Highlights

-

•

Cutaneous adnexal neoplasms are calcified according to the skin appendage origin.

-

•

Clinical diagnosis is impossible. Thus, surgical excision is always required.

-

•

Pathological examination is generally adequate for their correct classification.

-

•

Trichilemmal carcinoma is a malignant cutaneous adnexal neoplasm of hair follicles.

-

•

Trichilemmal carcinoma is a rare tumour, mainly when located in the axilla.

Keywords: Cutaneous adnexal neoplasms, Trichilemmal carcinoma, Metastasis, Wide excision

Abstract

Introduction and importance

Trichilemmal carcinoma is a rare malignant cutaneous adnexal neoplasm of hair follicles originating from the external root sheath epithelium. The diagnosis is rarely made clinically and is still challenging for an experienced pathologist.

Aim

To report a rare case of trichilemmal carcinoma presenting as a right axillary mass with regional lymph nodes metastasis and was treated with wide local excision in the General Surgery Department Jordanian Royal Medical Services (JRMS), Jordan.

Case presentation

A 45-year-old presented with a right axillary mass of six-month duration. Physical examination revealed a hyperemic, thickened skin of both armpits with a palpable 5-cm mass in the right axilla. He underwent an excisional biopsy of the right mass. Histopathologic examination revealed a malignant adnexal skin tumour with foci of trichilemmal-type keratinisation. It was excised with adequate margins.

Clinical discussion

Trichilemmal carcinoma usually occurs on the forehead, scalp, neck, back of hands and trunk. These neoplasms are rare lesions presenting as locally aggressive, low-grade carcinomas and have the potential for nodal involvement and distant metastasis. Therefore, the establishment of a correct diagnosis is vital to guide the treatment plan. Wide excision with adequate tumour-free margins is considered a curative treatment and offers a successful outcome.

Conclusion

Malignant cutaneous adnexal tumours are one of the most challenging subjects of dermatopathology. Surgical excision is always required to establish a definitive diagnosis and differentiation subtypes. Trichilemmal carcinoma is a relatively rare tumour, mainly when located in the axilla.

1. Introduction

Cutaneous adnexal neoplasms are a variety of benign and malignant neoplasms in one of the skin's essential adnexal structures. Most of them are benign, and surgical excision is curative. The diagnosis is rarely made on a clinical basis and is still challenging for an experienced pathologist. They are usually encountered as solitary, sporadic tumours. However, multiple and hereditary lesions were reported. Associated clinical syndromes include visceral neoplasms, sebaceous tumours and trichilemmomas. The clinical presentation of these tumours is usually non-specific. Excisional biopsy is required to establish the definitive diagnosis, the histological morphology and differentiation subtypes. A routine pathological examination is generally appropriate for their correct classification, but histochemical and immunohistochemical stains may sometimes serve as ancillary tools [[1], [2], [3]]. Trichilemmal carcinoma is a malignant cutaneous adnexal neoplasm of hair follicles originating from the external root sheath epithelium. It is rare and affects sun-exposed skin areas predominantly in elderly subjects and usually curable after a wide local excision [4].

We reported our experience in the General Surgery department in the Jordanian Royal Medical Services (JRMS), Amman, Jordan, with a trichilemmal carcinoma presenting as a right axillary mass with regional lymph nodes metastasis treated with wide local excision. This case report has been reported in line with the SCARE 2020 Criteria [5].

2. Case report

A 45-year-old male was referred from an internal medicine clinic to the surgical clinic in September 2015 to assess a suspicious mass on his right axilla. He presented with a firm, large right axillary mass with overlying skin thickening and purulent discharge of six-month duration. He denied fever, chills, upper respiratory tract infection symptoms, and appetite or weight change. He had a family history of lymphoma, which affected his brother at the age of 28. The patient reported that he had prolonged use of topical skin preparation for hair removal on both armpits.

The patient reported no chronic disease and took no regular medications. He was married, had no recent travel history, denied unusual exposure to livestock or birds and had no known tuberculosis exposure. He reported smoking 1.5 packs of cigarettes per day for 15 years and reported drinking 3 cups of caffeinated beverages each morning. Additional family history was unremarkable. No drug allergies documented.

Clinical examination revealed a man with good body-built. No visible jaundice or signs of wasting was noticed. Head and neck examination was negative for other lymphadenopathy sites or any other signs of chronic systemic disease. An axillary exam showed a hyperemic, thickened skin of the right axilla with a palpable 5-cm irregular mass. The left axilla showed inflammatory changes, including redness, hotness and tenderness with a persistently discharging sinus. Examination of his chest revealed normal symmetrical lung expansion and adequate air entry on both lungs. His cardiovascular system study had no pathological signs. The abdominal examination had not detected any masses, organomegaly or other abnormalities, and no extremity swelling was present.

Laboratory studies, including complete blood count (CBC), kidney function and electrolytes, and liver function tests, were within normal limits. Albumin level was 3.7 g/dL. Neck, chest and abdominal CT scan demonstrated a group of matted right axillary lymph nodes measuring 5.0 × 2.5 cm with central necrosis features. The left axilla had evidence of small skin thickening without definitive masses. Otherwise, no cervical, hilar, mediastinal or intra-abdominal lymph node enlargement, or focal lung masses or pleural effusion were detected. The radiologic features suggested the diagnosis of tuberculosis (TB) and, less likely, lymphoma.

As the patient had no history of contact with tuberculosis patients and had a negative tuberculin skin test, the diagnosis of lymphoma was put on the top of the differential diagnosis list. The patient was referred from the primary physician to our surgical clinic for excisional biopsy. The patient underwent an excisional biopsy of the right mass. Intraoperatively, the mass was composed of matted lymph nodes with a "suspicious" appearance. The histopathological examination revealed the presence of malignant adnexal skin tumour composed of lobules and trabeculae of atypical keratinocytes exhibiting clear cell change with foci of trichilemmal-type keratinisation associated with atypia and tumour necrosis (Figs. 1 & 2). Some lobules showed peripheral palisading of the keratinocytes (Fig. 3). The cells exhibited marked pleomorphism and numerous mitoses (Fig. 4). Immunohistochemical tests were performed to clarify the origin of the tumour cells. Cytokeratin 5/6 immunostain was strongly positive (Fig. 5), whereas the negativity of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) immunostain (Fig. 6) distinguished it from different eccrine carcinoma or basal cell carcinoma. The features were consistent with trichilemmal carcinoma invading the adjacent lymph nodes. It was excised with a safety margin of less than 1 mm. He underwent fine-needle aspiration form the left axillary thickening skin and showed multiple foci of acute and chronic inflammation without evidence of malignancy. The Completion excision for the tumour was performed with an excellent oncologic outcome.

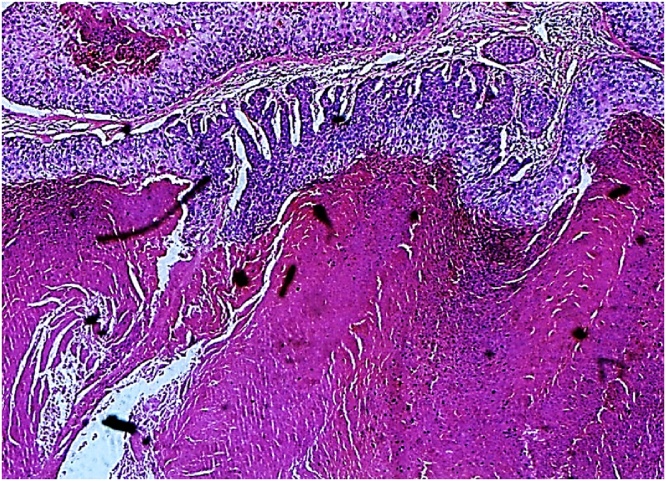

Fig. 1.

Histopathology (HE staining, 100×) Trichilemmal keratinization.

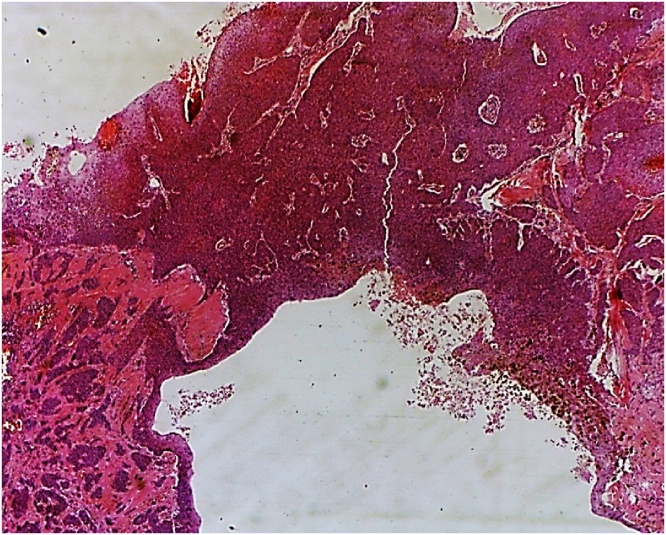

Fig. 2.

Histopathology (HE staining, 40×) Trichilemmal carcinoma; infiltrative sheets of malignant cells with desmoplastic stroma.

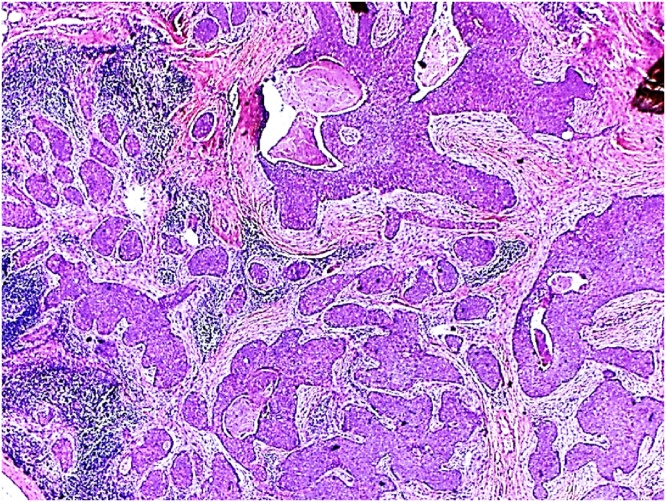

Fig. 3.

Histopathology (HE staining, 40×) Trichilemmal carcinoma; composed of multiple sheet of malignant cells showing peripheral pallisading and trichelimmal keratinization.

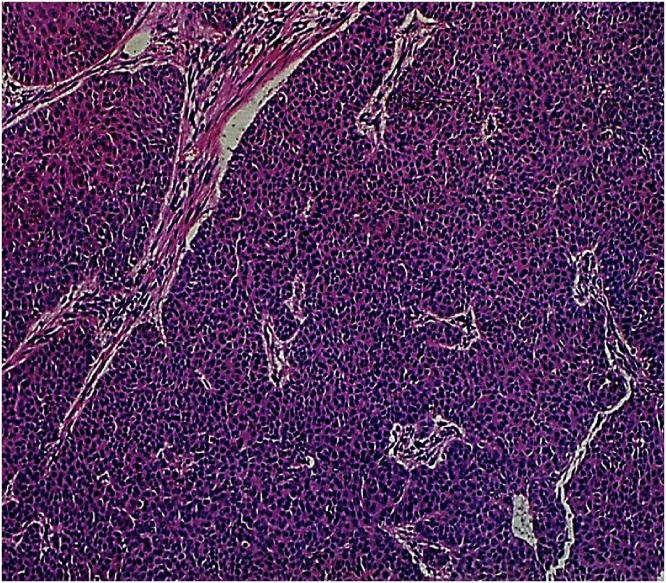

Fig. 4.

Histopathology (HE staining, 40×) Trichilemmal carcinoma; frequent mitotic activity.

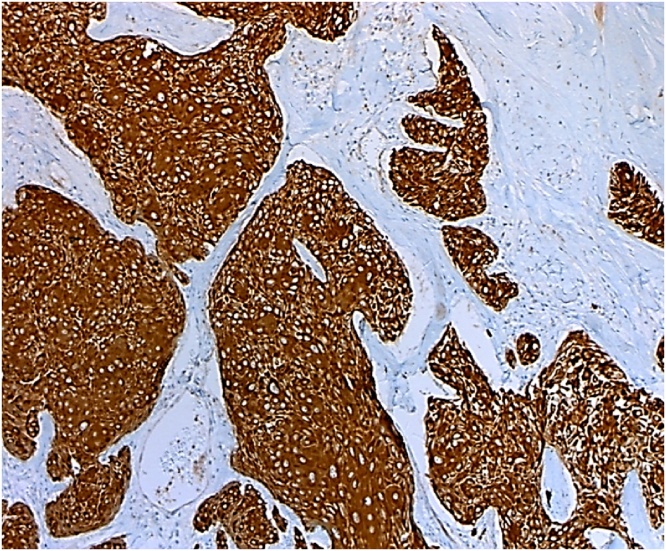

Fig. 5.

Histopathology: Cytokeratin 5/6 immunostain is strongly positive in the tumor cells.

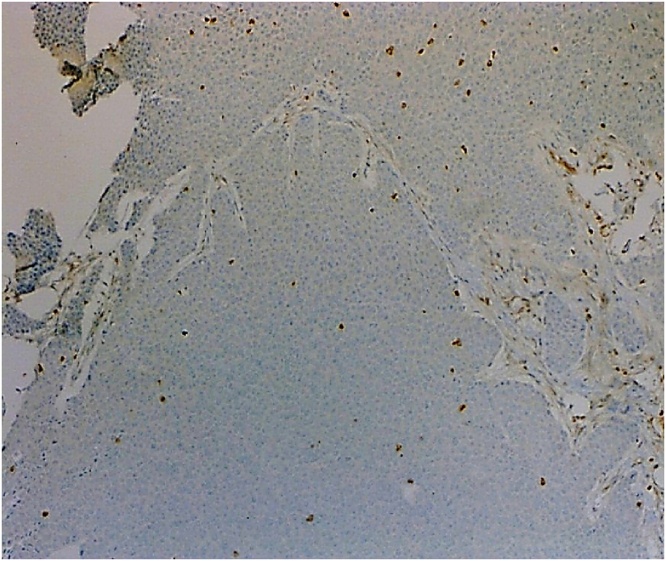

Fig. 6.

Histopathology: BCL-2 immunostain is negative in the tumor cells.

Follow-up with PET scan was the management plan, in the absence of palpable masses in the left axilla. The skin thickening in the left armpit remained stable on a follow-up PET scan over eight months, favouring the diagnosis of a benign pathologic process in the left armpit. By this time, the patient has completed two years of surgical care and follow-up without reporting any complications, local recurrence or distance metastasis.

3. Discussion

Skin appendages are developed early during the fourth week of embryological life and derived from the ectoderm. Histologically, skin appendages are represented by three distinct structures: The pilosebaceous unit, the eccrine sweat glands, and the apocrine glands. Histologically, the pilosebaceous units are composed of a hair follicle and sebaceous glands. The hair follicle is a highly modified keratinised structure and formed from epithelial and mesenchymal compartments. The compartment of the epithelium includes the matrix, hair shaft, inner sheath and outer epithelial sheath. The compartment of the mesenchyme consists of the dermal sheath and dermal papilla. The sebaceous gland consists of multiple lobules epithelial cell, called sebocytes, filled with degenerated sebocytes' lipid content into the hair follicle. Developmentally, all sebaceous glands are hair follicle-dependent, except those of the glans penis and labia minora. Eccrine sweat glands are present on all human bodies, and the majority found in the palm and soles. In contrast to eccrine glands, apocrine glands are found mainly in the axillae, groin, pubic and perineal regions [[1], [2], [3], [4]].

Cutaneous adnexal neoplasms comprise a broad domain of benign and malignant neoplasms that show morphological differentiation towards one of the diverse types of adnexal structures existing in normal skin: pilosebaceous unit, eccrine sweat glands and apocrine glands. Most adnexal neoplasms are comparatively uncommonly encountered in clinical practice, and pathologists could recognize a limited number of frequently encountered tumours. In the cases of potential cutaneous adnexal neoplasms, clinical data useful to correctly classify the lesions includes patient's age, sex, locations of the lesion, tumour growth rate, whether the lesion is single or multiple, and, if present, any associated inherited or systemic diseases. These neoplasms are rare lesions presenting as locally aggressive, low-grade carcinomas and have the potential for nodal involvement and distant metastasis. Therefore, the establishment of a correct diagnosis of malignant cutaneous adnexal neoplasms is vital to guide the treatment plan [[1], [2], [3], [4]].

Trichilemmal carcinoma usually affects sun-exposed skin. The most commonly involved areas are the forehead, scalp, neck, back of hands and trunk. It is rarely located in the axilla [6]. The pathogenesis for trichilemmal carcinoma is not exact yet, but most patients had a history of significant lifetime sun exposure [6]. However, trichilemmal carcinoma has reported in immunosuppressed patients after renal transplantation, post-surgical radiation, in preexisting burn scars, and in an elderly male patient with a diagnosis of tuberculosis who received more than 50 diagnostic chest radiographs [[6], [7], [8]]. The present study shows a history of chronic exposure to minimally toxic doses of shaving powder which dissolves hair at the skin's surface on both armpits. Caustic ingredients can cause skin irritation or even chemical burns, leading to skin disease and cutaneous cancer.

Clinically, tumours may present as papules, nodules or plaques, frequently ulcerated or with crusts. The clinical characteristics of trichilemmal carcinoma are usually not taken into consideration. In most patients, the lesion was present for a prolonged time before diagnosis, and a recent rapid growth phase occurred [9]. Therefore the patient seeking a medical evaluation in the late stage of disease progression. Clinically, it may be misdiagnosed. Therefore, it must be differentiated from another skin neoplasm such as basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, nodular melanoma and invasive Bowen's disease [10].

Histologically, the tumours are purely intra-epithelial or are more commonly associated with an invasive component centred around the pilosebaceous unit, which may reach from the epidermis to subcutaneous fat. They are commonly continuous with the epidermis and the follicular epithelium. They have bleeding with or without necrosis focuses when they become more extensive. The diagnosis is confirmed following histopathological examination using hematoxylin and eosin staining, complemented by immunohistochemical staining of the lesions [9].

Differential diagnosis must be established with other skin tumours, like squamous cell carcinomas, basal cell carcinomas, eccrine carcinomas, trichilemmoma, and malignant nodular melanomas. Squamous cell carcinoma, clear cell type, lacks peripheral palisading and connective tissue sheath of trichilemmal differentiation. Squamous cell carcinomas typically show a more infiltrative invasive front. Eccrine carcinomas may sometimes show clear cell differentiation. Trichilemmoma or desmoplastic variants can show an infiltrative growth pattern. Remarkable pleomorphism and mitoses are absent in benign trichilemmoma.

The original article published in 2017 for ten years' consecutive analysis axillary biopsies sent to the pathology laboratory of a tertiary hospital in Nigeria were formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). They found that axillary masses' histologic evaluation will assist in the appropriate treatment of diseases and essential for a better outcome and avoiding complications, and minimising companion morbidity and mortality [11].

Wide local excision with adequate margins is considered a potentially curative treatment and offers a successful outcome. There is no other effective treatment strategies have yet been established for these neoplasms [12]. Generally, continuous or periodic surveillance without adjuvant therapy is adequate [7]. Zhuang SM et al. at The Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center between 1998 and 2012 evaluated the survival and clinicopathological characteristics of trichilemmal carcinoma. They found the critical prognostic factors affecting survival were adequate surgical margin and lymph node metastasis [13].

Our case report is remarkable for several reasons: (1) The scarcity of this pathological condition with a lake of risk factors such as a history of significant lifetime sun exposure, radiotherapy and burn scar. (2) The atypical site of a tumour in the axilla with a potential causal relationship to chronic skin damage by chemicals. (3) Wide local excision with tumour-free margins is effective for treating trichilemmal carcinoma without complications or local recurrence.

4. Conclusion

Malignant cutaneous adnexal tumours are one of the most challenging subjects of dermatopathology. Trichilemmal carcinoma is a malignant cutaneous adnexal tumour, and it is relatively rare, mainly when located in the axilla [1,2]. Diagnosis is impossible, clinically. Thus, surgical excision is always required. Lymph node metastasis and adequate surgical margin were the prognostic factors that influenced the treatment outcome. After surgical excision, local recurrence and metastasis are rare [[2], [3], [4]]. There is insufficient clinical data to establish a causal relationship between chronic exposure to shaving powder and long-term adverse effects on the skin.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None of the authors have conflicts of interest.

Sources of funding

This study has no sponsors and is self-funded.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval has been taken from The Ethical Committee at King Hussein Medical Center, Amman, Jordan. The reference number is 1/2/2021.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contribution

Category 1:

Interpretation of the CT images: Ishraq S. Abudarweesh.

Interpretation of the PET scan images: Eslam H. Jabali.

Pre-Operative care: Heba G. Dboush, Mohammad A. Al-Doud, Ahmad S. Alabbadi.

Operation:

Main Surgeon: Heba G. Dboush.

Assistants Surgeon: Mohammad A. Al-Doud.

Post-Operative Care: Heba G. Dboush, Mohammad A. Al-Doud, Ahmad S. Alabbadi.

Category 2:

Drafting the manuscript: Heba G. Dboush, Mohammad A. Al-Doud, Ruba Y. Shannaq.

Revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content: Heba G. Dboush, Mohammad A. Al-Doud, Ruba Y. Shannaq.

Category 3:

Approval of the version of the manuscript to be published (the names of all authors must be listed): Heba G. Dboush, Mohammad A. Al-Doud, Ruba Y. Shannaq, Ishraq S. Abudarweesh, Eslam H. Jabali, Ahmad S. Alabbadi.

Registration of research studies

Not applicable.

Guarantor

Dr. Heba G. Dboush.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Contributor Information

Heba G. Dboush, Email: Jordanian1@rocketmail.com.

Mohammad A. Al-Doud, Email: Mohammad.aldoud@yahoo.com.

Ruba Y. Shannaq, Email: Rubashannag@yahoo.com.

Ishraq S. Abudarweesh, Email: Ishraq.abudarweesh@yahoo.com.

Eslam H. Jabali, Email: Eslamjabali85@gmail.com.

Ahmad S. Alabbadi, Email: Abbadi_Ahmad@mail.ru.

References

- 1.Pasquali Paola, Baldi Alfonso, Spugnini Enrico. 2014. Skin Cancer A Practical Approach; pp. 89–95. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alsaad K.O., Obaidat N.A., Ghazarian D. Skin adnexal neoplasms--part 1: an approach to tumours of the pilosebaceous unit. J. Clin. Pathol. 2007;60:129. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2006.040337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Obaidat N.A., Alsaad K.O., Ghazarian D. Skin adnexal neoplasms--part 2: an approach to tumours of cutaneous sweat glands. J. Clin. Pathol. 2007;60:145. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2006.041608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Requena Luis, Sangüeza Omar. 2017. Cutaneous Adnexal Neoplasms; pp. 684–696. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agha R.A., Franchi T., Sohrabi C., Mathew G., for the SCARE Group The SCARE 2020 guideline: updating consensus surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2020;84:226–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu B., Wang T., Liao Z. Surgical treatment of trichilemmal carcinoma. World J. Oncol. 2018;9(5–6):141–144. doi: 10.14740/wjon1143w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ko T., Tada H., Hatoko M., Muramatsu T., Shirai T. Trichilemmal carcinoma developing in a burn scar: a report of two cases. J. Dermatol. 1996;23:463–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan K., Lim I., Baladas H., Tan W.T.L. Multiple tumour presentation of trichilemmal carcinoma. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 2000;52:665–667. doi: 10.1054/bjps.1999.3180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rao Shalinee. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumour presenting early in life: an uncommon feature. J. Cutan. Aesthet. Surg. 2011;vol. 4(1):51–55. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.79196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yanofsky Valerie R. Histopathological variants of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a review. J. Skin Cancer. 2011;vol. 2011:210813. doi: 10.1155/2011/210813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bello U., Omotara S.M. Spectrum of diseases in the axilla: a histopathological analysis of axillary masses. Niger J Basic Clin Sci. 2017;14:96–100. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiss J., Heine M., Grimmel M., Jung E.G. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal cyst. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1995;32:870–873. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(95)91550-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhuang S.M., Zhang G.H., Chen W.K. Survival study and clinicopathological evaluation of trichilemmal carcinoma. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2013;1(3):499–502. doi: 10.3892/mco.2013.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]