Abstract

Background

Electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy (ECG-LVH) is a common manifestation of preclinical cardiovascular disease. The present study aimed to investigate risk factors for ECG-LVH and its prevalence in a cohort of young Chinese individuals.

Methods

(1) A total of 1515 participants aged 36–45 years old from our previously established cohort who were followed up in 2017 were included. Cross-sectional analysis was used to examine risk factors for ECG-LVH and its prevalence. (2) A total of 235 participants were recruited from the same cohort in 2013 and were followed up in 2017. Longitudinal analysis was used to determine the predictors of LVH occurrence over the 4-year period. We used multivariable logistic regression models to calculate OR and 95% CIs and to analyze risk factors for ECG-LVH.

Results

In the cross-sectional analysis, the prevalence of LVH diagnosed by the Cornell voltage-duration product in the overall population and the hypertensive population was 4.6% and 8.8%, respectively. The logistic regression results shown that female sex [2.611 (1.591–4.583)], hypertension [2.638 (1.449–4.803)], systolic blood pressure (SBP) [1.021 (1.007–1.035)], serum uric acid (SUA) [1.004 (1.001–1.006)] and carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT) [67.670 (13.352–342.976)] were significantly associated with the risk of LVH (all P < 0.05). In the longitudinal analysis, fasting glucose [1.377 (1.087–1.754)], SBP [1.046 (1.013–1.080)] and female sex [1.242 (1.069–1.853)] were independent predictors for the occurrence of LVH in the fourth year of follow-up.

Conclusions

Our study suggested that female sex, hypertension, SBP, SUA and CIMT were significantly associated with the risk of LVH in young people. In addition, fasting glucose, SBP and female sex are independent predictors of the occurrence of LVH in a young Chinese general population.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12872-021-01966-y.

Keywords: Electrocardiogram, Cornell voltage-duration product, Risk factors, Left ventricular hypertrophy, Cohort study

Background

Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), as defined by electrocardiography (ECG) or echocardiographic criteria, is a potential independent predictor of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [1, 2]. The mechanism of LVH development is not fully understood, but hemodynamic factors, such as increased afterload and activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system in the context of hypertension [3, 4], are important for the development of LVH. Blood pressure is the strongest independent risk factor for LVH, and LVH has been observed in all stages of hypertension [5]. However, LVH can also be present in normotensive subjects, and the severity of hypertension is far from explaining the changes in left ventricular mass index (LVMI) [6]. Thus, nonhemodynamic mechanisms, such as metabolic factors and genetic factors, are likely to contribute to the development of LVH.

Nonhaemodynamic factors are likely to be involved in the pathogenesis of LVH, as increased blood pressure values explain less than 30% of variations in LVMI, both in normotensive and hypertensive subjects [7]. Some risk factors, such as age, sex [8], body mass index (BMI) [9], SUA [10], insulin resistance and diabetes mellitus [11, 12], may all play roles in the pathogenesis of LVH. However, in China and other countries, most studies on LVH have mainly select middle-aged and elderly patients with hypertension, with a large age range and a large number of complications [2, 4, 5, 8–12]. At present, there are no reports on the prevalence and related risk factors of LVH among young subjects in large population-based samples, especially in the rural young population of China. According to China Hypertension Survey 2012–2015 [13], among Chinese adults ≥ 18 years old, the overall crude prevalence of hypertension was 27.9%, and the weighted prevalence was 23.2%. The prevalence of hypertension among young people aged 18–24, 25–34 and 35–44 years old was 4.0%, 6.1% and 15.0%, respectively, which increased compared with the Chinese hypertension survey in 2002 [14], and the prevalence of LVH will continue to increase in the future. Therefore, it is of great significance to identify the prevalence and related risk factors of LVH in young subjects.

Therefore, we conducted cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses based on our previously established cohort to investigate related risk factors for ECG-LVH and its prevalence in a cohort of young Chinese individuals from the general population.

Methods

Subjects

The study population was derived from the Hanzhong Adolescent Hypertension Study, which was established in 1987. The Hanzhong Adolescent Hypertension Study is an ongoing prospective, population-based cohort study of 4623 Chinese adolescents who regularly undergo follow-ups to investigate the development of cardiovascular risk factors originating in children and young adults. Details of the study protocol have been published elsewhere [15–17].

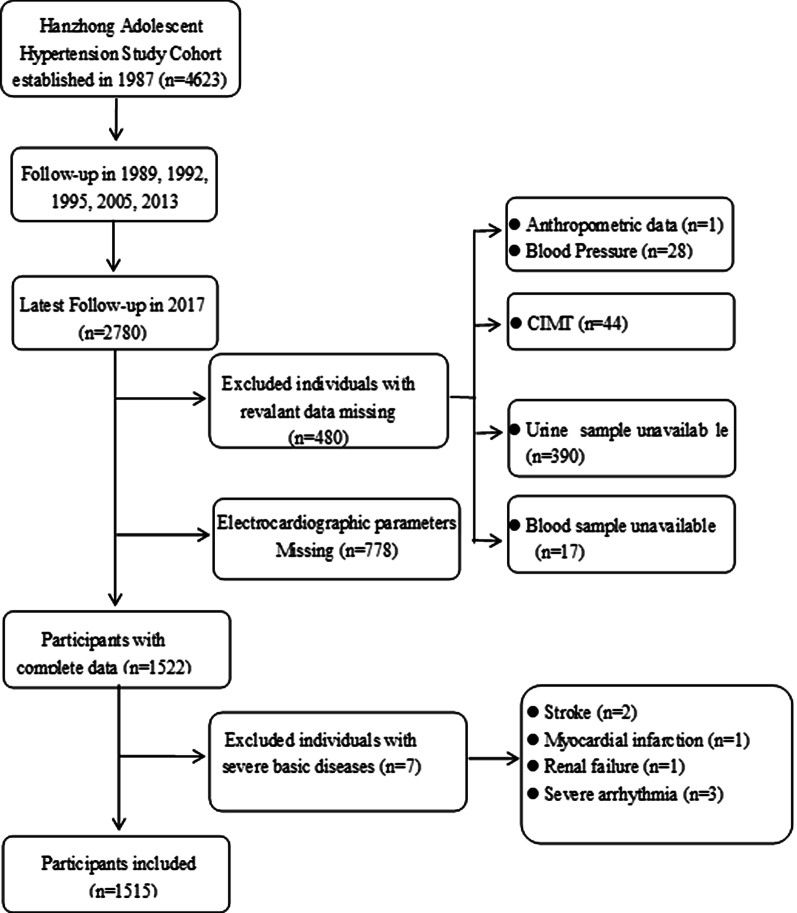

This study was divided into two sections: (1) In the cross-sectional analysis, we used data from the large cohort that was followed up in 2017. The participant selection process is described in Fig. 1. Participants were excluded if they had missing data on ECG parameters (n = 778), relevant measurement data (n = 480) and a self-identified history of stroke, coronary heart disease, renal failure or severe arrhythmia (n = 7), leaving 1515 subjects for the primary analyses. (2) In the longitudinal analysis, we used data from a small cohort of 338 subjects that was created based on the large cohort in 2005. The detailed study design and procedures have been published previously [17, 18]. We followed up with this small cohort in 2013 and 2017. For the current analysis, we did not measure ECG parameters or blood biochemical indicators in 2005, so the small cohort that was followed up in 2013 was considered the baseline for investigating risk factors for ECG-LVH. In 2013, we performed echocardiographic examination in this small cohort. Methods and criteria of echocardiographic LVH were described in detail elsewhere [12]. Participants who were lost to follow-up in 2013 and 2017 (n = 100) and those with echocardiographic LVH in 2013 (n = 3) were excluded. The remaining 235 subjects with complete data in 2013 and 2017 were included in the longitudinal analysis.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram for participants in cross-sectional study

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University, and written informed consent was obtained from each participant at each examination phase. The study complied with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration. Trial registration Number: NCT02734472. Date of registration: 12/04/2016.

Anthropometric measurements

Information on occupation, education, smoking habits, alcohol consumption, physical activity, medical conditions and medication use was collected using a self-administered questionnaire. Body weight and height were measured, and BMI was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height (m2). Blood pressure was measured with the participant in a seated position using a standard mercury sphygmomanometer as previously described [15, 19]. Hypertension was defined as a systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥ 140 mmHg or a diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥ 90 mmHg or the use of antihypertensive agents according to the subjects’ self-report or pharmacy data. Carotid intima-media thickness, defined as the distance from the intima-luminal interface to the media-adventitial interface, was measured as previously described [17]. Three images were obtained for both common carotid arteries, and the average of the six that were measured were used for analysis. The same sonographer who was blinded to the subjects’ clinical status carried out all the measurements.

Biochemical assays

Venous blood samples were obtained from all participants after a 12-h overnight fast. Standardized measurements for fasting glucose, serum total cholesterol, triglycerides, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), serum creatinine, SUA, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), urinary creatinine and albumin were performed in the clinical laboratory at the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University. Details of these assays have been described previously [15, 16, 18]. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the formula adapted from the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation on the basis of data from Chinese subjects with CKD [16, 20]. The urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (uACR) was calculated as urine albumin in mg divided by urine creatinine in mmol (mg/mmol).

Electrocardiographic measurements

According to the Minnesota code criteria, standard supine 12-lead electrocardiograms (ECGs) were recorded, and LVH was defined by the ECG Cornell voltage-duration product [RaVL + SV3 (adjusted by the addition of 8 mm for women) × QRS duration] > 2440 mm ms [21, 22], using the mean value of three consecutive measurements. Two observers performed measurements in duplicate with a graduated lens on standard 12-lead ECGs registered at a 25 mm/s speed and 10 mm/mV gain. The R wave amplitude in aVL and V5 and the S wave depth in V1 and V3 were measured as the distance (mm) between the isoelectric line and the nadir or zenith, respectively. The QRS duration was the average of three consecutive measurements of the QRS complexes. The QT interval and the QT interval duration corrected for the previous cardiac cycle length (QTc) were calculated as described in detail elsewhere [22]. Other ECG criteria, such as Sokolow-Lyon voltage, Sokolow-Lyon voltage-duration product and Cornell voltage criteria, were calculated according to the ECG parameters.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as medians (inter-quartile range) for non-normally distributed values, as the means ± standard deviations for normally distributed values, and as percentages. Significant differences between the groups were calculated using the Student’s t-test, the Mann–Whitney test and χ2-test as appropriate. The correlation coefficient r was measured to assess the relationship between two variables. We analyzed the association between related factors and LVH with logistic regression in cross-sectional analysis and longitudinal analyses. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 25.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of participants in the cross-sectional study

Table 1 presents the characteristics of all subjects according to LVH status. Among this young population, the average of Cornell voltage duration product criteria was 1201.45 ± 494.86 mm ms, and a total of 70 subjects had LVH according to Cornell voltage duration product criteria. The prevalence of LVH diagnosed by the Cornell voltage-duration product in the total population and the hypertensive population was 4.6% and 8.8%, respectively. The proportion of females and hypertension, BMI, waist-hip ratio (WHR), SBP, DBP, SUA, uACR and CIMT were higher in participants with LVH than in those without LVH. There were no statistically significant differences in age, heart rate, eGFR, blood lipids, fasting glucose and urinary uric acid/creatinine ratio (uUA/Cre) between the two groups.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants categorized by LVH status (n = 1515)

| Variable | ALL | Subjects with LVH | Non-LVH | P values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of subjects | 1515 | 70 | 1445 | – |

| Age, y | 43 (40, 45) | 43 (41, 45) | 43 (40, 45) | 0.493 |

| Female, no. (%) | 663(43.8) | 36 (51.4) | 627 (43.4) | 0.021 |

| BMI, Kg/m2 | 23.7 (21.8–25.8) | 25.2 (22.7–26.8) | 23.6 (21.8–25.8) | 0.004 |

| WHR | 0.92 (0.86–0.96) | 0.96 (0.89–0.99) | 0.92 (0.87–0.97) | 0.012 |

| Current smoking, no. (%) | 724 (47.8) | 30 (42.9) | 694 (48.0) | 0.453 |

| alcohol use, no. (%) | 474 (31.3) | 19 (27.1) | 455 (31.5) | 0.438 |

| Hypertension, no. (%) | 171 (11.3) | 15 (21.4) | 156 (10.8) | 0.002 |

| Diabetes mellitus, no. (%) | 103 (6.8) | 4 (5.7) | 99 (6.9) | 0.662 |

| SBP, mmHg | 121.0 (112.0–130.7) | 128.7 (114.7–138.8) | 120.0 (112.0–129.3) | 0.001 |

| DBP, mmHg | 75.3 (68.7–82.7) | 82.9 (72.9–89.4) | 75.3 (68.7–82.7) | < 0.001 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 73.0 (67.0–79.0) | 74.0 (67.8–83.0) | 73.0 (66.0–79.0) | 0.133 |

| SUA, μmol/L | 268.1 (210.7–323.1) | 280.3 (224.1–352.0) | 260.9 (205.1–320.6) | 0.043 |

| Serum creatinine, umol/L | 76.02 ± 14.56 | 74.78 ± 15.16 | 76.04 ± 14.55 | 0.473 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73m2 | 92.11 ± 26.07 | 88.60 ± 17.58 | 92.18 ± 26.20 | 0.255 |

| Fasting glucose, mmol/L | 4.57 (4.28–4.89) | 4.53 (4.20–4.93) | 4.57 (4.27–4.89) | 0.725 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 4.51 (4.04–5.00) | 4.60 (4.02–4.99) | 4.50 (4.04–5.00) | 0.962 |

| Triglycerides, mmol/L | 1.36 (0.95–1.91) | 1.41 (0.97–1.86) | 1.35 (0.95–1.91) | 0.860 |

| LDL-C, mmol/L | 2.51 (2.14–2.89) | 2.50 (2.04–2.95) | 2.50 (2.14–2.89) | 0.710 |

| HDL-C, mmol/L | 1.15 (0.99–1.33) | 1.15 (1.00–1.31) | 1.15 (0.99–1.33) | 0.911 |

| uUA/Cre | 0.19 (0.10–0.32) | 0.22 (0.13–0.41) | 0.19 (0.11–0.32) | 0.069 |

| UACR, mg/g | 8.30 (5.45–14.42) | 10.90 (7.09–24.83) | 8.26 (5.39–14.21) | 0.001 |

| hs-CRP, mg/L | 0.31 (0.15–0.74) | 0.32 (0.15–0.77) | 0.30 (0.15–0.75) | 0.847 |

| CIMT, mm | 0.62 (0.53–0.75) | 0.74 (0.60–0.83) | 0.62 (0.53–0.75) | < 0.001 |

| Cornell index, mm ms | 1201.45 ± 494.86 | 3010.62 ± 665.11 | 1167.40 ± 422.50 | < 0.001 |

Normally distributed variables are expressed as mean ± SD as determined by the Student’s t-test, non-normally distributed variables are expressed as medians (inter-quartile range) as determined by Mann–Whitney test, categorical variables are expressed as numbers and percentages by χ2-test

BMI body mass index, WHR waist hip rate, SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, SUA serum uric acid, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, LDL-C low-density lipoprotein, HDL-C high-density lipoprotein, uUA/Cre urinary uric acid/creatinine ratio, uACR urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio, hs-CRP high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, CIMT carotid intima-media thickness

Additional file 1: Table S1 presents the ECG parameters of all subjects according to LVH status. Sokolow-Lyon voltage, Sokolow-Lyon voltage duration product, Cornell voltage criteria, Cornell voltage duration product, QRS duration and QTc were higher in participants with LVH than in those without LVH.

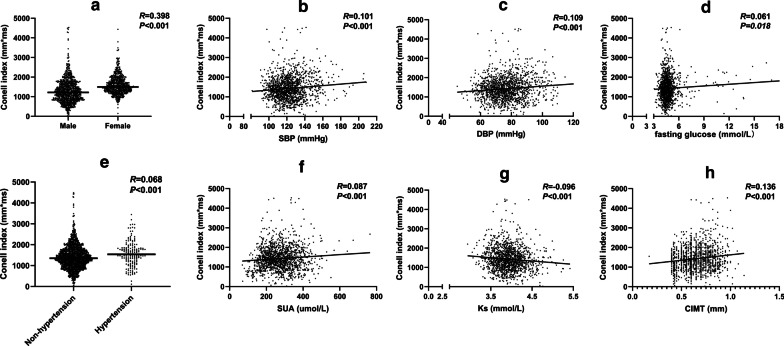

Associations of various characteristics with Cornell index

The correlation analyses showed that Cornell index was positively correlated with female sex (r = 0.398, P < 0.001) and hypertension (r = 0.068, P < 0.001), SBP (r = 0.101, P < 0.001) and DBP (r = 0.109, P < 0.001). In addition, LVH was also associated with fasting glucose (r = 0.061, P = 0.018), SUA (r = 0.087, P < 0.001) and CIMT (r = 0.136, P < 0.001), while it was inversely associated with serum potassium (r = -0.096, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Relationship between various characteristics and Cornell index by correlation analysis. R, correlation coefficient. DBP diastolic blood pressure, Ks serum potassium, CIMT Carotid intima-media thickness, SBP systolic blood pressure, SUA serum uric acid

To further comprehensively and accurately investigate this finding, we analyzed the relationship between various characteristics and LVH based on logistic regression in a cross-sectional study. We found that female sex [2.611 (1.591–4.583)], hypertension [2.638 (1.449–4.803)], SBP [1.021 (1.007–1.035)], SUA [1.004 (1.001–1.006)] and CIMT [67.670 (13.352–342.976)] were significantly associated with LVH (all P < 0.05) (Table 2). DBP (P = 0.114), BMI (P = 0.537), WHR (P = 0.430), fasting glucose (P = 0.198) and serum potassium (P = 0.215) did not remain significant in the model. To exclude the effect of collinearity between variables on the results, we performed a collinearity diagnosis of variables using variance inflation factor (VIF) values. As the results are shown, we can consider that there is no collinearity between the variables (Additional file 1: Table S2).

Table 2.

Association between various characteristics and the risk of LVH by logistic regression analysis (n = 1515)

| Variable | Odds ratios (confidence interval) | P values |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (female) | 2.611 (1.591–4.583) | < 0.001 |

| Age, y | 1.002 (0.917–1.094) | 0.969 |

| Hypertension | 2.638 (1.449–4.803) | 0.005 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.880 (0.249–3.116) | 0.843 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 1.029 (0.939–1.128) | 0.537 |

| WHR | 5.431 (0.081–364.747) | 0.430 |

| SBP, mmHg | 1.021 (1.007–1.035) | 0.003 |

| DBP, mmHg | 1.014 (0.997–1.032) | 0.114 |

| Fasting glucose, mmol/L | 1.114 (0.945–1.313) | 0.198 |

| Serum potassium, mmol/L | 0.614 (0.285–1.326) | 0.215 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73m2 | 0.999 (0.989–1.010) | 0.878 |

| SUA, umol/L | 1.004 (1.001–1.006) | 0.013 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 0.685 (0.230–2.040) | 0.497 |

| Triglycerides, mmol/L | 1.061 (0.678–1.659) | 0.796 |

| LDL-C, mmol/L | 1.029 (0.309–3.426) | 0.963 |

| HDL-C, mmol/L | 3.869 (0.664–22.557) | 0.133 |

| CIMT, mm | 67.670 (13.352–342.976) | < 0.001 |

Logistic regression analyses were used to test the risk of LVH. Age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, smoking status, alcohol consumption, BMI, WHR, SBP, DBP, fasting glucose, SUA, eGFR, total cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL-C, HDL-C, uUA/Cre and CIMT were all included in the model

To extend this finding to clinical practice, we further investigated the association between various characteristics and LVH based on logistic regressions in normotensive subjects (n = 1344). Female sex [1.366 (1.210–1.636)], SBP [1.017 (1.003–1.031)], SUA [1.003 (1.001–1.006)] and CIMT [47.068 (7.946–278.798)] were still significantly associated with LVH (Additional file 1: Table S3).

Participant characteristics in the longitudinal study

The characteristics of those who participated in both surveys are presented in Table 3. Subjects had higher WHR, heart rate, serum creatinine, fasting glucose, total cholesterol, LDL-C, uACR and CIMT; lower DBP, SUA and HDL-C levels; and a higher proportion of alcohol consumption and diabetes after a 4-year follow-up. There were no statistically significant differences in BMI, hypertension rate, SBP, eGFR or triglycerides between baseline and follow-up. In the fourth year of follow-up, there were 26 subjects with new-onset LVH.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the study participants at baseline and follow-up (n = 235)

| Variable | Baseline in 2013 | Follow-up in 2017 | P values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female, no. (%) | 104 (44.2) | 104 (44.2) | – |

| Age, years | 39 (36, 41) | 43 (40, 45) | < 0.001 |

| Current smoking, no. (%) | 110 (41.5) | 105 (44.6) | 0.489 |

| Alcohol use, no. (%) | 23 (9.1) | 65 (27.8) | < 0.001 |

| BMI, Kg/m2 | 23.83 (21.63–26.33) | 23.73 (22.19–25.92) | 0.826 |

| WHR | 0.90 (0.85–0.95) | 0.93 (0.87–0.97) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension, no. (%) | 79 (29.7) | 53 (22.6) | 0.792 |

| Diabetes mellitus, no. (%) | 6 (2.3) | 15 (6.2) | 0.023 |

| SBP, mmHg | 120.7 (111.3–132.0) | 121.0 (112.8–131.7) | 0.403 |

| DBP, mmHg | 80.0 (72.7–89.0) | 76.3 (69.3–84.8) | 0.001 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 70.0 (66.0–80.0) | 74.0 (67.0–81.0) | 0.022 |

| SUA, μmol/L | 300.9 (246.0–369.7) | 267.9 (209.7–335.8) | < 0.001 |

| Serum creatinine, umol/L | 74.21 ± 14.02 | 80.82 ± 17.69 | < 0.001 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73m2 | 94.90 ± 21.13 | 94.12 ± 26.23 | 0.694 |

| Fasting glucose, mmol/L | 4.58 (4.26–4.92) | 5.00 (4.69–5.41) | < 0.001 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 4.27 (3.83–4.72) | 4.51 (4.07–4.99) | < 0.001 |

| Triglycerides, mmol/L | 1.42 (1.00–2.07) | 1.37 (0.98–1.96) | 0.405 |

| LDL-C, mmol/L | 2.33 (2.00–2.70) | 2.51 (2.14–2.89) | 0.001 |

| HDL-C, mmol/L | 1.66 (1.43–1.87) | 1.14 (1.01–1.32) | < 0.001 |

| UACR, mg/g | 6.07 (4.08–10.72) | 8.80 (5.77–15.17) | < 0.001 |

| CIMT, mm | 0.50 (0.40–0.60) | 0.64 (0.55–0.74) | < 0.001 |

| LVH, no. (%) | – | 26 (11.0) | – |

BMI body mass index, WHR waist hip rate, SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, SUA serum uric acid, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, LDL-C low-density lipoprotein, HDL-C high-density lipoprotein, uACR Urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio, CIMT carotid intima-media thickness

Predictors of LVH in the fourth year of follow-up

Traditional risk factors at baseline in regard to LVH in the fourth year of follow-up in logistic regression analysis are shown in Table 4. Three factors were identified in the binary logistic regression analysis as predictors of fourth-year LVH. These factors were fasting glucose [1.377 (1.087–1.754)], SBP [1.046 (1.013–1.080)] and female sex [1.242 (1.069–1.853)].

Table 4.

Independent predictors of left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) in the fourth year in logistic regression analysis (n = 235)

| Baseline characteristic | Odds ratios (confidence interval) | P values |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (female) | 1.242 (1.069–1.853) | 0.043 |

| Age, y | 0.872 (0.675–1.126) | 0.293 |

| Hypertension | 0.242 (0.041–1.418) | 0.116 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.810 (0.07–1.874) | 0.054 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 1.042 (0.821–1.323) | 0.736 |

| WHR | 6.321 (0.012–34.795) | 0.194 |

| SBP, mmHg | 1.046 (1.013–1.080) | 0.006 |

| DBP, mmHg | 0.979 (0.883–1.084) | 0.678 |

| Fasting glucose, mmol/L | 1.377 (1.087–1.754) | 0.008 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73m2 | 0.981 (0.948–1.017) | 0.298 |

| SUA, umol/L | 0.991 (0.980–1.002) | 0.100 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 2.118 (0.058–7.240) | 0.683 |

| Triglycerides, mmol/L | 0.828 (0.4.4–1.695) | 0.605 |

| LDL-C, mmol/L | 0.267 (0.004–1.704) | 0.534 |

| HDL-C, mmol/L | 0.313 (0.006–15.257) | 0.558 |

| CIMT, mm | 97.040 (0.081–1156.760) | 0.205 |

Logistic regression analyses were used to test the independent predictors of LVH, age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, BMI, WHR, SBP, DBP, fasting glucose, SUA, eGFR, total cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL-C, HDL-C and CIMT were all included in the model

Discussion

Electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy is a common manifestation of preclinical cardiovascular disease. Nonhaemodynamic factors are likely to be involved in the pathogenesis of LVH, and the severity of hypertension is far from explaining the changes in left ventricular mass. With this prospective cohort study, we were the first to investigate risk factors for ECG-LVH and its prevalence in a cohort of young Chinese individuals. We found that the prevalence of LVH diagnosed by the Cornell voltage-duration product in the overall population and the hypertensive population was 4.6% and 8.8%, respectively. Our study suggested that female sex, hypertension, SBP, SUA and CIMT were significantly associated with the risk of LVH in young people. In addition, fasting glucose, SBP and female sex are independent predictors of the occurrence of LVH in a young Chinese general population.

LVH appears to be highly prevalent in individuals with hypertension but also in the general population. Currently, there are no large epidemiological studies on the LVH detection rate and its risk factors in young Chinese populations. Several previous studies have investigated the prevalence of LVH in the general population. For example, Joji Ishikawa et al. [23] found that in 10,755 individuals from the general Japanese population, the detection rate of LVH diagnosed by the Cornell voltage-duration product was 6.4% in all subjects and 11.0% in the hypertension subgroup. Lehtonen AO et al. [24] found that the LVH detection rates according to the Cornell voltage criteria in individuals with normal blood pressure, hypertension grade 1 and hypertension grade 2 among the 5800 Finnish population were 5.1%, 9.0% and 13.1%, respectively. In line with these two studies, we found that the prevalence of LVH diagnosed by the Cornell voltage-duration product in the total young population and hypertensive population were 4.6% and 8.8%, respectively.

Currently, the mechanism of LVH development is not completely clear, except for hemodynamics, and its pathogenesis is related to age, sex, body mass, race, genetic factors, metabolic status (such as insulin resistance and hyperuricemia) and other factors [8–12]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate risk factors for ECG-LVH in a cohort of young Chinese individuals from the general population. We observed that fasting glucose, SBP and female sex are independent predictors of the occurrence of LVH in the fourth year of follow-up. Female, higher fasting glucose and SBP can increase the risk of LVH. Blood pressure is the strongest independent risk factor for LVH, and that approximately 30% of hypertensive patients may have LVH, and the detection rate of LVH is positively correlated with the severity of hypertension. [24] Blood glucose is closely associated with insulin levels, and increased glucose levels may cause hyperinsulinemia. Our observation is similar to that of Lin et al., who observed that baseline fasting glucose is correlated with the 4-year change in LVMI and is an independent predictor for LVMI and the occurrence of LVH after a 4-year follow-up in normotensive healthy elderly subjects without diabetes mellitus [25].Insulin itself could induce cardiovascular hypertrophy by acting on insulin growth factor receptors and simulating cell proliferation and lipid deposition [26, 27]. In addition, our results showed that SUA and CIMT were significantly associated with the risk of LVH in young people.

Yoshio Iwashima et al. [28] showed that SUA is independently associated with LVMI and suggest that hyperuricemia combined with LVH is an independent and powerful predictor for Cardiovascular disease in asymptomatic subjects with essential hypertension. In line with this study, we found that SUA was significantly associated with LVH in correlation and logistic regression analyses in this Chinese cohort. In addition, many studies have shown that SUA may impair NO generation, induce endothelial dysfunction, and promote oxidative metabolism and smooth muscle cell proliferation [28, 29], which are known to induce cardiac hypertrophy. These results suggest that cardiac hypertrophy may be partially attributable to an increase in UA itself. Similar to what we found, Nam-ho Kim et al. [30] conducted a cross-sectional study with 9266 middle-aged and elderly individuals from the general populations in Korea and found that compared with other quartile groups, the risk of LVH increased by 48% in the highest quartile of CIMT. Carotid IMT thickening was associated with the presence of endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, inflammatory mediators and metabolic factors, which can lead to myocardial collagen hyperplasia and fibrosis aggravation and may thereby promote LVH [30, 31].

In our study, we also found that sex was significantly associated with LVH in the young population. Numerous studies have confirmed that there are sex differences in LVH, and the prevalence of LVH in females was higher than that in males, regardless of the use of ECG or echocardiography. A retrospective analysis of 30 studies showed that the prevalence of LVH diagnosed by ECG in hypertensive patients was 35.6%-40.9%, among which the detection rates were 36.0%-43.5% in males and 37.9%-46.2% in females [32]. A study also showed that the prevalence of LVH in Chinese hypertension patients diagnosed by echocardiography was significantly higher in females than in males [33]. Currently, the mechanism of the correlation between sex and LVH has not been fully elucidated but may be related to ECG diagnostic methods [21, 22], sex differences in the size and mass of the left ventricle and its response to chronic pressure load [34, 35], and sex hormones factors [35].

Some limitations of our study merit consideration. First, our results were obtained from young northern Chinese individuals and consequently may not be generalizable to other age and ethnic groups with different demographics. Second, we used electrocardiograms to diagnose LVH at the follow-up in 2017 and failed to conduct echocardiography. Echocardiographic detection of LVH provides more accurate estimates of LVMI than ECGs. Although echocardiography is the preferred method to diagnose LVH in clinical practice, ECGs are commonly used as the first-line instrument for detecting LVH due to its convenience, cost-effectiveness, good reproducibility and availability in large cohort settings. Finally, some participants were lost during the follow-up period, and the number of subjects with LVH during the follow-up period was relatively small. However, as we know, the subjects of this study are young individuals from the general population who are currently in the period of subclinical target organ damage, and the prevalence of hypertension and cardiovascular disease is relatively low. Clarifying the risk factors for Cardiovascular disease in young populations is of great significance for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease, and we will continue to follow up.

In conclusion, our study shows female sex, hypertension, SBP, SUA and CIMT were significantly associated with the risk of LVH in the young Chinese population. AND fasting glucose, SBP and female sex are independent predictors of the occurrence of LVH in the fourth year of follow-up. Our study suggests that, even in an apparently healthy, relatively young population, in addition to the active control of blood pressure, regular monitoring of SUA and fasting glucose and the lowering of UA and glucose if necessary, may be actively considered to reduce the risk of left ventricular hypertrophy.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.: Table S1. ECG parameters of participants categorized by LVH status (n=1515). Table S2. The collinearity diagnosis analysis between variables (n=1515). Table S3. Association between various characteristics and the risk of LVH by multiple logistic regression analysis in normotensive subjects (n=1344).

Acknowledgements

The Hanzhong Adolescent Hypertension Study is a joint effort of many investigators and staff members whose contribution is gratefully acknowledged. We especially thank the children and adults who have participated in this study over many years.

Abbreviations

- BMI

Body mass index

- CIMT

Carotid intima-media thickness

- ECG-LVH

Electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy

- eGFR

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- HDL-C

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- hs-CRP

High-sensitivity C-reactive protein

- LVH

Left ventricular hypertrophy

- LDL-C

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LVMI

Left ventricular mass index

- SBP

Systolic blood pressure

- SUA

Serum uric acid

- uACR

Urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio

- WHR

Waist-hip ratio

Authors' contributions

Study conception and design was performed by JJM, YYL and KG. Data collection was performed by YYL, QM, CC, YY, YW, WLZ, JWH, KKW, YS, CC. Analysis was performed by YYL, KG, BWF, LY, WJZ. Writing was performed by YYL, KG, and JJM. This manuscript was read and approved by all credited authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China No. 81870319 (J.-J.M.) and No. 81700368 (C.C.), Grant 2017YFC1307604 from the Major Chronic Non-communicable Disease Prevention and Control Research Key Project of the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China, the Clinical Research Award of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaoton University (XJTU1AF-CRF-2019-004), and Grant 2017ZDXM-SF-107 from the Key Research Project of Shaanxi Province. National Key R&D Program of China(2016YFC1300104).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due the ongoing nature of this study, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University, and written informed consent was obtained from each participant at each examination phase. The study complied with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration. Trial registration Number: NCT02734472. Date of registration: 12/04/2016.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there is no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yue-Yuan Liao and Ke Gao have contributed equally to this work

References

- 1.Vakili BA, Okin PM, Devereux RB. Prognostic implications of left ventricular hypertrophy. Am Heart J. 2001;141(3):334–341. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.113218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koren MJ, Devereux RB, Casale PN, Savage DD, Laragh JH. Relation of left ventricular mass and geometry to morbidity and mortality in uncomplicated essential hypertension. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114(5):345–352. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-114-5-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mancia G, Carugo S, Grassi G, Lanzarotti A, Schiavina R, Cesana G, et al. Prevalence of left ventricular hypertrophy in hypertensive patients without and with blood pressure control: data from the PAMELA population. PressioniArterioseMonitorate E LoroAssociazioni. Hypertension. 2002;39(3):744–749. doi: 10.1161/hy0302.104669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dahlof B. Left ventricular hypertrophy and angiotensin II antagonists. Am J Hypertens. 2001;14(2):174–182. doi: 10.1016/S0895-7061(00)01257-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunn FG, McLenachan J, Isles CG, Brown I, Dargie HJ, Lever AF, et al. Left ventricular hypertrophy and mortality in hypertension: an analysis of data from the Glasgow Blood Pressure Clinic. J Hypertens. 1990;8(8):775–782. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199008000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rowlands DB, Glover DR, Ireland MA, McLeay RA, Stallard TJ, Watson RD, et al. Assessment of left-ventricular mass and its response to antihypertensive treatment. Lancet. 1982;1(8270):467–470. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(82)91448-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lorell BH, Carabello BA. Left ventricular hypertrophy: pathogenesis, detection, and prognosis. Circulation. 2000;102(4):470–479. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.102.4.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gardin JM, Siscovick D, Anton-Culver H, Lynch JC, Smith VE, Klopfenstein HS, et al. Sex, age, and disease affect echocardiographic left ventricular mass and systolic function in the free-living elderly. Cardiovas Health Study Circ. 1995;91(6):1739–1748. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.6.1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bombelli M, Facchetti R, Sega R, Carugo S, Fodri D, Brambilla G, et al. Impact of body mass index and waist circumference on the long-term risk of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and cardiac organ damage. Hypertension. 2011;58(6):1029–1035. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.175125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Viazzi F, Parodi D, Leoncini G, Parodi A, Falqui V, Ratto E, et al. Serum uric acid and target organ damage in primary hypertension. Hypertension. 2005;45(5):991–996. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000161184.10873.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lind L, Andersson PE, Andren B, Hanni A, Lithell HO. Left ventricular hypertrophy in hypertension is associated with the insulin resistance metabolic syndrome. J Hypertens. 1995;13(4):433–438. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199504000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li T, Chen S, Guo X, Yang J, Sun Y. Impact of hypertension with or without diabetes on left ventricular remodeling in rural Chinese population: a cross-sectional study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2017;17(1):206. doi: 10.1186/s12872-017-0642-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Z, Chen Z, Zhang L, Wang X, Hao G, Zhang Z, et al. Status of Hypertension in China: results From the China Hypertension Survey, 2012–2015. Circulation. 2018;137(22):2344–2356. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu Y, Huxley R, Li L, Anna V, Xie G, Yao C, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in China: data from the China National Nutrition and Health Survey 2002. Circulation. 2008;118(25):2679–2686. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.788166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Y, Hu JW, Qu PF, Wang KK, Yan Y, Chu C, et al. Association between urinary sodium excretion and uric acid, and its interaction on the risk of prehypertension among Chinese young adults. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):7749. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-26148-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zheng W, Mu J, Chu C, Hu J, Yan Y, Ma Q, et al. Association of blood pressure trajectories in early life with subclinical renal damage in middle age. J Am SocNephrol. 2018;29(12):2835–2846. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2018030263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y, Yuan Y, Gao WH, Yan Y, Wang KK, Qu PF, et al. Predictors for progressions of brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity and carotid intima-media thickness over a 12-year follow-up: Hanzhong Adolescent Hypertension Study. J Hypertens. 2019;37(6):1167–1175. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000002020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Y, Lv YB, Chu C, Wang M, Xie BQ, Wang L, et al. Plasma renalase is not associated with blood pressure and brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity in Chinese adults with normal renal function. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2016;41(6):837–847. doi: 10.1159/000452587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Y, Chu C, Wang KK, Hu JW, Yan Y, Lv YB, et al. Effect of salt intake on plasma and urinary uric acid levels in chinese adults: an interventional trial. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):1434. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-20048-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma YC, Zuo L, Chen JH, Luo Q, Yu XQ, Li Y, et al. Modified glomerular filtration rate estimating equation for Chinese patients with chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(10):2937–2944. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006040368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okin PM, Devereux RB, Jern S, Julius S, Kjeldsen SE, Dahlof B. Relation of echocardiographic left ventricular mass and hypertrophy to persistent electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy in hypertensive patients: the LIFE Study. Am J Hypertens. 2001;14(8 Pt 1):775–782. doi: 10.1016/S0895-7061(01)01291-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruno G, Giunti S, Bargero G, Ferrero S, Pagano G, Perin PC. Sex-differences in prevalence of electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy in Type 2 diabetes: the Casale Monferrato Study. Diabetic Med. 2004;21(8):823–828. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2004.01246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ishikawa J, Ishikawa S, Kabutoya T, Gotoh T, Kayaba K, Schwartz JE, et al. Cornell product left ventricular hypertrophy in electrocardiogram and the risk of stroke in a general population. Hypertension. 2009;53(1):28–34. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.118026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lehtonen AO, Puukka P, Varis J, Porthan K, Tikkanen JT, Nieminen MS, et al. Prevalence and prognosis of ECG abnormalities in normotensive and hypertensive individuals. J Hypertens. 2016;34(5):959–966. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin TH, Chiu HC, Su HM, Voon WC, Liu HW, Lai WT, et al. Association between fasting plasma glucose and left ventricular mass and left ventricular hypertrophy over 4 years in a healthy population aged 60 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(5):717–724. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rutter MK, Parise H, Benjamin EJ, Levy D, Larson MG, Meigs JB, et al. Impact of glucose intolerance and insulin resistance on cardiac structure and function: sex-related differences in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2003;107(3):448–454. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000045671.62860.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohya Y, Abe I, Fujii K, Ohmori S, Onaka U, Kobayashi K, et al. Hyperinsulinemia and left ventricular geometry in a work-site population in Japan. Hypertension. 1996;27(3 Pt 2):729–734. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.27.3.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iwashima Y, Horio T, Kamide K, Rakugi H, Ogihara T, Kawano Y. Uric acid, left ventricular mass index, and risk of cardiovascular disease in essential hypertension. Hypertension. 2006;47(2):195–202. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000200033.14574.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khosla UM, Zharikov S, Finch JL, Nakagawa T, Roncal C, Mu W, et al. Hyperuricemia induces endothelial dysfunction. Kidney Int. 2005;67(5):1739–1742. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim NH, Shin MH, Kweon SS, Ko JS, Lee YH. Carotid Atherosclerosis and electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy in the general population: the Namwon study. Chonnam Med J. 2017;53(2):153–160. doi: 10.4068/cmj.2017.53.2.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vaudo G, Schillaci G, Evangelista F, Pasqualini L, Verdecchia P, Mannarino E. Arterial wall thickening at different sites and its association with left ventricular hypertrophy in newly diagnosed essential hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2000;13(4 Pt 1):324–331. doi: 10.1016/S0895-7061(99)00229-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cuspidi C, Sala C, Negri F, Mancia G, Morganti A. Prevalence of left-ventricular hypertrophy in hypertension: an updated review of echocardiographic studies. J Hum Hypertens. 2012;26(6):343–349. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2011.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li H, Pei F, Shao L, Chen J, Sun K, Zhang X, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of abnormal left ventricular geometrical patterns in untreated hypertensive patients. BMC CardiovascDisord. 2014;66:14136. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-14-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carroll JD, Carroll EP, Feldman T, Ward DM, Lang RM, McGaughey D, et al. Sex-associated differences in left ventricular function in aortic stenosis of the elderly. Circulation. 1992;86(4):1099–1107. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.86.4.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petrov G, Regitz-Zagrosek V, Lehmkuhl E, Krabatsch T, Dunkel A, Dandel M, et al. Regression of myocardial hypertrophy after aortic valve replacement: faster in women? Circulation. 2010;122(11 Suppl):S23–28. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.927764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1.: Table S1. ECG parameters of participants categorized by LVH status (n=1515). Table S2. The collinearity diagnosis analysis between variables (n=1515). Table S3. Association between various characteristics and the risk of LVH by multiple logistic regression analysis in normotensive subjects (n=1344).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due the ongoing nature of this study, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.