Highlights

-

•

Diagnosis and management of aggressive angiomyxoma may be challenging.

-

•

MRI with DWI can be considered as a diagnostic tool in aggressive angiomixoma.

-

•

Complete surgical resection in tertiary referral hospitals can be the best treatment option.

-

•

GNRH agonist as a preventive option from recurrence is helpful.

Abbreviations: GNRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone; AAM, aggressive angiomyxoma; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; DWI, diffusion-weighted imaging

Keywords: Aggressive angiomyxoma, GNRH, Case report, Surgical resection

Abstract

Introduction and importance

Aggressive angiomyxoma is characterized as a non-capsulated soft mass with the ability to progress to surrounding tissues but without metastasis to distant tissues. Slowing tumor extension leading delayed tumor diagnosis, expression of different types of hormonal receptors, therapeutic ineffectiveness of noninvasive treatment approaches and misdiagnosis have remained as the major challenges for managing this tumor.

Case presentation

Herein, we described a case of aggressive angiomyxoma located in the posterior of the uterus and vagina that as successfully managed surgically to remove tumor mass followed by gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist to prevent tumor recurrence.

Clinical discussion

Surgical resection is the treatment of choice in aggressive angiomyxoma with complete success rate, however despite such successfulness, about two-thirds of patients experienced postoperative recurrence rate that could be prevented by hormone-based therapy especially GnRH agonist.

Conclusion

Aggressive angiomyxoma is a rare tumor with locally invasive behavior. As misdiagnosis is common imaging like MRI with DWI should be considered. The best treatment is surgical resection by experienced surgeons in tertiary referral hospitals. Even with complete resection, the recurrence rate is high. So adjuvant medical treatment seems to be necessary.

1. Introduction

Aggressive angiomyxoma was described primarily in 1983 by Steeper and Rosai as a mesenchymal tumor located mainly in pelvis and perineum [1]. This tumor is characterized as a non-capsulated soft mass with the ability to progress to surrounding tissues but without metastasis to distant tissues [2]. In histological assessment, bland nuclei without any evidence of mitotic activity are prominent [3]. Due to the aggressive local recurrent behavior of this tumor, it is of particular clinical importance and its timely diagnosis and therapeutic management are very important. Herein, we described a case of aggressive angiomyxoma located in the posterior of the uterus and vagina that as successfully managed surgically to remove tumor mass followed by gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist to prevent tumor recurrence.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

This work has been reported in line with the SCARE 2020 criteria [4].

2. Case presentation

A 33-year-old G2P2L2 woman came to our hospital with a regular menstrual cycle, complaining of abdominal pain from about 1 year ago as well as problem in intercourse. No abnormality was reported in past medical history. There was also no report of familial disorders or receiving special medications. The patient had a history of two surgeries due to pelvic mass in the last year. Due to abdominal pain, the patient was scheduled for an ultrasound in which the dermoid mass was proposed and thus the patient underwent CT scanning of the abdomen, pelvis, and lungs about one year ago. On CT scan, a soft tissue mass with a diameter of 95 × 120 mm was seen in the pelvic area, behind the bladder with non-uniform enhancement with displacement of the uterus and bladder to anterior and rectum to posterior. Other organs were reported to be normal. The patient underwent a laparotomy by a general gynecologic surgeon in which the mass was felt behind the vagina. Due to retroperitoneal location of the mass and lack of surgeon experience, the abdomen was closed without manipulation and the patient was referred to another center. She had another laparotomy about 4 months later revealing a simple ovarian cyst that led to cystectomy. In ovarian pathological assessment, a simple serous cyst was reported. So again they could not help the patient to eliminate her tumor. The patient did not seek further treatment until about 12 months later, when she came to our center due to continued pain and intercourse problem. On vaginal examination, a large mass was revealed posterior to the cervix, which caused the posterior wall of the vagina to bulge and the cervix to deviate anteriorly and below the pubic symphysis. The patient was thus planned for abdominal and pelvic MRI with and without contrast along with diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) imaging. In this assessment, it was reported a 120 × 120 × 105 mm pearl shape lobulated mass seemed to be originating from rectovaginal space, extraperitoneal, and extended upward and left in presacral space and deviating rectum to right side and uterus and vagina anteriorly. No invasion to adjacent structures was revealed, but the adhesion to rectal wall, vaginal posterior wall, levator ani muscle was found with extention between internal and external sphincter (Fig. 1, Fig. 2). all findings could be aggressive angiomyxoma or other benign mesenchymal tumors. other organs are normal. In this regard, the diagnosis of aggressive angiomyxoma was made. Laboratory assessment found no abnormal findings (white blood cell count of 10,000/mm3, serum hemoglobin level of 12.5 g/dl, platelet count of 156,000/mm3, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) of 1.2 ng/mL, cancer antigen-125 (CA 125) of 9 u/mL, and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) of 14 u/mL. The patient underwent re-laparotomy. The surgery was done by the first author with more than 20 years of experience in gynecologic oncology surgery. The abdomen was opened with a midline incision. The uterus had completely changed position anteriorly and a mass was felt deep behind the uterus and vagina. Due to the lack of access to the mass and also because the patient did not want to maintain fertility, hysterectomy and salpingectomy were performed first however the ovaries were preserved according to the patient’s age. Then the retroperitoneal space opened that a large mass was found behind the vaginal wall, the rectum had changed position to the right and extended to the pre-sacral space and down to the anal sphincter with the adhesion to the levator ani muscles. A 10 cm mass was completely and evenly removed (Fig. 3). Due to its adhesion to the rectum, a temporary ileostomy was implanted for the patient and then a sample was sent for pathological assessment. The patient did not have any complications after the operation and was discharged in good general condition with serum hemoglobin level of 10.5 g/dl. About 6 weeks later, the patient’s ileostomy was removed and the patient did not have any complications. The pathological report’s aggressive angiomyxoma with clear margins (Fig. 4). To prevent recurrence, GnRH agonist was prescribed. At six-month follow-up, the patient's symptoms completely disappeared and no mass was seen on imaging.

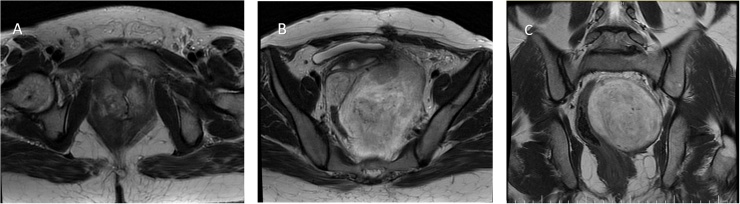

Fig. 1.

axial (A, B) and coronal (C)T2 shows a lesion originated from the perineum, breaks through the puborectal and levator ani muscles, extended into the left ischiorectal fossa and pushed to the right and anterior the rectum, uterus and bladder, without invading them.

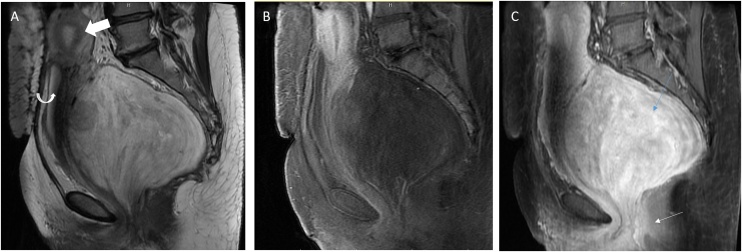

Fig. 2.

(A) Sagittal T2-weighted image of the pelvis, (B) sagittal T1-weighted fat saturated image and (C) Contrast-enhand sagittal T1-weighted fat saturated image showed tumor extending from the extraperineal (thin white arrow(C)) into the pelvis (thin blue arrow (C)). The mass demonstrates marked enhancement and has internal low-intensity “swirled” signal on all image sequences. Adjacent structures, including the urinary bladder (curved arrows) and uterus (thick arrow), are shifted to the anterior but are not invaded by the tumor.

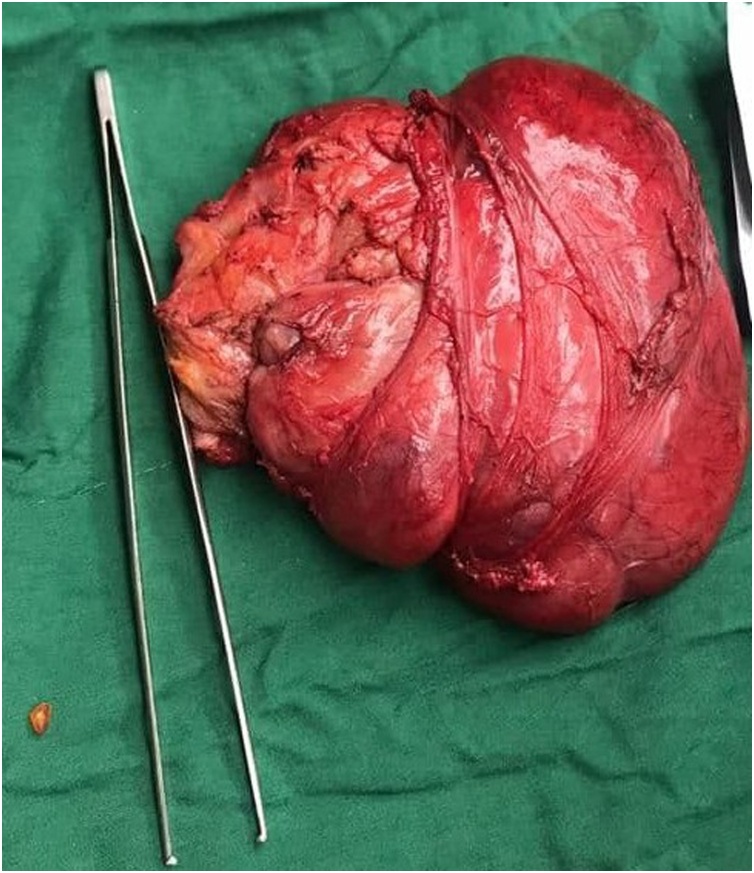

Fig. 3.

The feature of tumor resected surgically. The large size of tumor in comparison with large pick-ups with teeth is shown.

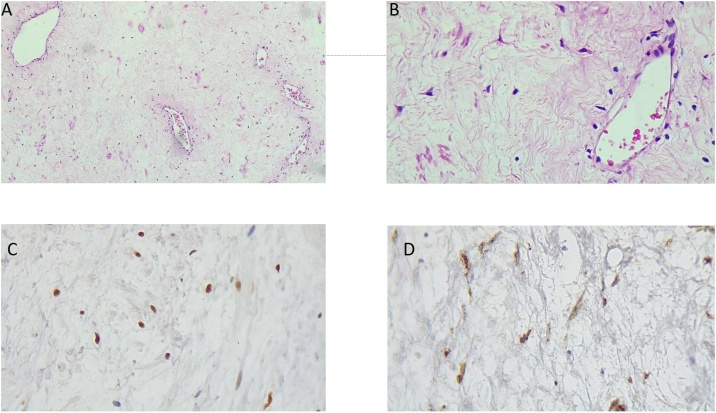

Fig. 4.

(A): x100 H & E staining feature (B): x400 H& E staining feature (C): IHC for estrogen receptors (D): IHC for SMA.

3. Discussion

Aggressive angiomyxoma is recognized as a benign mesenchymal neoplasm with local infiltrative behavior. Tumors are more common in women (more than 6 times more common in women than men) [5]. The presented age of tumor at initial presentation widely range 11–70 years with the peak of reproductive ages [5]. The primary size of mass considerably varies (ranged 1–60 cm), but its rapid growth is common even before it becomes symptomatic and can thus commonly displace adjacent viscera and even destruct the organs [6]. Because of its slow-growing behavior, it may remain asymptomatic for a long time until it is accidentally discovered during clinical evaluations or abdominopelvic imaging [7]. Although invasion of aggressive angiomyxoma is rarely reported, this event can occur to adjacent organs including bowel, bladder, and even bone. Due to aggressive behavior and invasion to adjacent organs, excisional resection of these tumors is difficult and is associated with high morbidity. Its main differential diagnoses include pelvic and vaginal cysts, vulvar masses or abscesses, the Bartholin duct cysts, perineal masses, and even hernias [8]. So the diagnosis of these tumors may be difficult, although MRI with DWI is helpful nowadays.

Due to its high recurrent behavior but no metastasis, its diagnostic differentiation from other tumors with a high chance of metastasis is very important, and in this regard, the use of diagnostic methods, especially pathological evaluation, is essential. In pathological assessment, aggressive angiomyxoma is manifested with bulky gelatinous mass with infiltrative margin and also visible small vessels [9]. In microscopic assessment, the lesions are paucicellular with minimal nuclear atypia and infrequent mitoses [9]. Potential myogenic differentiation has been also reported in such mass. The expression of vimentin, desmin, and muscle–specific actin has been also reported in stromal cells, but with negative reactivity for myoglobin, CD68, cytokeratin, S-100, or type-IV collagen [10]. In this regard, because of its overlapping with some other tumor lesion such as cellular angiofibroma or angiomyofibroblastoma, the pointed immunoreactivity may not be sensitively diagnostic [11]. The definitive therapeutic approach is surgical resection with pre-procedural imaging (particularly MRI) to determine the best surgical root to achieve complete margin-free excision [12]. Although it’s recurrence is common, we should have a plan to prevent it. Along with surgical planning, the use of hormonal manipulation especially for preventing its recurrence is of special interest. It has been found that prescribing GnRH agonist even without mass surgical resection can lead to reduce in tumor size as well as prevent its recurrence [13]. It should be noted that because of low mitotic activity of aggressive angiomyxoma tissue, the beneficial effects of chemotherapy or radiotherapy have remained doubtful.

Our described case initially complained of abdominal pain and problem in intercourse, as nonspecific symptoms that could not be improved by initial management. Thus, in further assessment by imaging followed by diagnostic laparotomy and histological assessment, the definitive diagnosis of aggressive angiomyxoma was made. Following ultimate diagnosis, the operation could lead to successful tumor resection, and prescribing GnRH agonist could prevent tumor recurrence with success. According to two retrospective studies by Kumar et al. and Haldar et al. on ten and seven patients with aggressive angiomixoma, surgical resection is the treatment of choice in aggressive angiomyxoma with a complete success rate, however, despite such success, about two-thirds of patients experienced postoperative recurrence rate that could be prevented by hormone-based therapy especially GnRH agonist [14,15]. Overall, slowing tumor extension leading to delayed tumor diagnosis, expression of different types of hormonal receptors, therapeutic ineffectiveness of noninvasive treatment approaches such as radiotherapy have remained as the major challenges for managing this tumor.

4. Conclusion

Aggressive angiomyxoma (AAM) is a rare and benign tumor with a locally invasive behavior, but not distant metastasis. As misdiagnosis is common imaging like MRI with DWI should be considered as a helpful diagnostic tool. The best treatment of AAM is surgical resection but because of the location and local invasion, it may be hard. So it’s better done by experienced surgeons in tertiary referral hospitals. Despite complete resection, the recurrence rate is high. then close follow-up and adjunct medical therapies are essential parts of treatment.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Sourcesof funding

Nothing to declare.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contribution

-

1.

S.AKH.: Main surgeon of the patient, Editing the final manuscript.

-

2.

S.N.: collecting data.

-

3.

B.B.: one of the patient surgeon.

-

4.

M.M.: reporting and interpretation of patient’s imaging.

-

5.

H.S.: pathologist, and preparing pathology figures.

-

6.

N.Z.: writing and editing the article, corresponding.

Registration of research studies

Not applicable.

Guarantor

Narges Zamani.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Chong C. Aggressive angiomyxoma. Nurse Pract. 2016;41(September (9)):1–4. doi: 10.1097/01.NPR.0000490398.27464.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Espiritusanto J., Carballido Rodriguez J., Linares Espinos E., Rengifo Abbad D., Van de Brule Rodriguez de Medina E., Osorio Cabello L., Areche Espiritusanto J. Aggressive pelvic angiomyxoma. Arch. Esp. Urol. 2014;67(April (3)):288–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu L., Wang L.H., Ren Y.B., Rao X.S., Yang S.M. Clinicopathological analysis of aggressive angiomyxoma of soft tissue in abdomino-pelvic cavity. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2018;50(December (6)):1098–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agha R.A., Franchi T., Sohrabi C., Mathew G., for the SCARE Group The SCARE 2020 guideline: updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2020;84:226–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan Y.M., Hon E., Ngai S.W., Ng T.Y., Wong L.C., Chan I.M. Aggressive angiomyxoma in females: is radical resection the only option? Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2000;79:216–220. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2000;79:432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amante S., Sousa R., Amaral R. Pelvic soft tissue aggressive angiomyxoma. J. Belg. Soc. Radiol. 2020;104(September (1)):55. doi: 10.5334/jbsr.2230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Korecka K.K., Hyla-Klekot L.E., Kudela G.P., Paleń P.A., Kajor M.W., Koszutski T.K. Aggressive angiomyxoma in an 11-year-old boy - diagnostic and therapeutic dilemmas: an unusual case report and review of the literature. Urology. 2020;144(October):205–207. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2020.05.028. Epub 2020 May 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zou R., Xu H., Shi Y., Wang J., Wang S., Zhu L. Retrospective analysis of clinicopathological features and prognosis for aggressive angiomyxoma of 27 cases in a tertiary center: a 14-year survey and related literature review. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020;302(July (1)):219–229. doi: 10.1007/s00404-020-05592-5. Epub 2020 May 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Surabhi V.R., Garg N., Frumovitz M., Bhosale P., Prasad S.R., Meis J.M. Aggressive angiomyxomas: a comprehensive imaging review with clinical and histopathologic correlation. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2014;202(June (6)):1171–1178. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.11668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fetsch J.F., Laskin W.B., Lefkowitz M., Kindblom L.G., Meis-Kindblom J.M. Aggressive angiomyxoma: a clinicopathologic study of 29 female patients. Cancer. 1996;78(July (1)):79–90. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960701)78:1<79::AID-CNCR13>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y.F., Qian H.L., Jin H.M. Local recurrent vaginal aggressive angiomyxoma misdiagnosed as cellular angiomyofibroblastoma: a case report. Exp. Ther. Med. 2016;11(May (5)):1893–1895. doi: 10.3892/etm.2016.3097. Epub 2016 Feb 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fucà G., Hindi N., Ray-Coquard I., Colia V., Dei Tos A.P., Martin-Broto J., Brahmi M., Collini P., Lorusso D., Raspagliesi F., Pantaleo M.A., Vincenzi B., Fumagalli E., Gronchi A., Casali P.G., Sanfilippo R. Treatment outcomes and sensitivity to hormone therapy of aggressive angiomyxoma: a multicenter, international, retrospective study. Oncologist. 2019;24(July (7)):e536–e541. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0338. Epub 2018 Dec 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pannier D., Cordoba A., Ryckewaert T., Robin Y.M., Penel N. Hormonal therapies in uterine sarcomas, aggressive angiomyxoma, and desmoid-type fibromatosis. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2019;143(November):62–66. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2019.08.007. Epub 2019 Aug 31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar N., Goyal A., Manchanda S., Sharma R., Kumar A., Bansal V.K. Aggressive pelvic angiomyxoma and its mimics: can imaging be the guiding light? Br. J. Radiol. 2020;93(July (1111)) doi: 10.1259/bjr.20200255. Epub 2020 May 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haldar K., Martinek I.E., Kehoe S. Aggressive angiomyxoma: a case series and literature review. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2010;36(April (4)):335–339. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2009.11.006. Epub 2009 Dec 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]