Abstract

This article reviews odontogenic and developmental oral lesions encountered in the gnathic region of pediatric patients. The process of odontogenesis is discussed as it is essential to understanding the pathogenesis of odontogenic tumors. The clinical presentation, microscopic features, and prognosis are addressed for odontogenic lesions in the neonate (dental lamina cysts/gingival cysts of the newborn, congenital (granular cell) epulis of the newborn, melanotic neuroectodermal tumor, choristoma/heterotopia, cysts of foregut origin), lesions associated with unerupted/erupting teeth (hyperplastic dental follicle, eruption cyst, dentigerous cyst, odontogenic keratocyst/keratocystic odonogenic tumor, buccal bifurcation cyst/inflammatory collateral cyst) and pediatric odontogenic hamartomas and tumors (odontoma, ameloblastic fibroma, ameloblastoma, adenomatoid odontogenic tumor, primordial odontogenic tumor). Pediatric odontogenic and developmental oral lesions range from common to rare, but familiarity with these entities is essential due to the varying management implications of these diagnoses.

Keywords: Odontogenic tumor, Odontogenesis, Pediatric, Neural crest, Hamartoma, Ameloblastic fibroma, Primordial odontogenic tumor, Gnathic, Odontoma, Odontogenic cyst

Introduction

Pediatric oral pathology encompasses a diverse group of entities that range from exceedingly common to the point of being considered a normal anatomic variant to exquisitely rare. In general, looking at oral pathology as a whole, 8.2% of oral biopsies are received from patients less than 16 years of age [1], but this will vary between diagnostic service departments.

In this review, we have primarily focused on oral lesions that occur most usually in a pediatric population and are developmental in origin. Many lesions within the mouth occur over a wide age range from children to adults, and covering these would render this review voluminous, thus such lesions have been omitted, unless there are specific pediatric features to consider. In relation to many of the odontogenic lesions that arise in the jaws, an understanding of the process of normal odontogenesis is helpful in distinguishing pathology from the process of normal development. In the context of this collection of papers, this has relevance to the function of neural crest derived cells in the development of teeth and other facial structures, and so, we start with a brief overview of odontogenesis.

Overview of Odontogenesis

The development of teeth is a complex reciprocally interactive process, involving cells from the ectoderm of the first branchial arch and neural crest derived dental mesenchyme. Much of the molecular detail of these interactions has been described in recent years. This is complex, and beyond the scope of this review. For an overview of the molecular aspects of tooth development, the reader is directed to a number of recent comprehensive reviews [2, 3].

The first morphological features of tooth development relate to the development of the primary epithelial band (PEB) in the 5th week of intrauterine life (IUL) (Fig. 1a). These thickenings of the primitive oral epithelium are roughly horseshoe shaped, outlining the shape of the future dental arches of the jaws. Localized thickenings, known as dental placodes, are associated with the site of future teeth, and as the PEB develops, it separates into the vestibule lamina (which gives rise to the vestibular sulcus) and the dental lamina (Week 6–7 IUL; Fig. 1b). The development of the dental lamina is associated with condensation in the associated mesenchyme (Fig. 1c). Proliferation within the dental lamina continues, leading to the formation of the enamel organ, which proceeds morphologically via the bud, cap and bell stages prior to the initiation of dental hard tissue formation (Fig. 1d).

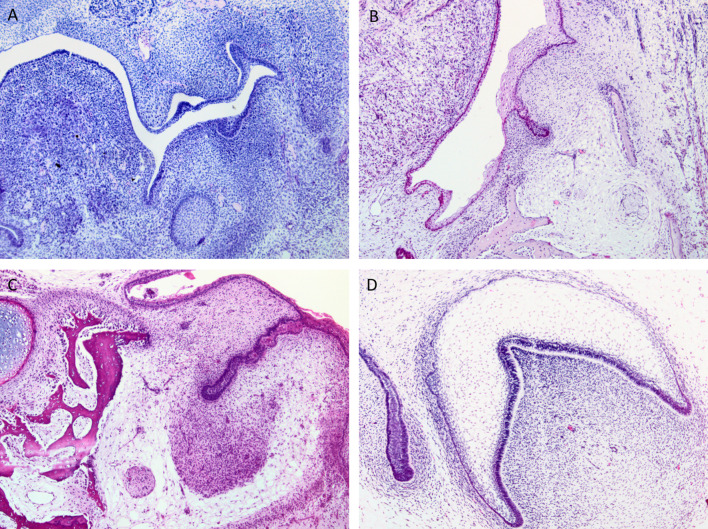

Fig. 1.

Histological images of the stages of tooth development, starting with the primary epithelial band (a), the early dental lamina (b), Bud stage of tooth development with associated condensation of ectomesenchyme (c) and Bell-stage of tooth development, demonstrating the inner enamel epithelium and dental papilla, prior to the commencement of hard tissue formation (d)

In parallel with the development of the epithelial components of the tooth development apparatus, the associated mesenchyme, which has originated from the neural crest, separates in to two main subsites: the dental papilla, which becomes enclosed by the developing cap/bell stage of enamel organ formation and the dental follicle which surrounds the entire enamel organ. As morpho-differentiation proceeds, this is supplemented by cells from a mesoderm origin, principally providing the blood supply [4].

The commencement of dental hard tissue formation is a reciprocal inductive process with the initial formation of the enamel knot in the inner enamel epithelium. This acts as a signaling center in tooth development, driving the differentiation of the peripheral dental papilla cells into odontoblasts, immediately adjacent to the inner enamel epithelium. This differentiation and secretion of the initial dentine matrix results in the final maturation of the inner enamel epithelium into secretory ameloblasts and the initiation of enamel formation. Crown formation continues with the leading edge of the enamel organ forming the cervical loop. This will eventually continue the development of the tooth root as the root sheath of Hertwig. This structure contributes to the development of root dentin, cementum and the periodontal ligament [5, 6].

The function of the dental lamina and dental mesenchyme is controlled in a spatial and temporal fashion by the activation of signaling pathways including wnt, FGF, and shh [2]. This is coordinated by a number of transcription factors, the best described of which is pitx2, but many others are crucial, including the function of the Homeobox-containing transcription factors [7], such as Msx-1. A number of stem cell markers, including SOX2, are key in the functioning of the dental lamina. Constitutive activation of the wnt signaling in mice results in the development of supernumerary teeth and odontome-like lesions, associated with an increase in SOX2 expression in the expanded dental lamina [8]. With further investigation, it will be possible to map these molecular pathways to the developmental abnormalities we see in children and young adults [3].

Once the process of odontogenesis is complete, a number of remnants of the tooth forming tissue remain. The dental lamina can undergo involution from the bell stage of tooth development onwards, resulting in the formation of dental lamina rests (DLR) in the tissues surrounding the developing teeth (Fig. 2). These may persist throughout development into adult life and are often identified in the pericoronal tissues, either within the dental follicle, or associated with pathologies, such as dentigerous cysts. The frequency of these DLRs reduces with age [9], but there is compelling evidence that they are a source of epithelium for a number of odontogenic hamartomas and neoplasms. Other parts of the tooth forming apparatus also fragment, including the root sheath of Hertwig, which remains as the cell rests of Malassez, often found within the periodontal ligament.

Fig. 2.

The varied appearance of epithelial remnants of the tooth forming apparatus, which may be found throughout the soft tissues of the mandibular or maxillary alveolus as Dental Lamina Rests (DLRs) or cell rests of Mallasez in the periodontal ligament

Lesions in the Neonate and Young Children

Odontogenic Lesions in the Neonate

Dental Lamina Cysts/Gingival Cysts of the Newborn

Small cysts of dental lamina origin are very common in neonates, having been reported in 25–53% of newborns [10]. The terminology used is confusing and inconsistent, with the terms Bohn nodules and Epstein pearls used in various descriptions [11]. The use of both of these terms is discouraged, as in this context, neither term is being used in keeping with the original description. Bohn nodules may present on the alveolus, but the term was originally used for lesions on the palate and the lingual aspect of the alveolus, probably salivary in origin. Epstein pearls were originally described in the mid-palate raphe, most likely as remnants from the fusion of the palatal shelves.

Clinical Presentation

These lesions present as superficial small white round lesions within the alveolar mucosa (Fig. 3a). These do not require treatment as with time, due to their superficial situation, they rupture due to trauma, and thus disappear. The main clinical issue is misdiagnosis of the oral lesions of pseudomembranous candidiasis, leading to inappropriate use of antifungal medication.

Fig. 3.

(a) Clinical appearance of dental lamina cysts in a neonate, evident on the side of the maxillary alveolus. (b) Histological features of dental lamina cysts demonstrating a thin epithelial lining, a lumen filled with keratin and a communication with the surface. (c) Gross image of a congenital (granular cell) epulis demonstrating a tan-white, fleshy homogeneous cut tissue surface. (d) Histologic appearance of sheets of a congenital (granular cell) epulis demonstrating submucosal polygonal cells with a granular, eosinophilic cytoplasm

Histological Features

These lesions are exceedingly rarely biopsied, but have been described as small, superficial cysts lined by keratinized stratified squamous epithelium, microscopically somewhat reminiscent of an epidermoid cyst, filled with keratin debris, and which may have a connection to the surface epithelium (Fig. 3b).

Congenital (Granular Cell) Epulis of the Newborn

This benign, pedunculated swelling in the anterior part of the mouth is present at birth (or occasionally diagnosed in utero) and is more common in females. Due to its typical anatomic location, it may interfere with feeding and respiration, and most are removed during the first weeks of life. Once removed, the lesion does not recur even if incompletely excised [12]. The histogenesis is disputed, but theorized to be derived from primitive neural mesenchymal cells of neural crest origin or myopericyctic cells [13].

Clinical Presentation

The lesion most commonly arises on the anterior maxillary alveolar ridges of neonates (Fig. 3c), with a strong female (8:1) and maxillary predilection (3:1), and in 10% of cases multiple lesions are reported. Lesions have been reported on the mandible and other associated sites [12–14]. Lesions of considerable size, which may compromise the airway have been described [11].

Histological Features

The overlying epithelium may exhibit atrophy with focal ulceration. These are pedunculated mucosal nodules, largely consisting of sheets of polygonal cells with a granular, eosinophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 3d), distinct cell borders, centrally placed nuclei and inconspicuous nucleoli. Odontogenic rests may be seen. A spindle cell variant has been described [14]. The supporting stroma has prominent vasculature and the surface epithelium is attenuated, in contrast to that often seen in granular cell tumors. Immunohistochemically the cells are negative for most markers. The lesions are negative for S-100 and without CD68 positive hyaline globules, distinguishing them from granular cell tumors common in the oral tongue in adults [15]. Alveolar soft part sarcoma can have a granular appearance but would be positive for periodic acid-Schiff with diastase-resistance, presenting later in childhood.

Melanotic Neuroectodermal Tumor

Melanotic neuroectodermal tumor of infancy (MNETI) is a rare, aggressive tumor seen in younger pediatric patients that usually is benign, but local recurrence is frequent and metastasis may be seen [16].

Clinical Presentation

Clinically, MNETI presents as an asymptomatic firm, expansile, mass and if superficial a blue/black hue may be noted. If intraosseous, this would correspond to a radiolucent lesion with cortical expansion. There is a slight male sex predilection with a median age at diagnosis of approximately 4.5 months (mean age of 15 months). Approximately 90% of lesions present in the craniofacial region with about 80% in the gnathic region and the maxilla is far more common than the mandible (13:3) [16–18]. Distant sites are reported, however, in the head and neck, the skull, orbit, and primary intracranial sites such as dura and brain may be involved [16, 17]. The lesions can significantly vary in size from 0.5 to 20.5 cm with an average size of 3.85 cm [17]. Urinary vanillylmandelic acid excretion may be detected given their probable neural crest derivation.

Histological Features

Grossly, MNETI is firm, lobulated, and pigment may be appreciated on sectioning [19]. On small biopsies, a variety of “small round blue cell tumors” enter the differential diagnoses. MNETI are biphasic (Fig. 4a) neoplasms characterized by larger more peripheral epitheloid cells containing melanin and smaller neurogenic cells exhibit “salt and pepper” chromatin [16]. Both cell populations are positive for neuron specific enolase, the epitheloid cells are positive for cytokeratins, HMB-45, the smaller cells may stain for GFAP, synaptophysin, and S-100 [16, 19]. The mitotic count is usually low (ranging from 0 to 2 per 10 high power fields), higher mitotic indices and CD99 staining has been suggested to correlate with recurrence [18]. A rare MNETI was found to harbor a BRAF V600E mutation, a finding that requires additional investigation [20].

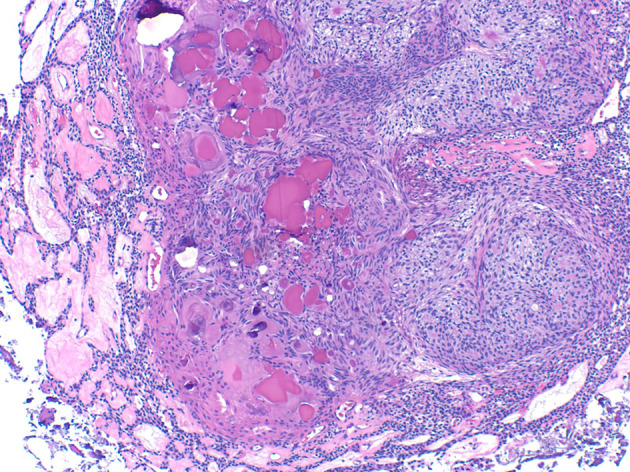

Fig. 4.

(a) Histologic appearance of a melanotic neuroectodermal tumor of infancy, tumor islands with peripheral epitheloid cells containing melanin and smaller neurogenic cells exhibit “salt and pepper” chromatin are seen. (b) Cyst of foregut origin of the tongue that demonstrated squamous, respiratory, and gastric epithelial lining (pictured)

Choristoma/Heterotopia

A choristoma is a tumour-like growth of normal tissues in an abnormal location. The term heterotopia somewhat overlaps with this, but lacks the implication of the development of a defined lesion within this tissue. Choristomas may comprise a number of different tissue types, including salivary gland (either within the bone of the jaws or in gingival tissues), cartilaginous or osseous lesions (most in the tongue) [21], glial tissue (more common in the sinonasal tract) [22], or thyroid tissue. Choristomas will be discussed in additional detail in the section on Pluripotency in the Head and Neck within this special edition on head and neck pediatric pathology.

Cysts of Foregut Origin

A number of developmental cystic lesions also fall into this category, many of which occur in the tongue and may be lined by respiratory epithelium [23], gastric epithelium, intestinal epithelium [24]. Oral cysts containing gastric or intestinal mucosa due to an unusual embryological accident or heterotopia, or any combination of these [25, 26]. A plethora of terms have been used in the literature to describe these lesions, including heterotopic oral gastrointestinal cyst and lingual foregut cysts. It is possible that these cysts, with variable histological features, all arise from epithelium of foregut origin that is entrapped in the tongue during development.

Clinical Presentation

These most often present as a cystic lesion in the anterior tongue of floor of mouth of infants or young children.

Histological Features

The lining of the cyst is most commonly of gastric epithelium type, although in may be admixed with other types, such as stratified squamous or ciliated columnar epithelium (Fig. 4b). Excision is curative.

Lesions Associated With Unerupted/Erupting Teeth

Hyperplastic Dental Follicle

A dental follicle normally surrounds a developing tooth prior to eruption, but it may become enlarged with fluid accumulation between the epithelium and the crown or inflamed. Hyperplastic dental follicles represent 5.5%–6.3% of all pediatric lesions submitted for biopsy and 18.9% of non-neoplastic oral pathologies in pediatric patients, more common in the 10–19 year age range with a mean age of approximately 13 years [1, 27].

Clinical Presentation

Clinically, an asymptomatic unilocular radiolucency less than 4 mm surrounding the crown of an impacted tooth is seen.

Histological Features

A thin layer of reduced enamel epithelium, which is columnar and low cuboidal basilar cells, line the cyst (Fig. 5a). As the epithelial connective tissue interface is flat, the cystic lining may strip away from the connective tissue wall.

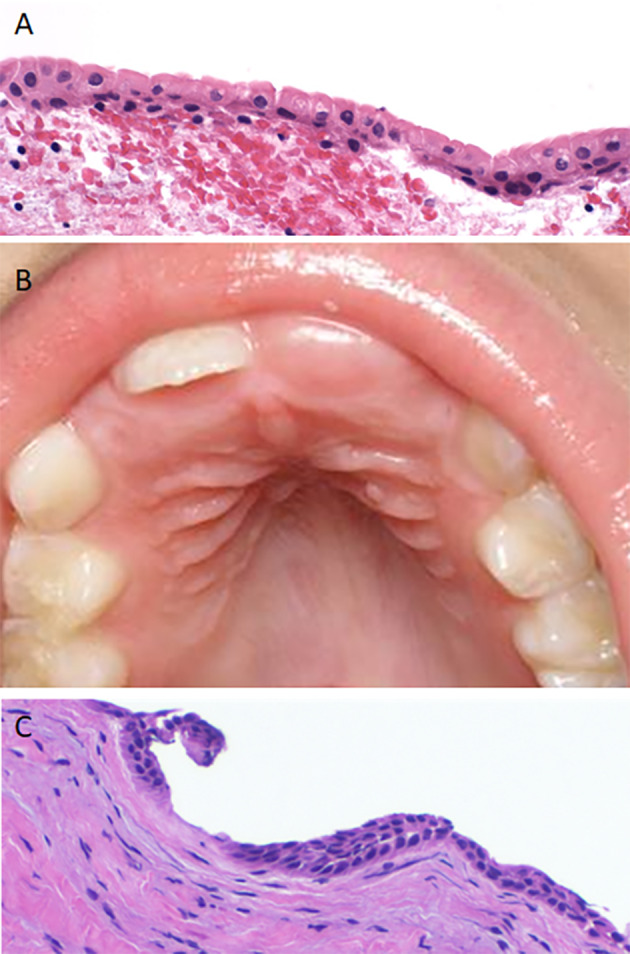

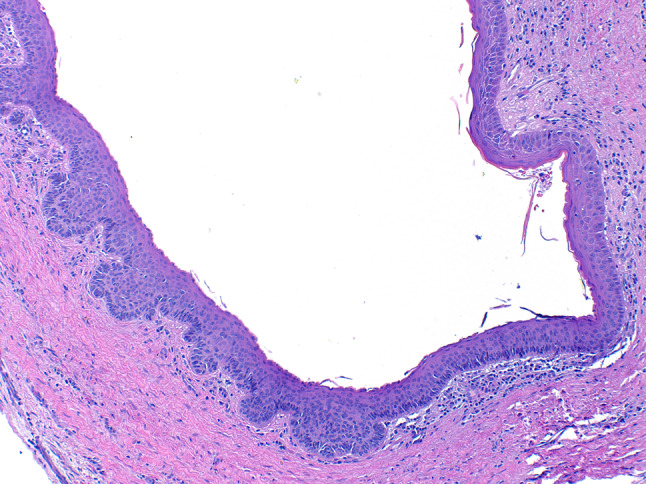

Fig. 5.

(a) A hyperplastic dental follicle demonstrating a thin epithelial lining with luminal columnar cells and low cuboidal basilar cells. (b) Eruption cyst presenting as a mucosal colored domed shaped swelling over the erupting central incisor. (c) Histologically, the eruption cyst lining is thin and bilayed resembling follicular lining

Eruption Cyst

Eruption cyst is considered to be the soft tissue counterpart of a dentigerous cyst, sometimes is referred to as an eruption hematoma.

Clinical Presentation

Eruption cysts are pediatric developmental cysts (mean age 5.4 years) that present clinically as a translucent to bluish, dome-shaped swelling over the permanent or less commonly the primary erupting tooth. The maxilla is most commonly affected and the central incisors or first molars are commonly involved (Fig. 5b) [28–30].

Histological Features

These lesions are more commonly encountered clinically and rarely biopsied. Beneath the surface squamous epithelium histologically, a thin layer of connective tissue and the cystic lining of the follicle is seen (Fig. 5c). The lesions most often spontaneously resolve with tooth eruption, but when discomfort is noted, excision may be elected [28].

Dentigerous Cyst

Dentigerous cysts are developmental cysts found around the crown of primary or permanent teeth.

Clinical Presentation

The most common location is surrounding unerupted or impacted mandibular third molars (77%), followed by the maxillary canine (11%). They present as well-defined unilocular radiolucent lesions connecting to the tooth at the cemento-enamel junction, but they may also be seen in association with supernumerary teeth or odontomas [31, 32].

Histological Features

Microscopically, they are lined by nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium with a surrounding connective tissue wall (Fig. 6a). Ciliated cells, mucous cells, clear cells, and sebaceous metaplasia may be seen. In one series 2.38% of dentigerous cysts were found to have mucous cells and 10.8% have cilia, with mucous cells more common in the mandible and ciliated cells more common in the maxilla [33]. Inflammation, Rushton bodies, and cholesterol clefts with a giant cell reaction may also be present.

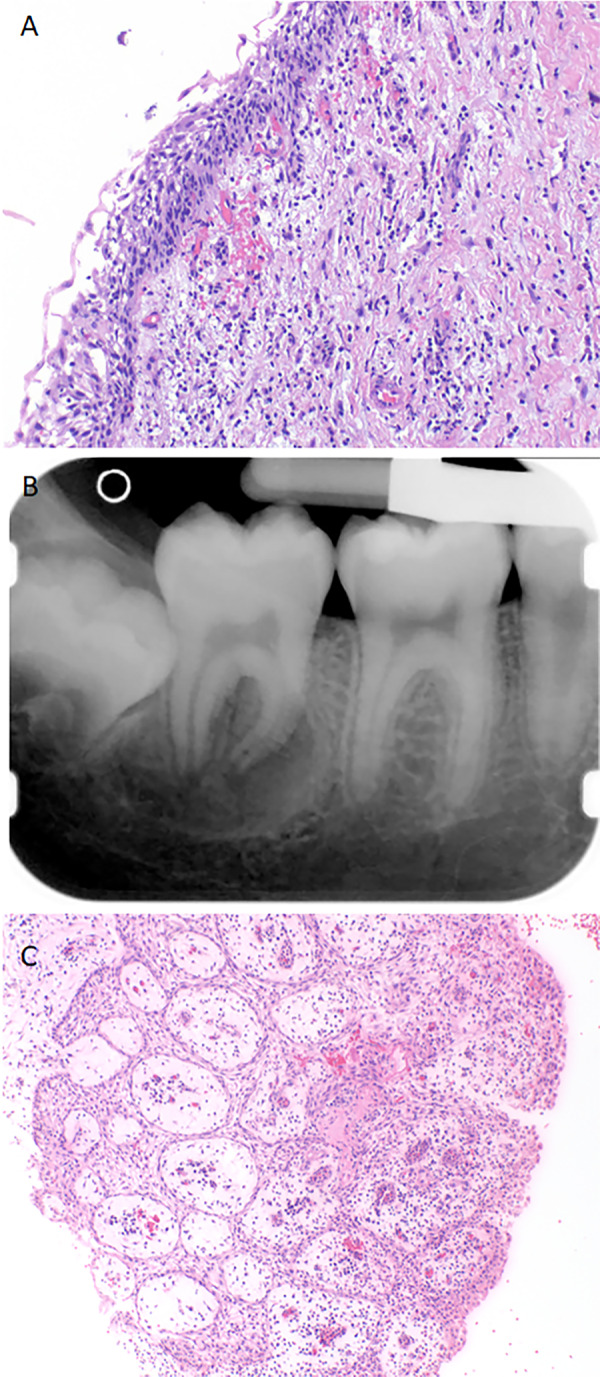

Fig. 6.

(a) An inflamed dentigerous cyst exhibiting a nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelial lining. (b) Periapical radiograph depicting a buccal bifurcation cyst as a well-defined radiolucency involving the furcation of the tooth extending beyond the apices. (c) Histologically, an inflamed buccal bifurcation cyst demonstrates non-specific features that overlap with a periapical or radicular cyst, illustrating the need for clinical correlation for an accurate diagnosis

Odontogenic Keratocyst Cyst/Keratocystic Odontogenic Tumor

Odontogenic keratocyst cyst (OKC) /keratocystic odontogenic tumor (KCOT) is a neoplastic developmental cyst.

Clinical Presentation

OKC/KCOT have a slight male predilection. OKC/KCOT present over a wide age range, although they are uncommon in patients younger than the age of 10. There is a sharp increase in the second decade of life and the peak incidence is in the second and third decades of life [34, 35]. About 75% of cysts are mandibular, being particularly common (60%) in the molar/ramus area [34, 35]. In one series, about 50% of cases were associated with an impacted tooth, thus clinically they can mimic dentigerous cysts [36]. There is a propensity for anterior posterior growth. Radiographically, the lesions are often well-defined unilocular radiolucencies, but lesions may be multilocular, more commonly larger lesions. [36].

Histological Features

Histologically, the lesion is cystic lined by a uniform thickness of epithelium that is approximately 6–8 cells thick with a palisaded columnar or cuboidal hyperchromatic basal cell layer, and a wavy parakeratinized surface [35]. The epithelial lining has a tendency to separate from the connective tissue [35]. Scattered mitotic figures may be seen in the epithelial lining [35]. KCOT/OKC may exhibit basilar budding (Fig. 7), satellite cysts, and epithelial islands in the collagenous stroma. These are features linked with an increased risk of recurrence as well as Basal Cell Nevus Syndrome (BCNS). Heavy inflammation may obscure the classic histologic features.

Fig. 7.

Histologic image of an odontogenic keratocyst/keratocystic odontogenic tumor demonstrating classic features of a uniform epithelial thickness, hyperchromatic basal cell layer, and wavy surface parakeratin transitioning to prominent basilar budding

The OKC/KCOT can be distinguished from the orthokeratinized odontogenic cyst (OOC) as OOC has orthokeratin and lacks basal cell palisading. This is an important distinction as the OOC does not have the same recurrence potential [37].

The pathogenesis of both sporadic and syndromic OKC/KCOT is due to the constitutive activation of hedgehog signaling pathway, which is most commonly due to mutation of the patched gene (PTCH1), a tumor suppressor gene [38, 39]. As one of the major diagnostic criteria for BCNS is the diagnosis of an KCOT/OKC in a patient less than 20 years of age, young pediatric patients diagnosed with KCOT/OKC, especially those with multiple lesions should be evaluated for BCNS [40]. Other manifestations of BCNS may include basal cell carcinomas prior to the age of 20, palmar/plantar pitting, desmoplastic medulloblastoma, ovarian/cardiac fibromas, lymphomesenteric cysts, ocular abnormalities (i.e. hypertelorism, strabismus, congenital cataracts), radiologic changes (i.e. bifid ribs, calcification of the falx cerebri, vertebral abnormalities, kyphoscoliosis), cleft lip, cleft palate, and macrocephaly [37, 40].

KCOT/OKC have a wide reported rate of recurrence in the literature dependent on duration of follow-up and surgical procedure, more recent recurrent rates are approximately 20% [35]. The treatment of OKC/KCOT includes marsupialization, enucleation (with or without peripheral ostectomy, treatment with Carnoy solution, cryotherapy) or resection.

Buccal Bifurcation Cyst/Inflammatory Collateral Cyst

Buccal bifurcation cyst or inflammatory collateral cyst is a type of inflammatory paradental cyst that results from inflammation in the periodontal pocket.

Clinical Presentation

While the majority of paradental cysts involve partially or fully erupted mandibular third molars (61.4%), the buccal bifurcation cyst, considered to be a subtype of paradental cysts, is a pediatric lesion (mean age 7.5 years). They are most commonly associated with vital first or second mandibular permanent molars (35.9%) occasionally occurring bilaterally [41, 42]. Lesions may be mildly symptomatic to overtly painful, with swelling, expansion, and delayed eruption. The cyst is a well-defined radiolucency buccal to the molar extending from the furcation to the root apices (Fig. 6b), periosteal reaction may be seen (68.2% of cases) and the tooth is tipped, with the roots apices lingual and the cusp tips buccal [41, 42].

Histological Features

As this is an inflammatory cyst, microscopically the features overlap and are indistinguishable from a periapical/radicular cyst without clinical context. The epithelium is stratified squamous epithelium of varying thickness with spongiosis and an admixed brisk acute and chronic inflammatory infiltrate in the connective tissue wall (Fig. 6c) [41]. Buccal bifurcation cysts can be managed with enucleation, allowing for tooth preservation [42].

Pediatric Odontogenic Hamartomas and Tumors

Odontoma

If considered a tumor, rather than a hamartoma, odontomas are the most common odontogenic tumor. One series looking at 2114 pediatric oral biopsies, found odontomas as the most common entity encountered (21.6% of cases) with squamous papillomas next most frequent (19.0%) [27].

Clinical Presentation

Odontomas are most frequently asymptomatic intraosseous lesions diagnosed in the second decade of life, often detected radiographically during investigation of delayed tooth eruption (Fig. 8a) [43]. Less commonly, they may be extraosseous or soft-tissue lesions.

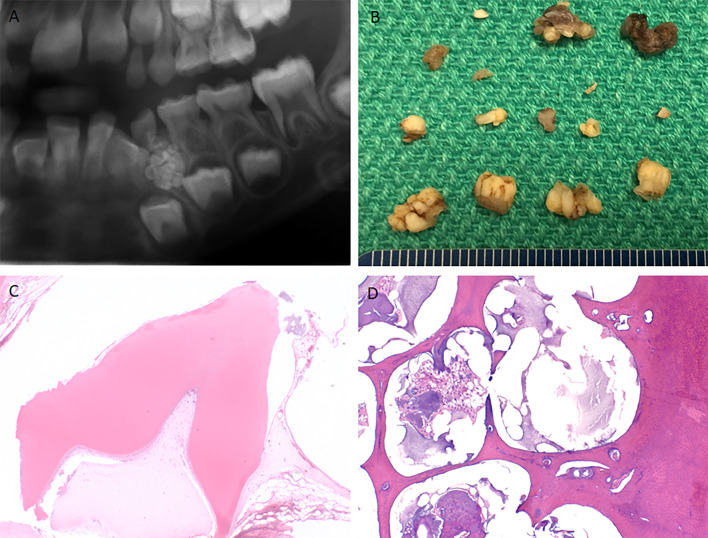

Fig. 8.

(a) Cropped panoramic radiograph of a compound odontoma demonstrating numerous small tooth-like structures surrounded by a thin radiolucent rim. (b) Gross examination of a compound odontoma reveals multiple small malformed tooth-like structures. (c) Compound odontoma histologically demonstrates tooth form appearance, most of the enamel has been lost during decalcification. (d) Complex odontoma demonstrates aberrant arrangement of dentin, enamel, and soft tissue

Histological Features

Odontomas can be divided into compound odontomas and complex odontomas. Compound odontomas are slightly more common, located in the anterior with a maxillary predilection comprised of radiographically diagnostic, small, tooth-like structures enclosed in a fibrous capsule representing 63.2% of odontomas. Complex odontomas are more common in the posterior mandible, microscopically consisting of a disorganized conglomerate of dental hard tissues cementum, dentin, and enamel (some of which is loss in the process of decalcification), as well as pulpal tissue (Fig. 8b–d) [44]. A number of syndromes are associated with odontomas [44]. Ghost cells may be seen in odontomas but there is no clinical significance to this histologic finding [43]. Management is excision.

Ameloblastic Fibroma

Ameloblastic fibromas (AF) are relatively uncommon mixed tumors with both an epithelial and a mesenchymal component.

Clinical Presentation

A review of the literature by Buchner and Vered found that AF present with a mean age of 14.9 years (median age 11) with a posterior (82%) and mandibular predilection (77%) with most lesions in the anterior located in the maxilla [45]. Clinically, tumors ranged from 0.7 cm to 14.0 cm with a mean size of 4.2 cm. These present with painless expansion (46%) or less commonly, painful expansion (8.5%). Radiographically they appear as a well-defined/sclerotic (94%), smaller unilocular (56%) or larger lesions multilocular (44%) radiolucencies (Fig. 9a) [45].

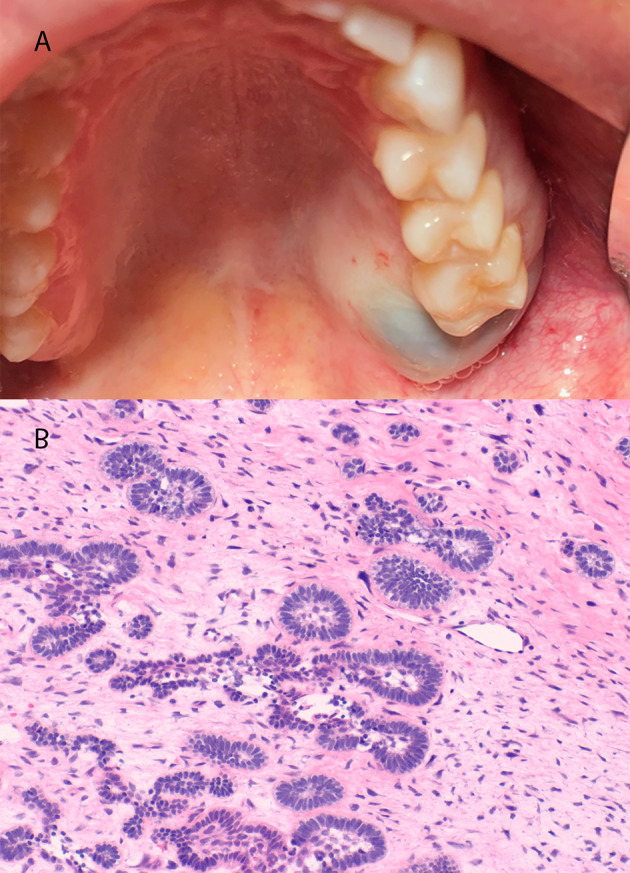

Fig. 9.

(a) Clinical appearance of ameloblastic fibroma in the posterior maxilla demonstrating expansion. (b) Ameloblastic fibroma exhibiting cellular myxoid ectomesenchymal stroma containing scattered ameloblastic islands with central stellate reticulum

Histological Features

The histopathologic features include odontogenic epithelial nests arranged in strands and cords in a cellular ectomesenchymal stroma that resembles dental papilla. The strands and cords are often composed of cuboidal epithelium with the islands exhibiting columnar ameloblastic epithelium with central stellate reticulum (Fig. 9b). In the Buchner and Vered series of 162 AF, 16.3% of patients experienced recurrence after primary excision and 6.4% of cases reported transformation to ameloblastic fibrosarcoma [45].

In the most recent World Health Organization Classification of Head and Neck Tumors [46], ameloblastic fibro-odontomas, lesions with features of both odontoma and ameloblastic fibroma, were eliminated as a distinct entity, with the justification that, “… it is not possible to distinguish between AFs (true neoplasms) and early-stage odontomas before they differentiate and mature [45, 47]. However, rare AFs show formation of dental hard tissues and reach an exceptional size. These lesions have been referred to as ameloblastic fibrodentinomas or ameloblastic fibro-odontomas [45], but are most likely developing odontomas.” BRAF V600E mutation, a common driver mutation found in mandibular ameloblastomas, has been found via PCR in ameloblastic fibromas as well as the lesion formerly classified as ameloblastic fibro-odontoma or fibro-dentinomas [48, 49], a compelling argument that at least a subset of these lesions are better considered to be benign neoplasms rather than hamartomas. The frequency of BRAF V600E mutation ranges across studies from 40% to 100% [49, 50]. Another study found 5 of 7 ameloblastic fibrosarcomas to have BRAF V600E mutation, one with a NRAS mutation, and one being wild type [51].

Ameloblastoma

Ameloblastoma is the most common odontogenic neoplasm in children and adolescents, in some series, accounting for over 50% of neoplasms, particularly those in an African population [52, 53].

Clinical Presentation

An overall review of pediatric ameloblastoma indicates a slight male preponderance and an age range from 4 to 20 years. Most of these lesions present in the second decade and they are much more common in the mandible (Fig. 10) (>95% in some series) than the maxilla. Unicystic ameloblastomas are commonly associated with impacted teeth (52–86%) and the clinical differential diagnosis includes dentigerous cyst [54].

Fig. 10.

Panoramic radiograph of an ameloblastoma (histologically conventional, solid/multicystic type) in a 7-year-old male patient. There is a well define, largely corticated unilocular radiolucency with displacement of the bicuspid crowns and resorption of the roots of the primary molar teeth

Histological Features

The conventional solid, multicystic ameloblastoma exhibits islands and strands of epithelium resembling stellate reticulum surrounded by cuboidal or columnar cells with reverse polarity (resemblimg preameloblasts) whereas a unicystic ameloblastoma exhibits a large cystic cavity lined focally or rarely entirely by ameloblastomatous epithelium [54]. In general, the reported proportion of unicystic ameloblastoma is much higher in the pediatric population varying from 39% to 81% [52, 53] but the usual caveat in relation to this stands: it is not always possible to ascertain that the whole specimen has been examined histologically. The range of conventional histologic variants in pediatric ameloblastoma are very similar to those in an adult population, with follicular and plexiform variants commonly reported. As with adult ameloblastoma, the risk of recurrence is related to treatment modality and is also related to the size of the initial lesion and the presence of extensions beyond the bony confines of the jaws [55].

Adenomatoid Odontogenic Tumor

Clinical Presentation

Adenomatoid odontogenic tumor (AOT) presents most commonly in females (66.4%) in the maxilla (64.3%) as a central (97.7%) pericoronal lesion (70.9%) with a peak incidence in the second decade of life [56].

Histological Features

Microscopically, AOT are encapsulated tumors that exhibit a constellation of specific and distinctive histologic features (Fig. 10), including a nodular pattern at low pattern with spindle or cuboidal cells forming a rosette-like configuration with little connective tissue. Duct-like structures may be seen imparting a cribriform pattern. Amyloid material may be present, at times forming concentric calcifications reminiscent of the Liesegang rings seen in calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumor. AOTs have a fibrous capsule that surrounds the periphery of the tumor [57]. Multiple AOTs can be seen in Schimmelpenning syndrome, caused by HRAS or KRAS mutations with somatic mosaicism. KRAS mutations have been reported in AOTs. One series of AOTs reported 7 of 9 to have KRAS mutations, including a sample from a patient with Schimmelpenning syndrome [58]. A larger series, demonstrated 27/38 (71%) of AOTs with KRAS codon 12 mutations, supporting its designation as a neoplasm, rather than a hamartoma, in spite of indolent clinical behavior [59] (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11.

Adenomatoid odontogenic tumor histology demonstrating duct-like structures, whorls, amyloid, and calcifications

Primordial Odontogenic Tumor

Primordial odontogenic tumor (POT) was included in the 2017 WHO Classification of Head and Neck Tumours [60] despite only 7 cases having been included in the published literature at the time. To date, only 16 cases have been reported. The designation of POT as a tumor, and its exact nature, has also raised debate as some authors have questioned whether it may it represent a stage of a developing ameloblastic fibroma and whether it is truly an embryonal tumor [61].

Clinical Presentation

POT occur most commonly as large (mean 4.1 cm), asymptomatic, expansile radiolucent lesions (Fig. 12a) in pediatric patients (mean age 11.6) in the posterior mandible (87.5%, mandible:maxilla, 6:1). They occur most commonly in the third molar area in close proximity to a developing tooth, often displacing an impacted tooth [62, 63] .

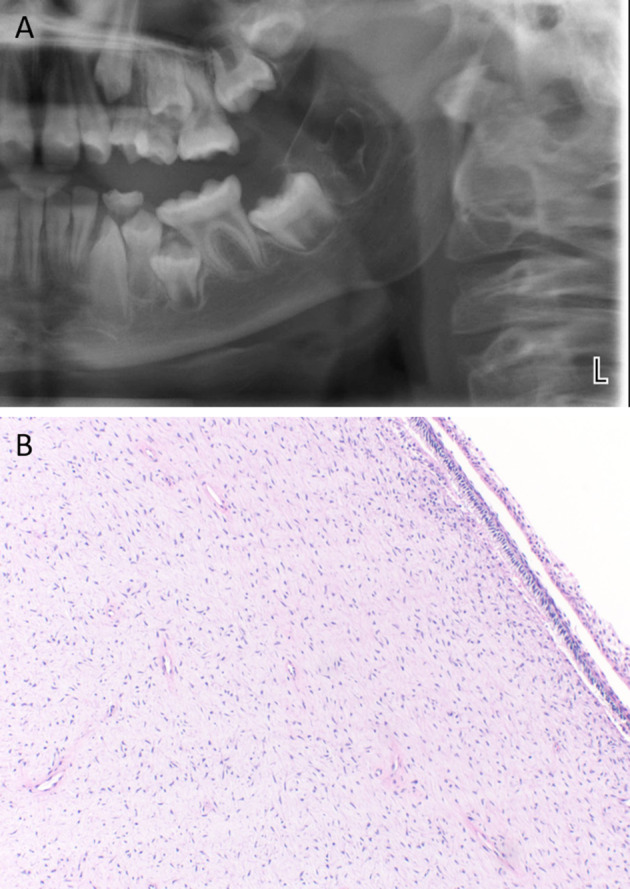

Fig. 12.

Primordial odontogenic tumor (a) Cropped panoramic radiograph demonstrating a well-defined expansile radiolucency in the third molar area (b) Loose, myxoid connective tissue reminiscent of dental papilla surfaced by cuboidal to columnar epithelium

Histological Features

Microscopic hallmarks include central loose fibromyxoid connective tissue, reminiscent of dental papilla, surrounded by cuboidal to columnar epithelium and at least partially encapsulated (Fig. 12b) [63]. Invaginations can lead to focal ameloblastic fibroma-like islands. Four authors reported round, globular calcifications within the stellate reticulum like areas of the tumor, but not odontogenesis [63]. A 151 gene panel revealed no mutations in 6 tested POTs [64]. No recurrences have been reported with most lesions treated with simple excision [63].

Conclusions

Other odontogenic tumors, while more common in adult patients, may present in pediatric patients. There are a myriad of gnathic boney tumors seen in pediatric patients. Some of these entities may be covered in other sections of this head and neck pediatric pathology special edition. This review focuses primarily on selected developmental odontogenic lesions that present in the pediatric population. Thus, this is by no means an exhaustive review of all odontogenic and developmental oral lesions but aims to highlight common and important entities for pathologists to recognize.

Pediatric oral lesions represent a unique and significant subset of oral pathology with markedly varying relative frequency. Some lesions can be particularly challenging due to their relative rarity, combined with the complexity of normal developmental processes. This is particularly true for odontogenic lesions where incomplete clinical and radiographic information is available. Thus, the practicing pathologist should be cognizant of the development of the maxillofacial region to help guide the diagnosis of odontogenic and other developmental lesions in a pediatric population.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the following for their gracious contributions and permission to use clinical/microscopic images. Dr. John Wright, Figs. 3a, b and Dr. Bobby Collins, Fig. 4b.

Author Contributions

EB and KH undertook the initial plan, literature review and wrote the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No external funding was received for this project.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

Neither of the authors have any conflict of interest to declare.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Jones AV, Franklin CD. An analysis of oral and maxillofacial pathology found in children over a 30-year period. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2006;16(1):19–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2006.00683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu T, Klein OD. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of tooth development, homeostasis and repair. Development. 2020;147(2) 10.1242/dev.184754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Cobourne MT, Sharpe PT. Diseases of the tooth: the genetic and molecular basis of inherited anomalies affecting the dentition. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol. 2013;2(2):183–212. doi: 10.1002/wdev.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rothova M, Feng J, Sharpe PT, Peterkova R, Tucker AS. Contribution of mesoderm to the developing dental papilla. Int J Dev Biol. 2011;55(1):59–64. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.103083mr. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guo Y, Guo W, Chen J, Chen G, Tian W, Bai D. Are Hertwig’s epithelial root sheath cells necessary for periodontal formation by dental follicle cells? Arch Oral Biol. 2018;94:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2018.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang J, Feng JQ. Signaling pathways critical for tooth root formation. J Dent Res. 2017;96(11):1221–1228. doi: 10.1177/0022034517717478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thesleff I. Homeobox genes and growth factors in regulation of craniofacial and tooth morphogenesis. Acta Odontol Scand. 1995;53(3):129–134. doi: 10.3109/00016359509005962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Juuri E, Isaksson S, Jussila M, Heikinheimo K, Thesleff I. Expression of the stem cell marker, SOX2, in ameloblastoma and dental epithelium. Eur J Oral Sci. 2013;121(6):509–516. doi: 10.1111/eos.12095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fraser GJ, Hamed SS, Martin KJ, Hunter KD. Shark tooth regeneration reveals common stem cell characters in both human rested lamina and ameloblastoma. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):15956. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-52406-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh RK, Kumar R, Pandey RK, Singh K. Dental lamina cysts in a newborn infant. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012 10.1136/bcr-2012-007061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Bilen B, Alaybeyoglu N, Arslam A, Turkmen E, Alslan S, Celik M. Obstructive congenital gingival granular cell tumour. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;68(12):1567–1571. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tucker MC, Rusnock EJ, Azumi N, Hoy GR, Lack EE. Gingival granular cell tumors of the newborn. An ultrastructural and immunohistochemical study. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1990;114(8):895–898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Damm DD, Cibull ML, Geissler RH, Neville BW, Bowden CM, Lehmann JE. Investigation into the histogenesis of congenital epulis of the newborn. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1993;76(2):205–212. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(93)90206-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Childers EL, Fanburg-Smith JC. Congenital epulis of the newborn: 10 new cases of a rare oral tumor. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2011;15(3):157–161. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaiserling E, Ruck P, Xiao J. Congenital epulis and granular cell tumor: a histologic and immunohistochemical study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1995;80(6):687–697. doi: 10.1016/S1079-2104(05)80253-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kapadia S, Frisman D, Hitchcock C, Ellis G, Popek E. Melanotic neuroectodermal tumor of infancy: clinicopathological, immunohistochemical, and flow cytometric study. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17(6):566–573. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199306000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rachidi S, Sood AJ, Patel KG, Nguyen SA, Hamilton H, Neville BW, et al. Melanotic neuroectodermal tumor of infancy: a systematic review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;73(10):1946–1956. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2015.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barrett AW, Morgan M, Ramsay AD, Farthing PM, Newman L, Speight PM. A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of melanotic neuroectodermal tumor of infancy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;93(6):688–698. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.124000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soles BS, Wilson A, Lucas DR, Heider A. Melanotic neuroectodermal tumor of infancy. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142(11):1358–1363. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2018-0241-RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gomes CC, Diniz MG, de Menezes GH, Castro WH, Gomez RS. BRAFV600E mutation in melanotic neuroectodermal tumor of infancy: toward personalized medicine? Pediatrics. 2015;136(1):e267–e269. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chou LS, Hansen LS, Daniels TE. Choristomas of the oral cavity: a review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1991;72(5):584–593. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(91)90498-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ide F, Shimoyama T, Horie N. Glial choristoma in the oral cavity: histopathologic and immunohistochemical features. J Oral Pathol Med. 1997;26(3):147–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1997.tb00039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peters SM, Park M, Perrino MA, Cohen MD. Lingual cyst with respiratory epithelium: report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2018;126(6):e279–ee84. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2018.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gorlin RJ, Jirasek JE. Oral cysts containing gastric or intestinal mucosa. An unusual embryological accident or heterotopia. Arch Otolaryngol. 1970;91(6):594–597. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1970.00770040824018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knowles KJ, Berkovic J, Gungor A, Al Shaarani M, Lockhart V, Al-Delphi F, et al. Oral foregut duplication cysts: a rare and fascinating congenital lesion. Case report and review of the literature. Am J Otolaryngol. 2017;38(6):724–725. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2016.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manor Y, Buchner A, Peleg M, Taicher S. Lingual cyst with respiratory epithelium: an entity of debatable histogenesis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;57(2):124–127. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(99)90222-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.da Silva Barros CC, da Silva LP, Gonzaga AKG, de Medeiros AMC, de Souza LB, da Silveira EJD. Neoplasms and non-neoplastic pathologies in the oral and maxillofacial regions in children and adolescents of a Brazilian population. Clin Oral Investig. 2019;23(4):1587–1593. doi: 10.1007/s00784-018-2581-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sen-Tunc E, Acikel H, Sonmez IS, Bayrak S, Tuloglu N. Eruption cysts: a series of 66 cases with clinical features. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2017;22(2):e228–ee32. doi: 10.4317/medoral.21499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aguilo L, Cibrian R, Bagan JV, Gandia JL. Eruption cysts: retrospective clinical study of 36 cases. ASDC J Dent Child. 1998;65(2):102–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bodner L, Goldstein J, Sarnat H. Eruption cysts: a clinical report of 24 new cases. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2004;28(2):183–186. doi: 10.17796/jcpd.28.2.038m4861g8547456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang LL, Yang R, Zhang L, Li W, MacDonald-Jankowski D, Poh CF. Dentigerous cyst: a retrospective clinicopathological analysis of 2082 dentigerous cysts in British Columbia. Canada Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;39(9):878–882. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2010.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin HP, Wang YP, Chen HM, Cheng SJ, Sun A, Chiang CP. A clinicopathological study of 338 dentigerous cysts. J Oral Pathol Med. 2013;42(6):462–467. doi: 10.1111/jop.12042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takeda Y, Oikawa Y, Furuya I, Satoh M, Yamamoto H. Mucous and ciliated cell metaplasia in epithelial linings of odontogenic inflammatory and developmental cysts. J Oral Sci. 2005;47(2):77–81. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.47.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brannon RB. The odontogenic keratocyst. A clinicopathologic study of 312 cases. Part I. Clinical features. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1976;42(1):54–72. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(76)90031-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shear M, Speight P. Odontogenic keratocyst. Cysts of the oral and maxillofacial region. 4. Singapore: Blackwell; 2007. pp. 6–58. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Titinchi F, Nortje CJ. Keratocystic odontogenic tumor: a recurrence analysis of clinical and radiographic parameters. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;114(1):136–142. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2012.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bresler SC, Padwa BL, Granter SR. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (Gorlin syndrome) Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10(2):119–124. doi: 10.1007/s12105-016-0706-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li TJ. The odontogenic keratocyst: a cyst, or a cystic neoplasm? J Dent Res. 2011;90(2):133–142. doi: 10.1177/0022034510379016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qu J, Yu F, Hong Y, Guo Y, Sun L, Li X, et al. Underestimated PTCH1 mutation rate in sporadic keratocystic odontogenic tumors. Oral Oncol. 2015;51(1):40–45. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bree AF, Shah MR, Group BC Consensus statement from the first international colloquium on basal cell nevus syndrome (BCNS) Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A(9):2091–2097. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Philipsen HP, Reichart PA, Ogawa I, Suei Y, Takata T. The inflammatory paradental cyst: a critical review of 342 cases from a literature survey, including 17 new cases from the author's files. J Oral Pathol Med. 2004;33(3):147–155. doi: 10.1111/j.0904-2512.2004.00139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pompura JR, Sandor GK, Stoneman DW. The buccal bifurcation cyst: a prospective study of treatment outcomes in 44 sites. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;83(2):215–221. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(97)90008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soluk Tekkesin M, Pehlivan S, Olgac V, Aksakalli N, Alatli C. Clinical and histopathological investigation of odontomas: review of the literature and presentation of 160 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;70(6):1358–1361. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hidalgo-Sanchez O, Leco-Berrocal MI, Martinez-Gonzalez JM. Metaanalysis of the epidemiology and clinical manifestations of odontomas. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008;13(11):E730–E734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buchner A, Vered M. Ameloblastic fibroma: a stage in the development of a hamartomatous odontoma or a true neoplasm? Critical analysis of 162 previously reported cases plus 10 new cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2013;116(5):598–606. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2013.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muller S, Vered M. Ameloblastic fibroma. In: El-Naggar A, Chan J, Grandis J, Takata T, Slootweg P, editors. WHO classification of head and neck tumours. 4. Lyon: IARC; 2017. pp. 222–224. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Buchner A, Kaffe I, Vered M. Clinical and radiological profile of ameloblastic fibro-odontoma: an update on an uncommon odontogenic tumor based on a critical analysis of 114 cases. Head Neck Pathol. 2013;7(1):54–63. doi: 10.1007/s12105-012-0397-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brown NA, Rolland D, McHugh JB, Weigelin HC, Zhao L, Lim MS, et al. Activating FGFR2-RAS-BRAF mutations in ameloblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(21):5517–5526. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brunner P, Bihl M, Jundt G, Baumhoer D, Hoeller S. BRAF p.V600E mutations are not unique to ameloblastoma and are shared by other odontogenic tumors with ameloblastic morphology. Oral Oncol. 2015;51(10):e77–e78. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.You Z, Xu LL, Li XF, Zhang JY, Du J, Sun LS. BRAF gene mutations in ameloblastic fibromas. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2019;51(1):4–8. doi: 10.19723/j.issn.1671-167X.2019.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Agaimy A, Skalova A, Franchi A, Alshagroud R, Gill AJ, Stoehr R, et al. Ameloblastic fibrosarcoma: clinicopathological and molecular analysis of seven cases highlighting frequent BRAF and occasional NRAS mutations. Histopathology. 2020;76(6):814–821. doi: 10.1111/his.14053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chaudhary Z, Krishnan S, Sharma P, Sharma R, Kumar P. A review of literature on ameloblastoma in children and adolescents and a rare case report of ameloblastoma in a 3-year-old child. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2012;5(3):161–168. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1313358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lawal AO, Adisa AO, Popoola BO. Odontogenic tumours in children and adolescents: a review of forty-eight cases. Ann Ib Postgrad Med. 2013;11(1):7–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Philipsen HP, Reichart PA. Unicystic ameloblastoma. A review of 193 cases from the literature. Oral Oncol. 1998;34(5):317–325. doi: 10.1016/S1368-8375(98)00012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang R, Tang Y, Zhang X, Liu Z, Gokavarapu S, Lin C, et al. Recurrence factors in pediatric ameloblastoma: clinical features and a new classification system. Head Neck. 2019;41(10):3491–3498. doi: 10.1002/hed.25867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Philipsen HP, Reichart PA, Siar CH, Ng KH, Lau SH, Zhang X, et al. An updated clinical and epidemiological profile of the adenomatoid odontogenic tumour: a collaborative retrospective study. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36(7):383–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Philipsen HP, Reichart PA. Adenomatoid odontogenic tumour: facts and figures. Oral Oncol. 1998;35(2):125–131. doi: 10.1016/S1368-8375(98)00111-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gomes CC, de Sousa SF, de Menezes GH, Duarte AP, Pereira Tdos S, Moreira RG, et al. Recurrent KRAS G12V pathogenic mutation in adenomatoid odontogenic tumours. Oral Oncol. 2016;56:e3–e5. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Coura BP, Bernardes VF, de Sousa SF, Franca JA, Pereira NB, Pontes HAR, et al. KRAS mutations drive adenomatoid odontogenic tumor and are independent of clinicopathological features. Mod Pathol. 2019;32(6):799–806. doi: 10.1038/s41379-018-0194-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.El-Naggar A, Chan J, Grandis J, Takata T, Slootweg P, editors. WHO classification of head and neck tumours. 4 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ide F, Kikuchi K, Kusama K, Muramatsu T. Primordial odontogenic tumour: is it truly novel? Histopathology. 2015;66(4):603–604. doi: 10.1111/his.12595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ando T, Shrestha M, Nakamoto T, Uchisako K, Yamasaki S, Koizumi K, et al. A case of primordial odontogenic tumor: a new entity in the latest WHO classification (2017) Pathol Int. 2017;67(7):365–369. doi: 10.1111/pin.12543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bologna-Molina R, Pereira-Prado V, Sanchez-Romero C, Gonzalez-Gonzalez R, Mosqueda-Taylor A. Primordial odontogenic tumor: a systematic review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2020;25(3):e388–ee94. doi: 10.4317/medoral.23432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mikami T, Bologna-Molina R, Mosqueda-Taylor A, Ogawa I, Pereira-Prado V, Fujiwara N, et al. Pathogenesis of primordial odontogenic tumour based on tumourigenesis and odontogenesis. Oral Dis. 2018;24(7):1226–1234. doi: 10.1111/odi.12914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]