Abstract

Delirium in the intensive care unit (ICU) affects up to 80% of critically ill, mechanically ventilated (MV) adults. Delirium is associated with substantial negative outcomes, including increased hospital complications and long-term effects on cognition and health status in ICU survivors. The purpose of this randomized controlled trial is to test the effectiveness of a Family Automated Voice Reorientation (FAVoR) intervention on delirium among critically ill MV patients. The FAVoR intervention uses scripted audio messages, which are recorded by the patient’s family and played at hourly intervals during daytime hours. This ongoing orientation to the ICU environment through recorded messages in a voice familiar to the patient may enable the patient to more accurately interpret the environment and thus reduce risk of delirium. The study’s primary aim is to test the effect of the FAVoR intervention on delirium in critically ill MV adults in the ICU. The secondary aims are to explore: (1) if the effect of FAVoR on delirium is mediated by sleep, (2) if selected biobehavioral factors moderate the effects of FAVoR on delirium, and (3) the effects of FAVoR on short-term and long-term outcomes, including cognition and health status. Subjects (n = 178) are randomly assigned to the intervention or control group within 48 hours of initial ICU admission and intubation. The intervention group receives FAVoR over a 5-day period, while the control group receives usual care. Delirium-free days, sleep and activity, cognition, patient-reported health status and sleep quality, and data regarding iatrogenic/environmental and biobehavioral factors are collected.

Introduction

Delirium is associated with negative outcomes, including longer duration of MV, greater incidence of complications, and long-term effects on cognition in intensive care unit (ICU) survivors. Delirium occurs in up to 80% of mechanically ventilated (MV) ICU patients, and experience at a higher rate for cognitive dysfunction. Patients with delirium have longer durations of MV, greater incidence of complications, and higher hospital mortality than patients without delirium [1]. Number of days of delirium is an independent predictor of mortality in ICU patients [2–4]. Sleep deprivation is common among ICU patients, is associated with risk of delirium [5–7], and may also interact with interventions aimed at reducing delirium. ICU delirium is associated with lasting sequelae [8–11]. Data suggest that 25–78% of patients with delirium in the ICU suffer significant post-ICU cognitive dysfunction [12–14]. Cognitive dysfunction may persist for months or become permanent [10, 12, 15]. Reducing delirium in MV ICU patients may reduce both short- and long-term cognitive dysfunction.

Because of the extensive incidence and negative outcomes associated with delirium, identification of effective interventions to reduce delirium is important. To date, the focus of delirium research has been on detection of existing delirium and its pharmacologic treatment [16]. Few studies have focused on delirium prevention using non-pharmacological interventions. Providing orientation to MV patients, especially messages recorded by family, could be an innovative and effective way to provide reorientation to MV ICU patients. Small studies have evaluated the effects of family-recorded messages on comatose patients with head injuries [17, 18]. In a small RCT (n = 40) of comatose patients with acute subdural hematoma, patients who received recorded family messages of encouragement twice a day for 10 days had better GCS scores on day 10 compared with control patients [19]. However, the use of a recorded family voice to improve orientation and reduce delirium has not been tested in a large and rigorously designed clinical trial among MV ICU patients. Thus, we developed a cognitive reorientation intervention using scripted audio messages, recorded by the patient’s family and played at hourly intervals during daytime hours, to provide information about the ICU environment (Family Automated Voice Reorientation intervention: FAVoR).

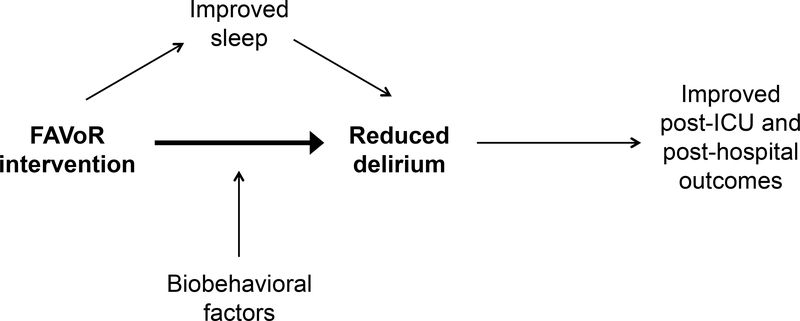

Using a randomized controlled trial design, subjects (n = 178) are randomly assigned to 1) the FAVoR intervention group, or the 2) control group. The primary aim of the proposed project is to test the effect of the FAVoR intervention on delirium in MV ICU adults. We hypothesize that subjects who receive the FAVoR intervention will have less delirium than control subjects who do not receive the intervention. The secondary aims of this project are to: (1) explore if the effect of FAVoR on delirium is mediated by sleep, (2) explore if selected biobehavioral factors may potentially moderate the effects of FAVoR on delirium, and (3) examine the effects of FAVoR on short-term (immediately after ICU discharge) and long-term (1 and 6 months after hospital discharge) outcomes, including cognitive function and patient-reported health status. A study model is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized Relationships between FAVoR Study Variables

Methods

Design.

A prospective, randomized, experimental design is used to accomplish the specific aims. Subjects (n = 178) are randomly assigned, within 48 hours of initial intubation and ICU admission, to one of two groups. The intervention group receives the FAVoR intervention over a 5-day period (120 hours) or until discharge from the ICU, if discharged within 5 days. The control group receives standard ICU care without the FAVoR intervention. All subjects receive standard clinical care for MV patients. Institutional Review Board (IRB) approvals were obtained prior to initiation of the trial. Written informed consent in English or Spanish is obtained from all subjects’ legally authorized representatives (LAR).

Sample and Setting.

Because delirium occurs with a greater frequency in those who are mechanically ventilated [20], this study focuses on subjects who are mechanically ventilated. The sample of 178 subjects are screened and recruited from all 9 ICUs at two large hospitals in South Florida. Inclusion criteria are as follows: 1) patients ages 18 and older; 2) within 48 hours of initial ICU admission and intubation at time of enrollment; 3) they or their legally authorized representative (LAR, ages 18 and older) must be able to provide informed consent in English or Spanish; and 4) a family member able to speak English or Spanish must be available and willing to audio record scripted messages. Exclusion criteria include 1) dementia; 2) anticipation by the clinical provider of imminent patient death and medical contraindication to the intervention, or 3) inability to speak either English or Spanish.

Statistical Power and Sample Size Justification.

In our previous study, we planned for an attrition rate of 40% to account for early extubation and death related to critical illness, but attrition was less than 30%. The recently completed BRAIN-ICU descriptive study of ICU survivors reported a 43% attrition from the inpatient time points to the 12 month follow up time point [15]. While early extubation will not affect attrition in this study, given that a secondary aim of the proposed project plans 1 and 6 month post-hospital discharge follow up, we conservatively planned for a 40% attrition rate. We plan to use the Chi-square test to compare the proportions of delirium-free days in two groups, at the baseline and the end of ICU intervention. For our power calculation, we used data from our preliminary study [21]. Using the pilot data and PASS software (http://www.ncss.com/software/pass/), we computed the effect size (W) for the contingency table analysis to be W = 0.35. Then we computed the sample sizes to detect an effect size of W = 0.35 for a statistical power of 0.8, 0.9 and 0.95 using the PASS software. A sample size of 79, 104, and 127 achieves 80%, 90%, and 95% power respectively to detect an effect size of 0.35 using a 2 degrees of freedom Chi-Square Test with a significance level (alpha) of 0.05; we plan for 95% power. After adjusting the analysis sample size of 127 by an anticipated 40% attrition rate, the planned recruitment sample size is 178 total (89 in each group).

Recruitment and Enrollment.

We obtained a partial HIPAA waiver from our institutional IRB to electronically screen potentially eligible ICU patients who are mechanically ventilated. We follow an inclusion/exclusion criteria checklist to identify potentially eligible subjects via the electronic medical record. If the patient meets this initial set of enrollment criteria, then research personnel approach the patient’s bedside nurse to ask for pertinent additional information about the patient. Once the family member/LAR is identified, then research personnel approach the family member for consent by proxy. If the family member/LAR is not available at bedside to sign informed consent, we obtained permission from our IRB to contact the LAR via phone call, to set up a time/place to obtain informed consent face-to-face and audio record messages.

Randomization.

Subjects are randomly assigned to one of two study groups (FAVoR intervention or control) using randomization processes, which subjects are randomized to either group according to a permuted block design. This permuted block design was created such that after every k subjects, balance is maintained between the groups [22]. The random assignments are placed into sealed opaque envelopes. Research personnel completing the CAM-ICU assessments are blinded to group assignments. Subjects in both groups are reoriented by care providers as part of usual care practices.

Intervention Group (FAVoR intervention): Subjects in the intervention group receive personalized digitally recorded reorientation messages administered for up to 2 minutes every hour over an 8-hour daytime period (beginning at 9 am daily) recorded in the voice of a family member. Subjects in the intervention group continue to receive the intervention for up to a total of 5 days (120 hours), or until ICU discharge if ICU discharge occurs within the first 5 days.

Control Group: The control group consists of usual care and does not receive audio reorientation messages. Subjects remain in the study for 5 days or until ICU discharge if discharged before 5 days.

Description of Intervention.

The FAVoR intervention includes a set of 10 recorded sentences in English or Spanish, which were developed, tested, and refined in our pilot study; the English script has been published [21]. Each message is scripted, is no longer than 2 minutes long, uses simple terms, and is written at a 5th grade reading level. Messages include information about the ICU environment, the general visual and auditory stimuli that may be expected, and the availability of healthcare providers and family members. The messages call the patient by name (preferred name as recommended by the patient’s family); we believe the use of the patient’s name may create greater attention to the message.

Each message indicates that it is daytime, states that the message is a recorded message, and tells the subject that he/she hears messages frequently throughout the day to help him/her understand that he/she is in the ICU. Other than the patient’s name, the recorded message is generic in nature, and not specific to any one patient’s admission diagnoses or conditions, procedures, or family situations. Topics for message scripts were developed in response to patients’ recollections of the ICU experience [23–25]. The timeframe chosen for intervention delivery coincides with usual waking hours (9:00 AM - 4:00 PM); no messages are played outside of this timeframe, so as not to disturb sleep in the evening hours and provide day/night orientation. Further, early morning hours are typically times of patient care intensity, so additional stimulation before 9:00 AM may not be appropriate. Based on our preliminary studies, we found that by placing the speaker near the patient’s ear, the recorded message is able to be heard at a volume that is loud enough for the patient, but not so loud as to be noxious or interfere with care-related activities.

The messages are recorded by a family member of the family’s choice using our standardized script [21], in either English or Spanish, based on the family member’s decision regarding which language would be most meaningful to the subject. Family members are not human subjects in this project; no data are collected about the family members. The messages are digitally recorded using audio software (Audacity) and stored as standard Microsoft MP3 files. The MP3 files are loaded onto a wireless speaker, placed near the subject’s ear, and set to continuous play. Each track includes the 2-minute recorded message, followed by 58 minutes of generated silence, which enables each track to automatically play the recorded message hourly. The tracks vary randomly in order at each hourly interval, reducing message repetition, which may eventually annoy or be ignored by the subject. All intervention “doses” are administered between the hours of 9:00 AM and 4:00 PM for each of the 5 ICU days (or until ICU discharge if ICU discharge occurs prior to 5 days), with the intervention beginning at the earliest available time following completion of family audio recording. The research personnel document the time and number of recorded tracks played each day, so that the number of message “doses” can be documented. Research personnel monitor the subject and the recorded messages regularly to document if the subject was not in the unit (e.g., off the unit for a procedure, etc.), so that those off-unit times can be included in the dose calculation. Research staff will turn off the recorded message if a 20% or larger fluctuation in vital signs (heart rate and blood pressure) during the recorded message occurs.

Key Variables and Measurement

Delirium.

The primary outcome measure for this project is delirium-free days. We quantify delirium using the Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU 7 (CAM-ICU 7) [26, 27]. CAM-ICU scores for each subject are obtained by research personnel twice daily at approximately 8:45 AM and 4:15 PM (coinciding with the schedule for initiation and conclusion of messages each day in the FAVoR intervention group, and at identical times for the control group). CAM-ICU assessments are conducted at the same times for two additional days following the completion of the intervention period, for a total of 7 days of CAM-ICU assessments, or until ICU discharge if ICU discharge occurs within 7 days. Each CAM-ICU assessment is completed by research personnel who are blinded to the subject’s group assignment.

In addition to the CAM-ICU assessments, we review episodes of delirium via documentation by providers through electronic medical records during the 7-day assessment period across both groups. Only days without any instances of delirium are counted as delirium-free days. The CAM-ICU is recognized in the Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Pain, Agitation, and Delirium in Adult Patients [28] in ICU as a valid, reliable, and feasible tool to detect delirium in ICU patients [29] with pooled sensitivity of 75.5% and specificity of 95.8% [27, 30].

Sleep/Activity.

We use the FDA-approved Sleep Profiler system (Advanced Brain Monitoring, Carlsbad, CA) to obtain continuous polysomnography data [31, 32]. The Sleep Profiler (SP-PSG) has been successfully utilized in mechanically ventilated and sedated patients and provides three frontopolar signals: electroencephalographic (EEG) signal (AF7/AF8), and left and right electrooculargraphic (EOG) signals (AF7/Fpz and AF8/Fpz) [33]. Additionally, a wrist actigraph (Actiwatch Spectrum, Philips Respironics, Bend, OR) is placed on the wrist to measure patient activity and ambient light levels. Wrist actigraphy has been found to be a reliable method of assessing sleep and activity in the ICU [34, 35].

Iatrogenic/Environmental Factors.

Critical illness and its treatment predispose patients to delirium through several mechanisms which are poorly understood. Iatrogenic/environmental factors (ambient light and pharmacological therapies) are collected, discussed below.

Ambient Light.

Although the FAVoR intervention does not involve manipulation of ambient light levels, environmental conditions have been hypothesized to influence risk of delirium and may affect sleep in the ICU. Wrist actigraphy described above, is able to capture light data in the ICU during the 5-day study period.

Pharmacological Therapies Affecting Cognition and Sleep.

We collect data regarding specific pharmacologic therapies. For sedatives and narcotics, we calculate equivalent doses to facilitate analysis. To provide sedative and analgesic dose equivalents for analysis, doses are converted as described in this study [36].

Biobehavioral Factors: Disease Severity and Comorbid Conditions.

Biobehavioral factors predispose patients to delirium through several mechanisms which are poorly understood. Factors including patient demographic characteristics, severity of illness, and predisposing conditions are collected.

Acute Physiology, Age, and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) III.

There is strong evidence that severity of illness on admission to the ICU, assessed by APACHE score [37–41], is a risk factor for delirium [1, 42]. APACHE scores are calculated for the first ICU admission day (24 hours of data, beginning at ICU admission).

Sequential Organ Failure Score (SOFA).

To determine daily severity of illness we use the SOFA [43], which was developed to quantify severity of illness based on the degree of organ dysfunction, serially over time. The SOFA score has good reliability and accuracy [43], accurately reflects the daily severity of organ dysfunction, predicts prognosis [44] and is able to predict ICU mortality [45]. We calculate a SOFA score for each ICU day after enrollment, for a total of up to 7 days.

STOP-Bang Model (SBM) Assessment.

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) underlies numerous co-morbidities and is linked with cardiovascular and neurovascular diseases, metabolic disorders, and impaired neurocognitive function [46–48]. The STOP-Bang Model (SBM) questionnaire is used as an OSA screening tool for baseline data collection based on the LAR’s subjective report.

Subject Demographics.

Subject characteristics that may affect the development of delirium are collected at admission to the study, including age, sex, and race/ethnicity [42]. Age has been identified as a strong risk for delirium, but it should be noted that in a recent meta-analysis of risk factors for delirium in the ICU (n = 33 studies), none of the 12 research studies which examined gender as a risk factor found evidence of an association with gender [42]. Nonetheless, we include age, gender, race, and ethnicity in our examination of moderators of the FAVoR intervention.

Additional Subject Descriptive Data.

In order to completely describe the study population, we also collect the type of ICU (reflecting type of critical illness and population, i.e., surgical, medical, neurological, cardiovascular, or trauma ICU). Families or significant others are also asked if the patient had any documented impairment in vision or hearing.

Patient-Reported Health Status.

The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) is a publicly available, standardized system of highly reliable, precise measures of patient-reported health status for physical, mental, and social well-being. In this study, the PROMIS questionnaires evaluate self-reported global health (PROMIS Global Health), sleep (Sleep Disturbances, Sleep-Related Impairment), and cognitive function (Cognitive Function, and Cognitive Function Abilities) [49–52]. We collect these data after transferring out of the ICU, and at 1 month and 6 months following hospital discharge.

Cognitive Function.

The NIH Toolbox Cognition Battery [53] testing is used to assess cognitive function after transferring out of the ICU, and at 1 month and 6 months following hospital discharge.

Data Collection Procedures.

Data are obtained both inpatient and outpatient from the subject’s medical record, non-invasive physiologic monitoring, cognitive testing, and observation. The data collection schedule is shown in Table 1 and procedures are described below. Each subject is assigned with an arbitrary study identification number, and no individually identifiable private information is entered into the study database. Only study personnel who are responsible for enrollment and data collection have access to individually identifiable information. Data assessors are blinded to group assignments.

Table 1.

Key Variables and Data Collection

| Concept | Measure | Data Collection Time Points |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 hours Pre-Study | Study Admission | ICU Days 1–5 | ICU Days 6–7 | 24–72 hours Post-ICU Discharge | 1 Month Post-Hospital Discharge | 6 Months Post-Hospital Discharge | ||

| Delirium | ||||||||

| ICU delirium | CAM-ICU 7 | • | • | • | ||||

| Post-ICU delirium | CAM | • | • | • | ||||

| Provider report of delirium | Documentation of delirium | • | • | • | • | • | ||

| Activity/Sleep | Actigraphy | • | • | • | • | • | ||

| SP-PSG | • | • | • | • | • | |||

| Iatrogenic, Environmental, and Biobehavioral Factors | ||||||||

| Ambient light | Actigraphy | • | • | • | • | • | ||

| Pharmacological therapies affecting sleep and/or cognition | Drug type and cumulative sedative dose | • | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| Disease severity and comorbid conditions | APACHE III | • | ||||||

| STOP-BANG | • | |||||||

| SOFA | • | • | • | |||||

| Demographic characteristics | Age, sex, race/ethnicity | • | ||||||

| Patient-reported Health Status | PROMIS Global Health | • | • | • | ||||

| Patient-reported Sleep Quality | PROMIS-SD | • | • | • | ||||

| PROMIS-SRI | • | • | • | |||||

| Patient-reported Cognitive Function | PROMIS-CF | • | • | • | ||||

| PROMIS-CFA | • | • | • | |||||

| Cognitive Function | NIH Toolbox Cognition Battery | • | • | • | ||||

Note.

CAM-ICU 7: Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit 7.

CAM: Confusion Assessment Method.

SP-PSG: Sleep Profiler polysomnography.

APACHE III: Acute Physiology, Age, and Chronic Health Evaluation III.

STOP-BANG: STOP-BANG Questionnaire.

SOFA: Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

PROMIS: Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System.

PROMIS-SD: Sleep Disturbance.

PROMIS-SRI: Sleep Related Impairment.

PROMIS-CF: Cognitive Function.

PROMIS-CFA: Cognitive Function Abilities.

NIH Toolbox: National Institutes of Health Toolbox.

Inpatient.

Once consent is obtained and the subject is enrolled, baseline data are collected from medical records. The family member selected by the family to record scripted FAVoR messages is escorted to a quiet area to complete the recording on the assigned laptop for both intervention and control group. After recording the family member’s voice, blinded CAM-ICU assessment is completed on the subject prior to opening the randomization envelope. If the subject is randomized to the intervention group, then the recorded messages are further edited for quality and saved on a wireless speaker for intervention delivery. The FAVoR intervention is delivered through a speaker, which is placed near the patient’s head. If the subject is randomized to the FAVoR intervention group, then the delivery of the intervention begins as soon as possible before 4:00 PM. If the patient was enrolled after 4:00 PM, then the first “dose” of the intervention will be delivered on the following morning at 9:00 AM. Data recording devices (SP-PSG and Actiwatch) are applied to all subjects (regardless of group randomization) as soon as feasible following consent, and continue for up to 120 continuous hours of recording, or until ICU discharge if less than 5 days. The post-ICU visit occurs within a time window of 24 to 72 hours following ICU discharge. At the follow-up post-ICU visit, the subject completes the NIH Toolbox Cognition Battery, the PROMIS Global Health instrument, the PROMIS Sleep Disturbance and Sleep-Related Impairment instruments. In addition, actigraphy and SP-PSG are obtained for a 24-hour period. Contact information is again obtained from the subject at this time, in order to schedule home visits (described below) at 1 month and 6 months.

Outpatient.

There are two outpatient data collection events, at 1 month and 6 months post-hospital discharge. During the 1-month home visit, research personnel travel to the subject’s home (or other agreed-upon location) to administer the NIH Toolbox Cognition Battery and the PROMIS assessments. The subject is also asked to wear the SP-PSG and Actiwatch (for acquisition of sleep and activity data) overnight. Research personnel return the following day to pick up the devices and schedule the 6-month data collection visit. Identical data collection processes are used at the final 6-month visit.

Compensation.

Upon the hospital discharge date, a gift card in the amount of $25, along with a note of thanks to the participant and their family, is mailed to the home address of the participant. A second gift card valued in the amount of $25 is hand delivered during the final home visit, approximately 6 months after the hospital discharge date.

Data Management

All data are downloaded into Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap), a secure web application database, which is accessed by a secure web connection with authentication and data logging. At the beginning of the data entry process, a minimum of 1 in every 10 participant records are checked against the original medical record for data errors. Records for review are randomly chosen by the Data Manager. As the study progresses, the frequency of monitoring is based on the results of the previous data review. If the error rate is unacceptable, then monitoring increases until the error rate is acceptable (less than 5% of all data). The Data Manager in consultation with the Principal Investigator develops monthly reports that help in the coordination and management of the project and also allow project staff to monitor the quality of the data and the progress of the study. Furthermore, only a unique identifier, assigned by the Principal Investigator or Data Manager, in the database identified each subject. The data files are backed up daily during the data entry process and once a week during other times by the Project Director. All data files are housed on the university’s server, which is backed up every 24 hours, and copies are stored off-site for additional security. Access to the database is password-protected and limited to the investigators, Project Director, and Data Manager.

Data Analysis Plan

There will be two parts of the data analysis. Part 1 will involve traditional statistical data analyses for randomized controlled trials for the primary specific aim. Part 2 will utilize pathway analytic model analyses to address the secondary aims. Our statistician will work closely with our Data Manager to perform all the planned data analyses for this study.

Part 1.

We will follow the research and regulatory guidelines for statistical analysis of clinical trials and the CONSORT guidelines [54]. First, descriptive statistics will be performed to describe and compare the characteristics of the intervention and the control groups. Descriptive statistics will be reported as means +/− standard deviation for continuous variables, and as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Shapes of the data distributions, missing data and outliers will be examined by both graphics and statistical tests. Any data issues identified will be discussed with the PI and other investigators, and will be addressed before formal data analysis. For example, skewed variables may be transformed so that their distributions are close to normal distribution. Outliers may be excluded or included in two separate analyses. Missing data may be imputed or handled by other missing data techniques. Distributions of continuous variables and categorical variables will be compared between the intervention and the control group by using the t-test or Wilcoxon rank sum test and the Chi-square test, respectively. Any baseline covariate that is differentially distributed in the two groups will be adjusted in the subsequent analysis for testing the intervention effect. Assuming the randomization produces well-balanced intervention and control groups, a Chi-square test for a 2 × 2 table with the number of delirium-free days and the treatment assignment will be performed to test the primary hypothesis. If there are unbalanced covariates, then covariance adjustment will be performed by using logistic regression that includes both the treatment assignment and the unbalanced covariates. If there are missing values in the primary outcome, then multiple imputation will be performed using SAS PROC MI (SAS Institute) for missing at random (MAR) data [55]. Sensitivity analysis for potentially not missing at random data will be performed using the Little and Yau [56] Intent-to-Treat Analysis for Longitudinal Studies with Dropouts.

Part 2.

Given the large number of variables measured for activity/sleep, disease severity, environment and demographics and the potential complex pathways among these variables, we plan to use partial least squares structural equation models (PLS-SEM) to analyze the relative importance and the pathways of these variables. Partial least squares (PLS) is a predictive modeling method that can predict high dimensional outcomes from high dimensional, correlated predictors. The variance importance in projection (VIP) measure in PLS models can be used to compare the relative importance of different predictors, which is a useful tool for variable selection in high dimensional data [57]. In recent years, PLS-SEM was developed to use PLS fit pathway models with both manifested and latent variables [58–61]. PLS-SEM is implemented in the R package semPLS. We will perform the predictive PLS using SAS PROC PLS for variable screening, so that important predictors from the high dimensional raw data (such as the sleep measures) will be identified. Then, we will fit PLS-SEM using the R package semPLS to the mediation effect of sleep and other empirically or theoretically hypothesized pathways. Specifically, for secondary aim 1, we will perform meditation analysis within multilevel SEM. For secondary aim 2, we will test moderation in PLS-SEM to test the biobehavioral factors as multiple moderators. Finally, for secondary aim 3, we will fit path analytic models from the FAVoR intervention to the short-term and the long-term cognitive function and patient-reported health status measures, respectively. Study Timeline. Please see Table 2.

Table 2.

Study Timeline

| Activity | Year | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Year 4 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Months | 1–4 | 5–8 | 9–12 | 1–4 | 5–8 | 9–12 | 1–4 | 5–8 | 9–12 | 1–4 | 5–8 | 9–12 | |

| Hire/train personnel | |||||||||||||

| Database refinement | |||||||||||||

| Recruitment and enrollment | |||||||||||||

| Subject 1- and 6-months follow-up | |||||||||||||

| Data collection | |||||||||||||

| Data management | |||||||||||||

| Analysis of final results | |||||||||||||

| Final results manuscript | |||||||||||||

| Final grant report | |||||||||||||

Discussion

Delirium in the ICU is a common problem for critically ill, MV patients. It increases complications during the hospital stay and is associated with long-term cognitive problems and disability. Our study will be the first to a non-pharmacological, low-cost, easily implemented intervention, which involves the patient’s family to decrease the incidence of delirium. The findings of the study will provide guidance on family involvement in the ICU setting to prevent ICU delirium and its associated complications.

Additionally, the FAVoR Study is enrolling a diverse sample of English- and Spanish-speaking MV ICU patients, with over half of our sample identifying as Hispanic/Latino as Hispanics/Latinos account for 68% of our population. The FAVoR Study also enrolls patients across two large academic hospitals, including a Level 1 trauma center and a public trust hospital, with enrollments from 9 different ICUs.

We also approached our study aims with innovative methods. The CAM-ICU 7 assesses severity of delirium and tracks the effectiveness of the FAVoR intervention over time in the ICU. We will examine the short-term and long-term effects of FAVoR intervention on cognition following ICU discharge, and at 1 month and 6 months after hospital discharge, using a comprehensive battery of cognition assessments. Additionally, we will explore whether the FAVoR intervention’s effect on delirium is mediated by sleep. We use two objective measures of sleep, polysomnography and actigraphy, in this critically ill population.

Study Challenges

To date, we have enrolled and randomized 175 subjects. Significant challenges have been posed by the COVID-19 pandemic beginning in March 2020. As a result of COVID-19, both institutions where recruitment was occurring paused human subjects research, resulting in a 4-month hiatus in enrollment. In June 2020, recruitment resumed at one of the two sites, excluding patients with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19. Consent procedures have been limited to remote contact of family members/LARs, and ICU visiting hours have been eliminated for family members. Follow-up visits must also be conducted remotely via HIPAA-compliant Zoom or telephone, requiring adjustment of measures at the 1-month and 6-month timepoints. We have also encountered instances of resistance from family to the patient wearing the SP-PSG device throughout the ICU study period, which will increase our reliance on actigraphy data for sleep assessment.

Conclusion

Delirium in critically ill MV adults is an important unresolved issue and carries significant impact on patient outcomes. The FAVoR intervention expands on the ABCDEF bundle guidelines recommending frequent reorientation and family involvement in ICU care [62]. Dissemination of results from this trial will directly address the gap in the evidence for prevention and treatment of delirium in critical care nursing, and will enable evidence-based selection of non-pharmacological interventions in critically ill MV adults in the ICU.

Acknowledgement:

The study is funded by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Nursing Research (R01NR016702).

Footnotes

Trial registration: NCT03128671

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: Please see attachments.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Zhang Z, Pan L, Ni H: Impact of delirium on clinical outcome in critically ill patients: a meta-analysis. General hospital psychiatry 2013, 35(2):105–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ely EW, Shintani A, Truman B, Speroff T, Gordon SM, Harrell FE Jr., Inouye SK, Bernard GR, Dittus RS: Delirium as a predictor of mortality in mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit. Jama 2004, 291(14):1753–1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pisani MA, Kong SY, Kasl SV, Murphy TE, Araujo KL, Van Ness PH: Days of delirium are associated with 1-year mortality in an older intensive care unit population. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 2009, 180(11):1092–1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shehabi Y, Riker RR, Bokesch PM, Wisemandle W, Shintani A, Ely EW: Delirium duration and mortality in lightly sedated, mechanically ventilated intensive care patients. Critical care medicine 2010, 38(12):2311–2318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, Ely EW, Gelinas C, Dasta JF, Davidson JE, Devlin JW, Kress JP, Joffe AM et al. : Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Critical care medicine 2013, 41(1):263–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinhouse GL, Schwab RJ, Watson PL, Patil N, Vaccaro B, Pandharipande P, Ely EW: Bench-to-bedside review: delirium in ICU patients - importance of sleep deprivation. Critical care (London, England) 2009, 13(6):234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin WL, Chen YF, Wang J: Factors Associated With the Development of Delirium in Elderly Patients in Intensive Care Units. The journal of nursing research : JNR 2015, 23(4):322–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gunther ML, Morandi A, Krauskopf E, Pandharipande P, Girard TD, Jackson JC, Thompson J, Shintani AK, Geevarghese S, Miller RR 3rd et al. : The association between brain volumes, delirium duration, and cognitive outcomes in intensive care unit survivors: the VISIONS cohort magnetic resonance imaging study*. Critical care medicine 2012, 40(7):2022–2032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morandi A, Rogers BP, Gunther ML, Merkle K, Pandharipande P, Girard TD, Jackson JC, Thompson J, Shintani AK, Geevarghese S et al. : The relationship between delirium duration, white matter integrity, and cognitive impairment in intensive care unit survivors as determined by diffusion tensor imaging: the VISIONS prospective cohort magnetic resonance imaging study*. Critical care medicine 2012, 40(7):2182–2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van den Boogaard M, Schoonhoven L, Evers AW, van der Hoeven JG, van Achterberg T, Pickkers P: Delirium in critically ill patients: impact on long-term health-related quality of life and cognitive functioning. Critical care medicine 2012, 40(1):112–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jackson JC, Ely EW: Cognitive impairment after critical illness: etiologies, risk factors, and future directions. Seminars in respiratory and critical care medicine 2013, 34(2):216–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Girard TD, Jackson JC, Pandharipande PP, Pun BT, Thompson JL, Shintani AK, Gordon SM, Canonico AE, Dittus RS, Bernard GR et al. : Delirium as a predictor of long-term cognitive impairment in survivors of critical illness. Critical care medicine 2010, 38(7):1513–1520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolters AE, van Dijk D, Pasma W, Cremer OL, Looije MF, de Lange DW, Veldhuijzen DS, Slooter AJ: Long-term outcome of delirium during intensive care unit stay in survivors of critical illness: a prospective cohort study. Critical care (London, England) 2014, 18(3):R125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schulte PJ, Warner DO, Martin DP, Deljou A, Mielke MM, Knopman DS, Petersen RC, Weingarten TN, Warner MA, Rabinstein AA et al. : Association Between Critical Care Admissions and Cognitive Trajectories in Older Adults. Critical care medicine 2019, 47(8):1116–1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, Morandi A, Thompson JL, Pun BT, Brummel NE, Hughes CG, Vasilevskis EE, Shintani AK et al. : Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. The New England journal of medicine 2013, 369(14):1306–1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Qadheeb NS, Balk EM, Fraser GL, Skrobik Y, Riker RR, Kress JP, Whitehead S, Devlin JW: Randomized ICU trials do not demonstrate an association between interventions that reduce delirium duration and short-term mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Critical care medicine 2014, 42(6):1442–1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Treloar DM, Nalli BJ, Guin P, Gary R: The effect of familiar and unfamiliar voice treatments on intracranial pressure in head-injured patients. The Journal of neuroscience nursing : journal of the American Association of Neuroscience Nurses 1991, 23(5):295–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walker JS, Eakes GG, Siebelink E: The effects of familial voice interventions on comatose head-injured patients. Journal of trauma nursing : the official journal of the Society of Trauma Nurses 1998, 5(2):41–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tavangar H, Shahriary-Kalantary M, Salimi T, Jarahzadeh M, Sarebanhassanabadi M: Effect of family members’ voice on level of consciousness of comatose patients admitted to the intensive care unit: A single-blind randomized controlled trial. Advanced biomedical research 2015, 4:106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salluh JI, Wang H, Schneider EB, Nagaraja N, Yenokyan G, Damluji A, Serafim RB, Stevens RD: Outcome of delirium in critically ill patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2015, 350:h2538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Munro CL, Cairns P, Ji M, Calero K, Anderson WM, Liang Z: Delirium prevention in critically ill adults through an automated reorientation intervention - A pilot randomized controlled trial. Heart & lung : the journal of critical care 2017, 46(4):234–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Efird J: Blocked randomization with randomly selected block sizes. International journal of environmental research and public health 2011, 8(1):15–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grap MJ, Blecha T, Munro C: A description of patients’ report of endotracheal tube discomfort. Intensive & critical care nursing 2002, 18(4):244–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Granja C, Lopes A, Moreira S, Dias C, Costa-Pereira A, Carneiro A: Patients’ recollections of experiences in the intensive care unit may affect their quality of life. Critical care (London, England) 2005, 9(2):R96–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roberts BL, Rickard CM, Rajbhandari D, Reynolds P: Factual memories of ICU: recall at two years post-discharge and comparison with delirium status during ICU admission--a multicentre cohort study. Journal of clinical nursing 2007, 16(9):1669–1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ely EW, Inouye SK, Bernard GR, Gordon S, Francis J, May L, Truman B, Speroff T, Gautam S, Margolin R et al. : Delirium in mechanically ventilated patients: validity and reliability of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU). Jama 2001, 286(21):2703–2710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khan BA, Perkins AJ, Gao S, Hui SL, Campbell NL, Farber MO, Chlan LL, Boustani MA: The Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU-7 Delirium Severity Scale: A Novel Delirium Severity Instrument for Use in the ICU. Critical care medicine 2017, 45(5):851–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Devlin JW, Skrobik Y, Gelinas C, Needham DM, Slooter AJC, Pandharipande PP, Watson PL, Weinhouse GL, Nunnally ME, Rochwerg B et al. : Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Pain, Agitation/Sedation, Delirium, Immobility, and Sleep Disruption in Adult Patients in the ICU. Critical care medicine 2018, 46(9):e825–e873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones RN, Cizginer S, Pavlech L, Albuquerque A, Daiello LA, Dharmarajan K, Gleason LJ, Helfand B, Massimo L, Oh E et al. : Assessment of Instruments for Measurement of Delirium Severity: A Systematic Review. JAMA Internal Medicine 2019, 179(2):231–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neto AS, Nassar AP Jr., Cardoso SO, Manetta JA, Pereira VG, Esposito DC, Damasceno MC, Slooter AJ: Delirium screening in critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Critical care medicine 2012, 40(6):1946–1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levendowski DJ, Popovic D, Berka C, Westbrook PR: Retrospective cross-validation of automated sleep staging using electroocular recording in patients with and without sleep disordered breathing. International archives of medicine 2012, 5(1):21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stepnowsky C, Levendowski D, Popovic D, Ayappa I, Rapoport DM: Scoring accuracy of automated sleep staging from a bipolar electroocular recording compared to manual scoring by multiple raters. Sleep medicine 2013, 14(11):1199–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jean R, Shah P, Yudelevich E, Genese F, Gershner K, Levendowski D, Martillo M, Ventura I, Basu A, Ochieng P et al. : Effects of deep sedation on sleep in critically ill medical patients on mechanical ventilation. Journal of sleep research 2019:e12894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schwab KE, Ronish B, Needham DM, To AQ, Martin JL, Kamdar BB: Actigraphy to Evaluate Sleep in the Intensive Care Unit. A Systematic Review . Annals of the American Thoracic Society 2018, 15(9):1075–1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwab KE, To AQ, Chang J, Ronish B, Needham DM, Martin JL, Kamdar BB: Actigraphy to measure physical activity in the intensive care unit: A systematic review. J Intensive Care Med 2019:885066619863654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tracy MF, Chlan L, Savik K, Skaar DJ, Weinert C: A Novel Research Method for Determining Sedative Exposure in Critically Ill Patients. Nurs Res 2019, 68(1):73–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Knaus WA, Zimmerman JE, Wagner DP, Draper EA, Lawrence DE: APACHE-acute physiology and chronic health evaluation: A physiologically based classification system. Critical care medicine 1981, 9(8):591–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE: APACHE II: A severity of disease classification system. Critical care medicine 1985, 13(10):818–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Knaus WA, Wagner DP, Draper EA, Zimmerman JE, Bergner M, Bastos PG, Sirio CA, Murphy DJ, Lotring T, Damiano A et al. : The APACHE III prognostic system. Risk prediction of hospital mortality for critically ill hospitalized adults. Chest 1991, 100(6):1619–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mok SR, Mohan S, Elfant AB, Judge TA: The acute physiology and chronic health evaluation IV, a new scoring system for predicting mortality and complications of severe acute pancreatitis. Pancreas 2015, 44(8):1314–1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Giangiuliani G, Mancini A, Gui D: Validation of a severity of illness score (APACHE II) in a surgical intensive care unit. Intensive care medicine 1989, 15(8):519–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zaal IJ, Devlin JW, Peelen LM, Slooter AJ: A systematic review of risk factors for delirium in the ICU. Critical care medicine 2015, 43(1):40–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, Willatts S, De Mendonca A, Bruining H, Reinhart CK, Suter PM, Thijs LG: The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the Working Group on Sepsis-Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive care medicine 1996, 22(7):707–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oda S, Hirasawa H, Sugai T, Shiga H, Nakanishi K, Kitamura N, Sadahiro T, Hirano T: Comparison of Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score and CIS (cellular injury score) for scoring of severity for patients with multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS). Intensive care medicine 2000, 26(12):1786–1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khwannimit B: Serial evaluation of the MODS, SOFA and LOD scores to predict ICU mortality in mixed critically ill patients. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand = Chotmaihet thangphaet 2008, 91(9):1336–1342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jennum P, Riha RL: Epidemiology of sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome and sleep-disordered breathing. The European respiratory journal 2009, 33(4):907–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McNicholas WT, Bonsigore MR: Sleep apnoea as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease: current evidence, basic mechanisms and research priorities. The European respiratory journal 2007, 29(1):156–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Farney RJ, Walker BS, Farney RM, Snow GL, Walker JM: The STOP-Bang equivalent model and prediction of severity of obstructive sleep apnea: relation to polysomnographic measurements of the apnea/hypopnea index. Journal of clinical sleep medicine : JCSM : official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine 2011, 7(5):459–465b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, Gershon R, Cook K, Reeve B, Ader D, Fries JF, Bruce B, Rose M: The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): progress of an NIH Roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Medical care 2007, 45(5 Suppl 1):S3–s11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Revicki DA, Spritzer KL, Cella D: Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items. Quality of life research: an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation 2009, 18(7):873–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yu L, Buysse DJ, Germain A, Moul DE, Stover A, Dodds NE, Johnston KL, Pilkonis PA: Development of short forms from the PROMIS sleep disturbance and Sleep-Related Impairment item banks. Behavioral sleep medicine 2011, 10(1):6–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lai JS, Wagner LI, Jacobsen PB, Cella D: Self-reported cognitive concerns and abilities: two sides of one coin? Psycho-oncology 2014, 23(10):1133–1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weintraub S, Dikmen SS, Heaton RK, Tulsky DS, Zelazo PD, Bauer PJ, Carlozzi NE, Slotkin J, Blitz D, Wallner-Allen K et al. : Cognition assessment using the NIH Toolbox. Neurology 2013, 80(11 Suppl 3):S54–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D: CONSORT 2010 statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Journal of pharmacology & pharmacotherapeutics 2010, 1(2):100–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Little RJA, Rubin DB: Statistical Analysis with Missing Data, 3 edn. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Little RJA, Yau L: Intent-to-treat analysis for longitudinal studies with drop-outs. Biometrics 1996, 52(4):1324–1333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Esposito Vinz V, Chin WW, Henseler J, Wang H: Handbook of Partial Least Squares: Concepts, Methods and Applications. Berlin Heidelberg Spinger-Verlag; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sarstedt M, Ringle CM, Smith D, Reams R, Hair JF: Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): A useful tool for family business researchers. Journal of Family Business Strategy 2014, 5(1):105–115. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hair JF, Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M: A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM).. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lowry PB, Gaskin J: Partial Least Squares (PLS) Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) for Building and Testing Behavioral Causal Theory: When to Choose It and How to Use It. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication 2014, 57(2):123–146. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Monecke A, Leisch F: semPLS: Structural Equation Modeling Using Partial Least Squares.. Journal of Statistical Software 2012, 48:1–32. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pun BT, Balas MC, Barnes-Daly MA, Thompson JL, Aldrich JM, Barr J, Byrum D, Carson SS, Devlin JW, Engel HJ et al. : Caring for Critically Ill Patients with the ABCDEF Bundle: Results of the ICU Liberation Collaborative in Over 15,000 Adults. Critical care medicine 2019, 47(1):3–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]