“All break through, no follow through” – S Woolf Washington Post editorial 2006 on the need to close the gaps in the US health care delivery system (1)

What is implementation science?

The gap between care that is effective and care that is delivered reflects, in large measure, the paucity of evidence about implementation (2). Implementation science is the systematic study of how to design and evaluate a set of activities to facilitate successful uptake of an evidence-based health intervention. ‘Evidence-based’ refers to interventions that have undergone sufficient scientific evaluation to be considered effective and/or are recommended by respected public health or professional organizations. As noted by Madon et al, “Scientists have been slow to view implementation as a dynamic, adaptive, multi-scale phenomenon that can be addressed through a research agenda” (3). But the tide is changing, with funding agencies increasingly recognizing the need to support research to guide implementation. Implementation science seeks to understand factors that determine why an evidence-based intervention may or may not be adopted within specific healthcare or public health settings, and uses this information to develop and test strategies to improve the speed, quantity and quality of uptake (4). Other terms – such as knowledge translation – are also used to describe research to understand factors important to evidence uptake. The journal Implementation Science defines implementation research as “the scientific study of methods to promote the systematic uptake of proven clinical treatments, practices, organizational, and management interventions into routine practice, and hence to improve health. In this context, it includes the study of influences on patient, healthcare professional, and organizational behavior in either healthcare or population settings.” (http://www.implementationscience.com/about).

In the field of Emergency Medicine, as indicated by the scoping review by Tavender and colleagues (5), a growing number of studies characterize evidence-practice gaps in areas such as head trauma, management of sepsis, and acute pulmonary care, primarily asthma. However, few studies to date have identified barriers and facilitators to implementation of evidence-based practice which use behavioral theory to guide development of implementation strategies, or employ rigorous evaluation designs to determine whether–and importantly, why– strategies to reverse the gap are effective – the cornerstones of implementation science. A key reason for the persistent gaps between evidence and practice across all areas of medicine is that there have been few attempts to identify or target factors critical for successful implementation of an evidence-based intervention. There is either no explicit implementation strategy or the strategy is based on a best guess rather than on a systematic assessment of crucial barriers and enablers. A different approach is needed to close the evidence-practice gap and thereby achieve the triple aim of improved health, improved patient experience, and reduced health care costs. Uptake of evidence-based practices in emergency medicine, as well as many other disciplines in medicine, calls for an increased focus on implementation science research.

What are the key aspects of implementation science?

Although it is a relatively new field, implementation science explicitly focuses on mechanisms of change in order to understand and improve the process of implementation. We believe that research to close the evidence-practice gap should be guided by the following three key principles:

1) Behavior change is inherent to the translation of evidence into practice, policy, and public health improvements. In order to effectively engage in implementation science research, it is necessary to understand the role of behavior change in developing and evaluating an implementation strategy. In most situations, an evidence-practice gap exists because individuals or organizations are not doing something that is recommended. Strategies that encourage providers to follow clinical practice guidelines, patients to improve medication adherence, or communities to increase uptake of screening programs can all be considered “behavior change interventions”, as they are designated, coordinated activities intended to change specific behaviors. Behavioral theory is therefore helpful to understand the determinants of current behaviors and to design and evaluate targeted implementation strategies to achieve the desired change (6,7).

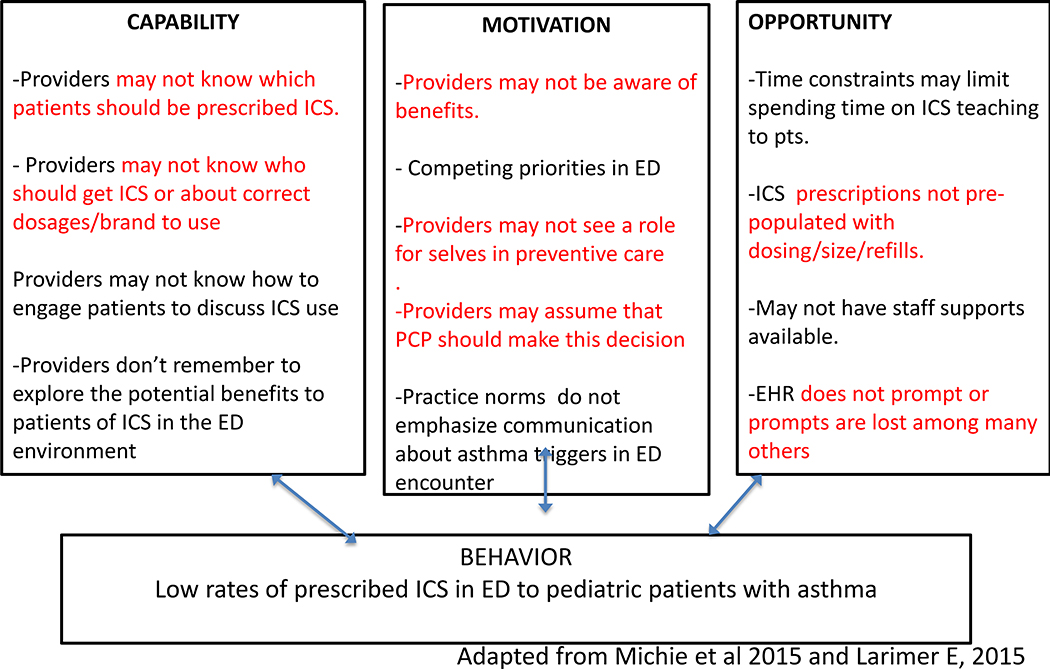

One example of how behavioural theory is used to structure understanding of barriers and develop implementation strategies is the COM-B model and the related Behavior Change Wheel (BCW) (6). The COM-B model specifies that changing the occurrence of any behavior requires changing Capability, Opportunity and/ or Motivation. ‘Capability’ refers to the ability to engage in the thoughts or physical processes necessary for the behavior, ‘Opportunity’ relates to factors in the environment or social setting that influence behavior, and ‘Motivation’ is the conscious beliefs as well as unconsciously based emotions/impulses, that direct behavior (6). Thus the Com-B model can be used to “diagnose” why the desired behavior is not occurring. Once a behavior is understood in terms of these three domains, the BCW can be used to identify functions that an effective intervention could deliver to overcome barriers or enhance enablers within each domain (for example, functions such as education or training to increase ‘Capability’). The BCW goes on to identify evidence-based behavior change techniques that can be used to enact different intervention functions (for example, counseling or health coaching to deliver education). In doing so, the BCW provides a common language to understand, describe, and target behavior change across different contexts and health problems. Implementation Science approaches such as the COM-B diagnosis make explicit the thinking about behavioral barriers to an evidence-practice gap. This explicitness is thought to help improve the relevance (and therefore effect) of interventions in their specific settings as well as generalizability of behavior change interventions across settings.

2) Engagement with a range of individuals and stakeholder organizations is imperative to achieve effective translation and sustained improvement in implementation outcomes. Historically, many initiatives to promote healthy behaviors and improve the quality of health care delivery have been implemented without direct input from targeted individuals/communities (8,9). In contrast, in community-engaged research, community input is incorporated into the development of the question, execution of the project, analysis of the results and/or dissemination of the findings (10). A fundamental premise of community-engaged research is that community stakeholders have credible, intimate and necessary understandings of the concerns, values, assets and activities of their communities.

The initial steps to starting a community-engaged research project is to identify groups or relationships relevant to your area of research and to make efforts to connect with them to start a conversation about the evidence-practice gaps or health topics you care about and to see if these are important or of interest to them. Stakeholders will vary depending on the research question and can include individuals (patients, providers, community members etc), delivery systems (clinics, hospitals) and others (payers, government agencies, funders, etc) (10). Community-engaged research can occur on a spectrum from “more intensive” to “less intensive.” A “more intensive” degree of community-engaged research would involve stakeholder collaboration in all aspects of the research. A “less intensive” approach to community-engaged research would seek stakeholder input for specific steps of the study. By incorporating stakeholder input and participation in research, the results generated are more likely to be useful and applicable for the intended communities.

3) Implementation science research benefits from flexibility and often non-linear approaches in order to fit within real world situations. In practice, this means that a cyclical, rather than linear, approach and long-term view are necessary. This is because translating evidence into practice requires attention to real-world settings in which many contextual variables will influence the implementation process and require re-visiting earlier steps in the process. For example, new barriers can become apparent over time or reflect changes in the environment, such as the addition of new guidelines or technologies, that impact the processes involved in the behavior. (11).

What steps are involved in implementation science research?

In this section we describe a step-wise approach to conducting implementation science research across three phases: 1) pre-implementation planning (engaging stakeholders and making the case for evidence translation), 2) implementation strategy design (using behavioral theory/frameworks to identify barriers and facilitators to implementation and guide development of implementation strategies) and 3) implementation strategy evaluation (employing rigorous evaluation designs to determine whether strategies to reverse the gap are effective and why or why not) (Table 1). We describe the activities involved in each phase, and provide an example related to the prescription of controller medications to children presenting to the emergency department with an asthma exacerbation that links these activities with the three principles outlined above.

Table 1.

Steps for Conducting Implementation Science and Pre-Intervention Planning Research

|

I. PRE-INTERVENTION PLANNING STEPS |

| 1. Describe the evidence to be translated and its relation to a health problem. Steps 1 and 2 can occur concurrently |

| a. What evidence (health related behavior, test, procedure, treatment, intervention, program) will be translated? |

| b. Justify the evidence is ready to be translated (including in the local context) |

| c. What health problem will translation of the evidence improve? Justify selection of this health problem as a priority in the setting you plan to work. |

|

2. Identify stakeholder communities and conduct outreach to work with them. (if not completed in step 1) |

| a. List key communities/stakeholders involved in translating your evidence |

| b. Consider vested interests of key communities/stakeholders |

| c. Describe plan for engaging communities/stakeholders |

|

3. Describe the Evidence-Practice Gap |

| a. Performance gap. What is the difference between current and ideal practice and behaviors? What are the underlying conditions and context? |

| b. Outcome gap. How much improvement in health outcomes (safety, effectiveness, efficiency, patient-centeredness, timeliness and/or eliminating disparities in care) could be achieved if the performance gap was eliminated? |

| c. Could unintended consequences result from attempts to change practices or conditions contributing to performance gap? |

|

4. Determine the Population, Organization and/or Stakeholder Readiness for Change |

| a. Strategic. Is addressing the problem area part of strategic priorities? |

| b. Structural. Are there local programs or resources that will facilitate implementation and sustain the improvement activity after the project team is done? |

|

II. INTERVENTION DESIGN STEPS |

| 1. Describe evidence-practice gap in behavioral terms (Who needs to do what differently?) |

| 2. Select behaviors upon which to frame the implementation strategy |

| 3. Identify barriers and enablers of selected behaviors using a theoretical framework |

| 4. Select evidence-based strategies for behavior change (using the chosen theory or framework) |

|

III. IMPLEMENTATION STRATEGY EVALUATION STEPS |

| 1. Identify and measure mediators of change |

| NOTE: may repeat some steps above or look at institutional/community behavior change theories and frameworks. |

|

2. Select process, implementation and health outcomes |

| 3. Select appropriate and feasible study designs |

Pre-implementation Planning:

Pre-implementation planning begins with identifying the evidence to be translated (health-related behavior, test, procedure, etc.) and its relation to a health problem. The case for translation is strongest when the effectiveness of the practice change has been clearly demonstrated in clinical trials and/or the practice is recommended by professional societies or other professional organizations. To make the case for translation, it is helpful to describe the evidence-practice gap in terms of performance and outcome gaps.

The performance gap is the difference between current and ideal practice/behavior, ideally in the setting in which the research is taking place. An example of how the theory-based behavioral components of the COM-B model might be used is found in Figure 1 depicting the problem of provision of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) by ED physicians to pediatric patients with persistent asthma. In this figure, examples of capability, motivation, and opportunity-related barriers and enablers are shown.Existing literature and internal data sources can be used to identify the evidence-practice gap, (e.g. pediatric ED providers do not prescribe inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) for patients being seen for asthma exacerbations despite evidence-based recommendations and guidelines) and create an initial version of the COM-B model to understand the behavior of non-prescribing of ICS in context For example, a well-known motivational barrier identified in the literature may be that there are well-known competing demands in the hectic ED environment, making it difficult to add any practice change interventions. Approaches that can be used to complete this COM-B diagnosis for a particular setting include observation, surveys, administrative data reviews, and in-depth interviews, as well as other approaches. In this example, additional barriers that may not have been considered may only be understood from a careful study of the ED physicians behavior in the particular setting of your work. The process of engaging front-line physicians in understanding COM-B related contributors to the problem can be seen as community engagement strategy, and others may also be relevant to the question under investigation..

Figure 1.

Applying COM-B to the provision of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) to pediatric patients with persistent asthma by ED physicians

The outcome gap is determined as the difference between current health outcomes and those that are expected to be achieved with if the recommended practice were observed. In our example this would be that when children with moderate to severe asthma are not prescribed ICS at ED discharge, patient-centered care is compromised; patients have poorly controlled asthma and decreased quality of life, and the likelihood of unscheduled ED visits and their accompanying costs rises. The outcome gap represents the potential improvements in healthcare quality (safety, effectiveness, efficiency, patient-centeredness, and equity) or healthcare costs that could be achieved if the practice variation was reduced. The case for translation can be further strengthened by indicating why the health problem the intervention seeks to improve is a priority in the setting in which the research will take place or to the funder of the evidence translation project.

It undertaking an implementation-focused research endevour it is essential to also identify and engage potential stakeholders across levels (providers, patients, community systems, policy makers) in order to assess readiness for change and whether there is adequate consensus that the evidence is ready to be translated and that the health problem is part of strategic priorities. In this example, it would be essential at the outset to engage the physicians as stakeholder community to improve an understanding of barriers they face to prescribing- for example, to understand what ICS means prescribing to them and if they feel well trained to prescribe. It is also likely that patients and their families as well as ED staff are other important stakeholder community groups, and it could be also important to include pharmacists as stakeholders, to identify any barriers relevant to the nature of the prescription process. Stakeholder engagement can also involve identifying and reaching out to local programs or resources that can be utilized to facilitate implementation and ensure sustainability after the research is completed. It is also important to consider and acknowledge any potential unintended negative consequences that may arise as a result of changing current practice conditions.

Designing the Implementation Strategy:

Implementation science promotes a systematic approach to designing a strategy to facilitate uptake of an evidence based-intervention. The systematic approach includes: 1) Identifying behaviors contributing to the evidence-practice gap; 2) Identifying key determinants of current behavior and the desired behavior change using a theoretical framework and 3) Selecting components of the implementation strategy that target the key determinants (using the chosen theory or framework). Designing an implementation strategy begins with listing the specific behaviors that need to occur to facilitate uptake of an evidence-based intervention, and then selecting one or more target behaviors to focus on. The target behaviors should be specified in as detailed a manner as possible (who needs to do what differently, when, where, how, with whom?) (6, 12). The specification enables assessment of key barriers and enablers of the target behavior(s). This step should be guided by a behavioral theory or framework and frequently involves qualitative research. Last, potential behavior change techniques (including from other fields such as Quality Improvement) can be mapped to key barriers and enablers again using behavior change theory or frameworks. For example, Mitchie et al have identified 93 distinct behavior change techniques and described their usefulness for targeting specific determinants of behavior change. Again at this stage, consultation with local stakeholders is critical to ensure that selected techniques and their delivery are feasible, relevant, and acceptable. When possible, policy or structural changes that can enable behavior change should also be considered.

Following the COM-B diagnosis (Figure 1), the BCW framework can be employed to determine which intervention function(s) might best address the barriers in the context studied. For example, the motivational barrier about competing demands might be addressed in several ways including: restructuring the environment (to free up time to discuss future medication planning for selected asthma encounters and thereby change the perception that there are too many competing demands), persuading physicians that their professional identity includes prevention (to increase a sense of ownership over prevention of asthma), or promoting goal setting about ICS prescribing (to improve confidence in ability to integrate ICSF prescribing into ED practice settings). Once the choice of intervention function is made, the final step in the behavior change focused intervention planning would be to select a delivery strategy, the “behavior change technique.” For example, if the intervention function of persuasion is selected, there could be trained role models who could provide information and serve as credible resources about the importance of the behavior; and physicians could receive feedback on ICS prescribing behavior. If an implementation strategy involved increasing motivation by providing prompts or cues, an electronic medical record could be used to delivery prompts, particularly if this was guided by information in the medical record suggesting ICS for appropriate patients. (On the other hand, rapid proliferation of electronic prompts might render a prompt related to ICS prescription less effective.) Being able to incorporate flexible strategies to deliver intervention content may be important in order to adapt to broader changes in the setting the intervention is planned for.

Evaluating the Implementation Strategy:

The evaluation of an implementation strategy should focus on 1) Process – how components of the strategy were delivered or adapted and the fidelity to intervention components and principles; 2) Mediators of change – whether the components modified targeted barriers or enhanced targeted enablers; and 3) Outcomes – frequently, whether uptake of the evidence-based intervention increased (or decreased if de-implementation is the goal). These forms of evaluation can be summarized as “process evaluation”- how well the intervention is being implemented and “summative evaluation”- whether change occurred as a result of the intervention. Health outcomes can also include those related to the quality of healthcare (safety, effectiveness, efficiency, patient-centeredness, and equity) when feasible, but in general it should already be known that uptake of the evidence-based intervention improves healthcare quality. Evaluation frameworks such as the RE-AIM (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation and Maintenance) framework can be helpful to guide the selection of process and health outcomes evaluated (see www.re-aim.org for examples)(13). In addition to using frameworks in the evaluation process, it can be important to consider pros and cons of experimental vs quasi-experimental designs, and whether or not qualitative research would enhance the ability to fully understand the effects of the implementation, such as how well the persuasion efforts of peer role models reflect trainings or protocols, or what factors may have led to unintended consequences or spillover effects.

In a proposed study above that incorporates the use of persuasion tinto an intervention to increase ICS prescribing to pediatric asthma patients in urban ED settings (as with having trained role models as credible sources), it may be important to examine to measures of reach, in addition to effectiveness. To do this might involve determining to what extent the intervention reached specific population targeted in the ED setting such as younger physicians or women, or those working in smaller vs larger ED. Adoption measures could be important to see if in a study including large numbers of different types of ED settings, if there are some settings where the intervention practices became part of the practice expectations, in contrast to other settings that did not so readily adopt the intervention. This could provide guidance for on-going trainings and reinforcements unique to particular environments.

There are many commonalities between implementation science and both Quality Improvement (QI) and Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E), but there are some important differences as well. According to current implementation science thinking, and shown in the COM-B examples, the behavioral diagnosis and steps to address barriers to critical behaviors that affect the implementation process are central to ImS, whereas in QI and M&E they often are not. Additionally, the goals of QI research are often less focused on creating generalizable knowledge than on addressing the QI problem at hand. Implementation science focuses more on understanding the etiology of gaps between expected results and observed outcomes, in ways that can be relevant beyond a given situation, whereas QI and M&E research may stop once identification and barriers related to performance of specific projects are determined. Despite these differences, many QI and M&E-related research studies are aligned with implementation science principles and these disciplinary distinctions are not always relevant.

Summary

As in other disciplines, there are wide gaps in the uptake of a range of evidence-based interventions in emergency medicine. Studies are now needed that employ theory-based approaches to understand key behavioral determinants and to design, evaluate and adapt targeted implementation strategies that address the targeted behaviors. These studies should be conducted with broad involvement from multiple relevant stakeholders, should engage multiple disciplinary perspectives, and should be facilitated by research designs and selection of outcomes that best enable implementation research questions to be addressed. Moving forward will require increasing knowledge about implementation science among trainees and practitioners as well as sustained efforts to expand the capacity of emergency medicine researchers to address the implementation research questions that merit focused attention.

REFERENCES

- (1).Woolfe S TRIALS & ERRORS Unhealthy Medicine Sunday, January 8, 2006- By Woolf Steven H. Available at http://www.fic.nih.gov/News/Events/implementation-science/Pages/faqs.aspx 10/12/15

- (2).Proctor EK, Landsverk J, Aarons G, Chambers D, Glisson C, Mittman B. Implementation research in mental health services: an emerging science with conceptual, methodological, and training challenges. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2009. January;36(1):24–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Madon T, Hofman KJ, Kupfer L, Glass RI. Public health. Implementation science. Science. 2007. December 14; 318(5857):1728–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Colditz Lobb R. Implementation science and its application to population health. Annu Rev Public Health 2012; 34:20.1–20.17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Tavender EJ, Bosch M, Gruen RL, et al. Understanding practice: the factors that influence management of mild traumatic brain injury in the emergency department-a qualitative study using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Implement Sci. 2014;9(1):8. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-9-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Mitchie S, Atkins L, West R The Behaviour Change WheelA Guide To Designing Interventions 2015. Silverback Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Bartholomew LK, Mullen PD. Five roles for using theory and evidence in the design and testing of behavior change interventions.J Public Health Dent. 2011. Winter;71 Suppl 1:S20–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Jagosh J , Bush PL , Salsberg J , Macaulay AC, Greenhalgh T ,Wong G , Cargo M , Green LW , Herbert CP , Pluye PA realist evaluation of community-based participatory research: partnership synergy, trust building and related ripple effects. BMC Public Health. 2015. July 30;15:725. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1949-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Green LW.Public health asks of systems science: to advance our evidence-based practice, can you help us get more practice-based evidence? Am J Public Health. 2006. March;96(3):406–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Handley M, Pasick R, Potter M, Oliva G, Goldstein E, Nguyen T. (2010) Community-Engaged Research: A Quick-Start Guide for Researchers. From the Series: UCSF Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI) Resource Manuals and Guides to Community-Engaged Research, Fleisher P, ed. Published by Clinical Translational Science Institute Community Engagement Program, University of California San Francisco [Google Scholar]

- (11).Gonzales R, Handley MA, Ackerman S, O’Sullivan A Framework for Training Health Professionals in Implementation and Dissemination Science. 2012. Acad Med. 2012. March;87(3):271–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).French SD, Green SE, O’Connor DA, McKenzie JE, Francis JJ, Michie S, Buchbinder R, Schattner P, Spike N, Grimshaw JM.Developing theory-informed behaviour change interventions to implement evidence into practice: a systematic approach using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Implement Sci. 2012. April 24;7:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).RE-AIM. www.re-aim.org.

- (14).Larimer E (personal communication, 2015)