Abstract

Purpose of Review:

Although healthcare providers are increasingly interested in addressing their female patient’s sexual wellbeing in a holistic fashion, most do not receive training in how to conceptualize the complex interactions between mind, body and spirit that drive health and wellness, let alone how to apply empirical data in any of these dimensions to their individual patients. Here, we present a simple mind-body-spirit model, grounded in an integrative medicine approach, to help translate research on sexual functioning and satisfaction into a shared decision-making plan for the management and enhancement of women’s sexual wellness.

Recent Findings:

In considering the dimensions of physical and behavioral health, spirituality and sensuality, physicians can help women orient to the ways in which their sexual healthcare can address their core values and connection to others, which in turn can improve sexual satisfaction. The application of the model is outlined in a case study.

Summary:

Too often female sexual wellbeing is not discussed in the medical setting and this mind-body-spirit model is a tool that health care providers could use address this important aspect of well-being.

Keywords: sexual function, sexual satisfaction, wellbeing, integrative medicine, holistic, women’s sexual health, spirituality

Introduction

“Wellness” is rapidly becoming a popular buzz word within the practice of medicine. Health care providers are incorporating wellness into many aspects within their practice. However, sexual wellbeing is an important dimension of wellness that is often overlooked by health care providers. Research shows that providers frequently do not directly ask about sexual health because of time constraints, their discomfort level with the topic and perceptions of patient discomfort disclosing this information (1, 2). This is especially true for female patients who are often not asked about sexual health nor sexual pleasure, let alone the ways in which sexuality impacts their mental, physical and spiritual health.

To assist providers who may have had limited training in addressing sexuality in their practice of medicine, several professional groups have created process of care documents for identification (3) and treatment (4, 5) of common sexual dysfunctions such as low sexual desire. However, even these expert documents do not often address dimensions of wellness that are important to holistic health, such as spirituality and sensuality. Possibly, this reflects attitudes that such factors are outside the scope of medical practice, despite strong evidence that they are strongly predictive of women’s sexual behaviors (6, 7) and sexual desire and fantasy (8, 9). Similarly, there is evidence that integrative health approaches that incorporate multiple dimensions of care are associated with patient-perceived benefit, satisfaction and value (10).

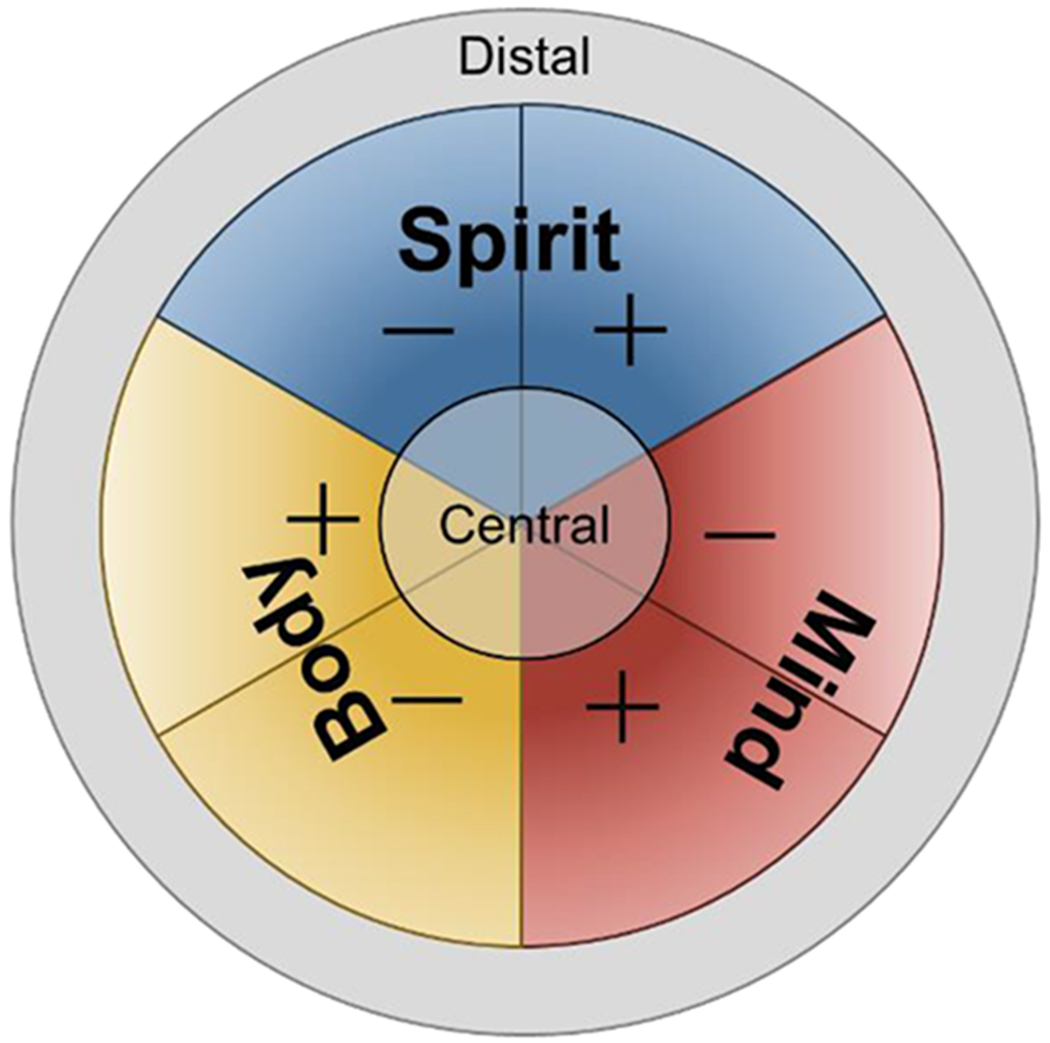

However, it is also possible that providers simply lack an organizing framework to conceptualize the holistic dimensions of their patient’s sexual wellbeing. To help bridge this gap, we present the mind-body-spirit model of female sexual wellbeing (Fig. 1), a simple framework grounded in the principles of integrative medicine: emphasizing wellness and healing of the whole person across biological, psychological and spiritual dimensions, and considering these dimensions equally important as patients and providers as they engage in a shared decision making process (11). The mind-body-spirit dimensions are thus represented equally in the model, reflecting their fundamental relationship in balance.

Figure 1.

The mind-body-spirit model of sexual wellbeing

Core and values positive and negative components in sexual wellbeing

Each domain – mind, body, and spirit – is presented with both positive and negative components. While many other models of sexual functioning include positive and negative factors (e.g., the Dual Control Model (12), the Sexual Tipping Point model (13)), these generally refer to factors that increase excitation vs. inhibition of sexual response. In our model, however, “positive” and “negative” refer consider how these factors may contribute to the patient’s broader health and wellbeing – how that dimension contributes to or interferes with the patient’s mental and physical health, and sexual and personal satisfaction, by shaping how the patient lives in or out of alignment with their own core values. In other words, a factor is considered positive if it makes it easier for the patient to express and explore their sexual interests and experience pleasure in ways that match their core values. Focusing on the patient’s core values as a foundation for their health and wellness has been shown to improve care outcomes across a range of medical conditions, including chronic pain, depression, substance use disorders, diabetes, obesity, and cancer (14, 15). In terms of sexual wellness, these core values are highly individualized and can include sexual pleasure, novelty and fun; intimacy and connection to self, others, or a higher being; power and empowerment; sense of identity and purpose in life; satisfaction from role fulfillment; or something else entirely. Part of the work of the integrative team, then, is drawing these core values out as the patient and provider consider treatment options.

Central aspects of sexual wellbeing

Also included in our model are central and distal aspects. Central aspects operate as the foundation for the rest of the dimension: they are core to how that dimension has an impact on the patient’s sexual wellbeing. Because central aspects are not usually easily visible from a surface survey of the patient’s presentation, they are rarely the immediate focus for treatment in routine care. However, when care does tap into these central aspects, the changes that are made tend to be the deepest and have the longest-lasting impact on the patient’s overall sexual wellbeing. Below, we consider central aspects for mind, body and spirit.

Central mental factors relating to women’s sexual wellbeing

Schema are mental frameworks we use to decide what to attend to, how to interpret and organize information, and guide our emotional and behavioral responses to that information (16, 17). Schema stem from our early life experiences and internalized attitudes and beliefs (16, 17), but can be updated throughout the lifespan in response to major life events (particularly trauma (18)) or in response to targeted psychotherapies such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (19, 20). In a psychologically healthy and resilient person, schema are useful heuristics that help guide our actions in ways that flexibly respond to the environment and resolve challenges. However, when schema become inflexible or distorted, they can lead to maladaptive patterns of thinking, feeling and acting – in other words, maladaptive schema can be a significant contributing factor in causing or maintaining both mental and physical illnesses (21).

Sexual self-schema, then, are the networks of beliefs and emotional biases that guide how we feel about ourselves as sexual beings and how we relate to others sexually, which unconsciously directs our sexual behaviors. Sexual self-schema can be broadly positive (emphasizing intimacy, passion, open and direct communication of needs, pleasure and fun) or broadly negative (emphasizing sexual shame or guilt, fear and avoidance, low body esteem) (16, 17). Negative sexual self-schema have been shown to be a major contributing factor to female sexual dysfunction (17). In turn, shifting one’s sexual self-schema in a positive direction has been shown to improve sexual functioning. For example, in two studies, when women with a history of childhood sexual abuse did five sessions of expressive writing focusing on their sexual self-schema, there were lasting improvements in sexual desire, arousal and orgasm function (19, 20). The guided prompts for this intervention are listed here: https://bit.ly/3bTymhu: patients can be directed to use these prompts for their own self-exploration of their sexual schema in between clinic visits.

Another central mental factor important for women’s sexual wellbeing is their type of sexual desire response. Although sexual desire has traditionally been understood as a drive similar to hunger or thirst, which appears spontaneously (that is, without preemptive cues), more recent research suggests that for many women (and indeed, some men), sexual desire is experienced as responsive (22, 23). Responsive sexual desire tends to be triggered by attention to sexual stimuli (such as spending time with an attractive partner), and may be noticed well after physiological sexual arousal processes have begun (24). Moreover, unlike a true drive – which grows in strength in proportion to the time since it was last sated, and is quickly quenched when its object is achieved – responsive desire may ebb and flow in a non-linear fashion, sometimes staying high despite high levels of sexual activity, and sometimes quite low despite long periods of abstinence. In fact, there is some evidence that, for women, sexual activity itself (and anticipation of sexual activity) may increase testosterone and other hormones that may promote further sexual desire (25). In other words, engaging with the target of sexual desire – that is, sexual activity – may increase responsive desire, not sate it.

Some research suggests that women are more likely to experience responsive desire; however, common perceptions of “healthy” desire are modeled on spontaneous desire (22). This means that many women many feel dysfunctional because their desire does not match the story they are told about how their desire is “supposed” to operate; indeed, a high proportion of women who report responsive desire are classified as “sexually dysfunctional” by clinical instruments that presuppose a linear, spontaneous model (27). In our clinical experience, the patient’s style of desire – spontaneous or responsive – can be either a positive or negative factor, depending on the needs of the patient and their partner(s). Careful questioning about how a patient experiences their desire (or lack thereof) can go a long way towards helping the match patients to more appropriate interventions for their sexual wellbeing. For example, for a woman who experiences predominantly responsive sexual desire, increasing attention to sexual cues may have a greater impact than for a woman who experiences spontaneous desire. In some cases, simple education as to the different styles of sexual desire, with reassurance that they are all healthy and normal ways to experience one’s sexuality, can be a powerful intervention in and of itself.

As described above, sexual desire may be unlike other basic drives. In the case of a true drive, the behaviors associated with that drive are reinforced by relief of the urgency associated with that drive: the reward for eating when you are hungry is that you no longer feel hungry. But in the case of sexual desire, the associated behaviors (i.e., initiation or receptivity to initiation of sexual activity) are reinforced by the rewarding qualities of the act itself (26), including orgasm (28) as well as intimacy and pleasure (29, 30). Put simply: if the sex a woman is having is not very fun, it is not surprising that she would not be very motivated to seek it out.

Considering pleasure becomes particularly salient when considering the two culprits of low desire: low excitation and high inhibition. As noted above, several theoretic models of women’s sexual function posit that desire and arousal emerge as a function of competing forces of excitation and inhibition (12, 13). This idea can be described to patients as having either no gas in the tank (low excitation or interest) or a sticky brake pad (high inhibition): either alone can slow you down, and their combination will grind you to a halt. Women experiencing low desire may receive much advice on lowering their inhibitions (e.g., “try a glass of wine to get you in the mood”) but considerably less attention to increasing their pleasure. However, much research has demonstrated that when sex lacks pleasure and reward, female sexual desire quickly withers (31), suggesting that interventions that address only inhibitory factors will likely fail. Thus, the mind-body-spirit approach places pleasure at the center of conversations about desire: what aspects of sex are rewarding for the patient, and how can we build on those?

Central physical factors relating to women’s sexual wellbeing

First and foremost, an integrative clinician must consider the patient’s health habits and self-care practices. Preventative health behaviors such as maintaining a healthy diet, engaging in regular physical activity, keeping a regular sleep schedule, avoiding excessive consumption of alcohol and other drugs, managing stress, quitting smoking, and completing preventative screenings – all of these are foundational to sexual wellbeing, as they are to basic health. It is easy to forget how central these behaviors are when the patient presents with a complicated health history – and yet, much research shows that any other intervention we apply will have at best a limited impact if the patient is not engaging in these basic health practices (32). For women, we would another item on this list – scheduling time for self-care – and reinforcing this as a basic health habit akin to diet and exercise. Girls and women are often socialized to consider the needs of others before their own (33). Learning the habit of scheduling time to engage in the above-mentioned preventative health habits, as well as pleasure-oriented leisure activities, can be framed as building a skill that will translate into learning to advocate for one’s sexual needs and desires.

In addition to these health habits, there are physical factors that span across different medical conditions that appear to have particular relevance for women’s sexual wellbeing. Inflammation, particularly chronic inflammation, can significantly contribute to women’s lower sexual desire and arousal, both directly (by influencing neural activity related to sexual motivation and reward processing) and indirectly (e.g., contributing to disturbances of genital blood flow that restrict sexual arousal (34)). Both hyper- and hypogonadism can contribute to female sexual dysfunction and should be considered as potential contributing factors; however, while treatments that target estrogenic and/or androgenic systems have shown positive effects on sexual functioning these populations (35, 36), caution is warranted for applying these treatments to eugonadal women (37). Anhedonia, or the loss of desire or pleasure, commonly co-occurs across a range of psychiatric disorders such as psychosis, mood and anxiety disorders, and is a strong predictor of distressing low desire in women (38). Similarly, autonomic dysregulation (that is, over-activation of the “fight or flight” aspect of the stress system) occurs in a variety of psychiatric conditions such as anxiety and post-traumatic stress. It is hypothesized that autonomic dysregulation during the menopausal transition may also contribute to hot flashes and night sweats (39). As autonomic activity is important for facilitating female sexual arousal (40), it is likely that autonomic dysregulation may partially explain the higher incidence of sexual dysfunction in these populations. In the context of anxiety disorders, autonomic dysregulation can also contribute significantly to pain, including sexual pain. Epidemiological studies confirm anxiety disorders to be risk factors for low sexual desire and arousal, orgasmic difficulties and sexual pain (41).

To that end, sexual pain is a significant, and often overlooked factor that has significant impacts on all aspects of sexual wellbeing (42). When a woman is in menopause, pain with intercourse can be caused by genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM). GSM causes bothersome symptoms of genitourinary syndrome of menopause include pain with insertion, itching, burning and vaginal dryness (43). Many health care professionals treat GSM with a low dose topical vaginal estrogen such as creams, tablets or rings. However, as noted above, recent research has shown mixed effects of estrogen treatments on sexual wellbeing. For example, one well-controlled randomized clinical trial showed that vaginal estrogens have similar efficacy to either a vaginal moisturizer or placebo in improving painful intercourse (44). In other words, patients may be encouraged to consider an over-the-counter moisturizer or lubricant as first line treatment for genitourinary syndrome of menopause, as this may have similar efficacy to a vaginal estrogen. Another treatment possibility to manage vaginal dryness and pain with intercourse that is gaining popularity is vaginal rejuvenation using energy-based devices like radiofrequency and laser therapy. A few studies of fractional CO2 laser treatments suggest efficacy in managing GSM symptoms up to one year following treatment (45); however, these studies have generally been small and not placebo-controlled, leading the FDA to warn that safety and effectiveness of laser treatments not been established (46).

Finally, many medications have sexual side effects, including hormonal contraceptives, antidepressants and antipsychotics, cancer treatments such as tamoxifen, cholesterol and blood pressure medications, and anti-inflammatory medications (34, 47–51); these side effects should also be considered a target for possible intervention.

Central spiritual factors relating to women’s sexual wellbeing

Spiritual health is a dimension that may be novel for health care providers; however, an integrative and culturally competent approach to medicine encompasses a holistic view of the whole person including spirituality. Spirituality is defined as a search for meaning, purpose, and transcendence and a connection to the significant or sacred (52). This could include connection to oneself, others and/ora higher being. In particular, cultivating connection to one’s own moment-to-moment experience – that is, improving one’s mindfulness – has proven to be a powerful tool for promoting sexual wellness in a variety of populations including survivors of sexual assault and cancer survivors (53). Even brief mindfulness-based interventions can have a significant positive effect on sexual desire, subjective arousal, lubrication, orgasm, sexual satisfaction, and sexual distress among women with sexual problems (54). Mindfulness, or the skill of cultivating a moment to moment awareness by purposefully paying attention to the present experience with a non-judgmental attitude (55), may be incorporated into an explicitly religious or spiritual practice, or may be cultivated on its own. On the other hand, distraction or inattention during sexual activity has been shown to reduce sexual interest and pleasure (56). Similarly, having a sense of purpose can aid not only in coping with stress, it can contribute to sexual satisfaction. One study found that a greater sense of purpose in life was significantly associated with greater enjoyment of sexually intimate activities in midlife women (57). As part of the discussion about a patient’s sexual health, inclusion of sense of purpose in general broadens the conversation.

Patients define spirituality differently. For some, spirituality and religion overlap and for others there is no intersection. Here again we must emphasize the importance of considering religion as both potentially positive and negative: although there may be a perception that religion can only inhibit sexual satisfaction, much research suggests religion can have a range of effects on sexuality. For example, one study of newly married, heterosexual couples found that greater sanctification of marital sexuality early in the marriage predicted more frequent sexual intercourse, sexual satisfaction, and marital satisfaction one year later (58). The best approach, then, encourages patients to consider their own religious ideals, and how these manifest in both positive and negative ways: in how their religion instructs them to act in intimate relationships, what kinds of sexual behaviors and sexual partnerships are in line with their ethical principles, and how they feel about their ownership of their own body and physical pleasure. Through this lens, the health care provider can include encourage patients to have increased body awareness, sense of purpose in their lives and in their relationships, and attunement with their religious or moral principles, each of which can augment sexual satisfaction and pleasure.

Distal aspects of sexual wellbeing

The distal aspects radiate outwards from the central aspects: they are the patient’s surface-level concerns and assets in each dimension. Because distal aspects are more readily apparent to both the patient and the provider, they are experienced as more urgent to address, and thus more likely to be the target of intervention in routine clinical care. Targeting distal aspects is not necessarily bad, but patients (and their providers) should be aware that focusing all efforts solely on managing these issues will provide more limited benefits than targeting the central aspects noted above.

Distal mental, physical, and spiritual factors relating to women’s sexual wellbeing

In terms of mental factors, automatic thoughts – surface-level, instantaneous and habitual images or words that are manifestations of core beliefs – may be either positive or negative in their effect on sexual wellbeing. Automatic thoughts are associated with changes in mood and guide our actions in response to internal or external triggers: for example, the thought “my partner thinks I am sexy” will cause a very different set of feelings and behaviors than “my body is so disgusting”. Patients may be encouraged to pinpoint when their mood suddenly changes in response to sexual cues to figure out what ran through their head immediately beforehand, noting any patterns and challenging distorted or unproductive thoughts. This process, called cognitive restructuring, is foundational to cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). Patients may be encouraged to work with a therapist trained in CBT techniques, or to use one of the many online CBT self-help resources, such as https://moodgym.com.au/, which is a free program that has been extensively studied and shown to improve symptoms of depression, anxiety and general psychological distress (59). Several online CBT interventions specifically oriented to female sexual dysfunctions have been tested with very promising results (60, 61).

In terms of physical factors, there are a great many medical conditions that are known to impact sexual functioning, such as metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease, cancer, GSM, chronic pelvic pain, polycystic ovarian syndrome, and psychiatric conditions such as depression and anxiety (62). We list these factors as “distal” not because they are unimportant, but because addressing their impact on sexuality will have a more limited effect without addressing the central factors described above. Often, the specific symptoms of these conditions act as a trigger or catalyst for sexual dysfunction but are not themselves the root cause; careful questioning can reveal how that symptom causing distress, which can inform treatment. For example, chronic pelvic pain may trigger catastrophizing and worries about partner’s reactions to having to change sexual patterns (30, 63) – the most effective interventions, then, might include discussions with the patient’s partner about sexual communication and flexibility.

Finally, patients may lack awareness of the spiritual dimension of their health. Although many patients welcome the discussion with their health care providers about what spirituality means to them, and how it may guide their care decisions, others may be initially reluctant or need guidance on how to consider spirituality as it connects to their sexual healthcare. Encouraging meaningful rituals that promote sexual pleasure and satisfaction, and that create a sense of connection to one’s sexuality, can be a gentle introduction to spiritual health for such patients. A ritual is a symbolic activity that is performed before, during, or after a meaningful event in order to achieve some desired outcome (64). Rituals can focus our attention as well. Cultures throughout the world build connections through rituals. Enacting a ritual from one’s religion, or creating one for oneself, encourages us to go deeper and tap into our connection to ourselves, our partners, and/or a higher being. An intimacy ritual might involve connecting by engaging one’s senses with music, aromatherapy, massage or grounded attention to the sight of one’s partner. Practitioners who are aware of the ways in which positive spiritual coping strategies serve as facilitators to health care may encourage patients to take a more active role in their overall health and wellness and frame messages to increase patient adherence to health promoting behaviors (65).

The mind-body-spirit model encourages patients to find their best self in terms of sexual wellness, and provides a framework for shared decision making that incorporates holistic dimensions of health. Below, we present a case study in which each dimension is assessed and considered as a target for intervention.

The mind-body-spirit model in action: A case study

AW is a 56 year old female who has a history of metabolic syndrome and anxiety. She presented to her primary care physician for a routine checkup. At her last physician visit 6 months ago, she was told that she has pre-diabetes. She has been worried about whether her fasting glucose has increased into the range of diabetes since she was not able to institute all of the recommended healthy lifestyle changes; however, at present her pre-diabetes is being treated with lifestyle changes as she does not take any medication.

Her exercise history is variable, consisting mainly of cycling classes or walking. Some weeks she exercises 2 days a week, some weeks not at all. She eats a plant-based diet with minimal red meat, but she snacks often on sugary foods. She is a former smoker and drinks socially on the weekends. Reinforcing her positive efforts towards healthy diet and exercise, praising her for quitting smoking, identifying her triggers for emotional eating of sugary foods, and helping her troubleshoot barriers to exercising were all interventions for addressing these central physical aspects of sexual wellness.

AW stated her mother had breast cancer at age 49, and her father has type 2 diabetes diagnosed in his 50’s. She has been married to her husband for 25 years and they have a son in college. She went into menopause at age 45 and she has minimal hot flashes.

Previously, she had taken a benzodiazepine as needed for situational anxiety. Now, she practices deep breathing when she starts to feel anxious, and has not used medication for anxiety for over 10 years. However, she says that she has a hard time falling asleep as her mind is often racing, noting that work is more stressful lately as her department is short staffed and she has been working longer hours. Her anxiety was assessed in detail, as it likely to be a central mental aspect of her sexual wellness, and thus a key target for intervention.

When asked about her sex life, she says that the issue that concerns her the most is that she has very low desire: sex is so painful that it “feels like pieces of glass” in her vagina during intercourse, leading to low interest in sex. She is able to achieve an orgasm with partnered sex but it takes longer than she would like. She also says that she worries about her teenage son when he is out with his friends, leading to ruminating thoughts about his safety instead of focusing on intimacy. In addition, she states that she has been uncomfortable with the changes in her body as she has gained weight since entering menopause. Her husband tells her that she is attractive but she doesn’t feel as attractive as she once was. She says that she wishes there was a pill to help with her sex life. When asked about what gives her life a sense of purpose and a connection, she says that sexuality is a part of her life that is missing.

One of the key steps in helping AW was to address her pain with intercourse. As had been initially suspected, anxiety was a central factor. AW was given some brief education on how anxiety can impact a women’s ability to focus in on pleasure and body awareness. A discussion on mediation was also helpful, with specific focus on how mindfulness can help her with anxiety as well as with sexuality. This discussion included the connection between anxiety and pain with intercourse. During the discussion on mindfulness, AW was also encouraged to use mindfulness to explore sexually satisfying behaviors and add creativity to her sexual experience. AW was reinforced for her efforts at positive coping with anxiety in her use of deep breathing exercises, offered tools for managing her anxious automatic thoughts, and recommended to a therapist to further expand her coping toolbox. The conversation included adding sexual variety with sex aids like vibrators, which have been shown to significantly improve women’s sexual function (66).

Additionally, AW was oriented to the different types of lubricants and moisturizers including water based, silicone based and oil based, in addition to the benefits of a glycerin-free option. She was invited to explore these options with samples in the office that she could feel on her fingers to help her make her decision. She shared that she was concerned about using vaginal estrogen due to her mother’s history of breast cancer. Accordingly, AW was given information about the minimal systemic estrogen absorption during low dose vaginal estrogen therapy, and told that during vaginal therapies, estradiol levels remain in the postmenopausal range (67). Despite hearing that information, she still did not feel comfortable with vaginal estrogen, so we discussed additional non-hormonal options if she found that OTC lubricants and moisturizers were not sufficient to relieve her pain with intercourse, like hyaluronic vaginal gel. Hyaluronic acid vaginal gel, used every 3 days, has been associated with improvement in symptoms of vaginal dryness comparable to that seen with estriol cream without a change in pH (67). AW was glad that she had good non-hormonal options. We also discussed energy-based vaginal rejuvenation therapies, weighing the benefits vs the harm of these treatments. Following the guidance of the North American Menopause Society (68), AW was informed that energy-based treatments use FDA-approved devices, but have not yet received FDA approval for management of GSM, sexual function, incontinence, or pelvic laxity. We discussed how short-term data are promising, but that more robust, sham-controlled, and longer-term data are needed. In addition, given her history of significant pain with intercourse, AW was also referred to a pelvic floor physical therapist.

Finally, we discussed the intersection of spirituality and sexual well-being. For AW, a core value was feeling connected to her partner. We discussed incorporating rituals into their intimacy to augment a sense of meaning and give her motivation. AW was invited to start a yoga practice to help with the mind – body connection. She was open to this as she had already has seen the benefits of deep breathing for her anxiety. Studies have shown that a yoga practice reduces negative affect, increases positive affect, increase subjective feeling of energy and increases positive self-esteem (69). For AW, yoga could also be a way to strive for self-confidence and body acceptance, as low body esteem was a key driver of her negative sexual self-schema (which in turn was a central mental aspect of her presentation). Then we discussed the connection between yoga and sexuality. A small study of women found that yoga can produce improvement sexual desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain (70).

At each step of the visit, the objective was to listen to the patient and offer management options that align with her viewpoint and individual needs in each dimension, and encourage her to share fully in the decision making. In the end, AW left the appointment with a treatment plan that addressed the mental, physical, and spiritual dimensions of her sexuality, and created a road map for her journey to wellness.

Summary

In this article, we have presented a model for clinical assessment and management of women’s sexual wellbeing. Interdisciplinary, biopsychosocial approaches to clinical management of sexual functioning improve patient outcomes relative to treatment-as-usual (4, 71, 72), particularly for cases that include sexual pain (73). In addition to improved symptom reduction, patient-oriented approaches such as the one presented here may also reduce attrition and improve patient engagement with care (73), especially among women like AW whose concerns about medication side effects benefit from discussion about where medication fits into a multimodal approach to sexual wellbeing (74). However, to date the mind-body-spirit model has not been empirically tested against traditional therapies (psychological or pharmaceutical). Not only do we need randomized comparison trials to establish incremental efficacy above and beyond other treatment approaches, but also cost effectiveness trials assessing the benefits of such a resource-intensive approach. One promising possibility is the application of the mind-body-spirit approach to the growing telehealth offerings for sexual and reproductive health (75–77), serving as a shared framework linking treatments across modalities. Given the high clinical demand for integrative and holistic approaches to sexual wellbeing (77), such trials are clearly needed.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Politi MC, Clark MA, Armstrong G, McGarry KA, Sciamanna CN. Patient-provider communication about sexual health among unmarried middle-aged and older women. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(4):511–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gott M, Galena E, Hinchliff S, Elford H. “Opening a can of worms”: GP and practice nurse barriers to talking about sexual health in primary care. Fam Pract. 2004;21(5):528–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parish SJ, Hahn SR, Goldstein SW, Giraldi A, Kingsberg SA, Larkin L, et al. The International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health Process of Care for the Identification of Sexual Concerns and Problems in Women. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(5):842–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clayton AH, Goldstein I, Kim NN, Althof SE, Faubion SS, Faught BM, et al. The International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health process of care for management of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in women. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;93(4):467–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simon J, Davis S, Althof S, Chedraui P, Clayton A, Kingsberg S, et al. Sexual well-being after menopause: an international menopause society white paper. Climacteric. 2018;21(5):415–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rostosky SS, Wilcox BL, Wright MLC, Randall BA. The impact of religiosity on adolescent sexual behavior: A review of the evidence. J Adolesc Res. 2004;19(6):677–97. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davidson JK, Darling CA, Norton L. Religiosity and the sexuality of women: Sexual behavior and sexual satisfaction revisited. J Sex Res. 1995;32(3):235–43. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahrold TK, Farmer M, Trapnell PD, Meston CM. The relationship among sexual attitudes, sexual fantasy, and religiosity. Arch Sex Behav. 2011;40(3):619–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahrold TK, Meston CM. Ethnic differences in sexual attitudes of US college students: Gender, acculturation, and religiosity factors. Arch Sex Behav. 2010;39(1):190–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rullo J, Faubion SS, Hartzell R, Goldstein S, Cohen D, Frohmader K, et al. Biopsychosocial management of female sexual dysfunction: a pilot study of patient perceptions from 2 multi-disciplinary clinics. Sexual medicine. 2018;6(3):217–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.*.Bell IR, Caspi O, Schwartz GE, Grant KL, Gaudet TW, Rychener D, et al. Integrative medicine and systemic outcomes research: issues in the emergence of a new model for primary health care. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(2):133–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This article introduces the integrative medicine framework, which is the foundation of the mind-body-spirit model presented here.

- 12.Bancroft J, Graham CA, Janssen E, Sanders SA. The dual control model: Current status and future directions. J Sex Res. 2009;46(2-3):121–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perelman MA. The Sexual Tipping Point®: A mind/body model for sexual medicine. The journal of sexual medicine. 2009;6(3):629–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gundy JM, Woidneck MR, Pratt KM, Christian AW, Twohig MP. Acceptance and commitment therapy: State of evidence in the field of health psychology. Scientific Review of Mental Health Practice. 2011;8(2):23–35. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruiz FJ. A review of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) empirical evidence: Correlational, experimental psychopathology, component and outcome studies. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy. 2010;10(1):125–62. [Google Scholar]

- 16.**.Andersen BL, Cyranowski JM. Women’s sexual self-schema. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994;67(6):1079–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This article first introduced the concept of sexual self-schema, and their role in women’s sexual wellbeing.

- 17.Cyranowski JM, Aarestad SL, Andersen BL. The role of sexual self-schema in a diathesis–stress model of sexual dysfunction. Journal of Applied Preventive Psychology. 1999;8(3):217–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niehaus AF, Jackson J, Davies S. Sexual self-schemas of female child sexual abuse survivors: Relationships with risky sexual behavior and sexual assault in adolescence. Arch Sex Behav. 2010;39(6): 1359–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pulverman CS, Boyd RL, Stanton AM, Meston CM. Changes in the sexual self-schema of women with a history of childhood sexual abuse following expressive writing treatment. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2017;9(2):181–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meston CM, Lorenz TA, Stephenson KR. Effects of Expressive Writing on Sexual Dysfunction, Depression, and PTSD in Women with a History of Childhood Sexual Abuse: Results from a Randomized Clinical Trial. 2013;10(9):2177–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dozois DJ, Bieling PJ, Patelis-Siotis I, Hoar L, Chudzik S, McCabe K, et al. Changes in self-schema structure in cognitive therapy for major depressive disorder: A randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(6):1078–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meana M Elucidating women’s (hetero) sexual desire: Definitional challenges and content expansion. J Sex Res. 2010;47(2-3): 104–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.**.Basson R Women’s sexual desire: Disordered or misunderstood? J Sex Marital Ther. 2002;28:17–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This article describes spontaneous vs. responsive models of sexual desire, and how allowing for different kinds of sexual desire in clinical evaluations may help women feel less pathologized.

- 24.Timmers AD, Dawson SJ, Chivers ML. The effects of gender and relationship context cues on responsive sexual desire in exclusively and predominantly androphilic women and gynephilic men. The Journal of Sex Research. 2018;55(9):1167–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamilton LD, Meston CM. The effects of partner togetherness on salivary testosterone in women in long distance relationships. Hormones and Behavior. 2010;57(2):198–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pfaus JG, Scepkowski LA. The biologic basis for libido. Current Sexual Health Reports. 2005;2(2):95–100. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sand M, Fisher WA. Women’s Endorsement of Models of Female Sexual Response: The Nurses’ Sexuality Study. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2007;4(3):708–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coria-Avila GA, Herrera-Covarrubias D, Ismail N, Pfaus JG. The role of orgasm in the development and shaping of partner preferences. Socioaffective neuroscience & psychology. 2016;6(1):31815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stephenson KR, Meston CM. Why is impaired sexual function distressing to women? The primacy of pleasure in female sexual dysfunction. The journal of sexual medicine. 2015;12(3):728–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stephenson KR, Meston CM. When are sexual difficulties distressing for women? The selective protective value of intimate relationships. The journal of sexual medicine. 2010;7(11):3683–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pfaus JG, Kippin TE, Coria-Avila GA, Gelez H, Afonso VM, Ismail N, et al. Who, What, Where, When (and Maybe Even Why)? How the Experience of Sexual Reward Connects Sexual Desire, Preference, and Performance. Arch Sex Behav. 2012;41(1):31–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hunter CL, Goodie JL, Oordt MS, Dobmeyer AC. Integrated behavioral health in primary care: Step-by-step guidance for assessment and intervention: American Psychological Association; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hastings PD, McShane KE, Parker R, Ladha F. Ready to make nice: Parental socialization of young sons’ and daughters’ prosocial behaviors with peers. The Journal of Genetic Psychology. 2007; 168(2): 177–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lorenz TK. Interactions Between Inflammation and Female Sexual Desire and Arousal Function. Current Sexual Health Reports. 2019; 11(4):287–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Santoro N, Worsley R, Miller KK, Parish SJ, Davis SR. Role of estrogens and estrogen-like compounds in female sexual function and dysfunction. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2016;13(3):305–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Achilli C, Pundir J, Ramanathan P, Sabatini L, Hamoda H, Panay N. Efficacy and safety of transdermal testosterone in postmenopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2017;107(2):475–82. e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cappelletti M, Wallen K. Increasing women’s sexual desire: The comparative effectiveness of estrogens and androgens. Hormones and Behavior. 2016;78:178–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shankman SA, Katz AC, DeLizza AA, Sarapas C, Gorka SM, Campbell ML. The different facets of anhedonia and their associations with different psychopathologies. Anhedonia: A Comprehensive Handbook Volume 1: Springer; 2014. p. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Freedman RR. Hot flashes: behavioral treatments, mechanisms, and relation to sleep. The American journal of medicine. 2005;118(12):124–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lorenz T, Harte CB, Hamilton LD, Meston CM. Evidence for a curvilinear relationship between sympathetic nervous system activation and women’s physiological sexual arousal. Psychophysiology. 2012;49(1): 111–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Basson R, Gilks T. Women’s sexual dysfunction associated with psychiatric disorders and their treatment. Womens Health. 2018;14:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Al-Abbadey M, Liossi C, Curran N, Schoth DE, Graham CA. Treatment of Female Sexual Pain Disorders: A Systematic Review. J Sex Marital Ther. 2016;42(2):99–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simon JA, Goldstein I, Kim NN, Davis SR, Kellogg-Spadt S, Lowenstein L, et al. The role of androgens in the treatment of genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM): International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH) expert consensus panel review. Menopause. 2018;25(7):837–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.*.Mitchell CM, Reed SD, Diem S, Larson JC, Newton KM, Ensrud KE, et al. Efficacy of Vaginal Estradiol or Vaginal Moisturizer vs Placebo for Treating Postmenopausal Vulvovaginal Symptoms: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(5):681–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This article describes over-the-counter lubricants as an alternative to vaginal estrogen treatments for vuvlovaginal symptoms.

- 45.Sokol ER, Karram MM. Use of a novel fractional CO2 laser for the treatment of genitourinary syndrome of menopause: 1-year outcomes. Menopause. 2017;24(7):810–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Food and Drug Administration (FDA). FDA Warns Against Use of Energy-Based Devices to Perform Vaginal ‘Rejuvenation’ or Vaginal Cosmetic Procedures: FDA Safety Communication. In: Education DoIaC, editor. Washington, DC: U.S. Food and Drug Administration; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lorenz T, Rullo J, Faubion S. Antidepressant-Induced Female Sexual Dysfunction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(9):1280–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lorenz TK. Antidepressant Use During Development May Impair Women’s Sexual Desire in Adulthood. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2020;17(3):470–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Burrows LJ, Basha M, Goldstein AT. The Effects of Hormonal Contraceptives on Female Sexuality: A Review. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2012;9(9):2213–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mourits M, Böckermann I, De Vries E, Van der Zee A, Ten Hoor K, Van der Graaf W, et al. Tamoxifen effects on subjective and psychosexual well-being, in a randomised breast cancer study comparing high-dose and standard-dose chemotherapy. Br J Cancer. 2002;86(10):1546–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thomas HN, Evans GW, Berlowtiz DR, Chertow GM, Conroy MB, Foy CG, et al. Antihypertensive medications and sexual function in women: Baseline data from the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT). J Hypertens. 2016;34(6):1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.*.Sajja A, Puchalski C. Training Physicians as Healers. AMA J Ethics. 2018;20(7):E655–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This articles shares the importance of spirituality in the practice of medicine and how this concept can be incorporated into medical education.

- 53.Stephenson KR, Kerth J. Effects of mindfulness-based therapies for female sexual dysfunction: A meta-analytic review. The Journal of Sex Research. 2017;54(7):832–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dosch A, Rochat L, Ghisletta P, Favez N, Van der Linden M. Psychological Factors Involved in Sexual Desire, Sexual Activity, and Sexual Satisfaction: A Multi-factorial Perspective. Arch Sex Behav. 2016;45(8):2029–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Khoury B, Sharma M, Rush SE, Fournier C. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for healthy individuals: A meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2015;78(6):519–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pascoal PM, Rosa PJ, Silva EPd, Nobre PJ. Sexual beliefs and sexual functioning: The mediating role of cognitive distraction. International Journal of Sexual Health. 2018;30(1):60–71. [Google Scholar]

- 57.**.Prairie BA, Scheier MF, Matthews KA, Chang CC, Hess R. A higher sense of purpose in life is associated with sexual enjoyment in midlife women. Menopause. 2011;18(8):839–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study showed a significant positive role for religiosity and sense of purpose in women’s sexual wellbeing at midlife.

- 58.Hernandez K, Mahoney A. Sex Through a Sacred Lens: Longitudinal Effects of Sanctification of Marital Sexuality. J Fam Psychol. 2018;32(4):425–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Twomey C, O’Reilly G. Effectiveness of a freely available computerised cognitive behavioural therapy programme (MoodGYM) for depression: Meta-analysis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2017;51(3):260–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hucker A, McCabe MP. Incorporating Mindfulness and Chat Groups Into an Online Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Mixed Female Sexual Problems. J Sex Res. 2015;52(6):627–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hummel SB, van Lankveld JJ, Oldenburg HS, Hahn DE, Broomans E, Aaronson NK. Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for sexual dysfunctions in women treated for breast cancer: design of a multicenter, randomized controlled trial. BMC Cancer. 2015;15(1):321- [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McCabe MP, Sharlip ID, Lewis R, Atalla E, Balon R, Fisher AD, et al. Risk factors for sexual dysfunction among women and men: a consensus statement from the Fourth International Consultation on Sexual Medicine 2015. The journal of sexual medicine. 2016; 13(2): 153–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pereira R, Oliveira C, Nobre P. Impact of Partner’s Sexual and Relationship Well-Being on Pain Intensity and Pain Catastrophizing in Women With Genital Pain. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2017;14(5):e309. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Norton MI, Gino F. Rituals alleviate grieving for loved ones, lovers, and lotteries. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2014;143(1):266–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Isaac KS, Hay JL, Lubetkin EI. Incorporating Spirituality in Primary Care. J Relig Health. 2016;55(3): 1065–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rullo JE, Lorenz T, Ziegelmann MJ, Meihofer L, Herbenick D, Faubion SS. Genital vibration for sexual function and enhancement: best practice recommendations for choosing and safely using a vibrator. Sex Relation Ther. 2018;33(3):275–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Faubion SS, Sood R, Kapoor E. Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause: Management Strategies for the Clinician. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(12):1842–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.**.FDA Mandating Vaginal Laser Manufacturers Present Valid Data Before Marketing [press release]. The North American Menopause Society; 2018. [Google Scholar]; This document warns patients and practioners against paying attention to advertising campaigns for vaginal treatments when clinical trial data are not yet fully supportive of these treatments.

- 69.Golec de Zavala A, Lantos D, Bowden D. Yoga Poses Increase Subjective Energy and State Self-Esteem in Comparison to ‘Power Poses’. Front Psychol. 2017;8:752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dhikav V, Karmarkar G, Gupta R, Verma M, Gupta R, Gupta S, et al. Yoga in female sexual functions. J Sex Med. 2010;7(2 Pt 2):964–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Thomas HN, Thurston RC. A biopsychosocial approach to women’s sexual function and dysfunction at midlife: A narrative review. Maturitas. 2016;87:49–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Carcieri EM, Mona LR. Assessment and Treatment of Sexual Health Issues in Rehabilitation: A Patient-Centered Approach. In: Budd MA, Hough S, Wegener ST, Stiers W, editors. Practical Psychology in Medical Rehabilitation. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2017. p. 287–94. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bergeron S, Corsini-Munt S, Aerts L, Rancourt K, Rosen NO. Female Sexual Pain Disorders: a Review of the Literature on Etiology and Treatment. Current Sexual Health Reports. 2015;7(3): 159–69. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thomas HN, Hamm M, Hess R, Borrero S, Thurston RC. Patient-centered outcomes and treatment preferences regarding sexual problems: a qualitative study among midlife women. The journal of sexual medicine. 2017; 14(8): 1011–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Novara G, Checcucci E, Crestani A, Abrate A, Esperto F, Pavan N, et al. Telehealth in Urology: A Systematic Review of the Literature. How Much Can Telemedicine Be Useful During and After the COVID-19 Pandemic? Eur Urol. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zippan N, Stephenson KR, Brotto LA. Feasibility of a Brief Online Psychoeducational Intervention for Women With Sexual Interest/Arousal Disorder. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schover LR, Strollo S, Stein K, Fallon E, Smith T. Effectiveness trial of an online self-help intervention for sexual problems after cancer. J Sex Marital Ther. 2020:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]