Abstract

Introduction

The outbreak of COVID-19 disrupted lives across the United States. Evidence shows that such a climate is deleterious to mental health and may increase demand for mental health services in emergency departments. The purpose of this study was to determine the difference in emergency department utilization for mental health diagnoses before and after the COVID-19 surge.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study between January–August 2019 and January–August 2020 with emergency department encounter as the sampling unit. The primary outcome was the proportion of all emergency department encounters attributed to mental health. We performed chi-square analyses to evaluate the differences between 2019 and 2020.

Results

We found that overall emergency department volume declined between 2019 and 2020, while the proportion attributable to mental health conditions increased (p < 0.01). Substance abuse, anxiety, and mood disorders accounted for nearly 90% of mental health diagnoses during both periods. When stratified by sex, substance abuse was the leading mental health diagnosis for males and anxiety and substance abuse disorders combined accounted for the largest proportion for females.

Discussion

The emergency department is an important community resource for the identification and triage of mental health emergencies. This role is even more important during disasters and extended crises, making it imperative that emergency departments employ experienced mental health staff. This study provides a comparison of emergency department utilization for mental health diagnoses before the pandemic and during the spring 2020 surge and may serve as a useful guide for hospitals, health systems and communities in future planning.

Keywords: Emergency service, Hospital, Mental health, COVID-19, Mental health services

1. Introduction

The outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) in early 2020 significantly disrupted lives across the United States [1]. Within weeks of the first reported case, schools, shops, restaurants, and workplaces were closed for business, 15% of adults were unemployed, and social distancing and stay-at-home guidelines led to widespread isolation [2]. Evidence shows that such a climate is deleterious to mental health [[3], [4], [5], [6]]. Investigators found COVID-19 associated with higher levels of psychiatric distress, increased prevalence of substance use disorders, relapse, and overdose, and increased use of emergency medical services (EMS) for mental health conditions [[7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13]].

Historically, the emergency department (ED) has served as a conduit for mental health services in the absence of established outpatient care [14]. Though some evidence demonstrates any ED utilization fell as a result of the pandemic, it also shows that the proportion of ED utilization attributed to mental health increased [9,11,15]. An increase in ED utilization for mental health care requires a shift in staffing, training, and relationships with referral services in the ED [16]. It is important for institutional and community stakeholders to examine the scope of ED utilization for mental health conditions during times of crisis, particularly those that exist for an extended length of time.

The primary objective of this study was to determine the difference in ED utilization for mental health conditions before and after the COVID-19 surge in a large, suburban healthcare system. We hypothesized there would be a statistically significant increase in the proportion of ED visits attributed to mental health conditions between 2019 and 2020, and that this would hold across sexes. We also sought to characterize specific types of mental health conditions between the two years to determine the impact of COVID-19 on specific categories of mental health.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and setting

We conducted a cross-sectional study to determine the difference in the proportion of ED encounters attributed to mental health conditions between January–August 2019 and January–August 2020. We utilized master patient index (MPI) data, a combination of clinical, financial, and administrative records, to generate a de-identified sample from three acute care hospitals in southwestern Connecticut. Two of the hospitals are accredited trauma centers and house 137 ED beds collectively (range 15–67). The study was exempt from IRB review as determined by the Biomedical Research Alliance of New York (BRANY) Institutional Review Board.

2.2. Participants

We included all encounters of individuals 18 years and older that sought medical care in the ED during the specified periods of 2019 and 2020. We used the ED encounter as our sampling unit rather than the individual patient and included patients more than once if they utilized the ED multiple times during the study period. We excluded encounters that did not include an ICD-10 code for the primary, secondary, or tertiary diagnosis.

2.3. Variables

The primary outcome of interest was the proportion of all ED encounters attributed to mental health conditions. We created two unique variables to capture this information based on existing frameworks from the World Health Organization's International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) and the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) [17,18]. The first variable reflected any mental health diagnosis, defined as an ED encounter with a mental health, self-injury, suicidal ideation, or substance use disorder ICD-10 code as the primary, secondary, and/or tertiary diagnosis (Supplemental Table S1). We selected these codes from among F01-F99, S00-T88, R00-R99, and V00-Y99 codes [18]. We created a second variable to reflect a primary mental health diagnosis, defined as any mental health, self-injury, suicidal ideation, or substance use disorder ICD-10 code listed as the primary diagnosis.

Our secondary outcome of interest was the distribution of ED encounters by specific mental health category. We stratified mental health conditions per the DSM-5 given the primary ICD-10 diagnosis code [19]. We categorized encounters by the secondary or tertiary ICD-10 code if they did not have a primary mental health diagnosis. These categories included anxiety, mood, substance use, eating, personality, or psychotic disorders, risk of harm to self, and risk of harm to others. We also created a category for other mental health disorders to account for diagnoses otherwise unspecified.

We also collected demographic variables including age, sex, and race. We included age as a continuous variable and race and sex as categorical variables. Race was categorized as white, black, Hispanic, and other (including American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, Indian (of India), or declined to specify).

2.4. Statistical methods

We used SPSS Statistics 27 to conduct all analyses (IBM, Armonk, New York). We did not have any missing data to account for, and we computed descriptive statistics for each of our demographic variables. We performed chi-square analyses to evaluate the difference in the proportion of ED encounters related to mental health between 2019 and 2020 in both the full sample and stratified by sex. We further stratified mental health utilization by month and assessed trends in utilization before, during, and after the first COVID-19 surge in Connecticut (March–May 2020). Lastly, we used descriptive statistics to assess the distribution of mental health conditions by category for both 2019 and 2020 in the full sample and stratified by sex. For hypothesis testing, we specified p < 0.05 as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

This study included 129,429 ED encounters across three hospitals in southwestern Connecticut, with more than half (56.1%) occurring in 2019 (Table 1 ). We excluded 150 encounters due to missing ICD-10 codes. The mean age was 54.4 years old (standard deviation = 21.2), and the majority of encounters took place among female (53.3%) and white (68.3%) patients.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of encounters in the emergency department of three southwestern Connecticut hospitals between January–August 2019 and January–August 2020.

| Emergency department encounters |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic |

Full Sample |

2019 |

2020 |

| Total | 129,429 | 72,592 | 56,837 |

| Age [mean (SD)] | 54.4 (21.2) | 54.5 (21.3) | 54.5 (21.1) |

| Sex [n (%)] | |||

| Female | 69,018 (53.3) | 39,307 (54.1) | 29,711 (52.3) |

| Male | 60,411 (46.7) | 33,285 (45.9) | 27,126 (47.7) |

| Race/Ethnicity [n (%)] | |||

| White | 88,373 (68.3) | 50,064 (69.0) | 38,309 (67.4) |

| Hispanic | 22,401 (17.3) | 12,055 (16.6) | 10,346 (18.2) |

| Black/African American | 12,634 (9.8) | 7211 (9.9) | 5423 (9.5) |

| Othera | 6021 (4.6) | 3262 (4.5) | 2759 (4.9) |

Note: SD = standard deviation, n = number of encounters, % = percent of column total.

Includes Asian, Indian (of India), American Indian/Alaskan Native, Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and unknown/declined to specify.

3.2. Overall ED utilization for mental health

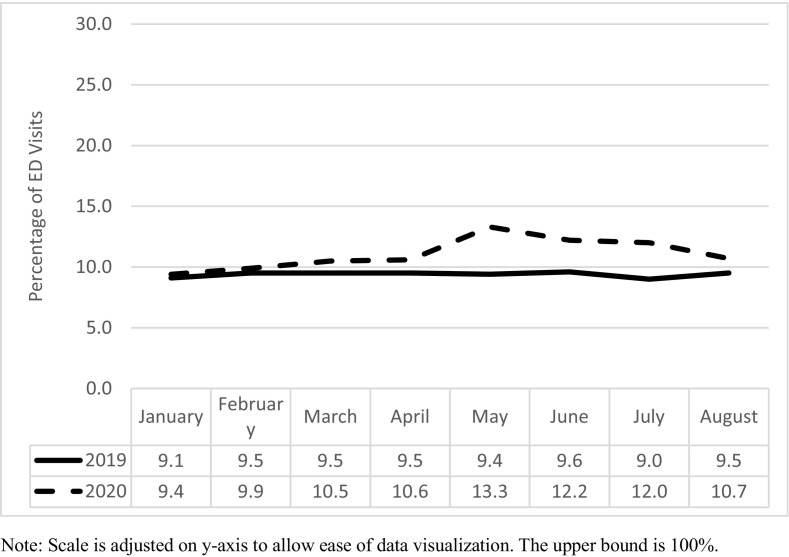

We found the proportion of ED encounters in 2020 with any mental health diagnosis was significantly higher than in 2019 (p < 0.01; Table 2 ). Similarly, the proportion of ED encounters in 2020 with a primary diagnosis code indicating a mental health condition was significantly higher than in 2019 (p < 0.01). The most common mental health conditions were alcohol abuse with intoxication (F10.129), anxiety disorder, unspecified (F41.9), and alcohol use, unspecified with intoxication, unspecified (F.10.929; Supplemental Table S2). ED utilization for any mental health diagnosis remained consistent from January through August 2019 (~9%; Fig. 1 ). However, in 2020, ED utilization for any mental health diagnosis increased in the months following the initial COVID-19 surge, most notably in May (13.3%). Of note, Connecticut did not issue stay at home orders until mid-March 2020. Any increase in ED utilization for mental health prior to this time is less likely to be attributed to COVID-19.

Table 2.

Differences in the proportion of encounters for mental health conditions in the emergency department of three southwestern Connecticut hospitals between January–August 2019 and January–August 2020.

| Total | 2019 | 2020 | χ2, p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Full Sample | ||||

| Total | 129,429 | 72,592 | 56,837 | |

| Any mental health diagnosis | 13,039 (10.0) | 6809 (9.4) | 6230 (11.0) | 87.9, <0.01 |

| Primary mental health diagnosis | 8925 (6.9) | 4762 (6.6) | 4163 (7.3) | 29.0, <0.01 |

| Male | ||||

| Total | 60,411 | 33,285 | 27,126 | |

| Any mental health diagnosis | 7416 (12.3) | 3834 (11.5) | 3582 (13.2) | 39.5, <0.01 |

| Primary mental health diagnosis | 5433 (9.0) | 2848 (8.6) | 2585 (9.5) | 17.3, <0.01 |

| Female | ||||

| Total | 69,018 | 39,307 | 29,711 | |

| Any mental health diagnosis | 5623 (8.1) | 2975 (7.6) | 1914 (4.9) | 40.8, <0.01 |

| Primary mental health diagnosis | 3492 (5.1) | 2648 (8.9) | 1578 (5.3) | 6.9, <0.01 |

Fig. 1.

Emergency department utilization for mental health conditions at three southwestern Connecticut hospitals between January–August 2019 and January–August 2020.

Note: Scale is adjusted on y-axis to allow ease of data visualization. The upper bound is 100%.

The proportion of ED encounters attributed to mental health conditions was higher among males than females in 2019 and 2020 (Table 2). Approximately 12.3% of encounters among males were mental health related (i.e. any mental health diagnosis), while only 8.1% of encounters among females were mental health related. There were statistically significant differences in the proportion of females with any and primary mental health diagnoses in 2020 compared to 2019 (p < 0.01). The findings were similar in males, with a significantly greater proportion of ED encounters attributed to mental health in 2020 compared to 2019 (Table 2).

3.3. ED utilization by mental health category

We found that substance use disorders (~49%), anxiety disorders (~25%), and mood disorders (~15%) accounted for the majority of all mental health-related ED encounters in the study period (Table 3 ). Of note, the distribution of mental health encounters differed between males and females. Anxiety and substance use disorders together accounted for the largest proportion of mental health encounters among females in 2019 and 2020, while substance use disorders alone accounted for the largest proportion of mental health encounters in males (Table 3). The distribution of mental health encounters did not differ dramatically over time across sexes. Substance use disorders held steady for males at approximately 61% in both 2019 and 2020.

Table 3.

Distribution of encounters coded with any mental health diagnosis in the emergency department of three southwestern Connecticut hospitals by sex and year.

| Mental health category | Full sample | Male | Female | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 | |

| Total | 6809 | 6230 | 3834 | 3582 | 2975 | 2648 |

| Mood disorders | 1084 (15.9) | 848 (13.6) | 487 (12.7) | 373 (10.4) | 597 (20.1) | 475 (17.9) |

| Anxiety disorders | 1623 (23.8) | 1570 (25.2) | 619 (16.2) | 592 (16.5) | 1004 (33.8) | 978 (36.9) |

| Substance use disorders | 3306 (48.6) | 3067 (49.2) | 2349 (61.3) | 2208 (61.6) | 957 (32.2) | 859 (32.4) |

| Personality disorders | 78 (1.1) | 63 (1.0) | 33 (0.9) | 27 (0.8) | 45 (1.5) | 36 (1.4) |

| Psychosis/psychotic disorders | 447 (6.6) | 392 (6.3) | 233 (6.1) | 247 (6.9) | 214 (7.2) | 145 (5.5) |

| Risk of harm to others | 5 (0.1) | 1 (0.0) | 5 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) |

| Risk of harm to self | 198 (2.9) | 215 (3.4) | 92 (2.4) | 105 (2.9) | 106 (3.5) | 110 (4.2) |

| Eating disorders | 10 (0.1) | 19 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.1) | 10 (0.3) | 16 (0.6) |

| Other mental health disorders | 58 (0.8) | 55 (0.9) | 16 (0.4) | 27 (0.8) | 42 (1.4) | 28 (1.1) |

Note: data are n (%).

4. Discussion

The primary objective of this study was to describe ED utilization for mental health conditions in a healthcare network in southwestern Connecticut. We hypothesized that the COVID-19 pandemic increased the demand for mental health care in the ED and sought to provide details on the trends seen in this population.

We found that whereas overall ED volume declined between 2019 and 2020, the proportion attributable to mental health conditions increased. Further, the increase occurred during the months following the surge of COVID-19 in Connecticut (i.e. March–May 2020). This is consistent with findings from other countries that showed an increase in ED utilization for self-harm and overdose, as well as anxiety and panic attacks [9,11]. However, other studies within the northeast United States found decreased use of psychiatric emergency services between March and May 2020 [20]. This is likely a reflection of individual hospital's relationships in the community, outpatient services available, as well as characteristics of the communities served. Further work is needed to generalize the impact of COVID-19 on those seeking mental health care at both state and nationals level to help guide policymaking. In the meantime, key stakeholders can use this information to identify needs specific to their emergency departments and communities.

We also explored differences in the types of mental health diagnoses across the two periods to determine any changes in the distribution in our population. This information is important, as a marked change in the type of mental health conditions may require a shift in training, staffing, and referrals to outpatient services. Overall, the distribution remained much the same, with females more likely to seek care for anxiety and substance use disorders and males for substance use disorders alone. These findings are largely consistent with existing literature. A study of ED utilization in the United States found the odds of males presenting for substance-related diagnoses only was 2.75 times that of females [16]. Additionally, there are noted differences in the prevalence of anxiety disorders across sexes [21,22].

Finally, suicidal ideation, one of the top ten occurring ICD-10 codes in our sample, increased slightly between 2019 and 2020. Socioeconomic consequences of the pandemic, including increases in unemployment and homelessness, as well as psychological factors from long-term isolation and sudden bereavement, are concerning risk factors for death by suicide [23,24]. Our finding indicates a need for additional research regarding the impact of COVID-19 on rates of death by suicide or suicidal ideation.

4.1. Limitations

We conducted this study with a limited sample population from one geographic area of the United States. It is likely that other factors in our region contributed to ED utilization that may be different from other locations in the United States. Our results should be generalized only to similar populations. Additionally, we did not explore relationships between variables beyond crude associations among demographics. Further studies are needed to more robustly explore ED utilization for mental health conditions across the many layers of the social-ecological model. Lastly, while COVID-19 is a significant enough event to drive changes in mental health and ED utilization, we cannot rule out other reasons for the marked increase.

4.2. Conclusions

Emergency departments have become de facto sites for the identification and triage of mental health emergencies. This role is even more important during disasters and extended crises, making it imperative that EDs employ experienced mental health staff. This study provides a comparison of ED utilization, including mental health diagnosis distribution overall and by sex, before the pandemic and during the spring 2020 surge and may serve as a useful guide for hospitals, health systems and communities in future planning.

Funding

None.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the technical assistance of Samantha Moffett, MPH in creating the outcome variables of interest and Deborah Geambazi, RN, BSN for providing the data used in this manuscript. We are also grateful to the RobyDodd Family Charitable Foundation, Inc. for their support of a Women's Health Research Scholar who contributed to the work for this manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2021.03.084.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplemental Table 1 - Crosswalk of ICD-10 codes and DSM-5 mental health disorder categories used in study

References

- 1.Huang D., Lian X., Song F., et al. Clinical features of severe patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(9):576. doi: 10.21037/atm-20-2124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bick A., Blandin A. Real-time labor market estimates during the 2020 coronavirus outbreak. SSRN. 2020 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3692425. (Published online September 14) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kposawa A.J. Unemployment and suicide: a cohort analysis of social factors predicting suicide in the US National Longitudinal Mortality Study. Psychol Med. 2001;31(1):127–138. doi: 10.1017/S0033291799002925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marroquin B., Vine V., Morgan R. Mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: Effects of stay-at-home policies, social distancing behavior, and social resources. Psychiatry Res. 2020;293 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pfefferbaum B., Schonfeld D., Flynn B.W., et al. The H1N1 crisis: A case study of the integration of mental and behavioral health in public health crises. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2012;6(1):67–71. doi: 10.1001/dmp.2012.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sher L. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on suicide rates. QJM. 2020;113(10):707–712. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcaa202. (1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alexander G.C., Stoller K.B., Haffajee R.L., Saloner B. An epidemic in the midst of a pandemic: Opioid use disorder and COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.7326/M20-1141. (Published online July 7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Becker W.C., Fiellin D.A. When epidemics collide: Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and the opioid crisis. Ann Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.7326/M20-1210. (Published online July 7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dragovic M., Pascu V., Hall T., Ingram J., Waters F. Emergency department mental health presentations before and during the COVID-19 outbreak in Western Australia. Australas Psychiatry. 2020;28(6):627–631. doi: 10.1177/1039856220960673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holingue C., Kalb L.G., Riehm K.E., et al. Mental distress in the United States at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(11):1628–1634. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joyce L.R., Richardson S.K., McCombie A., Hamilton G.J., Ardagh M.W. Mental health presentations to Christchurch hospital emergency department during COVID-19 lockdown. Emerg Med Australas. 2020 doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.13667. (Published online November 9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rajkumar R.P. COVID-19 and mental health: A review of the existing literature. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;52 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slavova S., Rock P., Bush H.M., Quesinberry D., Walsh S.L. Signal of increased opioid overdose during COVID-19 from emergency medical services data. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;214 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weiss A.J., Barrett M.L., Heslin K.C., Stocks C.C. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2016. Trends in emergency department visits involving mental and substance use disorders, 2006–2013; pp. 1–13.https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb216-Mental-Substance-Use-Disorder-ED-Visit-Trends.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hartnett K., Kite-Powell A., DeVies J., et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on emergency department visits—United States, January 1, 2019–May 30, 2020. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(23):699–704. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6923e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Theriault K.M., Rosenheck R.A., Rhee T.G. Increasing Emergency Department visits for mental health conditions in the United States. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(5) doi: 10.4088/JCP.20m13241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clark L.A., Cuthbert B., Lewis-Fernández R., Narrow W.E., Reed G.M. Three approaches to understanding and classifying mental disorder: ICD-11, DSM-5, and the National Institute of Mental Health’s Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2017;18(2):72–145. doi: 10.1177/1529100617727266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization . 2016. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Psychiatric Association . 5th ed. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldenberg M.N., Parwani V. Psychiatric emergency department volume during Covid-19 pandemic. Am J Emerg Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.05.088. (Published online June). S0735675720304502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bahrami F., Yousefi N. Females are more anxious than males: A metacognitive perspective. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2011;5(2):83–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McLean C.P., Asnaani A., Litz B.T., Hofmann S. Gender differences in anxiety disorders: Prevalence, course of illness, comorbidity and burden of illness. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45(8):1027–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bommersbach T.J., Stefanovics E.A., Rhee T.G., Tsai J., Rosenheck R.A. Suicide attempts and homelessness: Timing of attempts among recently homeless, past homeless, and never homeless adults. Psychiatr Serv. 2020 doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202000073. (Published online September 29) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nordt C., Warnke I., Seifritz E., Kawohl W. Modelling suicide and unemployment: A longitudinal analysis covering 63 countries, 2000-11. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(3):239–245. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00118-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Table 1 - Crosswalk of ICD-10 codes and DSM-5 mental health disorder categories used in study