Abstract

A fast and low-cost fabrication process of flexible hanging drop chips for 3D spheroid cultures was proposed by cutting and bonding Parafilm®, a cohesive thermoplastic. The Parafilm® Hanging Drop Chip (PHDC) was assembled by two-layer of Parafilm® sheet with different sizes of holes. The hole on the upper layer of the Parafilm® is smaller than the hole on the bottom layer. The impact of hole size and sample volume on hanging drop formation and 3D spheroid formations in the hanging drop were investigated. The results showed that 20 µL solution on PHDC with a 3 mm hole could form stabile drop and facilitate spheroid formation. The initial cell number determinates the size of the formed spheroids. Exchanging liquid from the upper hole of the PHDC enables the co-culture of two types of cells in one spheroid and drug efficacy testing in hanging drops. The relative expression of cell adhesion and hypoxia-related genes from spheroids in hanging drop and conventional culture plate suggested the relevance of 3D spheroids and in vivo tumor tissue. The economical hanging drop chip can be fabricated without wet chemistry or expensive fabrication equipment, strengthening its application potential in conventional biological laboratories.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12195-020-00660-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: 3D cell culture, Tumor spheroids, Hanging drop, Co-culture, Cohesive thermoplastic, Parafilm®

Introduction

Proper tools are a prerequisite for successfully studying the operating mechanisms of living organisms. The traditional, two-dimensional (2D) cell culture technique is typically used for cell-based assays. Culturing on flat and rigid substrates in a monolayer is a straightforward procedure.22 However, the differences between a 2D monolayer cell culture and cell growth in vivo are significant. For instance, differences in cell morphology, polarity, receptor expression, interactions with the extracellular matrix (ECM), and the overall cellular architecture have been observed between cells grown as 2D monolayers and those grown in vivo.3,4,29 Recently, three-dimensional (3D) cell cultures have attracted tremendous attention in biomedical fields.10 Different strategies, such as forced-floating matrices, scaffold-assisted spheroid formation, and the hanging drop method, have been used.9,18,21,24,26,38 The hanging drop method is a simple method first reported by Kelm et al.20 The hanging drop method’s critical step is the formation of a stable drop on a hydrophobic surface. During 3D spheroid formation in the hanging drop method, the cells aggregate naturally under gravity’s action without adhering to the substrate. Compared with 3D culture in gel, the pros of 3D culture in solution were (i) good repeatability avoiding negative influence of the differences between the batch of hydrogel on the experimental results; (ii) low cost for biology laboratory with limited resources. The cons of 3D culture in solution were it unable to provide mechanical support.14,15 Since this method was first proposed, different hanging drop platforms have been reported. As reported by Theberge et al.,11 by casting a small liquid volume on a hydrophobic surface, drops can spontaneously form due to surface tension. However, solution exchange is not easily achieved. Fang et al. generated hanging drops on a micro-fabricated PDMS membrane.47 Kim et al. developed a BSA-protein-coated paper as a substrate for the formation of hanging drops.31 Recently, the assembly of polymer films to generate hanging drops was reported by Seu et al.32 These successful studies have broadened the technical potential for hanging drops in 3D cell cultures, particularly for spheroid formation. However, wet chemistry-based modification, solvent cytotoxicity, or special microfabrication procedures were involved in these methods, potentially hindering their use in conventional biological laboratories.

Parafilm® is a universal laboratory item, particularly in biological and chemical labs. It has been widely used for sealing experimental vessels to prevent volatilization, pollution, or odor release of reagents. Because of its thermal sensitivity and its elastic and waterproof properties, we have used it as a building block for fast-prototyping microfluidic patterning paper and electrodes.28,37,46 Susanna et al. generated cell patterns on glass and Petri dishes using a Parafilm® template, demonstrating the good cell compatibility of Parafilm®.36 The key features of Parafilm® for the fast prototyping of low-cost, miniaturized devices are its cohesive thermoplastic-enabled fast bonding, waterproof (hydrophobic), and chemically inert (resistant to acid and alkali solutions) properties. Moreover, the grafting of versatile structures on Parafilm® can be achieved with an office paper cutter. This study further investigated the possibility of cutting and bonding Parafilm® -a cohesive thermoplastic towards a 3D cell culture. Because a 3D culture normally requires a few days or even weeks to study the physiology of cell spheroids, it is crucial to ensure that there is an adequate nutrient supply and stability against unexpected, sudden shocks, which can cause drops to fall, spread, and even mix with nearby drops. Thus, an Parafilm® Hanging Drop Chip (PHDC) was proposed. The impact of hole size and sample volume on hanging drop formation were discussed. In addition, the impact of hole size and sample volume on 3D spheroid formations were investigated. The spheroid-formation process was tracked. The potential to co-culture two types of cells in one spheroid was demonstrated. The relative expression of cell adhesion and hypoxia-related genes was examined to prove the relevance of 3D spheroids and in vivo tumor tissue. Finally, the application of spheroids formed on PHDC in drug screening was demonstrated.

Materials and methods

Materials

Human hepatocellular carcinoma cell (HepG2), human prostate cancer (DU 145), human non-small cell lung cancer (A549), human breast cancer cells (MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231) and Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs) were obtained from Cell bank of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). Calcein-AM/PI kit and Dil were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (USA). CYTO-ID® Green long-term cell tracer was obtained from Enzo Life Sciences (USA). BeyoFast™ SYBR Green qPCR Mix (2X), Doxorubicin (DOX), cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) and 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) were from Beyotime Biotechnology (Shanghai, China). Prime Script RT Reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Perfect Real Time) and MiniBEST Universal RNA Extraction Kit were from TaKaRa (Japan). Accutase™ stemcell dissociation reagent and other reagents were acquired from Gibco (USA) unless otherwise indicated. The deionized water was used in all experiments produced by Millipore Q-Grad®1 system (USA).

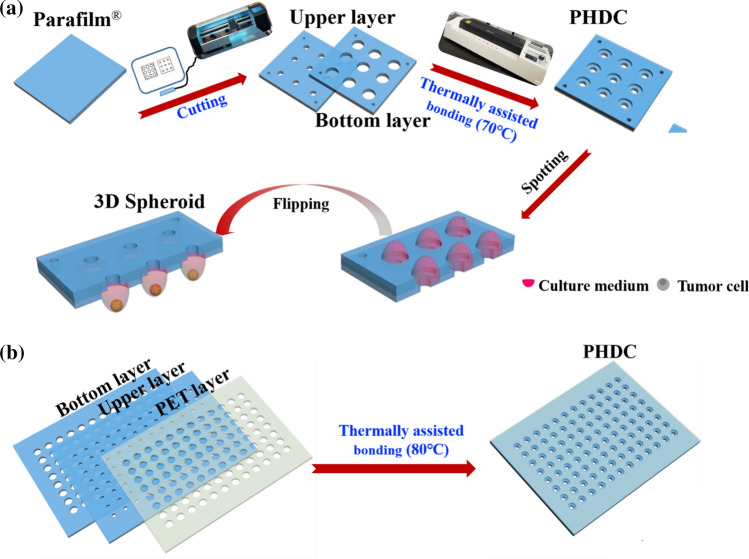

Design and Fabrication of the PHDC

As detailed in Scheme 1, a two-layer chip was designed. The diameters of the upper and bottom layer holes were different. The hole in the upper layer was smaller and designed for adding the solution. The hole on the bottom layer was larger to control the drop size and stabilize the hanging drops. A ring structure could be formed by aligning the hole centers and stacking the two layers of Parafilm®. As shown in Scheme 1a, there are two steps in the PHDC fabrication process. Step 1: A sheet of Parafilm® film was firmed pressed on the crafting board. Then holes with a different diameter on Parafilm® were crafted using a paper crafter (Purcell cutting plotter, model S-500, Shenzhen, China). Step 2: two layers of Parafilm® that were crafted with different holes were laminated together, aligning the holes’ center. Then the two-layer Parafilm® was bonded at 70 °C by a thermal laminator (Deli 3895S, Ningbo, China). The PHDC can be fabricated to use with a standard 96-well and 386-well microplate, which has a 100 mm × 120 mm dimension. However, assembling of two-layer Parafilm® at this size (100 mm × 120 mm) may lack the mechanical stiffness. Thus, a reinforced layer was thermal lamination on the backside of Parafilm® layer (Scheme 1b) to improve its mechanical strength and avoid unexpected deformation of the Parafilm® sheet. In this study, polyethylene terephthalate (PET) film with a thickness of 100 µm was selected as reinforcement material because of its good transparency, tensile strength, and good chemical resistance.25 In detail, holes with the same size on the upper layer of Parafilm® sheet were crafted on the PET sheet. The PET sheet was then thermal bonding with the two-layer Parafilm® assemble by the lamination machine at 80 °C.

Scheme 1.

(a) Schematic representation of the fabrication process of Parafilm® hanging drop chip; (b) adding of Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) film to improve the stability of large area PHDC.

Cell Culture and Spheroids Formation

Cell Preparation

Cells were cultured in DMEM medium with 10% FBS and 1% antibiotic antimycotic (100 units of penicillin, 100 μg streptomycin). A 70%–80% confluent monolayer was washed with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) and harvested by a 0.05% trypsin/0.02% EDTA solution treatment. Live-cell fluorescent dyes were used to stain cells to facilitate their observation and tracing. In this study, tumor cells (HepG2, DU145, A549, MCF-7, and MDA-MB-231) and HUVECs were treated by CYTO-ID® green cell tracer (green) and Dil (red), respectively, according to product instruction. In brief, monolayer growth cells were collected in a 1.5 mL centrifugal tube (106 cell/mL) and washed twice with PBS (pH 7.4). The fluorescence tracer solution (20 μg/mL) was added. The cells were incubated at 37 °C for 10 min and then at 4 °C for 15 min. Then, the stained cells were washed 3 times with PBS (pH 7.4). The fluorescence tracer stained cells were then used for spheroid formation on PHDC.

Tumor Cell Spheroids

20 μL tumor cell suspension was spotted on each hole by using a pipette. Then the PHDC was gently flipped to form a hanging drop. The PHDC was placed in a culture dish and cultured in a cell incubator (5% CO2, 37 °C). Cells in the handing drop were examined under microscopy after 1, 3, 5, and 7 days’ incubation. The cell culture medium was exchanged via the upper holes on PHDC. In this way, 5 μL of the old medium was aspirated and followed by replenishment with 5 μL fresh medium every two days. It is important to note that moderate culture media should be placed in the culture dish to minimize hanging drops’ evaporation. For Corning® ultra-low attachment plate (ULAP), 100 μL tumor cell suspension was added in each well and cultured in cell incubator (5% CO2, 37 °C).

HepG2 Cell and HUVECs Co-Culture Spheroids

10 μL CYTO-ID® green labeled HepG2 cell suspension was firstly dropped on PHDC and flipped to form a hanging drop. After incubation for 24 h, 10 μL Dil labeled HUVECs suspension was added into the HepG2 hanging drop from the upper hole. The cell culture medium was renewed every two days, as described above.

Characterization of Tumor Spheroid

3D Structure of Spheroids

Cells were seeded on PHDC and incubated for 5 days. To facilitate the observation of 3D structure of spheroids under confocal microscopy, the nuclei of cells in hanging drops were stained by DAPI. In brief, 5 μL medium of the hanging drop was replaced with the equal volume of DAPI solution (20 μg/mL) and incubated for 10 min at room temperature. Then spheroids were harvested by centrifugation and then washed by PBS (pH 7.4) three times and characterized on a confocal microscope (LSM 800, Zeiss, Germany) at 364 nm.

Staining of Live/Dead Cells

A working solution containing 4 μM Calcein-AM and 8 μM PI was prepared in PBS (pH 7.4). 5 μL medium of the hanging drop was replaced with an equal volume of working solution and incubated for 1 h. For 2D culture group, 100 μL tumor cells (105 cell/mL) were cultured on 96-well plate for 3 days and 7 days. The cells were then stained in 30 μL live/dead working solution (1 μM Calcein-AM and 2 μM PI) and incubated for 1 h. The stained cells were washed with fresh PBS three times to remove the excess dyes and then imaged using an inverted fluorescence microscope (TS100-F, Nikon, Japan).

Quantitative PCR Analysis

HepG2 spheroids (100 hanging drops) on PHDC were incubated as indicated time, and then harvested for quantitative PCR (qPCR). In brief, total RNA was isolated with the MiniBEST Universal RNA Extraction Kit and quantified by DeNovix®DS-11+ spectrophotometry at 260 nm (DeNovix, USA). Total RNA (500 ng) was reverse transcribed to cDNA using the Prime Script RT Reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Perfect Real Time, TaKaRa, Japan). Then qPCR was run on the QuantStudio™ 3 System (Thermo Fisher, USA) with BeyoFast™ SYBR Green qPCR Mix (2X). qPCR primers for Cadherin 1(CDH 1), Cadherin 2 (CDH 2), Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha (HIF-1α), Hypoxia-inducible factor-2 alpha (HIF-2α), Cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4), Cytochrome P450 1A1 (CYP1A1) and Albumin were designed and validated by the guidelines recommended by the Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR experiments (MIQE) (supplementary information sTable 1).6,42 Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as an internal control. The relative expression levels of each gene in cells were normalized in comparison with the GAPDH gene using the 2−ΔΔCt method. Three independent experiments were performed.

Testing Anti-cancer Drug Efficacy by Using Tumor Spheroids

Doxorubicin (DOX) was used as the model drug in the assay. A series concentration of DOX with concentrations of 50, 100, 200, 400, 800 μM was prepared to treat the cells. Cells grown in 96-well plates were treated as a 2D culture control. First, for 3D spheroids, 20 µL cell suspension (5 × 105 cell/mL) was added on the PHDC to form cell hanging drop and incubated for 3 days. Then, 2 μL medium of the hanging drop was replaced with an equal volume of DOX solution to get the final concertation of DOX (5, 10, 20, 40, and 80 μM). For 2D and 3D control group, 100 µL tumor cells (105 cell/mL) were cultured on 96-well plate or ULAP for 3 days and treated by 100 µL DOX solution. After 48 h of incubation, the spheroids/cells were stained by Calcein-AM/PI and imaged under the microscope (TS100-F, Nikon, Japan). To further quantify the anti-tumor effect of DOX, the live cells were measured by CCK-8 kit. In brief, spheroids in hanging drops were harvested and digested using Accutase stemcell dissociation reagent. Then cells were suspended in 100 μL culture medium and placed into a 96-well plate. Next, CCK-8 reagent was added to the cells at a final concentration of 10% and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. Finally, the absorbance was measured at 450 nm with a reference wavelength of 630 nm by ELx800TM microplate reader (GENE, Hong Kong, China). The cell viability was calculated as the percentage ratio between the absorbance of DOX-treated cells and untreated cells. Three independent experiments were performed.

Statistics Analysis

All experiments were performed three times. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Experiment results were analyzed with the Student’s t-test using Origin Statistic software (OriginLab, USA). P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results and Discussion

Fast Fabrication of Low-Cost PHDC for Hanging Drop Generation

The procedure to fabricate the thermal bonded PHDC is shown at supplementary sFig. 1. The ring structure formed by stacking the two films is shown in Fig. 1a. The thickness of a single pristine Parafilm® film is 120 μm. By the thermally-assisted bonding, the total thickness of the PHDC is 185 ± 5 µm, while the depth of the ring structure is 72 ± 3 μm, which is the neck of the hanging drop (Fig. 1b). It has been reported that the micro-ring can improve the stability of the droplet and prevent its diffusion.16,19 In addition, the diameters of the holes were compared before and after thermal bonding. The cutting and lamination action caused size changes are of less than 3.3%-4.0%. Except for the materials and fabrication procedures’ low costs, the PHDC can be prepared based on various requirements. As shown in Fig. 1c, the PHDC can fit into standard 96- and 384-well plates and a custom-made holder. Because of the soft property of Parafilm®, for 96- and 384-well patterns, a reinforcing PET layer with the same size of the hole can be laminated with the PHDC chip to resist unexpected deformations. The total cost of cutting (desktop cutter) and thermal-bonding (lamination machine) was around $500, which is affordable for most labs. The fabrication can be conducted within 10 min, and no wet-chemistry is involved in the process.

Figure 1.

(a) Microscopy image of micro-rings with different diameters, scale bar: 1 mm; (b) cross-sectional view of the thermal bonded PHDC; (c) different types of PHDCs. In type I, the PHDC was fit into the homemade holder with designed arrays, such as 2 × 4 or 3 × 3. In type II, the PHDC was fit into 96-and 384-well microplates (scale bar: 1 cm); (d) Procedure for culturing 3D spheroids on PHDC. Step I: PHDC was placed on the culture plate. Step II: cell suspensions were introduced in the PHDC. Step III: Hanging drops were formed after inverting the PHDC and were subsequently incubated to promote 3D spheroid formation; (e) diffusion of reagent in the hanging drop with and without pre-existing cells. 5 µL coloring solution was added into the PBS hanging drop from the hole of the PHDC.

Furthermore, one benefit of the proposed PHDC is the simplicity of casting hanging drops. Casting and inversion action was needed to generate hanging drops. As shown in Fig. 1d and supplementary sFig. 2, the PHDC was placed with the larger hole facing up, and the solution was directly cast on the hole. After, the chip was inverted with caution, and a hanging drop formed. Moreover, supplementing the culture medium or adding other reagents into the formed drops could be achieved by pipetting through the hole. The ease of adding culture medium into the formed hanging drop is beneficial for long-term cell culture. The diffusion equilibrium can be achieved quickly in hanging drops, which was determined by observing the diffusion of 0.5 μL of blue food dye in a hanging drop with and without tumor cells (Fig. 1e and supplementary information sVideo1). The fast diffusion equilibrium can prevent a heterogeneous culture environment for drug screening. As summarized in Table 1, comparing with previous hanging drop based spheroids formation methods, the fabrication of PHDCs was straightforward with an office level paper cutter and photo-lamination machine.12,13,27,31,32,44,47 No wet-chemical processes were used to assemble the chips. In addition to the fabrication simplicity, forming spheroids with the PHDC only required casting and inversion. Thus, there are few obstacles to the adoption of this method by biological researchers.

Table 1.

Comparison of handing drop platforms.

| Substrate for hanging drop platform | Surface modification | Sampling | Fabrication time | Solution exchange | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paper | Yes (BSA/UV) | Manual potting | > 10 min | Easy | 31 |

| Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) | Yes (PVC Flake) | Manual potting | > 10 min | – | 32 |

| Polystyrene dish | No | Manual potting | – | Difficult | 12 |

| Polystyrene dish | No | Bioprinting | – | Difficult | 44 |

| Polydimethylsiloxane | No | Injection pump | > 2 h | Easy | 13,27,47 |

| Parafilm® | No | Manual potting | ~ 10 min | Easy | This work |

Optimization of PHDCs for Hanging Drop and Tumor Spheroids Formation

The effects of the hole diameter and solution volume on the sizes of the hanging drops were investigated. PHDCs with different hole sizes at the bottom layer were fabricated. Different volumes of liquid were cast on the holes. The formed hanging drops were imaged on the POWEREACH® contact angle measurement stage. As shown in Fig. 2a, the shapes of the drops were affected by the diameter of the bottom hole. For instance, 20 µL of liquid was added on PHDCs with different hole diameters. When the hole was small (diameter = 3 mm), a hemispherical drop formed. However, when the hole diameter increased to 5 mm, a narrow bump formed instead of a hanging drop. For holes with a 3 mm diameter, when the liquid volume increased from 20 to 60 µL, the height of the drop increased from 2.62 to 4.79 mm, and the stability of the drops decreased. The liquid fell immediately when the volume increased to 70 µL. The results proved that the hole diameter and applied liquid volume determined the shapes and the stabilities of the drops (Fig. 2b). For cell culture experiment, 20 µL solution was added to ensure the stability during the 7-days incubation time.

Figure 2.

(a) Optimization of hanging drop volume with respect to hole diameter (3, 4, and 5 mm; scale bar: 1 mm); (b) height of the hanging drops with respect to different sizes of holes at the bottom Parafilm® layer. (c) The impact of the hanging drop shape on spheroid formation. 20 µL cell suspension was cast on holes with different sizes. ΔP denotes additional pressure on hanging drop (scale bar: 200 μm).

Next, the impact of the hanging drop shape on spheroid formation was investigated. In addition to gravity, we speculated that the formation of the cell spheroid was also due to the hanging drop’s additional pressure because of surface tension. The additional pressure (ΔP) was calculated, using the Young–Laplace formula,8,41

where γ is the surface tension coefficient, and R1 and R2 are the micro-ring radius (half of the diameter) and the height of hanging drop, respectively (Fig. 2c). Experimentally, 20 μL of HepG2 cells were used as a cell model with a density of 5.0 × 103 cell/drop on PHDC, with different diameter holes (3, 4, and 5 mm). As shown in Fig. 2c, the values of ΔP induced by the hanging drops formed, using the 3, 4, and 5 mm holes that were 1.15γ, 0.90γ, and 0.68γ, respectively. The ΔP value of the hanging drop on the 3-mm chip was the largest one. Meanwhile, after 12 h of incubation, cell aggregates were observed in the hanging drops with smaller holes, suggesting that the additional pressure was also an important factor driving 3D spheroids’ formation. In the following experiment, a 3-mm diameter PHDC with a 20 μL cell volume was used for the 3D cell culture.

Formation and Growth Dynamics of the Spheroid in Hanging Drop on PHDC

The dynamic of cell spheroid formation on the PHDC was studied. Experimentally, 20 μL HepG2 cell suspension (5.0 × 105 cell/mL) was cast on the chip. As shown in Fig. 3a, the cells aggregated and formed a sheet-like structure on day 1. The cell sheets subsequently began to coalesce and packed closer (days 2–3). Gradually, the cells aggregated into a spherical shape (days 3 and beyond). In addition, the confocal microscope Z-axis images of cell spheroids stained by DAPI were recorded to depict the 3D nature of spheroids. The confocal images of a typical cell spheroid in a hanging drop on PHDC is shown in supplementary sFig. 3. The Z-axis images’ step length was 80 μm, by which the Z-height of the tumor spheroid could be deduced as 400 μm. Using the same procedure, DU 145 spheroids, A549 spheroid, and MCF-7 spheroid and MDA-MB-231 spheroid were successfully formed on PHDC after 3 day incubation (Supplementary sFig.4).

Figure 3.

(a) Spheroids formation dynamics on PHDC. 20 µL HepG2 cell suspension (5 × 105 cell/mL) was cast on PHDC and cultured for several days (scale bar: 200 μm); (b) image of HepG2 spheroids on PHDC at day 5 formed with different initial cell densities (scale bar: 200 μm); (c) comparison of the average diameters of HepG2 spheroids formed on ultra-low attachment plate (ULAP) and PHDC (n = 3).

Next, the effect of initial cell number on the formation of spheroids was studied. To better track the cell spheroid formation, HepG2 cells were pre-stained using the CYTO-ID® green long-term cell tracer. 20 μL HepG2 cell suspension was added on the 3-mm diameter PHDC. Figure 3b shows the fluorescent images of the cell spheroids formed within the hanging drops after culturing for 5 days. When the initial cell number increased from 1.25 × 103 cell/drop to 10 × 103 cells/drop, the diameters of the formed cell spheroids increased from 264 ± 15 to 705 ± 32 μm (Fig. 3c). The results indicated that the initial loaded cell number mainly determined the sizes of the spheroids. A higher cell density resulted in larger cell spheroids. In addition, PHDCs were compared with conventional 3D culture on Corning® ultra-low attachment plate (ULAP) in 3D spheroid formation. As shown in supplementary sFig. 5, the spheroids formed on PHDC were more uniform compared to those formed in the ULAP. In addition, the same initial cell number formed larger spheroids in PHDC than in the ULAP (Fig. 3c). Apart from the cost of ULAP, the medium volume for each well of the ULAP is 100 µL, while the volume of each hanging drop is 20 µL, suggesting that the PHDC can be a viable alternative to 3D culture dishes in saving of precious clinical biopsy.

Characters of HepG2 Spheroids Formed on PHDCs

Primary liver cancer was the sixth most common malignant tumor worldwide, and the mortality rate was the fourth of the global malignant tumor. The incidence rate of liver cancer was still rising in recent years.5,48 The liver cell spheroids culture has been suggested as a useful technique in liver cancer research.7 HepG2 cells were derived from human hepatoblastoma. It has been widely used for pharmacological and metabolic studies because its biotransformation metabolizing enzymes have homology with normal human liver parenchymal cells.1,30,34 In the following experiment, HepG2 cell was used as a cell model.

The morphological characters of the HepG2 spheroids were investigated. First, the spheroids were examined by Calcein-AM and PI staining, which are specific fluorescent dyes for live and dead cells, respectively. With the increase in incubation time from days 3 to days 7, PI-stained dead cells increase (Fig. 4a). The fluorescent images were further analyzed by the intensity profile of ImageJ (supplementary sFig. 6). Spheroids cultured for 3 days show a relative uniform green fluorescent intensity, while the red fluorescent signal is negligible. However, the spheroids’ intensity profile from the 7-d culture shows a lower green intensity at the center, while a higher red intensity was observed from the spheroid’s center (Fig. 4a and supplementary sFig. 6). The change of fluorescent profile indicates the distribution of live/dead cells in spheroids. In the meantime, the gene expressions of the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1α and HIF-2α) of cells were quantified by qPCR. As shown in Fig. 4b, compared with the 2D-culture HepG2 cells, the HIF-1α and HIF-2α levels in the seventh-day spheroid cells were 11.89 ± 0.99 and 3.16 ± 0.070 times higher than those of the 2D culture, indicating a significant hypoxia-inducible factor expression increase in the spheroids. The changes in HIF-1α and HIF-2α, observed in the spheroids formed in PHDC, were in line with previous studies,17 suggesting PHDC is a reliable, low-cost platform to generate spheroids.

Figure 4.

(a) Live/dead cell distribution in HepG2 cells cultured on tissue culture plate (TCP, 2D) and PHDC (3D). Cells were stained with Calcein-AM (green) and PI (red) for observing of live and dead cells (scale bar: 200 μm); (b) relative mRNA expression of hypoxia-inducible factor in HepG2 spheroids culture on TCP and PHDC analyzed by qPCR; (c) relative mRNA expression of CYP 3A4, CYP 1A1 and Albumin in cells cultured on TCP and PHDC analyzed by qPCR, * denotes p < 0.05, ** denotes p < 0.01.

The cytochrome P450 enzymes and albumin were used as indicators of liver cells’ specific physiological function.2,40,43 CYP3A4 and CYP1A1 belong to the family of cytochrome P450 enzymes and are involved in the metabolism and interaction of endogenous toxic and exogenous toxic substances. As compared in Fig. 4c, the CYP3A4 and CYP1A1 mRNA expressions were higher in 3D HepG2 spheroids than those in tissue culture plate (TCP)-based 2D cultures. The relative expressions of CYP3A4 and CYP1A1 were increased to about 12 ± 0.50-fold and 127 ± 1.3-fold at 7 days-spheroids, respectively. Changes in albumin mRNA, which is closely related to osmotic pressure, nutrition balance, and heavy metals detoxification, were in a similar pattern. Cell spheroids formed on the PHDC show a 4.60 ± 1.60–10.70 ± 1.20-fold increase in albumin’s relative expression from day 3 to day 7. Compared with cells grown on TCP in monolayer, the cell–cell interaction molecules, cadherin CDH1 and CDH2,33 gradually increased from the third day, indicating a more vital cell–cell interaction between cells in spheroids (supplementary information sFig. 7). The difference between 3D spheroids and 2D monolayer cell sheets in hypoxia-induced factor, cadherin, and the liver functional-related molecules (CYP3A4, CYP1A1, and albumin) suggested that HepG2 spheroids formed on PHDC could better mimic a solid tumor than monolayer cultured cells.

Application of PHDCs in Drug Testing

Benefiting from the flexible operation ability of the hanging drop system, we further applied PHDC to generate spheroids as a 3D model for drug screening. Because the solution could be supplied through the top side of the PHDCs, the anti-tumor reagents could be added into the drops at different stages for testing the therapeutic effects. DOX, an RNA and DNA synthesis inhibitor commonly used in clinical practice, was studied as a drug model. First, the effect of DOX on spheroids was characterized by tracing the size of the spheroids. As shown in Fig. 5a, the diameter of HepG2 spheroids decreases gradually upon DOX treatment. Increased cell debris can be observed around the spheroids. In addition, live cell distribution in spheroid under DOX treatment was characterized. Apart from size shrinking, the live cells (green intensity) decrease along with the increase of drug concentration, while an increase of dead cells (red intensity) was witnessed (Fig. 5a). The morphology change of the spheroids indicates that DOX can inhibit the growth of 3D spheroids. Next, drug efficacy on cells cultured in different models (3D/cell spheroids on PHDC vs. 2D/cells grown on a 96-well micro-plate) were compared. Specifically, DOX-treated spheroids in hanging drops were harvested and dissociated into cell suspension for CCK-8 assay. The results showed that the viable cells in HepG2 spheroids (Fig. 5b) were higher than those of the 2D HepG2 cell sheets (supplementary sFig. 8) upon the same DOX concentration. In addition, Fig. 5b shows the cell survival rate of different-sized tumor spheroids treated with the same concentration of DOX. The smaller the tumor spheroids was, the lower the cell survival rate, indicating that smaller tumors were more sensitive to DOX treatment. Previous studies suggest that tumor size is an essential chemotherapy parameter with larger tumors being less responsive to treatment.35 In addition, the HepG2 cells (100 μL per well, 105 cell/mL) were cultured in ultra-low attachment culture plate for 3 days and tested drug efficacy by CCK-8. The results show that the cell survival rate of HepG2 cells cultured in ULAP is lower than those grown in PHDC (Supplementary sFig. 9). For in vitro cell assay, it has been argued that comparing to 2D monolayer cells, 3D spheroids possess a dense structure with tight junctions (e.g., cell–cell interaction) prevents the drug reaching the cells at the central area of the spheroids.39,45

Figure 5.

Application of PHDC on drug efficacy testing. (a) Microscopic images of HepG2 spheroids treated by DOX. Cells were stained with Calcein-AM (green) and PI (red) for observing of live and dead cells (scale bar: 200 μm); (b) viability of HepG2 cells cultured in 2D (96-well microplate) and 3D (spheroids on PHDC).

Application of PHDCs in the Formation of Heterogeneous Spheroids: Co-Culture of HepG2 and HUVECs

More than one type of cell is in a solid tumor in a live body.23 For example, to support tumor cell growth, angiogenesis (blood vessel formation) occurs in solid tumors. As illustrated in Fig. 2b, a solution can be added to the formed hanging drops, providing the chance to investigate cell–cell co-cultures in the spheroids. We studied the co-culture of the blood vessel cells (HUVECs) and tumor cells (HepG2). First, a CYTO-ID® labeled HepG2 cell (green) suspension was added to form a hanging drop (104 cell/drop). Then, different numbers of Dil labeled HUVECs (red) were added into the HepG2 spheroids. The number ratios of HUVECs: HepG2 were 0.5:1, 1:1, and 2:1. As shown in Fig. 6a, the HepG2 and HUVECs cells spontaneously self-assembled without supporting material. The spontaneously formed co-spheroids’ sizes increased as the HUVEC cell numbers and overall total number (HepG2 plus HUVECs) increased. With prolonged incubation time, the co-culture spheroids’ sizes increased as well (Fig. 6b). From the fluorescent image (Fig. 6c), the distributions of cells within the spheroids could also be distinguished. The tumor cells (green) preferred to form aggregates (spheroids), while the HUVECs (red) decorated the HepG2 aggregates, suggesting that the cells had different growth patterns. The heterogeneous cell spheroids formed on PHDC suggest this easy operations platform can be used to investigate cell–cell interaction.

Figure 6.

Application of PHDC on co-culture cell spheroids formation. (a) Representative microscopic images of co-culture spheroids with different initial seeding density (HepG2: HUVECs ratio = 1:0.5, 1:1 and 1:2) (Green: HepG2 cells, red: HUVECs, scale bars: 200 μm); (b) average diameters of co-culture spheroids formed on PHDC over time; (c) distribution of cells in the co-culture spheroid (scale bars: 200 μm).

Conclusions

We developed a novel Parafilm®-based hanging drop system for 3D spheroid cultures by cutting and bonding cohesive thermoplastic. The sample volume and hole structure were optimized to increase efficiency of spheroids formation. Successfully formatting of spheroids from multiple tumor cell lines indicated the feasibility of the platform in fast generating tumor spheroids. Studies of spheroid formation dynamics, cell physiological conditions within the spheroids, and drug sensitivity proved that the spheroids formed on the PHDC can better reflect the physiology characters of liver than 2D cultured cells. The ease of fabrication, operation, and liquid handling with the PHDCs provides a low-cost alternative for biological laboratories to investigate 3D cell spheroids.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31872753 and 11702047), the China Scholarship Council (No. 201906995004), Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing (cstc2019jcyj-msxmX0211), Applied Basic Research Program of Sichuan Province (19YJC0975, 2018GZYZF0008), and Chongqing Engineering Research Center for Micro-Nano Biomedical Materials and Devices.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ling Yu, Email: lingyu12@swu.edu.cn.

Chang Ming Li, Email: ecmli@swu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Aden DP, Fogel A, Plotkin SA, Damjanov I, Knowles BB. Controlled synthesis of HBsAg in a differentiated human liver carcinoma-derived cell line. Nature. 1979;282:615–616. doi: 10.1038/282615a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baldwin SP, Saltzman WM. Aggregation enhances catecholamine secretion in cultured cells. Tissue Eng. 2001;7:179–190. doi: 10.1089/107632701300062796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhadriraju K, Chen CS. Engineering cellular microenvironments to improve cell-based drug testing. Drug Discov. Today. 2002;7:612–620. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(02)02273-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birgersdotter A, Sandberg R, Ernberg I. Gene expression perturbation in vitro—a growing case for three-dimensional (3D) culture systems. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2005;15:405–412. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bray FI, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2018;68(2018):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bustin SA, Benes V, Garson JA, Hellemans J, Huggett J, Kubista M, Mueller R, Nolan T, Pfaffl MW, Shipley GL, Vandesompele J, Wittwer CT. The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin. Chem. 2009;55:611–622. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.112797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang TT, Hughes-Fulford M. Monolayer and spheroid culture of human liver hepatocellular carcinoma cell line cells demonstrate distinct global gene expression patterns and functional phenotypes. Tissue Eng. Part A. 2009;15:559–567. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2007.0434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen T, Chiu MS, Weng CN. Derivation of the generalized Young-Laplace equation of curved interfaces in nanoscaled solids. J. Appl. Phys. 2006;100:074308. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen G, Xu R, Zhang C, Lv YG. Responses of MSCs to 3D scaffold matrix mechanical properties under oscillatory perfusion culture. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2017;9:1207–1218. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b10745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Costa EC, Moreira AF, Diogo DM, Gaspar VM, Carvalho MP, Correia IJ. 3D tumor spheroids: an overview on the tools and techniques used for their analysis. Biotechnol. Adv. 2016;34:1427–1441. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2016.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Groot TE, Veserat KS, Berthier E, Beebe DJ, Theberge AB. Surface-tension driven open microfluidic platform for hanging droplet culture. Lab Chip. 2016;16:334–344. doi: 10.1039/c5lc01353d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foty R. A simple hanging drop cell culture protocol for generation of 3D spheroids. J. Vis. Exp. 2011;51:e2720. doi: 10.3791/2720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frey O, Misun PM, Fluri DA, Hierlemann JGHA. Reconfigurable microfluidic hanging drop network for multi-tissue interaction and analysis. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:4250. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heywood HK, Sembi PK, Lee DA, Bader DL. Cellular utilization determines viability and matrix distribution profiles in chondrocyte-seeded alginate constructs. Tissue. Eng. 2004;10:1467–1479. doi: 10.1089/ten.2004.10.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirschhaeuser F, Menne H, Dittfeld C, West J, Muellerklieser W, Kunzschughart LA. Multicellular tumor spheroids: an underestimated tool is catching up again. J. Biotechnol. 2010;148:3–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsiao AY, Tung YC, Kuo CH, Mosadegh B, Bedenis R, Pienta KJ, Takayama S. Micro-ring structures stabilize microdroplets to enable long term spheroid culture in 384 hanging drop array plates. Biomed. Microdevices. 2012;14:313–323. doi: 10.1007/s10544-011-9608-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu CJ, Wang LY, Chodosh LA, Keith B, Simon MC. Differential roles of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) and HIF-2α in hypoxic gene regulation. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;24:9361–9374. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.24.9361-9374.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ivascu M, Kubbies J. Rapid generation of single-tumor spheroids for high-throughput cell function and toxicity analysis. Biomol. Screen. 2006;11:922–932. doi: 10.1177/1087057106292763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalinin Y, Berejnov V, Thorne RE. Controlling microdrop shape and position for biotechnology using micropatterned rings. Microfluid. Nanofluid. 2008;4:449–454. doi: 10.1007/s10404-008-0272-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelm JM, Timmins NE, Brown CJ, Fussenegger M, Nielsen LK. Method for generation of homogeneous multicellular tumor spheroids applicable to a wide variety of cell types. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2003;83:173–180. doi: 10.1002/bit.10655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kleinman HK, Martin GR. Matrigel: basement membrane matrix with biological activity. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2005;15:378–386. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knight E, Przyborski S. Advances in 3D cell culture technologies enabling tissue-like structures to be created in vitro. J. Anat. 2015;227:746–756. doi: 10.1111/joa.12257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuo CT, Wang JY, Lin YF, Wo AM, Chen BP, Lee H. Spatial variations in the molecular diversity of dissolved organic matter in water moving through a boreal forest in eastern Finland. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:4363–4373. doi: 10.1038/srep42102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee J, Cuddihy MJ, Cater GM, Kotov NA. Engineering liver tissue spheroids with inverted colloidal crystal scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2009;30:4687–4694. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levchik GF, Grigoriev YV. Phosphorus–nitrogen containing fire retardants or poly (butylene terephthalate) Polym. Int. 2000;49:1095–1100. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin RZ, Chang HY. Recent advances in three-dimensional multicellular spheroid culture for biomedical research. Biotechnol. J. 2008;3:1172–1184. doi: 10.1002/biot.200700228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu W, Sun M, Lu B, Yan M, Han K, Wang J. A microfluidic platform for multi-size 3D tumor culture, monitoring and drug resistance testing. Sens. Actuators, B. 2019;292:111–120. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu Y, Shi ZZ, Yu L, Li CM. Fast prototyping of a customized microfluidic device in a non-clean-room setting by cutting and laminating Parafilm®. RSC Adv. 2016;6:85468–85472. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu H, Stenzel MH. Multicellular tumor spheroids (MCTS) as a 3D in vitro evaluation tool of nanoparticles. Small. 2018;13:1702858. doi: 10.1002/smll.201702858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mazaris EM, Roussos CT, Papalois VE. Hepato-cyte transplantation: a review of worldwide clinical developments and experiences. Exp. Clin. Transplant. 2005;3:306–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Michael IJ, Kumar S, Oh JM, Kim D, Kim J, Cho Y-K. Surface-Engineered Paper Hanging Drop Chip for 3D Spheroid Culture and Analysis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2018;10:33839–33846. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b08778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oliveira MB, Neto AI, Correia CR, Rial-Hermida MI, Lorenzo CA, Mano JF. Superhydrophobic chips for cell spheroids high-throughput generation and drug screening. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2014;6:9488–9495. doi: 10.1021/am5018607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ong S-M, Zhao Z, Arooz T, Zhao D, Zhang S, Du T, Wasser M, van Noort D, Yu H. Engineering a scaffold-free 3D tumor model for in vitro drug penetration studies. Biomaterials. 2010;31:1180–1190. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park JK, Lee DH. Bioartificial liver systems: current status and future perspective. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2005;99:311–319. doi: 10.1263/jbb.99.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ran R, Wang HF, Hou F, Liu Y, Hui Y, Petrovsky N, Zhang F, Zhao C-X. A microfluidic tumor-on-a-chip for assessing multifunctional liposomes tumor targeting and anticancer efficacy. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2019;8:1900015. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201900015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rydholm S, Rogers RA, Brismar H. Parafilm dependent cell patterning. Microsc. Microanal. 2005;11:1174–1175. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shi ZZ, Wu XS, Lu Y, Lu ZS, Li CM, Yu L. Fast and low-cost patterning of electrodes on versatile 2D and 3D substrates by cutting and origami cohesive thermoplastic for biosensing applications. Sensors Actuators B. 2018;255:2431–2436. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sourla C, Doillon MK. Three-dimensional type I collagen gel system containing MG-63 osteoblasts-like cells as a model for studying local bone reaction caused by metastatic cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 1996;16:2773–2780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tung YC, Hsiao AY, Allen SG, Torisawa Y, Hoc M. S, Takayama, High-throughput 3D spheroid culture and drug testing using a 384 hanging drop array. Analyst. 2011;136:473–478. doi: 10.1039/c0an00609b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verma P, Verma V, Ray P, Ray AR. Agar-gelatin hybrid sponge induced three dimensional in vitro ‘liver-like’ HepG2 spheroids for the evaluation of drug cytotoxicity. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2009;3:368–376. doi: 10.1002/term.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang GF. Effects of surface elasticity and residual surface tension on the natural frequency of microbeams. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007;90:231904. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang LX, Zhou Y, Fu JJ, Lu ZS, Yu L. Separation and characterization of prostate cancer cell subtype according to their motility using a multi-layer CiGiP culture. Micromachine. 2018;9:660. doi: 10.3390/mi9120660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Westerink WMA, Schoonen WGEJ. Cytochrome p450 enzyme levels in HepG2 cells and cryopreserved primary human hepatocytes and their induction in HepG2 cells. Toxicol. In Vitro. 2007;21:1581–1591. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu F, Sridharan B, Wang SQ, Gurkan UA, Syverud B, Demirci U. Embryonic stem cell bioprinting for uniform and controlled size embryoid body formation. Biomicrofluidics. 2011;5:022207. doi: 10.1063/1.3580752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yip D, Cho CH. A multicellular 3D heterospheroid model of liver tumor and stromal cells in collagen gel for anti-cancer drug testing. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013;433:327–332. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu L, Shi ZZ. Microfluidic paper-based analytical devices fabricated by low-cost photolithography and embossing of Parafilm®. Lab Chip. 2015;15:1642–1645. doi: 10.1039/c5lc00044k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao SP, Ma Y, Lou Q, Zhu H, Yang B, Fang Q. Three-dimensional cell culture and drug testing in a microfluidic sidewall-attached droplet array. Anal. Chem. 2017;19:10153–10157. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b02267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zheng RS, Zhang HM. Estimates of cancer incidence and mortality in China. Chin J Cancer. 2013;36:384–389. doi: 10.1186/s40880-017-0234-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.