Abstract

Juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML) is a rare pediatric myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasm overlap disease. JMML is associated with mutations in the RAS pathway genes resulting in the myeloid progenitors being sensitive to granulocyte monocyte colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF). Karyotype abnormalities and additional epigenetic alterations can also be found in JMML. Neurofibromatosis and Noonan’s syndrome have a predisposition for JMML. In a few patients, the RAS genes (NRAS, KRAS, and PTPN11) are mutated at the germline and this usually results in a transient myeloproliferative disorder with a good prognosis. JMML with somatic RAS mutation behaves aggressively. JMML presents with cytopenias and leukemic infiltration into organs. The laboratory findings include hyperleukocytosis, monocytosis, increased hemoglobin-F levels, and circulating myeloid precursors. The blast cells in the peripheral blood/bone-marrow aspirate are less than 20% and the absence of the BCR-ABL translocation helps to differentiate from chronic myeloid leukemia. JMML should be differentiated from immunodeficiencies, viral infections, intrauterine infections, hemophagolymphohistiocytosis, other myeloproliferative disorders, and leukemias. Chemotherapy is employed as a bridge to HSCT, except in few with less aggressive disease, in which chemotherapy alone can result in long term remission. Azacitidine has shown promise as a single agent to stabilize the disease. The prognosis of JMML is poor with about 50% of patients surviving after an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT). Allogeneic HSCT is the only known cure for JMML to date. Myeloablative conditioning is most commonly used with graft versus host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis tailored to the aggressiveness of the disease. Relapses are common even after HSCT and a second HSCT can salvage a third of these patients. Novel options in the treatment of JMML e.g., hypomethylating agents, MEK inhibitors, JAK inhibitors, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, etc. are being explored.

Keywords: Juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia, hematopoietic stem cell transplant, azacitidine, mutations, monocytosis, myelodysplastic, myeloproliferative

Introduction

Juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML) is a myelodysplastic (MDS)/myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) overlap syndrome of the pediatric age group characterized by sustained, abnormal, and excessive production of myeloid progenitors and monocytes, aggressive clinical course, and poor outcomes. Unlike acute leukemias, there is no maturation arrest in myeloid differentiation; hence the number of blasts in the peripheral blood (PB) or bone marrow (BM) may be low even in the presence of a high total leukocyte count (TLC). The differentiation pathway is shunted towards the monocytic differentiation and the progenitor colonies of JMML cells show a spectrum of differentiation, including blasts, pro-monocytes, monocytes, and macrophages [1]. The progenitor cells in JMML show high sensitivity to G-CSF in-vitro. The overproduction of the myeloid lineage cells leads to a suppression of other cell lines; consequently, these patients can present with anemia and thrombocytopenia [2]. JMML presents in infants and toddlers and it must be differentiated from other disorders that can have a similar presentation in this age group. JMML is very rare and the diagnosis is often difficult to establish. The criteria for the diagnosis of JMML have been recently updated in 2016 [3]. Recent research has shown that some of the genetic variants of JMML may do well without chemotherapy or with minimal chemotherapy, although the majority of patients need a hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) to achieve cure. Further, the role of azacitidine, a hypomethylating agent has shown promise as a single agent in the pre-HSCT management of JMML [4]. Lately, a lot of agents targeting the molecular pathways are being explored as treatment options for JMML. In view of the recent developments, this study was done to review comprehensively the etiopathogenesis, diagnosis, and management options for JMML.

Epidemiology

JMML accounts for 1% of all pediatric leukemias, with an incidence of about 1.2 cases per million persons/year. The median age at which it is diagnosed is two years and a male predominance is seen (male: female = 2.5). About three-fourths of cases are diagnosed before 3 years of age and by 6 years, 95% of cases are detected. JMML is the commonest subtype in children, accounting for 20-40% of pediatric MDS/MPN [1,2,5-7].

Etiopathogenesis of JMML in the context of the genomic and cytogenetic profile

Inherited diseases predisposing patients to JMML

Neurofibromatosis type-1 (NF-1) and Noonan syndrome (NS) are known to be predisposing clinical conditions for JMML.

NF-1 has an autosomal dominant inheritance and affects 1/2000-1/4500 individuals. Patients of NF-1 have symptoms such as cafe-au-lait macules, neurofibromas, axillary or inguinal freckling, lisch nodules, optic glioma, and osseous lesions [8]. The incidence of JMML with NF-1 is increased by more than 200 times [9]. The cafe-au-lait macules in NF-1 appear by the age of one year, hence establishing the diagnosis of NF-1 in infants with JMML may be difficult. Rarely JMML can be the first presentation of NF-1.

Noonan syndrome (NS) is a genetic disease characterized by facial dysmorphism, growth delay, and heart disease. Children with NS develop JMML-like myeloproliferative disorders (NS/JMML) occasionally, which usually occurs at young ages and has a tendency to regress spontaneously [10]. Recently studies have demonstrated germline mutations in the RAS pathway genes i.e. protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor type 11 (PTPN11) in 50%, son of sevenless (SOS)-1 in 10%, Kirsten rat sarcoma (KRAS) in <5%, and rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma (RAF) in <5% in NS [11-15].

Molecular pathogenesis: RAS signalling pathway

The progenitor cells in JMML show hypersensitivity to granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), because of the dysregulated activation of the RAS signaling pathway [16].

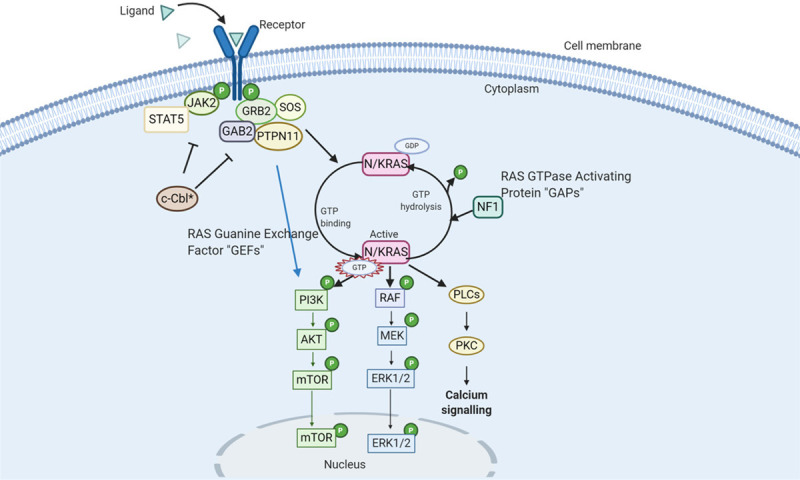

JMML involves cells of multiple lineages, although the predominant findings relate to granulocytic monocytic lineage. The presence of thrombocytopenia and high hemoglobin F (HbF) values in JMML suggests that thrombopoiesis and erythrocytic lineages are also affected. JMML may transform occasionally into acute lymphoblastic leukemia. These points support the hypothesis that JMML is a disease of the progenitor cells [17]. The mutational profile in JMML has been studied extensively, but uncertainty still prevails regarding the genetic aberrations and contributing sequential biological phenomena that result in initiation as well as propagation of disease. The RAS pathway mutations are present in approximately 90% of patients with JMML. Targeted mutational analysis of five RAS pathway components which are protein PTPN11, KRAS, neuroblastoma rat sarcoma [NRAS], Casitas B-lineage lymphoma [CBL], and NF-1 can help in the diagnosis. The mutations can be present in the germline or at the somatic level [7]. Downstream of RAS, the activation of the RAF/mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (RAF/MEK/ERK) cascade, the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway have been implicated in the process of leukemogenesis and sustaining tumor friendly microenvironment (Figure 1). Although the hypersensitivity to GM-CSF has been demonstrated in vitro, no aberrations of GM-CSF receptors have been reported.

Figure 1.

The RAS Signalling Pathway (90% of JMML cases involve mutations in the RAS pathway): N/KRAS proteins (in Pink) alternate between “ACTIVE” and “INACTIVE” states. They are activated in response to signals transferred by surface receptors resulting in the recruitment of guanine exchange factors (GEFs), which stimulates binding of GTP to RAS in place of GDP. The RAS is interrupted by GTPase-activating a protein (GAPS) which hydrolyses GTP to GDP. Mutations of RAS (*) prevent the conversion of RAS-GTP to RAS-GDP - resulting in its constitutive stimulation and hence activation of downstream effectors to induce cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival; PTPN11 gene encodes for Src homology region 2 (SH2)-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase 2 (SHP2). SHP2 binds to RAS and dephosphorylates it, allowing it to bind to RAF and, hence activating the downstream effectors. It can also bind to GRB2 which in turn can bind GEFs and convert RAS-GDP to RAS-GTP. Gain-of-function mutations in PTPN11 (*) increase its phosphatase activity resulting in constitutive activation of the RAS pathway; CBL helps in the regulation of the RAS pathway by inhibiting GRB2 and downregulating JAK2. In the presence of mutations in CBL (*), GRB2 activity becomes unchecked resulting in the activation of the RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK pathway; NF-1 can bind to RAS-GTP and converts it to RAS-GDP. When NF-1 is mutated (*), GAP activity is reduced which leads to increased levels of RAS-GTP and hence activation of downstream pathways.

NRAS or KRAS point mutations can be found in 25% of patients [18]. JMML with somatic RAS mutations is usually aggressive except for a small proportion of somatic NRAS mutated JMML patients who can experience spontaneous remission. RAS proteins are signaling molecules. The RAS protein has an active guanosine triphosphate (GTP)-bound state (RAS-GTP) and an inactive guanosine diphosphate (GDP)-bound state (RAS-GDP) [19]. The levels of these are controlled by guanine nucleotide exchange factors, which transform RAS-GDP into active RAS-GTP; and hydrolysis of RAS-GTP to inactive RAS-GDP by an intrinsic GTPase in RAS. The GTPase activity is enhanced by GTPase-activating proteins (GAP) such as NF-1. RAS-GTP causes downstream cellular responses such as proliferation, differentiation, and survival of cells. Mutations in the RAS lead to defective intrinsic GTPase activity and resistance to GAPs, resulting in the accumulation of active RAS-GTP. A germline mutation in KRAS found in NS causes mild JMML-like myeloproliferative disorder. The mutations in NS are distinct from those reported in patients with cancers and leukemias, and the KRAS T58I allele (found in NS) demonstrates milder effects unlike the wild-type KRAS or the classic oncogenic mutation KRAS G12D [14]. RAS mutations also lead to a lymphoproliferative disorder called RAS associated lymphoproliferative disorder (RALD), with some features mimicking JMML [20].

The commonest RAS pathway mutation in JMML is the somatic PTPN11 mutation [21]. PTPN11 mutations can be found in up to 35% of JMML patients. The PTPN11 gene encodes an Src-homology tyrosine phosphatase 2 (SHP2). The SHP2 has two Src-homology 2 (N-SH2 and C-SH2) domains and a catalytic phosphatase domain [22]. Germline mutations in NS, as well as somatic mutations in JMML, involve residues within the N-SH2 domain or the phosphatase domain [11]. JMML-associated mutations found in the somatic variant of the disease, confer stronger effects on phosphatase activity due to stronger gain-of-function alleles and the disease is aggressive. A less severe form of mutations in NS, where the mutation is germline might explain the spontaneous resolution of the myeloproliferative disease [11].

The neurofibromin gene is located on chromosome 17q11.2 and regulates RAS by the NF protein. The NF-1 gene acts as a tumor suppressor gene. It forms the protein neurofibromin, GTPase-activating protein for RAS protein [23]. In up to 11% of patients of JMML, a clinical diagnosis of NF-1 can be made [24] whereas upto 15% of patients have mutations in the NF-1 gene [25]. The diagnosis of NF-1 can be established clinically and in 50% there is a parent who is affected. The children with NF-1 and JMML tend to be older with more aggressive disease [26]. They have one deficient allele of the NF-1 gene in the germline. In patients, JMML cells show homozygous NF-1 inactivation due to somatic loss of the normal allele in leukemic cells, resulting in hyperactivation of RAS [27]. Most mutations are autosomal dominant missense or nonsense mutations but small insertions or deletions as well as large-scale deletions or chromosomal translocations affecting NF-1 are known [28].

CBL helps in the regulation of the RAS pathway by downregulating the Janus kinase (JAK)-2 pathway. In the presence of mutations in CBL, there is an unchecked conversion of RAS-GDP to RAS-GTP and activation of the RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK pathway. CBL mutations are found in 10-15% of patients and are missense germline mutations. The acquisition of somatic loss of heterozygosity imparts malignant potential to mutated cells. In CBL-mutated JMML, the only recurrent variant is copy-neutral isodisomy at 11q23.3 where the CBL gene is located. No other mutations are observed with CBL mutations. CBL mutation-positive JMML may have a variable prognosis with some patients going into spontaneous resolution whereas others may have an aggressive disease course. Homozygous CBL mutations that arise as a germline event have a trend to have a JMML variant that spontaneously goes into resolution. These homozygous germline CBL mutations may also result in the CBL syndrome a disease characterized by neurologic, vasculitis, and Noonan syndrome-like features [29].

Newer genetic aberrations found to be associated with JMML

With the use of next-generation sequencing technologies for genomic analysis, it has been found that set binding protein-1 (SETBP1) mutations have been detected both at disease initiation as well as progression and are a potential marker of aggressiveness of the disease. Other mutations like JAK3 are known to be associated with JMML [30]. Activating kinase sequence mutations in anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) and ROS1 genes have also been found. The presence of more than one RAS-activating mutation in the same patient (double RAS mutants) characterizes a very aggressive JMML with an increased risk of progression to acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Acquired NF-1 haploinsufficiency in primary PTPN11 mutated JMML is the most frequent of these changes, whereas secondary NRAS, KRAS, or CBL mutations are observed in all JMML subtypes except primary CBL-mutated JMML [31].

Additional mutations affecting the known oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes that affect signal transduction, transcription factors, epigenetic regulation, and spliceosome complex are also found in JMML. In 15% of JMML patients the polycomb repressive complex2 network (like EZH2 and ASXL1), and other epigenetic modifiers (like DNMT3A) are found to be mutated. The increasing number of genetic abnormalities in a patient of JMML is known to correlate with the poor prognosis [32].

Aberrant DNA methylations of genes have been associated with a poor prognosis. The genes such as BMP4, CALCA, CDKN2B, and RARB are known to be hypermethylated in JMML. A RAS A4 isoform-2 which encodes for a GTP activating protein is also hypermethylated in JMML and correlates with poor outcomes. Based on the methylation pattern JMML could be divided into further subtypes. The high methylation group is associated with somatic PTPN11 mutations and poor clinical outcomes. The low methylation ones show underlying somatic NRAS and CBL mutations and have a favorable prognosis. The intermediate methylation group is characterized by somatic KRAS mutations and monosomy 7 [32] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical course of JMML and its correlation with the presence of mutations

| Mutation | Type | Clinical course | Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| NF-1 (10%) | Germline | Features of NF-1, 50% have an affected parent. They have a higher platelet count, a higher percentage of blasts in BM, often diagnosed after the age of 5 years and the JMML is rapidly fatal. | Urgent HSCT |

| PTPN11 (35-40%) | Germline Mutation (Noonans phenotype) | Transient myeloproliferation OR mild disease | Wait and watch OR Mild chemotherapy |

| Somatic (missense mutations) | Lower age of presentation, massive hepatosplenomegaly, high TLC, rapidly fatal | Urgent HSCT | |

| NRAS (15%) | Germline Mutation (Noonans phenotype) | Transient myeloproliferation OR mild disease | Wait and watch OR Mild chemotherapy |

| Somatic heterozygous mutations | Greatest clinical diversity among all mutation’s subtypes Most of these patients are well and show a normal or only slightly elevated HbF. Known to relapse after HSCT | A subset with a low methylation profile can be followed up for spontaneous regression, urgent HSCT in the aggressive ones | |

| KRAS (10%) | Germline Mutation (Noonans phenotype) | Transient myeloproliferation OR mild disease | Wait and watch OR Mild chemotherapy |

| Somatic mutation | Lower age of presentation 50% have monosomy 7, aggressive disease | Urgent HSCT | |

| CBL (15%) | Germline (Isodisomy of 11q is associated) | Sometimes the JMML occurs as a part of the CBL syndrome In the majority the disease is self-limiting. If progression occurs may need intervention. | Wait and watch may be adopted if the clinical condition permits especially in the case of CBL syndrome HSCT if disease progression occurs |

JMML: Juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia; NF-1: Neurofibromin-1; CBL: Casitas B-lineage lymphoma; PTPN11: Protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor type; KRAS: Kirsten rat sarcoma; NRAS: Neuroblastoma rat sarcoma; BM: Bone marrow; TLC: Total leukocyte count; HSCT: Hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

Cytogenetic alterations in JMML

Monosomy of chromosome 7 is present in about 25% of JMML patients and is the most common karyotype aberration in JMML. Other abnormalities may be found in a further 10% of patients. Karyotype abnormalities are also known to be acquired during treatment and/or in event of progression into blast crisis. Monitoring for these is an important aspect of treatment response assessment in JMML [33]. The other cytogenetic abnormalities found in JMML are the deletion of chromosome 5q and the deletion of chromosome 7q. JMML children with monosomy 7 have lower leucocyte count, near-normal HbF levels, macrocytosis, and erythroid predominance in BM. Approximately 50% of KRAS mutated JMML have monosomy of chromosome 7 [17].

The hyperactivation of the RAS pathway plays an important role in the pathogenesis of JMML [34,35]. It is unclear whether only the mutations of the RAS pathway genes are sufficient to cause JMML or epigenetic modifiers and other associated mutations are critical too. The role of other genetic abnormalities like monosomy of chromosome 7, which is common in JMML, needs more elaborate research.

Clinical presentation

Patients of JMML may present with fever, cough, pallor, infections, splenomegaly hepatomegaly, lymphadenopathy, and rash. Splenomegaly is found in all cases and is a prerequisite for the diagnosis of JMML. Skin rash and lymphadenopathy are caused by leukemic infiltration and are seen in about 50% and 80% of cases, respectively [36].

The skin involvement includes eczema, xanthoma, café-au-lait spots, and juvenile xanthogranuloma. The café-au-lait spots may also be present in children with germline mutations in the NF-1 and CBL gene [29] and melanocytic lesions can be observed in patients with germline mutations in genes involved in the RAS signaling pathway [37].

Gastrointestinal involvement can manifest as intractable diarrhea, hemorrhagic manifestations, and infections. These patients may present with cough and respiratory distress and chest x-ray findings include peribronchial and interstitial pulmonary infiltrates. Although central nervous system (CNS) involvement in JMML is rare, a few patients have been reported with CNS leukemic infiltration, ocular granulocytic sarcoma, diabetes insipidus, and facial palsy [5].

Differential diagnosis

Non-malignant disorders mimicking JMML

It is imperative to rule out non-malignant disorders mimicking JMML in a clinically suspect case. Viral infections like Cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), human herpesvirus-6 (HHV-6), and parvovirus B19 may present with features mimicking JMML. Congenital intrauterine infections can also present with cytopenias, lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly and are important non-malignant differentials of JMML. The differentiation of JMML from viral infections may require the demonstration of chromosomal and/or genetic aberrations and the presence of a mutation of the RAS pathway may help to establish the diagnosis of JMML.

Infection with HHV-6 and CMV in JMML patients may show increased spontaneous proliferation of granulocyte and monocyte precursors, hypersensitivity to GM-CSF, and abnormal proliferation of B-lineage cells with the NRAS mutation respectively, making the diagnosis difficult [38,39]. The diagnosis is challenging in such a scenario, where it has to be established by viral polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and genetic mutation analysis. Sometimes, the association of concurrent viral infections with underlying JMML results in poor outcomes. The presence of viral infections must be excluded in all cases of JMML by serological tests and PCR.

Immunodeficiencies, most commonly Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome (WAS) and leukocyte adhesion defect (LAD) may present with similar features and should be ruled out. Infantile malignant osteopetrosis can be a close mimicker of JMML and can be ruled out in most cases by radiographic imaging which shows increased bone density. Familial hemophagolymphohistiocytosis (HLH) may present with similar symptomatology in infancy and should be ruled out with the help of blood/bone marrow tests and genetic tests [40].

Myeloproliferative neoplasia (MPN) in early childhood mimicking JMML

MPN with receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) translocations may mimic JMML and these patients may benefit from RTK-targeted inhibitors. ALK receptor tyrosine kinase rearrangement in atypical JMML has been reported. Myeloid neoplasia with ALK rearrangement and monosomy 7 is found in all age groups [12,41].

MPD with eosinophilia and constitutively activated platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFR-α), PDGFR-ß, or fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1) can present with leucocytosis and organomegaly in very young children, and thus need to be differentiated from JMML [42]. A clinical presentation akin to JMML is noted in some patients with GATA2 deficiency [43].

Infantile acute leukemia with KMT2A (MLL) rearrangement can have a massive enlargement of the liver and spleen and patients with low blast count may be difficult to differentiate from JMML [44].

Differentiating JMML from NS-associated myeloproliferative disease and other RASopathies

NS is a genetically diverse and the most common disorder of the RAS pathway (RASopathy) occurring in 1 of 1000 to 2500 births [45]. Patients with NS are predisposed to several hematological abnormalities like thrombocytopenia, platelet dysfunction, and von-Willebrand disease. Hepatosplenomegaly is a common clinical finding in NS. Around 5% of infants with NS develop an MPD, which in its severe form clinically resembles JMML. The majority of these children with NS/MPD harbor germline PTPN11 mutations. It slowly regresses over months to years in the majority [46,47]. There are rare cases of NS/MPD with secondary monosomy 7 that achieve spontaneous remission with the persistence of monosomy 7 [10]. On the contrary, a few progressions to AML have also been reported [48].

CBL syndrome due to germline missense CBL mutations is a constellation of impaired growth, delayed development, cryptorchidism, and a predisposition to JMML. Some patients of this syndrome experience spontaneous regression of their JMML but develop vasculitis later in life. Monocytosis, leukocytosis, lymphoproliferation, and autoimmunity, can be a feature of RAS-associated autoimmune leukoproliferative disorder (RALD) previously called autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome type IV. This can present with several features that overlap JMML as well as with identical somatic mutations in KRAS or NRAS [49].

Diagnosis

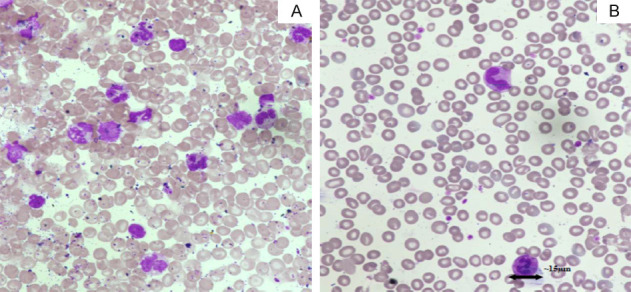

Peripheral blood film evaluation: The PB film (PBF) examination is crucial for establishing the diagnosis of JMML. Anemia with the presence of nucleated red blood cells (NRBCs), leukocytosis, monocytosis, a shift towards immaturity in the granulocytes, and thrombocytopenia are characteristically present in patients with JMML. A myeloid shift to the left is present and blasts including promonocytes constitute less than 5% of all cells. Absolute monocytosis of >1000/mm3 is a diagnostic criterion for JMML but in isolation, it is neither specific nor sensitive because it can be a feature of infections. Thrombocytopenia is a common finding and can be sometimes severe (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Peripheral blood smears (PBS) from a patient with JMML (Jenner-Giemsa × 600). A. Pre-transplant PBS showing increased leucocyte count, monocytosis, myeloid precursors, and reduced platelet counts. B. Post-transplant PBS of the same patient showing normal leucocyte count and platelet counts.

Bone marrow examination: The BM findings may support the diagnosis of JMML but are not specific. There is a myeloid predominance and hypercellularity. The myeloid to- erythroid (M: E) ratio may vary from 0.1 to >94. The number of myeloid progenitors, blasts, including promonocytes are increased but the blast count is less than 20%. Auer rods are not seen. The monocytes comprise 5% to 10% of the marrow cells and nonspecific esterase or immunohistochemistry for CD14 may help to highlight the monocytic component. The erythroid progenitors are megaloblastic. Megakaryocytes are decreased in number [16].

Other frequently affected organs are lymph nodes, skin, and the respiratory tract. Liver and spleen infiltration is found in most cases. Myelomonocytic infiltration of the lungs is accompanied by infections, occasionally causing significant morbidity. The gastrointestinal tract can also be involved, but rarely [16].

Immunophenotyping: There is no specific immunophenotypic characteristic of JMML. The monocytic component in the bone marrow aspiration and extramedullary tissue can be detected by immunohistochemistry (IHC) markers like CD14, CD11b, CD68R, or lysozyme. Rarely myeloperoxidase (MPO) may be positive in the extramedullary involvement of JMML.

Hemoglobin F (HbF) levels: The majority of JMML patients have higher HbF levels except for the ones with monosomy 7 where it may be near normal.

Hypergammaglobulinemia: About 50% of patients have hypergammaglobulinemia. One-fourth of patients may show autoantibodies and positive direct antiglobulin test.

GM-CSF hypersensitivity: Hematopoietic precursor cells of JMML demonstrate hypersensitivity in colony-forming assays to GM-CSF or spontaneous proliferation in vitro without the addition of an exogenous growth factor. Spontaneous proliferation and hypersensitivity to GM-CSF are used as criteria for the diagnosis of JMML to be established. This assay’s limitations are that this technique is not standardized. GM-CSF hypersensitivity assay is not specific to JMML and is time taking [1,38,50].

STAT-5 phosphorylation assay: phosphorylation of CBL by aSrc family kinase and by the JAK2/STAT-5 pathway is the other pathway that is activated downstream to the GM-CSF receptor. JAK2-activated hyperphosphorylation of STAT-5 in response to GM-CSF has been identified as a hallmark of JMML. It is one of the criteria used to establish the diagnosis of JMML. Phosphospecific flowcytometry in CD33+/CD34+ or CD33+ CD14+CD38low cells has been validated to detect hyperphosphorylation of STAT-5 protein in BM (or PB) cells in response to low doses of GM-CSF [51].

Cytogenetics: Monosomy 7 and other cytogenetic abnormalities may be detected on the karyotype analysis [1].

Molecular alterations: Mutations in the NRAS, KRAS, PTPN11, CBL, and NF-1 genes may be detected by genomic sequencing [1].

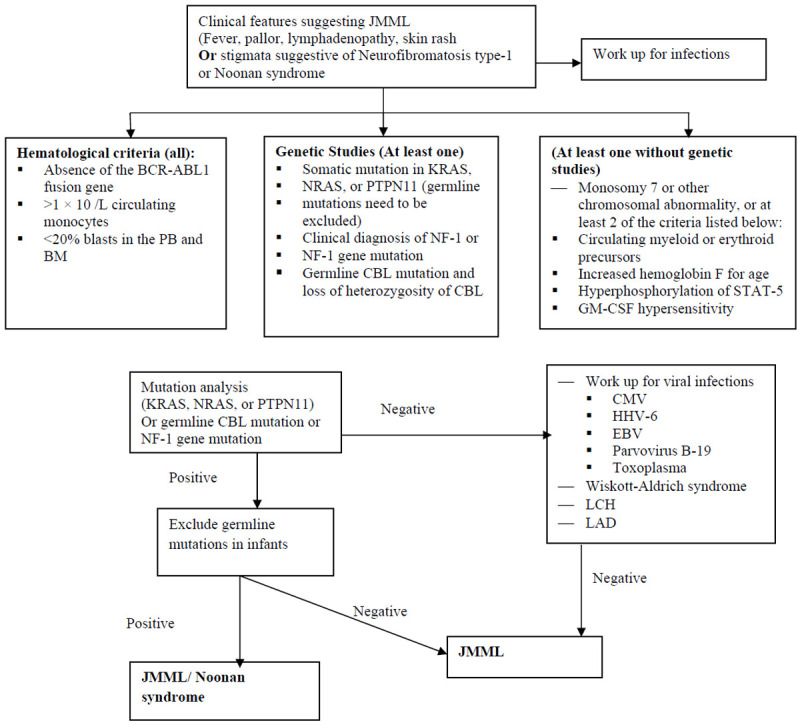

Diagnostic criteria for JMML have been shown in Table 2 [3] and the diagnostic approach has been provided in Figure 3.

Table 2.

Diagnostic Criteria for Juvenile Myelomonocytic Leukemia (JMML) Per the 2016 Revision to World Health Organization Classification [52]

| Diagnostic criteria of JMML | ||

|---|---|---|

| Category 1 (All are required) | Clinical and Hematologic Features | Absence of the BCR-ABL1 fusion gene |

| >1 × 10/L circulating monocytes | ||

| <20% blasts in the peripheral blood and bone marrow | ||

| Splenomegaly | ||

| Category 2 (One is sufficient) | Genetic Studies | Somatic mutation in KRAS, NRAS, or PTPN11 (germline mutations need to be excluded) |

| Clinical diagnosis of NF-1 or NF-1 gene mutation | ||

| Germline CBL mutation and loss of heterozygosity of CBL | ||

| Category 3 (patients without genetic features must have the following in addition to category 1) | Other Features | Monosomy 7 or other chromosomal abnormality, or at least 2 of the criteria listed below: |

| Circulating myeloid or erythroid precursors | ||

| Increased hemoglobin F for age | ||

| Hyperphosphorylation of STAT-5 | ||

| GM-CSF hypersensitivity | ||

NF-1: Neurofibromin-1; CBL: Casitas B-lineage lymphoma; PTPN11: Protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor type; KRAS: Kirsten rat sarcoma; NRAS: Neuroblastoma rat sarcoma.

Figure 3.

Diagnostic approach to juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML) [PB = peripheral blood; BM = bone marrow; CMV = Cytomegalovirus; EBV = Epstein-Barr virus; GM-CSF = Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; HbF = Hemoglobin F; HHV-6 = Human herpesvirus 6; LCH = Langerhans cell histiocytosis; LAD = Leukocyte adhesion defect; STAT-5 = Signal transducer and activator of transcription-5].

Treatment

Supportive care

Hydroxyurea (25-30 mg/m2/day) can be used as a therapy to tide over the period to definitive cure by allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant HSCT [53]. Hydroxyurea can also be given if the TLC is more than 100,000/mm3 to prevent end-organ damage due to high TLC. Hemoglobin should be maintained above 8 gm/dl and platelet counts above 20,000/mm3. Oxygen support, antibiotics, and pain relief should be used when necessary.

Chemotherapy

JMML is fatal if not treated, except in a few cases where spontaneous remission can occur. Allogeneic HSCT is the only cure available to date. The median duration of survival of patients without HSCT is 10-12 months [5]. There is no proven chemotherapy known to achieve complete remission for JMML (Table 3).

Table 3.

Chemotherapy regimens used for JMML

| Type of study | Median age | Sample size | Chemotherapy | Survival | Remarks (Reference) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retrospective | 36 m | 12 | Low dose chemo (6) Standard dose chemo (6) | No survival benefit | Heterogenous treatment [57] |

| Retrospective (Case series) | 48 m | 3 | AML-BFM-97 | Median survival 4 months | [58] |

| Retrospective (Case series) | - | 8 | Hydroxyurea (4) Low dose cytarabine (1) | - | [53] |

| Prospective | 20.5 m | 11 | Low doses of daunorubicin or cytarabine | Overall survival 7 months | The use of intensive combination chemotherapy in children with JMML can result in long-term survival in some patients [59] |

| Retrospective | 33 m | 21 | A-V3 Protocol (Cytarabine Etoposide VCR) | 3-yr EFS (66.2 ± 14)% | [61] The survival was more for patients who received a HSCT after the chemotherapy compared to the ones who got chemotherapy alone |

| 3-year OS (76.2 ± 14.8)% | |||||

| Retrospective | 12 m | 20 | 6-mercaptopurine and cytarabine | Median survival 44 months | 6-mercaptopurine and cytarabine may be used as a bridge therapy [55] |

Low-dose chemotherapy-Low-dose cytarabine, 6-thioguanine, 6-mercaptopurine, hydroxyurea, and others Standard dose chemotherapy-Induction schedules for acute myeloid leukemia, anthracyclines, cyclophosphamide, standard-dose cytarabine, etoposide, and others; A-V3 protocol: Cytarabine: 100 mg/m2, Etoposide, 100 mg/m2, Vincristine: 1.5 mg2/m.

Several chemotherapeutic protocols including intensive protocols like those employed in AML therapy or milder leukemia maintenance-type combination schemes, and single-agent chemotherapy have been used in JMML [53]. The use of 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP) with or without low-dose cytarabine has demonstrated a partial and transient response in few cases. Recently Abdul Wajid et al [54] reported a retrospective study of 33 patients and 20 of them received at least one cycle of sequential chemotherapy (subcutaneous cytarabine and oral 6-MP). Six out of 20 who received chemotherapy showed a response (two patients achieved completion, and four patients achieved partial remission). These results suggested that sequential therapy with 6-MP and cytarabine could be an option in patients in whom HSCT is not feasible or as a bridge therapy in those awaiting HSCT. In a few patients, it can result in the cure of the disease. Intensive chemotherapeutic agents have not proved effective and have a risk of morbidity or therapy-related death [27]. Other chemotherapy agents like fludarabine and high-dose cytarabine combinations have also been used to achieve remission in the presence of aggressive disease or massive pulmonary infiltration [55].

Until now, no standard pre-HSCT chemotherapy protocol has proven to have an impact on post-HSCT relapse incidence.

Azacitidine in JMML

Azacitidine which is a DNA hypomethylating agent has been used in JMML. It is known to stabilize the disease and also induce complete remission in a subset of patients, before HSCT and also the following relapse after HSCT. Although the agent is unlikely to be employed as a curative option, it can decrease the disease burden and can be an effective drug during the window period before HSCT [4].

Furlan et al reported a 1.5-year child with JMML treated with azacitidine (100 mg/m2 over 1 hour intravenously on 5 days, repeated every 4 weeks). Azacitidine was well tolerated. The clinical and hematologic response was impressive and monosomy 7 disappeared. HSCT was performed in the child after achieving good control [56]. In a retrospective study of 12 children by Annamaria Cseh et al, 9 children received azacitidine before HSCT, and 3 received after the relapse of the disease. The study concluded that low-dose azacitidine is effective and tolerable in JMML and complete clinical, cytogenetic, and/or molecular remissions can be achieved before allogeneic HSCT [4]. Fabri et al treated 3 patients with azacitidine at a dose of 75 mg/m2 intravenously on days 1 to 7 of a 28-day cycle before the HSCT and documented a good response. The drug was well tolerated without any adverse effects [57]. Hashmi reported an infant with JMML with somatic KRAS G12A mutation and monosomy 7 who achieved sustained remission after 6 cycles of azacitidine [58].

Based on the evidence provided by these studies, the role of conventional low dose chemotherapy or azacytidine in JMML is limited as a modality to bridge to HSCT or for the intent of palliation. Only a few patients have done well with chemotherapy alone and in most of these, the underlying genetic mutation was not determined. It is, therefore, possible that the ones who go into long term remission with chemotherapy alone are the ones with the good risk molecular alterations. High dose chemotherapy has been associated with increased morbidity and mortality without a benefit in survival. In situations where HSCT is not feasible, low dose chemotherapy may be tried. It should also be employed in case germline mutations of NRAS, KRAS or PTPN 11 mutations are present in the JMML patient and mildly symptomatic patients with CBL mutations (only if a wait and watch policy fails). Further treatment in these cases should be tailored to the response.

Splenectomy for JMML

The lack of treatment options in the past, with HSCT’s availability at only a few centers around the world, clinicians had to resort to splenectomy for symptom control in JMML. It has also been used as an option for palliation if HSCT is not possible and the disease appears to be unresponsive to ongoing chemotherapy. Splenectomy has been known to decrease the requirement of blood transfusion and the requirement of platelets but with the increased risk of infections [59]. Splenectomy has been done in JMML to decrease the disease burden and promote engraftment after HSCT. Over the years this approach has gradually fallen out of favor and its indiscriminate use is not recommended. The spleen size or splenectomy before HSCT is not known to affect the outcomes of JMML post-HSCT.

In the presence of hypersplenism, platelet refractoriness, or massively enlarged spleen the procedure may be contemplated after an analysis of the risks and benefits [55].

Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant (HSCT) in JMML

Response to chemotherapy is generally transient in a majority of cases. In a small subset, the wait and watch strategy can be adopted; else the majority succumb to the disease if untreated in 10-15 months from diagnosis. The commonest cause of death is pulmonary infiltration due to the JMML, disease itself. Allogeneic HSCT is to date the only curative option for JMML and the expected long-term survival even after allogeneic HSCT is 50%. The commonest cause of death after HSCT is the relapse of the disease. Second allogeneic transplantation may be curative in some patients who relapse after HSCT [1].

Matched sibling donors (MSD) or matched family donors (MFD) are first choices as donors. Recent studies have suggested that even matched unrelated donor (MUD) transplants do equally well. Umbilical cord blood transplantation (UBCT) may be an option for those who are in urgent need of HSCT and are lacking a donor. In UCBT the time interval necessary to identify a suitable umbilical cord blood (UCB) unit is short and the stem cells are sufficient as these patients usually have low bodyweight [60,61].

The HSCT in JMML has led to a cure in approximately 50% of patients. Pre-transplant treatment is still a matter of debate. In the initial years, total body irradiation (TBI) based protocol was used in conditioning but TBI was replaced with chemotherapy based conditioning options owing to its toxicity in young children. Busulfan is the most commonly employed agent in association with other chemotherapeutic agents and the use of multiple alkylating agents with non-cell-cycle-specific action may help in cure as JMML is a stem cell disorder characterized by cell dormancy [62].

Myeloablative conditioning using busulfan, cyclophosphamide, and melphalan was used by the EBMT group, using unmanipulated hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) from human leukocyte antigen (HLA) identical and unrelated donors, with BM, PB, and cord blood (CB) being used as sources. The 5-year probability of event-free survival for children given HSCT from either a relative or a MUD was 55% and 49%, respectively. Older age and female sex were associated with poor outcomes and disease recurrence was a major cause of treatment failure [48].

Age older than 2 years, female donor to male recipient, matched unrelated donor or mismatched non-cord donor, total body irradiation (TBI) and no serotherapy in conditioning regimen had poorer outcomes in a series of 91 JMML patients who underwent HSCT between 1986 and 2011 in France. Busulfan, cyclophosphamide, and melphalan conditioning regimen was associated with a decreased risk of relapse. Serotherapy was associated with a decreased risk of non-relapse mortality. In this series at 6 years, overall survival (OS) was 59% and the cumulative incidence of acute graft versus host disease (GVHD) was 48% [63].

In 129 children who underwent HSCT for JMML Yoshida et al in 2020 observed a 64% overall survival. They found that a conditioning regimen of busulfan/fludarabine/melphalan used in 59 patients was superior with a 5-year OS rate of 73% and the cumulative incidences of relapse and transplantation-related mortality (TRM) were 26% and 9%, respectively. Chronic GVHD was associated with a lower risk of relapse [64] (Table 4).

Table 4.

Studies depicting outcomes of HSCT in JMML

| (n) Median age | Years of study | Source of Stem cells | Conditioning | GVHD prophylaxis | GVHD | OS% (follow up) [Reference] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (11) 18.6 m | 1998-2013 | BM = 4 | -Bu Cy Mel (8/11) | CSA + steroids (4) | Ac GVHD = 6/11 | 72.7 % (4.2 yr) [71] |

| UCB = 7 | -ATG in 5 | CSA+MMF(1) | Chr GVHD = 3/11 | |||

| (MRD = 3 | CSA+MTX(1) | |||||

| MUD = 1 | TAC+MTX(4) | |||||

| UCB = 7) | ||||||

| (11) 9 m | 1999-2004 | BM = 6 | -Bu Cy Etop (6/11) | CSA+MTX | Ac GVHD = 8/11 | 54.5% (15.5 m) [72] |

| UCB = 4 | -TBI in 3 | Chr GVHD = 4/11 | ||||

| PB = 1 | ||||||

| (15) 13.3 m | 2013-2015 | PB = 1 | -Bu Cy Mel | TAC+MMF | Gr I Ac GVHD = 20% | 47% (29 m) [73] |

| BM = 13 | -Bu Flu | Gr II-IV Ac GVHD = 27% | ||||

| UCB = 1 | -ATG in MUD and UCB HSCT | Chr GVHD = 7% | ||||

| (MRD-5 MUD = 7 | ||||||

| MMUD = 2 | ||||||

| UCB = 1) | ||||||

| (100) 30 m | 1993-2002 | PB = 14 | -Bu Cy Mel | CSA alone in MRD (32/48) | Gr II-IV Ac GVHD = 40/100 | 64% (5 yr) [47] |

| BM = 79 | CSA+MTX+ | Chr GVHD = 13/86 | ||||

| UCB = 7 | ATG+Mo ab for MUD (41/52) | |||||

| (MRD = 48 | ||||||

| MUD = 45 | ||||||

| UCB = 7) | ||||||

| (7) 30 m | 2007-2014 | BM = 3 | -Bu Mel | TAC+MTX | - | 100% (25.3 m) [74] |

| UCB = 3 | -Alemtuzumab in MUD | MTX not used in UCB | ||||

| Not mentioned = 1 | -ATG for UCB | |||||

| (MRD = 2 | ||||||

| MMRD = 1 | ||||||

| MUD = 1 | ||||||

| UCB = 3) | ||||||

| (27) 24 m | 1990-1997 | PB-3 | -Cy Bu Etop (Mel, Thiotepa, and Ara-C were other agents used in different patients) | MTX, CSA, and TAC (different combinations in different patients) | Gr II-IV Ac GVHD = 15/26 | 57.9+-11.0 (4 y) [75] |

| BM = 23 | -TBI in 18 | Chr GVHD = 10/21 | ||||

| UCB = 1 | ||||||

| (MRD = 12 | ||||||

| MMRD = 4 | ||||||

| UCB = 1 | ||||||

| MUD = 10) | ||||||

| (91) 16 m | 1986-2011 | Not mentioned | Bu Cy Mel | Not mentioned | Ac GVHD 48% | 59% (72 m) [69] |

| +- Serotherapy | ||||||

| (129) 24 m | 2000-2011 | PB = 10 | Bu Flu Mel in 59 | TAC+MTX in 73 | Gr II-IV Ac GVHD = 44% | 64% (5 y) [70] |

| BM = 89 | Bu Cy Ara-c in22 | CSA+MTX in 22 | Chr GVHD = 37/107 | |||

| UCB = 30 | TBI based in 20 | |||||

| (MRD = 44 | ||||||

| UD = 85) |

(BM: bone marrow; PB: peripheral blood; UCB: umbilical cord blood; MRD: matched related donor; MUD: matched unrelated donor; MMUD: mismatched unrelated donor; UD: unrelated donor; Bu: busulfan; Cy: cyclophosphamide; Mel: melphalan; Etop: etoposite; ATG: antithymocyte globulin; Flu: fludarabine; TBI: total body irradiation; Ara-C: Cytarabine; CSA: cyclosporine-A; MMF: mycophenolate mofetil; MTX: methotrexate; TAC: tacrolimus; Mo Ab: monoclonal antibodies; Ac GVHD: Acute graft versus host disease; Ch GVHD: chronic GVHD; Gr: grade; HSCT: Hematopoietic stem cell transplant).

For the GVHD prophylaxis, cyclosporine A (CSA) and methotrexate (MTX) are most commonly employed in the setting of MFD. In the presence of an unrelated donor, ATG is added. The use of anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) is not associated with an increased risk of relapse, given that it has the potential to attenuate the graft versus leukemia (GVL) effect [13].

The lower age of transplant may be responsible for the low occurrence of GVHD in JMML transplants. The occurrence of grade I-III GVHD has been associated with better survival possibly due to a GVL effect. A low-intensity GVHD prophylaxis should be used in JMML children with aggressive disease (such as NF-1, somatic PTPN11, or NRAS mutations, age >4 years at diagnosis or with >20% blasts at the time of HSCT). More aggressive GVHD prophylaxis should be considered in children with less aggressive JMML. In the absence of acute GVHD, GVHD prophylaxis should be tapered and stopped between days 60 and 180 after HSCT [55].

Post-transplant monitoring and management of relapse

Post-transplant monitoring of donor-recipient chimerism can help identify the patients who are at risk of relapse. In the setting of falling donor chimerism, the rapid withdrawal of immunosuppression can be tried. If there is no response, then donor lymphocyte infusions (DLI) can be used. The patients at high risk of relapse are ones with age >4 y, NF- 1/PTPN-11 mutations, bone marrow blasts >20% at the onset, AML type genetic signature, or high methylation pattern of methylation studies. Persistent disease and relapse even after HSCT can occur in 26-58% of patients [65]. A second allogeneic HSCT from a different donor or the same donor using a less aggressive GVHD prophylaxis can be attempted in case of an overt relapse. A second transplant can salvage 33% of the patients [62]. Patel et al in 2014 published a series of 5 JMML patients who had relapsed after their initial HSCT. They were subsequently treated with a second HSCT from the original donors after a high dose of cytarabine and mitoxantrone based conditioning. All patients were alive at a median follow up of 199 m (88-246 m) with no evidence of JMML and no significant toxicity [65]. In between 1987-2003 out of 183 patients who received an allogeneic HSCT in a European study, 68 relapsed. Twenty-six of these went on to receive a second allograft. Most patients received a TBI based conditioning for the second HSCT. The same donor was employed in 19 patients. In patients with transplants from the same donor, the intensity of the GVHD prophylaxis was reduced. 43% of the patients in this cohort were alive after a median follow up of 3. 3y [66]. Chang et al in a series of JMML patients who had undergone a second HSCT found that the survival in this retrospective cohort was 54% after a median follow-up of 53 m [67].

HSCT should be the treatment of choice for JMML patients. It is the only modality to achieve a cure in JMML. Only some variants (germline mutations of NRAS, KRAS, or PTPN 11 mutations and few CBL mutation-positive JMML) can achieve spontaneous remission or remission with mild chemotherapy.

Novel and targeted approaches to the treatment of JMML

GM-CSF analogs with a point mutation at the receptor-binding site were found to inhibit JMML cells’ growth in mice model by causing a dose and time-dependent apoptosis. This approach may be tried for achieving a transient control clinically in a trial [68].

As the RAS/MAPK pathway is hyperactive in JMML, investigators have tried blocking post-translational modifications of RAS protein through inhibition of the enzyme farnesyltransferase. Dose-dependent response to farnesyltransferase inhibitors had been demonstrated in vitro but in clinical trials, they were not found beneficial [69].

Bisphosphonates can suppress the activation of RAS through the suppression of both farnesylation and geranylgeranylation. Zoledronic acid can inhibit the colony-forming activity of JMML precursor cells. Clinical validation of this approach is still lacking [70].

The palmitoylation/depalmitoylation cycle has been targeted to disrupt the RAS pathway, disrupting the GM-CSF sensitive colony-forming units’ growth. This is known to selectively target NRAS but the clinical benefits were minimal.

The targeting of the downstream effectors of the RAS pathway viz RAF/MEK/ERK and PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathways has shown promise lately. Preclinically MEK inhibition has been proven to restore normal hematopoiesis in NF-1 and KRAS mutant mice. The evaluation of trametinib which is a MEK inhibitor in the treatment of JMML children is underway in a trial [62]. Inhibition of mTOR signaling using rapamycin resulted in the mitigation of the JMML phenotype in PTPN11 mutated mice and to correct the characteristic hypersensitivity to GM-CSF of PTPN11 mutated JMML BM cells in culture [71].

Inhibition of Src kinase by dasatinib and inhibition of JAK2 by ruxolitinib is being explored for JMML. Ruxolitinib has been known to stabilize the disease in a few of the patients in which it has been tried. Combined inhibition of the pathways is more effective in pre-clinical models [72].

In pre-clinical studies, trabectedin by binding to the minor groove of DNA inhibits DNA repair mechanisms, modulates transcription, and increases apoptosis. It is known to cause selective depletion of the myelomonocytic lineage cells and is a potential antitumor agent for MDS/MPS, such as JMML [73].

SH2-containing inositol 5-phosphatase 1 (SHIP-1) negatively regulates the GM-CSF signaling. Retroviral-mediated transduction of SHIP-1 into CD34+ cells from JMML patients with KRAS or PTPN11 mutations lead to a reduction in myeloid proliferation. Cytotoxic T-cell-based immunotherapy has also been shown to recognize JMML cells in an HLA-restricted fashion and help control disease in preclinical models [74].

Prognostic factors in JMML

Patients of JMML who presents at a younger age, having normal Hb F, germline mutations, remission after HSCT, do good (standard risk) whereas patients presenting at an older age, having high HbF, somatic mutations, complex cytogenetics, AML genetics, refractory/relapse course after HSCT have a worse prognosis (high risk). A very few patients in standard risk undergo spontaneous regression. The prognostic factors of JMML have been shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Prognostic factors in JMML

| Standard risk | High risk |

|---|---|

| Young age | Older age of presentation |

| Normal HbF | High HbF |

| Peripheral blood and bone marrow blasts <20% | Peripheral blood and bone marrow blasts >20% |

| Germline NRAS, KRAS, and PTPN11 | NF-1 mutation |

| CBL mutation | somatic NRAS, KRAS, and PTPN11 mutation |

| Low methylation profile | High methylation profile |

| Monosomy 7 | Double RAS variants |

| Spontaneous regression (good prognosis) or resolution with minimal chemotherapy (good prognosis) | Complex cytogenetics AML genetic signatures |

| Remission after HSCT | Relapse after HSCT/refractory disease after HSCT |

JMML: Juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia; NF-1: Neurofibromin-1; CBL: Casitas B-lineage lymphoma; PTPN11: Protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor type; KRAS: Kirsten rat sarcoma; NRAS: Neuroblastoma rat sarcoma; HSCT: Hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

Conclusion

JMML is a MPS/MDN overlap disorder of the pediatric age group and is caused due to mutations in the RAS pathway genes. JMML in most cases is an aggressive disease. The common mimickers of JMML must be ruled out based on clinical findings and investigations. Mutation analysis may help in establishing the diagnosis in up to 90% of cases. The diagnosis of JMML is established after validation of criteria as laid down by the WHO. The role of pre HSCT treatment in altering the course of the disease is still uncertain and it can only serve as a transient bridging option. Very few patients may go into spontaneous remission or with minimal chemotherapy. Azacytidine is emerging as a promising agent in recent clinical trials to achieve hematological and molecular response in a subset of JMML patients. Allogeneic HSCT is the only curative option available for JMML to date. HSCT can approximately cure half of the patients. In those who relapse, a second HSCT may be offered and it can lead to a cure in about 33% of these patients. Novel therapies targeting the downstream effectors of the RAS pathway are being explored in pre-clinical and clinical models with the hope to improve survival.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

AKG has been sanctioned a grant for research on the genomic landscape of JMML from the Indian Council of Medical Research.

Abbreviations

- JMML

Juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia

- NF-1

Neurofibromin-1

- CBL

Casitas B-lineage lymphoma

- PTPN11

Protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor type

- RAS

Rat sarcoma

- KRAS

Kirsten rat sarcoma

- NRAS

Neuroblastoma rat sarcoma

- MDS

Myelodysplastic syndrome

- MPN

Myeloproliferative neoplasm

- NS

Noonan syndrome

- HbF

Hemoglobin F

- BM

Bone marrow

- PB

Peripheral blood

- UBC

Umbilical cord blood

- GM-CSF

Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- HSCT

Hematopoietic stem cell transplant

- MUD

Matched unrelated donor

- MRD

Matched related donor

References

- 1.Chan RJ, Cooper T, Kratz CP, Weiss B, Loh ML. Juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia: a report from the 2nd international JMML symposium. Leuk Res. 2009;33:355–362. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Emanuel PD. Juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Curr Hematol Rep. 2004;3:203–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Childhood Acute Myeloid Leukemia/Other Myeloid Malignancies Treatment (PDQ®) - PDQ Cancer Information Summaries - NCBI Bookshelf [Internet]. [cited 2020 Sep 11] Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK66019/

- 4.Cseh A, Niemeyer CM, Yoshimi A, Dworzak M, Hasle H, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Locatelli F, Masetti R, Schmugge M, Groß-Wieltsch U, Candás A, Kulozik AE, Olcay L, Suttorp M, Furlan I, Strahm B, Flotho C. Bridging to transplant with azacitidine in juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia: a retrospective analysis of the EWOG-MDS study group. Blood. 2015;125:2311–2313. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-01-619734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Niemeyer CM, Arico M, Basso G, Biondi A, Cantu Rajnoldi A, Creutzig U, Haas O, Harbott J, Hasle H, Kerndrup G, Locatelli F, Mann G, Stollmann-Gibbels B, van’t Veer-Korthof ET, van Wering E, Zimmermann M. Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia in childhood: a retrospective analysis of 110 cases. European Working Group on Myelodysplastic Syndromes in Childhood (EWOG-MDS) Blood. 1997;89:3534–3543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Emanuel PD. Myelodysplasia and myeloproliferative disorders in childhood: an update. Br J Haematol. 1999;105:852–863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sasaki H, Manabe A, Kojima S, Tsuchida M, Hayashi Y, Ikuta K, Okamura J, Koike K, Ohara A, Ishii E, Komada Y, Hibi S, Nakahata T. Myelodysplastic syndrome in childhood: a retrospective study of 189 patients in Japan. Leukemia. 2001;15:1713–1720. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeBella K, Szudek J, Friedman JM. Use of the National Institutes of Health criteria for diagnosis of neurofibromatosis 1 in children. Pediatrics. 2000;105:608–614. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.3.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stiller CA, Chessells JM, Fitchett M. Neurofibromatosis, and childhood leukemia/lymphoma: a population-based UKCCSG study. Br J Cancer. 1994;70:969–72. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1994.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bader-Meunier B, Tchernia G, Mielot F, Fontaine JL, Thomas C, Lyonnet S, Lavergne JM, Dommergues JP. Occurrence of myeloproliferative disorder in patients with Noonan syndrome. J Pediatr. 1997;130:885–889. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)70273-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tartaglia M, Mehler EL, Goldberg R, Zampino G, Brunner HG, Kremer H, van der Burgt I, Crosby AH, Ion A, Jeffery S, Kalidas K, Patton MA, Kucherlapati RS, Gelb BD. Mutations in PTPN11, encoding the protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2, cause Noonan syndrome. Nat Genet. 2001;29:465–468. doi: 10.1038/ng772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tartaglia M, Pennacchio LA, Zhao C, Yadav KK, Fodale V, Sarkozy A, Pandit B, Oishi K, Martinelli S, Schackwitz W, Ustaszewska A, Martin J, Bristow J, Carta C, Lepri F, Neri C, Vasta I, Gibson K, Curry CJ, Siguero JP, Digilio MC, Zampino G, Dallapiccola B, Bar-Sagi D, Gelb BD. Gain-of-function SOS1 mutations cause a distinctive form of Noonan syndrome. Nat Genet. 2007;39:75–79. doi: 10.1038/ng1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberts AE, Araki T, Swanson KD, Montgomery KT, Schiripo TA, Joshi VA, Li L, Yassin Y, Tamburino AM, Neel BG, Kucherlapati RS. Germline gain-of-function mutations in SOS1 cause Noonan syndrome. Nat Genet. 2007;39:70–74. doi: 10.1038/ng1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schubbert S, Zenker M, Rowe SL, Boll S, Klein C, Bollag G, van der Burgt I, Musante L, Kalscheuer V, Wehner LE, Nguyen H, West B, Zhang KY, Sistermans E, Rauch A, Niemeyer CM, Shannon K, Kratz CP. Germline KRAS mutations cause Noonan syndrome. Nat Genet. 2006;38:331–336. doi: 10.1038/ng1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pandit B, Sarkozy A, Pennacchio LA, Carta C, Oishi K, Martinelli S, Pogna EA, Schackwitz W, Ustaszewska A, Landstrom A, Bos JM, Ommen SR, Esposito G, Lepri F, Faul C, Mundel P, López Siguero JP, Tenconi R, Selicorni A, Rossi C, Mazzanti L, Torrente I, Marino B, Digilio MC, Zampino G, Ackerman MJ, Dallapiccola B, Tartaglia M, Gelb BD. Gain-of-function RAF1 mutations cause Noonan and LEOPARD syndromes with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1007–1012. doi: 10.1038/ng2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Emanuel PD, Bates LJ, Castleberry RP, Gualtieri RJ, Zuckerman KS. Selective hypersensitivity to granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor by juvenile chronic myeloid leukemia hematopoietic progenitors. Blood. 1991;77:925–929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caye A, Strullu M, Guidez F, Cassinat B, Gazal S, Fenneteau O, Lainey E, Nouri K, Nakhaei-Rad S, Dvorsky R, Lachenaud J, Pereira S, Vivent J, Verger E, Vidaud D, Galambrun C, Picard C, Petit A, Contet A, Poirée M, Sirvent N, Méchinaud F, Adjaoud D, Paillard C, Nelken B, Reguerre Y, Bertrand Y, Häussinger D, Dalle JH, Ahmadian MR, Baruchel A, Chomienne C, Cave H. Juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia displays mutations in components of the RAS pathway and the PRC2 network. Nat Genet. 2015;47:1334–1340. doi: 10.1038/ng.3420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flotho C, Valcamonica S, Mach-Pascual S, Schmahl G, Corral L, Ritterbach J, Hasle H, Arico M, Biondi A, Niemeyer CM. RAS mutations and clonality analysis in children with juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML) Leukemia. 1999;13:32–37. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bourne HR, Sanders DA, McCormick F. The GTPase superfamily: a conserved switch for diverse cell functions. Nature. 1990;348:125–132. doi: 10.1038/348125a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsuda K, Shimada A, Yoshida N, Ogawa A, Watanabe A, Yajima S, Iizuka S, Koike K, Yanai F, Kawasaki K, Yanagimachi M, Kikuchi A, Ohtsuka Y, Hidaka E, Yamauchi K, Tanaka M, Yanagisawa R, Nakazawa Y, Shiohara M, Manabe A, Kojima S, Koike K. Spontaneous improvement of hematologic abnormalities in patients having juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia with specific RAS mutations. Blood. 2007;109:5477–5480. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-046649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tartaglia M, Niemeyer CM, Fragale A, Song X, Buechner J, Jung A, Hahlen K, Hasle H, Licht JD, Gelb BD. Somatic mutations in PTPN11 in juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia, myelodysplastic syndromes, and acute myeloid leukemia. Nat Genet. 2003;34:148–150. doi: 10.1038/ng1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan RJ, Feng GS. PTPN11 is the first identified proto-oncogene that encodes a tyrosine phosphatase. Blood. 2007;109:862–867. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-028829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu GF, OConnell P, Viskochil D, Cawthon R, Robertson M, Culver M, Dunn D, Stevens J, Gesteland R, White R, Weiss R. The neurofibromatosis type 1 gene encodes a protein related to GAP. Cell. 1990;62:599–608. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castro-Malaspina H, Schaison G, Passe S, Pasquier A, Berger R, Bayle-Weisgerber C, Miller D, Seligmann M, Bernard J. Subacute and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia in children (juvenile CML). Clinical and hematologic observations and identification of prognostic factors. Cancer. 1984;54:675–686. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1984)54:4<675::aid-cncr2820540415>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Side LE, Emanuel PD, Taylor B, Franklin J, Thompson P, Castleberry RP, Shannon KM. Mutations of the NF1 gene in children with juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia without clinical evidence of neurofibromatosis, type 1. Blood. 1998;92:267–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steinemann D, Arning L, Praulich I, Stuhrmann M, Hasle H, Stary J, Schlegelberger B, Niemeyer CM, Flotho C. Mitotic recombination and compound-heterozygous mutations are predominant NF1-inactivating mechanisms in children with juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia and neurofibromatosis type 1. Haematologica. 2010;95:320–323. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.010355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shannon KM, OConnell P, Martin GA, Paderanga D, Olson K, Dinndorf P, McCormick F. Loss of the normal NF1 allele from the bone marrow of children with type 1 neurofibromatosis, and malignant myeloid disorders. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:597–601. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199403033300903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Messiaen LM, Callens T, Mortier G, Beysen D, Vandenbroucke I, Van Roy N, Speleman F, Paepe AD. Exhaustive mutation analysis of the NF1 gene allows the identification of 95% of mutations and reveals a high frequency of unusual splicing defects. Hum Mutat. 2000;15:541–555. doi: 10.1002/1098-1004(200006)15:6<541::AID-HUMU6>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niemeyer CM, Kang MW, Shin DH, Furlan I, Erlacher M, Bunin NJ, Bunda S, Finklestein JZ, Gorr TA, Mehta P, Schmid I, Kropshofer G, Corbacioglu S, Lang PJ, Klein C, Schlegel PG, Heinzmann A, Schneider M, Starý J, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Hasle H, Locatelli F, Sakai D, Archambeault S, Chen L, Russell RC, Sybingco SS, Ohh M, Braun BS, Flotho C, Loh ML. Germline CBL mutations cause developmental abnormalities and predispose to juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2010;42:794–800. doi: 10.1038/ng.641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakashita K, Matsuda K, Koike K. Diagnosis and treatment of juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Pediatr Int. 2016;58:681–690. doi: 10.1111/ped.13068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caye A, Rouault-Pierre K, Strullu M, Lainey E, Abarrategi A, Fenneteau O, Arfeuille C, Osman J, Cassinat B, Pereira S, Anjos-Afonso F, Currie E, Ariza-McNaughton L, Barlogis V, Dalle JH, Baruchel A, Chomienne C, Cave H, Bonnet D. Despite mutation acquisition in hematopoietic stem cells, JMML-propagating cells are not always restricted to this compartment. Leukemia. 2020;34:1658–1668. doi: 10.1038/s41375-019-0662-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lipka DB, Witte T, Toth R, Yang J, Wiesenfarth M, Nollke P, Fischer A, Brocks D, Gu Z, Park J, Strahm B, Wlodarski M, Yoshimi A, Claus R, Lubbert M, Busch H, Boerries M, Hartmann M, Schonung M, Kilik U, Langstein J, Wierzbinska JA, Pabst C, Garg S, Catala A, De Moerloose B, Dworzak M, Hasle H, Locatelli F, Masetti R, Schmugge M, Smith O, Stary J, Ussowicz M, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Assenov Y, Schlesner M, Niemeyer C, Flotho C, Plass C. RAS-pathway mutation patterns define epigenetic subclasses in juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Nat Commun. 2017;8:2126. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02177-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Honda Y, Tsuchida M, Zaike Y, Masunaga A, Yoshimi A, Kojima S, Ito M, Kikuchi A, Nakahata T, Manabe A. Clinical characteristics of 15 children with juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia who developed blast crisis: MDS Committee of Japanese Society of Paediatric Haematology/Oncology. Br J Haematol. 2014;165:682–687. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Braun BS, Tuveson DA, Kong N, Le DT, Kogan SC, Rozmus J, Le Beau MM, Jacks TE, Shannon KM. Somatic activation of oncogenic Kras in hematopoietic cells initiates a rapidly fatal myeloproliferative disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:597–602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307203101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chan IT, Kutok JL, Williams IR, Cohen S, Kelly L, Shigematsu H, Johnson L, Akashi K, Tuveson DA, Jacks T, Gilliland DG. Conditional expression of oncogenic K-ras from its endogenous promoter induces a myeloproliferative disease. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:528–538. doi: 10.1172/JCI20476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Urs L, Stevens L, Kahwash SB. Leukemia presenting as solid tumors: report of four pediatric cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2008;11:370–376. doi: 10.2350/07-08-0326.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liy-Wong C, Mohammed J, Carleton A, Pope E, Parkin P, Lara-Corrales I. The relationship between neurofibromatosis type 1, juvenile xanthogranuloma, and malignancy: a retrospective case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:1084–1087. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lorenzana A, Lyons H, Sawaf H, Higgins M, Carrigan D, Emanuel PD. Human herpesvirus 6 infection mimicking juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia in an infant. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2002;24:136–141. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200202000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Janik-Moszant A, Barc-Czarnecka M, van der Burg M, Langerak AW, Hartwig NG, Vossen AC, Niemeyer CM, Wachowiak J, Sońta-Jakimczyk D, Szczepanski T. Concomitant EBV-related B-cell proliferation and juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia in a 2-year-old child. Leuk Res. 2008;32:181–184. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strauss A, Furlan I, Steinmann S, Buchholz B, Kremens B, Rossig C, Corbacioglu S, Rajagopal R, Lahr G, Yoshimi A, Strahm B, Niemeyer CM, Schulz A. Unmistakable morphology? Infantile malignant osteopetrosis resembling juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia in infants. J Pediatr. 2015;167:486–488. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.04.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rottgers S, Gombert M, Teigler-Schlegel A, Busch K, Gamerdinger U, Slany R, Harbott J, Burkhardt A. ALK fusion genes in children with atypical myeloproliferative leukemia. Leukemia. 2010;24:1197–1200. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stieglitz E, Liu YL, Emanuel PD, Castleberry RP, Cooper TM, Shannon KM, Loh ML. Mutations in GATA2 are rare in juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Blood. 2014;123:1426–1427. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-11-531079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Borkhardt A, Bojesen S, Haas OA, Fuchs U, Bartelheimer D, Loncarevic IF, Bohle RM, Harbott J, Repp R, Jaeger U, Viehmann S, Henn T, Korth P, Scharr D, Lampert F. The human GRAF gene is fused to MLL in a unique t(5;11) (q31;q23) and both alleles are disrupted in three cases of Myelodysplastic Syndrome/acute myeloid leukemia with a Deletion 5q. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:9168–9173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.150079597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Niemeyer CM. RAS diseases in children. Haematologica. 2014;99:1653–1662. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2014.114595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kratz CP, Niemeyer CM, Castleberry RP, Cetin M, Bergstrasser E, Emanuel PD, Hasle H, Kardos G, Klein C, Kojima S, Stary J, Trebo M, Zecca M, Gelb BD, Tartaglia M, Loh ML. The mutational spectrum of PTPN11 in juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia and Noonan syndrome/myeloproliferative disease. Blood. 2005;106:2183–2185. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Strullu M, Caye A, Lachenaud J, Cassinat B, Gazal S, Fenneteau O, Pouvreau N, Pereira S, Baumann C, Contet A, Sirvent N, Mechinaud F, Guellec I, Adjaoud D, Paillard C, Alberti C, Zenker M, Chomienne C, Bertrand Y, Baruchel A, Verloes A, Cave H. Juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia and Noonan syndrome. J Med Genet. 2014;51:689–697. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2014-102611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.O Halloran K, Ritchey AK, Djokic M, Friehling E. Transient juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia in the setting of PTPN11 mutation and Noonan syndrome with secondary development of monosomy 7. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64:e26408. doi: 10.1002/pbc.26408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Locatelli F, Nollke P, Zecca M, Korthof E, Lanino E, Peters C, Pession A, Kabisch H, Uderzo C, Bonfim CS, Bader P, Dilloo D, Stary J, Fischer A, Revesz T, Fuhrer M, Hasle H, Trebo M, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Fenu S, Strahm B, Giorgiani G, Bonora MR, Duffner U, Niemeyer CM European Working Group on Childhood MDS; European Blood and Marrow Transplantation Group. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) in children with juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML): results of the EWOG-MDS/EBMT trial. Blood. 2005;105:410–419. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Proytcheva M. Juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2011;28:298–303. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moritake H, Ikeda T, Manabe A, Kamimura S, Nunoi H. Cytomegalovirus infection mimicking juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia showing hypersensitivity to granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;53:1324–1326. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hasegawa D, Bugarin C, Giordan M, Bresolin S, Longoni D, Micalizzi C, Ramenghi U, Bertaina A, Basso G, Locatelli F, Biondi A, TeKronnie G, Gaia G. Validation of flow cytometric phospho-STAT5 as a diagnostic tool for juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Blood Cancer J. 2013;3:e160. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2013.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ramzan M, Yadav SP, Dhingra N, Sachdeva A. Juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia in India: cure remains a distant dream! Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. 2014;30:398–401. doi: 10.1007/s12288-014-0434-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bergstraesser E, Hasle H, Rogge T, Fischer A, Zimmermann M, Noellke P, Niemeyer CM. Non-hematopoietic stem cell transplantation treatment of juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia: a retrospective analysis and definition of response criteria. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;49:629–633. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wajid M A, Gupta AK, Das G, Sahoo D, Meena JP, Seth R. Outcomes of juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia patients after sequential therapy with cytarabine and 6-mercaptopurine. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2020;37:1–9. doi: 10.1080/08880018.2020.1767244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Locatelli F, Niemeyer CM. How I treat juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Blood. 2015;125:1083–1090. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-08-550483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Furlan I, Batz C, Flotho C, Mohr B, Lubbert M, Suttorp M, Niemeyer CM. Intriguing response to azacitidine in a patient with juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia and monosomy 7. Blood. 2009;113:2867–2868. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-195693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fabri O, Horakova J, Bodova I, Svec P, LaluhovaStriezencova Z, Bubanska E, Cermak M, Galisova V, Skalicka K, Vaska A, Doczyova D, Panikova A, Sykora T, Adamcakova J, Kolenova A. Diagnosis and treatment of juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia in the Slovak Republic: novel approaches. Neoplasma. 2019;66:818–824. doi: 10.4149/neo_2018_181231N1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hashmi SK, Punia JN, Marcogliese AN, Gaikwad AS, Fisher KE, Roy A, Rao P, Lopez-Terrada DH, Ringrose J, Loh ML, Niemeyer CM, Rau RE. Sustained remission with azacitidine monotherapy and an aberrant precursor B-lymphoblast population in juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2019;66:e27905. doi: 10.1002/pbc.27905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ozyurek E, Çetin M, Tuncer M, Hicsonmez G. The role of splenectomy in children with juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Turk J Pediatr. 2007;49:154–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Smith FO, King R, Nelson G, Wagner JE, Robertson KA, Sanders JE, Bunin N, Emaunel PD, Davies SM National Marrow Donor Program. Unrelated donor bone marrow transplantation for children with juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Br J Haematol. 2002;116:716–724. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1048.2001.03333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Locatelli F, Crotta A, Ruggeri A, Eapen M, Wagner JE, Macmillan ML, Zecca M, Kurtzberg J, Bonfim C, Vora A, Díaz de Heredia C, Teague L, Stein J, O Brien TA, Bittencourt H, Madureira A, Strahm B, Peters C, Niemeyer C, Gluckman E, Rocha V. Analysis of risk factors influencing outcomes after cord blood transplantation in children with juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia: a EURO CORD, EBMT, EWOG-MDS, CIBMTR study. Blood. 2013;122:2135–2141. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-03-491589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Locatelli F, Algeri M, Merli P, Strocchio L. Novel approaches to diagnosis and treatment of Juvenile Myelomonocytic Leukemia. Expert Rev Hematol. 2018;11:129–143. doi: 10.1080/17474086.2018.1421937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Meyran D, Porcher R, Raus N, Strullu M, Ouache M, Yakouben K, Galambrun C, Neven B, Lutz P. Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (HSCT) for Juvenile Myelomonocytic Leukemia (JMML) in France: a retrospective study of Société Française De Greffe De Moelle Et De ThérapieCellulaire. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19:S163. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yoshida N, Sakaguchi H, Yabe M, Hasegawa D, Hama A, Hasegawa D, Kato M, Noguchi M, Terui K, Takahashi Y, Cho Y, Sato M, Koh K, Kakuda H, Shimada H, Hashii Y, Sato A, Kato K, Atsuta Y, Watanabe K. Pediatric myelodysplastic syndrome working group of the Japan society for hematopoietic cell transplantation. Clinical outcomes after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in children with juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia: a report from the Japan society for hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2020;26:902–910. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2019.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Patel SA, Coulter DW, Grovas AC, Gordon BG, Harper JL, Warkentin PI, Wisecarver JL, Sanger WG, Coccia PF. Cytosine arabinoside and mitoxantrone followed by second allogeneic transplant for the treatment of children with refractory juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2014;36:491–494. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000000077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yoshimi A, Bader P, Matthes-Martin S, Stary J, Sedlacek P, Duffner U, Klingebiel T, Dilloo D, Holter W, Zintl F, Kremens B, Sykora KW, Urban C, Hasle H, Korthof E, Revesz T, Fischer A, Nöllke P, Locatelli F, Niemeyer CM. European Working Group of MDS in Childhood (EWOG-MDS). Donor leukocyte infusion after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2005;19:971–977. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chang YH, Jou ST, Lin DT, Lu MY, Lin KH. Second allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia: case report and literature review. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2004;26:190–193. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200403000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bernard F, Thomas C, Emile JF, Hercus T, Cassinat B, Chomienne C, Donadieu J. Transient hematologic and clinical effect of E21R in a child with end-stage juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Blood. 2002;99:2615–2616. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.7.2615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Castleberry RP, Loh ML, Jayaprakash N, Peterson AP, Casey V, Chang M, Widemann B, Emanuel P. Phase II window study of the farnesyltransferase inhibitor R115777 (Zarnestra) (R) in untreated juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML): a children’s oncology group study. Blood. 2005;106:727A–728A. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ohtsuka Y, Manabe A, Kawasaki H, Hasegawa D, Zaike Y, Watanabe S, Tanizawa T, Nakahata T, Tsuji K. RAS-blocking bisphosphonate zoledronic acid inhibits the abnormal proliferation and differentiation of juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia cells in vitro. Blood. 2005;106:3134–3141. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-0972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liu W, Yu WM, Zhang J, Chan RJ, Loh ML, Zhang Z, Bunting KD, Qu CK. Inhibition of the Gab2/PI3K/mTOR signaling ameliorates myeloid malignancy caused by Ptpn11 (Shp2) gain-of-function mutations. Leukemia. 2017;31:1415–1422. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Loh ML, Tasian SK, Rabin KR, Brown P, Magoon D, Reid JM, Chen X, Ahern CH, Weigel BJ, Blaney SM. A phase 1 dosing study of ruxolitinib in children with relapsed or refractory solid tumors, leukemias, or myeloproliferative neoplasms: a children’s oncology group phase 1 consortium study (ADVL1011) Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62:1717–1724. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Romano M, Della Porta MG, Galli A, Panini N, Licandro SA, Bello E, Craparotta I, Rosti V, Bonetti E, Tancredi R, Rossi M, Mannarino L, Marchini S, Porcu L, Galmarini CM, Zambelli A, Zecca M, Locatelli F, Cazzola M, Biondi A, Rambaldi A, Allavena P, Erba E, D’Incalci M. Antitumour activity of trabectedin in myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasms. Br J Cancer. 2017;116:335–343. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2016.424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Koike K, Matsuda K. Recent advances in the pathogenesis and management of juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Br J Haematol. 2008;141:567–575. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Manabe A, Okamura J, Yumura-Yagi K, Akiyama Y, Sako M, Uchiyama H, Kojima S, Koike K, Saito T, Nakahata T MDS Committee of the Japanese Society of Pediatric Hematology. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for 27 children with juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia diagnosed based on the criteria of the International JMML Working Group. Leukemia. 2002;16:645–649. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]