Abstract

Background

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are widely used in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), but recent studies have raised doubts whether all COPD patients will benefit from ICS. This study evaluates in a real-life setting the effects of ICS withdrawal in patients with COPD.

Methods

The study was a prospective intervention study following patients with COPD for 6 months after abrupt withdrawal of ICS. FEV1 (L), blood eosinophilic count (x10E9/L) and number of exacerbations were measured at baseline, 1, 3 and 6 months after ICS withdrawal.

Results

Ninety-six patients (56 females (57.4%), mean age 70 years (51–94 years)) with COPD were included in the study. Eleven patients were excluded during the study period (7 patients died, 4 patients withdrew their consent during the study period). During the 6 months, 51 patients (60%) had resumed treatment with ICS, of whom 34 patients (68%) experienced an exacerbation during follow-up. No significant decline in FEV1 was seen in this group between baseline and after 6 months (ΔFEV1 0.07 L, p = 0.09). In the remaining 34 patients (40%) without ICS after 6 months of follow-up, 15 patients (44.1%) experienced an exacerbation. No significant decline was seen in FEV1 at baseline and after 6 months (ΔFEV1 0.04 L, p = 0.28). There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in age (70.5 vs 69.6 years, p = 0.53), nor between FEV1 at baseline (0.96 L vs 1.00 L, p = 0.63) or eosinophilic count (0.25 x10E9/L vs 0.17 x10E9/L, p = 0.07).

Conclusion

Abrupt withdrawal of ICS was possible in some patients. However, more than half of the patients resumed ICS during follow-up. Based on results from our study we were not able to foresee – from neither history of exacerbations nor eosinophilic count – whom will be able to manage without ICS and who will resume treatment with ICS.

Keywords: COPD, inhaled corticosteroids, withdrawal, real-life setting

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a progressive chronic disease in which airway inflammation plays an important role in the pathogenesis of the disease. Frequent symptoms include dyspnea, chronic cough, and sputum production.1,2 Inhalation treatment of patients with COPD has been shown to reduce symptoms and exacerbations, and consists primarily of 3 classes of medications, beta-2 agonists, antimuscarinic drugs, and inhaled corticosteroids, either alone or in combinations.1

However, as COPD has different phenotypes, eg, frequent exacerbators, high eosinophilic count, and coexistence with asthma,3,4 not all patients should be treated the same.5 Especially the use of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) is much debated because of several potential adverse effects, such as increased risk of pneumonia, poor diabetes control, oral candidiasis, increased risk of osteoporosis and benign fractures and cataract.6–13 In 2016, results from the FLAME study showed that combination treatment with long-acting beta-2 agonists and long-acting antimuscarinic drugs (LABA/LAMA) was superior to the combination LABA/ICS in preventing COPD exacerbations in patients with a history of exacerbations during the previous year.14 According to current GOLD 2020 report, ICS should only be considered in patients with ≥2 exacerbations/year, blood eosinophils >300 cells/µL and/or concomitant asthma, and should not be given to patients with repeated pneumonia and blood eosinophils <100 cells/µL.1

However, for several reasons many patients with COPD without the abovementioned criteria are treated with ICS anyway.11,15 Based on GOLD recommendations for withdrawal of ICS in patients with COPD not meeting the criteria, several studies have evaluated the effect of withdrawal from ICS in patients with COPD and found no differences in number of exacerbations or changes in lung function compared to patients continuing ICS.16–19 Contrary to most study populations, many of the COPD patients in real life have been treated with ICS for a long period with an expectation of beneficial effect and thus it may be difficult to stop treatment from one day to another. We hypothesized that ICS withdrawal would be possible yet problematic in patients with COPD. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to follow patients with COPD for 6 months after abrupt withdrawal of ICS with the purpose of evaluating the consequences of withdrawal and the patients’ ability to avoid ICS.

Methods

Settings and Study Population

The current study was conducted using data from the pulmonary outpatient clinic at Little Belt Hospital, Denmark. The study was a prospective intervention study following consecutive patients with COPD for 6 months after abrupt withdrawal of ICS. Baseline data were collected from January to November 2017 and follow-up data were conducted in the following 6 months from study entry. Subjects were followed for 6 months from study entry or until death or lost to follow-up, whichever came first.

To be included in the study, patients should be diagnosed with COPD and treated with one of the following types of ICS for more than 6 months: fluticasone, budesonide or beclomethasone. Daily dose for all patients was calculated and converted to match the dose of budesonide. Mean daily dose was equivalent to 740 µg of budesonide. Additionally, all patients should be treated with LABA and LAMA prior to inclusion as well as throughout the entire study period. When ICS was withdrawn, patients continued using their LABA/LAMA inhalator device. If patients were treated with a combined inhalator containing ICS, they were changed to a similar device without ICS to ensure the same inhalator technique.

Only patients who had already been diagnosed with COPD and followed for several years in the out-patient clinic by pulmonologists were included. Furthermore, patients should be able to read and understand the information written in Danish. Key exclusion criteria included a known history of asthma.

At study entry, the following data were collected: smoking status including smoking history (pack-years), history of exacerbations during a 12-month period prior to inclusion and number of comorbidities.

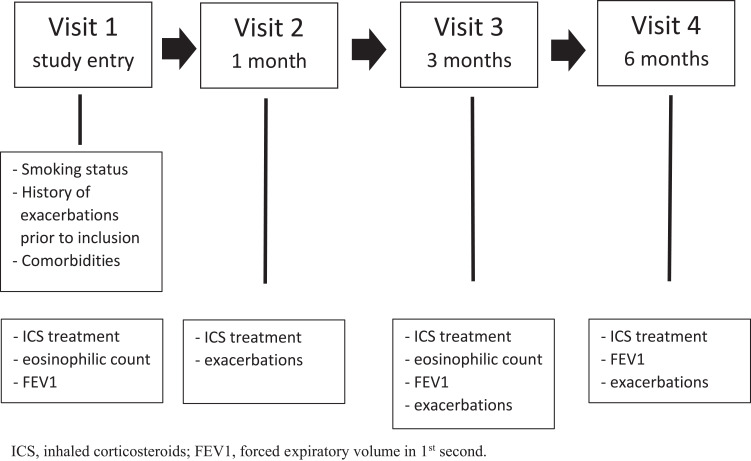

Patients were examined by a doctor at study entry and at 6 months follow-up. One month after study entry the patients were telephoned by a nurse and at 3 months follow-up patients were seen by a nurse. If needed, the patients could at any time ask to see a doctor or a nurse. At study entry and at 3 months follow-up, patients’ eosinophilic count was measured, whereas FEV1 was measured at study entry, at 3 months follow-up and at end of the study. At 1, 3 and 6 months, self-reported use of antibiotics and/or prednisolone were measured as exacerbations. At the same timepoints patients were asked whether they had resumed ICS (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study design.

Abbreviations: ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1st second.

Patients were allowed to resume ICS if needed and should not necessarily consult a doctor à priori.

The study population consisted of patients with COPD who consecutively gave informed consent for follow-up monitoring until May 2018.

COPD and COPD Exacerbations

The diagnosis of COPD was confirmed by a doctor and a pre-bronchodilator test with the forced expiratory volume in 1 sec (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) < 0.7.

COPD exacerbations were defined as an acute episode of worsening of COPD symptoms requiring a course of systemic corticosteroids and/or antibiotics reported by the patients.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint in this study was to demonstrate whether patients could manage to stay off ICS after abrupt withdrawal measured by changes in FEV1 and number of exacerbations during a 6-months follow-up period from abrupt withdrawal.

Key secondary endpoint was to see if it could be possible from the data to foresee which patients could not do without ICS treatment.

Statistical Analysis

Mean lung function and mean blood eosinophilic count at baseline and during follow-up was calculated using data from each individual included in the study. Potential differences in lung function, number of exacerbations and eosinophilic count were calculated using the Data Analysis program from the Microsoft Office Excel version 2020. For all analyses, a p-value < 0.05 was defined to be significant.

Results

Characteristics of the Study Population

Overall, 96 patients (56 females, 58.3%), mean age 70 years (51–94 years) with COPD were included in the study. During the study period, 11 patients were excluded (7 patients died, 4 patients withdrew their consent during the study period), leaving 85 patients for complete analysis.

Lung function at baseline was 0.97 L (40.55% predicted) with the majority of patients (65%) classified to be GOLD D. Most patients reported MRC 2–4. There were no never smokers, 77.1% were former smokers while 22.9% were current smokers. Mean overall packyears were 45.6.

In total, 45 patients (52,9%) had had one or more exacerbations in the past 12 months prior to inclusion. Overall blood eosinophilic count at baseline was 0.22 x 10E9/L. Patients with a history of exacerbations prior to inclusion had a non-significant higher concentration at baseline compared to patients with no history of exacerbations (0.24x10E9/L vs 0.19x10E9/L, p 0.29). Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Total Population | Completing the Study (n = 85) |

|---|---|

| Gender (%M) | 36 (42.3) |

| BMI, mean (range) | 25 (12–44) |

| Age – years, mean (range) | 70.1 (51–94) |

| GOLD (%) | |

| A | 5 (5%) |

| B | 20 (21%) |

| C | 9 (9%) |

| D | 62 (65%) |

| MRC (%) | |

| 1 | 1 (1.2%) |

| 2 | 19 (22.4%) |

| 3 | 33 (38.8%) |

| 4 | 25 (29.4%) |

| 5 | 11 (7.7%) |

| Smoking history | |

| Former smokers no. (%) | 74 (77.1) |

| Current smokers no. (%) | 22 (22.9) |

| Pack years, mean (±) | 45.55 (8–90) |

| Daily dose of ICS, mean (µg) | 740 |

| Lung function | |

| FEV1 | 0.97 (0.25–2.30) |

| FEV1% pred. | 40.55 (12–93) |

| No. of patients with exacerbations prior to inclusion (%) | 45 (52.9) |

| Blood eosinophil conc. | 0.22 (0–1.22) |

| Exa. prior to inclusion | 0.24 (0–1.22) |

| No exa. prior to inclusion | 0.19 (0–0.56) |

| Charlson comorbidity Index | |

| 0 (%) | 15 (15.6) |

| 1 (%) | 28 (29.2) |

| ≥2 (%) | 53 (55.2) |

Abbreviations: %M, percent males; BMI, body mass index; no., numbers; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1st second; pred., predicted; conc., concentration; exa, exacerbations.

Primary Endpoints

Characteristics of Patients Resuming ICS During Follow-Up

During the 6 months of follow-up, 51 patients (60%) had resumed treatment with ICS. Of these, 28 patients (54.9%) had resumed ICS treatment after 1 month, another 16 patients (31.4%) after 3 months and further 7 patients (13.7%) after 6 months. Their mean daily dose of ICS prior to inclusion was 748 µg.

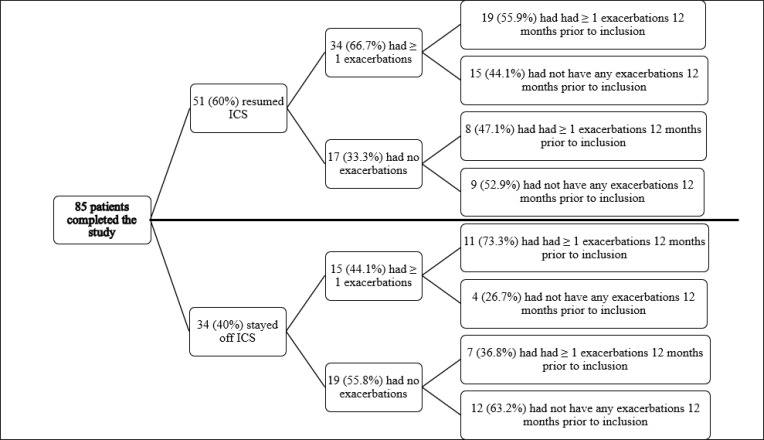

Of those resuming ICS, 34 patients (68%) experienced one or more exacerbations during follow-up, of whom 20 patients (58.8%) had been treated with antibiotics during the first month from withdrawal (Table 2). Among the 34 patients experiencing an exacerbation during follow-up, 19 patients (56%) had had one or more exacerbations prior to inclusion, whereas 8 (50%) of the 17 patients not having an exacerbation during follow-up had had one or more exacerbations prior to inclusion (Table 3 and Figure 2). In Suppl. figure 1, we have shown the proportion of patients with 2 or more exacerbations at baseline according to the two groups (+/- ICS). No difference was seen between patients resuming ICS and those who managed to stay without.

Table 2.

Exacerbations, Use of Antibiotics and FEV1 During Follow-Up

| Time from Study Entry | 1 Month | 3 Months | 6 Months | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + ICS (No. 28) | - ICS (No. 34) | + ICS (No. 44) | - ICS (No. 34) | + ICS (No. 51) | - ICS (No. 34) | |

| No of pts with exacerbations | 23 | 6 | 19 | 7 | 22 | 9 |

| No of pts treated with antibiotics | 20 | 6 | 11 | 3 | 16 | 8 |

| FEV1 L (%), mean | 0.96 (41) | 1.00 (41) | 0.97 (41) | 0.97 (40) | 0.91 (39) | 0.96 (39) |

Abbreviations: FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1st second; + ICS, resumed inhaled corticosteroids; - ICS, withdrawal from inhaled corticosteroids; no, numbers; pts, patients.

Table 3.

Baseline Characteristics Among the 2 Groups

| Total Population | Concluding the Study (n = 85) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Groups | No ICS (n = 34) | Resumed ICS (n = 51) | p-value |

| Gender (%M) | 16 (47.1) | 20 (40.0) | 0.53 |

| BMI, mean (range) | 25.7 (17–38) | 24.7 (12–44) | |

| Age – years, mean (±) | 69.9 (51–86 yrs) | 70.5 (52–94 yrs) | 0.64 |

| GOLD (%) | |||

| A | 2 (5.9) | 2 (3.9) | |

| B | 10 (29.4) | 9 (17.6) | |

| C | 2 (5.9) | 6 (11.8) | |

| D | 20 (58.8) | 34 (66.7) | |

| MRC (%) | |||

| 1 | 1 (2.9%) | 1 (2%) | |

| 2 | 10 (29.4%) | 8 (15.7%) | |

| 3 | 12 (35.3%) | 19 (37.3%) | |

| 4 | 7 (20.6%) | 16 (31.4%) | |

| 5 | 4 (11.8%) | 7 (13.7%) | |

| Smoking history | |||

| Former smokers (%) | 24 (70.6) | 42 (82.4) | 0.14 |

| Current smokers (%) | 10 (29.4) | 9 (17.6) | 0.22 |

| Pack years, mean | 45.24 | 44.74 | |

| Daily dose of ICS, mean (µg) | 708.8 | 748.0 | 0.44 |

| Lung function | |||

| FEV1 liters | 1.00 | 0.96 | 0.63 |

| FEV1% predicted | 41.0 | 40.5 | |

| Blood eosinophil conc. | 0.17 | 0.25 | 0.07 |

| No. of patients with exacerbations prior to inclusion (%) | 18 (53) | 27 (54) | 0.93 |

| Charlson comorbidity Index | |||

| 0 (%) | 5 (14.7) | 9 (17.6) | 0.72 |

| 1 (%) | 9 (26.5) | 16 (31.4) | 0.63 |

| ≥2 (%) | 20 (58.8) | 26 (51.0) | 0.48 |

Abbreviations: ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; %M, percent males; BMI, body mass index; n, numbers; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1st second; conc., concentration; no., numbers.

Figure 2.

Exacerbations according to treatment. Numbers in parentheses indicate percentages.

Abbreviation: ICS, inhaled corticosteroids.

A decline in FEV1 was seen between baseline and after 6 months (ΔFEV1 0.07 L), however, the decline was not statistically significant (p = 0.09) (Table 4). The biggest decline in FEV1 from baseline to 6 months post inclusion was seen for those who resumed ICS after 3 months (ΔFEV1 = 0.11 litres) whereas no change in FEV1 was seen for those who resumed ICS between 4 and 6 months after withdrawal (ΔFEV1 = −0.01 litres) (Suppl. Table 1).

Table 4.

Exacerbations and Lung Function During Follow-Up According to Treatment

| Patients without ICS During Follow-Up (n = 34) | Patients Resuming ICS During Follow-Up (n = 51) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients with exacerbations (%) | 15 (44.1%) | 34 (68%) | 0.09 |

| ΔFEV1 | 0.04 L | −0.07 L | 0.55 |

Abbreviations: ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; n, numbers; no., numbers; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1st second.

No statistically significant difference in eosinophilic count at baseline was seen between patients with and without exacerbations during follow-up (0.24 x10E9/L vs 0.28 x10E9/L, p > 0.5) (Table 5).

Table 5.

EOS According to Phenotype and Use of ICS

| Resumed ICS (n = 51) | |||

| Exacerbations (n = 34) | No Exacerbations (n = 17) | p-value | |

| EOS at baseline | 0.24 | 0.28 | 0.61 |

| EOS at 3 months | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0.49 |

| ICS Withdrawal (n = 34) | |||

| Exacerbations (n = 15) | No Exacerbations (n = 19) | ||

| EOS at baseline | 0.15 | 0.18 | 0.44 |

| EOS at 3 months | 0.17 | 0.24 | 0.23 |

| EOS in Exacerbators (n = 49) | |||

| Resumed ICS (n = 34) | ICS Withdrawal (n = 15) | ||

| EOS at baseline | 0.24 | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| EOS at 3 months | 0.25 | 0.17 | 0.14 |

| EOS No Exacerbations (n = 36) | |||

| Resumed ICS (n = 17) | ICS Withdrawal (n = 19) | ||

| EOS at baseline | 0.28 | 0.18 | 0.21 |

| EOS at 3 months | 0.21 | 0.24 | 0.66 |

Abbreviations: EOS, blood eosinophil count; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; n, numbers.

Characteristics of Patients Not Resuming ICS During Follow-Up

Thirty-four patients (40%) remained without ICS during follow-up. Of these, 15 patients (44.1%) experienced an exacerbation during follow-up and of these, 6 patients (40%) received antibiotics during the first month from withdrawal (Table 2). Mean daily dose of ICS prior to inclusion was 708.8 µg.

Eleven (73.3%) of the 15 patients experiencing one or more exacerbations during follow-up had had exacerbations prior to inclusion, whereas only 7 (36.8%) of the 19 patients not having exacerbations during follow-up had had exacerbations prior to inclusion (Table 3 and Figure 2).

No statistically significant difference was seen between FEV1 at baseline and after 6 months (ΔFEV1 0.04 L, p = 0.28) as well as no statistically significant difference in eosinophilic count at baseline was seen between patients with and without exacerbations during follow-up (0.15 x10E9/L vs 0.18 x10E9/L, p > 0.5) (Tables 4 and 5).

When comparing the patients resuming ICS during follow-up to patients not resuming ICS we found no statistically significant differences in age (70.5 vs 69.6 years) or sex distribution (40% vs 47.1% males, p > 0.5), nor between BMI, GOLD classification or reported MRC. FEV1 at baseline (0.96 L vs 1.00 L, p = 0.63) and eosinophilic count (0.25 x10E9/L vs 0.17 x10E9/L, p = 0.07) were not statistically different either between the two groups.

Baseline characteristics according to ICS during follow-up are shown in Table 3.

Subgroup Analyses

As FEV1 is known to be associated with sex, we performed separate subgroup analyses for men and women.

Among the 51 patients who resumed ICS during the 6 months follow-up, 20 patients (39.2%) were men. They experienced a statistically significant decline in FEV1 of 0.153 liters, p < 0.05, as well as a non-significant decline in blood eosinophils (Δ0.08 x10E9/L). On the opposite, the 31 women (60.8%) did not experience any change in FEV1 from baseline to 6 months follow-up (ΔFEV1 −0.011 liters, p = 0.72), whereas we measured a non-significant increase in blood eosinophils from baseline to 3 months follow-up (Δblood eosinophils 0.03, p = 0.53).

Among the remaining 34 patients without ICS after 6 months from withdrawal, 16 patients (47.1%) were men. They experienced a small non-significant decrease in FEV1 of 0.086 liters (p = 0.27) but no difference in blood eosinophils from baseline to 3 months of follow-up (Δblood eosinophils 0.005, p = 0.82). The 18 women (52.9%) had no change in FEV1 from baseline to 6 months of follow-up (ΔFEV1 0.0039, p=0.92), however, we found a statistically significant increase in blood eosinophils from 0.15 x10E9/L to 0.23 x10E9/L, p<0.05.

Furthermore, we performed subgroup analyses for the seven patients who died during follow-up. Overall, compared to patients alive at end of follow-up, these patients had more severe COPD with six patients classified as having COPD GOLD D with a mean lung function at 0.68 liters (range 0.25–1.19 liters). In line with this, five patients had had exacerbations prior to inclusion. However, only one patient had resumed treatment with ICS after one month and another patient after 3 months (Suppl. Table 2).

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate whether patients with COPD receiving triple therapy with a LAMA, a LABA and ICS could manage to stay off ICS after abrupt withdrawal. Eighty-five patients were included of whom 51 (60%) resumed treatment with ICS during follow-up. No differences regarding age, gender, smoking status, lung function or number of exacerbations prior to inclusion were found between patients resuming treatment with ICS and those not resuming treatment.

During follow-up, no significant change in lung function was seen between the two groups; however, a tendency of worsening of lung function was seen for patients resuming ICS (ΔFEV1 −0.07 L) whereas patients without ICS experienced a slight increase in lung function (ΔFEV1 0.04 L). Thirty-four patients (68%) resuming ICS experienced an exacerbation compared to 15 patients (44%) not resuming ICS (p = 0.039). This difference in exacerbations could be misinterpreted as a consequence of treatment with ICS, however, ICS treatment was most likely resumed following an exacerbation. Another, more likely, explanation for this finding could be that patients who did not manage to stay off ICS were more susceptible to variations in symptoms and felt more comfortable when treated with ICS and consequently had a lower threshold for exacerbations.

No differences from baseline in lung function, eosinophilic count or number of exacerbations prior to inclusion were reported between the two groups and could therefore not explain why some patients managed to stay off ICS during follow-up.

In recent years, it has become evident that not all patients with COPD will benefit from ICS therapy, particularly if they are maintained on effective dual bronchodilation with a LABA and LAMA.14 It is necessary to identify on a case-by-case basis who will benefit from ICS therapy, and if a patient is already treated with ICS whether it will be beneficial to step down or even stop ICS treatment without doing harm. Several previous studies have shown that abrupt withdrawal of ICS was associated with an increased risk of exacerbations and worsening of lung function12,16,20 resulting in studies proposing stepwise ICS withdrawal.21–23 Despite of this, we have chosen abrupt withdrawal of ICS to make the study doable, as more patients were expected to drop out during a prolonged stepwise discontinuation. Furthermore, abrupt withdrawal is more feasible in a real-life clinical setting making this study applicable to most outpatient clinics. In our study, we did not find an overall increased risk of exacerbations or worsening of lung function after abrupt withdrawal of ICS. This is in line with a previous study (SUNSET) from 2018 evaluating the efficacy and safety of direct de-escalation from long-term triple therapy in non-frequently exacerbating patients with COPD.24 However, only 34 of 85 patients in our study managed to stay off ICS during follow-up. In the SUNSET study, it was shown that patients with ≥300 blood eosinophils/µL had a higher risk of exacerbation after ICS withdrawal indicating that these patients benefit from ICS in combination with LAMA/LABA.24 In our study, we were not able to show this regarding risk of exacerbations. However, we did find a tendency towards higher blood eosinophils in the group of patients who resumed ICS during follow-up.

One of the major strengths of this study is that data is collected in real-time which reflects patients’ ability to withdraw ICS as they could at any time resume treatment with ICS. To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the ability to accept abrupt withdrawal of ICS in patients treated with ICS for a long time. Another strength is that measurement of lung function was performed by the same staff at every visit and in the same setting resulting in an overall high quality of spirometries.

The study has some limitations as well. The most important one might be that patients were not asked why they needed to resume treatment with ICS. Information of possible worsening of dyspnea, sputum production, quality of life and anxiety would have been useful as predictors of resuming ICS. With this information, it could have been possible in future settings to inform patients about situations and adverse effects which could give rise to a need for resuming ICS and thereby prepare the patients better for this. In line with this, we do not have data on the initial indications for treatment with ICS. However, a study from 2010 conducted in Denmark showed that 75% of patients diagnosed with COPD were started on ICS by their General Practitioner indicating that this was the treatment of choice some years ago.15 Another limitation is that only patients with a known history of asthma are excluded. We have not performed spirometry with reversibility prior to inclusion as this would have required patients to pause their inhalation treatment for up to 4 weeks prior to spirometry which we did not find ethically correct. Patients resuming ICS could therefore theoretically have a co-diagnosis of asthma explaining their need for ICS in everyday life without our knowledge. However, we find this very unlikely as patients were all known with a diagnosis of COPD, had a mean age of 70 years and were all former or current smokers. Finally, with 91 patients included, the study might have been underpowered. With a greater sample size, some of the observed differences in eosinophilic count at baseline and number of exacerbations during follow-up might have been statistically significant.

In conclusion, abrupt withdrawal of ICS was possible in some patients. However, more than half of the patients resumed ICS during follow-up. No differences in lung function were seen between the two groups during follow-up as well as no differences from baseline in lung function, eosinophilic count or number of exacerbations prior to inclusion were reported between the two groups. However, significantly more patients who resumed treatment with ICS experienced one or more exacerbations during follow-up.

Based on results from this study we were not able to foresee who will be able to manage without ICS and who will resume treatment with ICS.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the patients who participated in the study. They also want to thank Mette Schmidt Moeller from Department of Medicine, Hospital Little Belt Vejle, for helping recruiting patients and journal audit. This research was supported by Udviklingsrådet, Development Region, Hospital Lillebaelt, Denmark; and Department of Medicine, Hospital Little Belt Vejle and Kolding, Denmark. The abstract of this paper was presented as an E-poster at the European Respiratory Society International Congress 2020. The poster’s abstract was published in “Poster Abstracts” in European Respiratory Journal 2020; 56: Suppl. 64, 2420, DOI: 10.1183/13993003.congress-2020.2420.

Ethical Considerations

Informed consent was obtained. Confidentiality was promised, and participants were told that they could withdraw from the study at any time, with no impact on their treatment and care. The Regional Ethics Committee was informed but determined that the study required no formal ethical approval as the Committee found that the project was a quality assurance study that was not subject to notification to The Regional Ethics Committee. The study was approved by the Regional Danish Data Protection Agency; ID number: 2008-58-0035.

Disclosure

Dr Anne Orholm Nielsen reports personal fees from Chiesi, grants from Boehringer-Ingelheim, outside the submitted work. Dr Steffen Helmer Kristensen reports personal fees from AstraZeneca A/S, Novartis Healthcare A/S, and GlaxoSmithKline Pharma A/S, outside the submitted work. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; 2020. Available from: www.goldcopd.org. Accessed April28, 2020.

- 2.Barnes PJ. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin Chest Med. 2014;35(1):71–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2013.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vestbo J. COPD: definition and phenotypes. Clin Chest Med. 2014;35(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2013.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miravitlles M, Calle M, Soler-Cataluña JJ. Clinical phenotypes of COPD: identification, definition and implications for guidelines. Arch Bronconeumol. 2012;48(3):86–98. doi: 10.1016/j.arbr.2012.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee JH, Lee YK, Kim EK, et al. Responses to inhaled long-acting beta-agonist and corticosteroid according to COPD subtype. Respir Med. 2010;104(4):542–549. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Avdeev S, Aisanov Z, Arkhipov V, et al. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids in COPD patients: rationale and algorithms. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2019;14:1267–1280. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S207775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ernst P, Saad N, Suissa S. Inhaled corticosteroids in COPD: the clinical evidence. Eur Respir J. 2015;45(2):525–537. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00128914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loke YK, Cavallazzi R, Singh S. Risk of fractures with inhaled corticosteroids in COPD: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials and observational studies. Thorax. 2011;66(8):699–708. doi: 10.1136/thx.2011.160028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suissa S, Kezouh A, Ernst P. Inhaled corticosteroids and the risks of diabetes onset and progression. Am J Med. 2010;123(11):1001–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agusti A, Fabbri LM, Singh D, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids in COPD: friend or foe? Eur Respir J. 2018;52(6):1801219. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01219-2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yawn BP, Li Y, Tian H, Zhang J, Arcona S, Kahler KH. Inhaled corticosteroid use in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and the risk of pneumonia: a retrospective claims data analysis. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2013;8:295–304. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S42366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaplan AG. Applying the wisdom of stepping down inhaled corticosteroids in patients with COPD: a proposed algorithm for clinical practice. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10(1):2535–2548. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S93321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janson C, Lisspers K, Ställberg B, et al. Osteoporosis and fracture risk associated with ICS use among Swedish COPD patients: the ARCTIC study. Eur Respir J. 2020:2000515. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00515-2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wedzicha JA, Banerji D, Chapman KR, et al. Indacaterol-glycopyrronium versus salmeterol-fluticasone for COPD. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2222–2256. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1516385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ulrik CS, Hansen EF, Jensen MS, et al. Management of COPD in general practice in denmark-participating in an educational program substantially improves adherence to guidelines on behalf of the KVASIMODO II Study Group. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2010;5:73. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S9102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wouters EFM, Postma DS, Fokkensà B, et al. Withdrawal of fluticasone propionate from combined salmeterol/fluticasone treatment in patients with COPD causes immediate and sustained disease deterioration: a randomised controlled trial for the COSMIC (COPD and Seretide: a Multi-Center Intervention and Characterization) Study Group. Thorax. 2005;60:480–487. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.034280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rossi A, Van Der Molen T, Del Olmo R, et al. INSTEAD: a randomised switch trial of indacaterol versus salmeterol/fluticasone in moderate COPD. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(6):1548–1556. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00126814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rossi A, Guerriero M, Corrado A, et al. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids can be safe in COPD patients at low risk of exacerbation: a real-life study on the appropriateness of treatment in moderate COPD patients (OPTIMO). Respir Res. 2014;15(1). doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-15-77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vogelmeier C, Worth H, Buhl R, et al. Real-life inhaled corticosteroid withdrawal in COPD: a subgroup analysis of DACCORD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:487–494. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S125616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Der Valk P, Monninkhof E, Van Der Palen J, Zielhuis G, Van Herwaarden C. Effect of discontinuation of inhaled corticosteroids in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the cope Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(10):1358–1363. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200206-512OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Magnussen H, Disse B, Rodriguez-Roisin R, et al. Withdrawal of inhaled glucocorticoids and exacerbations of COPD. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(14):1285–1294. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1407154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chalmers J, Bobak A, Scullion J, Murphy A. Withdrawal of ICS treatment in primary care: a practical guide. Pract Nurs. 2017;28(1):22–27. doi: 10.12968/pnur.2017.28.1.22 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chalmers JD. POINT: should an attempt be made to withdraw inhaled corticosteroids in all patients with stable GOLD 3 (30% ≤ FEV1 < 50% predicted) COPD? Yes. Chest. 2018;153(4):778–782. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.01.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chapman KR, Hurst JR, Frent S-M, et al. Long-term triple therapy de-escalation to indacaterol/glycopyrronium in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (SUNSET): a randomized, double-blind, triple-dummy clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198(3):329–339. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201803-0405OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]