Abstract

Background:

There is limited information on the frequency of complications among older adults after oncological thoracic surgery in the modern era. We hypothesized that morbidity and mortality in older adults with lung cancer undergoing lobectomy is low and different than that of younger patients undergoing thoracic surgery.

Methods:

All patients undergoing lobectomy at a large volume academic center between May 2016 and May 2019 were included. Patients were prospectively monitored to grade postoperative morbidity by organ system, based on the Clavien-Dindo classification. Patients were divided into two groups: Group 1 included patients 65-91 years of age, and Group 2 included those <65 years.

Results:

Of 680 lobectomies in 673 patients, 414(61%) were older than 65 years of age (group 1). Median age at surgery was 68 years (20-91). Median hospital stay was 4 days (1-38) and longer in older adults. Older adults experienced higher rates of grade II and IV complications, mostly driven by an increased incidence of delirium, atrial fibrillation, prolonged air leak, respiratory failure and urinary retention. In this modern cohort, there was only 1 stroke (0.1%), and delirium was reduced to 7%. Patients undergoing minimally invasive (MI) surgery had a lower rate of Grade IV life-threatening complications. Older adults were more likely to be discharged to a rehabilitation facility, however this difference also disappeared with MI surgical procedures.

Conclusions:

Current morbidity of older adults undergoing lobectomy for cancer is low and is different than that of younger patients. Thoracotomy may be associated with postoperative complications in these patients. Our findings suggest the need to consider MI approaches and broad-based, geriatric-focused perioperative management of older adults undergoing lobectomy.

Keywords: Thoracic surgery, Morbidity, Older adult, Minimally invasive surgery, Postoperative outcomes, Oncology outcomes, Lobectomy

1. Introduction

The number of Americans >65 years old is expected to almost double from 52 million in 2018 to 95 million in 2060 [1]. Currently, half of all lung cancer occurs in patients aged ≥65 years [2], With these changing demographics, caring for patients with thoracic malignancy will pose new challenges, and meeting the needs of the aging population will be an integral part of improving the quality of life for older adults with cancer.

Aging affects the physiology of every major organ system [3,4], which can have major effects on the perioperative course of older adults [5], Understanding these physiological changes can help guide their postoperative management, allowing for greater anticipation of postoperative complications and potential reductions in morbidity and mortality. Several studies have demonstrated that older adults are more likely to suffer postoperative complications [6–8], a fact that influences surgical decisions. However, there is limited information on the frequency of complications among older adults after oncological thoracic surgery in the modern era. With the expected growth in the number of older adults, there is a need to better understand postoperative complications among these patients to guide the decision whether to undergo surgery, and optimize their quality of care.

The purpose of this study was to examine the rate and nature of postoperative morbidity and mortality in older adults who underwent lobectomy in a large volume academic center, and compare them with younger patients following lobectomy. We hypothesized that morbidity and mortality in older adults is low, and their pattern of postoperative complications is different from that of younger patients undergoing surgery for cancer. This study services as to identify areas for quality improvement in the postoperative care of these patients.

2. Materials and Methods

All patients undergoing lobectomy for cancer between May 2016 and May 2019 at Brigham and Women’s Hospital were prospectively included. The present study was a retrospective review of prospectively collected data. Minimally invasive procedures included video—assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) and robotic assisted procedures. Thoracotomy incisions requiring the use of a rib spreader to enhance exposure were classified as open procedures.

Demographic, perioperative, pathologic, and discharge disposition data were collected prospectively in a computerized database by the thoracic surgery team. Daily visits to the hospital wards were performed to assess postoperative morbidity and mortality, which included events within 30 days of surgery. Follow-up of patients was complete.

Morbidity was graded based on the Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications [9], This system grades complications on a scale of 1-5. Grade I are minimal complications that require only minor intervention; interventions allowed in this grade include antiemetics, antipyretics, diuretics, and electrolytes. Grade II complications require pharmacological intervention not included in Grade I, or blood products. Grade III complications are those that require surgical, endoscopic or radiologic intervention; grade IV are those in which there is organ dysfunction, and/or requirement of ICU level of care; and finally Grade V are those that result in the patienťs death. Grade I-II complications are considered minor, while complications III-V are considered major events. Only complications Grade II or higher were recorded in this study. All complications had a standardized definition to ensure the same event was captured every time. A definition of all events can be found in the Supplementary Table 1. To characterize the morbidity pattern of these patients, complications were further categorized by organ systems.

All events were audited twice weekly, first by two attending surgeons, followed by a divisional multidisciplinary meeting which included all attending physicians, nursing, and house staffs at the end of the week. The coding of complications into the database from the previous week was reviewed and the nature of complications discussed. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Brigham and Women's Hospital.

2.1. Statistical Analysis

To evaluate the pattern of complications of older adults and younger patients, the cohort was divided into two groups: Group 1 included patients ≥65 years of age and older, and Group 2 included those younger than 65 years. A sub-analysis of only minimally invasive procedures was performed. Descriptive statistics for categorical variables are expressed as frequency and percentages; continuous variables are expressed as mean and standard deviations or median and ranges, as appropriate. Two-tailed Fisher exact test or chi-square were used to compare categorical variables, as appropriate. Mann-U Whitney tests were used for continuous variables. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to identify factors associated with postoperative complications. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 24 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Correction for multiple comparisons within each outcome was performed using the Hochberg sequential test.

3. Results

Between May 2016 and May 2019, 673 patients underwent 680 lobectomies at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Of these, 414 (61%) were older than 65 years of age and were included in group 1. Median age at surgery for the cohort was 68 years (20-91). Surgical approach for lobectomies were VATS in 434 (64%) cases, robotic assisted in 42 (6%) and open procedures in 204 (30%) cases. Younger patients were more likely to undergo open procedures (92/266, 34% vs 112/414, 27%, p< 0.03).

3.1. Postoperative Morbidity

Overall, 241 procedures were complicated, yielding a morbidity rate of 36%, which was higher in older adults. Pulmonary complications were the most frequent (18%) followed by cardiovascular (11%), genitourinary (6%) and neurologic (5%). The complete breakdown of complications is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Postoperative complications by organ system, and discharge disposition in adults ≥65 years compared with adults <65 undergoing lobectomies.

| Variable | ≥65 years |

<65 years |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 414 | n = 266 | ||

| Patients experiencing complications, n (%) | 173 (42) | 68 (26) | <0.001* |

| Complications by organ system | |||

| Neurologic, n (%) | 31 (7) | 3(1) | <0.001* |

| Delirium | 30(7) | 3(1) | <0.001* |

| Stroke | 1 (0.2) | 0 | - |

| Seizures | 1 (0.2) | 0 | - |

| Cardiovascular, n (%) | 63 (15) | 15(6) | <0.001* |

| Atrial fibrillation | 54(13) | 14(5) | <0.001* |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 4(1) | 0 | - |

| Pulmonary embolism | 3 (0.7) | 0 | - |

| Other arrhythmias | 2 (0.5) | 0 | - |

| PEA arrest | 2 (0.5) | 0 | - |

| Pericarditis | 0 | 1 (0.2) | - |

| Pulmonary, n (%) | 83 (20) | 39 (15) | 0.10 |

| Prolonged air leak | 57(14) | 19(7) | 0.007* |

| Pneumonia | 17(4) | 10(4) | 0.82 |

| Respiratory failure | 13(3) | 1 (0.4) | 0.01* |

| Hemothorax | 7(2) | 3(1) | 0.74 |

| Empyema | 5(1) | 1 (0.4) | 0.41 |

| Pneumothorax | 5(1) | 5(2) | 0.52 |

| Pleural effusion | 4(1) | 2 (0.7) | 1.0 |

| Chyle Leak | 3 (0.7) | 2 (0.7) | 1.0 |

| Lobe collapse | 3 (0.7) | 0 | - |

| ARDS | 2 (0.5) | 0 | - |

| Bronchopleural Fistula | 3 (0.7) | 0 | - |

| Lobe infarction | 3 (0.7) | 0 | - |

| Pneumonitis | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.4) | 1.0 |

| Gastrointestinal, n (%) | 2 (0.5) | 0 | - |

| Clostridium difficile infection | 1 (0.2) | 0 | - |

| Genitourinary, n (%) | 35(8) | 4(1) | <0.001* |

| Urinary retention | 20(5) | 1 (0.4) | <0.001* |

| Urinary tract infection | 9(2) | 3(1) | 0.38 |

| AKI | 6(1) | 0 | - |

| Pyelonephritis | 1 (0.2) | 0 | - |

| Renal Failure | 1 (0.2) | 0 | - |

| **Miscellaneous, n (%) | 33 (8) | 20 (8) | 0.83 |

| Transfusion | 23 (6) | 17(6) | 0.77 |

| Technical complication | 4(1) | 1 (0.4) | 0.65 |

| Vocal cord dysfunction | 3 (0.7) | 1 (0.4) | 0.66 |

| Sepsis | 2 (0.5) | 0 | - |

| Wound infection / cellulitis | 2 (0.5) | 0 | - |

| Hemoptysis | 1 (0.2) | 0 | - |

| Hypovolemic shock | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.7) | 0.56 |

| MRSA bacteremia | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.4) | 1.0 |

| Hospital LOS, days, median (range) | 4(1–38) | 4(1–34) | 0.002* |

| Disposition | |||

| Home, n (%) | 362 (87) | 255 (96) | <0.001* |

| Rehabilitation, n (%) | 39 (9) | 5(2) | <0.001* |

| Nursing Home, n (%) | 8(2) | 4(2) | 0.77 |

Bolded p-values were deemed significant after Hochberg sequential adjustment.

AKI = acute kidney injury; ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome; LOS = length of stay PEA = pulseless electric activity; MRSA = methyl-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

Statistically significant

A). Neurologic Complications

Older adults had significantly higher rates of delirium. There was only 1 case of stroke in the cohort, in a 76-year old female who developed multifocal bilateral infarcts and seizures on postoperative day 1 after a right lower lobectomy for a T2a N1 adenocarcinoma. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 21, and at 20 month-follow up has minimal neurologic deficits with no evidence of recurrent adenocarcinoma.

B). Cardiovascular Complications

Atrial fibrillation was the most common complication within cardiovascular morbidity, and the second one most common overall. It was also the only significantly different complication between older and younger patients, and the driver of the significant difference detected in the entire group. There were two cases of pulseless electric activity arrest, not related to myocardial infarction. These will be described further in the operative mortality section.

C). Pulmonary Complications

Prolonged air leak was the most common postoperative complication within pulmonary morbidity and in the whole cohort. The only two statistically significantly different complications between older adults and younger patients were prolonged air leak and respiratory failure. However, after adjusting for multiple comparison procedures this statistical significance disappeared.

D). Gastrointestinal Complications

Gastrointestinal complications that required intervention were not prevalent in the cohort, except for one case of Clostridium difficile treated with Vancomycin in one patient.

E). Genitourinary Complications

The difference noted in genitourinary complications was mostly driven by 21 cases of urinary retention, 14 (67%) of which were male patients. Eleven of these had benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH).

F). Miscellaneous Complications

This group of complications included those that could not be attributed to an organ system, and included mostly hematologic, infectious and technical complications. Transfusions were the most prevalent, with 40 cases overall. All the complications in the miscellaneous group had a similar distribution between younger and older adults, except for sepsis, wound infection and hemoptysis, which occurred in low numbers in older adults only.

As Fig. 1 demonstrates, older adults who received minimally invasive surgery had lower rates of complications in comparison with older adults who underwent thoracotomies. It also shows that their rate of complications is comparable to that of patients younger than 65 years undergoing thoracotomy for lobectomy. The highest rates were in patients undergoing thoracotomy in both groups. On multivariable analysis, the strongest predictor of complications was surgery through thoracotomy. Increasing age and male gender were also independently associated with postoperative complications. (Table 2) An interaction term of operative approach and age was generated and assessed in a regression model. The term was insignificant, with the other variables remaining significant suggesting no evidence of interaction between the two variables; however, the cohort may be underpowered to detect interaction.

Fig. 1.

Morbidity stratified by age and surgical approach. Older adults who received minimally invasive surgery had lower rates of complications in comparison with older adults who underwent thoracotomies. The rate of complications of older adults undergoing minimally invasive surgery is comparable to that of patients younger than 65 years undergoing thoracotomy for lobectomy.

Table 2.

Multivariable logistic regression for postoperative complications.

| Odds ratio | p-value | 95% Cl | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at surgery | 1.04 | <0.001 | 1.02-1.05 |

| Surgical approach | |||

| Minimally invasive | REF | ||

| Thoracotomy | 2.20 | <0.001 | 1.55-3.12 |

| Gender | |||

| Female | REF | ||

| Male | 1.43 | 0.03 | 1.03-1.99 |

Cl = Confidence Interval.

G). Complications by Clavien-Dindo Grade

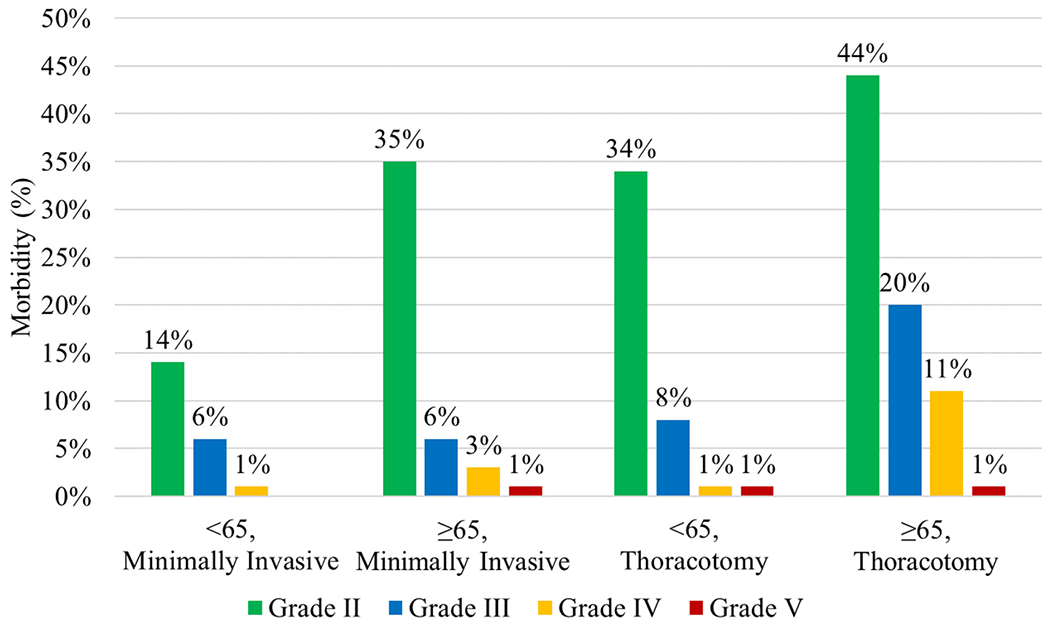

During the study period, 212 (31%) of the procedures developed Grade II complications, 59 (9%) grade III, 23 (3%) grade IV, and 5 (0.7%) grade V complications. Older adults experienced more Grade II [156 (38%) vs 56 (21%), p < 0.001] and Grade IV [20 (5%) vs 3 (1%), p = 0.01] complications than younger patients undergoing lobectomy. Fig. 2 shows the distribution of complications as a function of age, surgical approach and grade. Patients <65 years of age undergoing minimally invasive lobectomies had the lowest rate and severity of complications. The rate of Grade III and IV complications in older adults undergoing lobectomies through a thoracotomy was 20% and 11%, respectively. These rates are over 3 times higher when compared to older adults undergoing lobectomy through a minimally invasive approach.

Fig. 2.

Morbidity stratified by age, surgical approach and grade of complication based on the Clavien-Dindo classification. Patients <65 years of age undergoing minimally invasive lobectomies had the lowest rate and severity of complications. The rate of Grade III and IV complications in patients ≥65 years of age undergoing lobectomies through a thoracotomy was 20% and 11%, respectively. These rates are over 3 times higher when compared to older adults undergoing lobectomy through a minimally invasive approach. Morbidity of older adults undergoing minimally invasive surgery, is comparable to younger patients undergoing thoracotomy.

3.2. Operative Mortality and Disposition

Five patients died within 30-days or before hospital discharge, yielding an operative mortality rate of 0.7%. Four of the five were older adults. Two males, ages 74 and 85 experienced PEA arrest in on postoperative day 31 and 4 respectively. One 80-year old male died on postoperative day 11 secondary to ARDS after family decided to withdraw care. The fourth patient was a 72-year old female who was readmitted with infarction of the right middle lobe after a right upper lobectomy, but succumbed to septic shock on postoperative day 25 of the original operation after family decided to withdraw care. The fifth patient was a 48-year old male who developed intraoperative hemorrhage and could not be resuscitated.

Median hospital stay was 4 days (1-38) and although statistically significantly longer in older adults, the median was 4 days in both groups. Older adults were more likely to be discharged to a rehabilitation facility. (Table 1).

3.3. Subgroup Analysis of Only Minimally Invasive Surgery

Because of the contrasting difference in the rate of complications between open and minimally invasive procedures, we performed a separate analysis of only minimally invasive lobectomies. The results of that analysis are shown in Table 3. Compared to Table 1, which included open procedures too, patients undergoing minimally invasive surgery had a reduced rate of respiratory failure and Grade IV life-threatening complications. Further, the difference in disposition either to rehabilitation facilities or home was no different between older and younger patients.

Table 3.

Selected postoperative complications by organ system, and discharge disposition in adults ≥65 years compared with adults <65 undergoing minimally invasive lobectomies.

| ≥65 years |

<65 years |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 302 | n = 174 | ||

| Patients experiencing complications, n (%) | 115(38) | 32 (18) | <0.001* |

| Complications by organ system | |||

| Neurologic, n (%) | 19(6) | 2(1) | 0.009* |

| Delirium | 18(6) | 2(1) | 0.01* |

| Stroke | 1 (0.3) | 0 | - |

| Seizures | 1 (0.3) | 0 | - |

| Cardiovascular, n (%) | 43 (14) | 8(5) | 0.001* |

| Atrial fibrillation | 36 (12) | 8(5) | 0.008* |

| Pulmonary, n (%) | 50 (17) | 21 (12) | 0.18 |

| Pneumonia | 9(3) | 6(3) | 0.07 |

| Prolonged air leak | 36 (12) | 9(5) | 0.02* |

| Respiratory failure | 5(2) | 1 (0.6) | 0.42 |

| Gastrointestinal, n (%) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | - |

| Genitourinary, n (%) | 21 (7) | 1 (0.6) | 0.001* |

| Urinary retention | 15(5) | 1 (0.6) | 0.008* |

| Urinary tract infection | 5(2) | 0 | - |

| **Miscellaneous, n (%) | 14(5) | 4(2) | 0.06 |

| Hospital LOS, days, median (range) | 4(1–38) | 3 (1–32) | <0.001* |

| Disposition | |||

| Home, n (%) | 280(93) | 169(97) | 0.06 |

| Rehabilitation, n (%) | 14(5) | 3(2) | 0.13 |

| Nursing Home, n (%) | 6(2) | 2(1) | 0.71 |

Bolded p-values were deemed significant after Hochberg sequential adjustment.

LOS = length of stay.

Statistically significant

4. Discussion

It has been reported that age-related physiologic changes lead to reduced physiologic reserve and homeostasis, [3,10] and that stressors such as anesthesia and surgical intervention, may lead to an inadequate functional reserve. These factors may limit the ability of older adults to adequately respond to the stressor, resulting in disease and or complications, in comparison with younger patients [11,12].

Our study was intended to identify areas in which older adults suffer significantly greater rates of complications after surgery, that could serve as opportunities to develop quality improvement efforts. The most common complications in the cohort were prolonged air leak, respiratory failure, atrial fibrillation, delirium and urinary retention, all of which were significantly higher in older adults. These complications appear to be more prevalent with increasing age [13] and as previously reported, may be related to a reduced functional reserve associated with the physiological changes of age [14,15].

Similar to our results, several studies have shown an increased rate of prolonged air leak in older adults [16,17], This may be due to a more fragile lung parenchyma and a reduced healing capacity in this population [5,14]. It has been our approach to follow these air leaks conservatively, since most air leaks resolve on their own [18], In cases in which there was a high-volume leak, or the leak was not trending down, we would consider an interventional approach. In our cohort 6/ 57 (10%) air leaks in the older adult cohort required management through a surgical (n = 4) or interventional (n = 2) approach.

Postural changes of the neck, as well as reduced pharyngeal reflexes in older adults, may predispose patients to aspirate foreign material [14], Decreased chest expansion and shallow breathing may minimize the lung’s ability to clear secretions and bronchial obstructions [19], Both conditions, together with a reduced pulmonary functional capacity in older adults [20,21], may explain the increased rate of respiratory failure in older adults in our cohort. Since patients confined to bed, or those with diminished levels of consciousness are more prone to aspirate [15] we encourage early ambulation and respiratory therapy for airway clearance.

Atrial fibrillation, is one of the most common types of arrhythmias seen in older adults, and the most frequent cardiovascular complication in our cohort. It is believed to be a result from fewer pacemaker cells and considerable deposits of fat and fibrous tissue throughout the cardiac conduction system that occurs with age [21], Although we have implemented several different strategies to address atrial fibrillation, none has successfully reduced the frequency of this source of morbidity. We are currently studying the effects of prophylactic antiarrhythmic in prevention of atrial fibrillation, however, randomized studies may better elucidate an effective prevention regimen in older adults.

The cause of urinary retention in older adults is multifactorial [22], Changes in the bladder with age include decreased capacity and urinary flow rate, increased post-void residual volume, deterioration of detrusor muscle function and changes in neurotransmitter function [23], As men get older the prostate enlarges, causing urinary obstruction to urine flow [15,21], In line with these facts, we found that older adults had a higher incidence of urinary retention than younger patients undergoing lobectomy. Of the 14 male patients with urinary retention, 11 (79%) had a diagnosis of BPH. Based on these results, our institutional practice has been to carefully evaluate the patienťs history for signs and symptoms of BPH, and not to remove urinary catheters in these patients until 24-h resumption of α1-adrenergic receptor antagonists to avoid unnecessary patient discomfort associated with recatheterization.

Structural, functional and metabolic changes in the aging brain affect function and cognition in older adults [24,25], These changes, combined with neuroinflammatory and oxidative mediators, as well as a reduced functional reserve of older adults, cause an imbalance in neural pathways and neurotransmissors that predisposes patients to delirium [26,27], Delirium in older adults has previously been associated with an increase in major complications, mortality, and discharge to a rehabilitation facility [11,28] We have focused in implementing interventions to prevent precipitating factors for delirium such as altered sleep cycle, infection, pain, the use of psychoactive and sedative hypnotic medications, and physiologic or metabolic abnormalities [29,30], Through these interventions, the incidence of delirium in the present study is 7% in older adults (3% for the whole cohort), which are lower than those previously reported, ranging between 15% - 28% [3,31,32].

Overall, minimally invasive surgery in older adults was associated with improved outcomes compared to open thoracotomy. The combination of thoracotomy in patients ≥65 years of age showed the greatest number of complications, and the highest number of Grade III and IV events. Our analysis suggests that age, and surgical approach to a greater extent, independently predict the occurrence of postoperative complications in these patients. These metrics confirms prior reports [33–35] that minimally invasive surgery offers potential advantages to this higher risk population and is associated with better recovery than thoracotomies. When technically possible, we believe that thoracoscopic procedures should be the approach of choice for older adults.

This study has several limitations. First, although we were able to show that there is a difference in the pattern of complications between older and younger patients, we cannot establish the cause of that difference; patient comorbidities, frailty and functional status were not measured, therefore we cannot account for any effect they might have had in the postoperative outcomes of the cohort. Second, the low number of organ-specific postoperative complications does not allow for an analysis of specific risk factors associated with each of these morbidity events. Third, this is a single institution experience; factors such as patient selection and operative technique vary widely across institutions and as such, results may not be generalized to other programs or the general population. At the same time this may be a strength of the present study, because of a more uniform management strategy and followup compared to retrospective multi-institutional studies.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that lobectomy for cancer can be performed in older adults with good morbidity and mortality rates, and confirms the feasibility of surgery for these patients. Carefully selected older adults can undergo lung resection with low morbidity and mortality. There appears to be a difference in the pattern of morbidity between older and younger adults. This difference may be influenced by age-related physiology changes of older adults, however further studies evaluating functional status and frailty may help further answer that question. Older adults undergoing thoracic surgery may benefit from a thorough preoperative assessment and close postoperative monitoring aimed to prevent delirium, prolonged air leak, respiratory failure, atrial fibrillation and urinary retention. These measures may help reduce morbidity in these patients. A thoracoscopic approach may be helpful in reducing morbidity. As such, it should be considered the procedure of choice to minimize the risk of complications in older adults undergoing lobectomy for cancer.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

Drs. De León, Bravo-lñiguez, Fox, Tarascio, Cardin, Frain and Jaklitsch have nothing to disclose.

Dr. DuMontier is supported by the Harvard Translational Research in Aging Training Program (National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health: T32AG023480).

Appendix A. Supplementary Data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2020.09.016.

References

- [1].Colby SL, Ortman JM. Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060. US Census Bureau; 2014; 13. [Google Scholar]

- [2].U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group. U.S. Cancer Statistics Data Visualizations Tool; 1999-2017. https://gis.cdc.gov/grasp/USCS/DataViz.html (accessed August 21, 2019).

- [3].Demeure MJ, Fain MJ. The elderly surgical patient and postoperative delirium. J Am Coll Surg 2006;203:752–7. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Soto-Perez-de-Celis E, Li D, Yuan Y, Lau YM, Hurria A. Functional versus chronological age: geriatric assessments to guide decision making in older patients with cancer. Lancet Oncol 2018. June 1;19(6) e305–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Schlitzkus LL, Melin AA, Johanning JM, Schenarts PJ. Perioperative MANAGEMENT of elderly patients. Surg Clin North Am 2015;95:391–415. 10.1016/j-suc.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Shiono S, Abiko M, Sato T. Postoperative complications in elderly patients after lung cancer surgery. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2013;16:819–23. 10.1093/icvts/ivt034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Berry MF, Hanna J, Tong BC, Burfeind WR, Harpole DH, D’Amico TA, et al. Risk factors for morbidity after lobectomy for lung Cancer in elderly patients. Ann Thorac Surg 2009;88:1093–9. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Suemitsu R, Takeo S, Hamatake M, Yoshino J, Motoyama M, Tanaka H. The perioperative complications for elderly patients with lung Cancer associated with a pulmonary resection under general Anesthesia. J Thorac Oncol 2009;4:193–7. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318194fc4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey JN, Dindo D, Schulick RD, et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg 2009;250:187–96. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bl3ca2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Nicolini F, Agostinelli A, Vezzani A, Manca T, Benassi F, Molardi A, et al. The evolution of cardiovascular surgery in elderly patient: a review of current options and outcomes. Biomed Res Int 2014;2014:1–10. 10.1155/2014/736298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Jones RN, Fong TG, Metzger E, Tulebaev S, Yang FM, Alsop DC, et al. Aging, brain disease, and reserve: implications for delirium. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2010; 18: 117–27. 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181b972e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Pallis AG, Hatse S, Brouwers B, Pawelec G, Falandry C, Wedding U, et al. Evaluating the physiological reserves of older patients with cancer: the value of potential biomarkers of aging? J Geriatric Oncol 2014;5:204–18. 10.10l6/j.jgo.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Seymour DG. Post-operative complications in the elderly surgical patient; 1983; 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Alvis BD, Hughes CG. Physiology considerations in geriatric patients. Anesthesiol Clin 2015;33:447–56. 10.1016/j.anclin.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Steves AM, Dowd SB, Durick D. Caring for the older patient, Part II: age-related anatomic and physiologic changes and pathologies, 13; 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Drewbrook C, Das S, Mousadoust D, Mousadoust D, Mousadoust D, Nasir B, et al. Incidence risk and independent predictors of prolonged air leak in 269 consecutive pulmonary resection patients over nine months: a Single-Center retrospective cohort study. OJTS 2016;06:33–46. 10.4236/ojts.2016.64006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Jiang L, Jiang G, Zhu Y, Hao W, Zhang L. Risk factors predisposing to prolonged air leak after video-assisted Thoracoscopic surgery for spontaneous pneumothorax. Ann Thorac Surg 2014;97:1008–13. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Mueller MR, Marzluf BA. The anticipation and management of air leaks and residual spaces post lung resection. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Venuta F, Diso D, Onorati I, Anile M, Mantovani S, Rendina EA. Lung cancer in elderly patients. J Thorac Dis 2016;8:S908–14. 10.21037/jtd.2016.05.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Colloca G, Santoro M, Gambassi G. Age-related physiologic changes and perioperative management of elderly patients. Surg Oncol 2010;19:124–30. 10.1016/j.suronc2009.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Aalami OO. Physiological features of aging persons. Arch Surg 2003; 138:1068. 10.1001/archsurg.138.10.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Siroky MB. The aging bladder. Rev Urol 2004;6:S3–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Griebling TL. Detrusor underactivity and urinary retention in geriatric patients: evaluation, management and recent research. Curr Bladder Dysfunct Rep 2013;8: 92–100. 10.1007/s11884-013-0183-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Harada CN, Nate Ison Love MC, Triebel KL Normal cognitive aging. Clin Geriatr Med 2013;29:737–52. 10.1016/j.cger.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Peters R. Ageing and the brain. Postgrad Med J 2006;82:84–8. 10.1136/pgmj.2005.036665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Schenning KJ, Deiner SG. Postoperative delirium in the geriatric patient. Anesthesiol Clin 2015;33:505–16. 10.1016/j.anclin.2015.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hshieh TT, Fong TG, Marcantonio ER, Inouye SK. Cholinergic deficiency hypothesis in delirium: a synthesis of current evidence. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2008;63: 764–72. 10.l093/gerona/63.7.764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kalaria RN, Mukaetoca-Ladinska EB. Delirium, dementia and senility. Brain 2012; 135:2581–2. 10.1093/brain/aws228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Fong TG, Tulebaev SR, Inouye SK. Delirium in elderly adults: diagnosis, prevention and treatment. Nat Rev Neurol 2009;5:210–20. 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Inouye SK, Robinson T, Blaum C, Busby-Whitehead J, Boustani M, Chalian A, et al. Postoperative delirium in older adults: best practice statement from the american geriatrics society. J Am Coll Surg 2015;220:136–48 e1 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Robinson T Postoperative delirium in the elderly: diagnosis and management. CIA 2008;3:351–5. 10.2147/CIA.S2759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Khan BA, Perkins AJ, Campbell NL, Gao S, Khan SH, Wang S, et al. Preventing postoperative delirium after major noncardiac thoracic surgery—a randomized clinical trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018;66:2289–97. 10.1111/jgs.15640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Cerfolio RJ, Bryant AS. Survival and outcomes of pulmonary resection for non-small cell lung Cancer in the elderly: a nested case-control study. Ann Thorac Surg 2006; 82:424–30. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.02.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Jaklitsch MT, DeCamp MM, Liptay MJ, Harpole DH, Swanson SJ, Mentzer SJ, et al. Video—assisted thoracic surgery in the elderly. Chest 1996;110:751–8. 10.1378/chest.l10.3.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Jaklitsch MT, Pappas-Estocin A, Bueno R. Thoracoscopic surgery in elderly lung cancer patients. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2004;49:165–71. 10.1016/j-critrevonc2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.