The emergence of a novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, in December, 2019, has had devastating consequences on health, social, and economic systems around the world. Of the estimated 115 million people (about 10% with diabetes) who have been infected with SARS-CoV-2, more than 2·5 million patients had died due to COVID-19 at the time of writing (data from the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Research Center). People with diabetes and related comorbidities are at increased risk of severe COVID-19 complications, and COVID-19-related mortality in this population is two to three times higher than that in people without diabetes.1 Various mechanisms might explain why patients with diabetes are over-represented among those admitted to hospital with severe COVID-19 and have an increased risk for death. Metabolic inflammation is common in patients with diabetes and predisposes them to an enhanced release of cytokines.2 For COVID-19, a cytokine storm has been implicated in the multiorgan failure reported in patients with severe disease. Inflammatory-driven processes are probably primary drivers of coagulopathy in COVID-19. Venous thromboembolism, arterial thrombosis, and thrombotic microangiopathy substantially contribute to increased morbidity and mortality in patients with COVID-19.3 The chronic inflammation and hypercoagulable state common in diabetes could contribute to the high mortality risk associated with COVID-19 and diabetes.

Glucose-lowering drugs used in the treatment of patients with diabetes might have significant effects on COVID-19 pathophysiology, potentially affecting the risk of progression to severe disease and mortality. In The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, Kamlesh Khunti and colleagues4 report COVID-19 mortality rates for patients with type 2 diabetes on different glucose-lowering therapies, in an observational nationwide study in England. The pre-infection prescription of glucose-lowering therapies and risk of COVID-19 mortality was analysed in 2·85 million people with type 2 diabetes, covering almost the whole population of people with type 2 diabetes who were registered with a general practice in England (irrespective of whether or not patients had been admitted to hospital). Overall, a COVID-19-related death occurred in 13 479 (0·5%) of the 2 851 465 patients during the study period (Feb 16 to Aug 31, 2020). Metformin, SGLT2 inhibitors, and sulfonylureas were associated with reduced risks of the COVID-19-related mortality, whereas insulin and DPP-4 inhibitors were associated with increases in risk; neutral results were found for GLP-1 receptor agonists and thiazolidinediones. Unfortunately, data were not available to allow the researchers to identify when the drugs were stopped during the progression of COVID-19, and it was not possible to establish whether the combination therapies that are widely used to control diabetes in England had any effect on mortality.

Khunti and colleagues' findings4 are in line with a recent update from the nationwide CORONADO study in France,5 which also showed that, in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 and diabetes, metformin use was associated with a decrease and insulin was associated with an increase in mortality risk. A significantly reduced mortality rate associated with the use of metformin (odds ratio 0·62 [95% CI 0·43–0·89]) was also reported in a recent meta-analysis of five studies6 including 8121 patients with diabetes who were admitted to hospital for COVID-19. The findings of these studies, including the study by Khunti and colleagues,4, 5, 6 are probably related at least in part to confounding by indication, as metformin is used early in the disease course of type 2 diabetes, whereas insulin is initiated later. The use of SGLT2 inhibitors compared with DPP-4 inhibitors was associated with significantly lower mortality risk associated with COVID-19 in both Khunti and colleagues' study in England4 and another recent study in Denmark.7 However, in Khunti and colleagues' study,4 47% of the patients receiving a DPP-4 inhibitor were aged 70 years or older, compared with only 18% taking an SGLT2 inhibitor. Patients with an eGFR between 15 mL/min per 1·73 m2 and less than 60 mL/min per 1·73 m2 had a very high mortality risk in univariate analyses (hazard ratio 3·7 [95% CI 3·5–3·9] for 45 to <60 mL/min per 1·73 m2 to 9·1 [8·4–9·9] for 15 to <30 mL/min per 1·73 m2). Notably, almost 25% of patients on a DPP-4 inhibitor had eGFR of less than 60 mL/min per 1·73 m2, compared with only 4·1% of patients on an SGLT2 inhibitor.

How might these findings inform clinical practice? On the basis of evidence from smaller studies, Lim and colleagues8 recommended that DPP-4 inhibitors be used across a broad spectrum of COVID-19 severity, but that SGLT2 inhibitors should only be used with caution, and metformin should be stopped in severe cases. Because positive results with respect to all-cause mortality have previously been reported for metformin and SGLT2 inhibitors,9 withdrawal or non-use of these drugs could have a negative effect on the prognosis of patients with type 2 diabetes and COVID-19. Given the large cohort in Khunti and colleagues' study4 and the absence of evidence for risk with these drugs, recommendations on the use of glucose-lowering drugs by people with type 2 diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic might now become more liberal, allowing use of all glucose-lowering drugs in stable situations. However, because of the limitations of such real-world studies, prospective randomised clinical trials are necessary to more meaningfully explore which glucose-lowering agents, if any, induce benefit or harm in patients with COVID-19. Irrespective of therapy choice, strict management of cardiovascular risk factors and tight glycaemic control are crucial for patients with diabetes and COVID-19. Antithrombotic therapy for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19-associated thrombosis3 as well as anti-inflammatory therapy10 will hopefully translate into improved outcomes.3 Finally, vaccination prioritisation of patients with type 2 diabetes who are at very high risk of severe COVID-19 could help protect this vulnerable population.

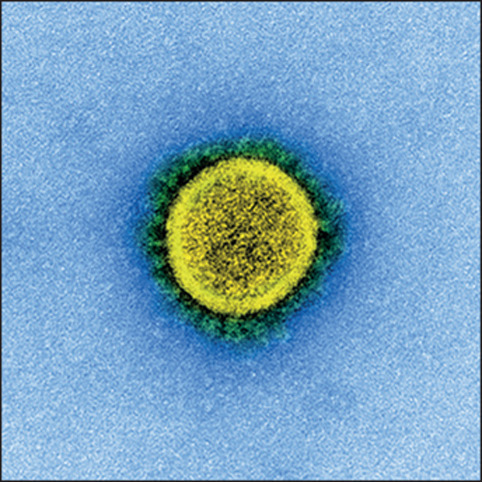

© 2021 NIAID/NIH/Science Photo Library

I have received personal fees for lectures and advisory board memberships from Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Mundipharma, AstraZeneca, and Takeda.

References

- 1.Barron E, Bakhai C, Kar P, et al. Associations of type 1 and type 2 diabetes with COVID-19-related mortality in England: a whole-population study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8:813–822. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30272-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bornstein SR, Dalan R, Hopkins D, Mingrone G, Boehm BO. Endocrine and metabolic link to coronavirus infection. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16:297–298. doi: 10.1038/s41574-020-0353-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McFadyen JD, Stevens H, Peter K. The emerging threat of (micro)thrombosis in COVID-19 and its therapeutic implications. Circ Res. 2020;127:571–587. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khunti K, Knighton P, Zaccardi F, et al. Prescription of glucose-lowering therapies and risk of COVID-19 mortality in people with type 2 diabetes: a nationwide observational study in England. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021 doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(21)00050-4. published online March 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wargny M, Potier L, Gourdy P, et al. Predictors of hospital discharge and mortality in patients with diabetes and COVID-19: updated results from the nationwide CORONADO study. Diabetologia. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s00125-020-05351-w. published online Feb 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kow CS, Hasan SS. Mortality risk with preadmission metformin use in patients with COVID-19 and diabetes: a meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2021;93:695–697. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Israelsen SB, Pottegård A, Sandholdt H, Madsbad S, Thomsen RW, Benfield T. Comparable COVID-19 outcomes with current use of GLP-1 receptor agonists, DPP-4 inhibitors or SGLT-2 inhibitors among patients with diabetes who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2021 doi: 10.1111/dom.14329. published online Jan 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lim S, Bae JH, Kwon H-S, Nauck MA. COVID-19 and diabetes mellitus: from pathophysiology to clinical management. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2021;17:11–30. doi: 10.1038/s41574-020-00435-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schernthaner G, Shehadeh N, Ametov AS, et al. Worldwide inertia to the use of cardiorenal protective glucose-lowering drugs (SGLT2i and GLP-1 RA) in high-risk patients with type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2020;19:185. doi: 10.1186/s12933-020-01154-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.RECOVERY Collaborative Group Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:693–704. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]