The COVID-19 pandemic has raised challenging questions about the rationing of intensive care unit (ICU) beds, mechanical ventilators, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO).1 Experts have recommended that ECMO be curtailed or even halted when patient numbers surpass an ill defined threshold, wherein demand for critical care outstrips available resources.2 It might seem counterintuitive to reduce the provision of ECMO at precisely the time when demand increases, yet it could be deemed necessary. In this Comment, we argue that a decision to curtail or continue ECMO should be deliberate and reasoned, such that alternatives are actively rejected.

According to a large German registry, approximately 17% of patients with COVID-19 treated in hospital during the first few months of the pandemic required mechanical ventilation and 1% received ECMO.3 Both modalities are complex and can entail a prolonged ICU stay; however, the resource intensity of ECMO is typically higher, especially with respect to ICU staffing.4 Therefore, if ICU staff are the primary scarce resource, cessation of an ECMO programme might result in more patients being treated. However, if it is not staff that are scarce, but mechanical ventilators or ICU beds, the same might not hold true.

ECMO comes relatively late in the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) treatment algorithm, and is only considered in a subset of patients with the most severe forms of ARDS.5 The value of ECMO is not universally accepted as part of established critical care in the way that mechanical ventilation is; therefore, access to ECMO might not be regarded as a right equal to access to mechanical ventilation.

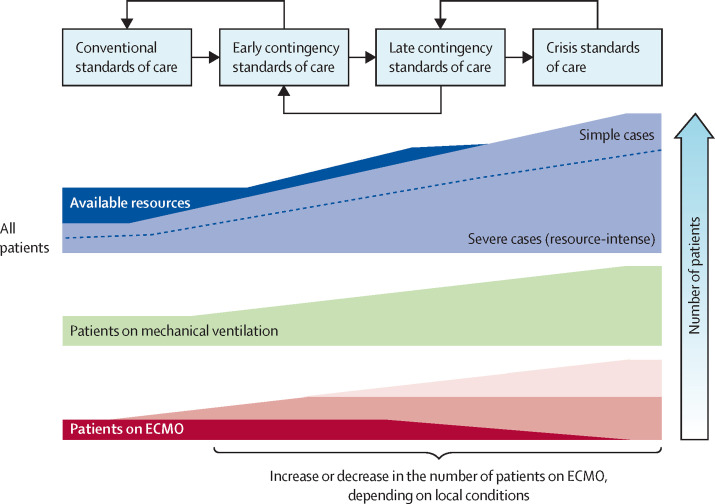

When the volume of patients increases and demand surpasses available resources, hospitals and health systems seriously affected by the COVID-19 pandemic or other crises must transition from conventional standards of care to contingency standards and, ultimately, to crisis standards of care, if mitigation efforts are not sufficiently successful (figure ; appendix pp 1–2).6 It is particularly challenging to identify the specific point in time during a pandemic when crisis standards of care should be adopted. Unlike a single mass casualty event, the experience with COVID-19 suggests that the process will be dynamic during a pandemic, with a threshold that is crossed more than once in both directions, and that different resources will be constrained at different points in time.7 Furthermore, it has been clear that many governmental agencies will be reluctant to invoke crisis standards of care for political reasons, even when potentially lifesaving treatments, which under normal conditions are available in sufficient quantities to everyone who needs them, become scarce and must be rationed at individual hospitals to a much greater degree than under normal circumstances.8

Figure.

Transitioning between standards of care during an acute crisis

Before life-saving treatments are rationed, efforts should be taken to extend available resources and to use them most efficiently and effectively. These efforts have to be continued, even after entering crisis standards of care, to return to a previous step as soon as possible. Depending on the ethical principles adopted and patient characteristics, levels of ECMO offered could be the same as those provided during normal circumstances, reduced, or even increased during the transition from normal to crisis standards of care. ECMO=extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Two basic elements should be considered for decision making and balancing of resources between treatment with mechanical ventilation and ECMO: consensus on the prioritisation of ethical principles, including outcome-oriented utilitarian principles and rights-oriented egalitarian principles, as the basis for rationing decisions, and incorporation of these principles into triage guidelines for use during crises.1, 7 Ideally, this prioritisation exercise should occur before a crisis occurs. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, such consensus had not been achieved in time to act. In this situation, experts, professional organisations, and governments must attempt to reach agreement on the principles to be applied to guide bedside clinicians who have no choice but to make such decisions, with or without the guidance of society at large.

Calls for a limitation of ECMO services under late contingency or crisis standards of care are aimed at assuring that the highest number of patients can be treated with mechanical ventilation or other ICU resources.2 Before assuming that rationing of ECMO is the optimal approach, the validity of the argument and the underlying principles should be disclosed and discussed, and the alternatives explicitly rejected.

When rationing is required, a standard therapeutic measure such as ECMO should not be reduced or withheld simply because it is resource intense. Such a decision must follow individual patient-centred considerations. If utilitarian reasoning is adopted as a guiding principle, outcome prediction with suitable and validated scores should be applied. Precise scores of this nature do not exist at present.9 Limited resources should then be distributed in a way that allows health systems to achieve the highest number of lives saved. This approach could result in reduced, unchanged, or even increased numbers of patients being treated with ECMO, depending on the specific resources in scarcity and the purported effectiveness of ECMO use in the patients in question. If an approach more focused on individual rights is favoured instead, emphasis will be on guaranteeing a fair process for the distribution of scarce resources. Again, although this choice might result in reducing the number of patients treated with ECMO, there are circumstances in which this will not be the case.

Under crisis standards of care, with an overwhelming number of patients competing for a scarce resource (eg, mechanical ventilation or ECMO), a thorough comparative assessment of individual risks and prognosis will be challenging. Therefore, final allocation decisions and commitment to the degree to which ECMO services can be provided require careful assessment of the specific resources that are scarce, the (additional) resources required for ECMO at a given centre, and the effect on other patients of choosing to offer ECMO to a specific patient in this environment. Further changes in ECMO technology, the human resources needed, or the evidence base supporting ECMO could alter the balance of whether or not to provide ECMO during late contingency or crisis standards of care during a pandemic.

Offering ECMO to a patient during a crisis also depends on the capabilities of the individual centre, including the actual effectiveness of this intervention at the respective centre under the current circumstances. Effectiveness of critical care can decrease when systems are under stress.10 If a centre has had no survivors among their patients treated with ECMO during a crisis, this should be factored into decision making. However, if many patients are believed to have survived because of ECMO, this should prompt greater consideration of the intervention, even in the context of waning resource availability.

There is neither an ethical nor an operational imperative requiring the cessation of ECMO services during a public health crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Ethical principles and triage guidelines based on these principles might or might not result in the cessation of ECMO services when demand outstrips available resources, depending on the circumstances and the choices made. Importantly, we believe that cessation of ECMO is an ethical option that should be explicitly considered during late contingency and crisis standards of care.

Acknowledgments

AS reports research grants and lecture fees from CytoSorbents and lecture fees from Abiomed, outside of the submitted work. DB reports grants from ALung Technologies; personal fees from Baxter, Xenios, and Abiomed; and unpaid consultancy for Hemovent, outside of the submitted work. JRC reports grants from the National Institutes of Health and the National Palliative Care Research Center, and grants and personal fees from Cambia Health Foundation, outside of the submitted work. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Emanuel EJ, Persad G, Upshur R, et al. Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2049–2055. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb2005114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abrams D, Lorusso R, Vincent JL, Brodie D. ECMO during the COVID-19 pandemic: when is it unjustified? Crit Care. 2020;24:507. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03230-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karagiannidis C, Mostert C, Hentschker C, et al. Case characteristics, resource use, and outcomes of 10 021 patients with COVID-19 admitted to 920 German hospitals: an observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:853–862. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30316-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peek GJ, Elbourne D, Mugford M, et al. Randomised controlled trial and parallel economic evaluation of conventional ventilatory support versus extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe adult respiratory failure (CESAR) Health Technol Assess. 2010;14:1–46. doi: 10.3310/hta14350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abrams D, Ferguson ND, Brochard L, et al. ECMO for ARDS: from salvage to standard of care? Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7:108–110. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30506-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hick JL, Christian MD, Sprung CL. European Society of Intensive Care Medicine's Task Force for intensive care unit triage during an influenza epidemic or mass disaster. Chapter 2. Surge capacity and infrastructure considerations for mass critical care. Recommendations and standard operating procedures for intensive care unit and hospital preparations for an influenza epidemic or mass disaster. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36(suppl 1):S11–S20. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-1761-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Supady A, Curtis JR, Abrams D, et al. Allocating scarce intensive care resources during the COVID-19 pandemic: practical challenges to theoretical frameworks. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9:430–434. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30580-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gutmann Koch V, Han SA. COVID in NYC: What New York did, and should have done. Am J Bioeth. 2020;20:153–155. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2020.1777350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wynants L, Van Calster B, Collins GS, et al. Prediction models for diagnosis and prognosis of covid-19 infection: systematic review and critical appraisal. BMJ. 2020;369 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asch DA, Sheils NE, Islam MN, et al. Variation in US hospital mortality rates for patients admitted with COVID-19 during the first 6 months of the pandemic. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.8193. https://doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.8193 published online Dec 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.