Abstract

Introduction:

Acute anterior uveitis (AAU), affecting up to 40% of patients with axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA), risks permanent visual deficits if not adequately treated. We report 2-year results from C-VIEW, the first study to prospectively investigate certolizumab pegol (CZP) on AAU in patients with active axSpA at high risk of recurrent AAU.

Patients and methods:

C-VIEW (NCT03020992) was a 104-week (96 weeks plus 8-week safety follow-up), open-label, multicenter study. Eligible patients had active axSpA, human leukocyte antigen-B27 (HLA-B27) positivity and a history of recurrent AAU (⩾2 AAU flares in total; ⩾1 in the year prior to baseline). Patients received CZP 400 mg at weeks 0, 2 and 4, then 200 mg every 2 weeks to week 96. The primary efficacy endpoint was the AAU flare event rate during 96 weeks’ CZP versus 2 years pre-baseline.

Results:

Of 115 enrolled patients, 89 initiated CZP (male: 63%; radiographic/non-radiographic axSpA: 85%/15%; mean disease duration: 9.1 years); 83 completed week 96. There was a significant 82% reduction in AAU flare event rate during CZP versus pre-baseline [rate ratio (95% confidence interval): 0.18 (0.12–0.28), p < 0.001]. One hundred percent and 59.6% of patients experienced ⩾1 and ⩾2 AAU flares pre-baseline, respectively, compared to 20.2% and 11.2% during treatment. Age, sex and axSpA population subgroup analyses were consistent with the primary analysis. There were substantial improvements in axSpA disease activity with no new safety signal identified.

Conclusion:

CZP treatment significantly reduced AAU flare event rate in patients with axSpA and a history of AAU, indicating CZP is a suitable treatment option for patients at risk of recurrent AAU.

Trial Registration ClinicalTrials.gov:

NCT03020992, URL: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03020992

Keywords: axial spondyloarthritis, extra-articular manifestations, TNF inhibitor, uveitis

Introduction

Spondyloarthritis (SpA) refers to a group of chronic inflammatory diseases, including axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA), that are characterised by involvement of the axial and peripheral skeleton.1 Although SpA is primarily a musculoskeletal condition, ocular involvement, particularly acute anterior uveitis (AAU), is considered to be an important clinical feature of the disease.2 AAU, which is a non-infectious, acute inflammation of the anterior uveal tract and adjacent structures, is the most common extra-musculoskeletal manifestation in axSpA.1,2 Reports from patients with radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (r-axSpA) suggest that as many as 40% of patients will experience at least one AAU flare during the course of their disease. A lower prevalence has been reported for patients with non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA) but data are limited.3–7

The clinical burden of AAU can be substantial, as it is commonly associated with photophobia, pain and blurred vision, and substantially affects patients’ quality of life.2,8 Complications including glaucoma, cataracts and iris atrophy may also arise as a result of cumulative damage from recurrent AAU, which may lead to permanent loss of visual acuity.2,9 Moreover, delayed or inadequate treatment, with poor control of the underlying inflammation, may result in permanent visual deficits.9 The prevalence of AAU flares in axSpA patients has been shown to increase with disease duration and is greater in human leukocyte antigen-B27 (HLA-B27) positive patients; patients with axSpA are reported to have a 2.6 to 4.2-fold greater risk of developing AAU if they are HLA-B27 positive.1,2,7,10 HLA-B27-related AAU has been associated with an earlier onset, an increased risk of relapse and more often, development of decreased visual acuity compared with HLA-B27 negative disease.11 Considering the potential consequences of AAU, it would be beneficial if treatment for patients with axSpA and AAU both targets axSpA symptoms and effectively reduces the risk of AAU flares, particularly in the high-risk patient populations described.1

While most AAU attacks typically resolve with first-line, topical corticosteroid treatment combined with mydriatics, some patients develop refractory or highly recurrent AAU, which may require further medical intervention.1,2 The onset of flares in highly recurrent AAU is unpredictable, with variable remission periods spanning from weeks to months, and effective preventive treatments are limited.12 Biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs), especially monoclonal antibodies against tumor necrosis factor (TNF), have been proved effective for the treatment of axSpA. Such treatment may also confer benefit for severe and unresponsive cases of AAU, as well as episodic and recurrent AAU. Several studies have evaluated the efficacy of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFis), including infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab and etanercept, on r-axSpA-related AAU, with findings reflected in the relevant axSpA treatment recommendations.1,2,13–21 Adalimumab is currently the only biological to have received US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for the treatment of uveitis in adults. However, approval is only indicated for intermediate uveitis, posterior uveitis and panuveitis, and does not extend to AAU.2,22 There remains a paucity of specific data for HLA-B27 positive patients with AAU, as well as data from well-controlled trials for the general axSpA population; to date, most studies have either been observational or limited to patients with r-axSpA.1,14,15,17,18

Certolizumab pegol (CZP) is a PEGylated Fc-free TNFi, indicated for the treatment of adult patients with active axSpA, and is the only FDA-approved TNFi for both r-axSpA and nr-axSpA.23,24 It has been shown to improve the signs and symptoms of axSpA as well as extra-musculoskeletal manifestations, including AAU, in patients across the full axSpA spectrum.24 Anterior uveitis data from the RAPID-axSpA and C-axSpAnd studies showed that the rate of AAU flares was lower for patients treated with CZP than placebo.25–27 The C-VIEW study aims to provide further robust evidence for the efficacy of CZP in preventing AAU flares and is the first clinical trial to prospectively assess the impact of CZP on AAU in an axSpA population at high risk of recurrent AAU. Results from a 48-week interim analysis of C-VIEW data have been published previously.28 Here, we report the final 2-year outcomes.

Patients and methods

Patients and study design

We report the final results from AS0007/C-VIEW (ClinicalTrials.gov number NCT03020992), a 104-week (96 weeks plus 8-week safety follow-up), open-label, single-arm, phase IV study that prospectively investigated the effect of CZP on the frequency of AAU flares in patients with both active axSpA (r-axSpA and nr-axSpA) and a recent history of recurrent AAU. This was achieved by comparing the historical AAU flare rate that occurred during the 2 years prior to the start of CZP treatment with the flare rate occurring during the 96-week CZP treatment period, adjusting for differences in the length of time of the pre-study and on-study periods.

Patients were recruited between 22 December 2016 and 13 December 2017 from 23 sites in five European countries (Czech Republic, Germany, The Netherlands, Poland and Spain). The study was approved by institutional review boards and independent ethics committees at participating sites and was conducted in accordance with local regulations and the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice requirements, based on the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent to participate.

For study entry, patients were required to have a diagnosis of axSpA, fulfilling Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) classification criteria29 with active disease [defined as a Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) score ⩾4 and spinal pain (BASDAI item 2) ⩾4]. Eligible patients were ⩾18 years of age and HLA-B27 positive, with a documented history of AAU diagnosed by an ophthalmologist and a history of ⩾2 AAU flares in total and ⩾1 AAU flare in the year prior to study entry. In addition, patients could be enrolled in C-VIEW providing they had not been exposed to >1 TNFi prior to baseline and were not primary non-responders (defined as no response within the first 12 weeks of TNFi treatment). Infliximab, adalimumab and golimumab exposure was not permitted in the 3 months prior to baseline and use of etanercept was not permitted in the 28 days prior to baseline. Change in dose regimen for conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs) and/or exposure to cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolic acid or apremilast in the 28 days prior to baseline were also not permitted; doses could only be reduced throughout the study in cases of intolerance.

During the treatment period, eligible patients received a loading dose of CZP 400 mg at weeks 0, 2 and 4, followed by subcutaneous CZP 200 mg every 2 weeks (Q2W) up to week 96 (final CZP dose administered at week 94). A safety follow-up visit was scheduled at week 104, 10 weeks after administration of the last CZP dose. Detailed study design and inclusion criteria for the C-VIEW study have been reported previously.28

Study endpoints

The primary endpoint was the frequency of AAU flares during 96 weeks’ CZP treatment, assessed by counting distinct episodes of AAU flares. Patients were requested to contact their ophthalmologist when they suspected an AAU flare at any time during the study. Flares on the same eye were counted as one flare if the time interval between two subsequent flares was <3 months (90 days) as recurrence of the first flare due to premature tapering of AAU treatment could not be excluded. AAU flares occurring on different eyes were considered separate episodes. Flares were confirmed by the ophthalmologist who recorded the treatment and duration of the flare. At each visit, AAU flares that had occurred since the last visit were evaluated. Details of pre-baseline flares were collected during screening and were based on ophthalmologist assessment. Further information on details recorded by treating ophthalmologists for AAU flares, both during the 2-year period prior to baseline and during the treatment period, have previously been reported.28

The following key secondary endpoints were also assessed at each study visit: Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS), BASDAI, ASAS 20%/40% and partial remission responses (ASAS20/40/PR), Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI), ASDAS thresholds of improvement [major improvement (MI): decrease of ⩾2.0 units from baseline; clinically important improvement (CII): decrease of ⩾1.1 units from baseline], ASDAS inactive disease (ID; ASDAS < 1.3), Patient’s Global Assessment of Disease Activity (PtGADA), Physician’s Global Assessment of Disease Activity (PhGADA), total spinal pain, Ankylosing Spondylitis Quality of Life (ASQoL), ASAS Health Index (ASAS HI) and fatigue (BASDAI Q1).

Adverse events were recorded according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities®, version 19.0.

Statistical analyses

Assuming an approximate 50% reduction in AAU flares during CZP treatment, a sample size of 86 patients would provide a statistical power of 80%.28

Efficacy and safety variables were analyzed for the safety set, which consists of all enrolled subjects who received at least one dose of CZP during the study. The primary efficacy analysis compared the AAU flare event rate in the 2 years prior to CZP treatment with the 96-week treatment period. AAU flare event rate was calculated based on the number of cases per patient and for the primary analysis is presented as the event rate per 96 weeks. AAU flare event rate per 104 weeks, including all flares post-baseline plus the 8-week safety follow-up, was also reported. Because the AAU event rate was based on counts of AAU flares, it was assumed that it would follow a Poisson distribution.30 As such, analysis of the primary variable was performed using Poisson regression, adjusted for possible within-patient correlation (between the retrospective and prospective AAU flare counts) and for the difference in duration of time of the pre and post-baseline periods, with period (pre and post-baseline) and axSpA disease duration as covariates. The p-value for the primary efficacy analysis (based on a two-sided significance level of alpha = 0.05), along with the rate ratio (CZP/historical) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were obtained from this model. AAU event rate, both pre- and post-baseline, is also reported per 100 patient-years (PY) of exposure.

Additional prespecified analyses of the primary endpoint were performed for patients in the full analysis set stratified by axSpA subpopulation (r-axSpA/nr-axSpA), age (</⩾45 years) and sex. Disease activity outcomes are also reported for patients who did and did not experience AAU flares during treatment.

For the sensitivity analysis, AAU flares were counted as reported by the investigator and were not combined if the time interval between two subsequent flares was <3 months (90 days).

Secondary efficacy variables pertaining to axSpA disease are reported as mean (standard deviation; SD) for continuous measures and n (%) for response rates. All patient-reported outcomes were assessed using a numerical rating scale (0–10). Observed data are presented; no adjustment was made to account for missing data.

All statistical analyses beyond the primary efficacy analysis are exploratory only. Any p-values or CIs produced in association with secondary or other analyses are considered non-confirmatory. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 or above.

Results

Patient disposition and baseline characteristics

A total of 115 patients were enrolled in the study. Of these, 89 initiated CZP treatment; 93.3% (n = 83/89) of patients completed the week 96 visit. Six patients discontinued from the study (four patients in the first year and two in the second year); five patients did so due to adverse events (two cases of prostate cancer, which were not related to CZP treatment and one case each of abnormal sensation in the eye, sarcoidosis and psoriasis, which were considered treatment related by the investigator) and one patient withdrew consent. At baseline, the mean age of the patient population was 46.5 years, and 63% (n = 56/89) were male. Additional demographics and baseline characteristics for all patients are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and patient characteristics.

| CZP 200 mg Q2W (N = 89) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 46.5 (11.2) |

| Male, n (%) | 56 (63) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 27.3 (5.1) |

| Racial group: Caucasian, n (%) | 87 (98) |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Radiographic axSpA | 76 (85) |

| Non-radiographic axSpA | 13 (15) |

| Time since axSpA diagnosis (years), mean (SD) | 9.1 (8.6) |

| Time since onset of axSpA symptomsa (years), mean (SD) | 16.1 (11.1) |

| HLA-B27 positive, n (%) | 89 (100) |

| Acute anterior uveitis history, n (%) | 89 (100) |

| Time since onset of first AAU flare (years), mean (SD) | 10.1 (9.2) |

| Patients with active flare at baseline, n (%) | 5 (6) |

| Psoriasis history, n (%) | 3 (3) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease history, n (%) | 0 |

| Prior medication exposure, n (%) | |

| TNFib | 5 (6) |

| NSAIDs | 85 (96) |

| Conventional DMARDs | 22 (25) |

| Concomitant medication use at baseline, n (%) | |

| TNFi | 0 |

| NSAIDs | 76 (85) |

| Conventional DMARDsc | 16 (18) |

| Systemic corticosteroidsd | 15 (17) |

| CRP, mg/L, mean (SD) | 13.8 (27.2) |

| CRP >ULN, n (%) | 30 (34) |

| ASDAS, mean (SD) | 3.5 (1.0) |

| BASDAI total score, mean (SD) | 6.5 (1.5) |

| Total spinal pain score, mean (SD) | 6.7 (2.0) |

| BASFI, mean (SD) | 5.1 (2.4) |

| Patient’s GADA, mean (SD) | 6.7 (2.2) |

| Physician’s GADA, mean (SD) | 5.9 (2.1) |

| Tender joint count ⩾1, n (%) | 59 (66) |

| Swollen joint count ⩾1, n (%) | 33 (37) |

Patients were enrolled from the Czech Republic (n = 35), Germany (n = 6), The Netherlands (n = 6), Poland (n = 38) and Spain (n = 4).

All patient-reported outcomes were assessed using a numerical rating scale (0–10), with higher numbers indicating poorer outcomes.

Symptom duration according to back pain, spinal pain or inflammatory pain. Disease duration is used where these preferred terms were not available from the patient’s medical history.

Etanercept in four patients and investigational drug (etanercept versus placebo) for the remaining patient.

Five patients received sulfasalazine, 11 received methotrexate and two received methotrexate sodium.

Six patients received methylprednisolone, four received prednisone acetate, two received prednisolone and one patient each received beclometasone dipropionate, budesonide and dexamethasone.

ASDAS, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score; axSpA, axial spondyloarthritis; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BASFI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index; BMI, body mass index; CRP, C-reactive protein; CZP, certolizumab pegol; DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; GADA, global assessment of disease activity; HLA-B27, human leukocyte antigen-B27; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; Q2W, every 2 weeks; SD, standard deviation; TNFi, tumor necrosis factor inhibitor; ULN, upper limit of normal.

Number and incidence of anterior uveitis flares

In the 2-year pre-treatment period, all patients experienced ⩾1 AAU flare and 59.6% experienced ⩾2 AAU flares. During 96 weeks of CZP treatment, the percentage of patients experiencing ⩾1 or ⩾2 AAU flares decreased to 20.2% and 11.2%, respectively (Figure 1A). The number of patients experiencing ⩾3 AAU flares decreased from 17 (19.1%) in the pre-treatment period to zero on-study. The mean (SD) number of AAU flares per patient was 1.9 (0.9) in the 2 years pre-baseline, compared with 0.3 (0.7) during CZP treatment (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

A. Percentage of patients experiencing 0, 1 or ⩾2 AAU flares. B. Mean number of AAU flares per patient. C. Poisson-adjusted AAU event rate per 96 weeks. Full analysis set (N = 89).

AAU, acute anterior uveitis; CZP, certolizumab pegol; Q2W, every 2 weeks.

Poisson regression analysis revealed an 82% reduction in the AAU flare event rate per 96 weeks, which included 96 week pre- and post-treatment periods (1.87 versus 0.34, p < 0.001; Figure 1C). The rate ratio (CZP/historical) was 0.18 (95% CI 0.12–0.28). The AAU flare event rate per 104 weeks, including post-baseline flares during the follow-up period and a 2-year pre-treatment period, also revealed an 82% reduction in flares (event per 104 weeks 0.37 versus 2.04). The AAU event rate per 100 PY decreased from 97.5 (95% CI 83.2–113.5) to 17.7 (95% CI 11.7–25.5) during treatment.

Similar reductions in the frequency of flares during CZP treatment were also observed in the sensitivity analysis, whereby AAU flares were counted as reported by the investigator, irrespective of the time interval between flares. In the 2 years pre-baseline, 100% and 64.0% of patients experienced ⩾1 and ⩾2 AAU flares, respectively, compared with 20.2% and 11.2% of patients during the treatment period. Consistent with the primary efficacy analysis, there was an 82% reduction in the AAU event rate per 96 weeks for investigator-reported flares [rate ratio (95% CI): 0.18 (0.11, 0.28), p < 0.001].

Post-hoc analyses of AAU flares for patients who completed the study to week 96 (n = 83) were also consistent with the primary analysis (Poisson-adjusted incidence: 1.93 pre-treatment versus 0.35 during treatment, p < 0.001). Further analyses revealed a similar mean (SD) number of AAU flares per subject between weeks 0–48 [0.2 (0.4)] and weeks 48–96 [0.1 (0.4)] of the study. The percentage of patients experiencing 0, 1 and 2 AAU flares in weeks 0–48 were 85.4% (n = 76/89), 12.4% (n = 11/89) and 2.2% (n = 2/89), compared to 88.8% (n = 79/89), 7.9% (n = 7/89) and 3.4% (n = 3/89), respectively, in weeks 48–96.

AAU flares by subgroups

Subgroup analyses investigated AAU flare event rates stratified by axSpA subpopulation, age and sex, and showed no significant differences. In patients with r-axSpA (n = 76), Poisson regression analysis showed a reduction in AAU flare event rate from 1.88 to 0.34 per 96 weeks [rate ratio: 0.18 (95% CI 0.11–0.29)], and in nr-axSpA (n = 13) the event rate was reduced from 1.82 to 0.33 per 96 weeks [rate ratio: 0.18 (95% CI 0.07–0.50)], respectively. For patients <45 years of age (n = 44), the event rate reduced from 1.80 to 0.30 per 96 weeks [rate ratio: 0.16 (95% CI 0.08–0.33)], compared to a reduction of 1.97 to 0.38 per 96 weeks [rate ratio: 0.20 (95% CI 0.11–0.34)] in patients ⩾45 years (n = 45). Male patients (n = 56) showed a reduction in AAU flare event rate from 1.89 to 0.28 per 96 weeks [rate ratio: 0.15 (95% CI 0.08–0.27)], compared to a reduction of 1.86 to 0.44 [rate ratio: 0.24 (95% CI 0.12–0.46)] in female patients (n = 33).

Duration of AAU flares

A heat map showing AAU flare duration for patients in the full analysis set (N = 89), both pre- and post-baseline, is shown in Supplemental Figure S1. As per inclusion criteria, all patients experienced ⩾1 AAU flare in the year prior to study entry. During the 2-year pre-baseline period, the mean (SD) duration of total days flaring per flare per patient was 91.9 (95.3) days. Eighteen of 89 patients experienced AAU flares during the 96-week treatment period. For these patients, the mean (SD) duration of total days flaring per flare per patient was 97.3 (66.7) days in the 2-year pre-baseline period, compared with 74.4 (55.3) days during 96 weeks of CZP (mean reduction of 22.9 days).

Disease activity

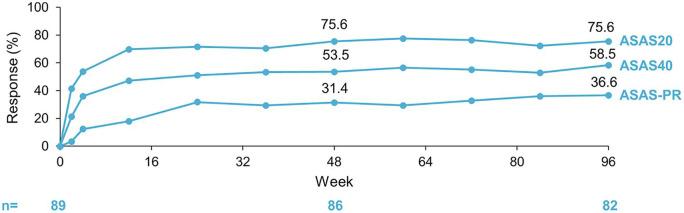

Over the 96-week treatment period, ASDAS and BASDAI improved substantially (Figure 2). In addition, between baseline and week 96, the mean (SD) ASDAS score decreased from 3.5 (1.0) to 1.9 (1.0) and the mean (SD) BASDAI score decreased from 6.5 (1.5) to 3.0 (2.1). After 96 weeks of CZP, 35.4% (n = 29/82) of patients achieved clinical remission as indicated by ASDAS-ID; 69.5% (n = 57/82) and 31.7% (n = 26/82) achieved ASDAS-CII and ASDAS-MI, respectively. Furthermore, by week 96, 75.6% (n = 62/82), 58.5% (n = 48/82) and 36.6% (n = 30/82) of patients had achieved ASAS20, ASAS40 and ASAS-PR responses, respectively (Figure 3). A subgroup analysis of the 18 patients who developed AAU flares during the study revealed that 66.7% achieved ASAS40 and 11.1% achieved ASDAS-MI at week 96 [compared with 56.3% and 37.5% of non-flarers at week 96 (n = 64)]. Additional secondary endpoints, including BASFI, PtGADA, PhGADA, total spinal pain, ASQoL, ASAS HI, and fatigue (according to BASDAI Q1), also showed improvements at the end of the treatment period (Table 2).

Figure 2.

A. Mean ASDAS and B. mean BASDAI to week 96. Safety set (N = 89). Observed data are shown.

ASDAS, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity index; SD, standard deviation.

Figure 3.

ASAS20, ASAS40 and ASAS partial remission response rates. Safety set (N = 89). Observed data are shown.

ASAS, Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society; PR, partial remission.

Table 2.

Additional disease activity outcomes following 96 weeks of CZP 200 mg Q2W.

| Disease activity measure | Week 0 (N = 89) | Week 96 (n = 82) |

|---|---|---|

| ASDAS, mean (SD) | 3.5 (1.0) | 1.9 (1.0) |

| ASDAS disease activity,a n (%) | ||

| Inactive disease | 0 | 29 (35.4) |

| Major improvement | N/A | 26 (31.7) |

| Clinically important improvement | N/A | 57 (69.5) |

| BASDAI, mean (SD) | 6.5 (1.5) | 3.0 (2.1) |

| BASFI, mean (SD) | 5.1 (2.4) | 2.8 (2.4) |

| Patient’s GADA, mean (SD) | 6.7 (2.2) | 2.7 (2.3) |

| Physician’s GADA, mean (SD) | 5.9 (2.1) | 1.6 (2.0) |

| Total spinal pain, mean (SD) | 6.7 (2.0) | 2.7 (2.1) |

| ASQoL, mean (SD) | 10.6 (5.1) | 4.4 (4.6) |

| ASAS HI, mean (SD) | 9.3 (3.7) | 4.6 (3.9) |

Observed data are shown.

All patient-reported outcomes were assessed using a numerical rating scale (0–10), with higher numbers indicating poorer outcomes.

ASDAS inactive disease: ASDAS <1.3; ASDAS major improvement: decrease of ⩾2.0 units from baseline; ASDAS clinically important improvement: decrease of ⩾1.1 units from baseline.

ASAS HI, Assessment of Axial Spondyloarthritis international Society Health Index; ASDAS, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score; ASQoL, ankylosing spondylitis quality of life; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BASFI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index; CZP, certolizumab pegol; GADA, global assessment of disease activity; Q2W, every 2 weeks; SD, standard deviation.

Safety

Overall, 72/89 (80.9%) patients in the safety set experienced an adverse event during the study; excluding cases of uveitis, iridocyclitis and iritis, 65/89 patients (73.0%) experienced an adverse event. Of these, 10 patients (11.2%) experienced at least one serious adverse event, with 14 serious adverse events reported in total (Table 3). These included one case each of cholelithiasis, incarcerated hernia, anal polyp, tenosynovitis, haemangioma, sarcoidosis, breast cancer and pregnancy (recorded as serious due to elective termination), and two cases each of vestibular disorder, pneumonia and prostate cancer. Of these, the cases of breast cancer and sarcoidosis were considered to be treatment related by the investigator.

Table 3.

Safety outcomes.

| MedDRA 19.0 term, n (%)b | CZP 200 mg Q2W (N = 89) |

|---|---|

| Any adverse event (AE) | 65 (73.0) (281) |

| Infections and infestations | 44 (49.4) (99) |

| Upper respiratory tract infections | 33 (37.1) (59) |

| Serious AEsa | 10 (11.2) (14) |

| Discontinuation of CZP due to AEs | 5 (5.6) (5) |

| Drug-related AEs | 19 (21.3) (48) |

| Severe AEs | 5 (5.6) (6) |

| Deaths | 0 |

AEs are reported using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities® (MedDRA) version 19.0 and exclude events of uveitis, iridocyclitis and iritis.

Serious AEs (recorded as such by the investigator) were: one case each of cholelithiasis, incarcerated hernia, anal polyp, pneumonia haemophilus, pneumonia, tenosynovitis, haemangioma, sarcoidosis, breast cancer and pregnancy (recorded as serious due to elective termination), and two cases each of vestibular disorder and prostate cancer.

Number of occurrences.

AE, adverse event; CZP, certolizumab pegol; Q2W, every 2 weeks.

In addition, two events of AAU, which occurred in a single patient, were recorded as treatment-related serious adverse events by the local investigator. As local treatment guidelines required uveitis to be treated in a hospital rather than an outpatient clinic, this patient was hospitalized for further diagnostic work-up; hence, these were recorded as a serious adverse events. There were no deaths or serious cardiovascular events during the study.

Discussion

C-VIEW is the first study to prospectively investigate the impact of the TNFi CZP on AAU as a primary outcome in patients with active axSpA and a high risk of recurrent AAU. In this study, during 96 weeks of CZP treatment, a significant reduction of 82% in both the AAU flare event rate per patient, and the overall AAU flare rate per 100 PY was found, compared with the 2 years prior to treatment. Results were further corroborated by the analysis of the 104-week interval, which included the 8-week safety follow-up, as well as by the sensitivity analyses for investigator-reported AAU flares.

C-VIEW includes axSpA patients with a recent history of AAU, considered to be at a high risk for flares. However, it is notable that the AAU incidence rate observed during CZP treatment was comparable with patients from RAPID-axSpA, who had a history of AAU but had not necessarily experienced a recent flare. Post-hoc analyses from the RAPID-axSpA trial reported an AAU flare rate of 17.1 per 100 PY (95% CI 3.5–50.1) after 24 weeks of CZP treatment compared with 17.7 per 100 PY (95% CI 11.7–25.5) after 96 weeks in C-VIEW.26 The AAU flare rate achieved with CZP during C-VIEW was also comparable with prospective reports of other monoclonal antibody TNFis in patients with r-axSpA; however, differences in study design limit direct comparisons.18,19,29

As a secondary aim, this study also evaluated the effect of CZP on AAU flare event rate in patients stratified by age, sex and axSpA subpopulation. Subgroup analyses for age and axSpA subtype were consistent with the primary efficacy analysis; both r-axSpA and nr-axSpA subgroups achieved an 82% reduction in AAU flare event rate per 96 weeks, with no substantial differences observed for patients stratified by age (< or ⩾45 years). The efficacy of TNFis has been observed to be lower in females with axSpA compared with males for subjective outcome measures,31 but little has been reported on sex differences in the treatment of uveitis. In this study, the male and female subgroups achieved reductions in AAU flare event rate of 85% and 76%, respectively. However, whether this difference was true or occurred by chance is not known as the study was not powered to draw definite conclusions for these subgroups.

Relevant improvements in patients’ axSpA disease activity, according to ASDAS, BASDAI and ASAS responses, were also demonstrated in the C-VIEW study, which were in line with previous studies of CZP.24,25,27 Moreover, CZP was well tolerated during the 96-week treatment period; no new safety signal was identified compared to previous reports28 and only five of 89 subjects who initiated CZP discontinued the study due to adverse events, which was consistent with previous reports of CZP in axSpA.24,25 The incidence and type of adverse events were also consistent with the known safety profile of CZP.23 Two events of AAU that occurred in a single patient were deemed as treatment-related serious adverse events. However, this was due to local practice, which necessitated hospital admission for uveitis treatment in contrast to practice in other centers.

Effective preventive treatments for highly recurrent AAU are limited.12 Some csDMARDs, including sulfasalazine and methotrexate, may have potential in the management of relapsing AAU, although larger randomized controlled trials are needed to confirm findings as available evidence is currently limited to observational reports.1,2 In addition, sulfasalazine and methotrexate are not indicated for the treatment of axial symptoms in axSpA and are only recommended for cases of prominent peripheral arthritis.20,21 Some csDMARDs, such as methotrexate, are also teratogenic and therefore not without risk for treating women with axSpA who are of reproductive age.32

The 2016 ASAS–European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) guidelines recommend biologicals for patients with axSpA who fail to respond to conventional treatments and highlight the initiation of TNFi therapy over other biologicals due to more extensive experience and clinical data.21 American College of Rheumatology (ACR)–Spondylitis Association of America (SAA)–Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network (SPARTAN) guidelines published in 2019 also emphasize the importance of treating anterior uveitis associated with axSpA and conditionally recommend treatment with TNFi monoclonal antibodies.20 Adalimumab was the first biological to receive FDA approval as a treatment for uveitis, encompassing non-infectious intermediate, posterior and panuveitis, based on the results of interventional studies.22,33 However, data from interventional studies in AAU are limited to a few observational studies; studies investigating the impact of TNFis, including adalimumab and golimumab, on AAU in axSpA have generally been performed as observational, open-label studies with historical controls.1,14,16–19 Previous placebo-controlled studies investigating CZP in axSpA have been performed (C-axSpAnd and RAPID-axSpA) but these evaluated AAU as an additional outcome only.25,26

The open-label study design without a concurrent control group is a limitation of C-VIEW. However, as the study enrolled patients who were at a high risk of developing recurrent AAU and who had high axSpA disease activity at baseline, assigning them to placebo was considered unethical, especially given the 2-year observation period. Moreover, there are no regulatory agency-approved preventive treatments for anterior uveitis associated with axSpA to serve as a suitable comparator arm. Within-patient comparisons were conducted by comparing the number of flares pre- and post-baseline, which could result in a regression to the mean phenomenon. However, evaluating AAU flares over a period of 2 years limited such an effect as a similar incidence of AAU flares was observed between weeks 0–48 and weeks 48–96 of the study.

As C-VIEW only enrolled patients with axSpA and HLA-B27 positivity, our findings are not generalizable to a patient population with HLA-B27 negative disease. However, HLA-B27 is a key genetic marker for axSpA, identified in approximately 90% of patients,2,12 and has been associated with a substantially increased risk (2.6 to 4.2-fold) of developing of AAU.10 Therefore, it can be expected that this study is representative of the majority of patients with both axSpA and AAU. A HLA-B27 positive population was also selected for this study as these patients generally have more frequent and severe episodes of AAU.11 Furthermore, as 98% of patients in C-VIEW were Caucasian, the extent that CZP would reduce the frequency of AAU flares in other ethnic groups cannot be determined. However, this patient demographic is consistent with other studies of AAU in axSpA and may be attributed to the increased prevalence of the HLA-B27 allele in this population.18,19,34

Despite these caveats, the C-VIEW study has a number of strengths. It is the first study to investigate the reduction of AAU flares in the broad axSpA population, encompassing both r-axSpA and nr-axSpA, in patients with HLA-B27 positive disease.1,18,25 Furthermore, the study duration of 96 weeks is longer than other studies in axSpA-related anterior uveitis.18,19,25,26,29 Prospective studies comparing historical AAU flare rates for adalimumab and golimumab in patients with r-axSpA were carried out for a maximum of 52 weeks only.18,19,29 Additional strengths of this study include adherence to a strict protocol and complete assessment of uveitis flares during treatment. While the comparison made to pre-baseline flares is not as rigorous as a concurrent placebo arm, the requirement for an ophthalmologist-documented history of flares within 2 years of the baseline visit strengthened the approach. Furthermore, during the treatment period, patients received the recommended dose of CZP, which is indicated for the treatment of axSpA and has been shown to be safe and effective for reducing the primary symptoms of axSpA.23

To conclude, final C-VIEW results demonstrate a significant reduction in AAU flare incidence and improvement in axSpA symptoms over a 2-year treatment period with CZP. These data indicate that CZP is a suitable treatment option for patients across the full axSpA spectrum with recurrent AAU.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-tab-10.1177_1759720X211003803 for Reduction of anterior uveitis flares in patients with axial spondyloarthritis on certolizumab pegol treatment: final 2-year results from the multicenter phase IV C-VIEW study by Irene E. van der Horst-Bruinsma, Rianne E. van Bentum, Frank D. Verbraak, Atul Deodhar, Thomas Rath, Bengt Hoepken, Oscar Irvin-Sellers, Karen Thomas, Lars Bauer and Martin Rudwaleit in Therapeutic Advances in Musculoskeletal Disease

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients, the investigators and their teams who took part in this study. The authors also acknowledge Theresa Rosario-Jansen, UCB Pharma, USA, for critical revision and Simone E. Auteri, UCB Pharma, Belgium for critical revision and publication coordination, as well as Abbie Rogers and Jessica Patel, from Costello Medical, UK, for medical writing and editorial assistance based on the authors’ input and direction. This study was funded by UCB Pharma.

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions: IvdHB, FDV, TR, BH, OIS, KT, LB, and MR have substantially contributed to study conception and design; IvdHB, RvB, FDV, AD, TR, BH, OIS, KT, LB, and MR have substantially contributed to analysis and interpretation of the data; IvdHB, RvB, FDV, AD, TR, BH, OIS, KT, LB, and MR were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version of the article to be published.

Conflict of interest statement: Irene E. van der Horst-Bruinsma: Honoraria/consulting fees/research grants from AbbVie, BMS, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB Pharma; Rianne E. van Bentum: none; Frank D. Verbraak: Honoraria/consulting fees/research grants from Bayer, Novartis, IDxDR, UCB Pharma; Atul Deodhar: Honoraria/consulting fees/research grants from AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS, Eli Lilly, GSK, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB Pharma; Thomas Rath: Honoraria/consulting fees from AbbVie, BMS, Chugai, Eli Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, UCB Pharma; Bengt Hoepken, Oscar Irvin-Sellers, Lars Bauer: Employees of UCB Pharma; Karen Thomas: Former contractor with UCB Pharma; Martin Rudwaleit: Honoraria/consulting fees from AbbVie, BMS, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, UCB Pharma.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was sponsored by UCB Pharma. This article was based on the original study AS0007/C-VIEW (NCT03020992) sponsored by UCB Pharma. Support for third-party writing assistance for this article, provided by Abbie Rogers and Jessica Patel, Costello Medical, UK, was funded by UCB Pharma in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines (http://www.ismpp.org/gpp3).

Ethics approval: The study was approved by institutional review boards and independent ethics committees at participating sites and was conducted in accordance with local regulations and the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice requirements, based on the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent to participate.

Prior publication: The 2-year primary results from the C-VIEW study have previously been presented as a poster at the ACR Virtual Convergence 2020 (5–9 November).

Data sharing statement: Underlying data from this manuscript may be requested by qualified researchers 6 months after product approval in the USA and/or Europe, or global development is discontinued, and 18 months after trial completion. Investigators may request access to anonymized individual patient-level data and redacted trial documents which may include analysis-ready datasets, study protocol, annotated case report form, statistical analysis plan, dataset specifications, and clinical study report. Prior to use of the data, proposals need to be approved by an independent review panel at www.Vivli.org and a signed data sharing agreement will need to be executed. All documents are available in English only, for a pre-specified time, typically 12 months, on a password protected portal.

ORCID iD: Irene E. van der Horst-Bruinsma  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8086-9915

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8086-9915

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Contributor Information

Irene E. van der Horst-Bruinsma, Department of Rheumatology, Amsterdam University Medical Center, Location VU Medical Center, De Boelelaan 1117, Amsterdam, 1081 HV, The Netherlands.

Rianne E. van Bentum, Department of Rheumatology, Amsterdam University Medical Centers, Location VU Medical Centre, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Frank D. Verbraak, Department of Ophthalmology, Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Atul Deodhar, Division of Arthritis and Rheumatic Diseases, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR, USA.

Thomas Rath, Department of Opthalmology, St Franziskus-Hospital, Münster, Germany.

Bengt Hoepken, UCB Pharma, Monheim am Rhein, Germany.

Oscar Irvin-Sellers, UCB Pharma, Slough, UK.

Karen Thomas, UCB Pharma, Monheim am Rhein, Germany.

Lars Bauer, UCB Pharma, Monheim am Rhein, Germany.

Martin Rudwaleit, Clinic for Internal Medicine and Rheumatology, Klinikum Bielefeld and Department of Gastroenterology, Infectiology and Rheumatology, Charité Berlin, Germany.

References

- 1. Biggioggero M, Crotti C, Becciolini A, et al. The management of acute anterior uveitis complicating spondyloarthritis: present and future. Biomed Res Int 2018; 2018: 9460187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bacchiega ABS, Balbi GGM, Ochtrop MLG, et al. Ocular involvement in patients with spondyloarthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2017; 56: 2060–2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rosenbaum JT, Smith JR. Anti-TNF therapy for eye involvement in spondyloarthropathy. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2002; 20: S143–S145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Frantz C, Portier A, Etcheto A, et al. Acute anterior uveitis in spondyloarthritis: a monocentric study of 301 patients. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2019; 37: 26–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. De Winter JJ, Van Mens LJ, Van Der Heijde D, et al. Prevalence of peripheral and extra-articular disease in ankylosing spondylitis versus non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: a meta-analysis. Arthritis Res Ther 2016; 18: 196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rudwaleit M, Haibel H, Baraliakos X, et al. The early disease stage in axial spondylarthritis: results from the German spondyloarthritis inception cohort. Arthritis Rheum 2009; 60: 717–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zeboulon N, Dougados M, Gossec L. Prevalence and characteristics of uveitis in the spondyloarthropathies: a systematic literature review. Ann Rheum Dis 2008; 67: 955–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. O’Rourke M, Haroon M, Alfarasy S, et al. The effect of anterior uveitis and previously undiagnosed spondyloarthritis: results from the DUET cohort. Rheumatology 2017; 44: 1347–1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gutteridge IF, Hall AJ. Acute anterior uveitis in primary care. Clin Exp Optom 2007; 90: 70–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lim CSE, Sengupta R, Gaffney K. The clinical utility of human leucocyte antigen B27 in axial spondyloarthritis. Rheumatology 2017; 57: 959–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zheng MQ, Wang YQ, Lu XY, et al. Clinical analysis of 240 patients with HLA-B27 associated acute anterior uveitis. Eye Sci 2012; 27: 169–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rademacher J, Poddubnyy D, Pleyer U. Uveitis in spondyloarthritis. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 2020; 12: 1759720X20951733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Calvo-Río V, Blanco R, Santos-Gómez M, et al. Golimumab in refractory uveitis related to spondyloarthritis. Multicenter study of 15 patients. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2016; 46: 95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lie E, Lindström U, Zverkova-Sandström T, et al. Tumour necrosis factor inhibitor treatment and occurrence of anterior uveitis in ankylosing spondylitis: results from the Swedish biologics register. Ann Rheum Dis 2017; 76: 1515–1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Braun J, Baraliakos X, Listing J, et al. Decreased incidence of anterior uveitis in patients with ankylosing spondylitis treated with the anti-tumor necrosis factor agents infliximab and etanercept. Arthritis Rheum 2005; 52: 2447–2451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Guignard S, Gossec L, Salliot C, et al. Efficacy of tumour necrosis factor blockers in reducing uveitis flares in patients with spondylarthropathy: a retrospective study. Ann Rheum Dis 2006; 65: 1631–1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rudwaleit M, Rødevand E, Holck P, et al. Adalimumab effectively reduces the rate of anterior uveitis flares in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis: results of a prospective open-label study. Ann Rheum Dis 2009; 68: 696–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Van Bentum RE, Heslinga SC, Nurmohamed MT, et al. Reduced occurrence rate of acute anterior uveitis in ankylosing spondylitis treated with golimumab – the GO-EASY study. Rheumatology 2019; 46: 153–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Van Denderen JC, Visman IM, Nurmohamed MT, et al. Adalimumab significantly reduces the recurrence rate of anterior uveitis in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology 2014; 41: 1843–1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ward MM, Deodhar A, Gensler LS, et al. 2019 update of the American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network recommendations for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis and nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2019; 71: 1285–1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Van Der Heijde D, Ramiro S, Landewé R, et al. 2016 Update of the ASAS–EULAR management recommendations for axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017; 76: 978–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Food and Drug Adninistration. HUMIRA (adalimumab). Product information: Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL, USA. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2008/125057s0110lbl.Pdf (2008; accessed 28 October 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 23. Food and Drug Adninistration. CIMZIA (certolizumab pegol). Product information: UCB, Inc., Smyrna, GA, USA. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/125160s237lbl.Pdf (2019; accessed 30 October 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 24. Landewé R, Braun J, Deodhar A, et al. Efficacy of certolizumab pegol on signs and symptoms of axial spondyloarthritis including ankylosing spondylitis: 24-week results of a double-blind randomised placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014; 73: 39–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Deodhar A, Gensler LS, Kay J, et al. A fifty-two-week, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of certolizumab pegol in nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019; 71: 1101–1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rudwaleit M, Rosenbaum JT, Landewé R, et al. Observed incidence of uveitis following certolizumab pegol treatment in patients with axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2016; 68: 838–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Van Der Heijde D, Dougados M, Landewé R, et al. Sustained efficacy, safety and patient-reported outcomes of certolizumab pegol in axial spondyloarthritis: 4-year outcomes from RAPID-axSpA. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2017; 56: 1498–1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Van Der Horst-Bruinsma I, Van Bentum R, Verbraak FD, et al. The impact of certolizumab pegol treatment on the incidence of anterior uveitis flares in patients with axial spondyloarthritis: 48-week interim results from C-VIEW. RMD Open 2020; 6: e001161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rudwaleit M, Van Der Heijde D, Landewé R, et al. The development of assessment of spondyloarthritis international society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part II): validation and final selection. Ann Rheum Dis 2009; 68: 777–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Agresti A. Generalized linear models. In: Agrest A. (ed) An introduction to categorical data analysis. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wright GC, Kaine J, Deodhar A. Understanding differences between men and women with axial spondyloarthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2020; 50: 687–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Götestam Skorpen C, Hoeltzenbein M, Tincani A, et al. The EULAR points to consider for use of antirheumatic drugs before pregnancy, and during pregnancy and lactation. Ann Rheum Dis 2016; 75: 795–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bessette AP, Sharma S. Adalimumab for noninfectious uveitis. Ophthalmol Retina 2017; 1: 179–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Reveille JD, Hirsch R, Dillon CF, et al. The prevalence of HLA–B27 in the US: data from the US national health and nutrition examination survey, 2009. Arthritis Rheum 2012; 64: 1407–1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-tab-10.1177_1759720X211003803 for Reduction of anterior uveitis flares in patients with axial spondyloarthritis on certolizumab pegol treatment: final 2-year results from the multicenter phase IV C-VIEW study by Irene E. van der Horst-Bruinsma, Rianne E. van Bentum, Frank D. Verbraak, Atul Deodhar, Thomas Rath, Bengt Hoepken, Oscar Irvin-Sellers, Karen Thomas, Lars Bauer and Martin Rudwaleit in Therapeutic Advances in Musculoskeletal Disease