Abstract

Chronic Azithromycin is a common treatment for lung infection. Among adults at risk of cardiac events, AZM use has been associated with cardiovascular harm. We assessed cardiovascular safety of AZM among children with CF, as a secondary analysis of a placebo-controlled, clinical trial, in which study drug was taken thrice-weekly for a planned 18 months. Safety assessments using electrocardiogram (ECG) occurred at study enrollment, and then after 3 weeks and 18 months of participation. Among 221 study participants with a median of 18 months follow-up, increased corrected QT interval (QTc) of ≥ 30 msec was rare, at 3.4 occurrences per 100 person-years; and incidence of QTc prolongation was no higher in the AZM arm than the placebo arm (1.8 versus 5.4 per 100 person-years). No persons experienced QTc intervals above 500 msec. Long-term chronic AZM use was not associated with increased QT prolongation.

Keywords: cystic fibrosis, azithromycin, pulmonary exacerbation, QT prolongation

Introduction

Over the past 2 decades, there has been evidence that azithromycin administration may be associated with increased cardiovascular (CV) risk in adults particularly with underlying CV conditions. Following several case reports [1], a large observational study among adult Tennessee Medicaid subscribers in 2013 reported that death from CV causes was 2.9 times as high among persons who used azithromycin (AZM) in the last 5 days, after controlling for confounding using propensity scores [2]. The US FDA issued a Drug Safety Communication urging prescribing clinicians to consider the small increased risk of CV harm, including QTc interval prolongation, for those who are already at risk [3]. At that time, there was no evidence regarding the impact of macrolide use on the QTc in children.

The OPTIMIZE trial (Optimizing Treatment for Early Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infection in Cystic Fibrosis) was a randomized, double-blinded, multicenter trial comparing thrice-weekly AZM to placebo, both provided in addition to standardized tobramycin inhalation solution. The study was conducted between June 2014 and March 2017, and assessed incidence of pulmonary exacerbation as a primary outcome in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis (CF) [4]. Children aged 6 months to 18 years of age with early P. aeruginosa infection were eligible. The study design and findings have been reported elsewhere [4]. Relevant to this report, ECGs were assessed at baseline, 3 weeks, and 18 months.

The main OPTIMIZE findings were reported in 2018 [4]. In total, 221 children aged 6 to 18 years participated in the trial with 110 randomized to AZM and 111 to placebo. The randomized study ended after an interim analysis, by recommendation of the NHLBI DSMB; and participants were subsequently unblinded and permitted to take physician-prescribed AZM regardless of randomization. During the randomized portion of the study, study drug was temporarily stopped when QT-prolonging medications (besides AZM) were deemed medically necessary. We briefly noted in the primary study paper that QTc prolongation was rare in the randomized portion of the study [4]. Here we report on CV safety, as measured by ECG, over all follow-up visits including the subsequent open-label phase of this trial.

Methods

Standard 12-lead ECGs were obtained using MAC-PC or MAC-12 digital ECG systems (GE-Marquette Medical Systems, Inc., Milwaukee, Wisconsin). Ten seconds of data were digitally recorded at 250 Hz at 5μV resolution and was stored in a Marquette MUSE system with automated computerized measurements of waveforms. QTc was computed using Bazett’s correction for heart rate as QT divided by the square root of the preceding RR interval (QTc=QT/RR1/2) [5, 6]. We defined a baseline abnormality as QTc > 460 msec, and any incident abnormalities as either QTc > 500 at subsequent visits, or as a prolongation (increase) in QTc of at least 30 msec relative to any previous visit. QTc prolongations identified at a study site were subjected to confirmation by a real-time over reader. In such occurrences, paper copies of available ECGs from all study visits were re-read together by a single pediatric cardiologist to determine if QTc prolongation of ≥30 msec occurred, using a standard approach to correction: averaging 3 pairings of QT and RR intervals from a single ECG [5]. Only QTc prolongations confirmed as abnormal by the over reader are included in analyses. Participants with confirmed abnormal ECG findings prior to the last study visit were instructed to stop study drug early. Linear mixed models with random term for each individual were used to assess whether average values of QTc changed over the course of the study. Treatment taken was used rather than arm of randomization, since many participants continued into the open-label period and began taking AZM.

Results

Demographics of OPTIMIZE study participants has been provided elsewhere, but briefly, the average age was 7 years, 47% were female, 88% were white, and they had an average baseline percent predicted forced expiratory volume (ppFEV1) of 94%. Of the 221 randomized, 167 (76%) completed a month 18 visit with ECG (Table 1). Participants accrued 292 person-years of time over all study participation; median follow-up was 18 months (5th to 95th percentiles: 5 to 19 months). One-hundred twelve persons contributed 90 person-years of accrued time during the open-label phase; median amount of time contributed during the open-label phase was 1.5 months (5th to 95th percentiles: 0 to 16 months).

Table 1. QT interval length by treatment taken and overall, for each visit.

Note that treatment taken at later visits (the open-label phase) may not match randomized study drug. For example, the 115 study participants who provided an ECG while taking azithromycin at the month 18 visit include persons who were initially randomized to placebo.

| Mean (standard deviation), n | Treatment taken | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| All | Placebo | Azithromycin | |

| Baseline visit | 411 (26), 221 | 407 (30), 111 | 416 (20), 110 |

| Week 3 visit | 413 (23), 215 | 411 (26), 106 | 415 (21), 109 |

| Month 18 visit | 413 (25), 167 | 410 (27), 52 | 414 (23), 115 |

| Early exit | 422 (20), 25 | 423 (22), 13 | 421 (18), 12 |

Longitudinal assessments of QTc interval changes

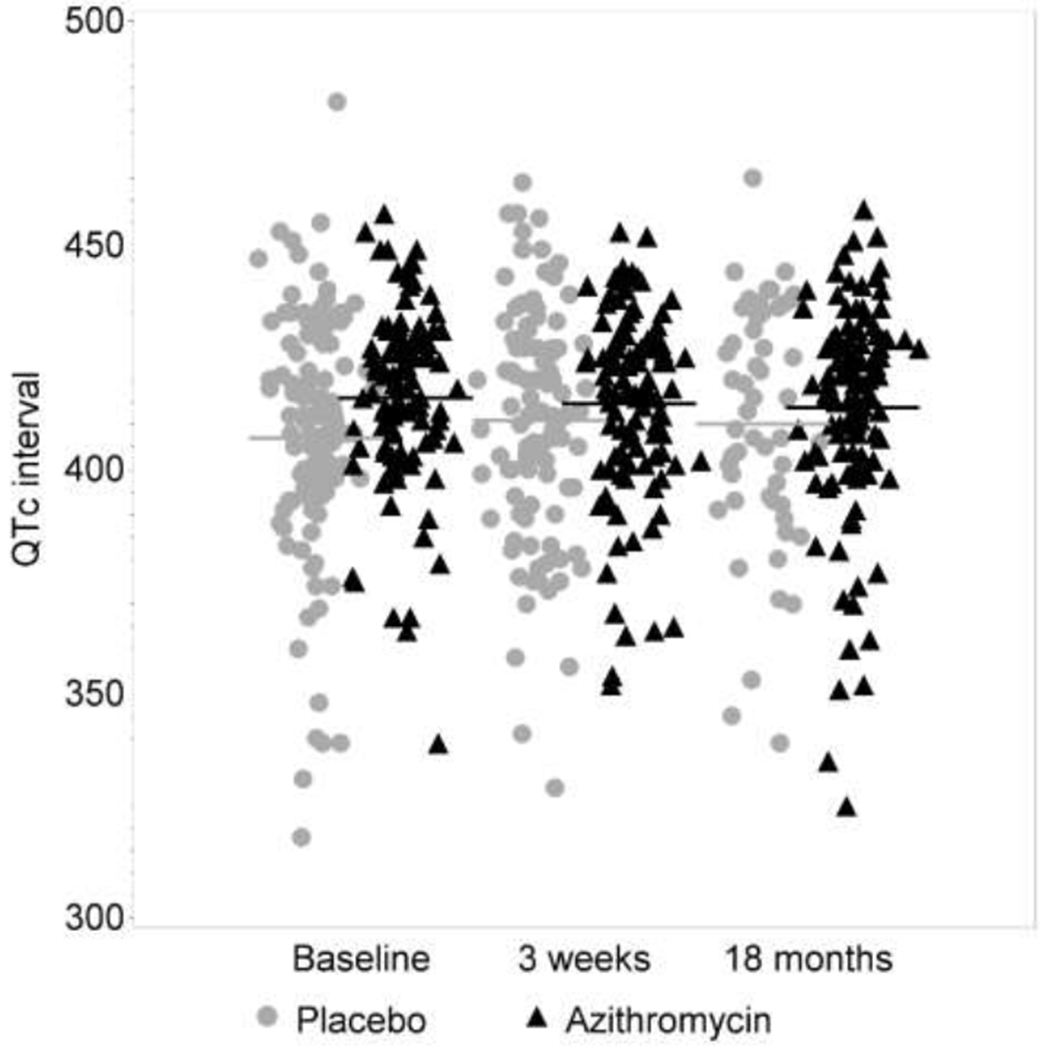

Among the 221 study participants, 628 ECGs were obtained. Average and individual-level QTc durations are shown over time, by treatment group (Table 1 and Figure 1). In regression, we did not find evidence that the QTc interval increased relative to baseline either at the week 3 (+0.7 msec, p=0.63) or the month 18 visits (+0.6 msec, p=0.71). We also found no evidence that estimated changes over time differed by treatment group (p-value for interaction of time with treatment of p=0.16 and p=0.40 at the week 3 and month 18 visits, respectively).

Figure 1. QTc over time and by treatment taken.

Lines show group-specific means by treatment taken at each visit. Because of the open-label drug phase, more participants are taking AZM during the later visits.

QTc prolongation

No persons at any time over either the randomized phase or the open-label phase experienced a QTc interval greater than 500 msec. Confirmed QTc prolongations, defined as increases of ≥30 msec relative to previous visit(s), occurred in 10 study participants. Seven placebo recipients and 1 participant on AZM had a confirmed QTc prolongation during the randomization phase [4], and 2 additional prolongations occurred while receiving AZM during the open-label phase (Table 2). The overall incidence of QTc prolongation was 3.4 QTc rises per 100 person-years (95% CI 1.7 to 5.7). Computed separately by treatment taken, we observed 3 QTc prolongations over 163 person-years contributed while taking AZM (1.8 per 100 person-years, 95% CI 0.4 to 4.1) and 7 over 130 person-years on placebo (5.4 per 100 person-years, 95% CI 2.8 to 7.9). We did not find evidence that AZM increased QTc interval versus placebo.

Table 2. Individual characteristics among those with a confirmed QTc interval increase (10 persons).

Values used to compute the rise are shown in bold in the table below. Only 3 of the 10 abnormalities occurred while taking Azithromycin.

| Time rise noted | Age (years) | Treatment taken | Study drug discontinued | QTc by real-time over reader | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Week 3 | 18 mo. | Exit | ||||

| Week 3 visit | 1.1 | Placebo | Y | 380 | 420 | . | |

| Week 3 visit | 1.1 | Placebo | Y | 398 | 426* | . | |

| Week 3 visit | 6.7 | Placebo | Y | 412 | 455 | 456 | |

| Week 3 visit | 13.1 | Placebo | Y | 394 | 434 | . | |

| Month 18 visit | 4.4 | Azithromycin | N | 428 | 390 | 433 | |

| Month 18 visit | 8.8 | Placebo | N | 411 | 389 | 438 | |

| Month 18 visit | 10.6 | Placebo | N | 383 | 438δ | 450 | |

| Month 18 visit | 15.8 | AzithromycinΨ | N | 381 | 383 | 413 | |

| Month 18 visit | 16.0 | Azithromycin | N | 392 | . | 423 | |

| Early exit | 2.4 | Placebo | N | 401 | 370 | 415 | |

This rise was only 28 msec, but over reader considered it important and stopped drug.

The site-measured rise between baseline and week 3 was 29 msec, and those values were not sent to over reader until the month 18 visit.

This participant was randomized to placebo, but had been taking chronic AZM for 8 months during the open label phase when the abnormality occurred. All other treatments taken match the study drug arm assigned at randomization.

Concurrent medications

Thirty-five of participants (16%) had study drug temporarily discontinued in order to treat with a QT-prolonging, prohibited antibiotic. Thirty-seven participants (17%) took modulators (mostly ivacaftor and lumacaftor/ivacaftor) over a median of 13 months, with 25 of those participants also concurrently taking AZM.

Discussion

The safety of AZM is of interest since chronic macrolide therapy is one of the most common therapies used in people with CF [7]. The OPTIMIZE Trial, the longest randomized, placebo-controlled trial in a pediatric population with CF, provides important reassurance against any sizable risk of QTc prolongation from chronic AZM use. Previous evidence of CV safety comes from an early pediatric trial lasting less than 6 months [8]. Recent observational studies involving children taking AZM also support the safety of AZM over shorter treatment durations [9, 10].

Limitations of our study include the reliance upon measures of QTc interval known to be sensitive to variability in heart rate. However among children, Bazett’s approach, or a very similar function QTc = QT/RR0.41, are preferred to other standard methods as they has been shown to be least dependent on heart rate [11, 12].

Few of our participants took other, concurrent, QT-prolonging drugs, and few were taking modulators. Future research will be needed to understand if and how macrolides impact on the increasingly healthy CF population, many of whom are now benefitting from highly effective CFTR modulator drugs [13, 14]. Reducing the burden and cost of therapy is a shared goal among patients and providers, and so it is important to determine if any longstanding therapy, including AZM, continues to provide benefit.

Highlights.

Long-term trial of chronic azithromycin in children with CF and P. aeruginosa

Cardiovascular health was measured using electrocardiogram

Thrice weekly azithromycin for up to 18 months was found to be safe

Incidence of QT prolongation was not higher among those taking azithromycin

Acknowledgments

Funding sources:

NIH grants U01HL114623 and U01HL114589 as well as UL1TR0002319.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Shaffer D, et al. , Concomitant risk factors in reports of torsades de pointes associated with macrolide use: review of the United States Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System. Clin Infect Dis, 2002. 35(2): p. 197–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ray WA, et al. , Azithromycin and the risk of cardiovascular death. N Engl J Med, 2012. 366(20): p. 1881–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Food and Drug Administration, FDA Drug Safety Communication: Azithromycin (Zithromax or Zmax) and the risk of potentially fatal heart rhythms. 2013: https://www.fda.gov/media/85787/download. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mayer-Hamblett N, et al. , Azithromycin for Early Pseudomonas Infection in Cystic Fibrosis. The OPTIMIZE Randomized Trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2018.198(9): p. 1177–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldenberg I, Moss AJ, and Zareba W, QT interval: How to measure it and what is “normal”. Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology, 2006. 17(3): p. 333–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Postema PG, et al. , Accurate electrocardiographic assessment of the QT interval: Teach the tangent. Heart Rhythm, 2008. 5(7): p. 1015–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. 2018 Patient Registry Annual Report. 2018; Available from: https://www.cff.org/Research/Researcher-Resources/Patient-Registry/2018-Patient-Registry-Annual-Data-Report.pdf.

- 8.Saiman L, et al. , Azithromycin in patients with cystic fibrosis chronically infected with Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 2003. 290(13): p. 1749–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valdes SO, et al. , Cardiac Arrest in Pediatric Patients Receiving Azithromycin. J Pediatr, 2017. 182: p. 311–314 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Espadas D, et al. , Lack of effect of azithromycin on QT interval in children: a cohort study. Arch Dis Child, 2016.101(11): p. 1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phan DQ, et al. , Comparison of Formulas for Calculation of the Corrected QT Interval in Infants and Young Children. Journal of Pediatrics, 2015. 166(4): p. 960–U271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benatar A and Feenstra A, QT Correction Methods in Infants and Children: Effects of Age and Gender. Annals of Noninvasive Electrocardiology, 2015. 20(2): p. 119–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heijerman HGM, McKone EF, and Downey DG, Efficacy and safety of the elexacaftor plus tezacaftor plus ivacaftor combination regimen in people with cystic fibrosis homozygous for the F508del mutation: a double-blind, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet, 2019. 394: p. 1940–1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Middleton PG, Mall MA, and Drevinek P, Elexacaftor-Tezacaftor-lvacaftorfor Cystic Fibrosis with a Single Phe508del Allele. New England Journal of Medicine, 2019. 381(19): p. 1809–1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]