Abstract

Introduction

Transferring genes safely, targeting cells and achieving efficient transfection are urgent problems in gene therapy that need to be solved. Combining microbubbles (MBs) and viruses to construct double vectors has become a promising approach for gene delivery. Understanding the characteristic performance of MBs that carry genes is key to promoting effective gene transfer. Therefore, in this study, we constructed MB-adenovirus vectors and discussed their general characteristics.

Methods

We constructed MB-adenovirus vectors carrying the chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 12 (Cxcl12) and bone morphogenetic protein-2 (Bmp2) genes (pAd-Cxcl12 and pAd-Bmp2, respectively) to explore the general characteristics of double vectors carrying genes.

Results

The MB-adenovirus vectors had stable physical properties, and no significant differences in diameter, concentration, or pH were noted compared with naked MBs (p > 0.05). Flow cytometry and RT-PCR were used to detect the gene-loading capacity of MBs. The gene-loading efficiency of MBs increased with increasing virus amounts and was highest (91%) when 10.0 µL of virus was added. Beyond 10.0 µL of added virus, the gene-loading efficiency of MBs decreased with the continuous addition of virus. The maximum amounts of pAd-Cxcl12 and pAd-Bmp2 in 100 µL of MBs were approximately 14 and 10 µL, respectively.

Conclusions

This study indicates that addition of an inappropriate viral load will result in low MB loading efficiency, and the maximum amount of genes loaded by MBs may differ based on the genes carried by the virus.

Keywords: Ultrasound, Microbubbles, Gene vector, Gene-loading efficiency

Introduction

In recent years, gene therapy technology has become a potential method for disease treatment.9,10 However, transferring genes safely, targeting genes to cells, and achieving efficient transfection are urgent problems requiring resolution in the development of gene therapy. Viruses are promising gene therapy vectors because of their high transfection efficiency. However, the use of viruses in humans is limited by their poor organ targeting and rapid immune clearance in vivo.13,14 A relatively novel approach to targeting viruses or nucleic acids to specific regions in the body is the use of ultrasound and microbubbles (MBs). MBs are gas-filled spheres with a stabilizing lipid, protein, or polymer shell. When these MBs enter an ultrasonic field, they start to oscillate, expand and compress or even implode and fragment. As a vector, MBs can release genes to achieve gene-targeted transfection after ultrasonic directional irradiation.21 However, studies have confirmed that the transfection efficiency still needs to be improved.16

Based on the characteristics of MBs and virus vectors, construction of MB-viral vectors for targeted gene delivery has become a focus of research.11 Virus-loaded MBs can be obtained by coupling virus to the MBs. Upon ultrasound-mediated implosion of the MBs, the virus will be released and deliver its nucleic acids in the ultrasound-targeted region.7 At present, most related studies focus on the transfection efficiency and ultrasound-triggered release of MB-viral vectors.8,12,17 Geers7 reviewed the major factors affecting ultrasonic drug delivery (such as the MB structure and acoustic settings). In general, a high nucleic acid concentration is needed to obtain a satisfactory biological effect because of enzymatic degradation or immunity.5 To obtain a high concentration of genes near the target cells, researchers designed MBs with different components that were loaded with nucleic acids.6,19 Furthermore, the concentration of nucleic acid added to MBs also affects the transfection effect when preparing gene-loaded MBs. In addition, carrying different substances may affect the encapsulation efficiency of MBs, thus affecting the nucleic acid concentration carried by MBs. He et al.24 found that the efficiency of gene transfection was highest when the concentrations of MBs and plasmid were 150 and 20 µL/mL, respectively. Ren et al.17 compared lipid ultrasound MBs carrying genes with transactivating transcriptional activator (Tat) peptide and found that the gene encapsulation efficiency of the lipid ultrasound MBs was 32% and that the Tat encapsulation efficiency was 35%. However, few studies have focused on the general properties and characterization of the gene-loading capacity when constructing MB-virus vectors. Several aspects about MBs carrying viruses, such as the general gene-loading efficiency of MBs when different amounts of viruses are added and whether the gene-loading efficiency of MBs carrying different viruses varies, require further exploration.3

Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 12 (Cxcl12) is a chemokine that induces the recruitment of stem cells into the damaged tissues to repair ischemic myocardium.12 On the other hand, bone morphogenetic protein 2 (Bmp2) plays a critical role in the myocardial differentiation of stem cells15 by regulating the expression of cardiac-specific transcription factors.16. Considering that either the recruitment or the myocardial differentiation of stem cells is critical for myocardial repair, the delivery of Cxcl12 and Bmp2 genes into the infarcted heart may further enhance functional myocardial repair. Therefore, in this study, two types of MB-adenovirus complexes carrying different genes were constructed, including the Cxcl12 gene and the Bmp2 gene, which were carried by recombinant adenoviruses. By comparing the gene-loading capacities of MBs, we hope to determine the optimal amount of virus for use when constructing MB-viral vectors to provide an experimental basis for the application of MB vectors in subsequent gene-targeted therapy.

Materials and Methods

Biotin-Labeled Adenovirus

Recombinant adenoviruses (pAd) carrying the Cxcl12 gene (pAd-Cxcl12) or Bmp2 (pAd-Bmp2) gene were constructed at Source Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China).22 Both pAd-Cxcl12 and pAd-Bmp2 were biotinylated and had a titer of 1 × 109 pfu/mL. Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) or tetramethylrhodamine (TRITC) dye was used to label the virus.25 In brief, the recombinant adenovirus was allowed to reach room temperature. According to the manufacturer’s instructions, 1 mg of EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-LC-biotin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA) was weighed and dissolved in 224 µL of sterile pure water to prepare a 10 mM solution of the biotin reagent. FITC dye (1 mg) was dissolved in 100 µL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Biotin reagent (5 µL) and 20 µL of FITC dye solution were slowly added to 500 µL of pAd-Cxcl12 solution and allowed to react for 1 h in the dark at room temperature with continuous stirring. To remove unbound biotin and dye, the above reaction solution was dialyzed with PBS-MK buffer (pH 7.4) in Slide-A-Lyzer dialysis cassettes (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA) at 4 °C overnight. Dialyzed bioviruses were concentrated the next day and stored in the dark at −80 °C. A similar protocol was used to prepare fluorescent biotin-labeled pAd-Bmp2 by adding biotin and TRITC.

Preparation of MB-Adenovirus Vectors

The concentration of streptavidin-coated MBs (TargestarTM-SA, Targeson, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) was approximately 1 × 109 MB/mL.2 Before use, the MBs were gently shaken for 30 min. Different volumes (0.625, 1.25, 2.50, 5.00, 10.00, 20.00 or 30.00 µL) of biotinylated adenovirus (pAd-Cxcl12 or pAd-Bmp2) were added to 100 µL of MBs. The titer of both pAd-Cxcl12 and pAd-Bmp2 was 1 × 109 pfu/mL. The solution was incubated for 20 min at 25 °C with constant shaking. After adding 2 mL of PBS and centrifugation at 500 g for 5 min, the unconjugated adenovirus in the lower layer was removed, and the purified MB-adenovirus vector was obtained.4,23

Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy

pAd-Cxcl12 was labeled with FITC, and pAd-Bmp2 was labeled with TRITC. The combination of MBs and viruses was observed using laser confocal fluorescence microscopy (Zeiss Co., Oberkochen, Germany). Photographs of five random microscopic fields were obtained under 40× magnification, and the percentage of fluorescent MBs among the total MBs was measured with ImageJ software.

Physical Characterization of MB-Adenovirus Vectors

The purified MB-adenovirus vector was resuspended in PBS. The diameter and concentration of the MB-adenovirus complexes were determined using the AccuSizer particle size analysis and counting apparatus (Particle Sizing Systems, Port Richey, FL, USA). The pH value of the MB-adenovirus solution was measured using a pH meter (UB-10, Denver, CO, USA).

Gene-Loading Efficiency of MBs

The gene loading capacity of MBs was evaluated as previously described.22,23 After adding the virus to the MB solution, the MBs floated on the top of the suspension due to their lighter weight; therefore, centrifugation could be used to purify the MB-adenovirus vectors. First, after incubating the mixture for 20 min, 20 µL of the upper layer of the mixture was extracted as an unwashed sample. Then, the remaining mixture was added to 2 mL of PBS and centrifuged at 500 g to form two phases: an upper milky-white layer containing the MBs bound to adenovirus and a lower clear layer containing unbound adenovirus. The lower layer was discarded. The upper layer was resuspended in PBS, and 20 µL of the mixture was extracted after the washed sample was allowed to stand. After removing the MBs by ultrasonic spallation (1.5 MHz, 2 W, 15 s), all samples were measured to determine the gene-loading amounts of the MBs via real-time PCR, and the gene-loading efficiency of MBs was evaluated by comparing the amount of DNA in the washed samples to that in the unwashed samples.

Proportion of MBs Carrying the Virus

Flow cytometry (FACS Diva Version 6.1.3, Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA) was used to detect the proportion of MBs that successfully combined with virus after washing.22 As the virus was fluorescently labeled, the number of fluorescent MBs detected by flow cytometry reflected the proportion of MBs carrying the virus and was calculated as follows: proportion of MBs carrying the virus = (number of fluorescent MBs/total number of MBs) × 100%.

Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± SD. A t test was used for comparisons between two groups. Comparisons among multiple groups were performed using ANOVA. Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 23.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) software, and a value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All experiments were repeated at least three times.

Results

Binding of Viruses to MBs

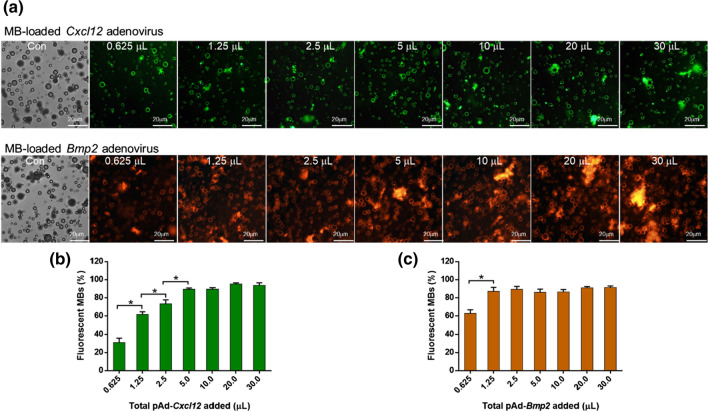

To visualize the binding of viruses to MBs, pAd-Cxcl12 was labeled with FITC, which emitted bright green fluorescence, and pAd-Bmp2 was labeled with TRITC, which emitted red fluorescence. Green fluorescence on the surface of MBs represented successful attachment of pAd-Cxcl12 onto the MBs, and pAd-Bmp2 was detected similarly. The MB shell is smooth, round and almost uniform in size. As the added amount of virus increased, the number of MBs emitting fluorescence gradually increased, and several clusters of MBs were observed. When the addition of pAd-Cxcl12 and pAd-Bmp2 exceeded 5 µL and 1.25 µL, respectively, the number of fluorescent MBs did not change substantially, even when virus was added continuously, and fluorescence union could be observed around some MBs (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Binding of viruses to microbubbles (MBs). (a) Confocal laser scanning microscope bright-field images and the corresponding fluorescence image of MBs carrying the Cxcl12 or Bmp2 adenovirus after the addition of 0.625, 1.25, 2.5, 5, 10, 20 or 30 µL of virus. pAd-Cxcl12 was labeled with FITC, which emitted bright green fluorescence, and pAd-BMP2 was labeled with TRITC, which emitted red fluorescence. Bar, 20 µm. The proportions of MBs successfully carrying (b) pAd-Cxcl12 or (c) pAd-BMP2 among the total MBs when different volumes of virus were added are shown. n = 3; *: p < 0.05.

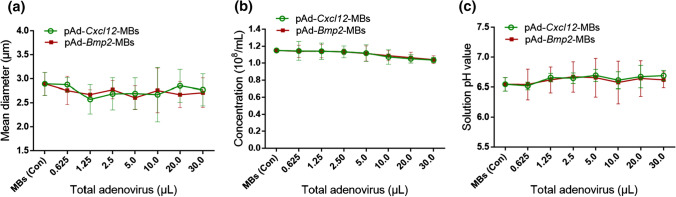

Physical Characterizations of MB-Adenovirus Vectors

The mean diameter, concentration and pH value of the naked MBs were (2.89 ± 0.23) µm, (1.15 ± 0.01) × 108/mL and (6.55 ± 0.11), respectively. As the amount of virus added increased, the MB concentration gradually decreased, but the difference was not significant compared with the control group (naked MBs). The physical characteristics of the two types of MB-adenovirus vectors were similar to those of the naked MBs, reflecting the biophysical stability of gene-loaded MBs (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Physical characterization of microbubble (MB)-viral vectors. (a) The mean diameter, (b) concentration, and (c) pH value of MBs with or without virus were quantitatively measured for comparison. n = 3.

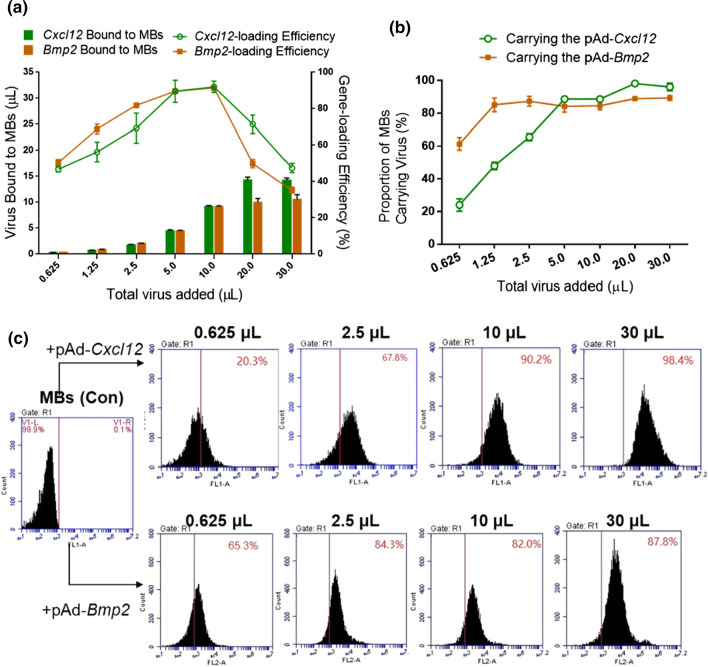

Gene-Loading Capacity of MBs

MBs Carrying Cxcl12

We tested the gene-loading efficiency of the MBs by adding different amounts of adenovirus into 100 µL of MBs. The PCR analysis suggested that the amount of pAd-Cxcl12 loaded into MBs increased rapidly with increasing virus amounts. When 20.0 µL of virus was added, the MBs carrying pAd-Cxcl12 reached saturation. In addition, the maximum viral amount loaded by MBs was approximately 14 µL, and the amount of MBs carrying the virus increased less with an increasing amount of virus addition. The line graph of the gene-loading efficiency shows that the addition of excess or too little virus will affect the gene-loading efficiency in MBs. The maximum gene-loading efficiency of MBs was nearly 90% when adding (5.0–10.0) µL of Cxcl12 adenovirus to 100 µL of MBs (Fig. 3a).

Figure 3.

The capacity of microbubbles (MBs) loaded with Cxcl12 or Bmp2 adenovirus. (a) RT-PCR analysis of the gene-carrying capacity of MBs after addition of 0.625, 1.25, 2.5, 5, 10, 20 or 30 µL of adenoviral vectors carrying Cxcl12 or Bmp2 genes into 100 µL of MBs. The virus titer was 1 × 109 pfu/mL. The bar graph shows the gene-loading amounts of the MBs. The line graph shows the gene-loading efficiency of the MBs, which was quantified by comparing the amount of DNA bound to MBs with the total amount of genes added. (b) Flow cytometry detection of the proportion of virus-carrying MBs, which is the proportion of MBs that successfully combined with adenovirus, and (c) a typical flow cytometry image of MBs carrying pAd-Cxcl12 (upper row) and pAd-Bmp2 (lower row). n = 3.

The flow cytometry results showed that the proportion of MBs carrying the virus increased rapidly with increasing amounts of added virus. Similar to the laser confocal microscopy results, when 5.0 µL of pAd-Cxcl12 was added, the proportion of MBs carrying virus was 88.6%. Then, the proportion of MBs carrying virus was only slightly changed with increasing virus amounts, and the highest proportion of MBs carrying the virus was 98.1% (Figs. 3b and 3c).

MBs Carrying Bmp2

The PCR analysis suggested that the amount of pAd-Bmp2 loaded by MBs increased with increasing virus addition. When 10.0 µL of virus was added, the MBs carrying pAd-Bmp2 reached saturation. In addition, the maximum amount of virus loaded by MBs was approximately 10 µL. Similar to the Cxcl12 results, the line graph showed that the addition of excess or too little pAd-Bmp2 will affect the gene-loading efficiency of MBs (Fig. 3a).

Similar to the laser confocal microscopy results, the flow cytometry showed that the proportion of MBs carrying virus reached 85.1% when 1.25 µL of pAd-Bmp2 was added to 100 µL of MBs. Then, the proportion of MBs carrying the virus only slightly changed with increasing virus addition, and the highest proportion of MBs carrying the virus was 89% (Figs. 3b and 3c).

Discussion

In gene-targeted therapy, the use of ultrasound MBs as gene carriers shows broad application prospects.1 An appropriate gene dosage is the premise of therapy, and the general characteristics and performance of MBs carrying genes are important factors that affect the research results.15,21 In this study, by constructing MB-adenovirus vectors, we analyzed the physical characteristics of MBs as a gene carrier and discussed the general characteristics of MB-adenovirus vectors, providing a theoretical basis for subsequent research on gene therapy.

The PCR results showed that the amount of genes carried by MBs increased with increasing virus addition, and the highest gene-loading efficiency was 91%. However, when the volumes of the Cxcl12 and Bmp2 adenoviruses were greater than 20 and 10 µL, respectively, the actual amount of genes that combined with MBs was no longer affected by increasing the amount of virus, suggesting saturation of the amount of genes carried by MBs. Furthermore, the gene-loading efficiency of MBs decreased sharply with additional virus, which likely occurred because the virus volume added far exceeded the MB loading capacity, and the excess free virus led to low gene-loading efficiency of MBs.18,20,22 Our results suggest that the capacity of MBs to carry genes is limited. Notably, when the amount of virus added was small, the gene-loading efficiency of MBs was also low, possibly because the concentration of virus in the solution was too low to adequately contact the MBs, resulting in low gene-loading efficiency. Additionally, the flow cytometry and laser confocal fluorescence microscopy results showed that most MBs failed to bind to the virus when a small amount of virus was added. Furthermore, the proportion of MBs that carried the virus, as detected by flow cytometry, was high only when the virus reached a certain level, further suggesting the importance of using an appropriate concentration range of virus in the construction of MB-viral vectors.

In a comparison of the dose-response performance of MBs carrying the two types of adenovirus, when the volume of virus was 10.0 µL, the amounts of the MBs carrying Cxcl12 and Bmp2 were similar (approximately 9 µL), and the gene-loading efficiency was highest. However, the MB loading capacity reached saturation when 20 µL of Cxcl12 or 10 µL of Bmp2 adenovirus was added, and the maximum amounts of virus loaded by MBs were approximately 14 and 10 µL, respectively (p < 0.05). The results above suggest that when MBs are loaded with different adenoviruses the amount of virus used to maximize the MB load and the maximum amount of virus that the MBs can carry may be different. Through further analysis, we found that the pentr-CMV-Cxcl12 and pentr-CMV-mkate2-Bmp2 fragments used in the construction of Cxcl12 and Bmp2 adenoviruses were 993 and 1,878 bp, respectively. Therefore, we speculate that the varying performance of the same MBs in carrying viruses may be related to differences in the target genes carried by the virus. However, further research is needed to confirm the conjecture that different lengths of the gene segment may affect the amount of genes carried by MBs.

Based on the results, the addition of 10 µL of virus (1 × 109 pfu/mL) to 100 µL of MBs (concentration 1 × 109/mL) achieved the highest gene-loading efficiency of MBs. This virus dose may be an appropriate dose reference. However, considering the varying performance of MBs in carrying different genes, the amount of virus used should also be “individualized” quantitatively in combination with the length of the genes. This will ensure efficient combination of MBs and viruses, thus avoiding wasting genes or MBs due to the addition of a nonoptimal amount of virus, and improve the gene transfection effect.26 In addition, the physical characteristics of the two types of gene-loaded MBs were similar to those of naked MBs, suggesting that the biophysical stability of the MB-adenovirus vector is not affected by the types of genes carried. In our study, the MB-virus mixture was centrifuged and washed after adding the virus to remove the free virus. During this process, some MBs might be ruptured, resulting in a decrease in the concentration of the MB-virus mixture.

In our study, the construction of MB-adenovirus vectors exploited the multivalent and high-affinity biotin-avidin interaction. To attach adenovirus to MBs, we first biotinylated the adenovirus particles using biotin–N-hydroxysuccinimide-ester (NHS) and then purified the particles by dialysis. NHS-activated biotins react efficiently with primary amino groups (–NH2) to form stable amide bonds. Biotin could specifically recognize lysine residues in the adenoviral capsid and label the adenovirus. The biotinylated adenovirus particles were then added to the MB solution. Streptavidin-coated MBs could bind to the biotinylated virus through avidin.1 We observed that some MBs clustered with increasing virus concentration. We speculate that the virus may be labeled by more than one biotin molecule simultaneously, and biotin molecules of one virus particle could combine with avidin of different MBs with increasing virus concentration in the solution, leading to the aggregation of MBs. The results demonstrated that virus-loaded MBs may aggregate when using the biotin-avidin bridge method to bind MBs and viruses. Furthermore, the formation of MB aggregates may affect the measured concentration of MBs.

However, some limitations exist in this study. First, although both FITC and TRITC are isothiocyanate dyes, the difference in binding of pAd-Cxcl12 and pAd-Bmp2 may be partly due to the different hydrophobicity of FITC and TRITC. Second, many types of ultrasound MBs can be used as carriers, and each type has different physical properties; meanwhile, the gene-carrying characteristics of different MBs may be vary due to differences in particle sizes, charges and materials. This study provides new perspectives and research references for follow-up studies. Third, we used the biotin-avidin bridge method to connect MBs and viruses in this study, and whether different linking methods affect the gene carrying abilities of MBs requires further comparative study. In addition, our study focused on the ability of MBs to carry viruses and the physical properties of MB-virus vectors. However, the dynamic behavior of the MB-adenovirus vector system, such as the permanency of the binding between virus and MBs and the release of virus from MBs, requires further discussion.

Conclusions

In brief, this study shows that an insufficient or excess amount of virus leads to low gene-loading efficiency of MBs. When MBs carry different genes, the maximum amount of genes loaded by MBs may vary. In addition, the physical properties of gene-loaded MBs are stable and not affected by the types of genes carried. Therefore, to maximize economy and efficiency, the virus dosage should be “individualized” when constructing gene-loaded MBs.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81460266, 81660289) and the Program of Autonomous Region (Science and Technology Aid Xinjiang Program, grant number 2018E02062).

Conflict of Interest

Lingjie Yang, Juan Ma, Lina Guan and Yuming Mu have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bez M, Foiret J, Shapiro G. Nonviral ultrasound-mediated gene delivery in small and large animal models. Nat. Protoc. 2019;14(4):1015–1026. doi: 10.1038/s41596-019-0125-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cavalli R, Bisazza A, Lembo D. Micro- and nanobubbles: a versatile non-viral platform for gene delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2013;456(2):437–445. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delalande A, Bastie C, Pigeon L, Manta S, Lebertre M, Mignet N, Midoux P, Pichon C. Cationic gas-filled microbubbles for ultrasound-based nucleic acids delivery. Biosci. Rep. 2017;37(6):BSR20160619. doi: 10.1042/bsr20160619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dewitte H, Roovers S, De Smedt SC, Lentacker I. Enhancing nucleic acid delivery with ultrasound and microbubbles. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019;1943:241–251. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-9092-4_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duvshani-Eshet M, Machluf M. Therapeutic ultrasound optimization for gene delivery: a key factor achieving nuclear DNA localization. J. Control. Release. 2005;108(2–3):513–528. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frenkel PA, Chen S, Thai T, Shohet RV, Grayburn PA. DNA-loaded albumin microbubbles enhance ultrasound-mediated transfection in vitro. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2002;28(6):817–822. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(02)00518-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geers B, Dewitte H, De Smedt SC, Lentacker I. Crucial factors and emerging concepts in ultrasound-triggered drug delivery. J. Control. Release. 2012;164(3):248–255. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geers B, Lentacker I, Alonso A, Meairs S, Demeester J, De Smedt SC, Sanders NN. Adeno-associated virus loaded microbubbles as a tool for targeted gene delivery. J. Control. Release. 2010;148(1):e59. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.High KA, Roncarolo MG. Gene Therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019;381(5):455–464. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1706910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishikawa K, Weber T, Hajjar RJ. Human cardiac gene therapy. Circ. Res. 2018;123(5):601–613. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.118.311587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li F, Jin L, Wang H, Wei F, Bai M, Shi Q, Du L. The dual effect of ultrasound-targeted microbubble destruction in mediating recombinant adeno-associated virus delivery in renal cell carcinoma: transfection enhancement and tumor inhibition. J. Gene Med. 2014;16(1–2):28–39. doi: 10.1002/jgm.2755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu J, Zhang B, Li M, Zhou M, Li F, Huang X, Pan M, Xue L, Yan F. Preparation and characterization of a novel silicon-modified nanobubble. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(5):e0178031. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lukashev AN, Zamyatnin AA., Jr Viral vectors for gene therapy: current state and clinical perspectives. Biochemistry (Mosc.) 2016;81(7):700–708. doi: 10.1134/s0006297916070063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naso MF, Tomkowicz B, Perry WL, III, Strohl WR. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) as a vector for gene therapy. Biodrugs. 2017;31(4):317–334. doi: 10.1007/s40259-017-0234-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Negishi Y, Endo-Takahashi Y, Maruyama K. Gene delivery systems by the combination of lipid bubbles and ultrasound. Drug Discov. Ther. 2016;10(5):248–255. doi: 10.5582/ddt.2016.01063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qian L, Thapa B, Hong J, Zhang Y, Zhu M, Chu M, Yao J, Xu D. The present and future role of ultrasound targeted microbubble destruction in preclinical studies of cardiac gene therapy. J. Thorac. Dis. 2018;10(2):1099–1111. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.01.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ren J, Xu C, Zhou Z, Zhang Y, Li X, Zheng Y, Ran H, Wang Z. A novel ultrasound microbubble carrying gene and Tat peptide: preparation and characterization. Acad. Radiol. 2009;16(12):1457–1465. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2009.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takayama Y, Kusamori K, Hayashi M, Tanabe N, Matsuura S, Tsujimura M, Katsumi H, Sakane T, Nishikawa M, Yamamoto A. Long-term drug modification to the surface of mesenchymal stem cells by the avidin-biotin complex method. Sci. Rep. 2017;7(1):16953. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-17166-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teupe C, Richter S, Fisslthaler B, Randriamboavonjy V, Ihling C, Fleming I, Busse R, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Vascular gene transfer of phosphomimetic endothelial nitric oxide synthase (S1177D) using ultrasound-enhanced destruction of plasmid-loaded microbubbles improves vasoreactivity. Circulation. 2002;105(9):1104–1109. doi: 10.1161/hc0902.104720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilchek M, Bayer EA. The avidin-biotin complex in bioanalytical applications. Anal. Biochem. 1988;171(1):1–32. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(88)90120-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu J, Li RK. Ultrasound-targeted microbubble destruction in gene therapy: A new tool to cure human diseases. Genes Dis. 2017;4(2):64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2016.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang LJ, Liu LY, Mu YM. Experimental study on construction of ultrasound microbubbles co-carrying pAd-EGFP/SDF-1α and pAd-RFP/BMP2. Chin. J. Ultrasonogr. 2016;25(11):1002–1007. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang L, Yan F, Ma J, Zhang J, Liu L, Guan L, Zheng H, Li T, Liang D, Mu Y. Ultrasound-targeted microbubble destruction-mediated co-delivery of Cxcl12 (Sdf-1alpha) and Bmp2 genes for myocardial repair. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2019;15(6):1299–1312. doi: 10.1166/jbn.2019.2776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ying H, Zhongxiong Z. Optimization of ultrasound microbubble and plasmid concentration for gene transfection. J. Ultrasound Clin. Med. 2016;18(07):433–437. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang H, Ran HT, Zhang YP, Luo J, Hao L, Wang Z-G. Preparation and application of polymer ultrasound contrast agents integrated with streptoavidin. Chin. J. Med. Imaging Technol. 2010;26(6):997–1000. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhi W. Status and progress of basic research for ultrasound contrast agent. Chinese Journal of Medical Ultrasound (Electronic Version) 2011;08(5):8–12. [Google Scholar]