Abstract

Objective

To assess the association of dyslipidaemia with osteoporosis in postmenopausal women.

Methods

Data from 160 postmenopausal women with newly diagnosed osteoporosis (osteoporosis group) and 156 healthy controls (control group) were retrospectively reviewed from 2016 to 2020. The primary outcomes were laboratory values assessed by a multivariate binary logistic regression model.

Results

Factors that greatly increased the risk of being in the osteoporosis group included high low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels. The osteoporosis group had lower HDL and higher LDL levels than the control group. A multivariate binary logistic regression model showed that lower HDL and higher LDL levels were the only variables that were significantly associated with osteoporosis (odds ratio 1.86, 95% confidence interval: 3.66–4.25 and odds ratio 1.47, 95% confidence interval: 1.25–2.74, respectively).

Conclusion

Low HDL and high LDL levels may be associated with the occurrence of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women.

Keywords: Dyslipidaemia, osteoporosis, diabetes, low-density lipoprotein, high-density lipoprotein, bone mineral density, cholesterol

Introduction

Increasing laboratory evidence suggests that dyslipidaemia contributes to the risk of osteoporosis by upregulating osteoclast gene expression, which initiates a cycle of osteolysis that results in low bone mineral density (BMD).1–3 Osteoporosis is considered to be a result of an osteoblast synthesis disorder and abnormally active osteoclasts;3 however, there is no robust evidence to confirm this hypothesis.4 Limited studies5,6 have shown that diabetes in elderly patients tends to be a risk factor for osteoporosis. Additionally, elderly patients with dyslipidaemia and diabetes still suffer from osteoporosis, despite having normal blood glucose levels for more than 2 years while taking hypoglycaemic drugs,7–9 suggesting an association between dyslipidaemia and osteoporosis.

Whether dyslipidaemia and osteoporosis are positively correlated is controversial.10,11 Oestrogen is regarded as a major regulator of osteocyte homeostasis, and its paucity due to cessation of menstruation for at least 1 year is one factor associated with low BMD or osteoporosis.12,13 In this study, we investigated the relationship between dyslipidaemia and osteoporosis in postmenopausal women.

Materials and methods

Study population

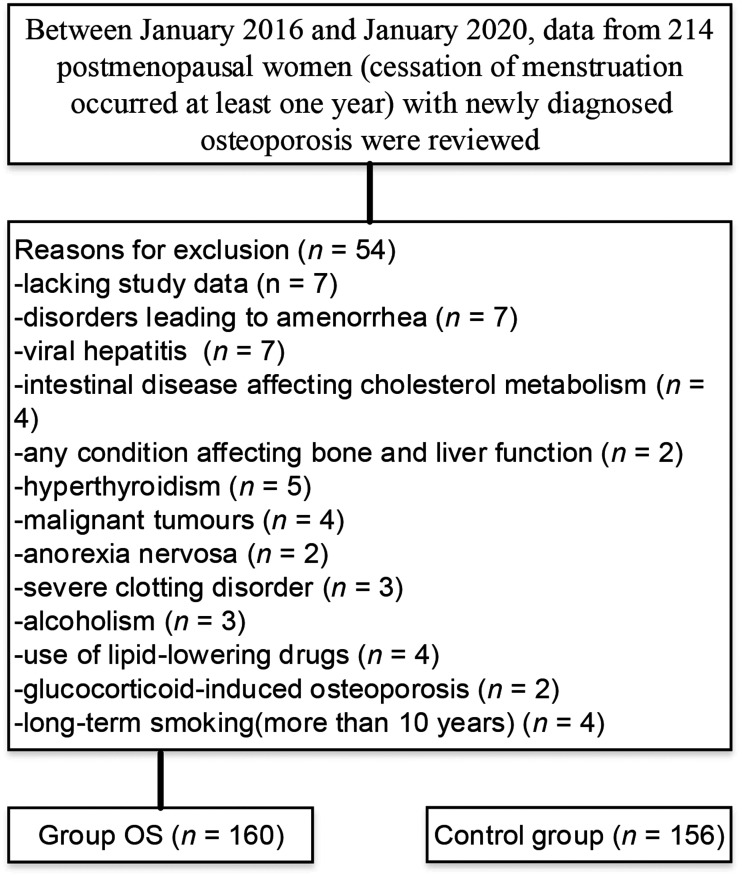

The study was approved by the institutional ethics review board of The Affiliated Hospital of Hebei University, Baoding (28 February 2020, IRB-20-193) and we obtained the patients’ written consent for treatment. We have de-identified all patients’ details. This retrospective study followed the relevant Equator network guideline (https://www.equator-network.org/). Between January 2016 and January 2020, data from 214 consecutive postmenopausal women (cessation of menstruation occurred at least 1 year previously) with newly diagnosed osteoporosis were reviewed retrospectively. Measurement of BMD and the sites of selected bones were based on previous reports.2,4 The diagnosis of osteoporosis was in accordance with a previous description.2 Classification of dyslipidaemia was consistent with the guidelines of the 2004 Update of the National Cholesterol Education Program14 (triglyceride [TG] levels ≥8.3 mmol/L, high-density lipoprotein [HDL] levels ≤2.2 mmol/L, and low-density lipoprotein [LDL] levels ≥8.9 mmol/L). Eligibility was restricted to all postmenopausal women. Only individuals meeting the criteria for newly diagnosed osteoporosis were included in the osteoporosis group. The main exclusion criteria were as follows: lack of study data, disorders leading to amenorrhoea, viral hepatitis, intestinal diseases affecting cholesterol metabolism (e.g., ulcerative colitis), any condition affecting bone and liver function (e.g., dysostosis and hepatocirrhosis), hyperthyroidism, malignant tumours, anorexia nervosa, severe clotting disorder (e.g., haemophilia), alcoholism, use of lipid-lowering drugs (e.g., atorvastatin), glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis, and long-term smoking (>10 years). Postmenopausal women without osteoporosis (controls) were identified from the physical examination centre of our institution. The primary outcomes were laboratory data, including blood levels of total cholesterol (TC), LDL, HDL, TGs, apolipoprotein A1 (Apo-A1), apolipoprotein B (Apo-B), and apolipoprotein E4 (ApoE4), and serum leptin and adiponectin levels. The blood sample collection procedure was consistent with that described previously.15

Statistical analysis

Nonparametric comparisons were performed for TG, HDL, TC, leptin, and adiponectin levels. Normality analysis was also performed. Categorical variables were compared with the chi-square test, and continuous variables were compared with the Student’s t-test (for normally distributed variables) and the Mann–Whitney U test (for non-normally distributed variables). A multivariate binary logistic regression model was used to assess which variables were superior for predicting outcomes. Because TC consists of TGs, LDL, and HDL, TC failed to be regarded as a risk factor. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). A two-sided p value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

A total of 160 elderly patients with newly diagnosed osteoporosis were included in the final analysis (osteoporosis group) (Figure 1). One hundred fifty-six individuals were included in the control group. The median age was 66.42 years (61–71 years) in the osteoporosis group and 66.88 years (61–72 years) in the control group (p = 0.067) The osteoporosis and control groups were similar regarding age, education, smoking, major medical diseases (e.g., nephrotic syndrome and arrhythmia), and major comorbidities (e.g., chronic obstructive lung disease and bronchiectasis) (Table 1). Levels of TC, LDL, and TGs were significantly higher in the osteoporosis group than in the control group (all p < 0.001). HDL levels were significantly lower in the osteoporosis group than in the control group (p < 0.001). The percentage of ApoE4 carriers was significantly lower in the osteoporosis group than in the control group, and the ApoE genotype was significantly different between the groups (both p < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing selection of a cohort of postmenopausal women with newly diagnosed osteoporosis and reasons for exclusion.

OS, osteoporosis.

Table 1.

Patients’ demographics and outcomes.

| Factor | Osteoporosis (n = 160) | Control (n = 156) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 66.42 ± 5.31 | 66.88 ± 5.65 | 0.067 |

| Education, years | 14.26 ± 9.82 | 14.53 ± 8.87 | 0.103 |

| Smoking | 7.34 ± 6.55 | 7.38 ± 5.79 | 0.322 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.01 ± 8.55 | 24.12 ± 7.36 | 0.271 |

| Leptin, ng/mL | 12.05 ± 9.73 | 12.16 ± 8.73 | 0.149 |

| Adiponectin, μg/mL | 16.45 ± 8.53 | 8.79 ± 7.82 | <0.001 |

| TC, mmol/L | 4.74 ± 0.82 | 4.11 ± 0.57 | <0.001 |

| HDL, mmol/L | 2.12 ± 0.36 | 3.87 ± 0.43 | <0.001 |

| LDL, mmol/L | 12.67 ± 0.86 | 7.51 ± 0.49 | <0.001 |

| TGs, mmol/L | 10.32 ± 0.75 | 8.53 ± 0.88 | <0.001 |

| Apo-A1, mg/mL | 1.00 ± 0.18 | 1.02 ± 0.18 | 0.182 |

| Apo-B, mg/mL | 0.57 ± 0.12 | 0.58 ± 0.14 | 0.112 |

| ApoE4 carrier, % | 60.2 | 39.4 | <0.001 |

| ApoE genotype, % | <0.001 | ||

| E2/2 | 3.6 | 4.2 | |

| E2/3 | 7.4 | 13.8 | |

| E2/4 | 2.5 | 6.5 | |

| E3/3 | 44.6 | 40.4 | |

| E3/4 | 38.2 | 32.2 | |

| E4/4 | 3.7 | 2.9 |

Data are mean ± standard deviation or %.

OS, osteoporosis; BMI, body mass index; TC, total cholesterol; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; TGs, triglycerides; Apo-A1, apolipoprotein A1; Apo-B, apolipoprotein B; ApoE4, apolipoprotein E4.

Table 2 shows the prediction of outcomes, which were analysed using a multivariate binary logistic regression model. Age was not involved because of a lack of difference in baseline age between the groups, although age is considered an independent predictive factor for osteoporosis. Lower HDL and higher LDL levels were associated with an increased risk of osteoporosis (odds ratio 1.86, 95% CI: 3.66–4.25, p < 0.001 and odds ratio 1.47, 95% CI: 1.25–2.74, p < 0.001, respectively) (TC was not regarded as a risk factor). Other variables were not associated with osteoporosis in the current analysis.

Table 2.

Multivariate binary logistic analysis of factors associated with osteoporosis in a cohort of postmenopausal women with newly diagnosed osteoporosis.

| Factors | β | SE | OR | 95% CI | χ2 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI | 1.105 | 0.216 | 1.44 | 0.23–2.40 | 6.31 | 0.129 |

| Leptin | 1.563 | 0.241 | 1.34 | 0.54–1.58 | 10.25 | 0.139 |

| Adiponectin | 1.103 | 0.342 | 1.52 | 0.87–3.49 | 7.07 | 0.435 |

| HDL | 1.87 | 0.107 | 1.86 | 3.66–425 | 3.14 | <0.001 |

| LDL | 1.53 | 0.226 | 1.47 | 1.25–2.74 | 3.76 | <0.001 |

| TGs | 1.231 | 0.435 | 1.41 | 0.83–2.45 | 11.08 | 0.362 |

| Apo-A1 | 2.218 | 4.302 | 2.11 | 0.63–4.71 | 6.06 | 0.135 |

| Apo-B | 1.402 | 2.135 | 1.25 | 0.27–3.93 | 12.33 | 0.176 |

| ApoE4 carrier | 1.613 | 4.386 | 1.13 | 0.45–2.15 | 4.79 | 0.143 |

| ApoE genotype | 2.041 | 3.293 | 2.12 | 0.28–3.10 | 3.82 | 0.186 |

SE, standard error; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; TGs, triglycerides; Apo-A1, apolipoprotein A1; Apo-B, apolipoprotein B; ApoE4, apolipoprotein E4.

Discussion

This retrospective review provides evidence that high LDL and low HDL levels may be associated with the occurrence of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. To the best of our knowledge, the present analysis is the largest study on the association of dyslipidaemia with osteoporosis in postmenopausal women.

Low HDL levels appear to indicate a high risk of osteoporosis, while high LDL levels appear to be a risk factor of osteoporosis. Postmenopausal women frequently have high serum lipid levels, including TC, LDL, Apo-A1, Apo-B, and ApoE4. In the present study, a multivariate binary logistic regression model showed that low HDL and high LDL levels were strong predictors of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women with cessation of menstruation for at least 1 year. Consistent with prior reports,11,16 other variables (e.g., TC, TGs, Apo-A1, Apo-B, and ApoE4) did not appear to be predictors of osteoporosis. Sage et al.17 showed that hyperlipidaemia inhibited proliferation of osteoblasts in mice. Accumulation of oxidised lipids in microvessels promotes the release of inflammatory factors, which in turn triggers changes in the microenvironment of the bone and ultimately leads to osteogenic disorders. Osteoporosis is associated with BMD, and BMD is associated with serum lipid profiles.18 Therefore, there appears to be an association between osteoporosis and dyslipidaemia.

Limited studies15,16,19 have assessed the effect of dyslipidaemia on osteoporosis and have shown that hydroxy-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitors substantially reduce the incidence of osteoporosis. To date, there have been few previous studies13,16 regarding dyslipidaemia associated with osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Alay et al.16 performed a case–control study involving 452 postmenopausal women and showed that hyperlipidaemia may be associated with osteoporosis. Whether serum lipid profiles are related to osteoporosis has received a great deal of attention.3 Cabrera et al.15 performed a pilot study involving 96 menopausal women aged 55 to 70 years and identified associations between lipid metabolism and osteoporosis. Based on similar scenarios, numerous reports4,5 have shown that serum lipid profiles are involved in initiating the occurrence of osteoporosis and that the onset of osteoporosis is related to the duration and extent of dyslipidaemia.

Female patients who experience cessation of menstruation for 1 year have low BMD.13 Dyslipidaemia is associated with pathological circumstances involving low BMD and bone loss, where signalling pathways tend to be disturbed or suppressed.9 The stability of osteoblasts versus serum lipids involves signalling pathways.1 Initiation of any factor or blocking of signalling pathways triggers disturbance of the balance, which ultimately leads to low BMD or osteoporosis.20 Dyslipidaemia plays a major role in this balance.21 This is mainly attributed to the fact that dyslipidaemia can not only directly trigger imbalance in this chain, but can also promote massive release of cytokines through the immune response, ultimately disrupting this balance.22 Osteoclasts and osteoblasts are the leading regulators of osteocyte homeostasis.10 Graham et al.23 highlighted an important role of the immune system, principally by means of activation-induced T lymphocyte production.

There are several limitations to this study. The retrospective nature of the current study and the adopted inclusion criteria reduced the ability to draw reliable conclusions. Additionally, the sample collection time was not constant, which may have had an effect on the results. Additionally, potential comorbidities were not completely considered in the cohorts included in the present analysis. Individuals who tend to have a high-fat and polysaccharide diet were not considered, which might have restricted our evidence level and eventually resulted in deviations. Our results are not able to be generalized because the current population was limited to postmenopausal women. The final limitation that cannot be overlooked is that, although general principles were obeyed, laboratory measurements may have been constrained by potential human factors.

In conclusion, our study shows that low HDL and high LDL levels may be associated with the occurrence of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. This finding implies that dyslipidaemia is substantially related to osteoporosis in female patients without intervention of oestrogen, which might be a baseline confounding variable. Large-sample control studies are necessary to further clarify this relationship.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding: This research received a grant from Hebei Province 2019 Medical Science Research Project Plan (Grant No. 20190934).

ORCID iDs: Xiaozhe Zhou https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7257-0550

Weiguang Yu https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6190-8336

References

- 1.Matsubara T, Ikeda F, Hata K, et al. Cbp Recruitment of Csk into Lipid Rafts Is Critical to c-Src Kinase Activity and Bone Resorption in Osteoclasts. J Bone Miner Res 2010; 25: 1068–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ongphiphadhanakul B, Chanprasertyothin S, Chailurkit L, et al. Differential associations of residual estradiol levels with bone mineral density and serum lipids in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Maturitas 2004; 48: 193–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ozgocmen S, Kaya H, Fadillioglu E, et al. Role of antioxidant systems, lipid peroxidation, and nitric oxide in postmenopausal osteoporosis. Mol Cell Biochem 2007; 295: 45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parhami F, Garfinkel A, Demer LL. Role of lipids in osteoporosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2000; 20: 2346–2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mori H, Okada Y, Kishikawa H, et al. Effects of raloxifene on lipid and bone metabolism in postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes. J Bone Miner Metab 2013; 31: 89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inzerillo AM, Epstein S. Osteoporosis and diabetes mellitus. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2004; 5: 261–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Z, Zhao GH, Zhang YK, et al . Research on the correlation of diabetes mellitus complicated with osteoporosis with lipid metabolism, adipokines and inflammatory factors and its regression analysis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2017; 21: 3900–3905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papandreou P, Agakidis C, Scouroliakou M, et al. Early Postnatal Changes of Bone Turnover Biomarkers in Very Low-Birth-Weight Neonates-The Effect of Two Parenteral Lipid Emulsions with Different Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Content: A Randomized Double-Blind Study. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2020; 44: 361–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma M, Wang CR, Ao Y, et al. HOXC10 promotes proliferation and attenuates lipid accumulation of sheep bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Mol Cell Probes 2020; 49: 101491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee KG, Lee GB, Yang JS, et al. Perturbations of Lipids and Oxidized Phospholipids in Lipoproteins of Patients with Postmenopausal Osteoporosis Evaluated by Asymmetrical Flow Field-Flow Fractionation and Nanoflow UHPLC-ESI-MS/MS. Antioxidants 2020; 9: 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Attane C, Esteve D, Chaoui K, et al. Human Bone Marrow Comprises Adipocytes with Specific Lipid Metabolism. Cell Rep 2020; 30: 949–958.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li S, Guo HB, Liu YS, et al. Relationships of serum lipid profiles and bone mineral density in postmenopausal Chinese women. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2015; 82: 53–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saoji R, Desai M, Das RS, et al. Estrogen receptor alpha and beta gene polymorphism in relation to bone mineral density and lipid profile in Northeast Indian women. Gene 2019; 710: 202–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CNB, et al. Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. Circulation 2004; 110: 227–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cabrera D, Kruger M, Wolber FM, et al. Association of Plasma Lipids and Polar Metabolites with Low Bone Mineral Density in Singaporean-Chinese Menopausal Women: A Pilot Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018; 15: 1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsu YH, Venners SA, Terwedow HA, et al. Relation of body composition, fat mass, and serum lipids to osteoporotic fractures and bone mineral density in Chinese men and women. Am J Clin Nutr 2006; 83: 146–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sage AP, Lu JX, Atti E, et al. Hyperlipidemia Induces Resistance to PTH Bone Anabolism in Mice via Oxidized Lipids. J Bone Miner Res 2011; 26: 1197–1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cho S, Jung I, Choi H, et al . Association of bone mineral density and lipid profiles in Korean women. J Bone Miner Res 2006; 21: S268. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cui RT, Zhou I, Li ZH, et al. Assessment risk of osteoporosis in Chinese people: relationship among body mass index, serum lipid profiles, blood glucose, and bone mineral density. Clin Interv Aging 2016; 11: 887–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu XF, Zhang YM, Lin H. The related variate analysis of blood lipid and bone mineral density in hypertension and/or coronary atherosclerotic heart disease. Bone 2008; 43: S119–S120. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Panahi N, Soltani A, Ghasem-Zadeh A, et al. Associations between the lipid profile and the lumbar spine bone mineral density and trabecular bone score in elderly Iranian individuals participating in the Bushehr Elderly Health Program: a population-based study. Arch Osteoporos 2019; 14: 52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Komatsu T, Park H, Sugiyama A, et al. Relationships between lipid metabolism and bone mineral density in community-dwelling elderly. Calcif Tissue Int 2008; 82: S195–S196. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graham LS, Parhami F, Tintut Y, et al. Oxidized lipids enhance RANKL production by T lymphocytes: Implications for lipid-induced bone loss. Clin Immunol 2009; 133: 265–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]