Abstract

Purpose:

To evaluate the acceptability and impact of 3D printed breast models (3D-BM) on treatment-related decisional conflict (DC) of breast cancer patients.

Methods:

Patients with breast cancer were accrued in a prospective IRB-approved trial. All patients underwent contrast-enhanced breast MRI (MRI). A personalized 3D-BM was derived from MRI. DC was evaluated pre and post 3D-BM review. 3D-BM acceptability was assessed post 3D-BM review.

Results:

DC surveys before and after 3D-BM review and 3D-BM acceptability surveys were completed by 25 patients. 3D-BM were generated in 2 patients with bilateral breast cancer. The mean patient age was 48.8 years (28–72). Tumor stage was Tis (7), 1 (8), 2 (8) and 3 (4). Nodal staging was 0 (19), 1 (7), 3 (1). Tumors were unifocal (15), multifocal (8) or multicentric (4). Patients underwent mastectomy (13) and segmental mastectomy (14) with (20) or without (7) oncoplastic intervention. Neoadjuvant therapy was given to 7 patients. Patients rated the acceptability of the 3D-BM as good/excellent in understanding their condition (24/24), understanding disease size (25/25), 3D-BM detail (22/25), understanding their surgical options (24/25), encouraging to ask questions (23/25), 3D-BM size (24/25) and impartial to surgical options (17/24). There was significant reduction in overall DC post 3D-BM review, indicating patients became more assured of their treatment choice (p=0.002). Reduction post 3D-BM review was also observed in the uncertainty (p=0.012), feeling informed about options (p=.005), clarity about values (p=0.032) and effective (p=0.002) DCS subscales.

Conclusions:

3D-BMs are an acceptable tool to decrease decisional conflict in breast cancer patients.

Clinical relevance:

Breast cancer patients may experience decisional conflict when considering their surgical options. 3D-BM are an acceptable, impartial tool that reduces decisional conflict in patients with breast cancer.

Keywords: Breast cancer, 3D printing, decisional conflict, acceptability

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common solid malignancy in women in the United States [1], Surgical options include mastectomy and segmental mastectomy (BCS). When adjunct radiation therapy is offered, BCS has been shown to have similar outcomes to mastectomy [2, 3]. The availability of various treatment options with similar outcomes may result in decisional conflict during the decision making process due to uncertainty, anticipated regret, and emotional discomfort associated with these options [4, 5]. The rates of regret in breast cancer survivors range from 9.1–43% in breast cancer survivors [6–8]. Therefore when both surgical options are available, the decision process should incorporate patienťs needs and values also known as preference-sensitive care [9]. Participation in the decision-making process has been associated with lower likelihood of dissatisfaction and regret [1, 6, 8, 10, 11]. Greater incidence of regret has been observed in patients that expressed difficulties with patient-physician communication and insufficient information regarding treatment options and adverse side effects [6].

Several case studies have reported how personalized 3D printed models facilitate a patienťs understanding of anatomy and the goal of the proposed surgical management [12–17]. A personalized 3D printed breast model (3D-BM) is a physical representation of the findings identified in the patienťs contrast enhanced breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) exam. The 3D-BM may be used during the consultation process as an adjunct communication aid. The purpose of our study is to evaluate the acceptability and impact of personalized 3D-BM on treatment-related decisional conflict (DC) in breast cancer patients.

Methods

Study population

Women older than 18 years of age diagnosed with breast cancer at a large comprehensive cancer center and 2 regional practice locations were prospectively enrolled in an institutional review board (IRB) approved, HIPAA-compliant study from January 2018 through May 2019. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants in the study. All patients underwent digital mammography (DM), whole-breast ultrasound (US) and contrast-enhanced breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Patients enrolled were all candidates for surgical management.

Imaging equipment

Patients underwent imaging at the comprehensive cancer center and 1 regional imaging center. DM at both locations was performed using Hologic Selenia Dimensions mammography systems (Hologic Inc, Bedford, MA, USA). US was performed using EPIQ 5 systems with 12- to 18 MHz high-frequency linear array transducers (Philips Healthcare, Andover, MA, USA). MRI was performed before and following intravenous contrast administration using 3T MRI scanners (Signa HDxt; GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI, USA and Magnetom Skyra; Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany) using a 16-channel dedicated breast coil.

3D printed breast models

A personalized 3D-BM was created from the MRI and cross-referenced to the information provided by the patient’s DM and US. Segmentation of the anatomy of interest and post processing of each model was performed using a commercially available software (InPrint 2.0, Materialise, Leuven, Belgium). The average segmentation time was 4.8 hours (range 2–12 hours). This time was dependent on the 1) operator’s experience with the segmentation software, 2) disease presentation as non-mass enhancement and 3) background enhancement, which intermingled with disease. The 3D-BMs were constructed using UV-cured photopolymer resin material using stereolithography (SLA) printers (Forms 2, Formlabs, Somerville, MA, USA). The average volume of material for the models was 317.2 mL (range 91.9 – 600 mL) resulting in an average cost of $47.23 (range $13.69 - $ 89.40). Post-processing of each model was performed to highlight anatomy and ensure stability of the 3D-BM.

Questionnaires

Decisional conflict was evaluated using the Decisional Conflict Scale© (DCS), which consists of a 16-item survey including 5 subscales that evaluate how individuals perceive how informed they are (3 items), impact on their personal values (3 items), level of support they have (3 items), degree of uncertainty they feel regarding their decision (3 items) and their effectiveness in making choices (4 items)[18]. The DCS has been shown to be a strong predictor for decision delay, regret and change in decisions or implementation delays [19, 20]. Overall DCS scores greater than 37.5 on a 100-point scale have been associated with decision delay or feeling unsure about the implementation of a patient’s decision [19, 20]. An overall score lower than 25 indicates low decisional conflict and an association with implementation of decisions [20].

Wording was adapted to address surgical options in breast cancer. The survey was conducted at 2 time points. The initial survey was conducted after the standard of care consultation with a breast surgeon and prior to the review of the 3D-BM. The standard of care consultation with a breast surgeon at our institution includes review of breast imaging exams results comprising of DM, US and MRI as well as discussion of pathology results and surgical options including mastectomy, BCS with or without oncoplastic reconstruction. Once the first-time point DCS survey was completed, the 3D-BM was reviewed by patients in conjunction with the breast surgeon or radiologist. The second-time point DCS survey was completed following review of the personalized 3D-BM. The overall decisional conflict score reflects a patienťs degree of conflict from 0 (no conflict) to 100 (high conflict).

Acceptability of the 3D-BM was assessed using the Ottawa acceptability questionnaire consisting of a 10-item survey [21]. The survey wording was adapted to define the 3D-BM as the decision aid to be assessed. The survey evaluates how patients perceive the 3D-BM in 5 performance categories. The acceptability survey was provided following review of the personalized 3D-BM. Unanswered items were excluded from analysis.

Statistical analysis

Patient demographics, tumor characteristics, pre- and post-DCS scores were summarized using frequencies, percentages, means, standard deviations, medians, minimums, and maximums. Pre- and post-DCS scores were compared using paired sample t-test. The associations of pre-DCS score (or score change) with clinical and tumor characteristics were tested using Wilcoxon Rank Sum test or Kruskal-Wallis test with Steel-Dwass procedure. Patient surgical choice was tabulated with acceptability bias and tested using Fisher’s exact test. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were carried out using R (version 3.6.3, R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria).

Results

A total of 30 patients were enrolled (n=30). 3D printed breast models (3D-BM) were created for 30 patients. Decisional conflict and acceptability surveys were completed by 25 patients. A total of 27 3D-BM were created for the 25 patients as 23 patients presented with unilateral breast cancer and 2 patients presented with bilateral breast cancer. The mean patient age was 48.8 years (28–72 years). Tumors presented as a single focus or unifocal (15), multifocal or more than 2 sites of disease in the same quadrant (8) and multicentric or more than 2 sites of disease in different quadrants (4). Clinico-pathologic features are summarized in Table 1. BCS was performed for 14 breast cancers, while mastectomy was performed for 13 breast cancers. Concomitant oncoplastic surgery; tissue rearrangement (9), implant-based reconstruction (10) and flap-based reconstruction (1), was performed in 20 cases, 11 of which were in the setting of BCS and 9 were in the setting of mastectomy. Seven patients underwent neoadjuvant therapy. Most patients (17/25, 68%) expressed a preference for a particular surgical option, either BCS (10/25, 40%) or mastectomy (7/25, 28%), at the time of surgical consult. The patients unsure of their surgical option (8/25, 32%) underwent BCS (4) or mastectomy (4) in equal proportion.

Table 1.

Clinico-pathologic features of tumors that underwent creation of a personalized 3D-printed breast model (3D-BM).

| Breast cancer feature | Number |

|---|---|

| Histology* | |

| DCIS | 7 |

| IDC | 7 |

| IDC-DCIS | 6 |

| ILC | 6 |

| Other | 1 |

| Grade | |

| 1 | 7 |

| 2 | 9 |

| 3 | 11 |

| Tumor stage | |

| Tis | 7 |

| T1 | 8 |

| T2 | 8 |

| T3 | 4 |

| Nodal stage | |

| N0 | 19 |

| N1 | 7 |

| N3 | 1 |

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC), invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC).

Decisional Conflict

Overall population

The mean overall DCS score prior to 3D-BM review was 16.5 (SD, 15.3). Following review of the 3D-BM, the mean overall DCS score was 10.5 (SD, 14.1). There was a significant reduction in overall decisional conflict scores following review of the 3D-BM (p= 0.002). Statistically significant decreased decisional conflict scores following 3D-BM review were observed in 4 of the 5 subscales including uncertainty about choices, knowledge/informed, incorporation of personal values and effective decision making. No significant change was observed in the support level subscale following 3D-BM review (Table 2).

Table 2.

Decisional conflict subscales (DCS) scores prior to- and following 3D printed breast model (3D-BM) review.

| Subscale | Pre 3DM review mean (Std Dev) | Post 3DM review mean (Std Dev) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uncertainty | 24.1 (20.7) | 14.7 (19.9) | 0.012 |

| Informed | 15.3 (18.0) | 8.3 (12.0) | 0.005 |

| Values | 16.7 (20.0) | 10.0 (14.8) | 0.032 |

| Support | 9.3 (11.9) | 7.3 (11.4) | 0.185 |

| Effective | 17.3 (17.8) | 9.8 (16.3) | 0.002 |

Surgical preference

The mean overall DCS score prior to 3D-BM review was significantly greater in patients unsure of their surgical options/choice (30.9, 15.2 Std Dev) compared to those that stated a surgical preference for breast conservation (p = 0.0198) or mastectomy (p = 0.0121). There was no significant difference in the mean overall DCS score prior to 3D-BM review between patients that stated a preference for BCS versus those preferring mastectomy (0.71).

A significant difference was also observed following 3D-BM review between patients unsure of their surgical options/choice and those with a stated surgical preference in 4 of 5 subscales including uncertainty about choices (p = 0.001), knowledge/informed (p = 0.047), feeling supported in their decision making (p = 0.019) and effective decision making (p < 0.001).

Factors such as ethnicity, neoadjuvant therapy, histology, tumor grade, T status, N status, focality, surgery performed and oncoplastic interventions were not associated with changes in DCS scores before and following 3D-BM review (Table 3).

Table 3.

Decisional conflict (DCS) scores by covariates prior to- and post 3D printed breast model (3D-BM) review.

| Feature | DCS mean score (SD) pre 3D-BM | P value | DCS mean score change (SD) post 3D-BM | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | 0.415 | 0.294 | ||

| African American | 13.3 (16.6) | −0.80 (1.1) | ||

| Asian | 25.0 (23.6) | −2.60 (2.4) | ||

| Caucasian | 13.0 (15.4) | −6.2 (10.0) | ||

| Hispanic | 23.1 (9.0) | −9.7 (8.8) | ||

| Neoadjuvant therapy | 0.247 | 0.855 | ||

| Yes | 18.8 (16.6) | −6.7 (10.2) | ||

| No | 10.5 (10.0) | −4.3 (3.8) | ||

| Histology* | 0.198 | 0.311 | ||

| DCIS | 29.2 (22.4) | −8.2 (14.5) | ||

| IDC | 14.51 (9.8) | −7.0 (5.3) | ||

| IDC-DCIS | 18.0 (11.0) | −7.6 (9.4) | ||

| ILC | 5.6 (5.1) | −1.6 (2.5) | ||

| Other | 0.00 (N/A) | 0.0 (N/A) | ||

| Tumor grade | 0.420 | 0.937 | ||

| 1 | 11.0 (16.6) | −8.6 (14.4) | ||

| 2 | 15.2 (10.9) | −5.9 (8.8) | ||

| 3 | 20.5 (17.5) | −4.8 (4.8) | ||

| T status | 0.380 | 0.985 | ||

| Tis | 29.2 (22.4) | −8.2 (14.5) | ||

| T1 | 13.3 (11.2) | −7.0 (9.0) | ||

| T2 | 13.9 (10.8) | −4.1 (4.4) | ||

| T3 | 6.8 (5.9) | −4.2 (4.8) | ||

| N status | 0.607 | 0.901 | ||

| N0 | 16.1 (16.6) | −7.1 (10.1) | ||

| N1 | 15.1 (11.9) | −3.7 (3.3) | ||

| N3 | 1.6 (N/A) | −1.6 (N/A) | ||

| Focality | 0.600 | 0.957 | ||

| Unifocal | 19.1 (15.6) | −6.9 (10.1) | ||

| Multifocal | 12.1 (16.2) | −5.4 (8.2) | ||

| Multicentric | 16.1 (14.5) | −3.6 (3.9) | ||

| Surgery performed | 0.720 | 0.408 | ||

| Breast conserving surgery (BCS) | 17.6 (16.0) | −5.1 (7.5) | ||

| Mastectomy | 15.1 (15.1) | −7.2 (10.6) | ||

| Oncoplastic intervention | 0.447 | 0.815 | ||

| Implant expander/implant | 18.4 (14.8) | −7.8 (11.8) | ||

| Flap-based reconstruction | 1.6 (N/A) | −1.6 (N/A) | ||

| None | 10.2 (11.4) | −5.5 (5.8) | ||

| Tissue rearrangement | 20.5 (18.1) | −5.1 (8.2) | ||

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC), invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC).

Acceptability

The personalized 3D-BM’s were rated as excellent or good in 5 acceptability categories including its impact on patient’s understanding of their breast cancer, disease size, breast components, surgical options, and encouraging discussion. The size and amount of detail in the 3D-BM was rated “just right” by most patients (Figure 1). Variable rating was reported in the ability of the 3D-BM to elicit an emotional response (Table 4). The majority of patients rated the 3D-BM to be without bias towards a particular surgical option (Table 5). When patients rated the 3D-BM biased towards either mastectomy or segmental mastectomy, the bias reported was concordant with the patient’s preferred and/or final surgical option for mastectomy or segmental mastectomy. A patient’s surgical choice was significant associated with perceived bias in the 3D-BM (p = 0.046).

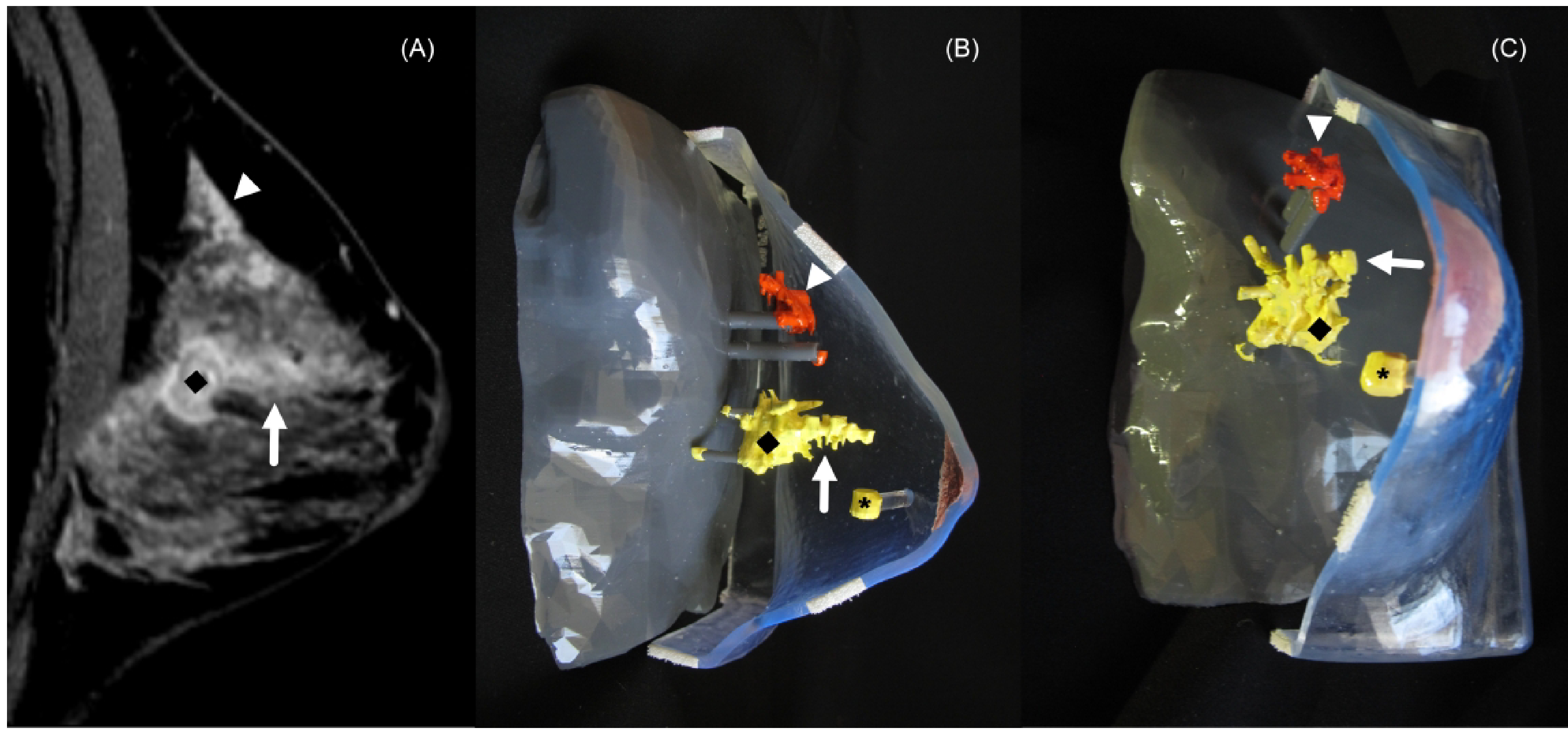

Figure 1.

44-year-old woman with right breast invasive ductal carcinoma and ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). (A) Sagittal contrast-enhanced breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrating an enhancing mass (diamond) and adjacent non-mass enhancement (arrow) and distant non-mass enhancement (arrowhead). Lateral (B) and frontal (C) views of the 3D-printed breast model (3D-BM) demonstrate the mass (diamond), adjacent non-mass enhancement (arrow), distant non-mass enhancement (arrowhead) and clip artifact denoting the site of DCIS (asterisk). The 3D-BM depicts areas of biopsy proven disease is in yellow and areas of suspected disease are depicted in orange. Surgical pathology confirmed invasive ductal carcinoma grade 3 measuring 3.3 cm and DCIS spanning 9.3 cm.

Table 4.

Acceptability rating for the 3D printed breast model (3D-BM).

| Acceptability feature | Overall (N=27) |

|---|---|

| Impact in understanding breast cancer | |

| Excellent | 16 (66.7%) |

| Good | 8 (33.3%) |

| Understanding disease size | |

| Excellent | 19 (76.0%) |

| Good | 6 (24.0%) |

| Breast components | |

| Excellent | 19 (76.0%) |

| Good | 3 (12.0%) |

| Fair | 3 (12.0%) |

| Understanding surgical options | |

| Excellent | 19 (76.0%) |

| Good | 5 (20.0%) |

| Fair | 1 (4.0%) |

| Promoting asking questions | |

| Excellent | 19 (76.0%) |

| Good | 4 (16.0%) |

| Fair | 2 (8.0%) |

| Eliciting an emotional response | |

| Excellent | 11 (45.8%) |

| Good | 8 (33.3%) |

| Fair | 1 (4.2%) |

| Poor | 4 (16.7%) |

| Detail of the 3D-BM | |

| Just right | 23 (92.0%) |

| Too little | 2 (8.0%) |

| Bias | |

| Balanced | 18 (72.0%) |

| Bias to BCS* | 4 (16.0%) |

| Bias to mastectomy | 3 (12.0%) |

| Helpfulness in decision making | |

| Yes | 25 (100.0%) |

| Informative | |

| Yes | 25 (100.0%) |

| Influence of surgical consult discussion in decision making | |

| Easier | 23 (92.0%) |

| More difficult | 1 (4.0%) |

| Neither | 1 (4.0%) |

| Quantity of information provided in the model | |

| No | 2 (8.0%) |

| Yes | 23 (92.0%) |

BCS: Breast conserving surgery

Table 5.

Evaluation of bias in the 3D printed breast model (3D-BM) according to patient’s surgical choice.

| Surgical choice | Balanced (N=18) | Bias to BCS (N=4) | Bias to mastectomy (N=3) | Total (N=25) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.046 | |||||

| BCS* | 6 (33.3%) | 4 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 10 (40.0%) | |

| Mastectomy | 5 (27.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (66.7%) | 7 (28.0%) | |

| Unsure | 7 (38.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (33.3%) | 8 (32.0%) | |

BCS: Breast conserving surgery

Discussion

Our study demonstrates the acceptability of personalized 3D-BM and their impact in decreasing decisional conflict in patients with breast cancer evaluating their surgical options. Personalized 3D-BM influence various elements in the decision making process including the depth of information regarding treatment options, benefits, risks and side effects, integration of personal values, uncertainty in choices and effectiveness in decision making. An enhanced decision making process will allow patients to reach value-based decisions and therefore improve satisfaction and regret.

The decision-making process regarding breast cancer surgery is often complex, multifactorial and influenced by the sources of information used by the patient, patient values and patient age among others [22, 23]. Such a decision-making process often entails decisional conflict. An individual may experience decisional conflict when there is uncertainty regarding a course of action where the choice involves risk, the outcome is uncertain, or when personal values may be compromised [24–26]. The Decisional Conflict Scale© (DCS) is a validated tool that measures an individual’s perception of uncertainty in choosing among health care options, the factors associated with their uncertainty and the quality of the decision made [24]. Overall DCS scores are a strong predictor of regret, delay in decision making and changing or discontinuing decisions [19].Some patient groups have been shown to experience less satisfaction and greater regret when considering treatment options for breast cancer [27, 28].

Decision aids have been developed to assist patients in the decision making process after the diagnosis of breast cancer with variable results [29–33]. Tailored, interactive aids have been shown to improve patient’s decision quality by enhancing a patient’s knowledge and decreasing decisional conflict [29, 34–37]. Prior studies have demonstrated the need to overcome gaps in knowledge that may lead to increased decisional conflict [23,27,29]. 3D printed models have been used in medicine for the creation of personalized anatomical models, surgical guides and custom implants enhancing preoperative planning and intraoperative efficiency [12–17, 38–42]. 3D printed personalized models have also been used to enhance patient-physician communication and the consent process in various diseases [43–46]. Our work demonstrates the value of personalized 3D-BM in the decision making process in the surgical treatment of breast cancer. Following the use of 3D-BM, there was a significant decrease in the overall DCS score following review of the 3D-BM in our study population. Although 3D-BM may not serve as standalone decision aids because they do not provide information regarding various surgical options and their benefits and risks, they foster discussion of these options to help patients make value-based choices. The impact of 3D-BM on DCS scores in our population is in accordance with the study by Whelan et al that evaluated a traditional decision board which integrated information about treatment options, acute and long-term adverse effects associated with treatment, long-term survival and quality of life [32]. In their study the mean overall DCS score for the control group was similar to the pre 3D-BM review scores in our study. Similarly in their study the mean overall DCS scores for the decision aid group was similar to the post 3D-BM review scores in our study. A corresponding significant decrease in the uncertainty, knowledge/informed, incorporation of personal values and effective decision making DCS subscales was also noted. The impact of uncertainty is reflected by the significantly greater DCS scores for patients unsure of their surgical options/choice compared to those that stated a surgical preference. The impact of decision aids on DCS subscales in the surgical treatment of early breast cancer has been limited [47]. This study which compared a decision aid, tape and workbook to the standard-of-care pamphlet given to the control group demonstrated no significant difference in the DCS subscales between the groups [47].

The personalized 3D-BM were rated as excellent or good in 5 acceptability categories. The high ratings reflect an appropriate amount of content within the 3D-BM. Appropriate content has been shown to be associated with improved efficacy of such interventions [24]. In addition most patients reported a lack of bias towards a particular surgical option for the 3D-BM. When bias was reported, it was concordant with the patienťs preferred and/or final surgical option. This alignment between a patienťs understanding (cognition) and choice (behavior) is in accordance with the theory of cognitive dissonance [48]. This theory proposes that in order to minimize internal conflict, an individual will be motivated to accept their decision. This alignment is observed in the concordance between the bias perceived in the 3D-BM (cognition) and the chosen surgical treatment option (behavior). Thus patients view the tool; 3D-BM based on their preferred treatment.

Our study is limited by the small sample size and lack of a comparison group that did not receive the 3D-BM. As timepoints for DCS questionnaire completion occurred within the same day of the consult, some patients may have been primed to give greater attention to their values and treatment options than they would have if completing the initial DCS during a different visit. These results may be further validated in larger scale studies that encompass patients at various stages of the decision making process as well as patients considering neoadjuvant therapy. Downstream outcomes such as decisional regret should also be considered in larger comparative trials.

We have demonstrated the feasibility of creating 3D-BM and their implementation in clinical care. Our study demonstrates 3D-BM is acceptable to patients and may decrease decisional conflict for women undergoing surgical treatment of breast cancer. 3D-BM are able to overcome language, cultural and educational barriers thereby enhancing a patient’s knowledge about their disease, which in turns improves their uncertainty and effectiveness in decision making.

Acknowledgments

Grant support:

The John S. Dunn Sr. Distinguished Chair in Diagnostic Imaging.

The Robert D. Moreton Distinguished Chair in Diagnostic Radiology.

The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health through Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA016672, The Shared Decision Making Core (RJV).

Abbreviations:

- 3D-BM

3-dimension printed breast model

- CI

confidence interval

- ER

estrogen receptor

- HER2

human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- HIPAA

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

- IRB

institutional review board

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- NAST

neoadjuvant systemic therapy

- PR

progesterone receptor

- SD

standard deviation

Footnotes

Synopsis

We evaluated the feasibility of incorporating patient specific 3-dimensional (3D) printed models for patients with breast cancer evaluating surgical treatment options. We assessed the acceptability of the 3D printed models and their impact in the patienťs decisional conflict. Decisional conflict for each patient was measured following standard of care surgical consultation and after review of the 3D printed model. Acceptability of the 3D model by patients was also evaluated to determine adequacy of the design and possible bias. The 3D printed breast models were deemed acceptable and without bias by our patients. There was a significant decrease in decisional conflict when 3D printed models were incorporated. Therefore, patient-specific 3D printed models can be integrated during the surgical consult to enhance decision-making and decrease decisional conflict.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Funding: This project was supported in part by a grant from National Institutes of Health through Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA016672, the John S. Dunn Sr. Distinguished Chair in Diagnostic Imaging, and the Robert D. Moreton Distinguished Chair in Diagnostic Radiology and used the Shared Decision Making Core (RJV).

Conflict of Interest:

Robert J. Volk, PhD declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Dalliah Black, MD declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Cristina M. Checka, MD declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Joanna Lee, MD declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Jessica Suarez Colen, MD declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Catherine Akay, MD declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Abigail Caudle, MD declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Henry Kuerer, MD, PHD declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Elsa M. Arribas, MD declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in this study.

Data Availability Statement:

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Montgomery LL, Tran KN, Heelan MC, Van Zee KJ, Massie MJ, Payne DK, Borgen PI: Issues of regret in women with contralateral prophylactic mastectomies. Annals of surgical oncology 1999, 6(6):546–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fisher B, Anderson S, Bryant J, Margolese RG, Deutsch M, Fisher ER, Jeong JH, Wolmark N: Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast cancer. The New England journal of medicine 2002, 347(16):1233–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Veronesi U, Cascinelli N, Mariani L, Greco M, Saccozzi R, Luini A, Aguilar M, Marubini E: Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized study comparing breast-conserving surgery with radical mastectomy for early breast cancer. The New England journal of medicine 2002, 347(16):1227–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gu J, Groot G, Boden C, Busch A, Holtslander L, Lim H: Review of Factors Influencing Women's Choice of Mastectomy Versus Breast Conserving Therapy in Early Stage Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review. Clinical breast cancer 2018, 18(4):e539–e554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gumus M, Ustaalioglu BO, Garip M, Kiziltan E, Bilici A, Seker M, Erkol B, Salepci T, Mayadagli A, Turhal NS: Factors that Affect Patients' Decision-Making about Mastectomy or Breast Conserving Surgery, and the Psychological Effect of this Choice on Breast Cancer Patients. Breast Care (Basel) 2010, 5(3):164–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernandes-Taylor S, Bloom JR: Post-treatment regretamong young breast cancer survivors. Psycho-oncology 2011, 20(5):506–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang AW, Chang SM, Chang CS, Chen ST, Chen DR, Fan F, Antoni MH, Y Hsu W: Regret about surgical decisions among early-stage breast cancer patients: Effects of the congruence between patients' preferred and actual decision-making roles. Psycho-oncology 2018, 27(2):508–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lantz PM, Janz NK, Fagerlin A, Schwartz K, Liu L, Lakhani I, Salem B, Katz SJ: Satisfaction with surgery outcomes and the decision process in a population-based sample of women with breast cancer. Health services research 2005, 40(3):745–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wennberg JE: Unwarranted variations in healthcare delivery: implications for academic medical centres. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2002, 325(7370):961–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheehan J, Sherman KA, Lam T, Boyages J: Association of information satisfaction, psychological distress and monitoring coping style with post-decision regret following breast reconstruction. Psycho-oncology 2007, 16(4):342–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheehan J, Sherman KA, Lam T, Boyages J: Regret associated with the decision for breast reconstruction: the association of negative body image, distress and surgery characteristics with decision regret. Psychology & health 2008, 23(2):207–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernhard J-C, Isotani S, Matsugasumi T, Duddalwar V, Hung AJ, Suer E, Baco E, Satkunasivam R, Djaladat H, Metcalfe C et al. : Personalized 3D printed model of kidney and tumor anatomy: a useful tool for patient education. World J Urol 2016, 34(3):337–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Porpiglia F, Bertolo R, Checcucci E, Amparore D, Autorino R, Dasgupta P, Wiklund P, Tewari A, Liatsikos E, Fiori C et al. : Development and validation of 3D printed virtual models for robot-assisted radical prostatectomy and partial nephrectomy: urologists' and patients' perception. World J Urol 2018, 36(2):201–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santiago L, Adrada BE, Caudle AS, Clemens MW, Black DM, Arribas EM: The role of three-dimensional printing in the surgical management of breast cancer. J Surg Oncol 2019, 120(6):897–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmit C, Matsumoto J, Yost K, Alexander A, Ness L, Kurup AN, Atwell T, Leibovich B, Schmit G: Impact of a 3D printed model on patients' understanding of renal cryoablation: a prospective pilot study. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2019, 44(1):304–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silberstein JL, Maddox MM, Dorsey P, Feibus A, Thomas R, Lee BR: Physical models of renal malignancies using standard cross-sectional imaging and 3-dimensional printers: a pilot study. Urology 2014, 84(2):268–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wake N, Rosenkrantz AB, Huang R, Park KU, Wysock JS, Taneja SS, Huang WC, Sodickson DK, Chandarana H: Patient-specific 3D printed and augmented reality kidney and prostate cancer models: impact on patient education. 3D Print Med 2019, 5(1):4–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Connor AM: Validation of a decisional conflict scale. Med Decis Making 1995, 15(1):25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun Q: Predicting downstream effects of high decisional conflict: Meta-analyses of the decisional conflict scale.: University of Ottawa; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 20.User Manual - Decisional Conflict Scale (16 item statement format) [https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/docs/develop/User_Manuals/UM_Decisional_Conflict.pdf]

- 21.User Manual - Acceptability [https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/docs/develop/User_Manuals/UM_Acceptability.pdf] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmidt H, Cohen A, Mandeli J, Weltz C, Port ER: Decision-Makingin Breast Cancer Surgery: Where Do Patients Go for Information? Am Surg 2016, 82(5):397–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bleicher RJ, Abrahamse P, Hawley ST, Katz SJ, Morrow M: The influence of age on the breast surgery decision-making process. Annals of surgica loncolog y 2008. 15(3):854–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garvelink MM, Boland L, Klein K, Nguyen DV, Menear M, Bekker HL, Eden KB, LeBlanc A, O’Connor AM, Stacey D et al. : Decisional Conflict Scale Use over 20 Years: The Anniversary Review. Medical Decision Making 2019, 39(4):301–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Janis IL, Mann L: Decision making: A psychological analysis of conflict, choice, and commitment. New York, NY, US: Free Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Connor AM, Legare F.: Decisional conflict. In: Encyclopedia of Medical Decision Making edn. Edited by Kattan MW. San Diego, California: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hawley ST, Griggs JJ, Hamilton AS, Graff JJ, Jazw NK, Morrow M, Jagsi R, Salem B, Katz SJ: Decision involvement and receipt of mastectomy among racially and ethnically diverse breast cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst 2009, 101(19):1337–1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenberg SM, Tracy MS, Meyer ME, Sepucha K, Gelber S, Hirshfield-Bartek J, Troyan S, Morrow M, Schapira L, Come SE et al. : Perceptions, knowledge, and satisfaction with contralateral prophylactic mastectomy among young women with breast cancer: a cross-sectional survey. Annals of internal medicine 2013, 159(6):373–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hawley ST, Li Y, An LC, Resnicow K, Janz NK, Sabel MS, Ward KC, Fagerlin A, Morrow M, Jagsi R et al. : Improving Breast Cancer Surgical Treatment Decision Making: The iCanDecide Randomized Clinical Trial. J Clin Oncol 2018, 36(7):659–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nicholas Z, Butow P, Tesson S, Boyle F: A systematic review of decision aids for patients making a decision about treatment for early breast cancer. The Breast 2016, 26:31–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Waljee JF, Rogers MAM, Alderman AK: Decision Aids and Breast Cancer: Do They Influence Choice for Surgery and Knowledge of Treatment Options? Journal of Clinical Oncology 2007, 25(9):1067–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whelan T, Levine M, Willan A, Gafni A, Sanders K, Mirsky D, Chambers S, O'Brien MA, Reid S, Dubois S: Effect of a decision aid on knowledge and treatment decision making for breast cancer surgery: a randomized trial. Jama 2004, 292(4):435–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Street RL Jr, Voigt B, Geyer C Jr, Manning T, Swanson GP: Increasing patient involvement in choosing treatment for early breast cancer. Cancer 1995, 76(11):2275–2285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trikalinos TA, Wieland LS, Adam GP, Zgodic A, Ntzani EE: AHRQ Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. In: Decision Aids for Cancer Screening and Treatment. edn. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O'Brien MA, Whelan TJ, Villasis-Keever M, Gafni A, Charles C, Roberts R, Schiff S, Cai W: Are cancer-related decision aids effective? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol 2009, 27(6):974–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Belkora JK, Volz S, Teng AE, Moore DH, Loth MK, Sepucha KR: Impact of decision aids in a sustained implementation at a breast care center. Patient Educ Couns 2012, 86(2):195–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waljee JF, Rogers MA, Alderman AK: Decision aids and breast cancer: do they influence choice for surgery and knowledge of treatment options? J Clin Oncol 2007, 25(9):1067–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tack P, Victor J, Gemmel P, Annemans L: 3D-printing techniques in a medical setting: a systematic literature review. Biomed Eng Online 2016, 15(1):115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Teishima J, Takayama Y, Iwaguro S, Hayashi T, Inoue S, Hieda K, Shinmei S, Kato R, Mita K, Matsubara A: Usefulness of personalized three-dimensional printed model on the satisfaction of preoperative education for patients undergoing robot-assisted partial nephrectomy and their families. Int Urol Nephrol 2018, 50(6):1061–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pugliese L, Marconi S, Negrello E, Mauri V, Peri A, Gallo V, Auricchio F, Pietrabissa A: The clinical use of 3D printing in surgery. Updates Surg 2018, 70(3):381–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chepelev L, Wake N, Ryan J, Althobaity W, Gupta A, Arribas E, Santiago L, Ballard DH, Wang KC, Weadock W et al. : Radiological Society of North America (RSNA) 3D printing Special Interest Group (SIG): guidelines for medical 3D printing and appropriateness for clinical scenarios. 3D Print Med 2018, 4(1):11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ballard DH, Wake N, Witowski J, Rybicki FJ, Sheikh A: Radiological Society of North America (RSNA) 3D Printing Special Interest Group (SIG) clinical situations for which 3D printing is considered an appropriate representation or extension of data contained in a medical imaging examination: abdominal, hepatobiliary, and gastrointestinal conditions. 3D Print Med 2020, 6(1):13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim PS, Choi CH, Han IH, Lee JH, Choi HJ, Lee JI: Obtaining Informed Consent Using Patient Specific 3D Printing Cerebral Aneurysm Model. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 2019, 62(4):398–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zheng W, Chen C, Zhang C, Tao Z, Cai L: The Feasibility of 3D Printing Technology on the Treatment of Pilon Fracture and Its Effect on Doctor-Patient Communication. Biomed Res Int 2018, 2018:8054698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhuang YD, Zhou MC, Liu SC, Wu JF, Wang R, Chen CM: Effectiveness of personalized 3D printed models for patient education in degenerative lumbardisease. Patient Educ Couns 2019, 102(10):1875–1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang L, Shang XW, Fan JN, He ZX, Wang JJ, Liu M, Zhuang Y, Ye C: Application of 3D Printing in the Surgical Planning of Trimalleolar Fracture and Doctor-Patient Communication. Biomed Res Int 2016, 2016:2482086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goel V, Sawka CA, Thiel EC, Gort EH, O'Connor AM: Randomized trial of a patient decision aid for choice of surgical treatment for breast cancer. Med Decis Making 2001, 21(1):1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Festinger L: A theory of cognitive dissonance: Stanford University Press; 1957. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.