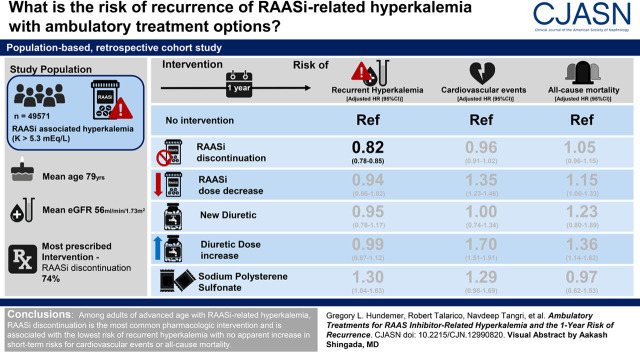

Visual Abstract

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, epidemiology and outcomes, electrolytes, renin, clinical nephrology, hyperkalemia, renin-angiotensin system, recurrence

Abstract

Background and objective

The optimal ambulatory management of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitor (RAASi)–related hyperkalemia to reduce the risk of recurrence is unknown. We examined the risk of hyperkalemia recurrence on the basis of outpatient pharmacologic changes following an episode of RAASi-related hyperkalemia.

Design

We performed a population-based, retrospective cohort study of older adults (n=49,571; mean age 79 years) who developed hyperkalemia (potassium ≥5.3 mEq/L) while on a RAASi and were grouped as follows: no intervention, RAASi discontinuation, RAASi dose decrease, new diuretic, diuretic dose increase, or sodium polystyrene sulfonate within 30 days. The primary outcome was hyperkalemia recurrence, with secondary outcomes of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality within 1 year.

Results

Among patients who received a pharmacologic intervention (23% of the cohort), RAASi discontinuation was the most commonly prescribed strategy (74%), followed by RAASi decrease (15%), diuretic increase (7%), new diuretic (3%), and sodium polystyrene sulfonate (1%). A total of 16,977 (34%) recurrent hyperkalemia events occurred within 1 year. Compared with no intervention (35%, referent), the cumulative incidence of recurrent hyperkalemia was lower with RAASi discontinuation (29%; hazard ratio, 0.82; 95% confidence interval, 0.78 to 0.85), whereas there was no difference with RAASi dose decrease (36%; hazard ratio, 0.94; 95% confidence interval, 0.86 to 1.02), new diuretic (32%; hazard ratio, 0.95; 95% confidence interval, 0.78 to 1.17), or diuretic increase (38%; hazard ratio, 0.99; 95% confidence interval, 0.87 to 1.12) and a higher incidence with sodium polystyrene sulfonate (55%; hazard ratio, 1.30; 95% confidence interval, 1.04 to 1.63). RAASi discontinuation was not associated with a higher risk of 1-year cardiovascular events (hazard ratio, 0.96; 95% confidence interval, 0.91 to 1.02) or all-cause mortality (hazard ratio, 1.05; 95% confidence interval, 0.96 to 1.15) compared with no intervention.

Conclusions

Among older adults with RAASi-related hyperkalemia, RAASi discontinuation is associated with the lowest risk of recurrent hyperkalemia, with no apparent increase in short-term risks for cardiovascular events or all-cause mortality.

Introduction

Hyperkalemia is a common clinical scenario associated with significant morbidity and mortality, including muscle weakness or paralysis, cardiac conduction disturbances, cardiac arrhythmias, and sudden death (1–5). Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors (RAASis) are among the most common causes of hyperkalemia population wide (6–8). These evidence-based medications are commonly prescribed to patients with CKD, diabetes mellitus, and/or congestive heart failure, conditions with the potential to further amplify the risks for hyperkalemia in and of themselves (9–12).

Although severe hyperkalemia is a medical emergency typically requiring urgent in-hospital intervention, mild to moderate hyperkalemia is often managed in the ambulatory setting (13). Prior to the introduction of newer potassium-binding agents, the most common ambulatory pharmacologic treatment changes for hyperkalemia include discontinuation or dose decrease of RAASi, initiation or dose increase of potassium-wasting diuretics (i.e., thiazide and loop diuretics), or initiation of potassium-binding medications (e.g., sodium polystyrene sulfonate [SPS]). Which ambulatory intervention is selected varies widely by provider, and to date, there are no randomized controlled trials on the comparative effectiveness of these common treatment options for RAASi-related hyperkalemia (6).

As such, we examined the 1-year risk of hyperkalemia recurrence on the basis of outpatient prescription changes in patients after an episode of RAASi-related hyperkalemia in older (≥66-years) adults. The prescription changes consisted of no intervention (i.e., continuing RAASi at the same dose with no other pharmacologic intervention), RAASi discontinuation, RAASi dose decrease, new diuretic, diuretic dose increase, or SPS within 30 days. We further examined the 1-year risk of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality between these interventions.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Setting

We conducted a population-level, retrospective cohort study of older adults (≥66 years of age) in Ontario, Canada prescribed an RAASi who developed hyperkalemia using linked databases. These datasets were linked using unique encoded identifiers and analyzed at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES). Ontario is Canada’s largest province with over 14.6 million residents, 16% of which are 65 years of age or older (14). All Ontario residents have access to universal public health care, with drug coverage for patients over the age of 65. The use of deidentified data in this project was authorized under section 45 of Ontario’s Personal Health Information Protection Act, which does not require review by a research ethics board. The reporting of this study follows guidelines for observational studies (Supplemental Table 1) (15).

Data Sources

We ascertained patient characteristics, medication data, and outcome data from linked databases using unique encoded identifiers and analyzed at ICES. Demographics and vital status information were obtained from the Ontario Registered Persons Database. Medication information was obtained from the Ontario Drug Benefit Claims database. This database contains highly accurate records of all outpatient prescriptions dispensed to patients aged 65 or older, with an error rate of <1% (16). Diagnostic and procedural information from all hospitalizations was determined using the Canadian Institute for Health Information Discharge Abstract Database. Diagnostic information from emergency room visits was determined using the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System. Information was also obtained from the Ontario Health Insurance Plan database, which contains all health claims for inpatient and outpatient physician services. Whenever possible, we defined patient characteristics and outcomes using validated codes (Supplemental Table 2). Laboratory information is contained in the Ontario Laboratory Information System, which captures laboratory tests for patients in Ontario. The databases were complete for all variables used except for rural location and income, which were missing in <0.5% of patients. The only reason for lost follow-up was emigration from the province, which occurs in <0.5% of residents each year (17).

Cohort Definition

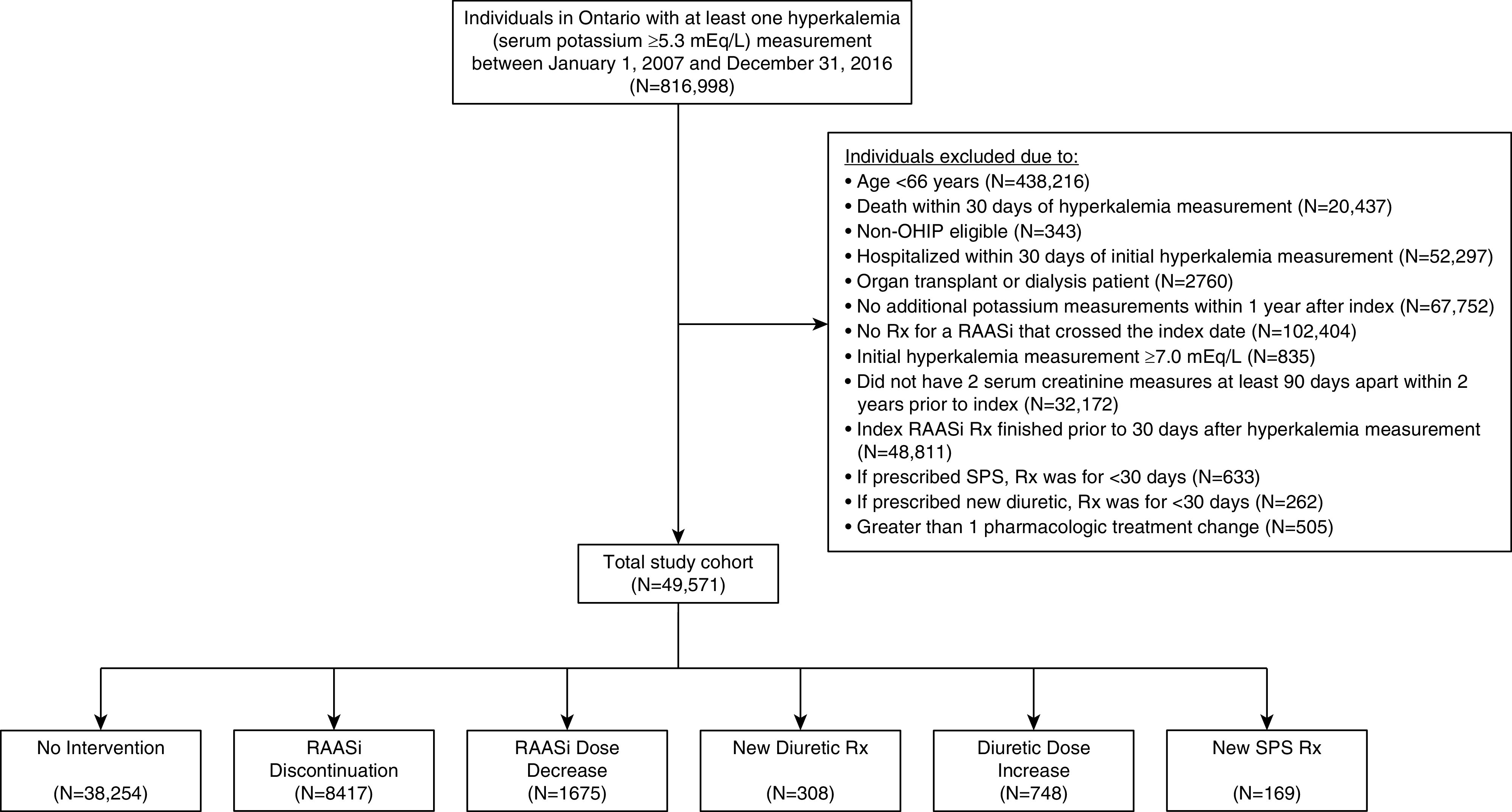

All Ontario residents ≥66 years of age treated with an RAASi with at least one outpatient hyperkalemia measurement (defined as serum potassium ≥5.3 mEq/L) between January 1, 2007 and December 31, 2016 were included, with a maximum follow-up date of December 31, 2017 (Figure 1). Prescription drug information is available for all adults ≥65 years of age in Ontario, and we initiated our cohort at age 66 to allow for a 1-year look-back period for preexisting medications. Patients were included if no identified outpatient intervention was performed (i.e., RAASi was continued at the same dose with no other pharmacologic intervention to treat hyperkalemia) or if they had one of the following interventions performed within 30 days of the initial hyperkalemia measurement: (1) RAASi discontinuation, (2) RAASi dose decrease, (3) new diuretic prescription, (4) diuretic dose increase, or (5) new SPS prescription. Prescriptions of SPS and/or diuretics initiated in the emergency department only were not considered in the analysis. Patients were excluded if they had more than one outpatient intervention performed, were on dialysis, had a history of kidney transplantation, had fewer than two serum creatinine measurements at least 90 days apart within 2 years prior to index, died or were hospitalized within 30 days of the initial hyperkalemia measurement, had no repeat potassium measurements, or had an initial hyperkalemia measurement ≥7.0 mEq/L. Additionally, patients given a new prescription for SPS or a diuretic were excluded if the prescription was for <30 days to exclude patients receiving a very short course. To exclude acute hyperkalemia and avoid an immortal time bias, the index date was defined as 30 days after the hyperkalemia test date (18).

Figure 1.

Flow chart for cohort assembly. OHIP, Ontario Health Insurance Plan; RAASi, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitor; Rx, prescription; SPS, sodium polystyrene sulfonate.

Exposure

We compared six mutually exclusive hyperkalemia management strategies as follows: (1) no intervention (i.e., continuing RAASi at the same dose with no other pharmacologic intervention), (2) RAASi discontinuation, (3) RAASi dose decrease, (4) new diuretic prescription, (5) diuretic dose increase, or (6) new SPS prescription. RAASi medications included angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, and epithelial sodium channel inhibitors. Diuretics included loop and thiazide diuretics. A complete list of exposure medications included is in Supplemental Table 3.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was recurrence of hyperkalemia (serum potassium ≥5.3 mEq/L) within 1 year. Secondary outcomes included cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality within 1 year. Cardiovascular events included an acute coronary event/cardiac revascularization (coronary artery bypass graft or percutaneous coronary intervention), stroke/transient ischemic attack, and congestive heart failure.

Statistical Analyses

We examined baseline characteristics by the six hyperkalemia treatment strategies (no intervention, RAASi discontinuation, RAASi dose decrease, new diuretic prescription, diuretic dose increase, and new SPS prescription). We plotted the cumulative incidence of recurrent hyperkalemia for each of the exposure groups within 1 year from index. The Gray test was used to test differences between cumulative incidence rates among the exposure groups. We examined the association of hyperkalemia treatment strategy with recurrent hyperkalemia and cardiovascular events within 1 year by using Fine and Gray subdistribution hazards models accounting for the competing risk of death. We examined the association of hyperkalemia treatment strategy with all-cause mortality within 1 year by using Cox proportional hazards models. Only the first hyperkalemia event was considered. Models were adjusted for demographics (age, sex, income quintile, rural locale, and residence in a long-term care facility), preexisting comorbid illnesses (coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass graft, congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation/flutter, stroke, peripheral vascular disease, venous thromboembolism, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic liver disease, and major cancer; within previous 5 years), baseline eGFR category (<30, 30–60, and >60 ml/min per 1.73 m2), baseline serum potassium, medication use (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, β-blockers, statins, and antiplatelet agents; within previous 120 days), and health service utilization (number of hospitalizations and emergency room visits and any nephrology or cardiology visits; within previous 1 year). The no intervention group was treated as the reference group. We conducted all analyses with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). The 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) that did not overlap with one and P values of 0.05 (two sided) were treated as statistically significant.

Additional Analyses

Additional analyses included (1) redefining hyperkalemia as a serum potassium ≥5.8 mEq/L to examine more severe cases of hyperkalemia and (2) censoring at intervention discontinuation. For the latter analysis, individuals in the RAASi discontinuation group were censored upon restart of an RAASi. For all other interventions, patients were censored if there were no refills of the intervention medication within the time period of the prescription period plus an additional 50% of time.

Results

Characteristics of Study Cohort by Hyperkalemia Treatment Strategy

A total of 49,571 patients ≥66 years of age who were treated with an RAASi and had an outpatient hyperkalemia measurement (serum potassium ≥5.3 mEq/L) were included in the analyses (Figure 1). Among this population, 38,254 (77%) received no identified pharmacologic intervention, whereas 11,317 (23%) received a pharmacologic intervention. Of those receiving a pharmacologic intervention, 8417 (74%) underwent RAASi discontinuation, 1675 (15%) underwent RAASi dose decrease, 308 (3%) were newly prescribed a diuretic, 748 (7%) were prescribed an increased dose of a preexisting diuretic, and 169 (1%) were prescribed SPS as treatment for hyperkalemia. Age and sex were similar across the groups (Table 1). The median (interquartile range [IQR]) index potassium value was higher for patients prescribed SPS (5.7 mEq/L [5.5–6.0 mEq/L]) compared with the other groups (no intervention: 5.4 mEq/L [IQR, 5.3–5.6 mEq/L]; RAASi discontinuation: 5.4 mEq/L [IQR, 5.3–5.6 mEq/L]; RAASi dose decrease: 5.5 mEq/L [5.3–5.6 mEq/L]; new diuretic: 5.4 mEq/L [IQR, 5.3–5.6 mEq/L]; and diuretic dose increase: 5.4 mEq/L [IQR, 5.3–5.6 mEq/L]). Patients treated with a diuretic dose increase were more likely to have congestive heart failure and be seen by a cardiologist. Patients treated with SPS had more advanced kidney disease and were more likely to be seen by a nephrologist.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Ontario residents ≥66 years of age treated with a renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitor noted to have at least one outpatient serum potassium ≥5.3 mEq/L between January 1, 2007 and December 31, 2016

| Characteristic | No Intervention | Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System Inhibitor Discontinuation | Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System Inhibitor Dose Decrease | New Diuretic Prescription | Diuretic Dose Increase | New Sodium Polystyrene Sulfonate Prescription |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total, N | 38,254 | 8417 | 1675 | 308 | 748 | 169 |

| Age, mean (SD), yr | 79 (8) | 77 (7) | 79 (8) | 77 (7) | 80 (8) | 79 (8) |

| Women, N (%) | 20,612 (54) | 3909 (46) | 839 (50) | 153 (50) | 395 (53) | 85 (50) |

| Income quintile, N (%) | ||||||

| Quintile 1 | 8795 (23) | 1671 (20) | 366 (22) | 79 (26) | 167 (22) | 41 (24) |

| Quintile 2 | 8464 (22) | 1866 (22) | 349 (21) | 74 (24) | 180 (24) | 37 (22) |

| Quintile 3 | 7636 (20) | 1744 (21) | 354 (21) | 53 (17) | 137 (18) | 30 (18) |

| Quintile 4 | 6940 (18) | 1606 (19) | 292 (17) | 46 (15) | 145 (19) | 33 (20) |

| Quintile 5 | 6275 (16) | 1513 (18) | 312 (19) | 54 (18) | 114 (15) | 28 (17) |

| Rural, N (%) | 4281 (11) | 1019 (12) | 218 (13) | 30 (10) | 86 (11) | 24 (14) |

| Long-term care resident, N (%) | 4765 (12) | 229 (3) | 193 (12) | ≤5a | 127 (17) | 16 (9) |

| eGFR, mean (SD), ml/min per 1.73 m2b | 56 (20) | 57 (21) | 53 (20) | 58 (20) | 51 (20) | 40 (19) |

| eGFR category, ml/min per 1.73 m2, N (%)b | ||||||

| >60 | 16,209 (42) | 3791 (45) | 599 (36) | 137 (44) | 225 (30) | 23 (14) |

| 30–60 | 18,133 (47) | 3713 (44) | 861 (51) | 142 (46) | 409 (55) | 86 (51) |

| <30 | 3912 (10) | 913 (11) | 215 (13) | 29 (9) | 114 (15) | 60 (36) |

| Serum potassium, mean (SD), mEq/L | 5.5 (0.2) | 5.5 (0.3) | 5.5 (0.3) | 5.5 (0.2) | 5.5 (0.3) | 5.8 (0.4) |

| Comorbidities, N (%)c | ||||||

| Coronary artery disease | 18,599 (49) | 3977 (47) | 935 (56) | 144 (47) | 449 (60) | 76 (45) |

| Myocardial infarction | 3041 (8) | 555 (7) | 158 (9) | 11 (4) | 82 (11) | 22 (13) |

| Coronary artery bypass graft | 1154 (3) | 296 (4) | 67 (4) | 6 (2) | 41 (5) | ≤5a |

| Congestive heart failure | 10,907 (29) | 1961 (23) | 747 (45) | 50 (16) | 442 (59) | 66 (39) |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 4969 (13) | 920 (11) | 344 (21) | 24 (8) | 212 (28) | 26 (15) |

| Stroke | 1939 (5) | 299 (4) | 92 (5) | 6 (2) | 46 (6) | ≤5a |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1042 (3) | 229 (3) | 57 (3) | 7 (2) | 30 (4) | 6 (4) |

| Venous thromboembolism | 17,321 (45) | 3827 (45) | 853 (51) | 129 (42) | 463 (62) | 88 (52) |

| Hypertension | 32,298 (84) | 7241 (86) | 1444 (86) | 272 (88) | 667 (89) | 138 (82) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 23,313 (61) | 4877 (58) | 1011 (60) | 171 (56) | 434 (58) | 113 (67) |

| Chronic liver disease | 1746 (5) | 498 (6) | 120 (7) | 12 (4) | 46 (6) | 13 (8) |

| Major cancer | 1431 (4) | 416 (5) | 62 (4) | 16 (5) | 28 (4) | 6 (4) |

| Medications, N (%)d | ||||||

| NSAID | 4982 (13) | 1087 (13) | 189 (11) | 43 (14) | 80 (11) | 12 (7) |

| β-blocker | 18,212 (48) | 3476 (41) | 929 (55) | 132 (43) | 462 (62) | 99 (59) |

| Statin | 26,660 (70) | 5334 (63) | 1144 (68) | 220 (71) | 501 (67) | 121 (72) |

| Antiplatelet agent, non-OTC | 1795 (5) | 327 (4) | 66 (4) | 14 (5) | 28 (4) | 12 (7) |

| Health services within past year | ||||||

| Hospitalizations, mean (SD) | 0.4 (0.8) | 0.4 (0.8) | 0.6 (1.0) | 0.3 (0.6) | 0.8 (1.2) | 0.6 (1.1) |

| Emergency room visits, mean (SD) | 1.1 (1.9) | 1.1 (1.7) | 1.3 (1.8) | 0.9 (1.5) | 1.9 (2.7) | 1.3 (1.8) |

| Nephrologist, N (%) | 6325 (17) | 1612 (19) | 335 (20) | 61 (20) | 158 (21) | 86 (51) |

| Cardiologist, N (%) | 20,757 (54) | 4826 (57) | 1079 (64) | 167 (54) | 522 (70) | 92 (54) |

NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; OTC, over the counter.

In accordance with the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences privacy policies, cell sizes less than or equal to five cannot be reported.

eGFR was defined at baseline as the average of the pair of eGFR values closest to index date that were separated by at least 90 days.

Comorbidities were ascertained in the 5 years prior to cohort entry.

Medication use was ascertained in the 120 days prior to cohort entry.

Association of Hyperkalemia Treatment Strategies and 1-Year Risk of Recurrent Hyperkalemia

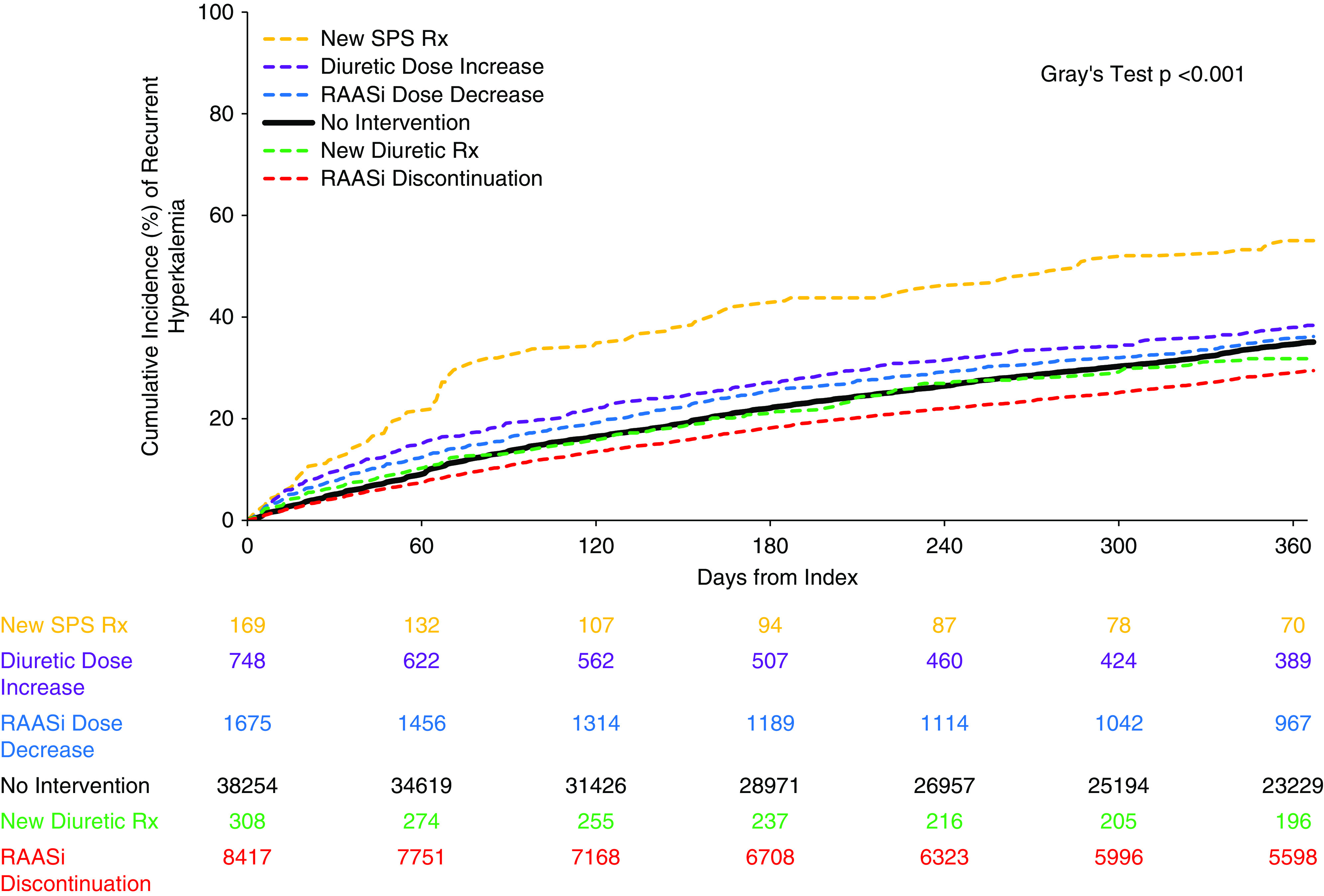

Among the 49,571 patients in the cohort, 16,977 (34%) developed recurrent hyperkalemia within 1 year. Among the treatment strategies, the highest risk of hyperkalemia recurrence was associated with SPS use, and the lowest risk was associated with RAASi discontinuation (hyperkalemia recurrence risk: SPS [55%; 93 of 169], diuretic increase [38%; 287 of 748], RAASi decrease [36%; 606 of 1675], no intervention [35%; 13,413 of 38,254], new diuretic [32%; 98 of 308], and RAASi discontinuation [29%; 2480 of 8417]). This was consistent when we examined the cumulative incidence (Gray test P value <0.001) (Figure 2) and in unadjusted and multivariable-adjusted models (Table 2). Compared with no intervention (referent), the multivariable-adjusted risk for recurrent hyperkalemia was lower with RAASi discontinuation (hazard ratio [HR], 0.82; 95% CI, 0.78 to 0.85), whereas there was no difference in risk with RAASi decrease (HR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.86 to 1.02), new diuretic (HR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.78 to 1.17), or diuretic increase (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.87 to 1.12) and a higher risk with SPS (HR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.04 to 1.63).

Figure 2.

One-year cumulative incidence of recurrent hyperkalemia. Hyperkalemia was defined as a serum potassium ≥5.3 mEq/L. The order of the intervention groups is listed from highest to lowest in regard to cumulative incidence of recurrent hyperkalemia over the 1-year follow-up period. The numbers listed in the table represent the number of patients in each group remaining at risk in each intervention group at 60-day intervals throughout the 1-year follow-up period.

Table 2.

Recurrent hyperkalemia, cardiovascular events, and all-cause mortality within 1 year by outpatient hyperkalemia intervention

| Intervention | Recurrent Hyperkalemia | Cardiovascular Events | All-Cause Mortality | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Events (%) | Unadjusted Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | Adjusted Hazard Ratioa (95% Confidence Interval) | No. of Events (%) | Unadjusted Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | Adjusted Hazard Ratioa (95% Confidence Interval) | No. of Events (%) | Unadjusted Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | Adjusted Hazard Ratioa (95% Confidence Interval) | |

| No intervention, n=38,254 | 13,413 (35) | Reference | Reference | 8041 (21) | Reference | Reference | 3339 (9) | Reference | Reference |

| RAASi discontinuation, n=8417 | 2480 (29) | 0.81 (0.77 to 0.84) | 0.82 (0.78 to 0.85) | 1573 (19) | 0.88 (0.83 to 0.93) | 0.96 (0.91 to 1.02) | 604 (7) | 0.80 (0.74 to 0.87) | 1.05 (0.96 to 1.15) |

| RAASi dose decrease, n=1675 | 606 (36) | 1.06 (0.98 to 1.16) | 0.94 (0.86 to 1.02) | 582 (35) | 1.87 (1.71 to 2.03) | 1.35 (1.23 to 1.48) | 198 (12) | 1.36 (1.18 to 1.57) | 1.15 (1.00 to 1.33) |

| New diuretic Rx, n=308 | 98 (32) | 0.90 (0.74 to 1.11) | 0.95 (0.78 to 1.17) | 53 (17) | 0.81 (0.62 to 1.06) | 1.00 (0.74 to 1.34) | 22 (7) | 0.81 (0.53 to 1.23) | 1.23 (0.80 to 1.89) |

| Diuretic dose increase, n=748 | 287 (38) | 1.16 (1.03 to 1.31) | 0.99 (0.87 to 1.12) | 367 (49) | 3.00 (2.69 to 3.34) | 1.70 (1.51 to 1.91) | 133 (18) | 2.11 (1.77 to 2.51) | 1.36 (1.14 to 1.62) |

| New SPS Rx, n=169 | 93 (55) | 1.96 (1.58 to 2.43) | 1.30 (1.04 to 1.63) | 56 (33) | 1.74 (1.33 to 2.27) | 1.29 (0.98 to 1.69) | 19 (11) | 1.28 (0.82 to 2.00) | 0.97 (0.62 to 1.53) |

Hyperkalemia was defined as a serum potassium ≥5.3 mEq/L. RAASi, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitor; Rx, prescription; SPS, sodium polystyrene sulfonate.

Models are adjusted for demographics (age, sex, income quintile, rural locale, and residence in a long-term care facility), preexisting comorbid illnesses (coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass graft, congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation/flutter, stroke, peripheral vascular disease, venous thromboembolism, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic liver disease, and major cancer; within previous 5 years), baseline eGFR category (<30, 30–60, and >60 ml/min per 1.73 m2), baseline serum potassium, medication use (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, β-blockers, statins, and antiplatelet agents; within previous 120 days), and health service utilization (number of hospitalizations and emergency room visits and any nephrology or cardiology visits; within previous 1 year).

Association of Hyperkalemia Treatment Strategies with 1-Year Cardiovascular Event and All-Cause Mortality Rates

With no intervention as the reference group, RAASi dose decrease and diuretic dose increase were associated with a higher risk for cardiovascular events over 1 year in multivariable-adjusted models (HR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.23 to 1.48 and HR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.51 to 1.91, respectively) (Table 2). When compared with no intervention, there was no significant difference in risk for cardiovascular events over 1 year in the RAASi discontinuation (HR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.91 to 1.02), new diuretic (HR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.74 to 1.34), and SPS groups (HR, 1.29; 95% CI, 0.98 to 1.69).

With no intervention as the reference group, diuretic dose increase was associated with a higher 1-year all-cause mortality risk in multivariable-adjusted models (HR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.14 to 1.62) (Table 2). When compared with no intervention, there was no significant difference in 1-year all-cause mortality risk in the RAASi discontinuation (HR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.96 to 1.15), RAASi dose decrease (HR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.00 to 1.33), new diuretic (HR, 1.23; 95% CI, 0.80 to 1.89), and SPS groups (HR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.62 to 1.53).

Additional Analyses

Our findings were similar when examining a higher threshold for hyperkalemia (serum potassium ≥5.8 mEq/L) (Supplemental Figure 1, Supplemental Table 4) and in models incorporating censoring upon intervention discontinuation (Supplemental Tables 5 and 6).

Discussion

In this large population-based cohort study of patients ≥66 years of age with RAASi-associated hyperkalemia, we found that RAASi discontinuation was the pharmacologic intervention associated with the lowest risk for recurrent hyperkalemia over 1 year compared with other common hyperkalemia interventions. These results were consistent in patients with a higher degree of hyperkalemia and when we censored upon intervention discontinuation. RAASi discontinuation did not appear to be associated with a higher short-term (1-year) risk of adverse cardiovascular events or all-cause mortality.

Population-based studies have demonstrated that hyperkalemia is a common and recurring problem for patients prescribed RAASi medications. In a large nationwide study in Sweden, Nilsson et al. (12) showed that angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists increased the odds for hyperkalemia by 57%, 22%, and 44%, respectively. Adelborg et al. (19) showed that among Danish individuals newly prescribed RAASi medications, 16% had a hyperkalemia event in a median time of 2.2 years. Among this population, the risk for RAASi-associated hyperkalemia was further amplified among patients with CKD, diabetes mellitus, and congestive heart failure—conditions for which evidence-based guidelines suggest use of these medications. Of the patients who developed RAASi-associated hyperkalemia, 37% developed recurrent hyperkalemia within 6 months—a recurrence rate similar to that observed in our cohort (34%).

Currently, there is no consensus on the optimal approach to the outpatient management of RAASi-related hyperkalemia. In fact, wide heterogeneity exists among providers about which intervention to use. Our study shows that the most common intervention (among those included in our study) was RAASi discontinuation; however, a substantial number of patients are treated with other interventions, including RAASi dose decrease, new or increased diuretic prescription, or SPS prescription. These finding are consistent with the results of a large United States–based cohort study by Chang et al. (6) that also showed RAASi discontinuation to be the most common outpatient treatment for hyperkalemia, although a number of other interventions are commonly used.

Our findings further add to the existing literature on outpatient hyperkalemia management that RAASi discontinuation is associated with the lowest 1-year rate of recurrent hyperkalemia. However, providers must factor individual patient scenarios into the decision on which intervention to use. RAASis are mainstays of treatment for patients with CKD (in particular, proteinuric CKD), diabetes mellitus (with associated hypertension and/or albuminuria), and congestive heart failure (in particular when the ejection fraction is low) as they slow progression of kidney disease and attenuate adverse cardiac remodeling (20,21). Therefore, prior to discontinuation of RAASi medications, providers must carefully balance the benefit of preventing recurrent hyperkalemia (and its associated morbidity and mortality) against potentially expedited kidney and cardiac disease progression on a case-by-case basis. Nevertheless, these population-based findings suggest that RAASi discontinuation associates with reduced hyperkalemia, with no short-term (1-year) increase in cardiovascular events or mortality.

The link between hyperkalemia and cardiovascular events is well established. Most studies on the relationship between hyperkalemia and cardiovascular events have been performed in the inpatient setting (22,23). However, a study by Hughes-Austin et al. (24) pooled two large observational cohorts, the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis and the Cardiovascular Health study, to show that outpatient hyperkalemia was associated with both cardiovascular events and mortality. Interestingly, they found the strongest association between outpatient hyperkalemia and cardiovascular events and mortality among diuretic users, consistent with our results (24).

Our results must be interpreted within the context of the study design. First, this study is observational; therefore, we were able to identify association but not causation between the study interventions and outcome measures. However, our analytic models adjusted for numerous potential confounding variables, which should reduce observed confounding, although we acknowledge that unobserved confounding may still occur. Further, we performed analyses using two definitions of hyperkalemia of varying severity with consistent results. Second, our outcome measures were limited to 1 year. This time frame was selected to limit crossover between exposure groups. However, this restriction also limited our ability to determine associations between outpatient interventions for RAASi-associated hyperkalemia and long-term outcomes, which may differ from the short-term outcomes found in this study. Perhaps the long-term effects of RAASi discontinuation on conditions such as proteinuric CKD and congestive heart failure, where RAASis are known to slow disease progression, may take a longer period of time to fully manifest. Third, as our study was focused on ambulatory hyperkalemia interventions, we attempted to exclude patients who were acutely ill or suffered AKI around the hyperkalemia episode by excluding those who died or were hospitalized within 30 days of the initial hyperkalemia measurement. This excluded a large number of patients from the study and could have introduced some degree of bias to our results. Fourth, newer potassium-binding agents, such as patiromer (25) and zirconium cylosilicate (26), were not included as they were not widely available in Ontario during the time frame of our study. These agents provide an alternative method to manage outpatient hyperkalemia. Fifth, as this study was designed using administrative data, which enabled us to capture a large sample size, it also restricted our ability to capture certain data. Only interventions that generated new prescriptions were captured, whereas shorter-term hyperkalemia interventions, which sometimes do not generate a new prescription, would not have been captured. For instance, if a provider gave a verbal order to hold or reduce the RAASi or to increase the dose of a diuretic to treat hyperkalemia without generating a new prescription, this would not be captured within our data sources. This could lead to these patients being misclassified into the reference “no intervention” group, which could bias the results toward the null. Additionally, we were not able to determine whether diuretics were prescribed for hyperkalemia or other comorbidities, and the diuretic dose increase group did have higher rates of congestive heart failure. Adherence is also not captured, which may explain the higher risk for recurrent hyperkalemia seen with SPS, adherence with which is known to be poor due to gastrointestinal side effects (27,28). Although the diagnosis of hypertension is available through our data sources and was adjusted for within our analyses, actual BP measurement data are not. BP control could have potentially influenced providers on selecting one intervention (e.g., diuretics) versus another. Further, our data sources were unable to reliably distinguish whether congestive heart failure was associated with preserved versus reduced ejection fraction, the latter of which has a more well-established indication for RAASi therapy. Finally, our inclusion and exclusion criteria reduced the population size that we were able to study, which may limit the generalizability of our findings.

In conclusion, among older patients with RAASi-related hyperkalemia, RAASi discontinuation is the pharmacologic intervention associated with the lowest risk for recurrent hyperkalemia and does not associate with a higher 1-year risk of cardiovascular events or death. Prospective studies are necessary to confirm the short- and long-term implications of the various options for treating RAASi-related hyperkalemia.

Disclosures

G.L. Hundemer reports employment with the Ottawa Hospital and serving on the editorial board of Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease. G.A. Knoll reports employment with the Ottawa Hospital and serving on the editorial board of Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease. S.J. Leon reports employment with the Chronic Disease Innovation Centre and the University of Manitoba. E. Rhodes reports employment with Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. M.M. Sood reports employment with Ottawa Hospital; receiving honoraria from AstraZeneca; serving on the editorial boards of American Journal of Kidney Disease, Canadian Journal of Cardiology, and CJASN; and serving as an editor of Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease and a member of the American Society of Nephrology Highlights ESRD Team. R. Talarico reports employment with Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. N. Tangri reports consultancy agreements with Mesentech Inc., PulseData Inc., Renibus, and Tricida Inc.; ownership interest in Clinpredict Ltd., Mesentech Inc., PulseData Inc., Renibus, and Tricida Inc.; receiving research funding from AstraZeneca Inc., Janssen, Otsuka, and Tricida Inc.; receiving honoraria from AstraZeneca Inc., Bayer, BI-Lilly, Janssen, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, and Pfizer; and serving as a scientific advisor or member of Mesentech, Pulsedata Inc., Renibus, and Tricida Inc. The remaining author has nothing to disclose.

Funding

G.L. Hundemer is supported by Kidney Research Scientist Core Education and National Training Program New Investigator award 2019KP-NIA626990. M.M. Sood is supported by the Jindal Research Chair for the Prevention of Kidney Disease. This study was supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Core funding for ICES Ottawa is provided by University of Ottawa, the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Core funding for ICES Western is provided by the Academic Medical Organization of Southwestern Ontario, the Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, Western University, and the Lawson Health Research Institute.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank IMS Brogan Inc. for use of their Drug Information Database.

This study was completed by the ICES Western and Ottawa sites. The research was conducted by members of the ICES Kidney, Dialysis and Transplantation team. Parts of this material are on the basis of data and/or information compiled and provided by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) and Service Ontario. Parts of this material are on the basis of data and/or information compiled and provided by CIHI.

The analyses, conclusions, opinions, and statements expressed in the material are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the funding or data sources; no endorsement is intended or should be inferred. The analyses, conclusions, opinions, and statements expressed in the material are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of CIHI. The funders of this study had no role in study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data,; writing the report; or the decision to submit the report for publication.

G.L. Hundemer, M.M. Sood, and R. Talarico were responsible for study concept and design; R. Talarico was responsible for statistical analysis; G.L. Hundemer, M.M. Sood, and R. Talarico were responsible for acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; G.L. Hundemer and M.M. Sood drafted the manuscript; all authors provided critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; E. Rhodes provided administrative, technical, and material support; M.M. Sood provided supervision; and all authors contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and agree to be personally accountable for the individual’s own contributions and to ensure that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work, even one in which the author was not directly involved, are appropriately investigated and resolved, including with documentation in the literature if appropriate.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Recurrent Hyperkalemia in Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System Inhibitor (RAASi) Treatment: Stuck between a Rock and a Hard Place,” on pages 345–347.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.12990820/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Table 1. Reporting of Studies Conducted Using Observational Routinely-Collected Health Data statement checklist.

Supplemental Table 2. Databases and code definitions for inclusion, exclusions, and outcomes.

Supplemental Table 3. List of drug names used to define renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitor and diuretic exposure groups.

Supplemental Table 4. Recurrent hyperkalemia, cardiovascular events, and all-cause mortality within 1 year by outpatient hyperkalemia intervention (hyperkalemia definition K+ ≥5.8 mEq/L).

Supplemental Table 5. Recurrent hyperkalemia, cardiovascular events, and all-cause mortality within 1 year by outpatient hyperkalemia intervention (hyperkalemia definition K+ ≥5.3 mEq/L), including censoring at intervention discontinuation.

Supplemental Table 6. Recurrent hyperkalemia, cardiovascular events, and all-cause mortality within 1 year by outpatient hyperkalemia intervention (hyperkalemia definition K+ ≥5.8 mEq/L), including censoring at intervention discontinuation.

Supplemental Figure 1. One-year cumulative incidence of recurrent hyperkalemia (serum potassium ≥5.8 mEq/L).

References

- 1.Montford JR, Linas S: How dangerous is hyperkalemia? J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 3155–3165, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bashour T, Hsu I, Gorfinkel HJ, Wickramesekaran R, Rios JC: Atrioventricular and intraventricular conduction in hyperkalemia. Am J Cardiol 35: 199–203, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Einhorn LM, Zhan M, Hsu VD, Walker LD, Moen MF, Seliger SL, Weir MR, Fink JC: The frequency of hyperkalemia and its significance in chronic kidney disease. Arch Intern Med 169: 1156–1162, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finch CA, Sawyer CG, Flynn JM: Clinical syndrome of potassium intoxication. Am J Med 1: 337–352, 1946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luo J, Brunelli SM, Jensen DE, Yang A: Association between serum potassium and outcomes in patients with reduced kidney function. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 90–100, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang AR, Sang Y, Leddy J, Yahya T, Kirchner HL, Inker LA, Matsushita K, Ballew SH, Coresh J, Grams ME: Antihypertensive medications and the prevalence of hyperkalemia in a large health system. Hypertension 67: 1181–1188, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bandak G, Sang Y, Gasparini A, Chang AR, Ballew SH, Evans M, Arnlov J, Lund LH, Inker LA, Coresh J, Carrero JJ, Grams ME: Hyperkalemia after initiating renin-angiotensin system blockade: The Stockholm Creatinine Measurements (SCREAM) project. J Am Heart Assoc 6: e005428, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reardon LC, Macpherson DS: Hyperkalemia in outpatients using angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. How much should we worry? Arch Intern Med 158: 26–32, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sarafidis PA, Blacklock R, Wood E, Rumjon A, Simmonds S, Fletcher-Rogers J, Ariyanayagam R, Al-Yassin A, Sharpe C, Vinen K: Prevalence and factors associated with hyperkalemia in predialysis patients followed in a low-clearance clinic. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 1234–1241, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarwar CM, Papadimitriou L, Pitt B, Piña I, Zannad F, Anker SD, Gheorghiade M, Butler J: Hyperkalemia in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 68: 1575–1589, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pitt B, Zannad F, Remme WJ, Cody R, Castaigne A, Perez A, Palensky J, Wittes J; Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study Investigators: The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. N Engl J Med 341: 709–717, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nilsson E, Gasparini A, Ärnlöv J, Xu H, Henriksson KM, Coresh J, Grams ME, Carrero JJ: Incidence and determinants of hyperkalemia and hypokalemia in a large healthcare system. Int J Cardiol 245: 277–284, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sterns RH, Grieff M, Bernstein PL: Treatment of hyperkalemia: Something old, something new. Kidney Int 89: 546–554, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Statistics Canada : Table 17-10-0005-01. Population estimates on July 1st, by age and sex. 2020. Available at https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1710000501. Accessed December 20, 2020.

- 15.Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, Harron K, Moher D, Petersen I, Sørensen HT, von Elm E, Langan SM; RECORD Working Committee: The REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med 12: e1001885, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levy AR, O’Brien BJ, Sellors C, Grootendorst P, Willison D: Coding accuracy of administrative drug claims in the Ontario Drug Benefit database. Can J Clin Pharmacol 10: 67–71, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Statistics Canada : Table 17-10-0022-01. Estimates of interprovincial migrants by province or territory of origin and destination, annual. 2020. Available at https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1710002201. Accessed December 18, 2020.

- 18.Suissa S: Immortal time bias in pharmaco-epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol 167: 492–499, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adelborg K, Nicolaisen SK, Hasvold P, Palaka E, Pedersen L, Thomsen RW: Predictors for repeated hyperkalemia and potassium trajectories in high-risk patients - A population-based cohort study. PLoS One 14: e0218739, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mann DL, Barger PM, Burkhoff D: Myocardial recovery and the failing heart: Myth, magic, or molecular target? J Am Coll Cardiol 60: 2465–2472, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarafidis PA, Khosla N, Bakris GL: Antihypertensive therapy in the presence of proteinuria. Am J Kidney Dis 49: 12–26, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.An JN, Lee JP, Jeon HJ, Kim DH, Oh YK, Kim YS, Lim CS: Severe hyperkalemia requiring hospitalization: Predictors of mortality. Crit Care 16: R225, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Phillips BM, Milner S, Zouwail S, Roberts G, Cowan M, Riley SG, Phillips AO: Severe hyperkalaemia: Demographics and outcome. Clin Kidney J 7: 127–133, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hughes-Austin JM, Rifkin DE, Beben T, Katz R, Sarnak MJ, Deo R, Hoofnagle AN, Homma S, Siscovick DS, Sotoodehnia N, Psaty BM, de Boer IH, Kestenbaum B, Shlipak MG, Ix JH: The relation of serum potassium concentration with cardiovascular events and mortality in community-living individuals. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 245–252, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weir MR, Bakris GL, Bushinsky DA, Mayo MR, Garza D, Stasiv Y, Wittes J, Christ-Schmidt H, Berman L, Pitt B; OPAL-HK Investigators: Patiromer in patients with kidney disease and hyperkalemia receiving RAAS inhibitors. N Engl J Med 372: 211–221, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Packham DK, Rasmussen HS, Lavin PT, El-Shahawy MA, Roger SD, Block G, Qunibi W, Pergola P, Singh B: Sodium zirconium cyclosilicate in hyperkalemia. N Engl J Med 372: 222–231, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harel Z, Harel S, Shah PS, Wald R, Perl J, Bell CM: Gastrointestinal adverse events with sodium polystyrene sulfonate (Kayexalate) use: A systematic review. Am J Med 126: 264.e9–264.e24, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noel JA, Bota SE, Petrcich W, Garg AX, Carrero JJ, Harel Z, Tangri N, Clark EG, Komenda P, Sood MM: Risk of hospitalization for serious adverse gastrointestinal events associated with sodium polystyrene sulfonate use in patients of advanced age. JAMA Intern Med 179: 1025–1033, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.