Abstract

The crisis provoked by COVID-19 has rapidly and profoundly affected Latin America. The impacts are seen not only in infection and mortality rates, but also in the economic decline and increased inequality that plague the region, problems which have been exacerbated as a result of the pandemic. Women, in particular, constitute one of the groups most heavily impacted by the pandemic, facing higher rates of unemployment and furloughing due to structural discrimination and a subsequent increase in economic dependency as they are forced to return to traditional unremunerated occupations like caregiving and homemaking.

However, it is the increase of direct violences that has received the most media attention and remains the most visible manifestation of the impact of the pandemic on women. Nonetheless, in countries like Mexico and Colombia, said violences are compounded in contexts of criminal violence which make the public sphere more dangerous than the private. Thus, this article focuses the analysis on the structural factors that consign women to a reality in which they permanently face discrimination. This article analyzes the behavior of violence against women in the period of pandemic in the cases of Colombia and Mexico from the perspective of horizontal inequality. It emphasizes that violence against women is a form of discrimination that inhibits the full exercise and enjoyment of one's rights (Interamerican Court of Human Rights [ICHR], 2009). Finally, the responsibility of the State is evaluated in relation to granting women access to emergency assistance and the administration of justice. It is argued that violence against women is a continuum, the most extreme form of which is feminicide, permitted by the failure of the State to guarantee equal protection for women.

Keywords: Violence against women, Inequality, Discrimination, Due diligence, COVID-19

Violence against women; Inequality; Discrimination; Due diligence; COVID-19.

1. Introduction

The spread of COVID-19 throughout Latin America has been rapid and lethal. However, the concentration of victims in the most excluded sectors of society shows that although the virus does not discriminate in its infection, the structural conditions of exclusion that abound in the continent result in that the marginal population (Germani, 1967; Touraine, 1977), constituted of denigrated individuals (Bauman, 2004), are those who suffer the greatest exposure to the virus. Marginalized populations, in large part, tend to dedicate themselves to informal economic activities1, lack access to healthcare, face high levels of income insecurity, and live in conditions of limited habitability, which increases their vulnerability in face of the pandemic.

Even among marginal populations, women, in particular homemakers, are some of the individuals most affected by precarious and unequal living conditions. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), women constitute 10% of the workforce in the social and healthcare sectors, which puts them at the front when facing the epidemic. Furthermore, the additional work that results from activities like childcare, caring for the elderly, incapacitated and infirm, as well as the daily domestic chores like cooking, cleaning, mending and maintaining clothing, and going to collect water, fall disproportionately and unfairly on women (OXFAM, 2020).

In the Colombian case, women have higher rates of exposure to infection as they represent 74% of those employed in the healthcare and social services industries. Some 90% of the people who clean hospitals are women. Additionally, nearly 20% of the Colombian GDP stems from domestic labor and unpaid caregiving, sectors in which laborers face increased risk of infection due to precarious living conditions and the lack of access to social security programs. In the case of Mexico, women have been more affected by the pandemic due to the decrease in paid employment and the increase in unpaid domestic labor. More than 50% of female employment is at risk because of the pandemic, and it is highly probable that the existing employment gaps will grow. Moreover, more than 11 million employed women work in sectors with high risk of infection, which represents 53% of the female workforce in Mexico. Only 30.9% of the total labor hours for women correspond to work in the formal labor market, 66.6% correspond to unpaid domestic labor, and 2.5% of labor hours correspond to the production of goods for exclusive use in the home (Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática [INEGI], 2020c).

Nonetheless, infection rates do not only put the lives of the most excluded populations at risk. The precarious economic conditions aggravated by the preventative measures of total or partial economic shutdown and confinement exposed almost 1,600 million workers in informal sectors, especially women, to even greater levels of poverty (International Labor Organization [ILO], 2020a). The International Labor Organization (ILO) estimates an increase in poverty rates relative to informal workers and their families of about “56 percentage points in the countries with medium-low incomes and in countries with the lowest incomes” (ILO, 2020a).

Using the perspective of horizontal inequality (Stewart, 2002), which focuses on vulnerability due to population group defined by gender, sexuality, race, ethnicity, religion, sect, or place of origin, an analysis of the economic inequality that has been exacerbated by the pandemic shows that women are among the most impacted. This increased economic inequality has also resulted in an increase of the multiple forms of violence that women face. “Women are more exposed to informality in countries with low incomes and medium-low incomes, and at the same time, find themselves in more vulnerable situations than their male counterparts” (ILO, 2020a). It also happens that informal businesses “represent 8 out of every 10 businesses in the world” in which the constant is “principally women who work in precarious conditions, without social protections or means of security or healthcare in their workplace” (ILO, 2020a).

Colombia and Mexico are illustrative cases of horizontal inequality with regards to all four factors used to define the concept: 1. Political participation, 2. Economic inequality, 3. Social inequality, and 4. Cultural status. Inequality in relation to these four aspects has increased across the board due to the pandemic, but the inequality for women in particular has grown the most. The literature about horizonal inequality for women has centered on three structural components: 1. Political participation, 2. Access to education, and 3. Fertility rate (Bussmann, 2010; Caprioli, 2005; Melander, 2005 cited in Stewart, 2008). These three factors all impact the economic inequality of women, linking the woman-centered studies of horizontal inequality to the more general conceptual framework. All three factors of concern show grave inequalities between men and women in both Colombia and Mexico.

In terms of political participation–the first topic of interest to scholars researching horizontal inequality—inequality for women is prevalent in both Colombia and Mexico. In fact, in Colombia, the representative for the UN Council on Women Ana Güezmes García states that in the regional elections for the 2020–2023 period, fewer women were elected to public positions which represents “a step backward” in terms of political participation and equality (Registradora Nacional del Estado Civil [RNEC] & ONUMujeres, 2019), as seen in the 9.38% decrease in the number of women elected governor with respect to the previous election cycle. Only two women were elected governors, representing a mere 6.25% of the total number of governorships at the national level. In terms of city mayor, 132 women were elected for the period 2020–2023, which corresponds to 12.01% of the total number of mayors, a decrease of 0.19% with respect to the previous period. The low percentage of women holding popularly elected positions exemplifies the incompliance of the Quota Law that established a minimum participation rate of 30% for women in political office. However, only 12.12% of governor candidates and 15.20% of candidates for mayor were women (RNEC & ONUMujeres, 2019). In contrast with regional election results, the participation rate of women in the national legislature has increased slightly, but still remains well below the rates established by the Quota Law; 21.3% of the Colombian senate is made up of women and 18.7% of the House of Representatives are women. The presence of women in the judiciary, however, is shockingly low. Only 13.0% of the judiciary is comprised of women, a rate corresponding to less than half of the percentage for Latin America as a whole: 29.2% (DANE, Consejería Presidencial para la Equidad de la Mujer, & ONUMujeres, 2020).

In contrast with Colombia, female participation in the public sphere in Mexico has significantly increased since the 1950s, despite the constant violence against women. The political rights of women have gradually evolved due to legal reforms driven by the feminist movement and social struggle. Among these reforms, the changes in judgement by electoral tribunals, jurisprudence, and the creation of gender quotas stand out.

Constitutional reform and the reformation of electoral law have been essential in establishing equality in representation. The first of these reforms was passed in 1993, when women were first allowed to be included as candidates. In 1996, the same law was again reformed so that no more than 70% of candidates could be of the same gender. In 2002, the Código Federal de Instituciones y Procesos Electorales (Federal Code of Electoral Processes and Institutions) instituted a gender quota of 70/30 in the Congress of the Union and in 2008 the quota was changed to a 60/40 proportion. The reforms were first emitted as a suggestion on part of the political parties, and afterwards as an obligatory measure with a determined gender percentage. Unfortunately, however, the majority of women candidates were chosen to fulfil gender quotas yet were not active in the political system as they were placed in the role of suplente2 (deputy).

The political-electoral reform of February 10th, 2014 marks a watershed in the history of the Mexican legal framework because it requires that political parties offer male and female candidates in equal proportion based on the principals of the relative majority and proportional representation in the Chamber of Deputies, the Senate of the Republic, and local legislative bodies. Moreover, the law requires that both the proprietario (officeholder) and the suplente (deputy) need to be of the same gender (Nieto, 2015). The 2014 electoral reform addressed gender reform in both form and substance because it requires a 50/50 ratio of men to women in political representation. In the 2015 elections, female participation in the Chamber of Deputies only reached 42.8%, but in 2018, female participation in the Chamber reached 48.2%. In the Senate, female representation reached 49.2% in 2018. In the Executive Branch, nine of the 20 secretaries of State were headed by women. Nonetheless, in the 32 federal entities that make up the Republic of Mexico, there are only two female governors: the governors of Mexico City and Sonora. The under-representation of women among the nation's governors has important impacts on political decision-making at the state level.

The second consideration of major concern to scholars of horizontal inequality is education level and its impact on women in the active workforce. The differentiated access to education and to the workforce is seen for women across Latin America, but the inequalities are particularly striking in Colombia and Mexico. For example, statistics found by the Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL – Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean) show that education levels have increased for women across Latin America, yet participation rates in the formal workforce remain low. In most countries in the region, the economic participation rate ranges between 80% and 90% for women with high levels of education, but hovers around 45% for women with lower education levels (CEPAL, 2019).

Limited female participation in the formal workforce and economic inequality are particularly notable in Mexico and Colombia. Findings from the Gran Encuesta Integrada de Hogares (GEIH) 3 conducted by the Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística (DANE4) in 2019 give testimony to the inequalities that existed in Colombia even prior to the pandemic. For example, in Colombia, three out of every 10 women lack an independent income in contrast with one of every 10 men, which is to say that the probability of a woman not having an income on which to support herself is 27.5%, almost three times as much as that of men, 10.2% (DANE [Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística], 2020). The difference in the Workforce Participation Rate of men and women is 20.8 percentage points, and women receive 12.1% less than men in terms of renumeration for their work. The unemployment rate of women is higher than that of men by 9.1% (22.9% of women compared 13.8% of men) particularly for young women between 18 and 24 years old (DANE, 2020).

Furthermore, maternity affects workforce participation rate, 74% of women who are not mothers work in paid employment, but only 65.2% of women with two or three children. It is also reflected in the number of hours dedicated to paid labor, one fifth of employed5 women (19.0%) work less than 20 paid hours per week, and another fifth (23.0%) between 20 and 40 h, which correspond 7.9% and 14.4% of men, respectively (DANE, 2020).

Seventy percent of women who are employed work in the hotel, tourism and service industries, sectors which have been gravely affected by the healthcare crisis (DANE, 2020). In the gastronomic sector, 60% of the labor force is made up of women; however, in May 2020, 10,000 business in the gastronomic industry decided to close, eliminating some 54,000 jobs (DANE, 2020).

In the Mexican case, the employment rate is lower than levels before the pandemic. With respect to the employed population, the drop in employment was greatest in the tertiary sector, principally in the restaurant and hospitality industries. The loss of commerce, full-time jobs, occupation in microbusinesses, and the increase in conditions of informality, inoccupation rate, and underemployment mean that employment in general is in a critical situation (INEGI [Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática], 2020c). According to the International Labor Organization (2020), Mexico has the second lowest female participation rate in the active workforce in Latin America and the Caribbean. Female participation in the paid labor force is only 45.4%, in contrast with 77% for men. The difference has been exacerbated by the pandemic (ILO, 2020b).

Women faced poor working conditions prior to the pandemic because the Mexican labor market shows gaps in terms of access to employment and the number of jobs available. Between the end of 2019 and May 2020, the number of women participating in the Economically Active Population (EAP) increased from 27.4 million to 32.8 million. However, their participation in the paid labor force remains low because they are occupied with unpaid domestic labor. Even when women do have the opportunity to work in paid labor, they work on average 7.4 paid hours less than men in order to balance domestic and caregiving duties with their work (ILO, 2020b).

Furthermore, virtual work and working from home has had strong repercussions on the activity of women in terms of the decrease in paid activity and the increase in caregiving activities with the close of schools and daycares, which has resulted in more women leaving the workforce for childcare. The inequality in the distribution and use of time is an important determinant in workforce inequality and the fact that women bear the brunt of unpaid domestic labors and caregiving has limited their economic participation and constitutes one of the principal barriers to their economic independence. From the total work hours, women dedicate 66.6% of time to unpaid domestic labor, while men only 27.9% (ILO, 2020b).

Simultaneously with decreased political representation and the economic or patrimonial violence derived from economic dependency and precarious labor conditions, violence against women –manifested in physical, sexual and psychological harm or death in the private and public spheres as defined in the Declaration for the Elimination of Violence against Women (Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights [OHCHR], 1993) and the Belém do Pará Convention (Organización de los Estados Americanos [OEA], 1994)– is a common occurrence in the life of women in countries like Colombia and Mexico.

Violence against women should not only be defined based on its manifestations but rather should be understood as the result of the structures of patriarchal domination and discrimination that place women in a subordinate position (Incháustegui and López, 2012) and “seriously inhibit women's ability to enjoy rights and freedoms on a basis of equality with men” (OHCHR, 1992). Thus, violence against women is not only carried out by the individualizable active subject (typically the partner or ex-partner), but rather is also the responsibility of society and the State when they fail to take action to break the continuum of violences against women and stop preventable deaths (Valencia and Nateras, 2020).

Prior to the pandemic, both Colombia and Mexico were characterized by a permanent risk of violence against women. For example, in Mexico 66% of women 15-years-old and older state that they have faced at least one act of violence throughout their lives. Surprisingly, the majority of this violence happens in the community or public spheres (INEGI, 2016). In Colombia as well, women express fear of public spaces. In the Pulso País (National Pulse) survey, 43.9% of women state that they never go out alone at night, 24.9% state that the feel the practice is unsafe and 8.3% consider that it is very unsafe.

The preponderance of violence against women in public spaces shows that in countries like Colombia and Mexico with contexts of criminal violence, violence against women is not limited to its intimate manifestations (like interfamilial violence or violence towards one's partner), but rather is more often seen in non-intimate forms linked to criminal and drug-related violence. This fact is corroborated by statistics regarding the perpetrators of violence against women, used as a proxy indicator in the classification of intimate vs. non-intimate violence. In Mexico, 43.9% of violence perpetrated against women over 15-years old was carried out by their respective partners, whereas 53.1% was carried out by other aggressors (INEGI, 2016).

The importance of the context of criminal violence on the manifestations of violence against women stands out in the case of femicide in particular. In Mexico, for example, 49% of women killed by extreme violence were between 21- and 40-years old. Of these, 44% were working women or students, 51% were beaten, burned, strangled, or stabbed, and 46% died of gunshot wounds. Of the killings classified as femicide, 25% are linked to organized crime, to executions and faceoffs between criminal bands, whereas only 9% take place in the private sphere (OCNF, 2011). Although Colombia does not offer a clear characterization of the perpetrator of lethal violence against women at a national level, the phenomenon coincides with the Mexican case, in terms of the underreporting of non-intimate femicide, the average age of the victims (between 14- and 32-years old) and their low education levels (Sistema de Información Estadístico, Delincuencial Contravencional y Operativo de la Policía Nacional [SIEDCO].6 2020).

At first, it was predicted that the pandemic would increase levels of direct violence against women due to the conditions of total or partial confinement, a supposition that appeared to be substantiated by the increase in the number of emergency calls. However, although the number of emergency calls increased, the levels of violence against women actually decreased even when accounting for the underreporting that confinement implicates. The most dramatic indicator is that of the homicide of women which dropped dramatically, in large part due to the decreased exposure of women to public space. From this statistic, it can be concluded that contrary to the common imaginary dispersed by communication media, in cases like Colombia and Mexico, the presence of criminal violence has made it so that public and community spaces represent even greater risks of violence for women, and that the household is a protected space, strengthened in the periods of confinement with the social accompaniment that this represents.

In light of the apparent contradiction in the patterns of violence in the cases of Colombia and Mexico, the objective of this article is to analyze the determinants of violence against women in the period of pandemic in countries with contexts of criminal violence based on the understanding that violence against women is a form of discrimination, which implies understanding violence not only its physical, sexual and psychological manifestations in the private sphere, but also the forms of inequality that women face as a group (horizontal inequality) that perpetuate said violence. This article is therefore structured as follows: After the description of the materials and method, there is a two-part theoretical discussion. The first theoretical subsection presents the understanding of violence against women as a form of discrimination, and the second discusses how this discrimination, expressed in terms of horizontal inequality, is exacerbated during COVID-19 pandemic. Then, the statistical research is presented, with the discussion of the results divided in these same two perspectives: the exacerbation of horizontal inequality of women in Mexico and Colombia during the pandemic and an analysis of the relation with institutional and direct violences. Finally, the paper offers a conclusion which recompiles the principal findings in relation to the impact of COVID-19 on the increase of violence as a form of discrimination.

2. Materials and methods

This article represents the continuation of the analysis carried out in the research project: A Comparative Analysis of the Social Costs of Urban Violence and Armed Activity Related to Drug Trafficking and Common Crime in Colombia and Mexico in Terms of Migration, Social Cohesion, and Perception of Safety7. This project was co-financed by the University of Medellin and the Autonomous University of the State of Mexico, and case studies were carried out in Medellin, Colombia and the surrounding metropolitan area and in three municipalities in Valle del Río Lerma of Toluca, Mexico: Zinacantepec, Metepec, and Lerma. Publications about the politics of security, cycles of violence, militarization and femicide have all been previously released, but this article is the first to evaluate such topics in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The results presented in this article correspond to Bryman's (1988) triangulation method. A combination of quantitative and qualitative techniques is employed to understand the relation between micro cases –supported by an exercise in inferential statistics and interviews with key informants– and macro processes linked to the social practices that explain violence against women as a form of discrimination. The perspective adopted in this article is based on feminist criminology in which the patriarchal relationship is analyzed. The analytical category of victimization invites recognizing the weight of the structures of subordination in the process of marginalization of women and thusly motivates an analysis not only criminological, but also social and political, which permits the design of public policy to break the cycles of inequality and respond to victims. The fundamental premise of this approximation of the analysis of the phenomena of victimization is that women are agents and political subjects, but that, due to “the lack of protection of women in the criminal justice system before masculine violence” (Fuller, 2008), their agency has been limited by the forms of discrimination imposed upon them.

Mexico and Colombia have been chosen as case studies because, despite their political and structural differences and the persistence of internal armed conflict in Colombia, they share a common characteristic: a context of direct violence that originates in the phenomenon of drug trafficking (Gonzalez and Valencia, 2019). The drug-related violence currently plaguing Mexico can be said to parallel that experienced in Colombia a few decades ago (Palacios and Serrano, 2010; Valencia, 2018; Gonzalez and Valencia, 2019).

The time period of the study is set from March to July 2020, corresponding to the preventative isolation measures adopted in both countries. However, in order to see the statistical variation in violence against women and its impact, the homologous period of March to July 2019 was used as a baseline reference.

In the Colombian case, the confinement in reaction to the COVID-19 pandemic started on March 24th, 2020 with the adoption of Aislamiento Preventivo Obligatorio (Obligatory Preventative Isolation). However, in cities like Medellin and Bogota, this confinement can be traced back a few days more. The weekend prior to the national implementation of the preventative isolation measure, both cities declared a practice isolation that fed into the presidential measure. The measure began to loosen in May 2020 when the construction and manufacturing sectors were grated authorization to re-initiate activity. In July, a larger economic re-opening allowed the reactivation of commerce (except for restaurants, bars, and the hotel and entertainment sectors). From the beginning of the confinement, 43 exceptions to the measure relating to “essential businesses” were declared.

In Mexico, as in Colombia, the preventative measures to be taken for the mitigation and control of COVID-19 were announced in a presidential decree on March 24th, 2020. However, the seriousness of the pandemic was underestimated because President Andrés Manuel López Obrador continued performing work tours8 and offering contracts, a situation which was taken advantage of by local authorities. Before the Federal Government decreed a full quarantine, voluntary confinement and self-isolation was called for. Some federative entities suspended activities before the date published by the Federal Government.

In the decree published on March 24th, all non-essential activities in the public, private, and social sectors were suspended. Furthermore, the State mandated the Jornada Nacional de Sana Distancia (National Healthy Distancing Campaign): even those sectors considered essential could not have meetings of more than 50 people and all business must apply basic measures for hygiene, prevention, and social distancing. Voluntary confinement was recommended for all, but mandatory for people over 60-years-old, pregnant women, and those suffering from chronic illness or autoimmune diseases.

On May 14th, 2020, the Federal Government published the strategy for the reopening of economic and social activities based on the implementation of a graduated epidemiological risk warning system. Based on analyses of levels of infection and use of public space, the epidemiological risk was determined, and the regions with certain risk levels could reactivate specified activities. Regions with high risk of infection were denoted with red, whereas regions with little risk were coded in green. Yellow and orange constitute intermediate risk levels.

In the middle of July, 18 states in the Mexican Republic were in red, and 14 were in orange. By the beginning of August, only 50% were red and the other 50% orange. With an orange-level warning, essential economic activities are returned to full capacity, non-essential economic activities can work with 30% of their personnel, and open-air public spaces are accessible, but at reduced capacity. Currently, only eight states are coded as yellow risk levels, which means that only in these states are all labor activities allowed.

3. Theoretical discussion

3.1. Violence against women as a form of discrimination

Both the Declaration for the Elimination of Violence against Women (1993) and the Belém do Pará Convention (1994) define violence against women as all acts based on gender that causes death, physical, psychological, or sexual harm in the private or public sphere, definitions that invite us not only to understand the multiple manifestations of violence, but its expression in various contexts.

Nonetheless, when talking about violence against women, the example of direct violence manifested as physical violence perpetuated by a sentimental partner is often the first image that comes to mind. The association is understandable as much of the attention given to violence against women in general, and femicide in particular, by judicial authorities as well as academics has focused on the intimate environment. The many typologies created for femicide, for example, amply illustrate the bias in focus, generally dividing femicide into two types: intimate and non-intimate, the first being that which draws the majority of academic attention. The problem with such focuses is that they end up defining violence in function of the victim-perpetrator relationship, not recognizing gender as an underlying conditioner for the violence.

Despite the lack of acknowledgement given to gender as an underlying conditioner for violence against women in the institutional response and academic study, it can be found at the heart of all forms of discrimination that women face. Their condition of gender is a trigger for the violences practiced against women, not only direct violences (physical, psychological, sexual, and economic), but also structural violence (Galtung, 2003), violences derived from the socioeconomic and political system, which amplify the repression and exploitation of women, and, in particular, their horizontal inequality. Sociolinguistic and cultural systems that reproduce the patriarchal model and the socio-institutional structure legitimize the multiple violences experienced by women on a daily basis. In this sense, the violence exercised against women can be defined as the result of the structure of discrimination and the culture of subordination and patriarchal domination to which women are subjected, and which situates them in a position of subordination in the face of the heterosexual predominance and reproduces gender stereotypes (Incháustegui and López, 2012).

Shifting the focus of attention in this article to the structure of discrimination permits understanding violence against women as an act “not only perpetrated by an individualizable active subject, but also by society and the State, when they do not act to break the continuum of violences and stop preventable deaths” (Valencia and Nateras, 2020, p. 66). In 1992, the Committee of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) adopted such a position in General Recommendation No. 19 when it defined “violence against women is a form of discrimination that seriously inhibits women's ability to enjoy rights and freedoms on a basis of equality with men” (OHCHR, 1992). This definition was put into practice by the Interamerican Court of Human Rights in relation to femicide with the sentencing of González y otras (Campo Algodonero) vs México9, where it was stated that “the responsibility of the State and its due diligence are determinants for the perpetuation of discrimination against women” (ICHR, 2009), which “contributes to those homicides that were not perceived in their beginnings as a problem of important magnitude and that now require immediate and direct action on the part of competent authorities” (ICHR, 2009). The court concluded that “it is essential to understand the link between violence against women and the discrimination that perpetuates it to appreciate the reach of the obligation of due diligence” (ICHR, 2009).

Based on this premise, authors such as Monárrez (2011) have argued that femicide has a structural component. For example, in her typology of femicide, the author states that femicide in Mexico is systemic, that these crimes are permitted because the sociopolitical system does not equally protect the rights of women or grant them the same access to justice as men (Monárrez, 2011). Systemic femicide, therefore, refers to the deaths of women that could be avoided due to discrimination, inequality, and the lack of State protection in a patriarchal sociocultural system. The United Nations’ special report regarding Violence Against Women (2012) expanded the definition of systemic femicide to include not only direct femicide, but also indirect: the death of women due to preventable causes that occur because of the lack of protection of their human rights (deaths due to clandestine abortion, practices like female genital mutilation, maternal mortality, human trafficking, organized crime, and gang activity, among others) (United Nations General Assembly, 2012). In the words of Valencia and Nateras (2020), femicide “is not an isolated incident, but the ultimate act of a continuum of violence (…) that is characterized by the lack of State guarantees and protections for the safety of women.”

Understanding the systemic nature of violence against women surpasses the obsession with the victim-perpetrator relationship and transcends the interest in the individualizable subject, the focus of penal action, which has “limited other environments of action directed towards resolving horizontal inequality, preventing gender violence, and increasing State assistance for women” (Benavides, 2015). Incorporating a structural dimension into concept of violence against women and expanding the concept of systemic femicide (Monárrez, 2011) shifts the focus of analysis to the institutional scaffolding that has permitted the perpetuation of this cycle of violence by the omission of due diligence. The analysis offered in this article illustrates how institutions build normative orders that “reduce that status of social minorities (often numeric majorities) to that of garbage, rending their lives precarious and disposable” (Giorgi and Rodríguez, 2009). The effects of the institutionalization of patriarchal sociocultural structures will now be analyzed in light of horizonal inequality.

3.2. The exacerbation of inequality due to COVID-19

Horizontal inequality refers to the inequalities “between determined groups in a culture, groups with members that are differentiated from the rest of society due to questions of race, ethnicity, religion, sect, region of origin, etc.” (Stewart, 2010). Tilly (2003) calls it persistent inequality and argues that the inequality between different groups in the same society due to cultural background (González and Valencia, 2019) is perpetuated by exploitation and the hoarding of opportunities. In contrast with vertical discrimination, horizontal discrimination “refers to the discrepancy between culturally defined groups and not between individuals” (Stewart, 2008, 2009, 2010).

The power of this analytical category stems from its transcendence of the economic determinants of vertical inequality and permits the approximation of political, social, and cultural status factors that are added to groups with identity markers that differentiate them from the rest of society (González and Valencia, 2019). Adopting a perspective of horizontal inequality permits the development of solutions to social problems that positively impact “individual wellbeing, economic efficiency and social stability,” which can reduce violent conflicts (Stewart, 2002; Østby 2008; Stewart, 2009, cited in González and Valencia, 2019).

In the case of women, recognition of the horizontal inequality that plagues them as a result of their identity, and their response in light of such discrimination, permits the start of mobilization that moves beyond obstacles like women's limited inclusion in the public office, reduced access to the public sphere and political recognition, the lack of public recognition of their necessities and the suppression of women in patriarchal and State-centered practices (Rehn and Sirleaf, 2002). Moreover, recognizing horizontal inequalities opens the path for the collective formulation of “processable grievances that are sufficiently strong as to surpass the dilemmas of collective action” (Bahgat et al., 2017).

However, when talking about violence, it is important to bear in mind the reduced social capital of a stigmatized group –in this case women as a group determined by their gender identity– and the persistence of inequality from one generation to the next. Reduced social capital, the multigenerational character of inequality and the continuation of violence have strong impacts on the perception of the group as being incapable of leaving its situation of impoverishment (Stewart, 2009). The persistence of the gender gap, which continues to be large despite affirmative measures promoted in countries like Colombia and Mexico, bears evidence of the long-term impacts of such negative perceptions. As will be seen in the following analysis, the gender gap worsened in the period of the pandemic as women and youth are among the first population groups to be dismissed in the predominate economic model. High levels of unemployment, inoccupation, and inactivity have thusly triggered the transition to informality in the period of confinement.

At this point, Bauman's (2004) concept of denigrated individuals comes into play because the crisis occasioned by COVID-19 evicted a stratum of individuals from society in terms of class, rendering them failed consumers, segregated subjects that are treated as if they were disposable, a marginal population (Germani, 1967; Touraine, 1977; Cingolani, 2009). In this post-Cold War “new regime of marginality” proposed by Wacquant (1996), the processes of des-proletarianization and informality are the mechanisms through which exclusion from the socioeconomic and cultural system occurs. Nevertheless, the marginal mass is heterogenous, unstable, plural and fragmented in character with origins of different extraction and social positions (Salvia, 2010; Delfino, 2012), which impedes the formulation of collective, processable grievances –attempted with the perspective of horizontal inequality. Those individuals of the marginal mass, who Bauman (2004) calls denigrated individuals easily fall victim to the virus because “social and economic inequality ensures that the virus discriminates” (Butler, 2020).

The palliative measures of the State in response to the crisis must be now discussed. According to Wacquant (1996), when the capitalist model of development is incapable of absorbing social surpluses “through efficient, though expensive, social policies”, these individuals are converted into leftover sectors and “– it is necessary to recruit, control, create the conditions for their auto-reproduction, and coopt them with the objective of avoiding their emergence as a potentially disruptive force to the social and political order” (Salvia, 2010). The function of recruiting, controlling and coopting in the case of women is augmented by the subtle mechanisms of cultural violence installed by the patriarchal model that legitimize structural and direct violences, expressed in epochs of pandemic as the return of economic dependence and unpaid domestic labor, in particular caregiving, which essentializes women and dispossesses them of their roles as political subjects, justifying psychological and physical aggression as mechanisms of control and reaffirmation of the heteronormative model.

In today's period of pandemic, recruiting, controlling, and coopting are the prioritized mechanisms of response to this marginalized population to the detriment of “efficient, though expensive, social policies” (Salvia, 2010), including healthcare programs, from which many population sectors are excluded. The treatment of the denigrated population closely echoes Bauman's prediction that “the only job that remains to the government is containment and waste management; there is no remedy other than to treat these people as trash and house them in ‘human landfills’” (Sanmartín Cava, 2019).

Judith Butler (2020) offers the following observations regarding the unequal distribution of the virus and the failure of the State response in relation to marginalized populations:

The virus does not discriminate. We could say that it treats us equally, puts us equally at risk of falling ill, […] At the same time, however, the failure of some states or regions to prepare in advance (the US is now perhaps the most notorious member of that club), the bolstering of national policies and the closing of borders (often accompanied by panicked xenophobia), and the arrival of entrepreneurs eager to capitalize on global suffering, all testify to the rapidity with which radical inequality, nationalism, and capitalist exploitation find ways to reproduce and strengthen themselves within the pandemic zones. (Butler, 2020)

Institutions, therefore, support and perpetuate discrimination against marginal populations like women, placing them in situations of precariousness, ignoring due diligence, and turning their backs in periods of pandemic. At the start of the pandemic period, Butler (2020) predicted: “It seems likely that we will come to see in the next year a painful scenario in which some human creatures assert their rights to live at the expense of others, re-inscribing the spurious distinction between grievable and ungrievable lives, that is, those who should be protected against death at all costs and those whose lives are considered not worth safeguarding” (Butler, 2020) and upon whom fall the economic, social and cultural effects derived from the global crisis, effects of which women are one of the principal victims.

4. Results

4.1. The exacerbation of inequality caused by COVID-19 in data: the cases of Mexico and Colombia

Colombia and Mexico, two of the most unequal countries in Latin America, presented even before the pandemic huge inequalities between men and women in terms of labor and income. This gap clearly illustrates horizontal inequality when women are considered as a minority group marked by their gender. Said situation worsened during the period of isolation and confinement decreed in March 2020 in both countries, as women are considered an expendable population group in the “new normal” economic model. The pandemic accelerated the shift to informality, or unpaid work, and the exacerbation of related violences.

According to the 2020 INEGI survey Encuesta Nacional de Ocupación y Empleo (National Occupation and Employment Survey)10 in Mexico in March 2020, prior to the Resguardo measure, women made up about half of the economically active population11 yet the participation rate12 of women in the formal labor market was only 45.4% compared to 76.5% of male participation (INEGI, 2020a). That means six in every 10 women do not have access to formal employment or find themselves unoccupied13. During the first months of the pandemic period, the limited participation of women in the formal labor market dropped by 9%, reaching 36.4%. In contrast, male participation in the formal labor market dropped by only 7.4%, reaching a new low of 69.1%14 (INEGI, 2020a). Moreover, as a result of the public health emergency, the workday was shortened by 44.6% for women with formal work, 46.2% received reduced wages, and approximately 87.7% did not receive assistance in facing the crisis (INEGI, 2020c) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mexico: Telephone Survey of Employment and Occupation, Men and Women in Comparison (April–June 2020). Source: Original graphic by the authors, using data from INEGI (2020b).

In the Colombian case as well, the economic dependence of women is high: three in every 10 women do not have their own income in contrast with one of every 10 men. Of the women who are occupied, 70% dedicate themselves to commerce, for the most part hospitality, tourism, and the service industry (DANE, Consejería Presidencial para la Equidad de la Mujer, & ONUMujeres, 2020). These economic sectors were some of the hardest hit by the pandemic; commerce dropped by 3.3 percentage points in the period from March to June 2020, in comparison with the same period in 2019 (DANE, 2020).

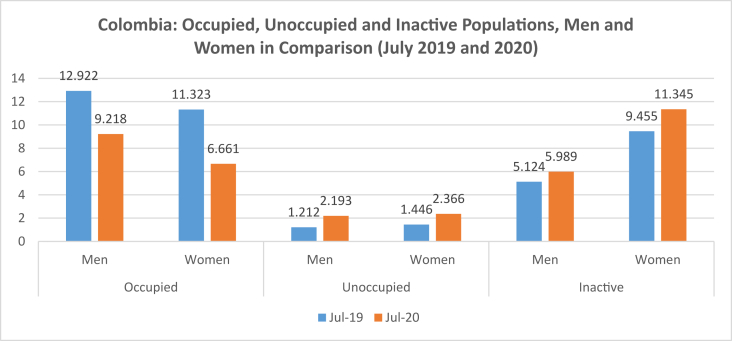

Furthermore, the occupation, inoccupation and inactivity rates are the three indicators used in Colombia to show labor market trends. All three indicators present negative results when comparing July 2020 to July 2019, and when analyzing the statistics based on the gender gap, these differences deepen. For example, when looking at occupation rate during the pandemic, the number of occupied men dropped by roughly 30%, whereas the number of women, by approximately 40%. The inoccupation and inactivity rates show corresponding increases; though the difference between men and women is less, the affection is consistently greater for women than for men (DANE, 2020) (see Figure 2)

Figure 2.

Colombia: Occupied, Unoccupied and Inactive Populations, Men and Women in Comparison (July 2019 and July 2020). Source: Original graphic by the authors, using data from DANE (2020).

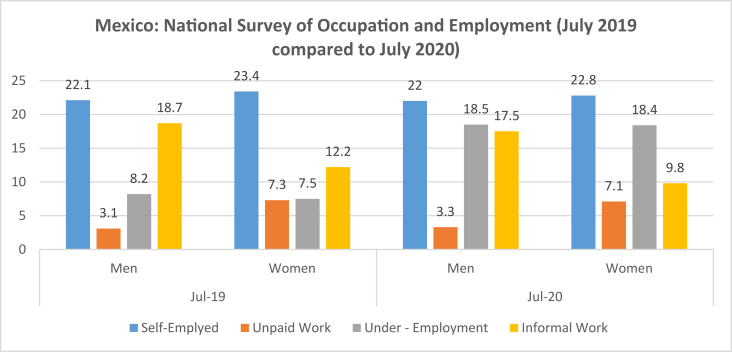

The inequality between the sexes that exists in Mexico and Colombia continues to be seen when underemployment data is analyzed. For example, in Mexico, female underemployment increased by 10.9% between July 2019 and July 2020, passing from 7.5% of the economically active population to 18.4% (INEGI, 2020a). The alarming jump in underemployment is the result of the reduced workday in the public and private sectors derived from the health emergency, in the majority of cases accompanied by a salary reduction, which had a larger impact on the female population (DANE, 2020) (see Figure 3)

Figure 3.

Mexico: Female Unemployment Rate (2019 – 2020 Comparison). Source: Original graphic by the authors, using data from INEGI (2020a).

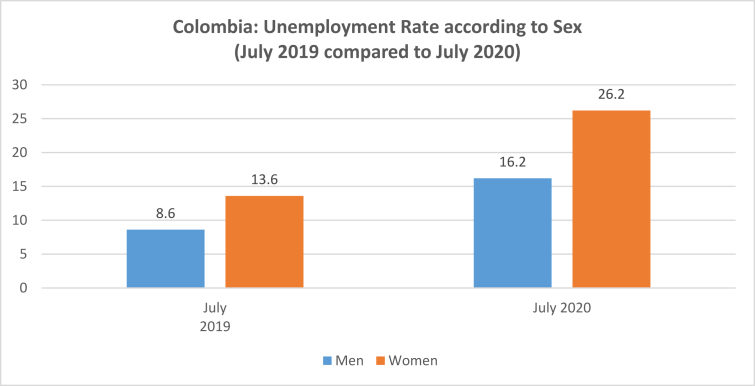

In the Colombian case, the underemployment statistics are even more dramatic. Unemployment rates shows labor deterioration and the persistence of inequality between men and women. In July 2019, the difference in the underemployment of men and women was 5%, with women more likely to be underemployed. The pandemic has exacerbated this difference, and in July 2020, female underemployment was 10% high than male underemployment (DANE, 2020) (see Figure 4)

Figure 4.

Colombia: Unemployment Rate according to Sex (July 2019 and July 2020 Comparison). Source: Original graphic by the authors, using data from DANE (2020).

The large difference in the unemployment rates of men and women illustrates how women are considered to be disposable resources in the current patriarchal capitalist model and are cut out of the formal labor market in times of crises, denigrating them as individuals (Bauman, 2004) and marginalizing them as a population group (Germani, 1967; Touraine, 1977; Cingolani, 2009). In other words, women become excluded from the system based on the processes of des-proletarianization and informality.

For the marginalized population of women, unemployment and inoccupation trigger a whole chain of economic and patrimonial violences beginning with their recruitment into informal labor and their essentialization as unpaid laborers. The real-world situation closely parallels the model of the State's response to marginal populations described in the theoretical section, where the labor market was shown to be a means of control and reclusion (Salvia, 2010).

In Mexico, the pandemic occasioned a mass withdrawal of women from the paid labor market during the second trimester of the year: 8.3% of self-employed women withdrew from the market, 4% passed into unpaid labor, and 2% linked with informal work. The shift to informality implicates a loss of legal protections and constant income insecurity, or even not earning any income for one's work (INEGI, 2020c) (see Figure 5)

Figure 5.

Mexico: National Survey of Occupation and Employment (July 2019 compared to July 2020). Source: Original graphic by the authors, using data from INEGI (2020a).

In short, this section illustrates how the preexisting structural violence fostered a loss of economic independence during the pandemic that hit women harder and aggravated the gender gap. Economic and patrimonial violence against women constitute the first stage in the continuum of violences against women. As demonstrated further ahead, structural violence underlies the most visible forms of violence against women: direct violence which can manifest as intrafamilial violences, sexual violences, and in the worst case, the lethal violence of femicide.

4.2. Violence against women as discrimination from direct violences to structural violences: the cases of Colombia and Mexico

If violence against women is understood as structural or systemic, and not just as direct violence, it becomes clear that violence against women is an expression of discrimination, expressed in the gender inequalities in terms of labor and income, among other factors, as seen above. This change in perspective necessarily facilitates a discussion of State responsibility as, through the omission of due diligence and faulty response and attention to the needs of women, the entity demonstrates clear disinterest in generating spaces free from violence, and finally, in protecting lives. Thusly, the continuum of direct violences manifested against women is explored, demonstrating how the structural problems occasioned by the pandemic, among which is the weakening of the State response, has aggravated these violences.

In the case of Mexico, the Ley General de Acceso de las Mujeres a una Vida Libre de Violencia (General Law for Women's Access to a Life Free from Violence) defines six types of gender violence: psychological, physical, patrimonial, economic, sexual, and digital; simultaneously, it recognizes five environments in which they are presented: familial, labor and scholastic, community, institutional, and femicide (Cámera de Diputados, 2015). In parallel with this typology, the Encuesta Nacional sobre la Dinámica de las Relaciones en los Hogares (National Survey regarding Household Relationship Dynamics)15 catalogues aggressions towards women in the private sphere by their partner as: emotional, economic, physical, and sexual. The survey states that such aggressions are produced in four environments: scholastic, labor, community, and family. Applied in 2003, 2006, 2011 and 2016, the survey shows a steady rise in the number of women15-years old and older who have experienced violence at least once throughout their lives; in 2003, 46.4% of respondents had suffered from violence against women, in 2016, 66.6% (INEGI, 2016) (see Figure 6)

Figure 6.

Mexico: Violence Experienced by Women Ages 15 and Older by Type (2003, 2006, 2011 and 2016). Source: Original graphic by the authors, using data from ENDIREH, INEGI (2016).

Tracing the historical development of violence against women in the private sphere exemplifies how emotional violence is the most frequent type. In 2016, 49% of surveyed women had faced such violence previously. Nonetheless, sexual violence showed the greatest rise, increasing from 7.7% in 2003 to 41.6% in 2016. Physical violence also presented large changes, increasing from 9.3% in 2003 to 34% in 2016. In contrast, economic violence stayed constant; nonetheless, approximately 30.5% of women on average responded that they had experienced economic violence a least once, a rather worrisome statistic.

With respect to the environment in which violence is experienced, it is worth noting that in 2016, the community environment was the preponderant response. Surprisingly, the familial environment is that with the least occurrences of violence against women (INEGI, 2016) (see Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Prevalence of Violence based on the Place where Violence is Most Often Experienced by Women Ages 15 and Older. Source: Original graphic by the authors, using data from ENDIREH, INEGI (2016).

The same phenomenon is observed in the Colombian case, as seen in the results from the Encuesta Pulso País (National Pulse Survey) carried out by the DANE in 2020. In response to the question “How safe do you feel walking in your neighborhood?”, 43.9% of women responded that they never go out alone at night, 24.9% consider it to be unsafe and an additional 8.3% said that they feel this practice is very unsafe.

The insecurity of public spaces for women reveals a primordial characteristic in countries with high levels of criminal violence like Colombia and Mexico: violence against women transcends the private sphere. The intimate vs. non-intimate characterization of violence, thusly, obscures the weight of external violences that women in these countries face. Therefore, in countries like Colombia and Mexico today, femicide cannot only be associated with the intimate sphere; the context of violence becomes determinant as seen in the statistics regarding non-intimate femicide which increase in parallel with upsurges in criminal violence (Valencia and Nateras, 2020).

The context of criminal violence in these countries conditions and relativizes the weight of intimate violences in the total of violence against women. It also changes the perpetrator of the violence, reducing the proportion of sentimental partner perpetrators. In the case of Mexico, the ENDIREH Survey (2016), found that 43.9% of violence against women 15-years and older is carried out by the partner of victim, while 53.1% has other aggressors (INEGI, 2016).

On the other hand, when contrasting the data of violence perpetrated by the victim's sentimental partner (43.9%) with the environment in which said violence takes places – only 10.3% in the familial environment – it can be concluded that even the violence committed partners primarily takes place in environments other than the residence (INEGI, 2016). Recognizing the relative safety of the familial environment is essential to understanding the behavior of violence against women during the pandemic, the analysis for which will be presented in the following section. For example, in contrast with the imaginary presented by communication media which argues that confinement measures have potentialized violence due to the close proximity and extended co-living of the victim and perpetrator in the same residence, for some types of violence, sexual violence for instance, the number of cases has actually decreased. The greater presence of social help networks in the familial environment, the decreased exposure of victims to environments of high risk like the community environment and public space, are two factors among many that can possibly account for the decrease of violence against women during the pandemic. Nonetheless, it must still be acknowledged that public space and going out into community environments is fundamental to daily life, especially for young women, who are their principal victims of femicide.

Thus, with the end of determining if there has been an increase in violence against women or not since the beginning of the Resguardo (Voluntary Confinement) in Mexico or the Aislamiento Preventivo Obligatorio (Obligatory Preventative Isolation) in Colombia in response to Coronavirus, a statistical comparison for the period January to July in 2019 and 2020 was carried out in relation to three crimes: intrafamilial violence, sexual violence, and the homicide of women. In Mexico, however, there is a general statistic that groups all crimes related to gender violence, not including intrafamilial violence. Therefore, before going the comparative for crimes in each country, the consolidated data for gender violence in Mexico will be considered.

Between 2019 and 2020, there was an increase of 35.6% in the total number of gender violence crimes not including intrafamilial violence in Mexico (232 instances in 2019 increased to 315 in 2020). The highest statistic was observed in July 2020, in contrast with the lowest, which was seen in this same month in 2019 (Secretariado Ejecutivo del Sistema Nacional de Seguridad Pública [SESNSP]16, 2020a). Paradoxically, in July 2020, the economic reopening began after a period of stricter isolation. The apparent paradox obligates a closer look at gender violence crimes in 2020, with the end of determining the change in patterns of violence occasioned by the Resguardo.

In the first three months of 2020, the number of reports of gender violence increased considerably in relation to the reports in the same period in 2019 (reaching an average of 100 more emergency calls per month in 2020 compared to 2019). However, for the months of April, May and June (those that coincide with the confinement), the number of emergency calls is lower than the same months in 2019 (with an average difference of 20 reports) (SESNSP, 2020a).

Two hypotheses for the lower number of gender violence reporting are therefore proposed: first, due to the pandemic and the confinement measure, public offices were not operating at full capacity, which means that attention was limited. Second, violence against women is triggered by other actors outside the private sphere and is limited within the residence. The second hypothesis reaffirms the proposal made earlier in the paper with respect to the importance of recognizing a non-intimate category for femicide carried out by an unknown actor in the public sphere as this type of femicide shows the greatest the increase in contexts of criminal violence and has the biggest impacts on the life and dignity of women when conditions discrimination increase their vulnerability (Valencia and Nateras, 2020) (see Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Mexico: Reported Instances of Gender Violence Not Including Intrafamilial Violence (January to July 2019 and 2020). Source: Original graphic by the authors, using data from the SESNSP (2020a).

The following section offers a closer look at three crimes chosen for this analysis: intrafamilial violence, sexual violence and the homicide of women.

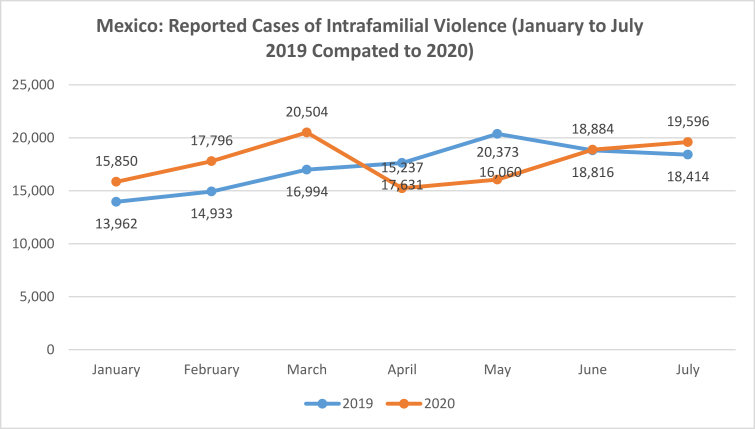

In Mexico, the number of emergency calls regarding intrafamilial violence increased in the period of January to March 2020 with respect to the same period in 2019, just like the calls regarding gender violence in the previous analysis. In April and May, a decrease was observed, reaching points lower than the same period in 2019. Afterwards, in June and July the number of calls once again rise (SESNSP, 2020a) (see Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Mexico: Reported Cases of Intrafamilial Violence (January to July 2019 Compared to 2020). Source: Original graphic by the authors, using data from SESNSP (2020a).

The same behavior can be seen in the Colombian case, where intrafamilial violence increased in the period from January to March 2020 with respect to the same period in 2019. In March, April and May, a decrease to levels lower than the same months in 2019 was observed. Then, in July, along with the loosening of the obligatory preventative isolation measure, there was a new upsurge (Sistema de Información Estadístico, Delincuencial Contravencional y Operativo de la Policía Nacional – SIEDCO, 2020) (see Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Colombia: Reported Cases of Intrafamilial Violence (January to July 2019 Compared to 2020). Source: Original graphic by the authors, using data from SIEDCO (2020).

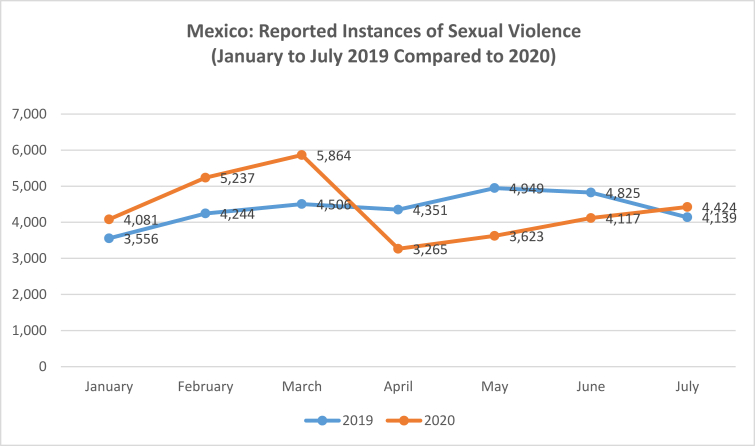

The behavior is similar for the crime of sexual violence. For the case of Mexico, from January to March 2020, there was an increase in emergency calls that surpassed the data from 2019. In March 2020, there were more than 1,300 additional calls compared to March 2019. However, in April, May and June, the statistic dropped, reaching in April a level of 1,000 cases less than in the same month in 2019. The month of July, after the flexibilization of confinement measures, the statistic grows and surpasses the number of cases in the same month in 2019 (SESNSP, 2020a) (see Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Mexico: Reported Instances of Sexual Violence (January to July 2019 Compared to 2020). Source: Original graphic by the authors, using data from SESNSP (2020a).

In the Colombian Case, sexual crimes in the moths of January and February 2020 present similar statistics to the same period in 2019. The difference begins to grow in the month of March, the beginning of the isolation period, and inverts the tendency from 2019, reaching its lowest point in April 2020. But like in 2019, in May there is an apogee, and a new decline in June, corresponding to the behavior of the curve in 2019. In July 2020, the beginning the flexibilization of the isolation, there is an upsurge of more than 500 cases, a surge that doubled rate of increase from July 2019 (SIEDCO, 2020) (see Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Colombia: Reported Instances of Sexual Violence (January to July 2019 Compared to 2020). Source: Original graphic by the authors, using data from SIEDCO (2020).

Starting in 2016, the homicide rate of women in Mexico surged upwards. According to INEGI mortality statistics, the prevalence of the homicide of women was concentrated amongst women age 15-to 44-years old. Yet, in the months January to July 2020, there was a decrease of 30.9% in the total number of homicides, both men and women, with respect to the same period in 2019, as is seen in Figure 13 (26,085 homicides in 2019 compared to 18,010 homicides in 2020). The same decrease was seen though in smaller proportion (3.6%) in the homicide of women. Paradoxically, the number of femicides increased by 4.5% (SESNSP, 2020a), which shows that the confinement stopped homicide, but not femicide.

Figure 13.

Mexico: Instances of Homicide of Men, Homicide of Women, and Femicide (January to July 2019 Compared to 2020). Source: Original graphic by the authors, using data from the SESNSP (2020a).

Femicide is a legal classification for the homicide of women. In the domestic sphere, it is fairly easy to identify the motive of gender in the relationship between the victim and perpetrator. Therefore, the increased confinement during the pandemic drew more attention to the motive of gender in the violence against women in the domestic sphere. Yet, due to the difficulty in isolating gender as a motive in homicide of women in the public sphere, these homicides are rarely considered femicide in the non-intimate setting. Nonetheless, the public sphere remains the site of greater risk for women in terms of gender violence in countries like Colombia and Mexico. During the pandemic, the total number of homicides of women dropped dramatically, which speaks to the fact that the homicide of women and femicide more often occur in the public sphere than in the private, despite the greater attention given to gender in the intimate setting (see Figure 13).

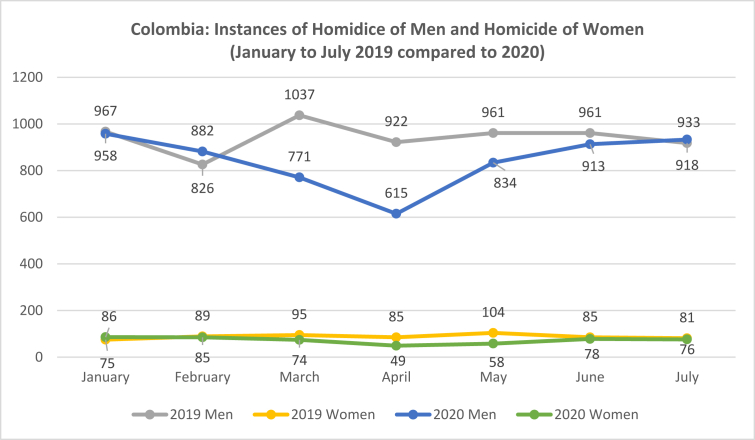

In the Colombian case, the data about the homicide of men and women in the 2019 to 2020 comparison, despite the distance in statistics that exist in the numbers for the two phenomena, do not change substantially. In the case of men, the number of homicides differ in the first months of the year; in 2019 there was a fluctuating behavior with highs in January and March, and lows in February and April. In 2020, there was a drop starting in February that was accentuated in March and April, when the homicide rate dropped by almost 40%, but the homicide rate started to grow again in May when the first steps were taken to expand the exceptions to the obligatory isolation. In July 2020, the data was higher than in the same month in 2019.

In the case of women, although the comparative homicide data for 2019 and 2020 presents a more consistent behavior, when 2020 is analyzed individually, it presents a behavior that is similar to, if more exaggerated than, that of men. The decrease in the number of homicides starts in February, and in April, it reaches a point about 42% lower than the same month in 2019. Like the rate of homicide of men, the rates of homicide of women start to increase in May, but with a slower acceleration. In July, they are once again similar to the 2019 rates (SIEDCO, 2020).

In Colombia, like in Mexico, the prioritization of the study of the homicide of women in the intimate sphere obscures the risks women face in the public sphere. As seen in the indicator of violence that has the least level of underreporting (homicide), the home is a site of protection, not risk as presented in the interpretive frameworks about violence against women propagated by communication media (see Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Colombia: Instances of Homicide of Men, Homicide of Women (January to July 2019 Compared to 2020). Source: Original graphic by the authors, using data from SIEDCO (2020).

The prioritization of the analysis of the homicide of women in the intimate sphere ignores the weight of structural factors that underlie the homicide of women, in particular, femicide. Understanding the structural elements in the sociopolitical system that does not grant women the same protection of their rights nor access to justice as men is key to understanding the systemic nature of femicide (Monárrez, 2011).

In the period of pandemic, the systemic perspective illustrates the institutional disinterest in the adequation of the mechanisms for attention and response to the challenges of confinement and dispossession, shedding light on the perverse game of prioritization of lives implicated in the institutional classification of lives that deserve saving and those disposable, precarious lives that do not (Giorgi and Rodríguez, 2009; Bauman, 2004; Butler, 2020). As seen through this analysis, the lives of women are some of those classified as disposable. The homicide of women in the period of pandemic, like in non-pandemic periods, are preventable deaths that happen because of discrimination, inequality, and the lack of state protection in a patriarchal sociocultural system (Monárrez, 2011; Relatora Especial de la Organización de las Naciones Unidas sobre la Violencia contra la Mujer, 2012).

Looking more closely at violence against women as a continuum in the lives of women shows that femicide is not an isolated one-off event, but rather the fatal outcome of a chain of violences, a process. Considering femicide as a singular event hides the responsibility of the institutions that have perpetuated discrimination, among which is the State that, in its omission of due diligence, has not given an appropriate response to the alerts that women themselves generate in the reporting of the multiplicity of violences they face.

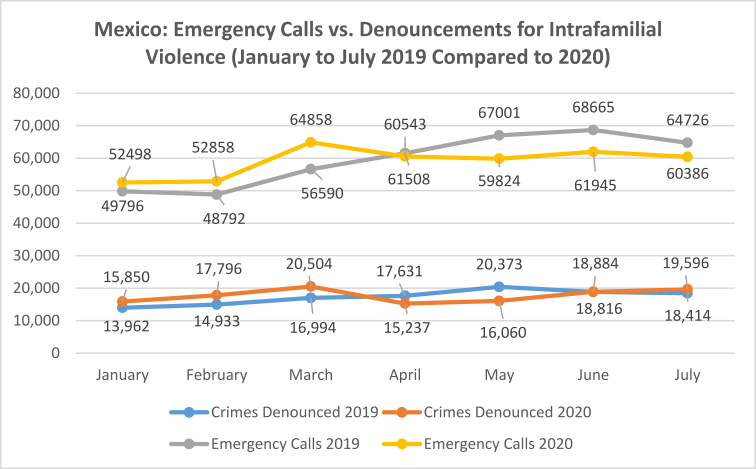

To highlight the inadequacy of the State response, the number of emergency calls is contrasted with formal denouncements in Mexico. The purpose for this comparison is to determine the distance between the number of emergency calls and the institutional recognition of a crime. For the Colombian case, it was not possible to carry out the analysis because of the limited access to data about the emergency lines. However, the statistical analysis done for Mexico is complemented by testimonies from women in the Mesa Departamental para la Erradicación de las Violencias contra la Mujer (Departmental Council for the Eradication of Violences Against Women) in the Department of Antioquia, Colombia. These testimonies give account of the failures in emergency attention and highlight the increase in obstacles women face in accessing healthcare and the justice system during the pandemic.

Before analyzing the data in detail, it is important to note the difficulties in registration and gathering information about sexual violence, the category most academically studied in terms of the violence against women, which include, but are not limited to:1. The low relative importance of sexual violence against women due to the reduced number of cases in comparison to other human rights violations (Roth et al., 2011) and 2. Its irregular distribution with respect to the total population, which Roth et al. (2011) call the “classic elusive phenomenon” that can generate blindness in the sample due to different data collection techniques, including the intentionality in collection (research for punitive action and not analysis). It is utmost importance to remember that that sexual violence is surrounded by high levels of family, social and community stigmatization, which translates to silence on the part of the victims, silence caused by the process of secondary victimization by healthcare institutions or by the justice system. The inadequate attention available to victims is converted into a deterring factor for reporting the crime (Valencia, 2014). Therefore, the generation of the channels for reporting that maintain privacy and reduce victimization, while still being accessible for rural as well as urban populations, is the first step in guaranteeing the attention and ending the conditions of discrimination that permit the perpetuation of cycles of violence.

In both Mexico and Colombia, reports of violence against women are received by general emergency lines for all types of crimes. In Mexico, this number is 91117, and in Colombia, the number is 123. Interestingly, in Colombia, the capital district of Bogotá and departments like Antioquia have created special lines of attention for cases of gender violence. In both cases, these lines were created in response to the need for special attention perceived as a derivative of the pandemic. The Mayor's Office of Bogota created the Purple Line in March 2020 at the beginning of the period of Obligatory Preventative Isolation. In contrast, the Government of Antioquia only initiated operation of their line in July.

Representatives of the Mesa Departamental para la Erradicación de las Violencias contra la Mujer (Departmental Council for the Eradication of Violences Against Women) identify the late implementation of the line as a failure of the principle of due diligence guaranteed by the ICHR: “municipal and departmental governments should be diligent in attending to violence against women and intrafamilial violence”. This obligation is not being fulfilled because of the lack of active emergency lines as mechanisms of protection for women. “Not until August 2020 did the Government of Antioquia implement an emergency call line for women, and it was at the initiative of the governor and not the mayors” (Representative of the Mesa Departamental para la Erradicación de las Violencias contra la Mujer, in the Municipality of Bello, September 8, 2020).

The analysis of sexual violence perpetrated against women begins in Mexico, where the statistics regarding emergency calls are contrasted with the number of official denouncements. With respect to gender violence not including intrafamilial violence, it is important to mention that it is not easy to denounce this type of direct violence to the Prosecutor's Office. Figure 15 shows the comparative data of emergency calls to the 911 emergency line and the official denouncements of these crimes. As can be seen, for every denouncement made, there are on average 68 emergency calls made; in 2020, the gap increased to 71 calls for every denouncement (see Figures 16 and 17).

Figure 15.

Mexico: Emergency Calls vs. Denouncements for Gender Violence Not Including Intrafamilial Violence (January to July 2019 Compared to 2020). Source: Original graphic by the authors, using data from SESNSP (2020a & 2020b).

Figure 16.

Mexico: Emergency Calls vs. Denouncements for Intrafamilial Violence (January to July 2019 Compared to 2020). Source: Original graphic by the authors, using data from the SESNSP (2020a & 2020b).

Graph 17.

Mexico: Emergency Calls vs. Denouncement for Sexual Violence (January to June 2019 Compared to 2020). Note: Crimes Denounced includes crimes of: sexual abuse, sexual harassment, simple rape, equipped rape, incest and other crimes that threaten one's freedom and sexual safety. Emergency Calls includes calls for: sexual abuse, sexual harassment, and incidences of rape. Source: Original graphic by the authors, using data from SESNSP (2020a & 2020b).

Figure 15 shows the disproportionate increase in the number of emergency calls in relation to the increase in denouncements for the analyzed period between 2019 and 2020. Moreover, March, the month in which confinement began, was the month with the highest number of calls and represented an increase of 43.5% with respect to the same month in 2019 (SESNSP, 2020b). This shows how during confinement, telephone denouncement has become a medium through which gender violence is made visible. Moreover, the statistics illustrate the limitations of in-person denouncement, including revictimization and the forms of violence exercised by State institutions.

Simultaneously, the subjectivity of the victim plays a fundamental role in denouncement: first, because the victim is the person who needs to be able to identify if gender violence is being perpetrated against her; secondly, she must know the criminal types that the law defines as gender violence; and thirdly, she needs to know to which institution she can present the denouncement and how to present it. Afterwards, it is necessary to compile proof to be presented before the public ministries so that they can proceed with the denouncement. This step is that which most often inhibits the continuation of the process (see Figure 15).

In the Colombian case, the acknowledgement of one's rights and the recognition of the perpetration of violence against women can be realized through going to an attention point and asking for one of the assistance processes, which “function the same in all municipalities”. However, many women in Colombia do not know what assistance processes are available to them or how to seek redress. A representative of the Women's Council in Granada, Antioquia explains the complexities of the system: “What must be distinguished is the action: one is the reception of denouncements, and the other is responding to the denouncement. There are four organizations that can respond: the National Police, the Family Commissary, the municipal Ombudsman office, and the hospital” (Representative, Municipality of Granada, 3 September 2020).

A major obstacle to accessing redress for violence is the lack of knowledge about where to go or how to ask for help. The representative of the Municipality of Granada in the Council states that “the main obstacle has been ignorance of the route, of the type of violence that they are facing, and the right that women have to ask for recourse” (Representative, Municipality of Granada, 3 September 2020). The representative of Bello echoes the sentiment, concluding “the obstacles are precisely the lack of awareness regarding the means of attention” (Representative, Municipality of Bello, 8 September 2020).

Returning to the statistical analysis of the case of Mexico, the emergency calls for intrafamilial violence in comparison with the denouncements of this crime show a behavior similar that of gender violence. There are a larger number of emergency calls than officially denounced crimes, a relation of 3:1. In other words; for every denouncement, there are three calls made for instances of intrafamilial violence (SESNSP, 2020a & 2020b). This shows the tendency to privilege telephone denouncement over in-person denouncement, due to the processes of revictimization and the forms of violence already mentioned (see Figure 16).

Contrary to the tendencies observed in gender- and intrafamilial violence, in terms of sexual violence, due to the difficulties previously described in its denouncement, emergency calls have a behavior inversely proportional to official denouncement for this type of crime; for every one emergency call, three crimes are denounced on average. However, similar to the previous crimes, the month with the most emergency calls was March (see Figure 17).

There are some important differences in the population distribution in Mexico and Colombia. Mexico is a more urban country than Colombia with better access to digital means of denouncement and attention. Colombia is a highly rural country with significant connectivity difficulties, as much physical as digital. The pandemic has aggravated Colombia's connectivity problems, and the subsequent inadequate attention for victims of sexual and gender violence by healthcare institutions or the justice system therefore disincentivize denouncement. The women of the Mesa Departamental para la Erradicación de las Violencias contra la Mujer in Antioquia identify a series of obstacles caused by the largely rural character of the department that add further challenges to denouncing violence against women in the pandemic period:

Now, in relation to COVID-19, we've had to reinvent the way of reaching out to the community. We've had to return to communication media like TV and radio, but also to tangible means like printed paper, especially in rural zones, where the settlements are so far away, it can take us more than two hours to get there. Can you imagine, then, how difficult it is for rural women to access attention points? We face additional inconveniences as we do not have a means of contacting those women or do not have telephone numbers to call. The resources are so minimal that we don't have the tools to reach out to these communities so that they have access to attention points. (Representative of Municipality of Granada, 3 September 2020).

For this reason, telephone and virtual attention is not a particularly viable option if it is used as the exclusive mechanism to channel the denouncement:

We have a difficult situation with the Prosecutor's Office in relation to the virtual help lines. These lines have actually made denouncements more difficult because they should be done through the entity's webpage and it is not easy, especially because not everyone has access to internet and not everyone knows how to use it. In these cases, we teach the community how to use the help lines. The cases that I know of due to my work in the Oficina de la Mujer, I report to the Prosecutor's Office through e-mail because the community has problems making denouncements on the webpage (Representative, Municipality of Bello, 8 September 2020).