Abstract

Rosai–Dorfman disease (RDD) is a rare and self-limiting disease process that presents most commonly in young patients as massive, painless, cervical lymphadenopathy. Extranodal involvement may also occur. Histopathologic evaluation is the main diagnostic modality. We report an unusual presentation of RDD with cervical lymphadenopathy and an incidentally discovered sinonasal mass, clinically worrisome for malignancy. We emphasize that a high index of clinical suspicion is critical for accurate diagnosis of RDD. Clinicians and pathologists should consider RDD in a differential diagnosis of cervical lymphadenopathy, especially in young patients.

Keywords: Rosai–Dorfman disease, Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy, Cervical lymphadenopathy, Emperipolesis, Sinonasal mass, Immunohistochemistry, Lymphophagocytosis

Introduction

Also known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy, Rosai–Dorfman disease (RDD) was first described in 1969 by Rosai and Dorfman [1]. It is a self-limiting histiocytic disease with unknown etiology. Non-tender, painless lymphadenopathy in young patients, usually in the first or second decades of life, is characteristic. Extranodal involvement is seen in less than half of the cases. Histopathologic evaluation is the core diagnostic method.

Case Report

A 2-year-old girl presented with a progressive, painless swelling of the left neck of two months duration. There was no significant past medical history or recent history of upper respiratory tract infection. Constitutional signs and symptoms such as fever, night sweats, malaise, and weight loss were not present, and there was no evidence of environmental, travel-related, animal, or insect exposures. Chronic medication use and infectious exposures were not reported by the parents. There was no recent immunization. There was no history of nasal obstruction, epistaxis, mass protrusion, mouth breathing, snoring, or apnoeic episodes during sleep.

The patient was admitted to another center for 2 weeks and underwent antibiotic therapy with cloxacillin, vancomycin, and meropenem. The neck mass was aspirated and sent for pathologic evaluation but the results were inconclusive due to poor sample handling and processing. The possibility of a non-specific inflammatory process, however, was suggested.

When the patient visited our center, she was ill with a high fever (39.5 °C). Other vital signs included a pulse rate of 134/min, respiratory rate of 42/min, and blood pressure of 90/60 mmHg. She was alert and cooperative during the physical examination. A dry mouth and erythematous tonsils without exudate were observed. The ears and eyes were normal. The left submandibular region of the neck had non-tender, non-erythematous bulged nodules that were coalesced and fixed. The physical examination of the heart and lungs was normal. No organomegaly was detected.

Laboratory findings included a complete blood count showing a white blood cell (WBC) absolute count of 13.04 × 109/L (reference interval: 4–10 × 109/L), lymphocyte count of 3.09 × 109/L (reference: 0.8-4 × 109/L), neutrophil count of 7.96 × 109/L (reference: 2–7 × 109/L), monocyte count of 1.40 × 109/L (reference: 0.12–0.8 × 109/L), eosinophil count of 0.56 × 109/L (reference: 0.02–0.5 × 109/L), and platelet count of 711 × 109/L (reference: 150–450 × 109/L). The relative counts of WBCs were as follows: 23.7% lymphocytes (reference: 20–40%), 61.1% neutrophils (reference: 50–70%), 10.7% monocytes (reference: 3–8%), and 4.3% eosinophils (reference: 0.5–5%). The hemoglobin level was 9.1 g/dL (reference interval: 10.5–14.5 g/dL ).

The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 90 mm/h (reference interval: 0–10 mm/h) and the C-reactive protein (CRP) level was 84 mg/L (reference interval < 6 mg/L). The lactate dehydrogenase level 374 IU/L was within the normal range (reference interval: 5–1100 IU/L). Cultures from blood and urine samples were negative. Investigation to detect viral infections including IgM VCA, Mono test, IgM EBV, IgM Toxo, HIV antibody, and IgM CMV were negative. The NBT (Nitroblue tetrazolium) test showed 100% functional neutrophils (reference interval 90–100%). Lab assessments for Mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB), including PPD (7 mm) and TB- PCR assay, were negative. IgM, IgG, and IgA levels were 1458 mg/dL (reference: 295–1156 mg/dL), 161 mg/dl (reference: 37–184 mg/dL), and 1188 (< 135 mg/dL), respectively. Flow cytometry assessment showed 28% CD4, 31% CD8, 99% CD11a, 99% CD11b, 99% CD11c, 65% CD15, 13% CD56, and 100% CD45. Gram staining of the direct smear of the cervical lymph node aspirate showed numerous white blood cells and a moderate number of epithelial cells, but it was negative for bacteria.

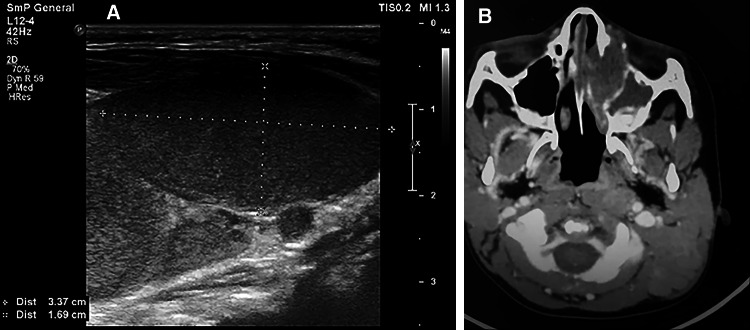

Chest X-ray showed a normal-sized heart, parahilar infiltration, and hyperinflation. Ultrasound examination of the neck revealed multiple enlarged, hypervascular cervical lymph nodes in levels I, II, III, IV, and V, the greatest measuring 3.7 × 1.6 cm. The parotid glands appeared normal (Fig. 1). Abdominal ultrasound showed a liver span of 80 mm (reference range less than 85 mm) and a spleen span of 75 mm (reference range less than 80 mm). Lymphadenopathy outside the cervical region was not detected.

Fig. 1.

a Ultrasonographic view of the cervical lymphadenopathy of the patient with Rosai–Dorfman disease. The largest lymph node measured 3.37 × 1.69 cm. b Axial spiral CT of the patient showing a soft tissue mass occupying the left nasal cavity. Remodeling and erosion of the medial wall of the sphenoid sinus and extension to the anteromedial aspect of the left orbit is appreciated

Head and neck computed tomography (CT) scanning showed extensive lymphadenopathy of the left neck, especially level II and the posterior triangle. One of the lymph nodes demonstrated liquefaction. A soft tissue mass was also incidentally found in the left nasal cavity. This lesion was associated with remodeling and erosion of the medial wall of the sphenoid sinus, and it extended to the anteromedial aspect of the left orbit (Fig. 1). Chest and abdominal CT scans were unremarkable. Bone marrow aspiration and bone marrow biopsy were not performed.

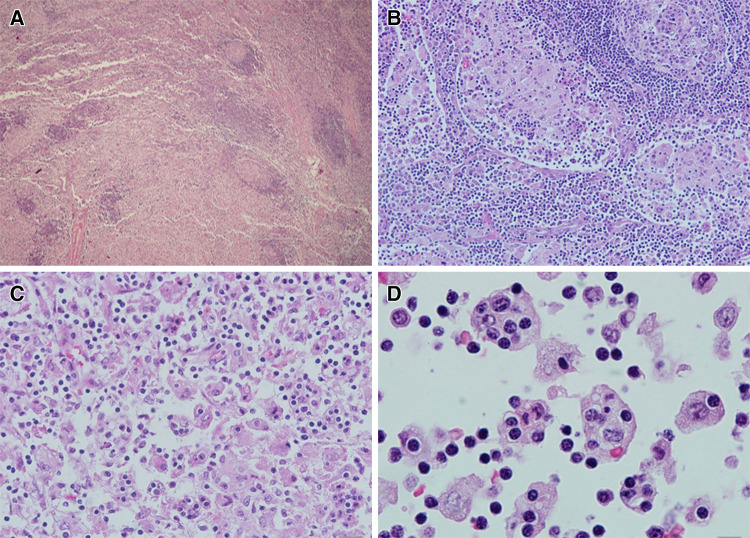

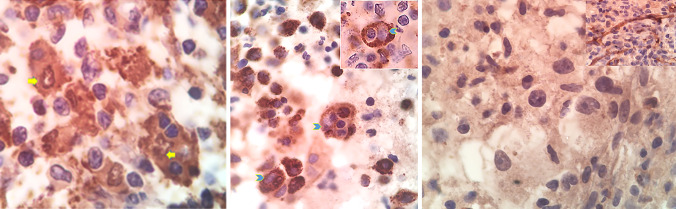

Open excisional biopsy of a cervical lymph node was performed under general anesthesia. The lymph node specimen comprised an intact, encapsulated, 2.8 × 2.0 × 1.0 cm lymph node with vague lobularity on the external surface. The cut surface was tan-gray with no grossly discernable evidence of hemorrhage or necrosis. On microscopic examination, the lymph node showed massive sinusoidal dilation with individual and aggregated, moderate to large histiocytes (Fig. 2). The nuclei of the histiocytic cells were large, round, pale, and vesicular and contained one or two small, eosinophilic nucleoli. Partially marginated chromatin and nuclear clearing were noted. The cytoplasm was abundant and clear to pale pink. Emperipolesis was observed, with a significant number of histiocytes containing hematolymphoid elements, mostly small lymphocytes. Rare phagocytosis of red blood cells and plasma cells was also seen. The cells within the histiocytic cytoplasm appeared intact and were occasionally surrounded by a clear halo. There were many accompanying mononuclear cells including small lymphocytes and occasional plasma cells. Focal eosinophilic and neutrophilic infiltration was seen, especially around vessels. No necrosis, hemorrhage, or cellular atypia were appreciated. Rare mitotic figures were present. The histiocytes were positive for S100 (Fig. 3a) and CD68 and negative for CD1a.

Fig. 2.

Histopathologic findings of a cervical lymph node involved by Rosai–Dorfman disease (hematoxylin and eosin). a Lymph node infiltration by histiocytes with large eosinophilic cytoplasms gives a pinkish hue to the majority of the lymph node. Small foci of increased cellular density and preserved residual nodal architecture are present (magnification × 40). b (magnification × 200) and c (magnification × 400): sinusoidal distribution of pale histiocytes is apparent. d Oil immersion magnification (× 1000) showing the hallmark histologic finding of Rosai–Dorfman disease: large histiocytes with pale, vesicular nuclei engulfing as many as 1 to 8 small lymphocytes (emperipolesis)

Fig. 3.

Oil immersion magnification of the immunohistochemistry findings of Rosai–Dorfman disease. a Positive S100 immunostaining (both cytoplasmic and nuclear) of the histiocytes in the lymph node with emperipolesis of lymphocytes. The arrows mark the S100 positive nuclei of histiocytes. b CD68 immunostaining of the nasal mass, showing strong granular cytoplasmic positivity. The arrows mark the vesicular nuclei of the histiocytes. The inset shows a phagocytosed lymphocyte with a peripheral halo within the cytoplasm of a histiocyte. The pale nucleus of the histiocyte is marked by the arrowhead. c Negative CD1a immunostaining of the histiocytic cells of the nasal mass. The inset shows the positivity of endothelial cells as internal control

Nasal and paranasal sinus endoscopy showed a large, lobulated tumor in the cavum that occluded most of the choanae. The nasal biopsy consisted of multiple pieces of irregular, soft, tan-pinkish tissue. Microscopic examination showed a histiocytic and chronic fibroinflammatory process with focal emperipolesis within histiocytes. The phagocytized cells were most often lymphocytes. The emperipolesis was less conspicuous as compared to the lymph node. Lymphocytes, occasional mature plasma cells, and neutrophils were present. The plasma cells did not contain Russel bodies. Occasional histiocytes were binucleated and many foamy histiocytes were seen in some areas. Necrosis and significant mitotic activity were absent. By immunohistochemistry, the histiocytes showed nuclear and cytoplasmic positivity for S100 protein and granular, cytoplasmic CD68 positivity (Fig. 3b). The histiocytes did not react with CD1a (Fig. 3c).

The constellation of the histomorphologic findings, especially the pale pink islands of histiocytic aggregates and emperipolesis, led to a diagnosis of RDD. The patient did not undergo any associated therapy. After 15-months of follow-up, the patient was doing well, but the neck masses regressed only slightly.

Discussion and Literature Review

Cervical lymphadenopathy is the most common presentation of RDD. Extranodal involvement has been reported in a variety of sites including the head and neck, intracranium, bone, heart, skin, parotid gland, periodontium, orbit, thyroid, breast, and paranasal sinuses [2–19]. Extranodal manifestation of RDD in the nasal cavity, orbit, and parotid without typical initial lymph node involvement is also reported [12, 19, 20].

A clinicopathologic summary of extranodal sinonasal involvement by RDD reported in the literature is listed in Table 1. These cases include 13 males and 10 females ranging in age from 6 to 79 years. The most common presenting features were a neck mass, nasal obstruction, and epistaxis. Loss of vision, proptosis, eye tearing, hoarseness, and hyposmia were also reported [21–25]. Ten out of 23 patients had no lymphadenopathy and four patients experienced lymphadenopathy in sites other than the neck. Nearly all cases had variable numbers of pale-staining histocytes with variable emperipolesis and a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate in a background of fibrosis. Treatment consisted of surgical excision and/or steroids. Follow-up, available for 19 cases including ours, disclosed no evidence of disease progression.

Table 1.

Summary of findings in Rosai–Dorfman disease patient with sinonasal involvement. LAP lymphadenopathy, Yrs years, IHC immunohistochemistry, Dx diagnosis

| Age/ sex | Clinical presentation | LAP | Initial diagnosis | IHC | Treatment | Follow-up | Author | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 64/F | Nasal obstruction | None | Granulomatous inflammation of unknown etiology | Not done | Surgical excision | No recurrence | Wenig et al. [34] | 1993 |

| 42/F | Nasal obstruction for 2 years | None | Aggressive fibromatosis | Not done | Surgical excision | 2 recurrences within 1 year | Wenig et al. [34] | 1993 |

| 22/F | Flu-like symptoms for 2 months, facial and nuchal swelling and tenderness, stridor | Cervical | Langerhans cell histiocytosis | Not done | Surgical excision | Progressive disease | Wenig et al. [34] | 1993 |

| 34/M | Epistaxis for 3 yrs; optic and cochlear nerve deficits | Axillary | Infectious or inflammatory process | Not done | Surgical excision | Persistent disease in the sinonasal area | Wenig et al. [34] | 1993 |

| 39/M | Nasal obstruction, cervical lymphadenopathy fever, facial pain | Cervical | Rhinoscleroma, Gaucher’s disease | Not done | Surgical excision | No recurrence | Wenig et al. [34] | 1993 |

| 69/M | Nasal obstruction | None | Extramedullary plasmacytoma | Not done | Surgical excision | Recurrence after 3 yrs | Wenig et al. [34] | 1993 |

| 51/F | Epistaxis for 2 months | None | Fibrous histiocytoma, infectious disease, malignant lymphoreticular process | Not done | Surgical excision | No recurrence | Wenig et al. [34] | 1993 |

| 57/M | Nasal obstruction for five to six yrs, involvement of the lung and retroperitoneal tissues extending into pancreas and kidneys | None | Malignant fibrous histiocytoma | Not done | Surgical excision | No recurrence after 7 yrs | Gregor et al. [20] | 1994 |

| 10/M | Nasal obstruction, epistaxis, widening of the nasal dorsum | Cervical | – | Not done | Topical and oral corticosteroids and amoxicillin and two months later endoscopic sinus surgery | Nasal airway remained patent during 1 year of follow-up | Goodnight et al. [35] | 1996 |

| 40/M | Nasal obstruction for three months and recurrent epistaxis | None | Extra-pulmonary nasal tuberculosis | S100+ | Surgical excision after unsuccessful anti-TB therapy for 6 months | No recurrence after 2 yrs | Ku et al. [36] | 1999 |

| 10/M | Bilateral painless cervical lymphadenopathy, right-sided nasal obstruction. | Cervical | Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas or tuberculosis | Compatible with RDD | Surgical excision | No recurrence after 3 yrs | Ku et al. [36] | 1999 |

| 49/F | Nasal obstruction, hoarseness anosmia, and lacrimation for 3 months | Cervical | Nasal polyps and chronic sinusitis | – | Tracheotomy 2 yrs after surgical excision | Increasing extranodal tissue formation in upper airway 2 yrs after surgery | Maeda et al. [24] | 2004 |

| 12/M |

Facial asymmetry, bilateral painless cervical and inguinal lymphadenopathy, nasal obstruction and proptosis for 10 months |

Cervical and inguinal | Metastatic malignant small round cell tumor, toxoplasma lymphadenitis, diffuse lymph node hyperplasia | – | Surgical excision | No nasal or orbital recurrence after 18 months | El-Banhawy et al. [22] | 2005 |

| 6/M | Bilateral nasal obstruction for 3 yrs | None | Infection | Not done | Surgical excision | Symptom-free 2 months after surgery | Gupta et al. [37] | 2005 |

| 43/M | Bilateral neck masses, nasal block, weight loss, malaise, evening fever and loss of vision for 6 months. |

Cervical, axillary, and inguinal |

Neck metastases from local malignancies, Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, malignant histiocytosis and monocytic leukemia |

Not done | Corticosteroid therapy | Slow improvement after 6 months with persistent adenopathy | Pinto [21] | 2008 |

| 43/F | Progressive left nasal obstruction, epistaxis, and pain for 6 months | None | Granulomatous process, including rhinoscleroma, Hodgkin lymphoma, carcinoma, and recurrent rhinoscleroma. | S100+, CD68+ | – | – | Ilie et al. [19] | 2010 |

| 79/F | Nasal obstruction and hyposmia, cervical LAP | – | – | S100+, CD68+, α1 antitrypsin+ | – | – | Belcadhi et al. [25] | 2010 |

| 30/F | Right nasal blockade and eye protrusion for 2 years, vision attenuation for 6 months. bilateral nasal discharge for ten years, | None | – | S100+ | Nasal mass surgical excision, CVP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisolone) therapy | – | Khan et al. [38] | 2011 |

| 79/F | Nasal obstruction and epistaxis for 2 yrs | Submandibular | Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (nasal mass biopsy) | S100+, CD30−, ALK−,CD1a−, CK− | – | – | Shi et al. [30] | 2011 |

| 17/M | Nasal obstruction, asthenia, and fever for 3-months | Cervical and axillary | – |

S100+, CD68+, CD1a− |

Corticosteroid therapy | Slow improvement | Ribeiro et al. [27] | 2016 |

| 8/M | Left nasal block for 4 months and epistaxis | Cervical | – | – | Oral steroid and low dose cyclophosphamide | No recurrence or residual disease at 20 months follow up | Ashish et al. [39] | 2016 |

| 10/M | Left epiphora for 6-months from an aggressive paranasal mass invading the left orbit with osseous destruction | None | – | CD68+, S-100+, CD1a−, Desmin−, EBV− | Left orbitotomy for debulking | Asymptomatic at 3-month follow-up | Hur et al. [23] | 2017 |

| 2/F | Left neck mass for 2 months, incidentally found nasal mass in CT scanning | Cervical | Infection, lymphoma |

S100+, CD68+, CD1a− |

Surgical excision | No recurrence after 15 months | Present case | Present case |

In many cases, as in ours, the diagnosis was not made in the first instance due to its rarity and histologic resemblance to other etiologies. The initial diagnoses comprised both benign and malignant entities. Non-malignant conditions included infection, granulomatous inflammation including tuberculosis, fibromatosis, toxoplasma lymphadenitis, Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), rhinoscleroma, Gaucher’s disease, fibrous histiocytoma, diffuse lymph node hyperplasia, and inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. Suspected malignant conditions included Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas, extramedullary plasmacytoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, metastatic malignant small round cell tumor, Hodgkin lymphoma, malignant histiocytosis, monocytic leukemia, and metastatic carcinoma.

As indicated in previous reports, emperipolesis was less amenable to detection in the extranodal site as compared to the lymph node in our case [8, 19]. This could be due to extensive fibrosis or the paucity of pathognomonic histiocytic cells in the extranodal site. Either scenario may lead to confusion and interpretation of the biopsy or fine needle aspirate (FNA) as non-specific inflammatory entities. In the present case, the earlier diagnosis of RDD in the lymph node facilitated interpretation of the sinonasal sample.

According to the American Academy of Family Physicians, ultrasonography should be used as the initial imaging modality for children up to 14 years presenting with a neck mass with or without fever (evidence rating C) [26]. This modality revealed extensive involvement of multiple cervical lymph nodes in our patient (Fig. 1).

Subsequent CT revealed extensive cervical lymphadenopathy as well as a left nasal cavity mass with remodeling and erosion of the medial wall of the sphenoid sinus and extension to the anteromedial aspect of the left orbit. In general, imaging studies such as CT and MRI are useful for evaluating the extent of RDD, but specific characteristics are lacking [27, 28].

Some researchers consider FNA cytology an important modality in the diagnosis of RDD that may be conclusive in a typical clinical setting [15, 29–31]. In a case report by El-Banhawy et al., however, the cytology specimen from a lymph node was incorrectly interpreted as a metastatic malignant small round cell tumor of childhood [22]. In our case, a FNA performed at another center was not diagnostic which may be partially attributed to a low index of clinical suspicion. In a review of 49 FNAs performed in RDD patients, Shi, Y. found that misdiagnosis more often occurs in extranodal sites as compared to nodal disease (50% vs. 12%) [30].

The main differential diagnoses of cervical lymphadenopathy are malignancy, infection, and autoimmune disorders, as well as medications and iatrogenic causes. In our case, infectious and autoimmune etiologies, such as rhinoscleroma and Wegener’s granulomatosis, were ruled out through clinical and laboratory investigations.

Lymphoreticular malignancies such as Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas, malignant histiocytosis, and monocytic leukemia were considered the most probable diagnoses. All of these neoplasms have similar clinical findings and overlapping histopathologic features. In the pediatric age group, special attention should be given to LCH. LCH is S-100, CD1a, and langerin positive by immunohistochemical (IHC) staining, and emperipolesis is not a feature. While S100 may be expressed by both entities, CD1a is expressed in LCH but not in RDD. There are rare reports of LCH co-existing with RDD which may imply a relationship between these two histiocytic disorders [32]. Our case demonstrated almost complete nuclear and cytoplasmic staining of all histiocytes for S100 and no reactivity for CD1a. On occasion, Hodgkin lymphoma lacunar cells may be confused with RDD histiocytes; however, as in LCH, emperipolesis is not present. Atypia in cytology and the aggressive clinical course establish the diagnosis in most cases.

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor or inflammatory pseudotumor of the paranasal sinuses is another potential diagnosis that primarily occurs in childhood. Lesions are composed of spindled myofibroblasts with a mixed inflammatory infiltrate of plasma cells, lymphocytes, and eosinophils. Lack of these features and the presence of characteristic pathologic findings of RDD lead us to the appropriate diagnosis.

The etiology of RDD is not known. It is thought to be a disorder of immune regulation in response to an infectious agent such as Epstein–Barr virus (EBV). Upper respiratory tract infection and subsequent cervical lymphadenopathy frequently occurs in the pediatric population. Post-vaccination lymphadenopathy also is common in this age group. Our patient did not report upper respiratory tract infection or other conditions before the development of cervical lymphadenopathy. We did not identify any potential etiologic agents through the clinical and laboratory workup.

There is no globally agreed-upon protocol for treating RDD, but it is self-limiting and seldom life-threatening. Therapy is unnecessary in most cases. For patients with persistent, worsening, or life-threatening symptoms such as airway obstruction, treatment modalities may include surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy. None of these treatments are reported to dependably attain persistent remission, however [22, 33]. In our case, no treatment was given after the diagnosis was rendered.

Conclusions

In summary, we report a case of RDD with massive cervical lymphadenopathy. Radiographic studies revealed extranodal, sinonasal involvement. The diagnosis was delayed because of a low index of clinical suspicion on first admission. Although history, physical examination, laboratory investigation, and imaging studies helped to rule out other potential diagnoses, the definitive diagnosis was made upon histopathologic examination of a lymph node biopsy. Although rare, RDD should be included in the differential diagnosis of cervical lymphadenopathy, especially in the pediatric age group.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Aileen Azari-Yaam, Email: azari_yam@sina.tums.ac.ir, Email: aileenazariyam@gmail.com.

Mohammad Reza Abdolsalehi, Email: Drmabdosalehi@gmail.com.

Mohammad Vasei, Email: mvasei@tums.ac.ir.

Moeinadin Safavi, Email: moein.safavi@gmail.com.

Mehrzad Mehdizadeh, Email: mehdizad@sina.tums.ac.ir.

References

- 1.Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy. A newly recognized benign clinicopathological entity. Arch Pathol. 1969;87(1):63–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaltman JM, Best SP, McClure SA. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy Rosai–Dorfman disease: a unique case presentation. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology, oral radiology, and endodontics. Oral Maxillofacial Surg. 2011;112(6):e124–e126. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andriko JA, Morrison A, Colegial CH, Davis BJ, Jones RV. Rosai–Dorfman disease isolated to the central nervous system: a report of 11 cases. Modern Pathol. 2001;14(3):172–8. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sandoval-Sus JD, Sandoval-Leon AC, Chapman JR, Velazquez-Vega J, Borja MJ, Rosenberg S, et al. Rosai–Dorfman disease of the central nervous system: report of 6 cases and review of the literature. Medicine. 2014;93(3):165–75. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000000030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Safavi M, Panjavi B, Pak N. Rosai–Dorfman disease arising in patella. Arch Iran Med. 2019;22(12):731–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shulman S, Katzenstein H, Abramowsky C, Broecker J, Wulkan M, Shehata B. Unusual presentation of Rosai–Dorfman disease (RDD) in the bone in adolescents. Fetal Pediatr Pathol. 2011;30(6):442–7. doi: 10.3109/15513815.2011.618873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nawroz IM, Wilson-Storey D. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai–Dorfman disease). I. Histopathology. 1989;14:91–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1989.tb02118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ajise OE, Stahl-Herz J, Goozner B, Cassai N, McRae G, Wieczorek R. Extranodal Rosai–Dorfman disease arising in the right atrium: a case report with literature review. Int J Surg Pathol. 2011;19(5):637–42. doi: 10.1177/1066896911409577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang HY, Yang CL, Chen WJ. Rosai–Dorfman disease with primary cutaneous manifestations—a case report. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1998;27(4):589–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merola JF, Pulitzer M, Rosenman K, Brownell I. Cutaneous Rosai–Dorfman disease. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14(5):8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dahlgren M, Smetherman DH, Wang J, Corsetti RL. Rosai–Dorfman disease of the breast and parotid gland. J Louisiana State Med Soc. 2008;160(1):35–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kruse AL, Gengler C, Gratz KW, Obwegeser JA. Extranodal manifestation of Rosai–Dorfman disease without involvement of lymph nodes. J Craniofac Surg. 2010;21(6):1733–6. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181f403ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Molina-Garrido MJ, Guillen-Ponce C. Extranodal Rosai–Dorfman disease with cutaneous and periodontal involvement: a rare presentation. Case Rep Oncol. 2011;4(1):96–100. doi: 10.1159/000324760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brau RH, Sosa IJ, Marcial-Seoane MA. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai–Dorfman disease) and extranodal involvement of the orbit. Puerto Rico Health Sci J. 1995;14(2):145–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chhabra S, Agarwal R, Garg S, Singh H, Singh S. Rosai–Dorfman disease: a case report with extranodal thyroid involvement. Diagn Cytopathol. 2012;40(5):447–9. doi: 10.1002/dc.21737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.SC C. Rosai–Dorfman disease report of a case presenting as a midline thyroid mass. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:197–8. doi: 10.5858/2003-127-e197-RD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.da Silva BB, Lopes-Costa PV, Pires CG, Moura CS, Borges RS, da Silva RG. Rosai–Dorfman disease of the breast mimicking cancer. Pathol Res Pract. 2007;203(10):741–4. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Warpe BM, More SV. Rosai–Dorfman disease: a rare clinico-pathological presentation. Australas Med J. 2014;7(2):68–72. doi: 10.4066/amj.2014.1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ilie M, Guevara N, Castillo L, Hofman P. Polypoid intranasal mass caused by Rosai–Dorfman disease: a diagnostic pitfall. J Laryngol Otol. 2010;124(3):345–8. doi: 10.1017/s0022215109990818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gregor RT, Ninnin D. Rosai–Dorfman disease of the paranasal sinuses. J Laryngol Otol. 1994;108(2):152–5. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100126143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pinto DCG, de Aguiar Vidigal T, de Castro B, dos Santos BH, de Sousa NJA. Rosai–Dorfman disease in the differential diagnosis of cervical lymphadenopathy. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;74(4):632–5. doi: 10.1016/s1808-8694(15)30616-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.El-Banhawy OA, Farahat HG, El-Desoky I. Facial asymmetry with nasal and orbital involvement in a case of sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai–Dorfman disease) Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;69(8):1141–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2005.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hur K, Liu C, Koempel JA. Paranasal Rosai–Dorfman disease with osseous destruction. Case Rep Otolaryngol. 2017;2017:1453097. doi: 10.1155/2017/1453097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maeda Y, Ichimura K. Rosai–Dorfman disease revealed in the upper airway: a case report and review of the literature. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2004;31(3):279–82. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2004.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Belcadhi M, Bellakhdhar M, Sriha B, Bouzouita K. Rosai–Dorfman disease of the nasal cavities: A CO(2) laser excision. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2010;24(1):91–3. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2010.24.3387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gaddey HL, Riegel AM. Unexplained lymphadenopathy: evaluation and differential diagnosis. Am Family Phys. 2016;94(11):896–903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ribeiro BN, Marchiori E. Rosai–Dorfman disease affecting the nasal cavities and paranasal sinuses. Radiol Bras. 2016;49(4):275–6. doi: 10.1590/0100-3984.2015.0167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.La Barge DV, Salzman KL, Harnsberger HR, Ginsberg LE, Hamilton BE, Wiggins RH. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai–Dorfman disease): imaging manifestations in the head and neck. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191(6):W299–306. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruggiero A, Attina G, Maurizi P, Mule A, Tarquini E, Barone G, et al. Rosai–Dorfman disease: two case reports and diagnostic role of fine-needle aspiration cytology. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2006;28(2):103–6. doi: 10.1097/01.mph.0000200686.33291.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi Y, Griffin AC, Zhang PJ, Palmer JN, Gupta P. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai–Dorfman disease): a case report and review of 49 cases with fine needle aspiration cytology. CytoJournal. 2011;8:3. doi: 10.4103/1742-6413.76731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garza-Guajardo R, Garcia-Labastida LE, Rodriguez-Sanchez IP, Gomez-Macias GS, Delgado-Enciso I, Chaparro MM, et al. Cytological diagnosis of Rosai–Dorfman disease: a case report and revision of the literature. Biomed Rep. 2017;6(1):27–31. doi: 10.3892/br.2016.814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Malley DP, Duong A, Barry TS, Chen S, Hibbard MK, Ferry JA, et al. Co-occurrence of Langerhans cell histiocytosis and Rosai–Dorfman disease: possible relationship of two histiocytic disorders in rare cases. Mod Pathol. 2010;23(12):1616–23. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yafeng L, Dan L, Jingtao D, Lei L. Retrospective analysis of treatment strategies for nasal Rosai–Dorfman disease: physiological perspective. Int J Clin Exp Physiol. 2014;1(4):266. doi: 10.4103/2348-8093.149754. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wenig BM, Abbondanzo SL, Childers EL, Kapadia SB, Heffner DR. Extranodal sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai–Dorfman disease) of the head and neck. Hum Pathol. 1993;24(5):483–92. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(93)90160-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goodnight JW, Wang MB, Sercarz JA, Fu YS. Extranodal Rosai–Dorfman disease of the head and neck. Laryngoscope. 1996;106(3 Pt 1):253–6. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199603000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ku PK, Tong MC, Leung CY, Pak MW, van Hasselt CA. Nasal manifestation of extranodal Rosai–Dorfman disease—diagnosis and management. J Laryngol Otol. 1999;113(3):275–80. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100143786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gupta L, Batra K, Motwani G. A rare case of Rosai–Dorfman disease of the paranasal sinuses. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;57(4):352–4. doi: 10.1007/bf02907713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khan AA, Siraj F, Rai D, Aggarwal S. Rosai–Dorfman disease of the paranasal sinuses and orbit. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2011;4(2):94–6. doi: 10.5144/1658-3876.2011.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ashish G, Chandrashekharan R, Parmar H. Rare case of Rosai–Dorfman disease involving paranasal sinuses in paediatric patient: a case report. Egypt J Ear Nose Throat Allied Sci. 2016;17(1):43–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejenta.2015.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]