Abstract

An example of a mandibular rhabdomyosarcoma in a 15-year-old male is described featuring EWSR1-TFCP2 fusion with homolateral lymph node metastasis and apparent metastasis to the thoracic vertebra T7. This type of rhabdomyosarcoma has preference for the craniofacial skeleton. Histologically, the tumor was composed of spindle and epithelioid cells characterized by nuclear pleomorphism, cytologic atypia and brisk mitotic activity. Immunohistochemically, it featured diffuse positive nuclear staining MYOD1, only focal staining for myogenin and patchy cytoplasmic staining for desmin. Tumor cells were positive for keratins and nuclear staining for SATB2 was also observed. Interestingly, tumor cells were diffusely positive for calponin. Currently, the patient is under chemotherapy treatment.

Keywords: Rhabdomyosarcoma, Mandible, EWSR1-TFCP2

Introduction

Advances in molecular pathology have resulted in identification of putative driver mutations in rhabdomyosarcoma (RS), the most frequent childhood soft tissue sarcoma with approximately 50% of the embryonal type occurring in the area of the head and neck [1]. The identification of such mutations in the two major subtypes of RS, embryonal (ERS) and alveolar (ARS), as well as in the less frequent variants such as spindle cell/sclerosing (SSRS), epithelioid (EPIRS) and pleomorphic (PRS) RS, not only play a role in classification, but they may be important for stratification of patients when it comes to predicting tumor progression and behavior, and for customized treatment given the availability, in certain instances, of gene targeted therapies. Briefly, mutations of the genes involved in the FGFR4/RAS/AKT pathway and high frequency PTEN hypermethylation are significant events in ERS, high frequency of FOXO1 fusions, PAX3-FOXO1 and PAX7-FOXO1, highlight the majority of cases of ARS [2], while SSRS is mostly characterized by VGLL2-related fusions [3] and MYOD1 mutations [4]. Very recently, SRF-FOXO1 and SRF-NCOA1 fusions have been described in 3 cases of well-differentiated RS highlighting the importance of molecular findings for prognosis [5].

A rare RS type featuring spindle and epithelioid cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm and characterized by EWSR1/FUS-TFCP2 fusions has been recently recognized [6–9] with the majority of cases reported in the craniofacial skeleton and especially the gnathic bones [9]. Since EWS and FUS proteins are members of the FET (FUS, EWS, TAF15) RNA-binding protein family [10], this subtype of RS has also been referred to as FET-TFCP2 RS [9]. Herein, we describe an additional mandibular example of FET-TFCP2 RS carrying the EWSR1-TFCP2 fusion, further expanding the number of cases reported thus far in the literature, with the purpose to alert colleagues of its morphologic characteristics and aggressive clinical behavior.

Case Report

A 15-year-old male presented in October of 2019 with pain in the left posterior mandible which was treated with tooth extraction. However, the pain and swelling continued and were attributed to postsurgical infection. Panoramic radiograph (Fig. 1) and CT scan revealed destructive left posterior mandibular radiolucency exhibiting moth eaten-like irregular and ill-defined borders and loss of both buccal and lingual plates thus suggesting an aggressive neoplasm. Positron emission tomography showed uptake in the mass and also in the ipsilateral cervical lymph nodes.

Fig. 1.

Panoramic radiograph reveals destructive lesion in the left posterior side of the mandible (arrow)

The patient’s medical history was significant for fetal hepatoblastoma, mixed epithelial/mesenchymal type, at age 2 years with lung metastasis, which was treated initially with Cisplatin, Doxorubicin, 5-Fluorouracil and Vincristine. The patient developed pulmonary recurrence 2 years later, which was treated with surgical resection of pulmonary metastases followed by chemotherapy with Irinotecan, Vincristine and Erlotinib as the tumor had high EGFR expression. The patient did well afterwards with no evidence of recurrence of his hepatoblastoma. Also, the patient presented with macrocephaly and delayed language and fine motor development. Li-Fraumeni syndrome was excluded by the Invitae sarcoma panel which detects alterations in 28 genes involved in sarcoma, including TP53, using sequencing and detection of deletions/dublications.

As there was considerable pain associated with the tumor, the clinical team opted to perform upfront debulking of the majority of the left mandibular mass. At gross, received were three white blood-tinged solid soft tissue fragments with attached surface epithelium that measured 7.0 × 1.8 × 1.0 cm in aggregate. Histopathologic preparations revealed fascicular and in areas storiform proliferation (Fig. 2a, b) of large mostly of spindle (Fig. 2c), occasionally epithelioid and less often round cells (Fig. 2d) with eosinophilic or amphophilic cytoplasm and generally well-defined plasmalemmal membranes. Individual cells exhibited spindle, ovoid or round vesicular or hyperchromatic nuclei, prominent and occasionally multiple nucleoli and atypical mitoses (Figs. 2e), with areas featuring > 10/HPF. Foci of necrosis were also present and rare calcifications (Fig. 2f), dystrophic or residual reactive bone fragments, were noted.

Fig. 2.

a Fascicular and in areas storiform proliferation of predominantly spindle cells. b Intersecting fascicles of predominantly spindle cells. c Fascicles composed of spindle cells featuring multiple atypical mitoses. d Mixed population of spindle, epithelioid and round cells. Epithelioid and round cells are present in the lower part of the picture. e Nuclear pleomorphism with nuclei featuring, occasionally, multiple nucleoli and brisk mitotic activity. f Rare woven bone spicule infiltrated by neoplastic cells. The bone may be reactive residual bone or focus of dystrophic bone formation characterized by osteoclasia

Immunohistochemical evaluation for skeletal muscle markers disclosed patchy but intense staining for desmin (Fig. 3a; DE-R-11, prediluted, Ventana, Tucson, AZ), diffuse nuclear staining for MyoD1 (Fig. 3b; 5.8A, prediluted, Leica Novocastra, Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom) but infrequent nuclear staining for myogenin (Fig. 3c; FD5, prediluted, Cell Marque, Rocklin, CA). Also observed were positive and of variable intensity cytoplasmic and peri-or paranuclear staining for AE1/AE3 cytokeratin cocktail (Fig. 3d; AE1 + A3, prediluted, DAKO, Carpinteria, CA), and diffuse and in areas intense cytoplasmic staining for calponin (Fig. 3e; CALP, 1:100, DAKO). Smooth muscle actin (1A4, prediluted, Ventana) and smooth muscle myosin (SMMS-1, prediluted, Ventana) were negative. Selective nuclear staining for SATB2 (Fig. 3f; EP281, prediluted, Cell Marque) that varied in intensity was also observed. Also diffuse nuclear positive staining was obtained with p53 (Fig. 3g; Bp53-11, prediluted, Ventana). Plasmalemmal staining for β-catenin (Fig. 3h; 14, prediluted, Ventana) was diffuse while ALK-1 (ALK-1, 1:50, DAKO) was negative. Neoplastic cells revealed the presence of lysosomes decorated by CD68 (PGM-1, prediluted, DAKO). S100 (polyclonal, prediluted, Ventana), CD34 (Qbend/10, prediluted, Ventana), and ERG (EPR3864, prediluted, Ventana) were negative.

Fig. 3.

a Patchy staining of spindle and epithelioid cells with desmin. b Most neoplastic cell nuclei were stained with MyoD1. c Only few nuclei were positive for myogenin. d Cytoplasmic and perinuclear staining of neoplastic cells with cytokeratin amntibody AE1/AE3. e Diffuse cytoplasmic staining of neoplastic cells for calponin. f Nuclear staining with SATB2 was observed in many neoplastic cells. g Diffuse nuclear staining with p53. h Plasmalemmal staining for β-catenin

Paraffin tissue block was forwarded to FoundationOne®CDx for genomic evaluation which disclosed EWSR-TFCP2 fusion with TP53-Y236H (706T > C) mutation and harboring a tumor mutational burden of 2 mutations/megabase. The molecular signature of the tumor revealed other variants of, however presently, unknown significance including, per report, ABL1 (K867R), ARID2 (S1618Y), FGF4 (S54L), FGFR2 (R165W), FGFR4 (V288I), FLT1 (T770S), IRF8 (R284W), LRP1B (K452N and M131I), MKI67 (P1935S), PTCH1 (L1397I), ROS1 (G1027D) and SDHD (T112I). Based on the Foundation One®CDx report there was no available targeted therapy.

The patient underwent surgical resection of the tumor, maintaining the mandibular joint and underwent left hemimandibulectomy reconstruction with fibular free flap. Homolateral lymph node dissection was also done which revealed 2/8 Level 1 and 2/13 Level 4 positive lymph nodes (Fig. 4). The patient was treated with combination chemotherapy by alternating courses of Vincristine, Actinomycin D and Cyclophosphamide with courses of Etoposide and Ifosfamide. Alternating Etoposide/Ifosfamide with Vincristine, Actinomycin D and Cyclophosphamide offered the possibility of decreasing cumulative toxicity of any one chemotherapeutic agent. Doxorubicin was not used in the treatment regimen because of previous therapy with Doxorubicin (total dose 240 mg/m2) and the finding of decreased cardiac function on follow-up echocardiogram.

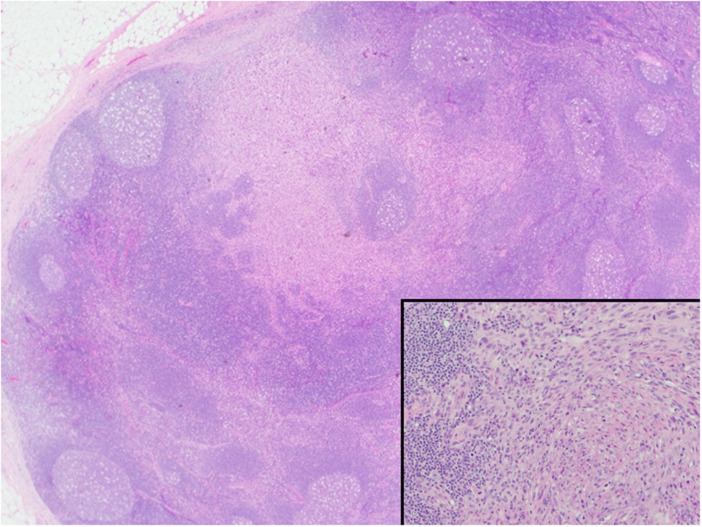

Fig. 4.

Low power microphotograph of lymph node metastasis. (insert). High power reveals infiltrated lymph node by RS characterized by spindle, epithelioid and few round cells

In preparation for local control with proton beam therapy, imaging was repeated and showed an area of new uptake in the anterior aspect of thoracic vertebra T7 transverse process. MRI showed a small soft tissue mass strongly suggestive of metastasis. The patient received proton beam therapy to the left mandible tumor site, left involved cervical lymph node chain and the metastatic lesion at T7. Because the patient’s disease progressed on chemotherapy, it was decided to switch his chemotherapy to Irinotecan and Temozolamide. The patient remains on ongoing therapy.

Discussion

Primary intraosseous RS are exceedingly rare. However, the head and neck skeleton is the most frequently involved site which may be expected given the preponderance of RS for the head and neck including the oral mucosa [9]. Recently, examples of intraosseous RS with a distinctive spindle, epithelioid and less often round cytomorphology and FET-TFCP2 gene fusions have been described [7–9]. These tumors are aggressive and frequently the patients experience metastatic disease with more than 60% of them dying of the disease [9].

Table 1 summarizes the clinicopathologic and molecular findings of craniofacial FET-TFCP2 RS reported in the literature [6–9, 11, 12]. Briefly, 16 patients have been reported in the literature, nine females and 7 males, with age distribution 11–72 years and average age of 30.63 years (SD: ± 20.21). The most common location is the mandible. One case has been designated as hard palate and gingiva. Histologically, eleven cases featured both spindle and epithelioid cells, three epithelioid or ovoid phenotype while two were purely spindle.

Table 1.

Reported individuals with craniofacial rhabdomyosarcomas exhibiting FET-TFCP2

| Gender/age | Location | Cytology | Fusion | Follow-up information | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Le Loarer et al. [9] | 16Fa | Sphenoid bone | Spindle and epithelioid | FUS-TFCP2 | DOD (15 mo) |

| Le Loarer et al. [9] | 32M | Hard palate and gingiva | Spindle and epithelioid | EWSR1-TFCP2 | DOD (8 mo) |

| Le Loarer et al. [9] | 20M | Orbito-temporo-sphenoid area | Spindle and epithelioid | FUS-TFCP2 | DOD (6 mo) |

| Le Loarer et al. [9] | 17Fb | Cervico-occipital area | Rounded | FUS-TFCP2 | AWD (15 mo) |

| Le Loarer et al. [9] | 31M | Occipital bone | Spindle and epithelioid | FUS-TFCP2 | DOD (6mo) |

| Le Loarer et al. [9] | 32M | Mandible | Spindled | FUS-TFCP2 | AWD (14 mo) |

| Le Loarer et al. [9] | 58F | Mandible | Spindle and epithelioid | FUS-TFCP2 | ANED (21 mo) |

| Le Loarer et al. [9] | 12F | Mandible | Spindle and epithelioid | FUS-TFCP2 | ANED (21 mo) |

| Le Loarer et al. [9] | 11F | Maxilla | Epithelioid | EWSR1-TFCP2 | DOD (Unknown) |

| Le Loarer et al. [9] | 25M | Mandible | Epithelioid | EWSR1-TFCP2 | ANED (20 mo) |

| Zhu et al. [11] | 74F | Maxilla | Oval to spindle | FUS-TFCP2 | Unknown |

| Dashti et al. [7] | 72M | Mandible | Spindle | FUS-TFCP2 | ANED (2 mo) |

| Agaram et al. [4] | 33F | Maxilla | Ovoid to short spindle | EWSR1-TFCP2 | NED (108 mo) |

| Agaram et al. [4] | 27F | Skull | Spindle and epithelioid | EWSR1-TFCP2 | Unknown |

| Flaitz et al. [12] | 15F | Mandible | Spindle and epithelioid | FUS-TFCP2 | Unknown |

| Present case | 15M | Mandible | Spindle and epithelioid | EWSR1-TFCP2 | AWD (7 mo) |

DOD dead of disease, AWD alive with disease, ANED alive no evidence of disease

aInitially reported by Watson et al. [6]

bSubsequently reported by Brunac et al. as an example successfully responding to radiation and ALK inhibitor treatment

Skeletal muscle immunohistochemistry for FET-TFCP2 RS has revealed diffuse staining with Myo-D1, variable nuclear staining with myogenin that in our example was focal, and cytoplasmic staining with desmin which was also patchy in our preparation. We concur with other reports that Myo-D1 is the most sensitive among skeletal muscle markers and should be included in the immunohistochemical panel [8, 9]. Positive pancytokeratin AE1/AE3, frequently strong and diffuse, is observed in FET-TFCP2 RS [7–9] as it is also generally the case in RS. Positive staining for keratin cocktail, however, may have diagnostic and clinical implications in the absence of a skeletal muscle panel which will support the diagnosis of anaplastic spindle cell carcinoma over RS.

Staining for calponin was also observed in our case with all other performed smooth muscle markers being negative. Notwithstanding the possibility of non-specific staining by the CALP antibody, the positive staining observed may be the result of affinity of calponin with alpha-actinin-actin and filamin, two proteins observed in skeletal muscle with tandem calponin homology domains [13]. It is also possible that these neoplastic cells express calponin in a manner similar to inflammatory leiomyosarcoma (low-grade inflammatory myogenic tumor), a very rare and somewhat indolent soft tissue tumor expressing skeletal muscle markers [14]. Among reported cases of FET-TFCP2 RS there is one example of FUS-TFCP2 RS of the maxillary gingiva displaying a myogenic profile that included smooth muscle actin and caldesmon [11]. That tumor was negative for keratin. Of interest is also a case of an apparent epithelioid rhabdomyosarcoma of the mandible which was positive for h-caldesmon and smooth muscle actin [15]. However, molecular analysis was not performed.

Nuclear reaction for SATB2 has not been reported in the literature in the few cases of RS where such stains were performed, specifically SSRS and pleomorphic RS [16, 17]. SATB2 is not observed in normal skeletal muscle nuclei nor in smooth or heart muscle. Although the importance of this reaction in our patient is unknown, one should note that SATB2 is a nuclear partner of Zfp423, a transcriptional factor which, besides participating in adipocytic and, when suppressed, osteoblastic lineage commitment, is essential in muscle regeneration [18]. Tight regulation of Zfp423 is essential for normal progression of muscle progenitors from proliferation to differentiation [18].

ALK upregulation [7, 8] have been reported in both ERS and ARS. In the largest study of FET-TFCP2 RS to this date [9] ALK overexpression has been observed in the majority of cases, 11 out 14 (78.5%), both at the transcription and protein levels due to ALK genomic deletion as a result of apparent alternative transcription initiation. ALK positivity has been observed in all other individual cases reported in the gnathic bones [7–9]. However, positive immunostaining for ALK does not always suggest ALK rearrangement [9]. Patients with FET-TFCP2 RS and ALK upregulation may be benefited with use of ALK inhibitors, e.g. alectinib [9, 19]. Since chemotherapy for intraosseous rhabdomyosarcoma is not well established, it was decided to treat the patient presented herein with chemotherapy effective for rhabdomyosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma. The TP53 mutation identified in our patient probably does not represent a targetable alteration in this tumor and most likely confers an aggressive phenotype and resistance to chemotherapy [20].

The genes of the FET RNA-binding protein family are found to be involved in deleterious genomic rearrangements with other transcription factor genes in a variety of carcinomas, sarcomas and in acute leukemia [10]. Fusions of FET proteins with various transcription factors are well described in the literature, e.g. EWS-FLI1 in Ewing sarcoma. Both EWS and FUS are expressed in skeletal and smooth muscle nuclei [21]. It is also hypothesized that Ewing sarcoma may be a tumor of mammalian muscle progenitor cell origin [22] because of expression of PAX7, a rhabdomyosarcoma marker. EWSR1-DUX4 fusion has been described in one example of RS [23]. These findings suggest the EWSR1 aberrations, although rare, could be expected in RS. Most FET-TFCP2 RS are hybrid spindle/epithelioid tumors and FUS-TFCP2 is most frequently encountered in craniofacial RS.

TFCP2 (transcription factor cellular promoter 2), also known as CP2, TFCP2C, LSF(late simian virus 40 [SV40] factor), LBP-1c (leader binding protein1c) and LBP-1d [24], is a member of the Grainyhead-like (GRHL) transcription factors and is important for (a) organ development, e.g. as a coordinator in the development of epithelial, intercalated and principal cells in the kidney collecting ducts, ductal cell maturation and branching in salivary glands, (b) mammalian sex determination by affecting SRY transcription, folliculogenesis and spermatogenesis/ spermatogonia, (c) maintenance of the pluripotency of embryonic stem cells in mice [25], (d) epithelial-mesenchymal transition [26, 27], and (e) tumor metastasis [27]. In breast cancer, TFCP2 regulates the expression of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and, through the TFCP2/EGFR/PI3K/AKT axis mechanism when overexpressed, increased migration/invasion of tumor cells are observed [27]. AKT serves as an upstream regulator. TFCP2 is overexpressed in most cases of hepatocellular carcinoma [28] and pancreatic cancer [29] and the expression levels correlate with progression of disease [28, 29]. Also, TFCP2 is upregulated in oral squamous cell carcinoma [30]. Interestingly, TFCP2 plays a protective role against melanoma [31] acting as a tumor suppressor of the death-associated protein kinase (DAPK) gene, the methylation of which can abolish TFCP2 binding [32]. It has been also shown that in mouse mesenchymal stem cell line C3H10T1/2 TFCP2 regulates bone morphogenetic protein 4, a key regulator of cell fate and body patterning throughout development, including regulation of osteoblastic differentiation [33]. This may further explain the nuclear reaction of tumor cells in the present tumor for SATB2. Also, SPP1, the gene encoding osteopontin, can be induced by TFCP2 [28]. The presence of rare calcifications identified in the present tumor may be the result of such actions of the TFCP2.

The function of the fusion protein product and the effect of FET-TFCP2 fusion on other genes is currently unknown. One can speculate that a mutated stem cell with FET-TFCP2 develops a myogenic phenotype through EWSR1 or FUS which because of the TFCP2 features accelerated tumor cell motility, invasion and metastasis commonly seen in FET-TFCP2 RS. Also, the presence of two cell populations, epithelioid (round) and spindle, may be explained by the action of TFCP2 as an EMT regulator. EWSR1 and FUS are involved without being individually related with a specific histopathologic phenotype, i.e. spindle cell vs. epithelioid [6].

Besides FET-TFCP2 RS another type of intraosseous RS characterized by MEIS1-NCOA2 has been recently described [8]. MEIS1-NCOA2 RS features only spindle cells that are cytokeratin and ALK negative. The number reported in the literature is small, two, and the location in both cases was the iliac bone [8].

In summary, we presented an additional example of FET-TFCP2 RS of the craniofacial skeleton to raise awareness of this aggressive neoplasm with generally poor prognosis. It is apparent that diagnosis of sarcomas, including those developing in bone should be investigated, when possible, for specific gene abnormalities to aid diagnosis, provide prognostic information, and/or identify gene-specific targeted therapies.

Acknowledgement

We are indebted to Mr. Brian Dunnette for his help with the illustrations.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Miettinen M, Fetch JF, Antonescu CR, Folpe AL, Wakely PE., Jr . Rhabdomyosarcoma. In: Miettinen M, Fetch JF, Antonescu CR, Folpe AL, Wakely PE Jr, editors. Tumors of the soft tissues. AFIP Atlas Of Tumor Pathology, vol 4, pp 291–304. Silver Spring, MD: American Registry of Pathology; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kohashi K, Kinoshita I, Oda Y. Soft tissue special issue: skeletal muscle tumors: a clinicopathological review. Head Neck Pathol. 2020;14:12–20. doi: 10.1007/s12105-019-01113-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alaggio R, Zhang L, Sung Y-S, et al. A Molecular study of pediatric spindle and sclerosing rhabdomyosarcoma: identification of novel and recurrent VGLL2-related fusions in infantile cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:224–235. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agaram N, LaQuaglia MP, Alaggio R, et al. MYOD1-mutant spindle cell and sclerosing rhabdomyosarcoma: an aggressive subtype irrespective of age. A reappraisal for molecular classification and risk stratification. Mod Pathol. 2019;32:27–36. doi: 10.1038/s41379-018-0120-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karanian M, Pissaloux D, Gomez-Brouchet A, et al. SRF-FOXO1 and SRF-NCOA1 fusion genes delineate a distinctive subset of well-differentiated rhabdomyosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2020;44:607–616. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watson S, Perrin V, Guillemot D, et al. Transcriptomic definition of molecular subgroups of small round cell sarcomas. J Pathol. 2018;245:29–40. doi: 10.1002/path.5053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dashti NK, Wehrs RN, Thomas BC, et al. Spindle cell rhabdomyosarcoma of bone with FUS-TFCP2 fusion: confirmation of a very recently described rhabdomyosarcoma subtype. Histopathol. 2018;73:514–520. doi: 10.1111/his.13649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agaram N, Zhang L, Sung Y-S, et al. Expanding the spectrum of intraosseous rhabdomyosarcoma. Correlation between 2 distinct gene fusions and phenotype. Am J Surg Pathol. 2019;43:695–702. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Le Loarer F, Cleven AHG, Bouvier C, et al. A subset of epithelioid and spindle cell rhabdomyosarcomas is associated with TFCP2 fusions and common ALK upregulation. Mod Pathol. 2020;33:404–419. doi: 10.1038/s41379-019-0323-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kovar H. Dr. Jeckyll and Mr. Hyde: the two faces of the FUS/EWS/TAF15 protein family. Sarcoma. 2011;2011:837474. doi: 10.1155/2011/837474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu G, Benayed R, Ho C, et al. Diagnosis of known sarcoma fusions and novel fusion partners by targeted RNA sequencing with identification of a recurrent ACTB-FOSB fusion in pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma. Mod Pathol. 2019;32:609–620. doi: 10.1038/s41379-018-0175-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flaitz CM, Hicks MJ. Primary intraosseous rhabdomyosarcoma: rare subtype involving mandible with unique translocation. 74th Annual Meeting, American Academy of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, Nashville; Abstract ID:43; poster No:55; 2020

- 13.Leinweber B, Tang JX, Stafford WF, Chalovich JM. Calponin interaction with alpha-actinin-actin: evidence for a structural role for calponin. Biophys J. 1999;77:3208–3217. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77151-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Michal M, Rubin BP, Kazakov DV, et al. Inflammatory leiomyosarcoma shows frequent co-expression of smooth and skeletal muscle markers supporting a primitive myogenic phenotype: a report of 9 cases with a proposal for reclassification as low-grade inflammatory myogenic tumor. Virchows Arch. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00428-020-02774-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Aguiar MCF, de Noronha MS, Silveira RL, et al. Epithelioid rhabdomyosarcoma: report of the first case in the jaw. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2020.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis JL, Horvai AE. Special AT-rich sequence-binding protein 2 (SATB2) expression is sensitive but may not be specific for osteosarcoma as compared with other high-grade primary bone sarcomas. Histopathology. 2016;69:84–90. doi: 10.1111/his.12911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hornick JL. Novel uses of immunohistochemistry in the diagnosis and classification of soft tissue tumors. Mod Pathol. 2014;27(Suppl 1):47–63. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Addison WN, Hall KC, Matsubara T, et al. Zfp423 regulates skeletal muscle regeneration and proliferation. Mol Cell Biol. 2019;39:e00447–e518. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00447-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brunac AC, Laprie A, Castex MP, et al. The combination of radiotherapy and ALK inhibitors is effective in the treatment of intraosseous rhabdomyosarcoma with FUS-TFCP2 fusion transcript. Periatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67:e28185. doi: 10.1002/pbc.28185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou X, Hao Q, Lu H. Mutant p53 in cancer therapy-the barrier or the path. J Mol Cell Biol. 2019;11:293–305. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjy072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andersson MK, Ståhlberg S, Arvidsson Y, et al. The multifunctional FUS, EWS and TAF15 proto-oncoproteins show cell type-specific expression pattercs and involvement in cell spreading and stress response. BMC Cell Biol. 2008;9:37. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-9-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charville GW, Wang W-L, Ingram DR, et al. EWSR1 fusion proteins mediate PAX7 expression in Ewing sarcoma. Mod Pathol. 2017;30:1312–1320. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2017.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sirvent N, Trassard M, Ebran N, Attias R, Pedeutour F. Fusion of EWSR1 with the DUX4 facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy region resulting from t(4;22)(q35;q12) in a case of embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2009;195:12–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kotarba G, Krzywinska E, Grabowska AI, Taracha A, Wilanowski T. TFCP2/TFCP2L1/UBP1 transcription factors in cancer. Cancer Lett. 2018;420:72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2018.01.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taracha A, Kotarba G, Wilanowski T. Neglected functions of TFCP2/TFCP2L1/UBP1 transcription factors may offer valuable insights into their mechanisms of action. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:E2852. doi: 10.3390/ijms19102852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Porta-de-la-Riva M, Stanisavljevic J, Curto J, et al. TFCP2c/LSF/LBP-1c is required for Snail1-induced fibronectin gene expression. Biochem J. 2011;435:563–568. doi: 10.1042/BJ20102057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao Y, Kaushik N, Kang JH, et al. A feedback loop comprising EGF/TGF-α sustains TFCP2-mediated breast cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2020 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-2908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoo BK, Emdad L, Gredler R, et al. Transcription factor Late SV40 Factor (LSF) functions as an oncogene in hepatocellular carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:8357–8362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000374107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yuedi D, Yuankun C, Jiaying Z, et al. TFCP2 activates beta-catenin/TCF signaling in the progression of pancreatic cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:70538–70549. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.19741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen C-H, Tsai H-T, Chuang H-C, et al. Metformin disrupts malignant behavior of oral squamous cell carcinoma via a novel signaling involving late SV40 factor/Aurora A. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1358. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01353-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goto Y, Yajima I, Kumasaka M, et al. Transforming factor LSF (TFCP2) inhibits melanoma growth. Oncotarget. 2016;7:2379–2390. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pulling LC, Grimes MJ, Damiani LA, et al. Dual promoter regulation of death-associated protein kinase gene leads to differentially silenced transcripts by methylation in cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:2023–2030. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kang HC, Chae JH, Kim BS, et al. Transcription factor CP2 is involved in activating mBMP4 in mouse mesenchymal stem cells. Mol Cells. 2004;17:454–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]