Abstract

Background

Trauma is associated with a significant risk of post-trauma complications (PTCs). These include thromboembolic events, strokes, infections, and failure of organ systems (eg, kidney failure). Although care of the trauma patient has evolved during the last decade, whether this has resulted in a reduction in specific PTCs is unknown. We hypothesize that the incidence of PTCs has been decreasing during a 10-year period from 2007 to 2017.

Methods

This is a descriptive study of trauma patients originating from level 1, 2, 3, and 4 trauma centers in the USA, obtained via the Trauma Quality Improvement Program (TQIP) database from 2007 to 2017. PTCs documented throughout the time frame were extracted along with demographic variables. Multiple regression modeling was used to associate admission year with PTCs, while controlling for age, gender, Glasgow Coma Scale score, and Injury Severity Score.

Results

Data from 8 720 026 trauma patients were extracted from the TQIP database. A total of 366 768 patients experienced one or more PTCs. There was a general decrease in the incidence of PTCs during the study period, with the overall incidence dropping from 7.0% in 2007 to 2.8% in 2017. Multiple regression identified a slight decrease in incidence in all PTCs, although deep surgical site infection (SSI), deep venous thrombosis (DVT), and stroke incidences increased when controlled for confounders.

Discussion

Overall the incidence of PTCs dropped during the 10-year study period, although deep SSI, DVT, stroke, and cardiac arrest increased during the study period. Better risk prediction tools, enabling a precision medicine approach, are warranted to identify at-risk patients.

Level of evidence

III.

Keywords: complications, morbidity, multiple trauma, postoperative complications

Introduction

Although major trauma survival rates have improved during the last decades worldwide,1 survivors still face a significant risk of morbidity (post-trauma complications, PTCs). These include thromboembolic events, infections, stroke, organ failure, and sepsis. Previous reports have indicated that almost half of all trauma patients require intensive care unit (ICU) stays, while upwards of 23% of these cases experience a PTC.2 This is thus a significant addition to trauma-related morbidity, further underlined by reports indicating that each hospital complication increases the Odds ratio (OR) for hospital mortality by 2.3.2 For trauma patients admitted to the ICU, a previous study has reported an increase in mortality rate from 10.7% to 16.9% if patients experienced a PTC.2

Previous studies have sought to address both prehospital as well as in-hospital risk factors,3–15 including fielding models for early in-hospital prediction of PTC risk.16 As such, numerous improvements in the care of the injured during the last decade, including adherence to thromboprophylaxis and respiratory protocols, as well as optimal fluid resuscitation strategies, could theoretically translate into a gradual reduction in the incidence of PTCs over time. Whether such reductions can be observed during the last decade is currently unknown and constitutes the primary focus of this study. Despite these improvements in treatment protocols and standards, a number of patients may still be at risk of developing PTCs, owing to factors such as genetic composition, comorbidities, lifestyle choices, and so on. The size of this cohort and thus the scope of the problem of trauma patients unresponsive to current prophylaxis protocols is unknown. Investigating how many patients could potentially benefit from novel, precision medicine-based approaches in PTC prevention presents the secondary aim of this study.

We hypothesized that the incidence of PTCs has reduced during the 10-year study period from 2007 to 2017, but that a number of patients would still suffer these PTCs and thus be potential candidates for future precision medicine-based approaches.

Patients and methods

Access to the Trauma Quality Improvement Program (TQIP) database was granted by the American College of Surgeons TQIP, and data were accessed and handled in line with the TQIP data user agreement. We extracted the PTCs that were available for all years during the study time frame. Online supplemental table 1 lists the chosen 12 PTCs as well as their definitions, as defined by TQIP. We furthermore extracted demographic and injury characteristics variables, including data on age, gender, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), Injury Severity Score (ISS), Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS), disposition on discharge from the emergency department, hospital length of stay (LOS), and time on ventilator. For one variable (pneumonia), values for 2016 and 2017 were excluded due to changes in the underlying data definition compared with previous years. Incidences of the selected PTCs were calculated during the study years.

tsaco-2020-000667supp001.pdf (196.4KB, pdf)

Regression models

To assess whether a significant change in rates of PTCs had occurred, we constructed logistic regression models using the occurrence of the given PTC as the dependent variable, with admission year serving as the predictor. We present univariate model predictions as well as multiple regression modeling, correcting for patients’ age, gender, GCS score, and ISS. Models were furthermore controlled for the presence of traumatic brain injury (TBI, defined as a head AIS score of >2 as previously suggested as a definition for moderate to severe TBI17), early mortality (defined as death in the emergency department), LOS, and time on ventilator.

The rationale for including early mortality and LOS in the model hinged on the fact that early mortality would preclude patients from developing a range of complications, whereas early discharge would mean that the patient was lost to follow-up. Furthermore, the model was controlled for duration of ventilator treatment (where applicable) as this factor is well known to precipitate pulmonary complications.

The selected confounding variables were chosen after appraisal of variables with a perceived significant impact on PTC incidence. Shock-related variables (eg, lactate levels and/or base excess) were assessed but were not consistently available in the data set.

Missing data

From 2007 to 2016, TQIP registered PTCs in a separate complications table, linked to the main table with an identification key. For each trauma entry in the main table, one or more entries exist in the complications table, indication either missing data, no complication or a number of entries corresponding to the number of PTCs recorded. If data were recorded as missing, it was thus not possible to dissect which specific PTC was missing, solely that complication data were missing in total. This approach was changed for the 2017 TQIP data set, where each complication was coded separately. To test the effect of the missing data, a sensitivity analysis was performed. To this end, we created an imputed data set using predictive mean matching as implemented in the R MICE package.18 The regression models were then applied to the imputed data set for comparative purposes.

Data presentation

Data are presented as median (IQR) for continuous variables and percentages for dichotomous variables, where appropriate. Results of regression modeling are presented as OR with 95% CI. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using R.19

Results

A total of 8 720 026 trauma patients were identified during the 10-year study period, with inclusion rates rising from 506 257 in 2007 to 997 970 in 2017. Demographic characteristics and outcomes are summarized in table 1. In summary, 5 402 999 (61.9%) were male, 3 293 987 (37.8%) were female, and 23 040 (0.3%) did not have a registered gender. The median age was 43 (23–64) years. The overall mortality rate was 3.6% (331 956 patients).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical data

| Age, years | 43 (23–64) |

| Male, n (%) | 5 402 999 (62.1) |

| Survivors, n (%) | 8 388 070 (96.2) |

| ISS | 8 (4–10) |

| GCS | 14 (3–15) |

| PTC, n (%) | 366 768 (4.2) |

| Number of PTCs, n (%) | |

| 0 | 8 353 258 (95.8) |

| 1 | 286 252 (3.2) |

| 2 | 58 698 (0.67) |

| 3 | 15 861 (0.18) |

| 4 | 4379 (0.050) |

| 5 | 1161 (0.013) |

| 6 | 327 (0.0038) |

| 7 | 78 (0.00089) |

| 8 | 8 (0.000092) |

| 9 | 3 (0.000034) |

| 11 | 1 (0.000011) |

Data are presented as median (IQR) or percentage where appropriate.

GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; ISS, Injury Severity Score; PTC, post-trauma complication.

A total of 366 768 (4.2%) patients experienced a PTC. Of these, 78% experienced one complication, 16% two complications, and 4.3% three complications, eclipsing eleven PTCs for the most critical cases.

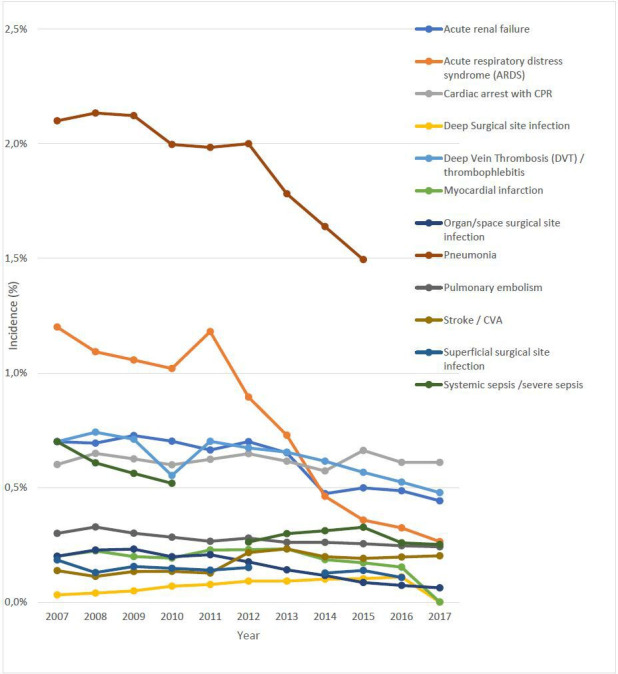

Table 2 lists the incidence of complications throughout the study period, and the development over time is graphically depicted in figure 1. Overall, the incidence of PTC decreased from 7.0% in 2007 to 2.8% in 2017.

Table 2.

Complication categories by year

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

| Patients reported (n) | 506 257 | 633 952 | 684 460 | 721 536 | 783 476 | 830 774 | 827 289 | 858 362 | 912 816 | 963 134 | 997 970 |

| Acute renal failure | 3523 (0.7) | 4568 (0.7) | 5181 (0.7) | 5347 (0.7) | 5479 (0.7) | 5555 (0.7) | 5687 (0.7) | 4249 (0.5) | 4738 (0.5) | 4814 (0.5) | 4411 (0.4) |

| ARDS | 6551 (1.2) | 7198 (1.1) | 7530 (1.1) | 7766 (1.0) | 9743 (1.2) | 7863 (0.9) | 6357 (0.7) | 4146 (0.5) | 3404 (0.4) | 3210 (0.3) | 2634 (0.3) |

| Cardiac arrest with CPR | 2824 (0.6) | 4274 (0.7) | 4453 (0.6) | 4561 (0.6) | 5143 (0.6) | 5694 (0.7) | 5366 (0.6) | 5140 (0.6) | 6295 (0.7) | 6041 (0.6) | 6086 (0.6) |

| Deep SSI | 111 (0.0) | 261 (0.0) | 349 (0.1) | 530 (0.1) | 633 (0.1) | 805 (0.1) | 796 (0.1) | 901 (0.1) | 974 (0.1) | 1090 (0.1) | 882 (0.1) |

| DVT/thrombophlebitis | 3688 (0.7) | 4884 (0.7) | 5068 (0.7) | 4209 (0.6) | 5792 (0.7) | 5913 (0.7) | 5707 (0.7) | 5526 (0.6) | 5386 (0.6) | 5194 (0.5) | 4766 (0.5) |

| Myocardial infarction | 1093 (0.2) | 1471 (0.2) | 1415 (0.2) | 1465 (0.2) | 1879 (0.2) | 2008 (0.2) | 2027 (0.2) | 1663 (0.2) | 1627 (0.2) | 1514 (0.2) | 1449 (0.1) |

| Organ/space SSI | 938 (0.2) | 1163 (0.2) | 1382 (0.2) | 1394 (0.2) | 1352 (0.2) | 2689 (0.2) | 2485 (0.1) | 1139 (0.1) | 1131 (0.1) | 798 (0.1) | 788 (0.1) |

| Pneumonia | 10 827 (2.1) | 14 062 (2.1) | 15 133 (2.1) | 15 211 (2.0) | 16 379 (2.0) | 16 909 (2.0) | 15 547 (1.8) | 14 717 (1.6) | 14 214 (1.5) | N/A | N/A |

| PE | 1492 (0.3) | 2160 (0.3) | 2141 (0.3) | 2157 (0.3) | 2191 (0.3) | 2457 (0.3) | 2276 (0.3) | 2341 (0.3) | 2422 (0.3) | 2440 (0.2) | 2409 (0.2) |

| Stroke/CVA | 483 (0.1) | 737 (0.1) | 953 (0.1) | 1019 (0.1) | 1049 (0.1) | 1898 (0.2) | 2026 (0.2) | 1778 (0.2) | 1817 (0.2) | 1948 (0.2) | 2016 (0.2) |

| Superficial SSI | 647 (0.2) | 849 (0.1) | 1109 (0.2) | 1124 (0.1) | 1153 (0.1) | 1324 (0.2) | N/A | 1138 (0.1) | 1314 (0.1) | 1065 (0.1) | 776 (0.1) |

| Systemic sepsis | 3489 (0.7) | 4004 (0.6) | 4003 (0.6) | 3950 (0.5) | N/A | 2305 (0.3) | 2603 (0.3) | 2797 (0.3) | 3109 (0.3) | 2564 (0.3) | 2507 (0.3) |

Numbers indicate the total number of patients for the year in question (incidence %).

Pneumonia was not included for 2016 and 2017 due to changes in data definition.

Data on superficial SSI and sepsis were not available for years 2013 and 2011, respectively.

ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; DVT, deep venous thrombosis; N/A, not available; PE, pulmonary embolism; SSI, surgical site infection.

Figure 1.

Graphical overview of the development of post-trauma complications from 2007 to 2017. CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; CVA, cerebrovascular accident.

When assessing unadjusted incidence rates, the most common complication throughout all years was pneumonia, with an incidence of between 2.1% in 2007 and 1.5% in 2015 of PTCs (table 2). Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) declined from an incidence of 1.2% to 0.3%, deep venous thrombosis (DVT)/thrombophlebitis from 0.7% to 0.5%, acute renal failure from 0.7% to 0.4%, cardiac arrest unchanged from 0.6% to 0.6%, superficial surgical site infection (SSI) from 0.2% to 0.1%, and sepsis from 0.7% to 0.3%. In contrast, stroke saw a general increase in incidence through the entire period, from 0.1% in 2007 to 0.2% in 2017.

Regression models

The results of the regression models are shown in table 3. Multivariate modeling confirmed a significant decrease over time for PTCs, including acute renal failure (OR 0.97, CI 0.96 to 0.97), ARDS (OR 0.88, CI 0.88 to 0.89), myocardial infarction (OR 0.97, CI 0.97 to 0.98), cardiac arrest (OR 0.89, CI 0.88 to 0.89), organ space infection (OR 0.97, CI 0.97 to 0.98), pneumonia (OR 0.97, CI 0.97 to 0.98), superficial SSI (OR 0.97, CI 0.97 to 0.97), and systemic sepsis (OR 0.67, CI 0.67 to 0.68). In contrast, a significant increase over time in PTCs including deep SSI (OR 1.08, CI 1.07 to 1.10), DVT/thrombophlebitis (OR 1.09, CI 1.08 to 1.09), and stroke (OR 1.05, CI 1.05 to 1.06) was identified.

Table 3.

Results of regression model using the complication in question as the dependent variable and the admission year as the predictor

| Corrected model | Univariate model | |||||

| OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Acute renal failure | 0.97 | 0.96 to 0.97 | <0.01 | 0.93 | 0.93 to 0.94 | <0.01 |

| ARDS | 0.89 | 0.88 to 0.89 | <0.01 | 0.85 | 0.84 to 0.85 | <0.01 |

| Cardiac arrest with CPR | 0.89 | 0.88 to 0.89 | <0.01 | 0.99 | 0.99 to 0.99 | <0.01 |

| Deep SSI | 1.08 | 1.07 to 1.10 | <0.01 | 1.09 | 1.08 to 1.10 | <0.01 |

| DVT/thrombophlebitis | 1.09 | 1.08 to 1.09 | <0.01 | 0.96 | 0.96 to 0.96 | <0.01 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0.97 | 0.97 to 0.98 | <0.01 | 0.95 | 0.94 to 0.95 | <0.01 |

| Organ/space SSI | 0.97 | 0.97 to 0.98 | <0.01 | 0.87 | 0.86 to 0.87 | <0.01 |

| Pneumonia | 0.97 | 0.97 to 0.98 | <0.01 | 0.86 | 0.86 to 0.87 | <0.01 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0.97 | 0.96 to 0.97 | <0.01 | 0.96 | 0.95 to 0.96 | <0.01 |

| Stroke/CVA | 1.01 | 1.01 to 1.02 | <0.01 | 1.04 | 1.04 to 1.05 | <0.01 |

| Superficial SSI | 0.97 | 0.97 to 0.97 | <0.01 | 0.95 | 0.94 to 0.95 | <0.01 |

| Systemic sepsis | 0.67 | 0.67 to 0.68 | <0.01 | 0.71 | 0.70 to 0.72 | <0.01 |

Data are presented as OR with 95% CI and p values.

The multivariate model was controlled for confounders, including age, gender, injury severity, and Glasgow Coma Scale scores.

ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; DVT, deep venous thrombosis; SSI, surgical site infection.

Missing data

Online supplemental table 2 provides an overview of the missing data. Overall, 5.8% of records had one or more variables missing. Online supplemental table 3 lists the results of the regression models when applied to the imputed data set. Although ORs differed between the raw and imputed data sets (table 3 and online supplemental table 3), the directionality of these did not differ. As such, sensitivity analysis did not indicate a substantial impact of the missing data on the regression model results.

Discussion

In this study, we assessed the development of PTCs in the USA during a 10-year period from 2007 to 2017. We hypothesized that temporal PTC incidences would have dropped during the investigative time frame, but that a number of patients remain at risk. Of the 12 selected PTC categories, we did indeed identify significant reductions in the PTC incidence of acute renal failure, ARDS, myocardial infarction, organ space and superficial SSI, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, cardiac arrest, and sepsis. In contrast, the incidence of deep SSI, DVT, and stroke increased over time when multivariate modeling was considered. Although the graphical representation in figure 1 suggests an overall drop in PTC incidence, multivariate modeling thus indicates a slight increase in certain PTCs, which runs counter to the study hypothesis.

In the last study year, where treatment protocols would presumably be optimal compared with the previous years, 27 943 (2.8%) patients experienced one or more PTCs. To put this number into perspective, the global burden of injury in the 2017 study estimated that 520 million patients worldwide suffered traumatic injuries in that year.20 If numbers can be extrapolated, this would mean that an excess of 14 million patients could have suffered a PTC globally in 2017 alone. Although these numbers should be interpreted in the light of the many differences in trauma systems worldwide, they still suggest that a sizeable number of patients remain unresponsive to current prophylaxis protocols and could potentially benefit from precision medicine-based approaches.

Several factors should be considered when interpreting the data, and caution should be exercised when interpreting the presented results. The annual volume of trauma patients in the TQIP data set increased from 2007 (506 257) to 2017 (997 970), and the underlying demographics and injury characteristics also varied over the years. The fluctuations in complication rates could thus in part be due to data from additional trauma centers with demographic and injury characteristics variations being added to the data set. As treatment protocol adjustment after feedback from the TQIP would take time to implement, the rapid increase in the number of participating centers may thus create a setting where centers would enter TQIP with suboptimal PTC incidence rates, which would be gradually corrected once TQIP feedback was obtained and time for protocol optimization was allowed for. Furthermore, as is the case for many retrospective databases, there is likely a significant issue of under-reporting in the data set. As such, a recent study from Japan, investigating 184 214 patients, reported a PTC rate of 12.8%,21 as opposed to 2.8% in this study. Although obvious differences in number and definitions of reported PTC exist between data sets, the presented results should be interpreted in light of the underlying data set. Although TQIP likely also suffers from under-reporting, it is less clear whether such an under-reporting should exhibit a temporal trend. As such, it is likely that the findings of a relatively stable PTC trend for most complications reflect reality, although at a higher incidence than reported here.

Also, the results should be interpreted in the light of the inherent variance in reporting standards between sites this and most other retrospective quality registers suffer from. Indeed, studies have indicated that a degree of interobserver variability exists in TQIP, which could affect the presented results.22

The observed reduction in the incidence of pulmonary complications, including ARDS and pneumonia, can likely be associated with the development and adherence to resuscitation and ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) protocols during the last decade, including outcomes of research collaboratives such as the ARDS Network.23 High incidences of pneumonia are well documented as a major cause of PTC,2 and VAP continues to be a preventable burden for critically ill patients. Studies on prevention strategies have shown variable success, focusing on treatments including non-invasive positive pressure ventilation, optimal bed position, better oral care, and removal of subglottic secretions.24 25 Hospitals adhering to ventilator optimization strategies have reported good drops in incidence statistics.26

ARDS incidences are likely also affected by developments in resuscitation strategies, as well as accelerated patient mobilization efforts.27 As such, the gradual shift from large-volume crystalloid resuscitation toward a permissive hypotensive and balanced blood transfusion regimen has likely played a role in reducing ARDS incidences28–30 nationwide.

Acute renal failure, associated with increased morbidity and mortality as well as hospital LOS,31 also exhibited reduced incidence during the study period. This is likely associated with the development of and adherence to risk assessment protocols targeting renal failure, mainly through optimizing renal perfusion.32 Of note, the second most common reason for renal failure is sepsis, which also exhibited reduced incidence during the study period.

Collectively, it is likely that these improvements are due to increased adherence to updated resuscitation and treatment protocols, including sepsis, as well as resuscitation and treatment guidelines such as those championed by trauma societies.33 34

For thrombosis ORs, we observed a decrease in pulmonary embolism, but a slight increase in DVT and stroke ORs over time when multivariate modeling was considered. Although thrombosis prophylaxis protocols have received much attention,35 with an apparent drop in unadjusted DVT rates over time, multivariate modeling suggested that this could be due to changes in the underlying demographics and trauma characteristics of included patients. As such, current prophylaxis protocols have been unsuccessful in further reducing DVT and stroke incidences over time when patient covariates are considered, thus highlighting a focus area for further research and development.

Although myocardial infarction and cardiac arrest incidence rates decreased in this study, the observed trend for DVT and stroke thus mirrors the rise in cardiovascular disease-related mortality in the general US population during the last decade36 and could potentially be related to changes in lifestyle factors, including diet, smoking, and a general increase in sedentary lifestyle.36 For DVT, the observed increase in adjusted incidence is in line with a general embolism-associated mortality increase in USA since 2008.37 38 Interestingly, this did not translate into an increased incidence of pulmonary embolism in this study, which could potentially be associated with focus on vena cava filters in high-risk patients,39 although this cannot be concluded from these data.

For infectious complications, we observed a reduction in ORs of organ space and superficial SSI, although an increase in deep SSI OR was observed concurrently. Whether this represents real fluctuations associated with changes in treatment strategies (eg, increase in non-operative management strategies) or simply a shift in SSI classification practices cannot be readily deduced from these data. Incidences of SSI have in other studies decreased and were largely associated with small bowel and vascular bypass surgery.40 41 The reduction in SSI incidence observed here is thus in line with previous reports from non-trauma surgical patients. These results should, however, be interpreted with caution. The structure of the TQIP database did not allow for a consistent registration of the nature, indication, and type of surgical procedures. As such, fluctuations in the number of major surgical procedures performed during the investigative time frame could have impacted on the results.

Overall, although selected PTC incidences have shown a temporal decrease (pneumonia and ARDS), other PTCs have failed to show a clear development. Although these exhibited slight increases or reductions, it is questionable whether the magnitude of these fluctuations is of clinical relevance (figure 1). Furthermore, although most of these alterations are statistically significant, this should be analyzed in light of the large number of patients present for analysis.

The study has several limitations. First, this is a retrospective study dependent on the quality and correctness of data sources from the TQIP database. As such, PTCs may have been missed by the curators. Second, although we have sought to control for relevant confounders, the results may still be affected by factors not included in the regression model. Such factors could potentially include the number of major surgical procedures performed, as this could have impacted on PTC incidences, specifically Venous Thromboembolisms (VTE) and SSI rates. Third, data from the TQIP database are limited to trauma centers participating in the program, which may not completely mirror other centers throughout the USA or elsewhere. Fourth, although the sensitivity analysis did not indicate a major effect of the missing data, interpretation of the presented results should be seen in light of the fact that TQIP data quality and data completeness generally increased toward the final years of the study period. The increase in the number of participating hospitals could also have affected data quality as well as reported outcomes, either due to variations in data definitions or differential outcomes between participating centers. It would thus have been interesting to identify hospitals present in TQIP throughout the study time frame to assess PTC variations in these. TQIP, does, however, not allow for an identification of the individual center, which precludes us from making this analysis. Also, the use of advanced directives could have impacted on the level of treatment offered to patients. The TQIP data set does, however, only contain information on such decisions from 2013 and onwards, which was considered incompatible with the analysis approach.

The TQIP data structure was changed during the study period, with the number and types of PTCs recorded differing from 2007 to 2017. Ideally, a uniform data set would have been optimal, and fluctuations in data definitions and recorded variables could thus impact on the results. The TQIP data set adheres to the definition standard set forth by the National Trauma Data Bank, as defined in the National Trauma Data Set (NTDS) standards. There are annual updates of the PTC definitions, and variations could thus affect the presented results. A review of the NTDS changelogs did, however, reflect minor changes with perceived limited impact on the presented findings. For comparative purposes, we provide an overview of the 2007 vs 2017 PTC definitions in online supplemental table 1.

Finally, certain PTCs such as venous embolisms are critically dependent on imaging studies for their detection. The TQIP data set does not allow for an assessment of the use of imaging modalities. As such, whether changes in the frequency of imaging studies could have impacted on the presented findings cannot be deduced from these data but may impact on the results. Collectively, interpretation of the presented results should thus be done with these limitations in mind.

Even with these limitations, we conclude that incidences of PTC remain largely stationary over time, with a slight decrease or increase for selected PTCs. A number of patients remain unresponsive to current treatment prophylaxis and could be candidates for future precision medicine-based approaches.

Footnotes

Contributors: MS and AB conceived the study. AB and RKJ performed data extraction and analyses work. MS, AB and RKJ prepared the article. All authors have approved the final version of the article.

Funding: The study was funded by a grant from the Novo Nordisk Foundation (grant #NNF19OC0055183) to MS.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Requirements for local IRB approval for handling the de-identified TQIP data set were waived according to Danish law.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. Data are available upon submission of a research proposal to the TQIP administrators.

References

- 1.van Breugel JMM, Niemeyer MJS, Houwert RM, Groenwold RHH, Leenen LPH, van Wessem KJP. Global changes in mortality rates in polytrauma patients admitted to the ICU-a systematic review. World J Emerg Surg 2020;15:55. 10.1186/s13017-020-00330-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prin M, Li G, Meghan Prin GL. Complications and in-hospital mortality in trauma patients treated in intensive care units in the United States, 2013. Inj Epidemiol 2016;3:18. 10.1186/s40621-016-0084-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McQueen C, Smyth M, Fisher J, Perkins G. Does the use of dedicated dispatch criteria by emergency medical services optimise appropriate allocation of advanced care resources in cases of high severity trauma? A systematic review. Injury 2015;46:1197–206. 10.1016/j.injury.2015.03.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nathens AB, Jurkovich GJ, Rivara FP, Maier RV. Effectiveness of state trauma systems in reducing injury-related mortality: a national evaluation. J Trauma 2000;48:25–30. discussion -1. 10.1097/00005373-200001000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams T, Finn J, Fatovich D, Jacobs I. Outcomes of different health care contexts for direct transport to a trauma center versus initial secondary center care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prehosp Emerg Care 2013;17:442–57. 10.3109/10903127.2013.804137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brink O, Borris LC, Hougaard K. Effective treatment at a Danish trauma centre. Dan Med J 2012;59:A4393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Celso B, Tepas J, Langland-Orban B, Pracht E, Papa L, Lottenberg L, Flint L. A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing outcome of severely injured patients treated in trauma centers following the establishment of trauma systems. J Trauma 2006;60:371–8. 10.1097/01.ta.0000197916.99629.eb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McNeill G, Bryden D. Do either early warning systems or emergency response teams improve Hospital patient survival? A systematic review. Resuscitation 2013;84:1652–67. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gunning AC, Lansink KWW, van Wessem KJP, Balogh ZJ, Rivara FP, Maier RV, Leenen LPH. Demographic patterns and outcomes of patients in level I trauma centers in three international trauma systems. World J Surg 2015;39:2677–84. 10.1007/s00268-015-3162-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hasler RM, Srivastava D, Aghayev E, Keel MJ, Exadaktylos AK, Schnüriger B. First results from a Swiss level I trauma centre participating in the UK trauma audit and research network (TARN): prospective cohort study. Swiss Med Wkly 2014;144:w13910. 10.4414/smw.2014.13910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kristiansen T, Ringdal KG, Skotheimsvik T, Salthammer HK, Gaarder C, Naess PA, Lossius HM. Implementation of recommended trauma system criteria in south-eastern Norway: a cross-sectional Hospital survey. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2012;20:5. 10.1186/1757-7241-20-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lansink KWW, Leenen LPH. Do designated trauma systems improve outcome? Curr Opin Crit Care 2007;13:686–90. 10.1097/MCC.0b013e3282f1e7a4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mackersie RC. Field triage, and the fragile supply of "optimal resources" for the care of the injured patient. Prehosp Emerg Care 2006;10:347–50. 10.1080/10903120600728920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nathens AB, Jurkovich GJ, Maier RV, Grossman DC, MacKenzie EJ, Moore M, Rivara FP. Relationship between trauma center volume and outcomes. JAMA 2001;285:1164–71. 10.1001/jama.285.9.1164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stawicki SP, Habeeb K, Martin ND, O'Mara MS, Cipolla J, Evans DC, Boulger C, Sarani B, Cook CH, Gupta A, et al. A seven-center examination of the relationship between monthly volume and mortality in trauma: a hypothesis-generating study. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2019;45:281–8. 10.1007/s00068-018-0904-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halvachizadeh S, Baradaran L, Cinelli P, Pfeifer R, Sprengel K, Pape H-C. How to detect a polytrauma patient at risk of complications: a validation and database analysis of four published scales. PLoS One 2020;15:e0228082. 10.1371/journal.pone.0228082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Savitsky B, Givon A, Rozenfeld M, Radomislensky I, Peleg K. Traumatic brain injury: it is all about definition. Brain Inj 2016;30:1194–200. 10.1080/02699052.2016.1187290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Z. Multiple imputation with multivariate imputation by chained equation (mice) package. Ann Transl Med 2016;4:30. 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2015.12.63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.RCT . R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 20.James SL, Castle CD, Dingels ZV, Fox JT, Hamilton EB, Liu Z, S Roberts NL, Sylte DO, Henry NJ, LeGrand KE, et al. Global injury morbidity and mortality from 1990 to 2017: results from the global burden of disease study 2017. Inj Prev 2020;26:i96–114. 10.1136/injuryprev-2019-043494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abe T, Komori A, Shiraishi A, Sugiyama T, Iriyama H, Kainoh T, Saitoh D. Trauma complications and in-hospital mortality: failure-to-rescue. Crit Care 2020;24:223. 10.1186/s13054-020-02951-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arabian SS, Marcus M, Captain K, Pomphrey M, Breeze J, Wolfe J, Bugaev N, Rabinovici R. Variability in interhospital trauma data coding and scoring: a challenge to the accuracy of aggregated trauma registries. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2015;79:359–63. 10.1097/TA.0000000000000788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson BT, Bernard GR. Ards network (NHLBI) studies: successes and challenges in ARDS clinical research. Crit Care Clin 2011;27:459–68. 10.1016/j.ccc.2011.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keyt H, Faverio P, Restrepo MI, PFaMlR HK. Prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia in the intensive care unit: a review of the clinically relevant recent advancements. Indian J Med Res 2014;139:814–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boltey E, Yakusheva O, Costa DK. 5 nursing strategies to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia. Am Nurse Today 2017;12:42–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hilary Babcock M M, Garrison T, Trocillion E, Jones M, Victoria J F, Kollef MH. Chest the cardiopulmonary and critical care Journal. 2005.

- 27.Dittmer DK, Teasell R. Complications of immobilization and bed rest. Part 1: musculoskeletal and cardiovascular complications. Can Fam Physician 1993;39:1428–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kasotakis G, Sideris A, Yang Y, de Moya M, Alam H, King DR, Tompkins R, Velmahos G,. Inflammation and Host Response to Injury Investigators . Aggressive early crystalloid resuscitation adversely affects outcomes in adult blunt trauma patients: an analysis of the glue grant database. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2013;74:1215–21. 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182826e13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bickell WH, Wall MJ, Pepe PE, Martin RR, Ginger VF, Allen MK, Mattox KL. Immediate versus delayed fluid resuscitation for hypotensive patients with penetrating torso injuries. N Engl J Med 1994;331:1105–9. 10.1056/NEJM199410273311701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johansson PI. Goal-directed hemostatic resuscitation for massively bleeding patients: the Copenhagen concept. Transfus Apher Sci 2010;43:401–5. 10.1016/j.transci.2010.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perkins ZB, Captur G, Bird R, Gleeson L, Singer B, O'Brien B. Trauma induced acute kidney injury. PLoS One 2019;14:e0211001. 10.1371/journal.pone.0211001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harty J. Prevention and management of acute kidney injury: UMJ, Ulster Medical Society, 2014. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cannon JW, Khan MA, Raja AS, Cohen MJ, Como JJ, Cotton BA, Dubose JJ, Fox EE, Inaba K, Rodriguez CJ, et al. Damage control resuscitation in patients with severe traumatic hemorrhage. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2017;82:605–17. 10.1097/TA.0000000000001333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin MJ, Brown CVR, Shatz DV, Alam H, Brasel K, Hauser CJ, de Moya M, Moore EE, Vercruysse G, Inaba K. Evaluation and management of abdominal gunshot wounds: a Western trauma association critical decisions algorithm. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2019;87:1220–7. 10.1097/TA.0000000000002410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schünemann HJ, Cushman M, Burnett AE, Kahn SR, Beyer-Westendorf J, Spencer FA, Rezende SM, Zakai NA, Bauer KA, Dentali F, et al. American Society of hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: prophylaxis for hospitalized and nonhospitalized medical patients. Blood Adv 2018;2:3198–225. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018022954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Virani SS, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Delling FN, et al. Heart disease and stroke Statistics-2020 update: a report from the American heart association. Circulation 2020;141:e139–596. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laura Williamson A. After years of decline death rate from lung clots on the rise, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 38.prevention Ccfdca . Data and statistics on venous thromboembolism, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ho KM, Rao S, Honeybul S, Zellweger R, Wibrow B, Lipman J, Holley A, Kop A, Geelhoed E, Corcoran T, et al. A multicenter trial of vena cava filters in severely injured patients. N Engl J Med 2019;381:328–37. 10.1056/NEJMoa1806515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arthur Baker W W, Durkin MJ, Weber DJ, Lewis SS, Moehring RW, Chen LF, Sexton DJ, Anderson DJ. Epidemiology of surgical site infection in a community hospital network: HHS Public Access, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mu Y, Edwards JR, Horan TC, Berrios-Torres SI, Fridkin SK. Improving risk-adjusted measures of surgical site infection for the National healthcare safely network. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2011;32:970–86. 10.1086/662016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

tsaco-2020-000667supp001.pdf (196.4KB, pdf)