Abstract

Income inequality among U.S. families with children has increased over recent decades, coinciding with a period of significant reforms in federal welfare policy. In the most recent reform eras, welfare benefits were significantly restructured and redistributed, which may have important implications for income inequality. Using data from the 1968–2016 March Supplement to the Current Population Survey (N = 1,192,244 families with children) merged with data from the historical Supplemental Poverty Measure, this study investigated how income inequality and, relatedly, the redistributive effects of welfare income and in-kind benefits changed, and whether such changes varied across states with different approaches to welfare policy. Results suggest that cash income from welfare became less effective at reducing income inequality after the 1996 welfare reform, because the share of income coming from cash welfare fell and was also less concentrated among the neediest families. At the same time, tax and in-kind benefits reduced inequality until the Great Recession. Consistent with the “race to the bottom” hypothesis, results suggest that the redistributive effects of welfare income dropped in all states regardless of their approach to welfare policy.

1. Introduction

Inequality in U.S. family income has significantly increased since the late 1960s (see, e.g., McCall and Percheski 2010; Pikkety and Saez 2006; Pikkety 2014).1 The richest Americans have experienced the fastest income growth, while income among the bottom 50% has stagnated (Piketty, Saez, and Zucman 2018). Income inequality rose twice as fast among families with children as it did among all workers (McCall and Percheski 2010; Western, Bloome and Percheski 2008). This is concerning given that income inequality is associated with slowed intergenerational mobility (Beller and Hout 2006), widening achievement gaps (Jencks, Owens, Shollenberger, and Zhu 2010; Reardon 2012), and disparities in health and well-being (Oishi, Kesebir, and Diener 2011).

This dramatic rise in income inequality has been attributed to three primary causes: (a) the growth of top incomes, (b) changes in family formation and family structure, and (c) changes in social policy and economic redistribution by the state (McCall and Percheski 2010). Inequality due to changes in family structure (Martin 2006) and rising top incomes, particularly investment income, (Piketty, Saez, and Zucman 2018; Pikkety and Saez 2006; Pikkety 2014; Lemieux 2008) have received a great deal of scholarly and media attention. Although there is existing literature about the role of social policy for reducing poverty (Burkhauser and Sabia 2007; Gunderson and Ziliak 2004; Kenworthy 1999; Neumark et al 2005), we know less about how it has affected the distribution of income (for a notable exception see Joo 2011). Needs-based income transfer programs can play an important role in reducing income inequality (Joumard, Pisu, and Bloch 2012).

The United States welfare state has significantly evolved over time, and these changes may have important implications for family income inequality. Although federal spending on the welfare system has generally increased over time, it has shifted away from programs that provide cash assistance and increasingly prioritized in-kind and tax benefits (Moffitt 2015). As a result, support has generally increased for the elderly, disabled, and working poor with higher incomes, and decreased for single mothers with children and the poorest families (Moffitt, 2015), which may exacerbate inequality. In addition, states have more responsibility and freedom to implement these policies, resulting in significant geographic variation in the generosity of benefits. This variation may also compound inequality in states with the most restrictive practices.

We build on existing research by focusing on the role of different social policy eras on family income inequality in the United States, over time and across states. Specifically, we decompose family income inequality, measured by the Gini coefficient, to evaluate how specific shifts in earnings, welfare, tax and in-kind benefits, and investment income contributed to income inequality in five distinct policy eras. We also examine how changes in the share of total family income from welfare benefits and the distribution of welfare benefits among families contributed to income inequality across state clusters defined by approach to welfare policy. More specifically, we test competing hypotheses about devolution leading to a race to the bottom or to continued state-level differences in the redistributive effects of state welfare programs.

2. Welfare Eras in the United States

The United States has witnessed several eras of welfare reform. The welfare state was initially launched during the Great Depression with the passage of the Social Security Act of 1935. This Act created three programs—Social Security, Unemployment Insurance, and Aid to Dependent Children (later renamed Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC)), which provided cash assistance. These programs remained relatively stable until 1964, when President Johnson announced the War on Poverty. This marked the beginning of a significant expansion of the welfare state through the 1970s. Indeed, many of the social welfare programs that exist today were created or expanded during this period, including the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly called Food Stamps) (1965), Medicare and Medicaid (1965), Supplemental Security Income (1974), the Women’s, Infants, and Children (WIC) program (1972), and the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) (1975). During this era there was an expectation of standardized welfare eligibility criteria and an emphasis on the equity of benefits offered across families (Mettler 2000).

In the 1980s, however, a new era of reform was ushered in as welfare became increasingly stigmatized. Reductions to welfare benefits were initiated by the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1981. Under this law, federal oversight of welfare was reduced, the benefits were reduced, and states began experimenting with work programs, foreshadowing the major reform to welfare in the mid-1990s. This emphasis on work for welfare recipients was further strengthened through the Federal Family Support Act of 1988, which facilitated stricter sanctions for recipients who were not working, and incentivized job training and time limits for cash assistance (Moffitt 2008; Zylan and Soule 2000).

The next major reform occurred in 1996 with the passage of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA),, which replaced the Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) program with Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF). Whereas AFDC was an entitlement program that guaranteed benefits to those who qualified with no time limits, TANF implemented federal lifetime limits on welfare receipt, stricter work requirements, and more severe sanctions for recipients, including benefit reduction and case closure for noncompliance (Danziger 2010; Gais and Weaver 2002). Under TANF, the welfare caseload dropped significantly (Shaefer, Edin, & Talbert, 2015).

Aggregate spending on the social safety net continued to rise even as welfare spending decreased due to expansions in other programs, such as Social Security Insurance (SSI), the EITC, the Child Tax Credit (CTC), and SNAP (Moffitt, 2015). . Indeed, supplemental poverty measures that account for tax credits and in-kind benefits suggest that these programs—especially tax credits and food and nutrition programs— played a large role in reducing poverty over time (Fox, Wimer, Garfinkel, Kaushal, & Waldfogel, 2015; Wimer, Fox, Garfinkel, Kaushal, and Waldfogel 2016). These types of resources are not typically included in measures of income inequality because they are not as fungible as cash, but they nevertheless contribute to the economic security of families.

Welfare reforms have limited the availability of cash assistance and unequally redistributed non-cash benefits. Benefits have shifted away from some of the poorest families, such as those with no earnings, to working poor families with higher incomes (Moffitt, 2015; Joo 2011). Since welfare reform, families with income below 50% of the official poverty threshold have received less assistance from public programs, while families with incomes between 50-150% of the poverty line have received more assistance (Ben-Shalom, Moffitt, Scholz, & Jefferson, 2012; Hoynes and Patel, 2018). The scarcity of cash assistance from welfare puts considerable burden on the most impoverished families, and potentially contributes to growing income inequality among families with children.

3. State Variation in Welfare Benefits

There were also significant changes to the funding structure of welfare after 1996. Whereas AFDC was an entitlement program with matching federal grants, TANF was funded through federal block grants that gave states additional flexibility to design and implement their own programs. States became responsible for paying all of the costs of welfare benefits beyond the block grant amount (Brueckner 2000). Access to benefits therefore became more restricted and dependent on state discretion. This could potentially exacerbate income inequality among families with children living in different states.

With this devolution of responsibility for welfare policy implementation, welfare policies became increasingly heterogeneous across states (Meyers, Gornick and Peck 2002; Gais and Weaver 2002). For example, there is considerable variation in benefit eligibility and sanctions for non-compliance. Some states have adopted shorter time limits, stricter work requirements, and family caps which deny additional benefits to children conceived by welfare recipients. Others have removed the welfare time limits, liberalized earnings and asset disregards, and adopted more lenient sanctions for non-compliance (Soss et al 2011; Gais and Weaver 2002). Some scholars argued that increased state control of welfare benefits (even before the passage of PRWORA) would lead to a “race to the bottom” (Peterson and Rom 1990), whereby states would offer less generous benefits than they might have otherwise to deter the migration of poor families seeking the most generous welfare benefits. Although there is limited evidence of welfare migration (Gais and Weaver 2002; Berry et al 2003; Meyers, Gornick and Peck 2002), policymakers do consider benefits available in neighboring states in setting benefit levels (Brueckner 2000). Others argue instead that considerable heterogeneity among state benefit levels has emerged (Gais and Weaver 2002) or that states have exhibited path dependency in continuing on their prior trajectory of welfare benefit generosity (Aratani, Lu, and Aber 2014).

States can be grouped according to their welfare policy approaches. Meyers, Gornick and Peck (2001; 2002) analyzed the adequacy, inclusion, and commitment of states to eleven policies directly impacting the economic resources available to children and identified five state clusters: (1) the minimal states provided the most minimal support for families with children in all dimensions, (2) limited states provided slightly more income support than the minimal states but were at or below the national average for inclusion and adequacy, (3) conservative states provided low levels of income support and relied on policies that enforce private responsibility (e.g. child support enforcement and mandatory work requirements), (4) generous states scored higher than the national average on the adequacy and inclusiveness of cash assistance but near the national average on tax policy, child support and the JOBS program, and (5) the integrated states scored at or well-above the national average on all dimensions. These groupings remain salient, given evidence that states have been relatively consistent in their approaches over time (Meyers et al. 2001, Aratani, Lu, and Aber 2014).

4. Hypotheses

The evolution of the social safety net has important implications for income inequality. Our first research objective is to examine how income inequality among families with children changed across different welfare eras. Our hypothesis (H1) is that family income inequality grew more rapidly in the PRWORA era, as cash assistance was limited, as compared to the welfare expansion era.

Our second research objective is to examine how shifts in the sources of family income, and more specifically the shrinking welfare safety net for the poorest Americans (Moffitt 2015), have contributed to the growth in family income inequality. Maintaining our focus on changes in welfare benefits over time, we predict that the decline in the proportion of cash welfare and its weakening negative association with family income (Moffitt 2015) have contributed to overall increases in family income inequality (H2).

Finally, our third research objective is to examine variation in these sources of income inequality across different state policy regimes. Given the mixed evidence for a “race to the bottom” among states, we have developed competing hypotheses for this research objective. Persisting differences among state clusters over time such that families in minimal, limited, and conservative states have more unequal income distributions than families in generous or integrated states (H3A) would be evidence in support of a path dependence model. Alternatively, a convergence over time among state clusters in total income inequality would support the “race to the bottom” hypothesis (H3B).

5. Methods

5.1. Data

This study used data from the 1968-2016 March Supplements to the Current Population Survey (CPS), drawn from IPUMS-CPS (King et al. 2010). The CPS sample is representative of the non-institutional population in the United States. The sample for this analysis included 1,192,244 families with children, with between 23,000 and 100,000 interviewed each year.

5.2. Measures

5.2.1. Total family income.

The March Supplement to the CPS collected self-reported information about total family income and its sources: earnings from wages and salary, investments, businesses, and farming, as well as income received from welfare, disability, worker’s compensation, and unemployment benefits, social security, retirement and pensions, and alimony2. The Census Bureau top-coded income values for individuals and families with very high or low incomes in the CPS to prevent identification of sample members3. Following Gottschalk and Moffitt (2009), we excluded families with total family incomes in the top 1% and bottom 1% of family incomes. Consequently, the results presented in this study represent income inequality for families in the inner 98% of the total family income distribution only.

To capture the full range of resources available to families, we also included measures of the family’s tax and in-kind benefits using data from the historical Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM), compiled by the Center on Poverty and Social Policy at Columbia University (Wimer, Fox, Garfinkel, Kaushal, Laird, Nam, Nolan, Pac, and Waldfogel 2017). This measure included the value of benefits from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), National School Lunch Program (NSLP), Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP), Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC), 2008 Economic Stimulus payments, the Federal Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), and housing subsidies. For years in which the information was not directly measured with self-reported data in the CPS, resources were estimated using imputation procedures based on administrative data (for a detailed description of the imputation procedures see the appendix in Fox et al. 2015).

Our measure of total family income included income from all family members and five income sources: (1) earned income (from wages and salary, business income, and farming income), (2) investment income (from dividends, interests, and rent), (3) cash welfare income (from public assistance programs such as Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), as well as income from Supplemental Security Income), (4) tax and in-kind benefits (from SNAP, NSLP, LIHEAP, WIC, as well as housing subsidies, 2008 Economic Stimulus payments, and EITC), and (5) income from all other sources (from pensions and retirement accounts, child support, alimony, survivor benefits, unemployment insurance, worker’s compensation, and all other sources of income). A key objective of this research is to examine how, following the passage of the PRWORA, the shift from cash welfare to in-kind benefits and tax benefits impacted family income inequality. For this reason, we combine tax and in-kind benefits into one income source, which we compare with income from cash welfare in this analysis.

5.2.2. Family income inequality.

Family income inequality was measured using the Gini coefficient, a widely-used measure of income inequality that describes the extent to which the distribution of family income differs from a perfectly equal distribution (i.e., all families have the same income) (Luebker 2010). The Gini coefficient ranges from 0, indicating perfect equality, to 1, indicating perfect inequality. In this study, Gini coefficients were computed for total family income in each survey year from 1968 to 2016 for families with any children between the ages of birth and 17 years.

5.2.3. Family structure.

We account for population-level changes in family structure over time. During much of the study period, eligibility for welfare benefits was tied to family structure as a result of restrictive eligibility criterion for families with an able-bodied adult male in the household. Changes in family structure also directly influence levels of income inequality because of income differences across family types. Indeed, changes in family structure, such as the proliferation of nonmarital childbearing, cohabitation, and divorce, account for 41% of the increase in inequality between 1976 and 2000 (Martin 2006).

To code family structure, we first used the marital status of the household head, which was collapsed into categories for (a) married, (b) divorced/separated, (c) never married, and (d) widowed. The CPS did not directly collect information about cohabitation until 1990, so we indirectly inferred this relationship by adapting the “Adjusted POSSLQ” procedure outlined by Casper and Cohen (2000). A family is defined as cohabiting if it meets the following criteria: (a) there is an unmarried householder who is not living in group quarters, (b) there is another unmarried adult who is the opposite sex of the household, is not related to the householder, and is age 18 or older, and (c) there are no other unrelated adults in the household.4

5.2.4. Demographic characteristics.

Over the analysis period, there was significant growth in the proportion of non-White families (which has been shown to be positively associated with income inequality), but also an increase in the educational attainment in the population (which has been shown to be negatively associated with income inequality) (Moller, Alderson, Nielsen 2009). We measured racial composition with an indicator for White vs. non-White. Educational attainment is measured by the highest degree attained in the family.

5.2.5. Welfare eras.

We define five welfare eras: (1) welfare expansion in 1968-1980, (2) beginning phase of welfare reform in 1981-1987, (3) increased work requirements in 1988-1995 (4) the period following passage of PRWORA, 1996-2007, and (5) the period following the Great Recession in 2008-2016.

5.2.6. State policy clusters.

We define state policy clusters based on the five state policy regimes identified by Meyers, Gornick, and Peck (2001), as described in the background section. The minimal states include Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and West Virginia. Limited states include Arizona, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Missouri, North Carolina, New Mexico, Nevada, Oklahoma, and Virginia. The conservative states include Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, Montana, North Dakota, Nebraska, South Dakota, Utah, and Wyoming. The generous states include California, Colorado, Connecticut, Iowa, Illinois, Massachusetts, Maine, Michigan, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Washington. The final cluster, the integrated states, include Maryland, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Ohio, Vermont, and Wisconsin.

5.3. Method

The Gini coefficient for total family income in welfare policy era y, Gy, can be represented as:

| (2) |

where Sky is the share of income from source k in welfare policy era y, Gky is the Gini coefficient for income from source k in era y, and Rky is the correlation of income from source k in era y with the distribution of total income in era y. The influence of any income source k on total family income inequality depends on: (1) how large a share of total income it represents, (2) how unequally distributed it is, and (3) how it is correlated with the distribution of total income. Income sources that represent a large share of total family income and that are more unequally distributed have larger effects on inequality. Income sources that are positively correlated with total family income (i.e., the income source is disproportionately held by those at the top of the income distribution) increase inequality and those that are negatively correlated (i.e., the income source is disproportionately held by those at the bottom of the income distribution) decrease inequality.

The effect of change in a specific source of income k on total family income inequality, holding income from other sources constant, can be estimated by taking the partial derivative of the Gini coefficient with respect to a percent change e (in this instance 1%) in source k. The percent change in inequality resulting from a 1% increase in income from source k is equal to:

To better understand the role of welfare policy changes in change in family income inequality over time, we decomposed the Gini coefficient by the five income sources. We used the descogini command in Stata (Lopez-Feldman 2006), which implements the Lerman and Yitzhaki (1985) decomposition approach for estimating the marginal effects that each income source has on inequality.

Our analysis first decomposes change over time in family income inequality by key historical welfare policy periods and then by state clusters defined by welfare policy regime.

To account for population-level changes in family structure, racial composition, and educational attainment over time, we applied post-stratification weights that reweighted the CPS sample so that the family structure distribution (married, cohabiting, separated, divorced, widowed, and never married), racial composition (White vs. non-White), and educational attainment (highest degree attained in the family) observed for the 1968 CPS sample was preserved for all subsequent years5.

We present the fully adjusted estimates in the tables; unadjusted results can be found in the appendix.

6. Results

6.1. Trends in Family Income Inequality among Families with Children

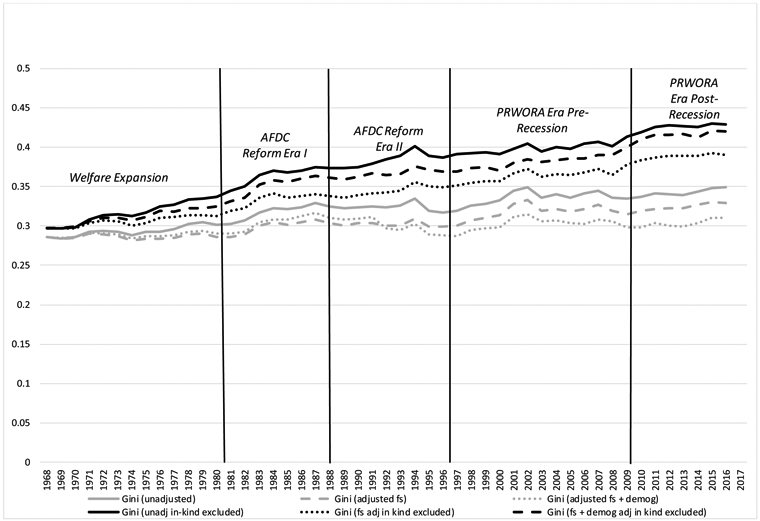

Figure 1 displays Gini coefficients for total family income from 1968 to 2016 among families with children. In this figure, the black lines display the Gini coefficients for total family income, excluding tax and in-kind benefits. The grey lines present the Gini coefficients when the tax and in-kind benefits are included in the calculation of total family income. The solid lines in this figure display estimates of the Gini coefficient when the data are weighted to be representative of the population of families with children in the designated survey year. We also present estimates that account for shifts in family structure (dashed lines), and family structure, race, and education (dotted lines). The coefficients displayed on the dotted lines can be interpreted as the Gini coefficient that would have been observed if family structure, racial composition, and educational attainment were unchanged over the 1968 to 2016 period.

Figure 1:

Gini Coefficients for Total Family Income by Survey Year, 1968-2016 March Current Population Survey

To analyze the impact of tax and in-kind welfare benefits on total inequality, we first examine the income inequality trend with these benefits excluded and then with them included in the calculation of total income. Figure 1 illustrates that income inequality among families with children has grown steadily since the early 1970s when these benefits are excluded (black lines). The Gini coefficient (excluding in-kind benefits) among families with children was 0.30 in the late 1960s (black solid line). Between 1968 and 2016, income inequality increased by 43% to a Gini coefficient of 0.43. To contextualize this result, a Gini coefficient in the low-to-mid 0.40s is comparable to the level of income inequality in contemporary Nigeria, Kenya, and Russia, while one in the upper 0.20s and low 0.30s is comparable to the level of income inequality in Finland, Germany, Belgium, and Canada (Central Intelligence Agency 2013).

Income inequality increased in part because the share of children in married families declined and the share in single parent families rose since the late 1960s. In fact, when estimates of the Gini coefficient are reweighted to preserve the distribution of family structures in the population in 1968, the change in the Gini coefficient (excluding tax and in-kind benefits) over this time period is noticeably reduced (black dotted line).

When estimates of the Gini coefficient (excluding tax and in-kind benefits) are reweighted to preserve the distribution of family structures, race, and education in 1968, the Gini coefficient increases to levels similar to the unadjusted Gini coefficients (black dashed line). Between 1968 and 2016, the Gini coefficients adjusted for family structure and demographic characteristics increased from 0.30 to 0.42, an increase of 40%. This suggests that changes in family structure were counterbalanced by changes in racial composition and educational attainment.

Although the trendline in family income inequality excluding tax and in-kind benefits is progressively upward, when these benefits are included, unadjusted increases in inequality over time are reduced by half (gray solid line). Once the Gini coefficient is adjusted for family structure and demographic characteristics (gray dotted line), the increase in income inequality over the analysis period is even smaller (only 7%).

Although the overall trend in the Gini coefficient is relatively flat once tax and in-kind benefits are included in the calculation of total income and adjustments are made for changes in family structure and the demographic composition of the population over time, the rate at which inequality changed varied over this period. During the welfare expansion era (1968-1980), the Gini coefficient (including tax and in-kind benefits and adjusted for family structure and demographic characteristics) increased by only 1.4%, rising from 0.286 to 0.290, with an annualized growth rate of 0.1%. During the initial period of AFDC reform (1980-1987), the Gini coefficient rose much more sharply, increasing by 9.2%, with an annualized growth rate of 1.5%. The rate of growth for family income inequality then declined starting in the late 1980s and leading up to the passage of the PRWORA. In the latter period of AFDC reform (1988-1995) the Gini coefficient decreased by 6.7% with an annualized growth rate of −1%, but then in the pre-recession PRWORA era (1996-2007) income inequality increased again by 6.8%, with an annualized growth rate of 0.6%. Family income inequality continued to slightly increase in the post-recession PRWORA era (2008-2016), with the Gini coefficient increasing from 0.306 to 0.310, a 1.4% increase with an annualized growth rate of 0.2%. If we further break down the period of analysis and look at changes in the Gini coefficient in the recovery period following the recession (2008-2011) versus the period of economic growth (2012-2016), we see that inequality declined slightly in the wake of the recession, at an annualized rate of −0.2% but then increased again from 2012 to 2016, at an annualized rate of 0.8%.

This provides partial support for H1; we found that the rate of growth in inequality was greater immediately following the passage of PRWORA and also following the recovery from the Great Recession than in the welfare expansion era, but it was lower in the period of recession from 2008-2011. However, it is important to note that overall, once tax and in-kind benefits are included in the calculation of the Gini and changes in family structure and demographic characteristics are accounted for, the overall trend in total family income inequality is relatively flat between 1968 and 2016. Nevertheless, although tax benefits in particular provide economic resources to families, they are not equivalent to monthly cash income because they are distributed as lump sum payments and are also less concentrated in the hands of the poorest families. In-kind benefits are also not equivalent to cash welfare because they provide families with less flexibility in managing household expenses.

6.2. Sources of Growth of Family Income Inequality among Families with Children

To better understand how major changes in welfare policy in the U.S., especially the growing emphasis on in-kind benefits instead of cash welfare, impacted income inequality, we decomposed the Gini coefficient by income source and welfare policy era. Table 1 presents results from these decompositions. The upper part of the table displays the three components that determine the Gini coefficient: (1) the share of income from each source (Sk); (2) the Gini coefficient for income from source k (Gk), and (3) the correlation of income from the source with the distribution of total family income (Rk). Sk indicates the relative importance of the kth income source, Gk describes the level of inequality for the distribution of income from source k, and Rk measures the strength and direction of the linear association between income source k and the distribution of total family income.

Table 1:

Decomposition of Gini Coefficient by Welfare Era: 1968-2016 March Current Population Survey

| Family Structure and Demographic Adjusted Estimates | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Welfare Expansion 1968- 1980 |

AFDC Reform Era I 1981- 1987 |

AFDC Reform Era II 1981- 1995 |

PWORA Era Pre- Recession 1996- 2007 |

PWORA Era Post- Recession 2008- 2016 |

|

| Components of Gini Decomposition | |||||

| Share of Income (Sk) | |||||

| Earned | 87.7% | 84.5% | 82.4% | 81.2% | 74.2% |

| Welfare | 1.2% | 1.3% | 1.3% | 0.8% | 0.6% |

| Investment | 1.6% | 2.1% | 1.8% | 1.8% | 1.4% |

| Other Income | 4.2% | 4.8% | 4.9% | 4.4% | 4.8% |

| In Kind | 5.4% | 7.4% | 9.6% | 11.7% | 19.0% |

| Gini Coefficient (Gk) | |||||

| Total Income | 0.29 | 0.31 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 |

| Earned | 0.35 | 0.39 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.44 |

| Welfare | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.96 |

| Investment | 0.97 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.99 |

| Other Income | 0.87 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.86 | 0.87 |

| In Kind | 0.80 | 0.83 | 0.80 | 0.76 | 0.69 |

| Correlation (Rk) | |||||

| Earned | 0.92 | 0.89 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.83 |

| Welfare | −0.35 | −0.26 | −0.22 | −0.19 | −0.15 |

| Investment | 0.54 | 0.53 | 0.57 | 0.62 | 0.66 |

| Other Income | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.14 |

| In Kind | 0.11 | 0.00 | −0.04 | −0.05 | 0.13 |

| Estimated Impact of Income Components on Total Inequality | |||||

| Proportionate Contribution to Total Inequality | |||||

| Earned | 97.4% | 97.3% | 97.5% | 96.8% | 89.8% |

| Welfare | −1.4% | −1.0% | −0.9% | −0.5% | −0.3% |

| Investment | 2.8% | 3.7% | 3.4% | 3.7% | 3.1% |

| Other Income | −0.3% | 0.1% | 1.0% | 1.5% | 1.9% |

| In Kind | 1.6% | −0.1% | −1.0% | −1.5% | 5.5% |

| Elasticity | |||||

| Earned | 0.097 | 0.128 | 0.151 | 0.156 | 0.157 |

| Welfare | −0.026 | −0.023 | −0.022 | −0.013 | −0.009 |

| Investment | 0.012 | 0.016 | 0.015 | 0.018 | 0.017 |

| Other Income | −0.045 | −0.046 | −0.039 | −0.029 | −0.029 |

| In Kind | −0.038 | −0.074 | −0.106 | −0.132 | −0.135 |

The bottom portion of the table describes the impact each income component has on total inequality. The first measure captures the proportionate contribution of each income source to total inequality. Because this measure has some undesirable qualities (e.g., it violates the property of uniform additions), we include a second measure that represents the elasticity of total inequality with respect to the mean of an income source (Podder 1993; Podder and Chatterjee 2002; Shorrocks 1982). The elasticity for income source k indicates the average percentage change in total income inequality (G) associated with a percentage increase in the mean of income source k. Estimates account for both changes in the distribution of family structures in the population and the changing demographic composition (measured by racial composition and educational attainment) of the population.

Results suggest that cash welfare income became less effective in equalizing incomes over time. Looking at the adjusted results for the proportionate contribution to total inequality, we see that cash welfare income reduced the adjusted Gini coefficient for total family income by 1.4% in the welfare expansion era. In the AFDC reform eras, cash welfare income reduced total inequality by 1% in the first era and 0.9% in the second era. In the PRWORA era, the effectiveness of cash welfare income in offsetting income inequality dropped considerably. In the pre-recession PRWORA era, cash welfare income lowered total inequality by just 0.5%. In the post-recession PRWORA era, despite a sharp economic downturn, the efficacy of cash welfare income in moderating income inequality continued to weaken, with cash welfare income reducing income inequality by only 0.3%.

At the same time, tax and in-kind benefits became increasingly effective in offsetting total income inequality (the proportionate contribution of these benefits to total inequality became increasingly negative over time), until changing course in the final period. These benefits actually increased total income inequality by 1.6% in the welfare expansion era. Starting in the AFDC reform era I, tax and in-kind benefits began to reduce total income inequality by 0.1% and then by 1% in the AFDC II era. Following the passage of PRWORA, the effectiveness of tax and in-kind benefits in offsetting total income inequality increased, reducing total income inequality by 1.5%, but then in the final, post-recession era, tax and in-kind benefits increased total income inequality by 5.5%.

These changes are consistent with policy shifts at that time; welfare rolls decreased dramatically, and the concomitant expansion of tax and in-kind benefits redistributed aid to working poor families with higher incomes. As a result, the decimation of cash assistance left the most impoverished families without an economic safety net, decreasing the effectiveness of welfare programs in offsetting income inequality.

The adjusted elasticity results also reveal counterbalancing trends in the efficacy of welfare and in-kind benefits in reducing inequality. In the PRWORA era, cash welfare programs became less effective at moderating income inequality while tax and in-kind benefits initially became more effective before a reversal in the final period, when they began contributing to increased inequality among families. Prior to the passage of the PRWORA, a 1% increase in cash welfare was associated with 0.022%-0.026% reduction in the Gini coefficient for total family income (recall that a Gini coefficient of 0 is perfect equality). In the PRWORA era, the effect of a 1% increase in cash welfare income on the Gini coefficient for total family income decreased to −0.013% in the pre-recession period (a 41.9% drop) and −0.009% in the post-recession period (a 27.1% drop). Tax and in-kind benefits, on the other hand, became increasingly effective at moderating income inequality in the PRWORA pre-recession era, as indicated by the growing negative contribution of in-kind benefits to total inequality and the increasingly negative elasticity of in-kind benefits. However, in the final period, the proportionate contribution of tax and in-kind benefits to total inequality became positive while the elasticity followed the previous trend of becoming increasingly negative. This apparent contradiction is explained by the growing share of total income from tax and in-kind benefits in the final period. In calculating elasticity, the share of total income from the income source is subtracted from the proportionate contribution of that source to total inequality. Therefore, when the share of total income from tax and in-kind benefits grows, the elasticity of these benefits decreases (e.g. becomes increasingly negative), all else equal.

Cash welfare programs became less effective in offsetting other sources of income inequality and tax and in-kind benefits became more effective in the PRWORA era (particularly the pre-recession PRWORA era) in part due to the changing share of income from each of these sources. Looking at the top panel of table 1, we see that the share of total family income from cash welfare programs declined significantly, and the share from tax and in-kind benefits increased after welfare reform in 1996. In the AFDC I and II eras, 1.3% of total family income came from cash welfare programs, compared to 0.8% in the pre-recession era and 0.6% in the post-recession period. At the same time, the share of total income coming from tax and in-kind benefits increased steadily from 5.4% in the welfare expansion era to 7.4% in the AFDC reform era I, 9.6% in the AFDC reform era II, 11.7% in the pre-recession PRWORA era and 19% in the post-recession PRWORA era.

Although tax and in-kind benefits increased as a share of total income over the analysis period, they did not have the same redistributive effects as cash welfare because they are not as strongly negatively correlated with total income (see correlation coefficients in Table 1). While the correlation between total income and cash welfare declined from −0.35 to −0.15 over the analysis period, the correlation between tax and in-kind benefits and total income was −0.05 at its most negative in the PRWORA pre-recession era. As expected, this means that tax and in-kind benefits are not as equally distributed to the poorest families as are cash welfare benefits, and therefore contributed to growing income inequality in the final period. However, the increased share of total income from tax and in-kind benefits in the final period resulted in the increasingly negative elasticity of tax and in-kind benefits in this period.

Other income sources also shifted over this analysis period, contributing to greater inequality among families with children. Earned income became more unequally distributed, with its Gini coefficient rising from 0.3 5 in the welfare expansion era to 0.44 in the post-recession PRWORA era. Prior to the Great Recession, the share of income from investments rose and the correlation between investment income and total family income increased overall. Across the period of analysis, other forms of income such as income from pensions and retirement accounts, child support, alimony, survivor benefits, unemployment insurance, and worker’s compensation benefits increased slightly as a share of total family income and they became more strongly and positively correlated with total family income. However, the decline in the share of income from earned income and the growth in the share of income from tax and in-kind benefits in particular offset some of the changes which contributed to increasing inequality. This is because, although tax and in-kind benefits were more positively correlated with total income and less concentrated in the hands of the poorest poor than was cash welfare, tax and in-kind benefits were more weakly correlated with total income than earned income. As the share of total income from earned income declined over the study period from 87.7% in the welfare expansion era to 74.2% in the post-recession era, the share from tax and in-kind benefits increased from 5.4% to 19%, thus partially offsetting some of the overall trend toward increasing inequality among families. Overall, the declining share of total income from earned income and from cash welfare benefits was replaced by the growing share from tax and in-kind benefits, resulting in no overall change in total family inequality in the PRWORA eras. This challenges the prediction of H2: although there was a decline in the proportion of total income coming from cash welfare and a weakening negative association with family income as well as a growing share from tax and in-kind benefits, these changes (along with the declining share of total income from earned income), have resulted in stability in adjusted total family income inequality in the PRWORA eras.

6.3. State Policy Regimes and the Equalizing Effects of Welfare Income on Inequality in the PRWORA Era

We conducted our decomposition analysis separately in the five state clusters defined by their approach to welfare policy in order to assess whether a “race to the bottom” in the AFDC and TANF eras occurred across states and to analyze how the shifting balance between cash welfare and tax and in-kind benefits varied among states with different policy approaches and program generosity. Table 2 displays results for cash welfare, Table 3 for tax and in-kind benefits and Table 4 for combined cash welfare income and tax and in-kind benefits from these decompositions. Appendix tables 2A, 3A, and 4A display the results from these analyses (a) without any adjustments for family structure or demographic characteristics and (b) just with adjustments for family structure. Results from the other income components are available from the authors upon request. To analyze the overall effects of cash welfare and tax and in-kind benefits on total income inequality, we focus our discussion on the overall trends presented in Table 4, with reference to the specific results for cash welfare and tax and in-kind benefits when appropriate.

Table 2:

Decomposition of Gini Coefficient (Welfare Income) by State Policy Cluster and Welfare Era: 1968-2016 March Current Population Survey

| Family Structure and Demographics Adjusted Estimates | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Welfare Expansion 1968-1980 |

AFDC Reform Era I 1981-1987 |

AFDC Reform Era II 1988-1995 |

PWORA Era Pre- Recession 1996-2007 |

PWORA Era Post- Recession 2008-2016 |

|

| Components of Gini Decomposition | |||||

| Share of Income from Welfare Income (Sk) | |||||

| Minimal | 0.8% | 0.8% | 1.0% | 0.7% | 0.7% |

| Limited | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0.9% | 0.6% | 0.5% |

| Conservative | 0.6% | 0.6% | 0.7% | 0.4% | 0.4% |

| Generous | 1.6% | 1.8% | 1.8% | 1.0% | 0.7% |

| Integrated | 1.0% | 1.1% | 1.1% | 0.6% | 0.6% |

| Gini Coefficient for Welfare Income (Gk) | |||||

| Minimal | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 0.96 |

| Limited | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.96 | 0.97 |

| Conservative | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.97 |

| Generous | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.95 | 0.95 |

| Integrated | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.96 | 0.96 |

| Correlation Coefficient for Welfare Income and Total Income (Rk) | |||||

| Minimal | −0.24 | −0.07 | −0.17 | −0.22 | −0.24 |

| Limited | −0.26 | −0.17 | −0.21 | −0.18 | −0.15 |

| Conservative | −0.34 | −0.28 | −0.26 | −0.23 | −0.13 |

| Generous | −0.40 | −0.32 | −0.25 | −0.18 | −0.11 |

| Integrated | −0.41 | −0.41 | −0.31 | −0.26 | −0.18 |

| Estimated Impact of Welfare Income on Total Inequality | |||||

| Proportionate Contribution to Total Inequality | |||||

| Minimal | −0.6% | −0.2% | −0.5% | −0.5% | −0.5% |

| Limited | −0.7% | −0.4% | −0.6% | −0.4% | −0.3% |

| Conservative | −0.7% | −0.6% | −0.6% | −0.4% | −0.2% |

| Generous | −2.1% | −1.8% | −1.4% | −0.6% | −0.2% |

| Integrated | −1.5% | −1.5% | −1.1% | −0.5% | −0.3% |

| Elasticity | |||||

| Minimal | −0.014 | −0.010 | −0.016 | −0.013 | −0.013 |

| Limited | −0.015 | −0.012 | −0.014 | −0.010 | −0.008 |

| Conservative | −0.013 | −0.012 | −0.013 | −0.008 | −0.006 |

| Generous | −0.037 | −0.036 | −0.032 | −0.016 | −0.010 |

| Integrated | −0.025 | −0.026 | −0.022 | −0.011 | −0.087 |

Table 3:

Decomposition of Gini Coefficient (Tax and In-Kind Benefits) by State Policy Cluster and Welfare Era: 1968-2016 March Current Population Survey

| Family Structure and Demographics Adjusted Estimates | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Welfare Expansion 1968-1980 |

AFDC Reform Era I 1981-1987 |

AFDC Reform Era II 1988- 1995 |

PWORA Era Pre- Recession 1996- 2007 |

PWORA Era Post- Recession 2008- 2016 |

|

|

Components of Gini

Decomposition Share of Income from Tax and In-kind Benefits (Sk) | |||||

| Minimal | 7.4% | 12.0% | 14.0% | 15.7% | 22.7% |

| Limited | 6.5% | 7.4% | 9.5% | 11.5% | 18.8% |

| Conservative | 4.3% | 5.6% | 7.9% | 8.9% | 16.4% |

| Generous | 4.8% | 6.3% | 8.9% | 11.9% | 19.2% |

| Integrated | 4.4% | 4.9% | 6.3% | 6.9% | 13.5% |

| Gini Coefficient for Tax and In-kind Benefits (Gk) | |||||

| Minimal | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.76 | 0.72 | 0.65 |

| Limited | 0.80 | 0.82 | 0.79 | 0.75 | 0.69 |

| Conservative | 0.78 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.71 |

| Generous | 0.80 | 0.84 | 0.80 | 0.76 | 0.68 |

| Integrated | 0.79 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.82 | 0.74 |

| Correlation Coefficient for Tax and In-kind Benefits and Total Income (Rk) | |||||

| Minimal | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.20 |

| Limited | 0.16 | 0.03 | −0.01 | −0.05 | 0.12 |

| Conservative | 0.11 | −0.08 | −0.07 | −0.12 | 0.09 |

| Generous | 0.06 | −0.11 | −0.08 | −0.05 | 0.13 |

| Integrated | 0.09 | −0.20 | −0.18 | −0.18 | 0.01 |

| Estimated Impact of Tax and In-kind Benefits on Total Inequality | |||||

| Proportionate Contribution to Total Inequality | |||||

| Minimal | 4.3% | 6.7% | 3.5% | 2.0% | 9.9% |

| Limited | 2.8% | 0.5% | −0.3% | −1.4% | 5.2% |

| Conservative | 1.4% | −1.3% | −1.7% | −3.2% | 3.8% |

| Generous | 0.8% | −1.8% | −1.9% | −1.4% | 5.6% |

| Integrated | 1.1% | −2.9% | −3.4% | −3.5% | 4.2% |

| Elasticity | |||||

| Minimal | −0.031 | −0.052 | −0.104 | −0.137 | −0.128 |

| Limited | −0.037 | −0.069 | −0.098 | −0.129 | −0.136 |

| Conservative | −0.029 | −0.070 | −0.097 | −0.121 | −0.126 |

| Generous | −0.040 | −0.081 | −0.108 | −0.133 | −0.136 |

| Integrated | −0.033 | −0.078 | −0.097 | −0.103 | −0.130 |

Table 4:

Decomposition of Gini Coefficient (Cash Welfare and Tax and In-kind Benefits) by State Policy Cluster and Welfare Era: 1968-2016 March Current Population Survey

| Family Structure and Demographics Adjusted Estimates | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Welfare Expansion 1968- 1980 |

AFDC Reform Era I 1981- 1987 |

AFDC Reform Era II 1988- 1995 |

PWORA Era Pre- Recession 1996- 2007 |

PWORA Era Post- Recession 2008- 2016 |

|

| Components of Gini Decomposition | |||||

| Share of Income from Welfare and Tax and In-kind Benefits (Sk) | |||||

| Minimal | 8.2% | 12.8% | 15.0% | 16.4% | 23.4% |

| Limited | 7.3% | 8.2% | 10.4% | 12.1% | 19.4% |

| Conservative | 4.9% | 6.3% | 8.6% | 9.4% | 16.8% |

| Generous | 6.4% | 8.1% | 10.7% | 13.0% | 19.9% |

| Integrated | 5.4% | 6.0% | 7.4% | 7.5% | 14.0% |

| Gini Coefficient for Welfare and Tax and In-kind Benefits (Gk) | |||||

| Minimal | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.76 | 0.71 | 0.65 |

| Limited | 0.80 | 0.82 | 0.79 | 0.75 | 0.68 |

| Conservative | 0.79 | 0.82 | 0.80 | 0.78 | 0.71 |

| Generous | 0.81 | 0.84 | 0.80 | 0.75 | 0.68 |

| Integrated | 0.80 | 0.85 | 0.84 | 0.82 | 0.74 |

| Correlation Coefficient for Welfare and Tax and In-kind Benefits and Total Income (Rk) | |||||

| Minimal | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.18 |

| Limited | 0.11 | 0.01 | −0.03 | −0.06 | 0.11 |

| Conservative | 0.05 | −0.10 | −0.09 | −0.13 | 0.09 |

| Generous | −0.07 | −0.16 | −0.12 | −0.06 | 0.12 |

| Integrated | −0.02 | −0.25 | −0.21 | −0.19 | 0.00 |

| Estimated Impact of Welfare and Tax and In-kind Benefits on Total Inequality | |||||

| Proportionate Contribution to Total Inequality | |||||

| Minimal | 3.7% | 6.6% | 3.0% | 1.5% | 9.3% |

| Limited | 2.2% | 0.1% | −0.8% | −1.7% | 5.0% |

| Conservative | 0.8% | −1.9% | −2.3% | −3.6% | 3.6% |

| Generous | −1.3% | −3.6% | −3.3% | −2.0% | 5.4% |

| Integrated | −0.4% | −4.3% | −4.5% | −4.0% | 0.1% |

| Elasticity | |||||

| Minimal | 0.037 | −0.062 | −0.120 | −0.149 | −0.140 |

| Limited | −0.052 | −0.081 | −0.112 | −0.138 | −0.144 |

| Conservative | −0.041 | −0.082 | −0.109 | −0.129 | −0.132 |

| Generous | −0.078 | −0.118 | −0.140 | −0.150 | −0.145 |

| Integrated | −0.058 | −0.104 | −0.119 | −0.115 | −0.139 |

Four important findings emerge from our decomposition of total income inequality by welfare regime era and state policy cluster. First, state differences in welfare policies are related to historic variation in family income inequality. In the welfare expansion era, combined cash welfare income and tax and in-kind benefits made the greatest contribution to offsetting inequality in generous and integrated states. Looking at the adjusted estimates for the proportionate contribution to total inequality in table 4, results show that cash welfare income and tax and in-kind benefits reduced the Gini coefficient by 1.3% in generous states and by 0.4% in the integrated states in the first period. In the other state clusters, cash welfare and tax and in-kind benefits actually increased total inequality by 0.8-3.7%.

As shown in the elasticity results, a percentage increase in cash welfare and tax and in-kind benefits spending was associated with a 0.078% decrease in income inequality in the generous state policy cluster, but a 0.041%, 0.052%, and 0.058% decrease in the conservative, limited, and integrated state clusters, respectively. By contrast, in the minimal state cluster, a percentage increase in these benefits was associated with a 0.037% increase in income inequality.

Interestingly, the minimal states had the largest share of income from combined cash welfare and tax and in-kind benefits in the welfare expansion era. Looking at the adjusted results in the top panel of Table 4, results show that welfare and tax and in-kind benefits accounted for 8.2% of total income in the minimal states, 7.3% in the limited states, 6.4% in the generous states, 5.4% in the integrated states and 4.9% in the conservative states. However, when cash welfare is separated from tax and in-kind benefits, it becomes clear that the larger share of income from cash welfare and tax and in-kind benefits in the minimal and limited states is due to tax and in-kind benefits rather than cash welfare (Tables 2 and 3). While tax and in-kind benefits represented about 75% of the combined total in the generous states in the welfare expansion era, they represented between 88 and 90% of the total in the limited, conservative and minimal states (and 82% of the total in the integrated states). If comparing cash welfare benefits alone in the different states in the welfare expansion era (Table 2), they accounted for 1.6% of total income in the generous state policy cluster, but between 0.6% (conservative cluster) and 1.0% (integrated cluster) in the other clusters. In the initial period of AFDC reform, cash welfare income constituted 1.8% of total income in generous states compared to 0.6%-1.1% in the other state clusters.

Combined cash welfare and tax and in-kind benefits were also more negatively correlated with total income in the generous and integrated states in the first three periods, compared to the other state clusters (Table 4). In the generous states, the correlation ranged from −0.07 to −0.16 and in the integrated states from −0.02 −0.25 in the first three periods. In comparison, in the minimal and limited states, the correlation ranged from 0.20 to −0.03 and in the conservative states it ranged from 0.05 to −0.10. For these reasons, combined cash welfare and tax and in-kind benefits in the generous and integrated states have historically been better at ameliorating income inequality among families with children.

Second, we find that the efficacy of combined cash welfare and tax and in-kind benefits in reducing family income inequality in the states in the generous and integrated policy clusters began to weaken in the PRWORA pre-recession era. In Table 4, results show that the contribution of cash welfare and tax and in-kind benefits to the reduction of total inequality fell by 38.5% in the generous states, declining from −3.3% in the latter period of AFDC reform to −2.0% in the pre-recession PRWORA era. In the integrated states, it fell by 11.3%, declining from −4.5% to −4.0%. The elasticity of cash welfare and tax and in-kind benefits fell by 3.5% in the integrated states, decreasing from −0.119 to −0.115, but the elasticity of cash welfare and tax and in-kind benefits actually increased by 7% (from −0.140 to −0.150) in the generous states. This is explained by the growing share of total income from cash welfare and tax and in-kind benefits between these two periods, from 10.7% to 13.0% in the generous states. Based on the elasticity measures, the cash welfare and tax and in-kind benefits of generous states remained more effective in offsetting inequality than in the minimal, limited and conservative states, but the differences among these states shrank. Based on the estimates of the proportionate contributions of cash welfare and tax and in-kind benefits to total inequality, the generous states actually became less effective at reducing overall income inequality than the conservative states and the difference between the generous states and the limited and minimal states shrank in the PRWORA pre-recession era. These findings are consistent with a “race to the bottom” hypothesis (H3B).

One reason that combined cash welfare and tax and in-kind benefits became less effective in offsetting total inequality in the PRWORA era in the generous and integrated states is that combined cash welfare and tax and in-kind benefits became less redistributive (i.e., they were less concentrated amongst the poorest families in the PRWORA era than in the AFDC era). To see this, we can compare the strength of the Gini coefficient for combined cash welfare and tax and in-kind benefits and the negative correlation between combined cash welfare and tax and in-kind benefits and total family income for the eras immediately preceding and following the passage of the PRWORA. Together, these changes show that combined cash welfare and tax and in-kind benefits became less concentrated in the hands of the poorest poor in the generous and integrated states with the PRWORA. The estimates of the Gini coefficient for combined cash welfare and tax and in-kind benefits declined by 6.0% in the generous states and 2.9% in the integrated states and the correlation coefficient declined by 46.1% in the generous states and 6.8% in the integrated states.

Third, we find that the effectiveness of combined cash welfare and tax and in-kind benefits in offsetting inequality from other income sources increased in the PRWORA era in the conservative, limited, and minimal state clusters, but that this change was due entirely to tax and in-kind benefits and not cash welfare. The proportionate contribution of combined cash welfare and tax and in-kind benefits to offsetting total inequality increased in strength between the latter period of AFDC reform and the pre-recession PRWORA era in these states. Results in Table 4 illustrate that the proportionate contribution of cash welfare and tax and in-kind benefits to offsetting inequality strengthened from −0.8% to−1.7% (107.2% change) in the limited states and from −2.3% to −3.6% (51.7% change) in the conservative states. In the minimal states, combined cash welfare and tax and in-kind benefits positively contributed to overall income inequality in the period immediately preceding and following the passage of the PRWORA but, following the passage of the PRWORA, the positive proportionate contribution of these combined benefits to total inequality declined in the minimal states from 3.0% to 1.5% (50.3% change). At the same time, the marginal effect of combined cash welfare and tax and in-kind benefits on income inequality among families with children also became increasingly negative (minimal states increased by 24.4%, limited states increased by 23.7%, and conservative states increased by 18.2%).

The increased effectiveness of combined cash welfare and tax and in-kind benefits in offsetting total inequality in the PRWORA era in the minimal, limited and conservative states is due entirely to changes in tax and in-kind benefits between these two periods. Tax and in-kind benefits became more effective in the minimal, limited and conservative states at offsetting total income inequality with the PRWORA because these benefits became more negatively (or less positively in the case of the minimal states) correlated with total income (i.e., they became more concentrated amongst the poorest families in the PRWORA era than in the AFDC era in these states).

At the same time, cash welfare became less effective across all states in offsetting total inequality, with the exception of the minimal states where it remained constant at −0.5%. The marginal contribution of cash welfare income to income inequality also declined in all states. This can be explained by the declining share of total income from cash welfare in all states (with between a 28.2% drop in the share of total income coming from cash welfare in the minimal states to a 44.0% drop in share in the integrated states) as well as the weakening negative correlation between cash welfare and total income in all states except the minimal states (i.e., cash welfare became less concentrated amongst the poorest families in the PRWORA era than in the AFDC reform era II in these states). It is only because of the growing share of total income from tax and in-kind benefits for the PRWORA era and the declining positive correlation or growing negative correlation between tax and in-kind benefits and total income that there was overall growth in the effectiveness of combined cash welfare and tax and in-kind benefits in offsetting total inequality in the PRWORA era in the minimal, limited and conservative states.

Fourth, our results for the pre- and post-recession periods show that the “race to the bottom” in the PRWORA era eroded the role of cash welfare and tax and in-kind benefits in ameliorating income inequality even as the deepest recession in the post-World War II era raised poverty and unemployment rates (Sheely 2012). The earlier trend toward the declining effectiveness of cash welfare and tax and in-kind benefits in offsetting total inequality continued into the post-recession PRWORA era in the generous and integrated states, and the minimal, limited, and conservative states experienced a reversal towards declining effectiveness in offsetting inequality between the pre-recession and post-recession eras. In all policy clusters, combined cash welfare and tax and in-kind benefits positively contributed to total inequality by the final period. In the integrated states, the proportionate contribution of cash welfare and tax and in-kind benefits to offsetting total inequality changed from −4.0% to 0.1% (102.7%), in the generous states from −2.0% to 5.4% (368.7%), in the conservative states from −3.6% to 3.6% (200%), in the limited states from −1.7% to 5.0% (389%), and in the minimal states from 1.5% to 9.3% (531.1%).

The declining effectiveness of cash welfare and tax and in-kind benefits in the post-recession era is attributable to the fact that benefits became positively correlated with total income and more equally distributed (i.e., they became less concentrated amongst the poorest families in the post-recession era). The share of total income from tax and in-kind and cash welfare benefits actually increased in all states in the post-recession era, it is just that the benefits became less concentrated in the hands of the poorest poor and therefore less effective at weakening total inequality.

One caveat is that although we find a decline in the proportionate contribution of tax and in-kind and cash welfare benefits to offsetting total inequality in all states in the post-recession era, we also find a growing marginal effect of cash welfare and tax and in-kind benefits on income inequality in some state clusters (namely the limited, conservative, and integrated clusters). In other words, an additional 1% increase in the amount spent on cash welfare and tax and in-kind benefits in the post-recession era yielded a greater percentage effect on total inequality in the post-recession, compared to the pre-recession, era in these state clusters. This is explained by the growing share of total income from cash welfare and tax and in-kind benefits between these two periods. When the share of total income from tax and in-kind and cash welfare benefits grows, the elasticity of these benefits decreases (e.g. becomes increasingly negative), all else equal. The limited, conservative, and integrated clusters experienced the greatest increase in the share of total income from cash welfare and tax and in-kind benefits in the post-recession era.

7. Discussion and Conclusion

Income inequality in the United States surpasses all other rich industrialized nations, and has increased at a faster rate (Smeeding, 2005). Our study documented the growth of income inequality among families with children from 1968-2017. This growth in inequality was greater in the period immediately following the passage of the PRWORA and following the recovery from the Great Recession than in the earlier era of welfare expansion (1968-1980) (H1), and our results suggest that this is related to changes in welfare policy over this period, and the passage of PRWORA in particular. We found a declining proportion of total income from cash welfare and a weakening negative association between cash welfare and total family income following the passage of the PRWORA.

The decline in cash benefits from TANF and the expansion of non-cash social safety net programs shifted support away from the most disadvantaged populations, including those without work, and towards working poor families with higher incomes (Moffitt, 2015). This is reflected in our finding that the share of income from cash welfare declined over this period and that welfare became less concentrated among the poorest families (H2). These findings are consistent with previous research that has pointed to falling incomes and unstable employment at the bottom of the distribution and the growth of families in extremely deep $2-a-day poverty after welfare reform (Edin & Shaefer, 2015; Shaefer & Edin, 2013). However, the weakening role of cash assistance in addressing family income inequality has been partially offset by the expansion of other programs that offer tax and in-kind benefits, as well as a declining share of total income from earned income. The result was relative stability in adjusted total family income inequality in the PRWORA eras, challenging the prediction of rising total family inequality following the passage of the PRWORA (H2). Nevertheless, it is important to keep in mind that in-kind benefits are not equivalent to cash. The flexibility of cash is vital when low-income families face emergencies or unexpected expenses that do not fall under the restricted spending categories of in-kind benefits. Cash can also be saved or invested in assets that help to lift people out of poverty (Edin & Shaefer, 2015; Bogle et al, 2016).

We also investigated state-level differences in welfare policy and the implications for family income inequality within states. We analyzed changes in total family income inequality as well as changes in the effectiveness of welfare in offsetting total inequality across state clusters based on policy regimes (Meyers, Gornick and Peck 2001). Looking historically over a period of 48 years, we found that the effectiveness of welfare spending in offsetting total inequality was related to differences in welfare policy between state clusters. In the welfare expansion (1968-1980) and first AFDC reform era (1981-1987) in particular, welfare represented a larger share of total family income and was more effective in reducing total income inequality in the generous states compared to the limited and minimal states. However, following the passage of PRWORA, the effectiveness of welfare policies in offsetting total income inequality declined in the generous and integrated states while the effectiveness of welfare policies increased in the conservative, limited and minimal states due to the growth of tax and in-kind benefits as a share of total income. Despite growing state control of the welfare system under PRWORA, we observed decreasing variation across state clusters in the effectiveness of welfare in offsetting total income inequality in the final post-recession PRWORA era, with declines across the board in welfare’s ability to reduce total income inequality, consistent with a notion of a “race to the bottom” (H3B) (Peterson and Rom 1990). The large gap between states that have historically had generous welfare policies and states with more limited approaches to welfare policy closed following the passage of PRWORA.

Three notable limitations of this study should be considered in evaluating the results. First, we rely on self-reported income measures. Future research could address the potential bias inherent in self-reports of income (e.g., social desirability bias) by instead using administrative tax records to measure family income. Relatedly, we necessarily rely on imputed measures of in-kind benefits and tax credits where the CPS did not collect this information directly (e.g., historical measures of SNAP, WIC, housing assistance, and some tax credits). Although this introduces some uncertainty into our estimates, prior research suggests that results are robust to the exclusion of the imputed data (Fox et al. 2015).

Second, our definition of cohabiting families excludes same-sex cohabiting families due to limitations in historical measures of family structure in the CPS. Although eligibility for most federal benefits relies on a legal definition of the family that excludes both homogamous and heterogamous cohabiters, this is an important consideration. Given the diversity of family forms in the U.S. and proposals to include cohabiters for determining eligibility of government benefits, future research should examine changing family inequality trends in different family types.

Third, we combine in-kind and tax benefits in our analysis in order to contrast them with cash welfare, but they may have distinct effects. Future research should analyze how these income sources uniquely contribute to overall family income inequality. Our data uses estimates of the Earned Income Tax Credit based on a simulation that assumes that all eligible families receive the credit. This may overestimate the impact of the EITC on income inequality. Nevertheless, this is likely to be offset by the under-reporting of other benefits (Fox et al. 2015). Given the aggregate reporting of the EITC and other in-kind resources, we are unlikely to overstate the impact of all government benefits and so there are some advantages to our aggregate approach.

We found that United States’ direct-income-transfer policies, which do a poorer job of redistributing wealth compared to other nations, particularly at the lower range of the income distribution (Smeeding, 2005), contribute to growing income inequality among families with children. Yet it is important to remember that welfare’s weakening role as an equalizing agent only tells part of the story about the welfare state and the social safety net. In-kind benefits, such as health insurance and education, and near-cash transfers, such as food stamps and housing allowances, also provide important support for poor families. Tax programs, such as the EITC and CTC, have also become an increasingly important component of the social safety net. Once these sources of non-cash support are taken into account, inequality at the bottom of the income distribution is reduced (Garfinkel, Rainwater, & Smeeding, 2006), and we found no increase in total family inequality following the passage of PRWORA in the estimates adjusted for tax and in-kind benefits, changes in family structure and population demographics. This underscores the importance of updated poverty measures such as the Supplemental Poverty Measure, which takes these benefits into account and gives a more comprehensive picture of the economic resources that a family can access.

Nevertheless, cash assistance plays a vital role in our social safety net. While tax and in-kind benefits provide expanded support for working families, those with significant barriers to work are in a precarious position in light of lifetime limits to welfare and stringent eligibility requirements. Indeed, following welfare reform in 1996, research has documented a growing share of single mothers who are disconnected from both earnings and welfare (Loprest, 2011; Turner, Danziger, & Seefeldt, 2006) and the poorest children have fallen further down in the income distribution (Joo 2011). Cash provides families with the flexibility to handle unexpected expenses, or for costs that are not covered by in-kind benefits (Shaefer et al., 2015). Our study suggests that cash welfare not only plays a much smaller role in augmenting family income, it is also no longer effective as an equalizing agent. This study therefore deepens our understanding about the role of cash assistance in family income inequality and contributes to the research evidence supporting the need for direct-income-transfer policies that provide more flexible income sources to replace cash welfare, particularly for the most impoverished and vulnerable families

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by NICHD of the National Institutes of Health under award number P2C HD050924.

APPENDIX

Appendix Table 1A:

Decomposition of Gini Coefficient by Welfare Era: 1968-2016 March Current Population Survey

| Unadjusted

Estimates |

Family Structure

Adjusted Estimates |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Welfare Expansion 1968-1980 |

AFDC Reform Era I 1981-1987 |

AFDC Reform Era II 1981-1995 |

PWORA Era Pre- Recession 1996-2007 |

PWORA Era Post- Recession 2008-2016 |

Welfare Expansion 1968-1980 |

AFDC Reform Era I 1981-1987 |

AFDC Reform Era II 1981-1995 |

PWORA Era Pre- Recession 1996-2007 |

PWORA Era Post- Recession 2008-2016 |

|

| Components of Gini Decomposition | ||||||||||

| Share of Income (Sk) | ||||||||||

| Earned | 87.5% | 84.7% | 83.6% | 83.9% | 80.5% | 88.5% | 87.0% | 86.6% | 86.7% | 84.0% |

| Welfare | 1.3% | 1.4% | 1.3% | 0.7% | 0.5% | 1.0% | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0.4% | 0.3% |

| Investment | 1.7% | 2.3% | 2.2% | 2.6% | 2.1% | 1.7% | 2.4% | 2.4% | 2.8% | 2.3% |

| Other Income | 4.3% | 4.9% | 5.0% | 4.6% | 5.0% | 4.2% | 4.7% | 4.7% | 4.3% | 4.6% |

| In Kind | 5.2% | 6.7% | 7.9% | 8.2% | 11.8% | 4.6% | 5.1% | 5.5% | 5.8% | 8.7% |

| Gini Coefficient (Gk) | ||||||||||

| Total Income | 0.30 | 0.32 | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.32 | 32.4% |

| Earned | 0.36 | 0.41 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.45 | 0.34 | 0.37 | 0.38 | 0.39 | 41.2% |

| Welfare | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 97.5% |

| Investment | 0.96 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 95.0% |

| Other Income | 0.86 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.86 | 85.9% |

| In Kind | 0.80 | 0.83 | 0.81 | 0.79 | 0.74 | 0.80 | 0.84 | 0.83 | 0.82 | 77.5% |

| Correlation (Rk) | ||||||||||

| Earned | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 91.4% |

| Welfare | −0.39 | −0.37 | −0.35 | −0.31 | −0.26 | −0.38 | −0.33 | −0.32 | −0.30 | −25.9% |

| Investment | 0.54 | 0.53 | 0.58 | 0.61 | 0.66 | 0.53 | 0.51 | 0.54 | 0.58 | 63.0% |

| Other Income | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.12 | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 9.6% |

| In Kind | 0.08 | −0.08 | −0.15 | −0.19 | −0.06 | 0.09 | −0.10 | −0.21 | −0.27 | −14.1% |

| Estimated Impact of Income Components on Total Inequality | ||||||||||

| Proportionate Contribution to Total Inequality | ||||||||||

| Earned | 97.9% | 98.7% | 99.4% | 98.6% | 96.5% | 97.5% | 98.5% | 99.2% | 98.7% | 97.7% |

| Welfare | −1.7% | −1.5% | −1.3% | −0.6% | −0.4% | −1.3% | −0.9% | −0.8% | −0.4% | −0.3% |

| Investment | 2.9% | 3.9% | 3.9% | 4.5% | 4.0% | 3.0% | 4.1% | 4.1% | 4.8% | 4.3% |

| Other Income | −0.3% | 0.2% | 1.1% | 1.2% | 1.5% | −0.4% | −0.2% | 0.7% | 0.9% | 1.2% |

| In Kind | 1.1% | −1.4% | −3.0% | −3.7% | −1.6% | 1.1% | −1.5% | −3.2% | −4.0% | −2.9% |

| Elasticity | ||||||||||

| Earned | 0.105 | 0.140 | 0.158 | 0.147 | 0.160 | 0.091 | 0.115 | 0.125 | 0.120 | 0.136 |

| Welfare | −0.030 | −0.028 | −0.025 | −0.013 | −0.008 | −0.023 | −0.017 | −0.015 | −0.008 | −0.006 |

| Investment | 0.013 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.019 | 0.018 | 0.013 | 0.016 | 0.017 | 0.020 | 0.020 |

| Other Income | −0.046 | −0.047 | −0.040 | −0.035 | −0.035 | −0.046 | −0.049 | −0.041 | −0.034 | −0.035 |

| In Kind | −0.042 | −0.080 | −0.109 | −0.119 | −0.135 | −0.035 | −0.065 | −0.087 | −0.097 | −0.116 |

Appendix Table 2A:

Decomposition of Gini Coefficient (Welfare Income) by State Policy Cluster and Welfare Era: 1968-2016 March Current Population Survey

| Unadjusted

Estimates |

Family Structure

Adjusted Estimates |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Welfare Expansion 1968-1980 |

AFDC Reform Era I 1981-1987 |

AFDC Reform Era II 1981-1995 |

PWORA Era Pre- Recession 1996-2007 |

PWORA Era Post- Recession 2008-2016 |

Welfare Expansion 1968-1980 |

AFDC Reform Era I 1981-1987 |

AFDC Reform Era II 1981-1995 |

PWORA Era Pre- Recession 1996-2007 |

PWORA Era Post- Recession 2008-2016 |

|

| Components of Gini Decomposition | ||||||||||

| Share of Income from Welfare Income (Sk) | ||||||||||

| Minimal | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0.9% | 0.6% | 0.5% | 0.7% | 0.5% | 0.6% | 0.4% | 0.4% |

| Limited | 0.9% | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0.5% | 0.4% | 0.7% | 0.5% | 0.5% | 0.3% | 0.3% |

| Conservative | 0.6% | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0.4% | 0.4% | 0.5% | 0.5% | 0.4% | 0.3% | 0.3% |

| Generous | 1.8% | 1.9% | 1.7% | 0.9% | 0.6% | 1.3% | 1.2% | 1.0% | 0.5% | 0.4% |

| Integrated | 1.1% | 1.4% | 1.1% | 0.5% | 0.4% | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0.6% | 0.3% | 0.3% |

| Gini Coefficient for Welfare Income (Gk) | ||||||||||

| Minimal | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.98 |

| Limited | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.98 |

| Conservative | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.98 |

| Generous | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.94 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.97 |

| Integrated | 0.95 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.98 |

| Correlation Coefficient for Welfare Income and Total Income (Rk) | ||||||||||

| Minimal | −0.27 | −0.13 | −0.22 | −0.29 | −0.29 | −0.28 | −0.15 | −0.24 | −0.29 | −0.32 |

| Limited | −0.30 | −0.24 | −0.27 | −0.26 | −0.26 | −0.29 | −0.25 | −0.30 | −0.28 | −0.26 |

| Conservative | −0.40 | −0.38 | −0.36 | −0.34 | −0.26 | −0.36 | −0.33 | −0.32 | −0.30 | −0.23 |

| Generous | −0.44 | −0.43 | −0.40 | −0.34 | −0.26 | −0.43 | −0.39 | −0.36 | −0.32 | −0.24 |

| Integrated | −0.45 | −0.48 | −0.44 | −0.38 | −0.32 | −0.44 | −0.46 | −0.41 | −0.38 | −0.31 |

| Estimated Impact of Welfare Income on Total Inequality | ||||||||||

| Proportionate Contribution to Total Inequality | ||||||||||

| Minimal | 0.7% | −0.3% | −0.6% | −0.5% | −0.4% | −0.6% | −0.3% | −0.5% | −0.4% | −0.3% |

| Limited | −0.8% | −0.6% | −0.7% | −0.4% | −0.3% | −0.6% | −0.4% | −0.5% | −0.3% | −0.2% |

| Conservative | −0.9% | −0.9% | −0.8% | −0.4% | −0.3% | −0.6% | −0.5% | −0.5% | −0.3% | −0.2% |

| Generous | −2.5% | −2.3% | −1.9% | −0.8% | −0.4% | −1.9% | −1.5% | −1.2% | −0.5% | −0.3% |

| Integrated | −1.7% | −1.9% | −1.5% | −0.6% | −0.4% | −1.3% | −1.2% | −0.8% | −0.4% | −0.3% |

| Elasticity | ||||||||||

| Minimal | −0.015 | −0.011 | −0.015 | −0.011 | −0.009 | −0.013 | −0.008 | −0.011 | −0.008 | −0.007 |

| Limited | −0.016 | −0.014 | −0.015 | −0.009 | −0.007 | −0.013 | −0.009 | −0.010 | −0.006 | −0.005 |

| Conservative | −0.015 | −0.017 | −0.016 | −0.008 | −0.007 | −0.011 | −0.010 | −0.009 | −0.005 | −0.004 |

| Generous | −0.042 | −0.042 | −0.036 | −0.017 | −0.010 | −0.033 | −0.027 | −0.022 | −0.010 | −0.006 |

| Integrated | −0.028 | −0.033 | −0.026 | −0.011 | −0.008 | −0.021 | −0.019 | −0.014 | −0.007 | −0.005 |

Appendix Table 3A:

Decomposition of Gini Coefficient (In-Kind Income) by State Policy Cluster and Welfare Era: 1968-2016 March Current Population Survey

| Unadjusted

Estimates |

Family Structure

Adjusted Estimates |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Welfare Expansion 1968-1980 |

AFDC Reform Era I 1981-1987 |

AFDC Reform Era II 1981-1995 |

PWORA Era Pre- Recession 1996-2007 |

PWORA Era Post- Recession 2008-2016 |

Welfare Expansion 1968-1980 |

AFDC Reform Era I 1981-1987 |

AFDC Reform Era II 1981-1995 |

PWORA Era Pre- Recession 1996-2007 |

PWORA Era Post- Recession 2008-2016 |

|

| Components of Gini Decomposition | ||||||||||