patients with impaired kidney function. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7:712–719. doi: 10.2215/CJN.10821011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prescott HC. Variation in postsepsis readmission patterns: a cohort study of Veterans Affairs beneficiaries. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14:230–237. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201605-398OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu VX, Escobar GJ, Chaudhary R, Prescott HC. Healthcare utilization and Infection in the week prior to sepsis hospitalization. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:513–516. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kipnis P, Turk BJ, Wulf DA, LaGuardia JC, Liu V, Churpek MM, et al. Development and validation of an electronic medical record-based alert score for detection of inpatient deterioration outside the ICU. J Biomed Inform. 2016;64:10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2016.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Siew ED, Matheny ME, Ikizler TA, Lewis JB, Miller RA, Waitman LR, et al. Commonly used surrogates for baseline renal function affect the classification and prognosis of acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2010;77:536–542. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, Molitoris BA, Ronco C, Warnock DG, et al. Acute Kidney Injury Network. Acute Kidney Injury Network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2007;11:R31. doi: 10.1186/cc5713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Joffe M, Hsu CY, Feldman HI, Weir M, Landis JR, Hamm LL Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study Group. Variability of creatinine measurements in clinical laboratories: results from the CRIC study. Am J Nephrol. 2010;31:426–434. doi: 10.1159/000296250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim SY, Kim J-E, Kim HK, Han K-S, Toh CH. Accuracy of platelet counting by automated hematologic analyzers in acute leukemia and disseminated intravascular coagulation: potential effects of platelet activation. Am J Clin Pathol. 2010;134:634–647. doi: 10.1309/AJCP88JYLRCSRXPP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]