Abstract

Financial toxicity is a broad term to describe the economic consequences and subjective burden resulting from a cancer diagnosis and treatment. Across oncology, there is growing recognition of the problem and increasing calls for strategies to identify and support those most at risk since it is likely associated with poorer disease outcomes. Men with localized prostate cancer face treatment choices including active surveillance, prostatectomy, or radiotherapy. There has been scarce acknowledgement that potential patient out-of-pocket cost may influence decision making. More broadly, the risk of financial toxicity for men with localized prostate cancer remains poorly studied. In this review, we introduce the concept in the context of non-metastatic prostate cancer and propose a multidimensional framework for considering a patient’s risk of financial toxicity. We identify some early themes including that total cost patterns are likely different by treatment modality; surgery may produce greater short-term impact, but radiation may have higher long-term risk. Specific patient income levels or out-of-pocket cost thresholds predicting risk of financial toxicity will be difficult to identify. Finally, we speculate that compared to other malignancies, prostate cancer may have lower overall risk of financial toxicity, but that persistent post-treatment urinary, bowel or sexual side effects likely increase patient risk of financial toxicity.

Keywords: financial toxicity, distress, cost, prostate cancer, hardship

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the most common non-cutaneous adult male malignancy; in the United States 164,690 new cases were estimated in 2018.1 Nearly 80% of men will be diagnosed with localized disease. For these men, prognosis and recommended treatment paradigm is dictated by several factors including pre-treatment PSA level, extent of prostatic/extraprostatic involvement, and histological Gleason score. Men with prostate cancer often have the choice of numerous treatment options with similar oncologic outcomes but different toxicity profiles. The broad categories of options include radical prostatectomy, definitive radiotherapy (external beam radiotherapy or brachytherapy) with or without androgen deprivation therapy or active surveillance for appropriately selected candidates.

The factors influencing a patient’s treatment decision have been reviewed in detail.2–5 Overall, a physician’s specific recommendation remains the most influential driver. Patient perceptions of better cure rates and the avoidance of certain perceived side effects (e.g., urinary or sexual complications) are also valued. Men may be influenced strongly by familial pressure to choose a particular modality and men who prefer prostatectomy tend to value physical removal of the cancer. Interestingly, there is scarce mention of a patient’s potential financial responsibility as a core motivator. This is paradoxical given oncologists’ growing recognition of “financial toxicity” – a comprehensive term for patient harm due to the direct and indirect costs of cancer treatment.6

The concept of financial toxicity arose from concerns that rising costs of antineoplastic agents coupled with insurers’ increased cost-sharing with patients may produce negative outcomes akin to traditional treatment-associated “toxicities” like nausea or pain.6 This has blossomed into broad recognition that oncologists must confront the inconvenient truth that treating cancer may come at the cost of severe economic stress. In 2009, ASCO produced a consensus statement affirming that physician-patient discussions regarding costs are a critical component of high-value oncologic care.7

It is worth acknowledging that there have been numerous “cost” and “cost effectiveness” studies in prostate cancer. For example, a recent systematic review summarized the costs and cost effectiveness of several contemporary technological advancements in prostate cancer treatment (e.g., robot-assisted prostatectomy, intensity modulated radiotherapy and proton beam radiotherapy).8 These studies typically consider a treatment’s “cost” from the perspective of what is charged to an insurer or national payor, often weighed against estimated, quality-adjusted improvements in life expectancy as a result of that treatment. These types of studies are most valuable to, and utilized most often by, policymakers. For example, the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Healthcare and Excellence (NICE) relies on high quality technology assessment studies to determine which interventions will be covered by the national healthcare system. But, unless patients are completely uninsured, they are very rarely responsible for the full cost of their treatment. Thus, it is challenging to interpret these studies at a per-patient level. The financial toxicity we will discuss in this Review reflects economic stress at the patient level and not necessarily at the institutional or system level. In other words, an expensive intervention from a payor’s perspective may or may not cause financial toxicity depending on several patient-specific factors.

Overall, financial toxicity is felt to be rising due to numerous factors like more expensive cancer therapies, an aging population nearing retirement and in the US, a changing insurance landscape, which increasingly shifts cost responsibility to patients.9 A recent study investigating the large longitudinal Health and Retirement Study has estimated the risk to be substantial; across 9.5 million people with newly diagnosed malignancies between 2000-2012, at 2 years post diagnosis, 42% had depleted their entire life’s assets.10

One of the challenges of studying financial toxicity is the breadth of factors which can influence a patient’s propensity to feel economic hardship. A practical consideration when reviewing the literature is that many words (e.g., financial or cost burden, strain, hardship, distress or stress) can be used to define cancer’s multidimensional economic impact on a patient. Further adding to the complexity is that researchers have, to date, measured financial toxicity in different ways including a) monetary measurements (e.g., out-of-pocket costs sometimes as a share of personal income) b) prevalence rates of objective responses to financial strain (e.g., declaration of bankruptcy, increases in debt levels, reduction in leisure spending) or c) subjective perceptions of financial burden and possible impact on health-related quality of life.11

Oncologists’ heightened awareness of the issue is likely due to growing recognition that financial difficulties can translate to poorer physical health states. Financial toxicity may be a risk factor for several negative oncologic outcomes including worsened symptoms,12 heightened emotional and psychological distress,13,14 decreased quality of life15,16 and even greater mortality risk.17 The causal link between financial strain with worse outcomes are poorly studied, though several hypotheses have been presented. Practically, patients experiencing financial hardship are less likely to adhere to prescribed treatments and follow-up, which could result in higher rates of cancer relapse and death.18–20 This is particularly true for oral cancer medications. Interestingly, pre-clinical models also suggest that psychological stress can promote tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis through stress hormone and possibly immune mediated effects.21–24 Further research, however, is needed to better understand these relationships.

Patients are also growing increasingly concerned about cancer’s financial impact and want to discuss it with their healthcare providers.25 As these discussions still remain non-standardized, many feel the current level of physician engagement is inadequate.26

With respect to prostate cancer, we hypothesize that there are several forces which have the potential to produce significant financial toxicity. First, changing practice patterns and modern modalities like robotic surgery27 and proton therapy28 are driving up costs from a societal perspective.8 It remains unclear how these costs are being shifted to patients, though given insurance trends, we suspect that individual responsibilities may be rising. Recent approvals of expensive novel oral hormonal agents like abiraterone, enzalutamide and apalutamide as well as possible shifting of these medications into the paradigm for high risk localized disease may contribute as well.29 Second, the high worldwide prevalence of prostate cancer means that many men of varying socioeconomic strata are at risk. Third, a unique aspect of prostate cancer is that most men are cured of their disease and may thus carry over a decade of ongoing, associated medical costs. As many men are diagnosed while fully employed, there is also the possibility of workplace disruptions and prolonged opportunity costs.

Given the likelihood of continued prominence of this issue, the overarching goal of this Review is to summarize the current knowledge base on the risks of financial toxicity relating to patients with localized prostate cancer. To accomplish this, we will first propose a framework of several factors which appear to contribute generally to a cancer patient’s risk of developing financial toxicity. This will guide discussion of several emerging strategies to measure financial toxicity to help inform future prostate cancer focused research efforts. We will then utilize this framework to synthesize existent literature for localized prostate cancer, highlighting deficiencies when appropriate. While our default focus is on non-metastatic prostate cancer, we will occasionally refer to studies of other cancer histologies or advanced stage disease to highlight important concepts.

A framework for evaluating risk of cancer-associated financial toxicity

It is challenging for providers to prognosticate a patient’s risk for financial toxicity since it is inherently subjective and highly individualized. Studies across cancer types have identified several broad risk factors for financial strain including female gender, younger age, low baseline income, adjuvant therapies and more recent diagnosis11 but several of these are of limited utility given the epidemiology and treatment paradigm of prostate cancer.

Ramsey et al. linked SEER data with bankruptcy records and found that after propensity score matching, cancer patients who declared bankruptcy had a significantly greater adjusted mortality ratio of 1.79 (95% CI, 1.64 to 1.96).17 Interestingly, mortality differed by histology and prostate cancer was one of the strongest predictors of bankruptcy-associated risk. For men with localized or regional prostate cancer who declared bankruptcy within a year of diagnosis, the adjusted mortality ratio was 1.98 (95% CI 1.25 to 3.15, p=0.004). These findings underscore the importance of identifying prostate cancer patients with financial strain, as there might be opportunities for the healthcare team to assist patients in need and potentially modify their mortality risk.

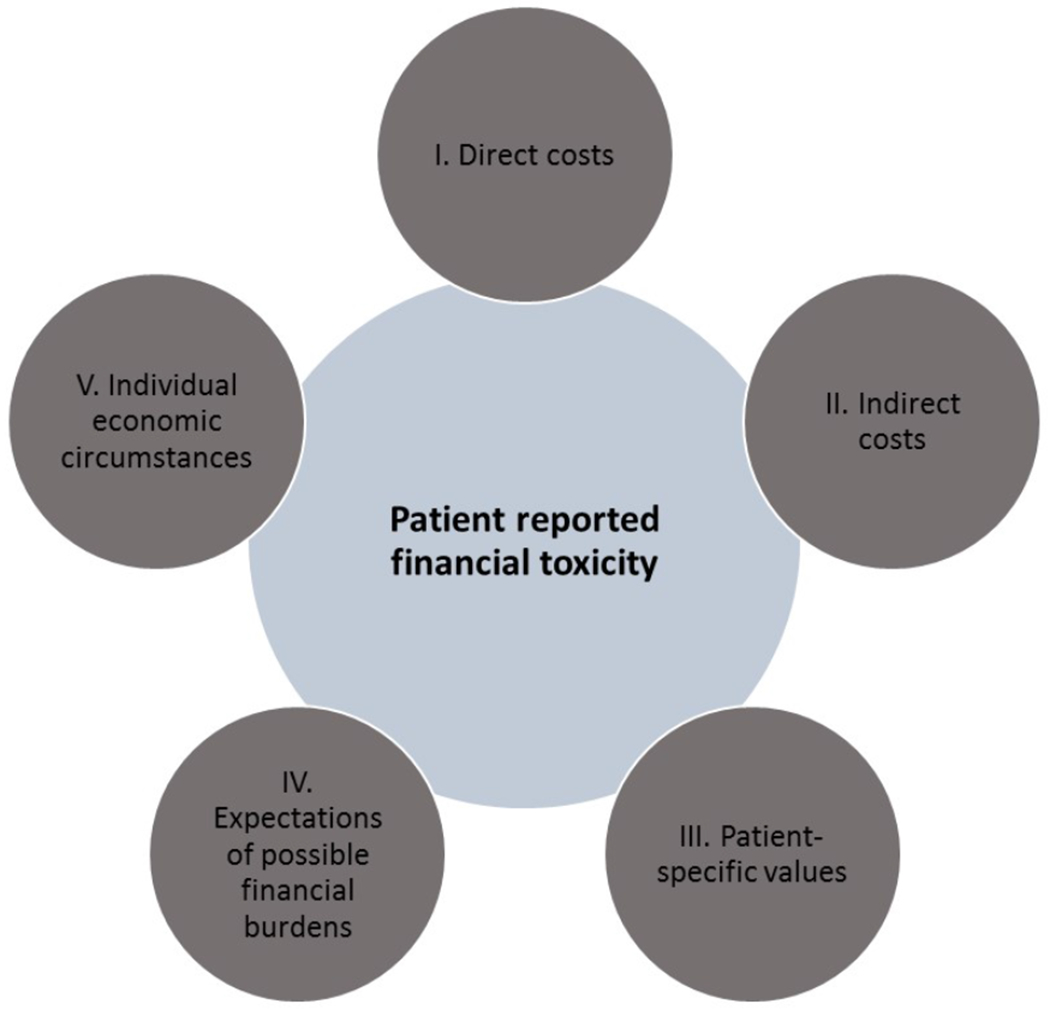

When a patient reports financial toxicity, this is an expression of their perceived overall impact of numerous complex factors which we propose as a Financial Toxicity Framework (Figure 1). Specific components of the Framework include:

FIGURE 1.

A proposed Financial Toxicity Framework for assessing a patient-level cancer related economic burden

I. Direct costs – the out-of-pocket (OOP) responsibility that a man faces due to prostate cancer, including insurance copayments, coinsurance and deductibles for medical visits, diagnostics, treatments, supportive care medications and follow-up. While most of these costs (particularly short term after treatment) are medically-derived, there are numerous non-medical costs as well including the costs of travel, parking, additional family care expenses, etc. Direct medical costs are themselves a function of the billed costs of required treatments, medications or services net what the patient’s insurance will pay. For healthcare systems with private insurance, this net sum is based on the patient’s primary insurance structure and degree of member cost-sharing and availability of supplemental insurance. For patients whose insurance plans have annual deductibles (which are increasingly common in the US), a patient’s medical expenses previously accrued (whether or not for prostate cancer) that calendar year will also factor in the required out-of-pocket burden.

II. Indirect costs – these reflect the opportunity costs of prostate cancer such as lost income due to a patient and/or spouse’s inability to work or decrease in productivity. Any lost wages from premature mortality may also be considered.30

III. Patient-specific values – the most difficult contributors to generalize are a patient’s personal preferences and perceptions which influence how they react to medical-related expenses. For some, continuation of treatment and/or maximization of curative potential is paramount even if associated with significant financial burden. For example, a survey of 300 insured, solid tumor (non-prostate) patients revealed that nearly half were willing to declare personal bankruptcy to receive care.31 For others, treatment preferences are guided by different priorities.4 Incongruity between a patient’s values and their selected treatment increases the chance of negative impressions of treatment related cost.

IV. Expectations of possible financial burdens – Anticipatory guidance on the possibility of significant medical costs may lessen the psychological impact. Effective communication between patients and physicians or other members of the care team (e.g., financial counselors) is an important component of setting expectations. Patients may be reticent to discuss cost concerns with their oncologist, particularly in time constrained visits. While the prevalence of patient-physician cost conversations around prostate cancer treatments is unknown, a survey of physicians caring for localized breast cancer patients suggests they may be infrequent – 51% of medical oncologists, 16% of surgeons and 43% of radiation oncologists report that their office “often” or “always” discusses financial burden with patients.26 A study by Chino et al. which included 300 patients with several non-prostate histologies, roughly a fifth of whom had localized disease, found that even after adjusting for financial burden as a share of income, unexpected costs are associated with lower willingness to pay.32 Patients are increasingly requesting more robust cost discussions during upfront treatment decision making.26,33,34

V. Individual economic circumstances – a patient’s baseline wealth, preexistent debts and economic reserve are undoubtedly key drivers of possible eventual toxicity. For example, $1,000 in incremental medical cost could be catastrophic to certain patients but insignificant to others. We will not address this topic in depth, but we encourage providers to consider the possibility of financial distress broadly since prostate cancer patients who feel subjectively burdened by cost may be socioeconomically heterogeneous.35 Studies in other cancers have demonstrated that insured patients remain at risk for financial strain18 and there remains a risk of underinsurance (defined as spending more than 10% of income on healthcare costs).32

One important lesson is there is significant heterogeneity in how researchers study these factors. Financial toxicity can be evaluated in both top down and bottom up approaches. A bottom up approach considers and weighs some, or all, of the five aforementioned factors to evaluate predisposition to financial toxicity (Figure 2A). A top down approach considers, instead, the final synthesis – does a patient report subjective distress or are there subjective or objective indicators it may be present (Figure 2B)? Many studies we reviewed have hybrid designs with components of both analytic techniques.

FIGURE 2.

Two different strategies for assessing financial toxicity. A) “Bottom up” approach to studying financial toxicity, considering individual patient-specific drivers and B) “Top down” approach to studying financial toxicity, considering overall patient reported distress

Strategies to assess financial toxicity

Given the complexity of what can contribute to financial toxicity, and how it can be studied, it is unsurprising that there are numerous potential outcome metrics or patient tools to help researchers assess a patient’s risk. Figure 3 is not exhaustive and offers examples but there has been considerable nuance in how these potential outcomes have been interpreted.11 A study’s “optimal” outcome depends on the specific research goal. For example, efforts aimed to better understand direct costs may audit patients’ cancer-associated payments over a given period.

FIGURE 3.

Overview of potential instruments and outcomes which have been utilized to study financial toxicity

Studies utilizing more top down approaches may instead choose to quantify objective implications of financial strain (e.g., analyzing patients’ declarations of bankruptcy) or screen patients holistically for subjective financial stress. A welcome addition has thus been the development of objective, patient-reported financial toxicity screening instruments.36,37 The COmprehensive Score for financial Toxicity, or COST score is an assessment of patient financial strain relying on 11 questions each with a 5-point Likert scale. COST is gaining traction as a preferred screening tool for financial toxicity research and has been proposed as a standardized instrument for future research efforts.11 COST was validated in advanced stage patients on systemic therapies38,39 making its applicability to localized prostate cancer unclear; to our knowledge, its performance has not been specifically studied in localized prostate cancer but anticipate this is forthcoming. Another utilized tool is the InCharge Financial Distress/Financial Well-Being Scale (IFDFW).37

To date, screening tools like COST have been principally utilized for research purposes, but we predict a trend to incorporate these data into clinical practice. Prostate cancer specialists already have strong experience collecting and tracking patient-reported quality of life metrics (e.g., urinary, bowel or sexual function) so inclusion of an additional tool should minimally impact clinical flow. It is premature to predict how this information will influence clinical practice or treatment recommendations.

In the upcoming sections, we will explore the framework using the specific lens of localized prostate cancer. Each domain in the framework also serves as a possible area for clinicians to provide anticipatory guidance or intervention.

Applying the Financial Toxicity Framework to patients with localized prostate cancer

Direct costs

American prostate cancer patients have multiple treatment options with widely different cost potential

Annual US nationwide prostate cancer expenditures are rising, and projected to range between $15-20 billion by 2020.40 Listed prices for medical services typically reflect costs billed to payers or directly to uninsured patients and rates of uninsured patients are projected to rise after repeal of the individual insurance mandate.41 These prices are typically inflated compared to true resource-driven economic costs42 or the amounts which are ultimately reimbursed which are usually negotiated downward as part of contracting processes between hospitals and payers.

The average listed prices (i.e., for an uninsured patient) of a radical prostatectomy procedure varies widely across the nation with mean hospital fees of $34,720 (standard deviation of $20,335 and min-max range of $10,000-$135,000).43 Estimates for physician and anesthetic fees were less robust but averaged over $8,000 (min-max range $4,028—18,720).

For patients who choose radiotherapy (RT), the two main categories include external beam RT or brachytherapy. Within external beam RT there are several main options including a traditional treatment course over approximately 9 weeks or moderately hypofractionated RT delivered over approximately 4-5 weeks. Additionally, ultra-hypofractionated RT regimens like stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT), which are completed in 5 or fewer treatments are becoming more accepted in the US as a treatment approach for select patients.44 Finally, proton therapy, which is typically a longer course of treatment, is also an available option and potentially carries lower risk of treatment-related toxicities.45,46 A national commercial claims database study found that from a payer’s perspective mean RT costs (in adjusted 2015 dollars) were $49,504, $57,244 and $115,501 for SBRT, a traditional long course, and proton therapy, respectively.45

Brachytherapy involves surgical implantation of radioactive seeds (low dose rate brachytherapy) or catheters for delivery of radioactive isotope (high dose rate brachytherapy) focally to the prostate gland in 1-4 treatments. Medicare reimbursements in 2014 were ~$10,000 for low dose rate and ~$10,000-20,000 for high dose rate.47

Estimating direct medical costs faced by US patients

Both prostate surgery and radiotherapy are expensive definitive therapies and no contemporary benchmarks exist for how US insurers currently share these costs with patients. However, nationally, we know that costs have increasingly shifted to patients in the form of more deductibles, coinsurance and copayments.48 The Kaiser Family Foundation estimates that in 2017, for hospital admissions, 64% of covered workers have coinsurance (average rate of 19%) and 12% have copayments, 10% have per diem hospital payments, 6% have copayment and coinsurance and 17% have no additional cost sharing assuming the general annual deductible has been met.48 These data suggest that insured patients also face the possibility of significant short-term OOP costs. Assuming $20,000 in reimbursement for a prostatectomy procedure has been negotiated by a hospital with an insurer, the average patient with coinsurance could be billed $3,800. Longer courses of radiation may increase patient OOP burdens since patients are typically billed for weekly status checks with their radiation oncologist.

There have been only few efforts to benchmark patients’ specific monetary responsibilities following treatment for localized disease and these must be interpreted in the context that these estimates were prepared prior to the US Affordable Care Act and thus likely underestimate contemporary obligations.

Jung et al. published a qualitative research study in 2012 of 41 men with clinically localized prostate cancer treated with prostatectomy (56%) or external beam RT (39%) in the prior 6-18 months at an academic medical center.35 Nearly all patients had employer-sponsored insurance (68%) or Medicare (17%) and patients recalled a median out-of-pocket expense over the prior 12 months of $640 (interquartile range of $270-1,500). These costs were incurred for treatment-related deductible and co-payment for treatment, supplies, medications and labs.

A larger study by Zheng et al. utilized the 2008 to 2012 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey data to assess excess self-reported direct medical expenditures on 1,170 prostate cancer survivors.49 They found that compared to age-matched controls without a cancer diagnosis, prostate cancer survivors had significantly greater incremental adjusted annual medical costs (nonelderly population: $3,586, 95% CI of $1,792-6,076; elderly population: $3,524, 95% CI = $1,539 to $5,909). While the magnitude of direct costs stayed relatively consistent across ages for prostate cancer patients, there were significant differences compared to other common cancers. For nonelderly survivors, prostate cancer direct costs were 30% and 59% lower compared to breast cancer (mean of $5,119, 95% CI = $3,439 to $7,158) or colorectal cancer (mean of $8,647, 95% CI = $4,932 to $13,974). For elderly survivors, prostate cancer-related direct costs were 29% lower than colorectal cancer (mean of $4,913, 95% CI = $2,768 to $7,470) but 54% greater than breast cancer (mean of $2,288, 95% CI = $814 to $3,995) survivors.

Markman and Luce performed a cross sectional study of patients treated between 2005 and 2008 which included 427 prostate cancer patients (77% early stage), three quarters of whom were treated within the prior 2 years. Since diagnosis, 18% of respondents reported $2,500-5,000 in OOP expenses and 20% of respondents reported over $5,000 (in 2008 US dollars).50

The only prospective direct cost estimate comes from a cohort study of 512 newly diagnosed, localized PCa patients treated between 2002-2005 at either an urban academic center or a Veterans Affairs hospital.51 Patients (69% or n=352 with radical prostatectomy, 31% or n=160 with external beam RT) completed baseline surveys and at 3, 6, 12, and 24 months of follow-up to estimate OOP direct as well as indirect costs for patients and caregivers. The OOP estimates are limited as they did not explicitly ask about costs of uncovered outpatient/inpatient care (which may reflect insurance trends from the early 2000s). Their survey assessed costs of medications and several non-medical direct costs including transportation, parking, meals and supplemental caregiving expenses. For both prostatectomy and RT, they reported that mean total OOP costs were less than $1,000 (in 2009 US dollars) at 3, 6, 12 and 24 months of follow-up. But, the patterns of cost differed between the two treatments. Likely reflective of the toxicity patterns, OOP costs post prostatectomy rise in the short term and then stabilize while RT-associated costs are initially lower but rise longer-term. For example, at 3 months post treatment, mean total OOP costs were $781 (standard error, SE = $2,284) vs. $532 (SE = $2,973) for prostatectomy and RT, respectively. For prostatectomy, the mean estimates fall to ~$400 and remain constant at 6, 12 and 24. Mean (SE) OOP costs at 1 year and 2 years post RT were $587 ($1,891) and $661 ($2,036), respectively. Using propensity score correction, the authors confirmed that initial costs were greater for prostatectomy but surgery was also associated with lower total costs and also lower medication costs but not indirect costs or non-medical costs.51

A patient’s insurance status will strongly influence their OOP burden. For example, an observational study investigating OOP healthcare expenditures for Medicare beneficiaries between 1997-2007 with and without cancer (including 22% prostate cancer patients, n=401) concluded that cancer patients faced nearly $1,000 more (in 2007 US dollars) in adjusted, annual incremental OOP spending.52 For beneficiaries with cancer, the median and mean total OOP burden as a share of annual income was 10% and 24%, respectively, suggesting some beneficiaries have much higher OOP burdens. The presence of supplemental insurance outside of primary Medicare as well as higher income were significant protectors against large OOP burden (defined as >20% of annual income). Greater assets, comorbid conditions and receipt of RT or any antineoplastic therapies were associated with greater hazard of large OOP burden.

We found no modern estimates for the cost to the patient for medications including androgen deprivation therapy or oral agents to address the symptoms of therapy (e.g., alpha antagonists or anticholinergics). Given that patients may require these medications for prolonged periods of time, the financial impact may compound.

International estimates of patients’ direct prostate cancer costs

Heterogeneity of global healthcare systems and reimbursement models make it difficult to draw cross-country comparisons, however the patterns of cost may offer some lessons. Presumably, objective OOP burdens experienced by patients should be lower in countries with greater healthcare access and medical expense coverage.

Gordon et al. performed a cross-sectional survey of 289 Australian men recruited electronically from prostate cancer support groups between April and June 201353 of self-reported OOP costs of prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment, changes in employment status and household finances. Men had been largely diagnosed in the prior 5 years (65%), the majority received prostatectomy (69%) and 20% of respondents had developed metastatic disease. In 2012 Australian dollars, the reported median total OOP expenditure since diagnosis was $8,000 (IQR $14,000). The distribution of OOP costs was strongly right skewed and 5% of patients reported more than $30,000. Of note, healthcare in Australia is a mixed system of public and private providers with most of care provided publicly; respondents with private insurance reported double the OOP costs compared to men with public insurance.

Healthcare systems like the Canadian model where medical costs are more completely reimbursed also highlight additional direct cost considerations. A Canadian study of 170 prostate cancer patients treated between 2008-2009 considered OOP costs on a more granular level.54 While less than 20% incurred significant OOP expenses (as defined by >7.5% of quarterly income), men with greater overall burden had above average travel costs.

The magnitude of the direct OOP costs must be interpreted in the patient’s broader financial context. A cross-sectional study of prostate and breast cancer survivors from the National Cancer Registry Ireland found that men with prostate cancer had significantly higher risk of cancer-related financial stress compared to the breast cancer survivors.55 Increased risk of stress was associated with the presence of pre-diagnosis financial stress, presence of mortgage or personal financial obligations, higher direct OOP costs, increased household expenses and having dependents. Ireland has a complex mixed public-private health care system where there is universal coverage, but most must pay fees for medical services and prescription drugs.

Direct costs: summary and open questions

Despite ample data on the costs of various treatment modalities at the payor level, there are few robust estimates of patient-level direct cost burden after prostate cancer treatment. Differences in the methodologies and time periods of data collection, as well as heterogeneity of healthcare systems, further complicate aggregated assessments. However, from these data, it is reasonable to conclude that men can face total OOP burdens of several thousand dollars post treatment with the potential for significantly greater sums. Patterns of OOP cost may be different by treatment modality – several reports suggest that while the bulk of the cost for both surgical and radiotherapeutic management occurs in the first year, the prostatectomy patients tend to have higher total costs in the immediate post-operative period due to the need for early interventions and a concentrated period of work loss (to be further discussed in next section). RT-related OOP costs might initially be lower but appear to rise over the first 2 years after treatment, reflective of the time course for side effects or the differing demographics of men undergoing RT (i.e., older patients with more general medical costs). There remains a need for additional studies to validate these findings in the contemporary insurance environment, to better enable clinicians or staff to provide evidence-based OOP estimates to patients. Ideally, these studies would be prospective and linked to financial toxicity screening instruments like COST.36

Indirect costs

Defining indirect costs

Indirect costs are the monetary value assigned to time spent receiving medical care, time recovering from illness or time lost due to premature death.40 These costs attempt to reflect lost “opportunity” and since these events are, by definition, not realized, indirect costs are always estimated. Indirect costs impact patients as well as caregiving family members and can be substantial. There are several components to indirect cost, including monetary losses due to workplace absenteeism, reduced productivity due to presenteeism (working while impaired due to cancer), lost income due to early retirement or cancer-related mortality.

While routine PSA screening remains controversial, following the AUA Guideline of shared decision making starting at age 5556 means that a significant proportion of men diagnosed with prostate cancer are likely to be fully employed. While the recovery from treatment and associated side effects are well known to impact cancer patients’ ability to work57 there has been limited study of the topic specifically for prostate cancer, especially in the US.

Impact of post-treatment employment disruptions

There have been several studies which have attempted to quantify changes in survivors’ employment status following prostate cancer treatment and some have used this information to estimate indirect cost burden. Bradley et al. used propensity scored matched prostate cancer patients aged 30-65 (n=267, 75% local disease) compared to controls to demonstrate that men with prostate cancer were significantly less likely to be working 6 months post diagnosis. Overall, men with prostate cancer were 10% (95% CI 3-18%) less likely to be working; patients treated with surgery were 17% (95% CI 8-25%) less likely while those treated with chemotherapy/radiation (these were not separated) were 11% (4-25%) less likely.58 Notably, the employment differences between prostate cancer patients and controls normalized by 12 months post treatment but around one quarter of men reported cancer-associated difficulties with job requirements requiring physical effort. Sixteen percent of men felt they could not keep pace at work. Relative to controls, men with prostate cancer were significantly more likely to retire from their jobs.

However, not all studies found significant impact on employment. Using the 2008 to 2012 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, with 1170 prostate cancer survivors, Zheng and colleagues reported more modest impact of treatment on employment losses.49 While non-elderly prostate cancer survivors had significant reduction numbers of missed work days compared to age-matched controls (mean of 2.7 days, 95% CI 1.1-5.1) this translated to a modest reduction in per capita productivity loss of $271 (95% CI $110-511). Compared to controls, prostate cancer survivors did not have significantly increased amounts of disability time or days spent at home, both of which were significantly increased for survivors of colorectal and breast cancer.

To assess prostate-cancer associated indirect costs, most reported studies have adopted a human capital approach which assumes that lost earnings are a proxy for lost output and generally multiplies incremental time lost from employment by wage per unit time.59 While commonly adopted, a potential concern with this approach is that from an economics perspective, while a patient’s absenteeism may reflect personal lost earnings, typically this does not translate to overall market productivity losses. The prospective study by Jayadevappa et al. used human capital methods to estimate indirect cost differences at various post-treatment time points following prostatectomy or RT. Indirect costs are most prominent in the first year after treatment, tend to be initially higher for prostatectomy patients but overall are no different for patients who receive surgery vs. radiotherapy.51 Higher estimates for postoperative patients are principally driven by more hours of missed work which support the hypothesis that younger patients have greater opportunity cost for prostate cancer treatment. SEER registry data suggests that men diagnosed with prostate cancer missed on average 27 days from work and men treated with hormone and/or radiation therapy or who were not treated missed fewer days from work (median of 3 days) relative to men undergoing surgery (median of 25 days).60

Quantifying the impact of caregiver support

The financial impact of prostate cancer is not limited to the patient. Yabroff and Kim used the human capital approach to quantify the value of informal “caregiver time,” which was opportunity time not spent pursuing usual activities including work or leisure.61 The study surveyed the principal patient-nominated caregivers of numerous cancer survivors between 2003-2006, 19% of which (n=130) had prostate cancer. In the entire cohort, around 80% had localized or regional disease but it was unclear how many prostate cancer patients were non-metastatic. The study had a broad definition of caregiving including emotional support, financial support, symptom management, personal care and transportation. In the two years following diagnosis, prostate cancer caregivers reported providing a mean of 12.5 (standard deviation, SD of 8) months of support on average 9 hours per day (SD of 9), though the frequency of support varied. Using the median national wage in 2006, they estimated the mean value of this prostate caregiver time to be roughly $45,000 (95% CI $36-54,000) annually.

Another study used a similar human capital approach to estimate the opportunity costs associated with lost productivity of 88 partner caregivers of localized prostate cancer patients. Opportunity cost was considered as reductions in the time caregivers worked and spent providing informal support). The estimated mean indirect burden at one year post diagnosis was around $6,000 (range $571-47,105 in 2009 dollars).62

International perspectives of indirect cost burden

The Australian cross-sectional study by Gordon et al. also surveyed men on employment impact and noted that 23% of men (n=64) reported that their prostate cancer care led to early retirement (mean of 4-5 years earlier than planned).53 Overall, 14% of men reduced their work hours as a result of their diagnosis. The opportunity costs of these employment changes were not quantified.

A group from Ontario, Canada assessed 585 long-term prostate cancer survivors (range 2-13 years from treatment) who presented to clinics or support groups to assess opportunity and direct OOP costs.63 Overall, mean indirect costs were $838/year and mean OOP costs were $200 per year (in 2006 Canadian dollars). Although generally low, it is important to note this represented approximately 10% of income for lower income patients. Radical prostatectomy, younger age, poor urinary function, current hormone therapy, and recent diagnosis were significantly associated with increased likelihood of incurring any costs, but only poorer urinary function significantly affected total (OOP plus indirect) amount. These results are likely related to the structure of the Canadian healthcare system where the government finances health insurance, but many rely on supplemental private insurance to help pay for prescription drugs.

Additional drivers of indirect cost

The indirect financial implications of a patient’s treatment decision are complex with the possibility for competing influences. For example, a recent National Cancer Database study found that even when adjusted for sociodemographic and clinical factors, patients with longer travel distance to a treatment center had greater odds of receiving SBRT compared to long course RT.64 The authors pose two sound, but contradictory, hypotheses for this observation including that patients with greater travel requirements have increased risk of financial toxicity with longer course radiotherapy due to travel costs, indirect costs of missed work, etc. An alternative explanation is that men with higher means who live further from the treatment center may have greater propensity to purposefully seek out SBRT. The authors interestingly theorize that younger men who are more likely to be fully employed may face the greatest opportunity costs between short and long course RT. Unlike other cancers which predominantly impact elderly adults, the frequent diagnosis of middle-aged men (who are likely actively working and may be the primary provider for their family) coupled with high cure rates of prostate cancer for both surgery and RT mean that treatment-related adverse events which impair productivity have the potential to result in substantial opportunity costs.

Indirect costs: summary and open questions

Much like for OOP costs, significant heterogeneity in how indirect costs are estimated and quantified challenges the ability to generalize patterns for the average prostate cancer patient. For example, inclusion of caregiver indirect costs has the potential to greatly impact overall familial burden but this is not routinely assessed. Most data suggest that men will have disruptions to their ability to work following treatment though estimates of the magnitude of the associated financial loss range significantly from several hundred dollars to tens of thousands (particularly if caregiver burden is included). There do seem to be hints that the patterns of indirect costs may be more concentrated in non-retired men and may differ by treatment type. Men recovering from prostate surgery are more likely to have short-term changes to their work attendance while the subacute development of RT-associated side effects may cause more delayed absenteeism.

Prospective intervention studies can feasibly include estimates of indirect costs.65 Going forward, the usage of a standardized instrument would likely be of benefit. One possibility is the Institute for Medical Technology Assessment Productivity Cost Questionnaire (iMTA iPCQ) which is an objective tool to measure productivity losses of paid work as a result of absenteeism.66 This has been proposed as standardized instrument to quantify opportunity costs11 but to our knowledge, has not been specifically utilized for prostate cancer.

Patient specific values

Patient-level predictors of greater financial toxicity risk

The aforementioned financial metrics must be interpreted using a patient’s qualitative context and triggers of psychological distress. This is poorly categorized for localized prostate cancer but a few studies offer hints of various predictors of those who are most likely to report financial distress.

Jung and colleagues performed semi-structured interviews of a small cohort (n=41) of insured patients treated for localized prostate cancer in the prior 6-18 months at an academic medical center. They found a fairly modest share of patients (24%) who reported significant burden from their OOP financial responsibilities.35 One in five respondents reported a need to reduce non-medical spending or make other sacrifices to afford prostate cancer treatment. Those who expressed greater subjective burden predominantly reported an OOP expense of at least $1,500 over the prior 12 months, had annual incomes <$60,000 and demographically were more likely to be black and have less than a college education. These results should be interpreted in the context that this population was a small sample of generally white and relatively affluent patients. Despite these caveats, there was a small group of insured patients (3 of 9 total patients who reported subjective burden) who had middle class incomes, therefore the risk of prostate cancer related financial toxicity is likely not limited to marginalized or low-income patients. Given that the average American family has less than $5,000 in bank accounts67, the occurrence of treatment-related financial distress may be more common than most providers appreciate.

Association of financial toxicity with treatment-related side effects

It is very likely that post-treatment complications or persistent symptoms impact a patient’s risk of financial toxicity. The prospective assessment of OOP and indirect costs showed that greater total cost burden is inversely correlated with health-related quality of life, including the prostate-specific domains including urinary, bowel and sexual function or bother.51 This association is probably due to several factors such as greater need for physician visits and supportive care medications, and the possibility of dissatisfaction with their treatment choice in the context of unanticipated side effects. This association is non-trivial since each of the treatment options has significant risk of distinct quality of life impairments.68

Furthermore, a causal link between patient reported health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and his subsequent satisfaction with care has been established in newly diagnosed prostate cancer.69 In other words, lower overall satisfaction with prostate cancer care tends to be a consequence of lower scores on patient-reported symptom assessment scales (e.g., SF-36 and UCLA-PCI). If a patient is dissatisfied with his treatment choice, it is probable that he would feel relatively more burdened by its financial impact.

Patient specific values: summary and open questions

The identification of demographic or clinical predictors of financial toxicity would be helpful to enable clinicians to tailor their discussions with the most at risk patients. But, even if better estimates of possible patient-level financial burdens associated with each particular treatment option were readily available, specific OOP thresholds which put patients at risk for financial toxicity likely will not be possible to generalize. Early signals suggest that financial toxicity is more prevalent in historically disenfranchised groups (e.g., older men, lower socioeconomic status, ethnic minorities particularly African Americans) but not exclusively. Several reports show that even very modest OOP burdens can trigger financial strain. One of the more consistent findings is that persistent quality of life impairments are associated with increased risk of financial toxicity. Quality of life can be described in many ways, but the data consistently suggest that men with sustained urinary, sexual or bowel dysfunction either due to, or not resolved from, their treatment are at greater risk of financial distress. While causality is difficult to discern from cross-sectional or even cohort designs, the drivers of this association are likely both monetary (i.e., due to frequent interaction with the healthcare system) and psychological due to dissatisfaction.

Expectations of possible financial burdens

Across oncology, there is growing enthusiasm for increased transparency with patients regarding the costs of their care as part of shared decision-making.70 With respect to localized prostate cancer, the joint AUA/ASTRO/SUO guidelines from 2017 strongly advocate that patient counseling should “incorporate shared decision making and explicitly consider cancer severity (risk category), patient values and preferences, life expectancy, pre-treatment general functional and genitourinary symptoms, expected post-treatment functional status, and potential for salvage treatment.”71 While prostate cancer patients’ values are heterogeneous, there are likely many for whom even a small possibility of significant financial burden would resonate.

There are calls for urologists and radiation oncologists to play a more prominent role in discussing financial topics with their patients,72 though at present it remains unclear how often these types of conversations are occurring. Evidence from other types of cancer and advanced stage disease suggest they are likely infrequent. Benchmarking of 167 practicing medical oncologists from over a decade ago revealed that less than half of medical oncologists regularly discussed costs with their patients and cited several barriers to these discussions, including physician discomfort, lack of solutions, lack of knowledge, and uncertainty about whether the topic would be negatively perceived by the patient.73 A more recent study which analyzed transcriptions of 677 clinic encounters from an outpatient breast cancer clinic found that cost conversations occurred in about 20% of encounters and were initiated by medical oncologists 59% of the time.74 These conversations were generally less than one minute and covered a wide range of topics including drug and diagnostic prices.

Importantly, clinicians’ potential concern that financial discussions jeopardize patient-provider relationships seems to be unfounded.75 In, a pilot study of 107 metastatic breast, lung and colorectal cancers, researchers discussed potential costs associated with chemotherapy at the time of consultation. While the minority (28%) of oncologists felt comfortable discussing costs, most patients (80%) wanted to have these conversations. Eighty percent of patients had no negative feelings about hearing cost information.

Patients’ knowledge of potential costs may not significantly impact treatment decision making

While patients may find cost information helpful, an important open question is whether this data actually influences decision making. In general, men have poor awareness of possible costs prior to making a treatment decision. But, this may be largely inconsequential since patients, even those with subjective financial toxicity, have tended to minimize the importance of cost when choosing a treatment. The qualitative study by Jung et al. of 41 localized prostate cancer patients noted poor awareness of possible OOP costs prior to treatment decision making.35 Eighty percent of patients (33 of 41) reported that they “knew little” or “did not know” their anticipated OOP costs prior to choosing a specific treatment. But in this population, the majority of respondents (38 of 41, 93%), including most who reported high subjective financial burden, stated they would not have altered their treatment choice even if better informed of possible costs. The authors synthesized a few other themes from respondents, including that most men did not consider costs since they felt well-insured and that treatment efficacy or the physician’s recommendation should dominate cost in making a treatment decision.35 Interestingly, 17% of respondents felt that it was inappropriate or irrelevant for their physician to be discussing OOP costs, instead they preferred a focus on “medical” topics.

These results agree with the findings of a 2010 cross sectional study of 427 mostly early stage prostate cancer patients where only 7% of respondents reported a “large amount” of financial stress due to the cost of treatment.50 Interestingly, the degree of “financial distress” was significantly lower than for breast, colorectal or lung cancer patients who reported 19%, 25% and 27% financial stress, respectively. These data hint the interesting possibility that prostate cancer patients are in general less prone to financial toxicity. Survivors of prostate cancer had relatively lower OOP costs and productivity loss compared to other common cancers.49

Potential explanations for lower financial toxicity among men with prostate cancer is that many men diagnosed with localized prostate cancer are relatively healthy prior to treatment, overall low incidence of severe side effects, relatively low utilization (historically) of oral anti-cancer agents or behavioral reticence of males to admit financial distress. While intriguing, these studies predate insurers’ significant shifts in cost burden to patients, therefore their contemporary interpretation is unclear; a low prevalence of prostate-cancer financial toxicity would make better benchmarking even more critical to distinguish those most at risk.

Limited knowledge of potential costs is not limited to the US patient population

Gordon et al.’s Australian cross-sectional study of 289 mostly localized prostate cancer patients found that approximately 70% of respondents had spent more on their cancer treatment than they had expected to; 20% stated that the cost of treatment caused a “great deal” of distress which was more concentrated in respondents who had been more recently diagnosed.53

A Canadian study (n=170 prostate cancer patients) reported that nearly 20% of surveyed prostate cancer patients had significant OOP costs in the 3 months leading up to the survey date and while these costs significantly increased stress, they did not significantly impact treatment decisions.54 Of note, only about a quarter of surveyed patients informed their physician about their OOP costs and a minority of patients was aware of any financial support or assistance options.

Expectations of financial burdens: summary and open questions

Oncology patients are increasingly seeking information about the potential costs of their potential treatments and are comfortable having these conversations with their clinicians. Clinicians have historically been reluctant to initiate these discussions for a multitude of reasons but this may soon be unacceptable to patients in an era of greater medical cost transparency. Interestingly, while men may request more cost information, there is some evidence to suggest that these figures may not factor strongly in their prostate cancer treatment decision-making process. Outside of validating this hypothesis, additional opportunities for further research exist including the development of strategies for effective preemptive communication of medical cost data with prostate cancer patients.

Key learnings and emerging themes

In general, our review of the existent literature reveals that the potential adverse effects of financial strain remain poorly studied in the prostate cancer context. We suspect that increased attention of this topic across oncology will result in providers’ heightened responsibility to acknowledge and address this issue proactively with patients. The success of these conversations with men facing prostate cancer treatment decisions necessitates more robust study of benchmarks and predictors of financial strain reflective of the contemporary healthcare system.

Despite the caveat, our review identified several early themes which can help tailor physicians’ pre-treatment financial counseling efforts. There is a potential for significant direct and indirect cost burden after both surgery or RT. It is probable that baseline disenfranchisement prognosticates greater risk of financial toxicity, but this is neither universal nor the sole cause. Effective efforts to identify men at risk will likely need broader screening methods and certainly should focus heavily on men with persistent treatment-related quality of life decrements. A man’s treatment modality will likely also influence what type of post-treatment screening is optimal – post prostatectomy patients likely have greater risk in the first months after surgery whereas those who completed RT may have persistent risk for years.

Lastly, we speculate that prostate cancer patients may have lower overall risk of financial toxicity compared to other common cancers. Limited qualitative efforts of prostate cancer patients suggest that many men want their decision to be agnostic of financial factors and may not readily report feeling particularly strained by the costs of their subsequent care. The possibility that this is a broader trend would be an important finding that certainly warrants exploration.

Conclusions and future directions

Financial toxicity is increasingly recognized as a serious potential consequence of cancer diagnosis and treatment. Increased financial strain has been associated with numerous poor prognostic factors including worsened survival and thus may truly be considered akin to other treatment-related toxicities. Focusing on prostate cancer, next steps must include prospective studies using validated tools to assess the extent of financial distress and identify specific predictors of risk. These efforts would better prepare clinicians with salient messaging to engage their patients on this topic.

Possible interventions to mitigate or address financial toxicity have been suggested76–78, however many pertain to rising drug or systemic therapeutic costs. Our proposed Financial Toxicity Framework not only enables clinicians to methodically assess a patient’s risk of financial toxicity, but also suggests broad categories for intervention. For example, the development of practical communication tools for men to proactively discuss with their employers may minimize the impact of treatment-related workplace absenteeism (and thus indirect costs). Another option is that consideration of more financially prudent interventions could be considered more routinely for men with sustained post-treatment side effects (e.g., tele-health appointments, bundling of several visits on the same day, automatic referral to social work). In the US, addressing possible financial strain caused by definitive procedural costs due to surgery or radiotherapy may prompt more consideration of novel reimbursement schemes like bundled payments or episode-based payment models79,80

We conclude by appreciating that as with many concepts in medicine, a single strategy is unlikely to be effective. Recognition that treatment-related costs may negatively impact patient outcomes is the first step but successful integration into an already time-constrained clinical flow will require a multidisciplinary commitment. The urologist or radiation oncologist can acknowledge the risk but must work closely with nurses, social workers, patient service representatives or financial counselors to identify and support patients most likely to be impacted.

Review criteria

Electronic searches of several research databases including PubMed and the Cochrane Library were conducted. A search strategy was developed in collaboration with an experienced medical librarian. The search string was initially developed for PubMed and later adapted for other databases. Our research goal was to clarify the prevalence and potential drivers of patient-level financial strain for men diagnosed with non-metastatic prostate cancer. Our search string was purposefully broad given our experience that heterogeneous descriptors are often used in the literature. No restrictions were made with respect to non-empirical studies such as literature reviews or conference abstracts. The search string was restricted to English language only but not by date of publication. Titles of identified studies were then manually screened to exclude irrelevant titles. This was followed by a secondary abstract review by the authors to ensure relevance to our research objective. Finally, following full-text review of selected sources, the references were cross-referenced with the database results to identify additional potentially relevant resources.

Key points.

The term financial toxicity broadly reflects the financial consequences and subjective burden resulting from a cancer diagnosis and treatment

Financial toxicity is increasingly recognized in oncology but has been poorly studied in the context of prostate cancer

We hypothesize that a strong risk of developing financial distress may influence a man’s treatment decision though no guidelines recommend explicit discussion of this topic

A prostate cancer patient’s risk of developing financial toxicity is multifactorial and likely influenced by direct costs, indirect costs, a patient’s economic baseline, patient-specific values and upfront expectations

There is likely differential risk of developing financial toxicity depending on the treatment approach; surgery and radiotherapy are more likely to influence short-term, and longer-term risk, respectively

We speculate that the overall risk of financial toxicity may be lower for men with prostate cancer compared to other cancers, however men with persistent treatment-related toxicities are likely higher risk

Acknowledgement:

The authors thank Johanna Goldberg, MSLIS for graciously assisting with our research database queries and for providing suggestions on literature review best practices.

Funding: BSI received a Resident Seed Grand from the American College of Radiation Oncology (ACRO). This research was also funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748.

Footnotes

Competing interests/Disclosures: Ehdaie – Speaker, Myriad Genetics, Inc Medical Advisory Board; Principal Investigator, Phase 2 Trial of MR-guided HIFU in Intermediate Risk Prostate Cancer. All other authors – none.

References

- 1.National Cancer Institute SEER Program. Prostate Cancer - Cancer Stat Facts. Prostate Cancer - Cancer Stat Facts (2018). Available at: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/prost.html. (Accessed: 10th September 2018)

- 2.Showalter TN, Mishra MV & Bridges JF Factors that influence patient preferences for prostate cancer management options: A systematic review. Patient Prefer Adherence 9, 899–911 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sidana A et al. Treatment Decision-Making for Localized Prostate Cancer: What Younger Men Choose and Why. Prostate 72, 58–64 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu J, Dailey RK, Eggly S, Neale AV & Schwartz KL Men’s Perspectives on Selecting Their Prostate Cancer Treatment. J Natl Med Assoc 103, 468–478 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bosco JLF, Halpenny B & Berry DL Personal preferences and discordant prostate cancer treatment choice in an intervention trial of men newly diagnosed with localized prostate cancer. Health Qual Life Outcomes 10, 123 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zafar SY & Abernethy AP Financial Toxicity, Part I: A New Name for a Growing Problem. Oncology (Williston Park) 27, 80–149 (2013). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meropol NJ et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology Guidance Statement: The Cost of Cancer Care. JCO 27, 3868–3874 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schroeck FR et al. Cost of New Technologies in Prostate Cancer Treatment: Systematic Review of Costs and Cost Effectiveness of Robotic-assisted Laparoscopic Prostatectomy, Intensity-modulated Radiotherapy, and Proton Beam Therapy. Eur. Urol. 72, 712–735 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hartman M, Martin AB, Espinosa N, Catlin A & The National Health Expenditure Accounts Team. National Health Care Spending In 2016: Spending And Enrollment Growth Slow After Initial Coverage Expansions. Health Affairs 37, 150–160 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilligan AM, Alberts DS, Roe DJ & Skrepnek GH Death or Debt? National Estimates of Financial Toxicity in Persons with Newly-Diagnosed Cancer. Am. J. Med. 131, 1187–1199.e5 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gordon LG, Merollini KMD, Lowe A & Chan RJ A Systematic Review of Financial Toxicity Among Cancer Survivors: We Can’t Pay the Co-Pay. Patient 10, 295–309 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lathan CS et al. Association of Financial Strain With Symptom Burden and Quality of Life for Patients With Lung or Colorectal Cancer. JCO 34, 1732–1740 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharp L, Carsin A-E & Timmons A Associations between cancer-related financial stress and strain and psychological well-being among individuals living with cancer. Psychooncology 22, 745–755 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meeker CR et al. Relationships Among Financial Distress, Emotional Distress, and Overall Distress in Insured Patients With Cancer. J Oncol Pract 12, e755–764 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fenn KM et al. Impact of financial burden of cancer on survivors’ quality of life. J Oncol Pract 10, 332–338 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zafar SY et al. Population-based assessment of cancer survivors’ financial burden and quality of life: a prospective cohort study. J Oncol Pract 11, 145–150 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramsey SD et al. Financial Insolvency as a Risk Factor for Early Mortality Among Patients With Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 34, 980–986 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zafar SY et al. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: a pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient’s experience. Oncologist 18, 381–390 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaisaeng N, Harpe SE & Carroll NV Out-of-pocket costs and oral cancer medication discontinuation in the elderly. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 20, 669–675 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hess LM et al. Factors Associated with Adherence to and Treatment Duration of Erlotinib Among Patients with Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 23, 643–652 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marchetti B, Spinola PG, Pelletier G & Labrie F A potential role for catecholamines in the development and progression of carcinogen-induced mammary tumors: hormonal control of beta-adrenergic receptors and correlation with tumor growth. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 38, 307–320 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao XY et al. Glucocorticoids can promote androgen-independent growth of prostate cancer cells through a mutated androgen receptor. Nat. Med. 6, 703–706 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thaker PH et al. Chronic stress promotes tumor growth and angiogenesis in a mouse model of ovarian carcinoma. Nat. Med. 12, 939–944 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sood AK et al. Stress hormone-mediated invasion of ovarian cancer cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 12, 369–375 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bullock AJ, Hofstatter EW, Yushak ML & Buss MK Understanding Patients’ Attitudes Toward Communication About the Cost of Cancer Care. J Oncol Pract 8, e50–e58 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jagsi R et al. Unmet Need for Clinician Engagement Regarding Financial Toxicity After Diagnosis of Breast Cancer. Cancer (2018). doi: 10.1002/cncr.31532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Faiena I et al. Regional Cost Variations of Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy Compared With Open Radical Prostatectomy. Clin Genitourin Cancer 13, 447–452 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parthan A et al. Comparative Cost-Effectiveness of Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy Versus Intensity-Modulated and Proton Radiation Therapy for Localized Prostate Cancer. Front Oncol 2, (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.James ND et al. Abiraterone for Prostate Cancer Not Previously Treated with Hormone Therapy. New England Journal of Medicine 377, 338–351 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koopmanschap MA & Rutten FF Indirect costs in economic studies: confronting the confusion. Pharmacoeconomics 4, 446–454 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chino F et al. Going for Broke: A Longitudinal Study of Patient-Reported Financial Sacrifice in Cancer Care. J Oncol Pract JOP 1800112 (2018). doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chino F et al. Out-of-Pocket Costs, Financial Distress, and Underinsurance in Cancer Care. JAMA Oncol 3, 1582–1584 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Henrikson NB, Tuzzio L, Loggers ET, Miyoshi J & Buist DS Patient and oncologist discussions about cancer care costs. Support Care Cancer 22, 961–967 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zafar SY et al. The utility of cost discussions between patients with cancer and oncologists. Am J Manag Care 21, 607–615 (2015). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jung OS et al. Out-of-pocket expenses and treatment choice for men with prostate cancer. Urology 80, 1252–1257 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Souza JA et al. The development of a financial toxicity patient-reported outcome in cancer: The COST measure. Cancer 120, 3245–3253 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prawitz A et al. Incharge Financial Distress/Financial Well-Being Scale: Development, Administration, and Score Interpretation. (Social Science Research Network, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huntington SF et al. Financial toxicity in insured patients with multiple myeloma: a cross-sectional pilot study. Lancet Haematol 2, e408–416 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Souza JA et al. Measuring financial toxicity as a clinically relevant patient-reported outcome: The validation of the COmprehensive Score for financial Toxicity (COST). Cancer 123, 476–484 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yabroff KR, Lund J, Kepka D & Mariotto A Economic Burden of Cancer in the US: Estimates, Projections, and Future Research. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 20, 2006–2014 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.The Effect of Eliminating the Individual Mandate Penalty and the Role of Behavioral Factors | Commonwealth Fund. Available at: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2018/jul/eliminating-individual-mandate-penalty-behavioral-factors. (Accessed: 10th September 2018)

- 42.Laviana AA et al. Utilizing time-driven activity-based costing to understand the short- and long-term costs of treating localized, low-risk prostate cancer. Cancer 122, 447–455 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pate SC, Uhlman MA, Rosenthal JA, Cram P & Erickson BA Variations in the open market costs for prostate cancer surgery: a survey of US hospitals. Urology 83, 626–630 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kishan AU & King CR Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy for Low- and Intermediate-Risk Prostate Cancer. Semin Radiat Oncol 27, 268–278 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pan HY et al. Comparative Toxicities and Cost of Intensity-Modulated Radiotherapy, Proton Radiation, and Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy Among Younger Men With Prostate Cancer. JCO 36, 1823–1830 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chuong MD et al. Minimal toxicity after proton beam therapy for prostate and pelvic nodal irradiation: results from the proton collaborative group REG001-09 trial. Acta Oncol 57, 368–374 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lanni T et al. Comparing the Cost-Effectiveness of Low-Dose-Rate Brachytherapy, High-Dose-Rate Brachytherapy, and Hypofactionated Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy for the Treatment of Low-/Intermediate-Risk Prostate Cancer. International Journal of Radiation Oncology • Biology • Physics 90, S587–S588 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 48.2017 Employer Health Benefits Survey - Section 7: Employee Cost Sharing. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zheng Z et al. Annual Medical Expenditure and Productivity Loss Among Colorectal, Female Breast, and Prostate Cancer Survivors in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst 108, (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Markman M & Luce R Impact of the Cost of Cancer Treatment: An Internet-Based Survey. J Oncol Pract 6, 69–73 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jayadevappa R et al. The burden of out-of-pocket and indirect costs of prostate cancer. Prostate 70, 1255–1264 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Davidoff AJ et al. Out-of-pocket health care expenditure burden for Medicare beneficiaries with cancer. Cancer 119, 1257–1265 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gordon LG et al. Financial toxicity: a potential side effect of prostate cancer treatment among Australian men. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 26, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Housser E et al. Responses by breast and prostate cancer patients to out-of-pocket costs in Newfoundland and Labrador. Curr Oncol 20, 158–165 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sharp L & Timmons A Pre-diagnosis employment status and financial circumstances predict cancer-related financial stress and strain among breast and prostate cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 24, 699–709 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Carter HB et al. Early detection of prostate cancer: AUA Guideline. J. Urol. 190, 419–426 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mehnert A Employment and work-related issues in cancer survivors. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 77, 109–130 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bradley CJ, Neumark D, Luo Z, Bednarek H & Schenk M Employment Outcomes of Men Treated for Prostate Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 97, 958–965 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ratcliffe J The measurement of indirect costs and benefits in health care evaluation: a critical review. Project Appraisal 10, 13–18 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bradley CJ, Oberst K & Schenk M Absenteeism from work: the experience of employed breast and prostate cancer patients in the months following diagnosis. Psychooncology 15, 739–747 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yabroff KR & Kim Y Time costs associated with informal caregiving for cancer survivors. Cancer 115, 4362–4373 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li C et al. Burden among partner caregivers of patients diagnosed with localized prostate cancer within 1 year after diagnosis: an economic perspective. Support Care Cancer 21, 3461–3469 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.de Oliveira C et al. Patient time and out-of-pocket costs for long-term prostate cancer survivors in Ontario, Canada. J Cancer Surviv 8, 9–20 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mahal BA et al. Travel distance and stereotactic body radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. Cancer 124, 1141–1149 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Burns R, Wolstenholme J, Leslie T & Hamdy F Enhancing prostate cancer trial design by incorporating robust economic analysis: Lessons learned from the UK part feasibility study. European Journal of Surgical Oncology 44, S33 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bouwmans C et al. The iMTA Productivity Cost Questionnaire: A Standardized Instrument for Measuring and Valuing Health-Related Productivity Losses. Value Health 18, 753–758 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. 2016 Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) Chartbook. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sanda MG et al. Quality of Life and Satisfaction with Outcome among Prostate-Cancer Survivors. New England Journal of Medicine 358, 1250–1261 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jayadevappa R, Schwartz JS, Chhatre S, Wein AJ & Malkowicz SB Satisfaction with Care: A Measure of Quality of Care in Prostate Cancer Patients. Med Decis Making 30, 234–245 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wollins DS & Zafar SY A Touchy Subject: Can Physicians Improve Value by Discussing Costs and Clinical Benefits With Patients? Oncologist 21, 1157–1160 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sanda MG et al. Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer: AUA/ASTRO/SUO Guideline. Part I: Risk Stratification, Shared Decision Making, and Care Options. J. Urol. (2017). doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2017.11.095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mossanen M & Smith AB Addressing Financial Toxicity: The Role of the Urologist. J. Urol. 200, 43–45 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schrag D & Hanger M Medical oncologists’ views on communicating with patients about chemotherapy costs: a pilot survey. J. Clin. Oncol. 25, 233–237 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hunter WG et al. Discussing Health Care Expenses in the Oncology Clinic: Analysis of Cost Conversations in Outpatient Encounters. JOP 13, e944–e956 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kelly RJ et al. Patients and Physicians Can Discuss Costs of Cancer Treatment in the Clinic. J Oncol Pract 11, 308–312 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zafar SY & Abernethy AP Financial toxicity, Part II: how can we help with the burden of treatment-related costs? Oncology (Williston Park, N.Y.) 27, 253–254, 256 (2013). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zafar SY, Newcomer LN, McCarthy J, Fuld Nasso S & Saltz LB How Should We Intervene on the Financial Toxicity of Cancer Care? One Shot, Four Perspectives. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 37, 35–39 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tran G & Zafar SY Financial toxicity and implications for cancer care in the era of molecular and immune therapies. Ann Transl Med 6, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Teckie S, Rudin B, Chou H, Stanzione R & Potters L Creation of an Episode-Based Payment Model for Prostate and Breast Cancer Radiation Therapy. International Journal of Radiation Oncology • Biology • Physics 99, E417–E418 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ellimoottil C et al. Episode-based Payment Variation for Urologic Cancer Surgery. Urology 111, 78–85 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]