Abstract

Introduction:

Stigma has been identified as a key determinant of health and health inequities because of its effects on access to health-enabling resources and stress exposure. Though existing reports offer in-depth summaries of the mechanisms through which stigma influences health, a review of evidence on the upstream drivers of stigma across health and social conditions has been missing. The objective of this review is to summarize known structural determinants of stigma experienced across health and social conditions in developed country settings.

Methods:

We conducted a rapid review of the literature. English- and French-language peer-reviewed and grey literature works published after 2008 were identified using MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, Google and Google Scholar. Titles and abstracts were independently screened by two reviewers. Information from relevant publications was extracted, and a thematic analysis of identified determinants was conducted to identify broad domains of structural determinants. A narrative synthesis of study characteristics and identified determinants was conducted.

Results:

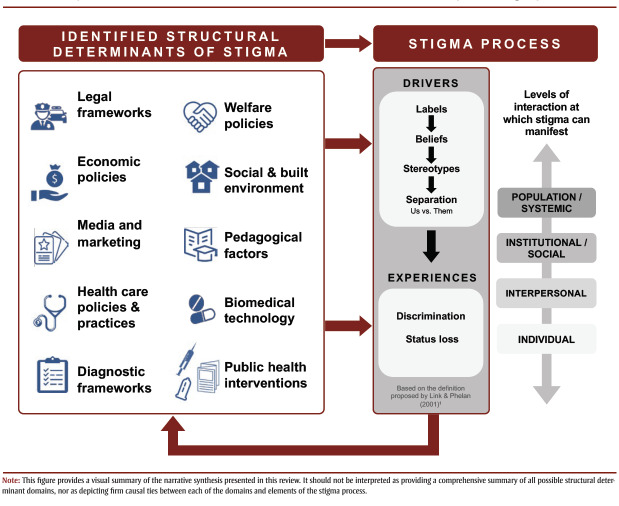

Of 657 publications identified, 53 were included. Ten domains of structural determinants of stigma were identified: legal frameworks, welfare policies, economic policies, social and built environments, media and marketing, pedagogical factors, health care policies and practices, biomedical technology, diagnostic frameworks and public health interventions. Each domain is defined and summarized, and a conceptual framework for how the identified domains relate to the stigma process is proposed.

Conclusion:

At least 10 domains of structural factors influence the occurrence of stigma across health and social conditions. These domains can be used to structure policy discussions centred on ways to reduce stigma at the population level.

Keywords: stigma, discrimination, structural determinants, social conditions, health conditions

Highlights

A review of known structural determinants of stigma operating across health and social conditions has been missing from existing literature.

This study reviewed and synthesized existing literature and identified 10 domains of structural determinants of stigma.

The 10 domains identified were: legal frameworks, welfare policies, economic policies, social and built environments, media and marketing, pedagogical factors, health care policies and practices, biomedical technology, diagnostic frameworks and public health interventions.

The proposed conceptual framework of the 10 domains of structural determinants of stigma can be used to structure future policy discussions on ways to address stigma at the population level.

Introduction

Stigma has been defined as a process enabled by social, economic and political power inequities, through which negative labels, beliefs and perceived differences between groups can culminate in discrimination and status loss.1 As Link and Phelan wrote, “…stigma exists when elements of labelling, stereotyping, separation, status loss and discrimination occur together in a power situation that allows them.”1,p.377 A key social determinant of health, stigma is a cause for concern in many substantive areas of public health practice.2 Stigma-related discrimination and status loss influence health by restricting affected populations’ access to health-enabling resources such as housing, employment, social ties and health care, and by increasing exposure to stress.2

In Canada, the Public Health Agency of Canada’s Chief Public Health Officer (CPHO)’s 2019 report Addressing Stigma: Towards a More Inclusive Health System3 has proposed a conceptual summary of the myriad pathways through which stigma can affect health and health inequities. This and previous frameworks4,5 are helpful for understanding the theoretical underpinnings of the effects of stigma on health and for identifying potential areas for health and social policy intervention.

However, with their in-depth focus on the downstream effects of stigma on health, existing reports typically lack a thorough exploration of the upstream factors that drive stigma,6 particularly those operating at a structural level. Existing literature on structural determinants of stigma tends to focus on stigma pertaining to specific stigmatized experiences, identities, behaviours or health conditions.7,8 A general summary of determinants of stigma across affected populations is currently missing from the literature. This review seeks to fill these gaps in the extant literature by contributing a summary of known structural determinants of stigma across stigmatized populations.

Described as “contextual factors” in the World Health Organization’s Social Determinants of Health Model,9 and structural “practices” in the CPHO’s 2019 report’s Stigma Pathways Model,3 structural determinants can be defined as factors that operate outside the locus of control of individuals,10 such as elements of physical, social, policy or legal environments.11 For example, structural determinants can include various forms of legislation (or lack thereof) to protect individuals’ rights,12 or wealth redistribution policies.9,13 Structural factors are distinct from but tightly influence more proximal, individual-level determinants of health, such as individuals’ access to income, housing, food or safe working conditions.9

The scope of this review is restricted to examining the structural determinants of stigma for several reasons. First, according to public health research and theory, structural factors are considered to be those that create and perpetuate social and economic stratification within societies.9 They are often identified as “root causes” of negative health and social outcomes and health inequities, and therefore merit particular attention from the perspective of population health and health equity promotion.9

Second, in the context of public health practice, structural factors tend to exert influence across multiple social contexts and populations.14 Structural factors are therefore particularly relevant to consider when aiming to understand the determinants of stigma occurring across a multitude of health and social conditions— particularly when many forms of stigma intersect.3

Third, though it is difficult to achieve and often requires intersectoral collaboration,9 structural determinants can theoretically be modified through changes in health and social policy.15 When successful, structural-level interventions are often more impactful and far-reaching than more proximal (i.e. individual-level) interventions at reducing population-level health inequities.9

This review therefore was intended to provide a knowledge summary that, in the Canadian context, can complement the knowledge synthesis of the Canadian CPHO’s report on stigma’s effects on health3 and, more broadly, can be used to structure policy discussions on ways to orient public health interventions to reduce stigma in Canada and abroad. The specific objective of this rapid review was to identify and summarize known structural determinants of stigma in Canada and in similar settings, such as those in other member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Methods

We used a rapid review design.16 Used most frequently within governmental policy contexts when time-related resources are limited,17 a rapid review consists of an evidence review strategy that follows the structure of a systematic review process with abridged components to allow research questions to be addressed in a shorter time frame than is typically needed for a systematic review.16 A defining feature of the rapid review design is its restricted evidence search component,17 which involves a non-exhaustive search of available evidence pertaining to the research question. First, a search strategy to identify presynthesized evidence summaries (reviews, summary reports, conceptual frameworks) is applied. If identified synthesis documents are insufficient, because identified publications are not sufficiently recent or methodologically rigorous, a search for less synthesized evidence, including individual studies, is then conducted based on study relevance. Individual studies are collected until additional works fail to offer new information needed to address the research question or until other time or resource constraints prohibit future searches.16

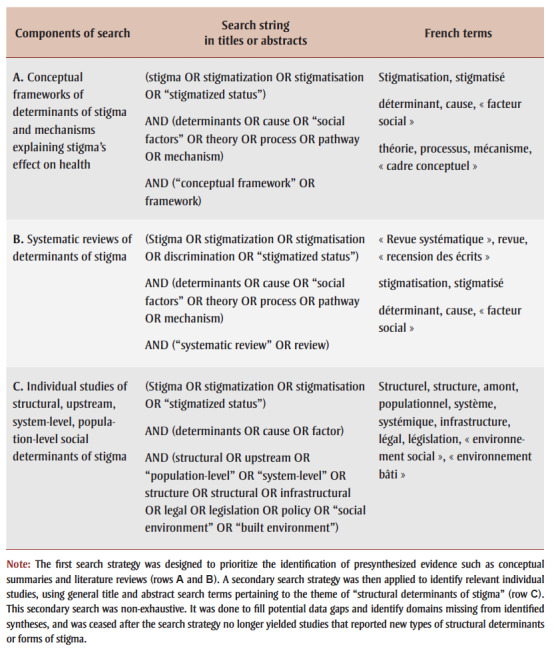

For this review, a first search strategy was designed to prioritize the identification of presynthesized evidence such as conceptual summaries and literature reviews (Table 1, rows A and B).18 A secondary search strategy was then applied to identify relevant individual studies, using general title and abstract search terms pertaining to the theme of “structural determinants of stigma” (Table 1, row C).18 This secondary search was non-exhaustive. It was done to fill potential data gaps and identify domains missing from identified syntheses, and was ceased after the search strategy no longer yielded studies that reported new types of structural determinants or forms of stigma.

Table 1. Summary of components and search strings used to identify relevant references in the literature search on structural determinants of stigma.

|

Eligibility criteria

Works included were those documenting conceptual frameworks, reviews and individual quantitative, qualitative or mixed-methods studies of structural determinants of stigma. We restricted our review to works in English or French (due to the authors’ languages of expertise), published since January 2008, in peer-reviewed or grey-literature sources and set in Canada or other OECD nations. We excluded works without a research design (e.g. commentaries, letters to editors, fact sheets), as well as those that were not available through the Health Canada Health Library network.

Search strategy

MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, Google and Google Scholar databases were searched to ensure appropriate coverage of international health research and social science literature.19Table 1 presents a summary of the search string components. Search strings were also applied in French in Google and Google Scholar, of which the first three pages of results were reviewed. A snowball search approach20 was also used to identify reviews or conceptual summaries that were mentioned in reviewed studies but were not captured through our search strategy.

Study identification, data extraction and quality appraisal

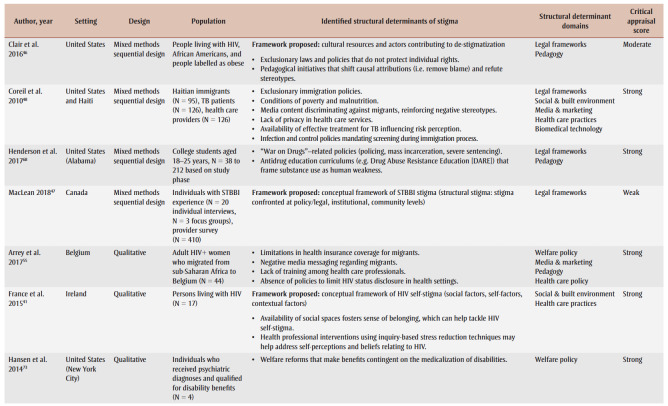

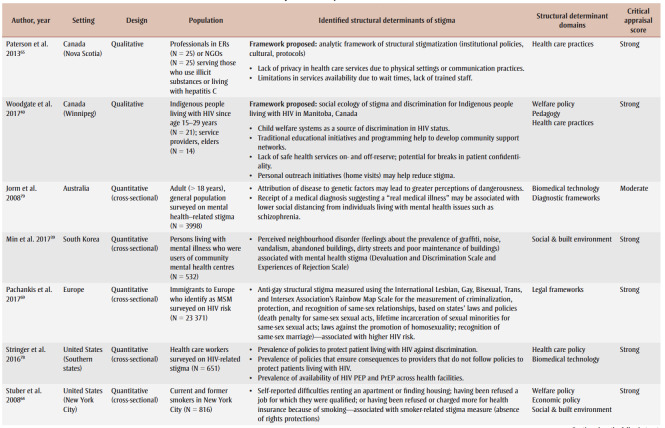

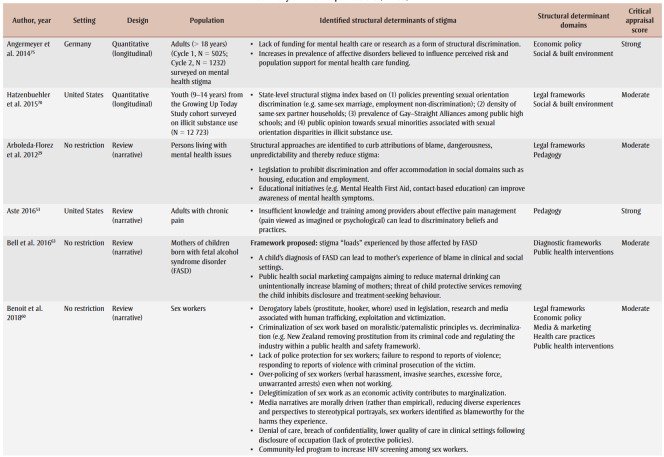

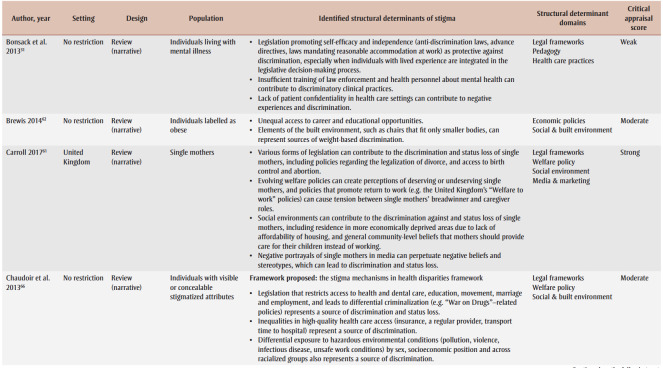

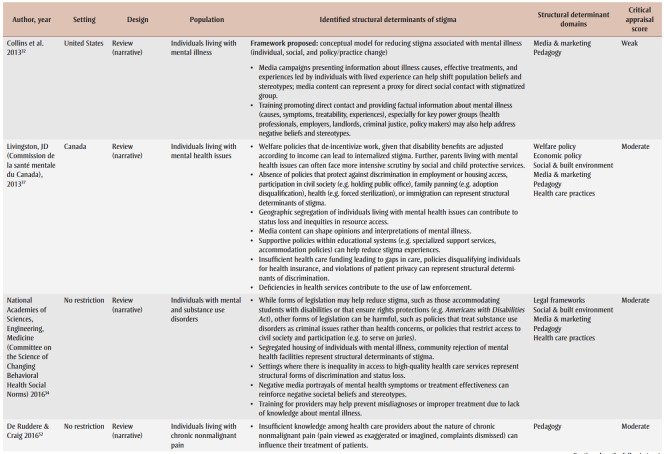

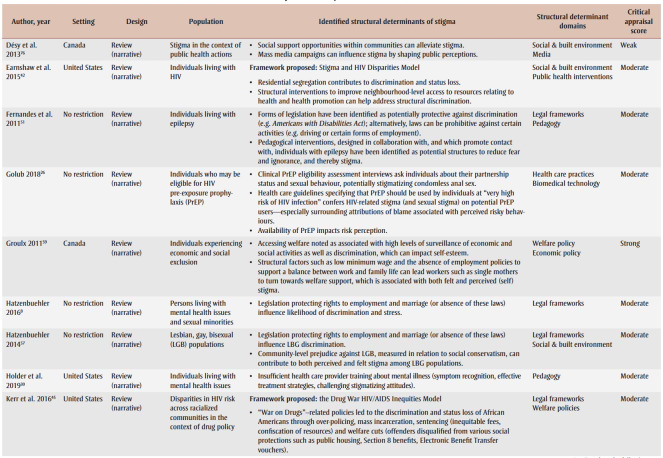

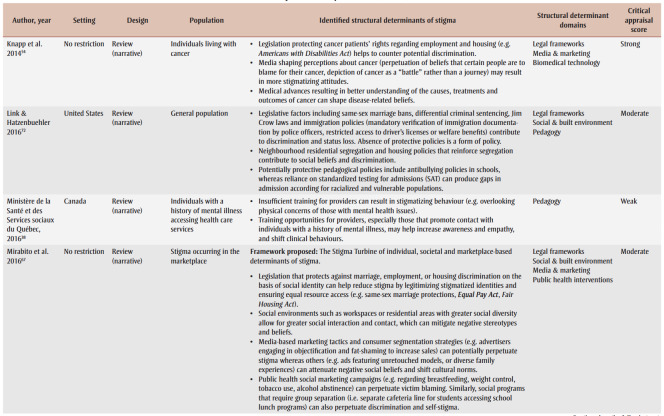

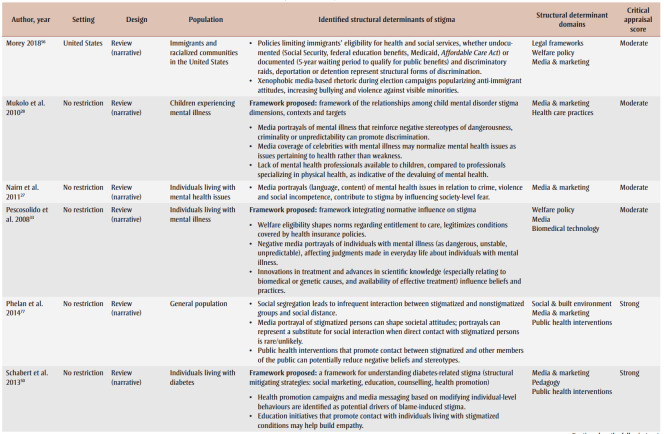

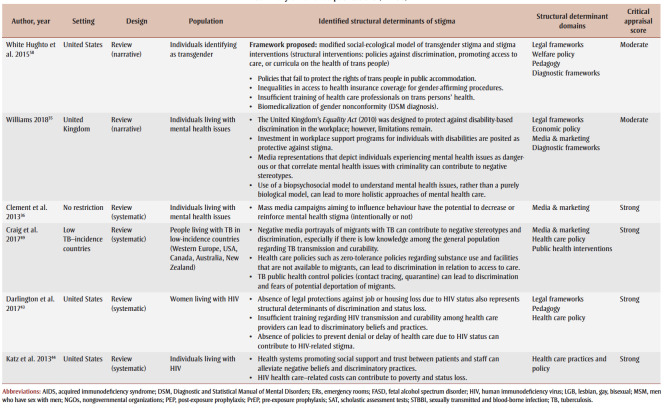

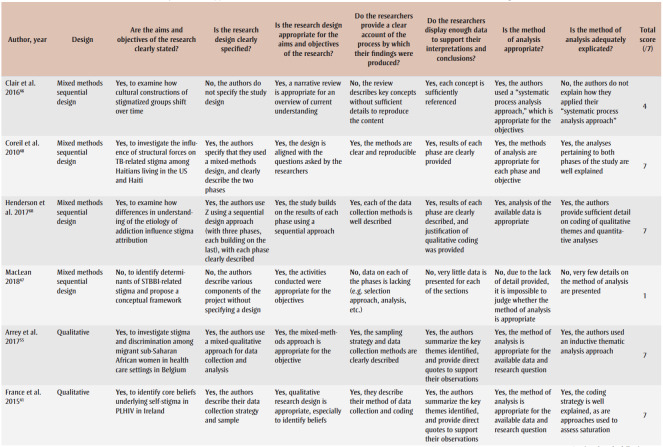

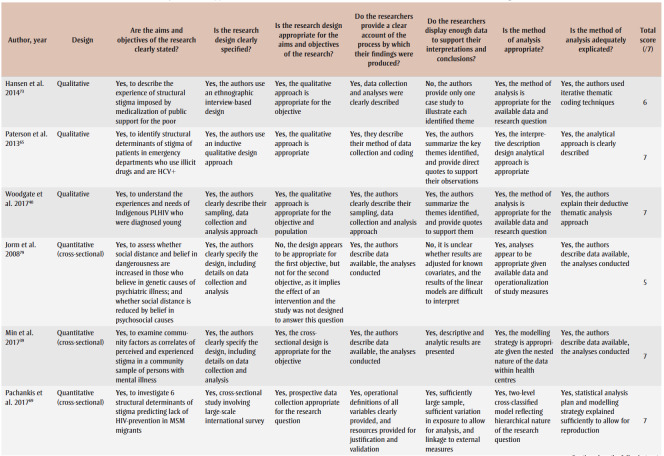

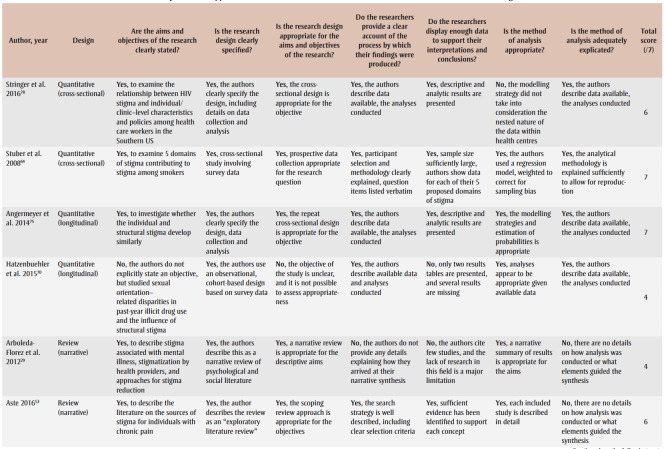

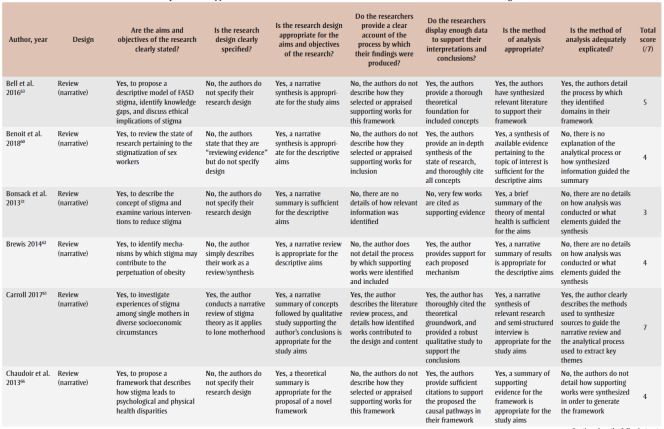

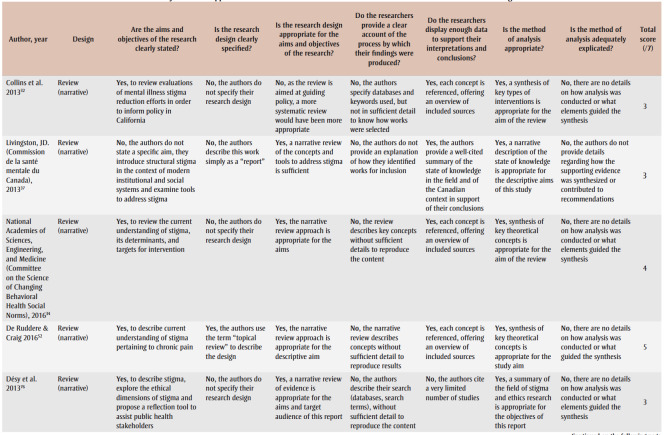

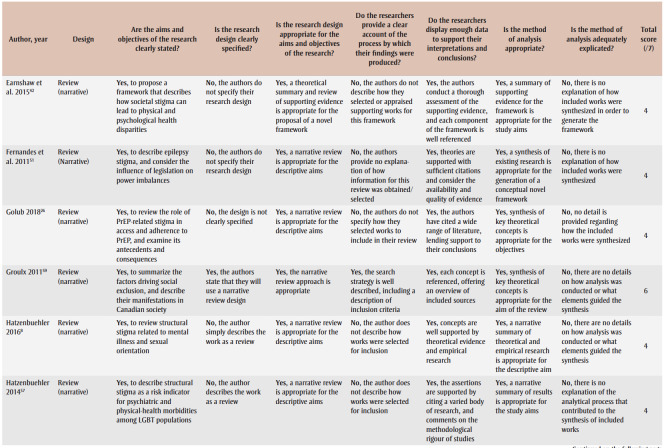

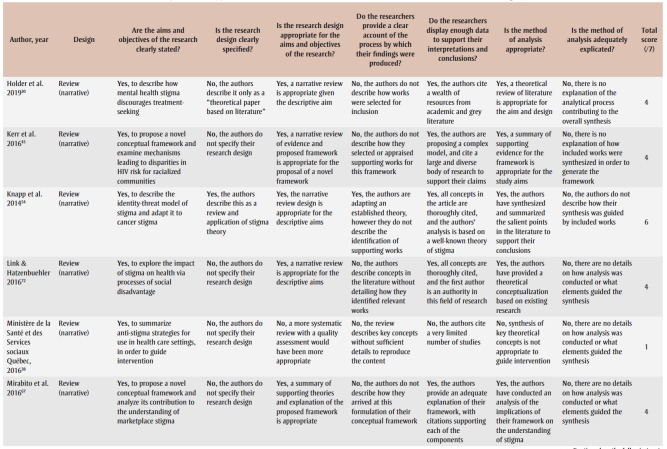

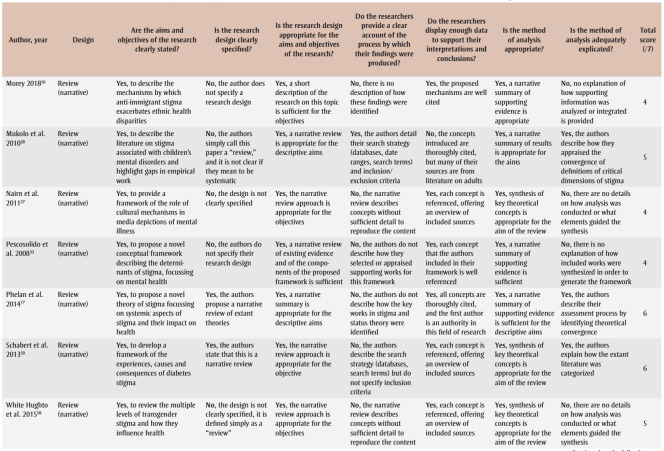

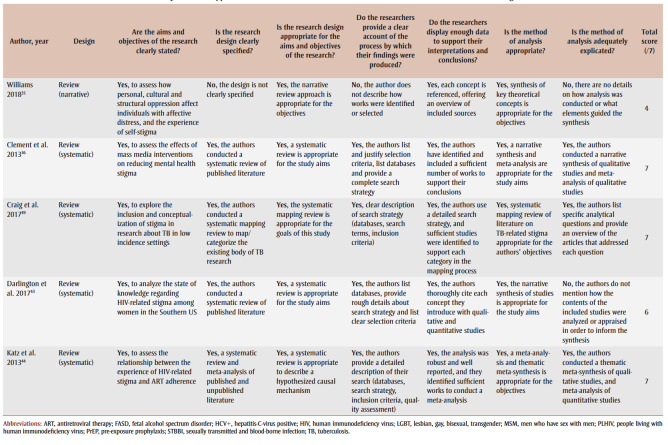

Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts of all identified works, and, based on eligibility criteria, selected works for full-text review through consensus. Four reviewers conducted full-text screening and extracted data on publications’ authors, year of publication, title, country setting, study population and identified structural-level determinants of stigma (Table 2). All data elements were recorded in the data extraction table to enable synthesis of study features and thematic analysis of structural determinants. Two reviewers evaluated the quality of included works using an adaptation of Dixon-Woods et al.’s framework for critical appraisal of works with varied design.21 Seven questions requiring yes-or-no answers were applied to evaluate the quality of each publication (Table 3).

Table 2. Summary of reviewed publications (N = 53).

Table 3. Summary of critical appraisal of identified works in the literature search on structural determinants of stigma.

Data analysis and synthesis

We performed a narrative synthesis of extracted data involving three analytic stages.22 In the first stage, two authors conducted a thematic analysis of documented structural determinants of stigma.23,24 Having become familiar with the data by generating initial summaries of structural determinants reported in included works during the data extraction process, these authors performed a thematic analysis, which involved identifying themes that linked structural determinants conceptually.23,24 Themes were identified semantically (i.e. by interpreting factors that were explicitly mentioned in the texts rather than identifying underlying meanings) and inductively (i.e. without a predefined coding frame), through consensus.25 We considered themes for which related structural factors were mentioned in at least two works, and that were internally coherent and conceptually distinct and definable.24 Hereafter, these themes are described as “domains” of structural determinants.

At the second stage, we proposed a narrative synthesis of study types and characteristics and the identified domains and their relationship to the stigma process, as well as a visual conceptual framework of the domains and their relationship to the stigma process. The structuring of the elements in the conceptual framework was based both on the findings of included works and the structure of existing conceptual frameworks of the determinants of stigma.

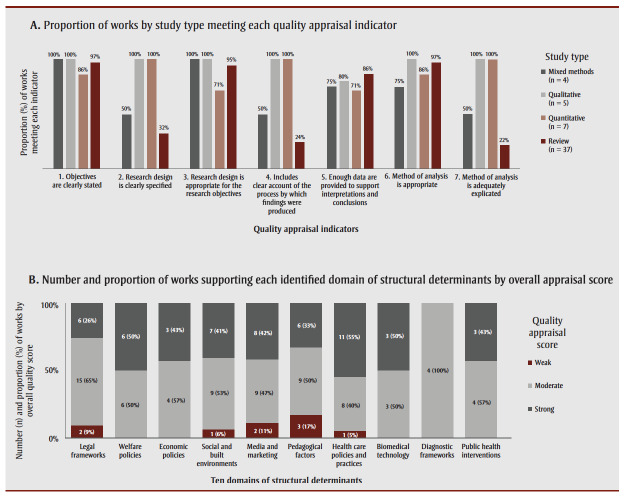

The third and final stage consisted of summarizing the methodological quality of the included works. In order to provide a quantitative synopsis of quality appraisal results for this review, we considered studies with less than four “Yes” responses (<60%) as weak, those receiving six or more “Yes” responses (>85%) as strong, and the remainder as moderate. As these thresholds have not been validated, full annotated scoring results were also provided to complement quantitative summaries.

Results

The results of the narrative synthesis are presented here, beginning with a descriptive summary of study characteristics, followed by a summary of identified structural determinants.

Descriptive results

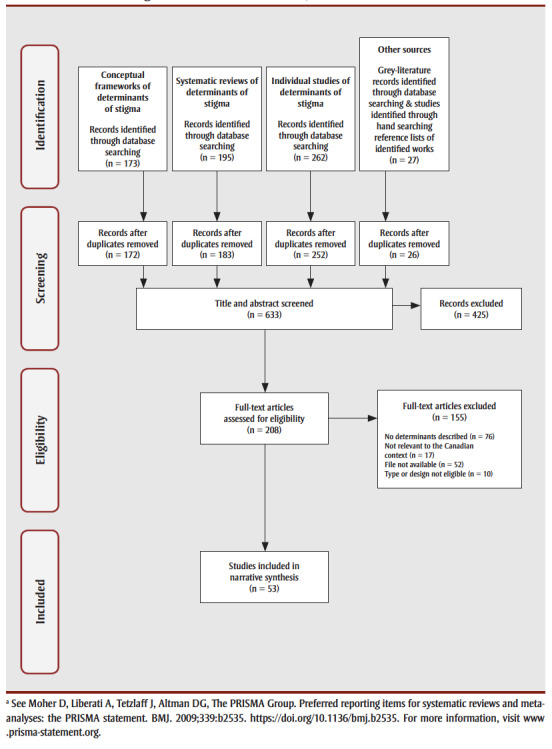

Study selection

Overall, 657 works were identified through the search strategy. Figure 1 provides a summary of works identified. Four works—all grey literature sources—were written in French. After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, 53 works were retained (Table 2). Most rejected works were those that did not document determinants of stigma that operate at a structural level. The retained works consisted of literature reviews (n=37; 69%), and individual mixed-method (qualitative and quantitative; n=4; 8%), qualitative (n=5; 9%) and quantitative (n=7; 13%) studies. Most reviews were not limited to a specific country setting, while individual studies were predominantly based in specific geographic regions including the United States (n=14), Canada (n=8) and Europe (n=5) (Table 2).

Figure 1. Flow diagram of data identification, selection and extraction.

Quality appraisal

Most publications were moderate or strong in quality. The weakest element of the publications was a lack of detail on the design processes by which findings and interpretations were produced (Table3). This element tended to be absent from works from the social sciences, which made up a large proportion of the included literature. This is a limitation of extant reviews of structural determinants of stigma. Figure 2A provides a summary of the mean score on each of the quality appraisal questions by study type, and Figure 2Bprovides an overview of the quality of works supporting each identified structural domain, described later on.

Figure 2. Summary of the quality appraisal assessment of identified works (N = 53), across study types and domains of structural determinants of stigma.

Study characteristics

The identified works overwhelmingly cited Link and Phelan’s1 conceptualization of stigma as a process driven by social, economic and political power inequities, through which attitudes, negative stereotypes and a sense of separation between groups can lead to discrimination and status loss. The reviewed literature explored many stigmatized experiences, identities, behaviours and health conditions (Table 2). Comprehensively, these were: individuals with mental health and substance use disorders;26-39 individuals living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)26,40-46 or other sexually transmitted or blood-borne infections (STBBI),47 tuberculosis (TB),48,49 diabetes,50 epilepsy,51 chronic pain52,53 or cancer—particularly types whose etiology may be attributable to patients’ behaviours;54 vulnerable subpopulations such as migrants and racialized communities;55,56 lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and other (LGBTQ+) populations;57,58 individuals experiencing poverty;59 sex workers;60 single mothers;61 individuals labelled as obese or fat;46,62 biological mothers of children diagnosed with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder;63 and individuals who smoke.64 Some authors highlighted that, although their research may have focussed on stigma pertaining to a specific condition or identity, individuals can experience multiple sources of stigma due to the intersection of multiple complex identities and life experiences.47,60 These authors acknowledged that restricted study scope could represent a potential limitation to their studies.

Lastly, among the works reviewed, 15 proposed conceptual frameworks that graphically represented at least one upstream determinant of stigma (Table 2).28,32,33,40-42,45-47,50,58,63,65-67 However, none were intended to provide a comprehensive summary of known structural determinants of stigma across populations. Identified frameworks were heterogeneous in form and content. However, most frameworks included an acknowledgement that stigma could be enacted at many levels, such as the individual (internalized), interpersonal, community, institutional and societal levels. Many frameworks also acknowledged that stigma is influenced by historical social inequities, such as those relating to systemic racism.46

Structural determinants of stigma

Thematic analysis of the reviewed literature yielded 10 overall domains of structural determinants of stigma (Table 2): (1)legal frameworks; (2)welfare policies; (3)economic policies; (4)social and built environments; (5)media and marketing; (6)pedagogical factors; (7)health care practices and policies; (8)biomedical technology; (9)diagnostic frameworks; and (10)public health interventions. A narrative synthesis of these domains and their relationship with stigma follows.

Legal frameworks

The domain of “legal frameworks” refers to factors pertaining to enacted or proposed legislation, including broad bills of rights, as well as downstream elements of criminal justice systems such as factors pertaining to policing, courts and corrections. Twenty-four works referenced terms that fell under this domain.29,31,32,34,35,43,45-48,51,54,56-58,60,61,66-72 Examples of terms describing structural determinants under this domain include (but are not limited to) “laws,”32 “legislative action,”43 “legal protections,”46 “Acts” (e.g. the United Kingdom’s Mental Health Act or Equality Act),35 “policing” and “sentencing.”45 Terms related to legal frameworks were mentioned in six existing frameworks.32,45-47,58,67

Overall, legal frameworks were identified as potential levers to prevent the discrimination and status loss components of the stigma process. Legislation that enshrines individual rights in relation to employment,57,60 housing,43 marriage,66,69 or immigration56—to name some of the areas referenced in reviewed works—can prevent inequitable access to health and social resources.67 On the other hand, factors relating to legal frameworks can also enable discrimination. This can occur when existing legislation fails to protect the rights of certain populations (people living with HIV are one prominent example43), when legislation restricts rights for certain groups (e.g. barring individuals with mental illnesses from serving on juries,34 or prohibiting individuals with epilepsy from driving51), or when components of the criminal justice system such as policing or sentencing affect certain populations more than others.46 The laws introduced during North America’s “War on Drugs,” referenced in several studies, are one of the most illustrative examples of the latter. These laws were described as influencing the stigma process by perpetuating negative stereotypes of individuals who committed drug-related crimes (e.g. using or selling illicit substances)34 and enabling status loss of Indigenous, Black and racialized communities through disproportionate policing and incarceration.45,66

Welfare policies

The domain of “welfare policies” refers to factors relating to the presence of, eligibility for and relative coverage or “generosity” of government-based structures, services and benefit programs that offer social, health or economic support for those in need. A non-exhaustive list of terms that led to the categorization of this domain included “welfare state,” “insurance,”33 “child welfare system,”40 “benefits”73 and “social security.”56 Twelve works used terms related to welfare policy,33,37,40,45,55,56,58,59,61,64,66,73 of which two also referred to these terms in proposed conceptual frameworks.33,40

Overall, the provision and coverage of social supports (or lack thereof) was noted across the included works as contributing to the stigma process via two principle mechanisms: by shaping societal beliefs about service or benefit recipients, and by influencing vulnerable populations’ access to protective and life-sustaining resources. Two examples of these welfare-related mechanisms include policies that disqualify individuals from welfare benefits or services based on certain statuses, such as those limiting immigrants’ eligibility for social services based on documentation status or length of time since immigration,56 and “War on Drugs” policies that disqualify offenders from social protections such as access to public housing.45 Both types of policies were identified as reinforcing negative societal perceptions of those who do not “merit” societal support, therefore legitimizing exclusion and negative stereotypes.33 Similar processes can occur if welfare coverage is restricted for certain conditions, such as when health insurance coverage is limited for mental health services37 or gender-affirming procedures,58 to name two examples. Policies that disqualify certain populations from access to social supports contribute to the stigma process by creating systematic gaps in care and status loss for affected populations.

Economic policies

The domain of “economic policies” refers to factors pertaining to governmental influence on features of economic landscapes, including policies relating to labour market wage, income redistribution policies or budgetary funding allocation across sectors. Though minimum wage limits are set through legislation, they are grouped under this domain because of their effects on economic conditions such as hiring practices and labour market participation—factors connected to the economic landscape of political jurisdictions.74 Eight works referred to terms pertaining to this domain,33,35,37,59,60,62,64,75 including one which integrated the concept of economic policies in its proposed conceptual framework.33 Examples of terms relating to this domain included “funding,”75 “tax,”37 “investment,”37 “economic development”33 and “minimum wage.”59

Overall, governmental influence on economic environments was described as influencing the stigma process by determining how equitably (or inequitably) economic resources are distributed within a population—thereby both influencing socioeconomic positioning of groups and sending the implicit message to disenfranchised groups that their disadvantaged state is not worth addressing through public investment. One example of how economic policies can influence status loss was that limited budgetary resource allocation to health services and workplace support programs for those experiencing mental health issues can lead to gaps in care and social and economic exclusion for those affected.35,37,75

Social and built environments

The domain of “social and built environments” refers to the characteristics of communities and places, at an aggregate level, in which individuals live, work or play—including population prevalence of certain health, social or economic conditions or elements of physical environments. Although they are likely influenced by elements that fall under preceding domains, such as economic or welfare policies, we consider socioecological environmental characteristics as a distinct domain. Seventeen works included terms pertaining to this domain,34,37,39,41,42,48,53,57,61,62,64,66,67,70,72,75-77 including three conceptual frameworks.41,42,66 A non-exhaustive list of terms relating to this domain included “environmental hazards,”66 “residential segregation,”42 “neighborhood disorder,”39 “prevalence” of a health or social condition (e.g. depression)75 and availability of social meeting “spaces.”41

Overall, studies describe how characteristics at the level of the local area and the community can influence the stigma process by contributing to both real and perceived social separation between groups and by generating social stratification in resource access. One example of these mechanisms is the way racialized and lower-income communities are segregated across residential neighbourhoods, which can reduce contact between stigmatized and nonstigmatized groups and reinforce perceptions of social differentiation.42,77 These exclusionary structures can contribute to economic deprivation,48 differential exposure to hazardous environmental conditions such as unsafe work conditions, pollution or infectious disease,66 and inequalities in access to health care facilities34 or places of education and employment for excluded groups.37 In contrast, social environments such as workplaces or residential areas with greater social diversity can foster more interactions between population subgroups, shift societal perceptions and beliefs and reduce inequities in resource access.67,75

Media and marketing

The domain of “media and marketing” refers to factors pertaining to the content development and regulation of communications strategies of various forms, such as news media, broadcasting or advertising, designed for the purposes of entertainment and sales, or to promote changes in individuals’ behaviours. Nineteen works used terms pertaining to this domain.27,28,32-37,48-50,54-56,60,61,67,76,77 Examples of terms relating to this domain included “media portrayals,”32 “media coverage,”37 “media context,”33 “commercial”67 and “social marketing.”50 Five of the identified conceptual frameworks explicitly mentioned media- and marketing-related terms.32,33,46,50,67

Media content and social marketing endeavours can influence the stigma process by shaping societal attitudes and beliefs, and by reinforcing or countering negative stereotypes, interpretations and attributions of blame. Media content can also serve as a proxy for social interaction with stigmatized groups. If direct contact with stigmatized populations is rare, media may act as the primary or sole source of information that impacts judgments made in everyday life about these individuals.32,77 To illustrate, one example is media portrayals of people with mental illnesses that depict these individuals as dangerous, unpredictable and criminal, thereby inciting fear and perceptions of social differentiation (or “othering”).27,28,37 Another example is media portrayals that reinforce beliefs that certain groups are to blame for the harms they experience, and are therefore less deserving of social support and inclusion.48,54,60 These narratives can legitimize discrimination towards marginalized groups.27,32,35,77

Media content can also reduce stigma by normalizing and promoting a greater understanding of certain behaviours or conditions.28,48 Media content presenting positive and inclusive messaging, and including factual information about the causes, treatments and experiences of individuals with mental illness, can shift population-level misconceptions and negative stereotypes.32

Pedagogical factors

The domain of “pedagogical factors” pertains to the structure, design and implementation of educational content (e.g. curricula) and teaching initiatives, as well as educational institutions. A sample of terms relating to this domain included “trainings,”58 “curricula”37 and “educational programs.”68 Eighteen works referenced terms that fell under this domain.29-32,34,37,38,40,43,46,50-53,55,58,68,72 Pedagogical factors were referenced in three conceptual frameworks.32,50,58

These works described how both the form and the content of educational material can influence the stigma process. Overall, much like media content, pedagogical factors can influence the stigma process by shaping societal attitudes and beliefs. Across studies, it was noted that pedagogical material that promotes or enables direct contact between the public and stigmatized individuals,38,50,51 that tackles misinformation32 including negative stereotypes29 and that normalizes stigmatized behaviours can reduce stigma by increasing awareness and empathy.

In contrast, the absence of training regarding certain health or social conditions can influence how care and services are delivered by professionals working in these fields, thereby contributing to discriminatory practices.38 One salient example is the way insufficient training among health care providers on HIV transmission risk can lead to insensitive and discriminatory practices towards patients living with HIV.43,55

Health care policies and practices

The domain of “health care policies and practices” refers to health system–level factors that pertain to the delivery of health care, including facility presence, accessibility and internal operational policies. Seventeen individual works referenced terms associated with this domain.26,28,31,33,34,37,40,41,44,45,48,49,55,60,64-66 Of these, five proposed conceptual frameworks that referenced terms relating to this domain.33,40,45,65,66 A non-exhaustive list of terms used included “health care system,”33 “linkage to care,”45 “healthcare quality”66 and “institutional [health care] protocols.”65

Overall, structural determinants relating to health care policies tended to fall under two categories: factors relating to the availability and relative accessibility of high-quality health care services, and factors pertaining to internal policies on health service organization and delivery. An example of the former is systemic differences in the availability of prompt,28,65 high-quality health care across communities, according to region of residence,40,66 financial capacity,44 and linguistic or cultural background.34 Examples of health care initiatives that may reduce stigma are programs that improve the accessibility of services, such as policies that help patients navigate health systems and adhere to treatment plans,44 and outreach activities (e.g. home visits) for underserved populations.40

Within clinical settings, institutional policies and structures can also contribute to discrimination against certain populations. Salient examples include physical structures, such as open-plan waiting rooms, and inter-staff communication policies that fail to protect patient’s confidentiality by allowing diagnoses to be overhead by others. These kinds of policies and structures can deter vulnerable populations from seeking care and can lead to the mistreatment of patients with stigmatized health conditions such as HIV55 or TB.48

Biomedical technology

The domain of “biomedical technology” refers to structural determinants that pertain to the development, existence, use and effects of technology or medical products that are provided to patients in clinical health settings to treat diagnosed health conditions. A sample of terms relating to this domain include “advent of effective treatment,”48 “control of disease”33 and “treatment side effects.”54 Six works—including one conceptual framework33—referenced determinants relating to this domain.26,33,48,54,78,79

Overall, studies documented how the existence of biomedical technologies that can prevent, manage or treat health conditions such as HIV,26 TB,48 or cancer,54 to name some examples, can influence the stigma process by changing the visibility of the condition, or by shifting societal beliefs around the dangerousness, severity and permanence of the disease as well as the risk of transmission. Studies also identified how the targeted promotion of biomedical treatments to certain populations because of their behaviours or risk profiles may lead to increased stigma. For example, guidelines that recommend that individuals engaging in riskier sexual activities use pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to prevent HIV infection may cause people to conflate the use of this technology with sexual promiscuity, resulting in potential and current users fearing and experiencing discrimination.26

Diagnostic frameworks

The domain of “diagnostic frameworks” refers to structural determinants that pertain to developments in the understanding of disease etiology and classification. Seven works described determinants that relate to this domain,33,35,46,50,58,63,79 two of which33,46 proposed a conceptual framework that referenced terms relating to this domain. Examples of terms falling under this domain included “diagnostic practices,”63 “DSM” (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders),79 “genetic causal information”50 and “medicalization.”58

Overall, developments in societal understanding of how diseases emerge can contribute to the stigma process by influencing societal perceptions of where responsibility for disease emergence should be placed. One example of this has been research findings that certain conditions such as mental health disorders or diabetes can be linked to underlying genetic factors. These developments in scientific knowledge can shift how societies attribute blame for incidence of these conditions.33,50

Developments in societal understanding of how health and social conditions should be classified can contribute to the stigma process by influencing perceptions of what is considered abnormal. By labelling certain conditions as “disorders” or “diseases,” clinical diagnoses can imply the need for corrective treatment and facilitate the ostracizing of affected individuals. One illustrative example is how previous editions of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) pathologized homosexuality and gender nonconformity, contributing to negative stereotypes of and discrimination against LGBTQ+ communities.58

Public health interventions

The domain of “public health interventions” refers to policies, programs and initiatives led or mandated and financially supported by public health stakeholders. Seven works, including one conceptual framework,50 described determinants relating to this domain.42,49,50,60,63,67,77 Terms used in these studies included “health promotion initiatives,”50 “public health initiatives”63 and “community-based outreach interventions.”42

Overall, studies described how public health interventions can influence the stigma process by shaping societal norms and beliefs both positively and negatively. For example, health promotion interventions that perpetuate messaging around the need to change certain individual behaviours (e.g. weight control, substance consumption) can have unintentional negative influences on societal beliefs by reinforcing narratives of blame and responsibility for individuals engaging in these behaviours or experiencing resulting health conditions.26,50 One illustration of this was public health messaging of zero-tolerance of alcohol consumption during pregnancy. This messaging can perpetuate negative societal beliefs of pregnant individuals who drink or of mothers of children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, and can lead to hesitancy among pregnant individuals who do drink to consult health and social services.63

Community-based public health interventions can also influence the discrimination and status loss components of the stigma process by intervening on resource distribution. One example of such interventions is community-based public health initiatives designed to improve access to health and harm reduction services for populations that may have less trust in medical establishments due to historical discrimination, such as individuals living with HIV or sex workers.42,60 These types of interventions are believed to be protective against stigma as they promote respect and inclusivity, and represent sources of empowerment for vulnerable populations.42

Conceptual framework

The ten domains of structural determinants are summarized in Figure 3. This figure is a simplified conceptual framework that depicts the structural determinant domains identified in the reviewed literature, and how they were described in relation to the stigma process as defined by Link and Phelan.1 Three large arrows flow from the structural determinants to the stigma process. These arrows indicate how structural factors can influence the stigma process overall, and more precisely by shaping the psychosocial “drivers” of the stigma process, which include societal beliefs and stereotypes based in fear, normative judgment or blame as well as lived experiences of discrimination and status loss.3,72

Figure 3. Conceptual framework of identified domains of structural determinants and their relationship with the stigma process.

In line with the reviewed conceptual frameworks and models, including the CPHO’s Stigma Pathways Model,3 Figure 3. also includes a graphical representation of the levels of population interaction at which stigma can be enacted, from the individual (internalized) to the systems level. Further, many studies and existing frameworks acknowledged that stigma processes are influenced by historical social inequities and discrimination,3,46,72 thus creating feedback loops between structural practices and stigma processes through time. To represent these dynamics, Figure 3. includes a large arrow that flows from the stigma process back to structural determinants.

Since this review did not involve an exhaustive literature search and further research is needed to confirm both the causal associations between factors and the effectiveness of various stigma-reduction interventions across populations and settings, Figure 3. should not be interpreted as providing a comprehensive summary of all possible structural determinant domains, nor as depicting firm causal ties between each of the domains and elements of the stigma process. Instead, it was designed to provide a visual summary of the narrative synthesis presented in this review that can be used as a tool to structure policy discussions on ways to orient public health interventions to reduce stigma in Canada and abroad.

Discussion

This rapid review was designed to identify and summarize structural determinants of stigma in Canada and other OECD settings, in order to guide future research and intervention. An analysis of findings from 53 works from peer-reviewed and grey-literature sources, 15 of which included proposed conceptual frameworks that mentioned at least one type of structural determinant of stigma, this review is the first known summary and conceptual framework of structural determinants of stigma across health and social conditions. Applying a thematic analysis of structural-level factors documented in the literature, we identified and defined 10distinct domains of structural determinants of stigma. These domains were legal frameworks, welfare policies, economic policies, social and built environments, media and marketing, pedagogical factors, health care practices and policies, biomedical technology, diagnostic frameworks, and public health interventions.

This summary fills an important gap in the existing literature by bringing together findings from a wide range of fields of stigma research, and elucidating types of factors that operate at the contextual level to influence societal beliefs, negative stereotypes, discrimination or status loss across multiple social contexts and populations.14 This review and the proposed conceptual framework are tools that can be used to structure future policy conversations; the ten domains of factors and the governance sectors to which they relate can be systematically considered when seeking to address and prevent stigma. As structural-level factors can contribute to social stratification and health inequities,9 each identified domain merits attention.

Strengths and limitations

One strength of this rapid review is its focus on determinants of stigma across health outcomes and physical or social attributes. The resulting summary is therefore applicable to a wide range of substantive domains of public health and social policy. Another strength is its focus on structures that could theoretically be modified through intersectoral public health intervention, with potential population-level impacts on the stigma process.9,15

Nonetheless, this review has certain limitations. Due to the non-exhaustive search strategy of the rapid review design, relevant studies—particularly individual qualitative or quantitative studies—may have been missed by our search strategy, and thus, certain examples of structural determinants may have been missed as well. However, given that the majority of published works included in this review are evidence summaries and frameworks of structural determinants, we expect that the contribution of missed studies is likely to be minimal.

Another limitation is that many of the works reviewed here did not include sufficient detail about the process by which their results were obtained and synthesized. The opacity of the data-generating process of these works calls into question the comprehensiveness of their findings. The resulting summary should therefore be used primarily as a conceptual guide rather than an exhaustive review. Including this element in future texts will be a necessary step for strengthening public health literature on stigma.

Finally, this review summarizes findings for the general context of OECD nations. We did not seek to explore structural determinants within a specific jurisdiction. Since the impacts of structural determinants on the stigma process may be heterogeneous across local contexts, future research and policy conversations on ways to address stigma should consider how local eco-social or political environments may influence the structural determinants of stigma or the effects of potential interventions on stigma reduction.

Conclusion

This review complements previously published summaries of the influence of stigma as a determinant of health. Here, the structural determinants of stigma as a social outcome occurring across health and social conditions were explored. A rapid review of existing evidence suggests that there are at least ten domains of structural determinants of stigma. The present review’s conceptual framework of these domains can be used as a tool to structure future policy conversation across sectors on ways to reduce stigma at a population level.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Lisa Glandon and the Information and Knowledge Management Division from the Health Canada Library, as well as Dr. Kimberly Gray, Michle Boileau-Falardeau and Dr. Louis Turcotte for their contributions and feedback.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Authors’ contributions and statement

All authors contributed to the methodological design of the literature review. AB and BHMF conducted the literature review search and identified relevant works. All authors extracted data, analyzed identified works and drafted the article. AB and CBF revised the article.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.

References

- Link BG, Phelan JC, et al. Conceptualizing stigma. Annu Rev Sociol. 2001;27((1)):363–85. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Phelan JC, Link BG, et al. Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. Am J Public Health. 2013;103((5)):813–21. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam T, et al. Government of Canada. Ottawa(ON): Addressing stigma: towards a more inclusive health system. [Google Scholar]

- Major B, Dovidio JF, Link BG, Calabrese SK, Major B, Dovidio JF, Link BG, et al. Stigma and its implications for health: introduction and overview. Oxford University Press. :3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Stangl AL, Earnshaw VA, Logie CH, et al, et al. The Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework: a global, crosscutting framework to inform research, intervention development, and policy on health-related stigmas. BMC Med. 2019;17((1)):31–28. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1271-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehlert S, Sohmer D, Sacks T, Mininger C, McClintock M, Olopade O, et al. Targeting health disparities: a model linking upstream determinants to downstream interventions. Targeting health disparities: a model linking upstream determinants to downstream interventions. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27((2)):339–49. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayer J, et al. Structural stigma and health for persons with mental illness [thesis] [Chicago (IL)]: University of Illinois at Chicago; 2018. 2018 Available from: https://indigo.uic.edu/articles/thesis/Structural_Stigma_and_Health_for_Persons_with_Mental_Illness/10854335. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, et al. Structural stigma and health inequalities: research evidence and implications for psychological science. Am Psychol. 2016;71((8)):742–51. doi: 10.1037/amp0000068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solar O, Irwin A, et al. World Health Organization. Geneva(CH): 2007. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon K, Goldenberg SM, Deering KN, Strathdee SA, et al. HIV infection among female sex workers in concentrated and high prevalence epidemics: why a structural determinants framework is needed. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2014:174–82. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux AV, Aiello AE, et al. Multilevel analysis of infectious diseases. J Infect Dis. 2005;191((Suppl_1)):S25–S33. doi: 10.1086/425288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood M, Leeuw S, Lindsay NM, Reading C, et al. Canadian Scholars’ Press. Toronto(ON): 2015. Determinants of Indigenous peoples’ health. [Google Scholar]

- Knight RE, Shoveller JA, Carson AM, Contreras-Whitney JG, et al. Examining clinicians’ experiences providing sexual health services for LGBTQ youth: considering social and structural determinants of health in clinical practice. Health Educ Res. 2014;29((4)):662–70. doi: 10.1093/her/cyt116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan J, et al. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav. 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, Kawachi I, Glymour MM, nd ed, et al. Social epidemiology. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Khangura S, Konnyu K, Cushman R, Grimshaw J, Moher D, et al. Evidence summaries: the evolution of a rapid review approach. Syst Rev. 2012 doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganann R, Ciliska D, Thomas H, et al. Expediting systematic reviews: methods and implications of rapid reviews. Implement Sci. 2010;5((1)):56–70. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbins M, et al. National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools. Hamilton(ON): 2017. Rapid review guidebook: steps for conducting a rapid review. [Google Scholar]

- a E, Valero M, Sicilia J, et al. Comparative study of journal selection criteria used by MEDLINE and EMBASE, and their application to Spanish biomedical journals. Primo Pea E, Vzquez Valero M, Garca Sicilia J [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T, Peacock R, et al. Effectiveness and efficiency of search methods in systematic reviews of complex evidence: audit of primary sources. BMJ. 2005;331((7524)):1064–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38636.593461.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Woods M, Cavers D, Agarwal S, et al, et al. Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Med Res Methodology. 2006 doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-6-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: a product from the ESRC Methods Programme (Version 1) Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: a product from the ESRC Methods Programme (Version 1). Lancaster (UK): Lancaster University. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- Guest G, MacQueen KM, Namey EE, et al. Applied thematic analysis. Sage Publications. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V, et al. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psych. 2006;3((2)):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan GW, Bernard HR, et al. Techniques to identify themes. Field Methods. 2003:85–109. [Google Scholar]

- Golub SA, et al. PrEP stigma: implicit and explicit drivers of disparity. PrEP stigma: implicit and explicit drivers of disparity. Curr HIV/ AIDS Rep. 2018;15((2)):190–7. doi: 10.1007/s11904-018-0385-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nairn R, Coverdale S, Coverdale JH, et al. A framework for understanding media depictions of mental illness. Acad Psychiatry. 2011;35((3)):202–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.35.3.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukolo A, Heflinger CA, Wallston KA, et al. The stigma of childhood mental disorders: a conceptual framework. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49((2)):92–103. doi: 10.1097/00004583-201002000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arboleda-Florez J, Stuart H, et al. From sin to science: fighting the stigmatization of mental illnesses. Can J Psychiatry. 2012;57((8)):457–63. doi: 10.1177/070674371205700803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holder SM, Peterson ER, Stephens R, Crandall LA, Health J, et al. Stigma in mental health at the macro and micro levels: implications for mental health consumers and professionals. Community Ment Health J. 2019;55((3)):369–74. doi: 10.1007/s10597-018-0308-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonsack C, Morandi S, Favrod J, Conus P, et al. Le stigmate de la folie: de la fatalit au rtablissement. Rev Med Suisse. 2013;9((377)):588–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Wong EC, Cerully JL, Schultz D, Eberhart NK, Health Q, et al. Interventions to reduce mental health stigma and discrimination: a literature review to guide evaluation of California’s mental health Prevention and Early Intervention initiative. Rand Health Q. 2013;2((4)):3–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido BA, Martin JK, Lang A, Olafsdottir S, et al. Rethinking theoretical approaches to stigma: a Framework Integrating Normative Influences on Stigma (FINIS) Soc Sci Med. 2008:431–40. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The National Academies Press. Washington(DC): 2016. Ending discrimination against people with mental and substance use disorders: the evidence for stigma change. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams B, et al. The journey to self-stigma and its impact on ‘recovery’ in people experiencing mental distress: fighting back with stigma resistance. J Undergrad Res NTU. 2018;1((1)):283–303. [Google Scholar]

- Clement S, Lassman F, Barley E, et al. Mass media interventions for reducing mental health‐related stigma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;7((7)):CD009453–303. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009453.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston JD, et al. Mental Health Commission of Canada. Ottawa(ON): 2013. Mental illness-related structural stigma: the downward spiral of systemic exclusion. [Google Scholar]

- La lutte contre la stigmatisation et la discrimination dans le rseau de la sant et des services sociaux - guide d’accompagnement. Governement du Qubec. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Min SY, Psychiatr Q, et al. Association between community contextual factors and stigma of mental illness in South Korea: a multilevel analysis. Psychiatr Q. 2017;88((4)):853–64. doi: 10.1007/s11126-017-9503-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodgate RL, Zurba M, Tennent P, Cochrane C, Payne M, Mignone J, et al. “People try and label me as someone I’m not”: the social ecology of Indigenous people living with HIV, stigma, and discrimination in Manitoba, Canada. Soc Sci Med. 2017:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- France NF, Mcdonald SH, Conroy RR, et al, et al. “An unspoken world of unspoken things”: a study identifying and exploring core beliefs underlying self-stigma among people living with HIV and AIDS in Ireland. Swiss Med Wkly. 2015:w14113–24. doi: 10.4414/smw.2015.14113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw VA, Bogart LM, Dovidio JF, Williams DR, et al. Stigma and racial/ethnic HIV disparities: moving toward resilience. Stigma Health. 2015;1((S)) doi: 10.1037/a0032705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darlington CK, Hutson SP, et al. Understanding HIV-related stigma among women in the Southern United States: a literature review. AIDS Behav. 2017:12–26. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1504-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz IT, Ryu AE, Onuegbu AG, et al, et al. Impact of HIV-related stigma on treatment adherence: systematic review and meta-synthesis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16((3 Suppl 2)):18640–26. doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.3.18640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr J, Jackson T, et al. Stigma, sexual risks, and the war on drugs: examining drug policy and HIV/AIDS inequities among African Americans using the Drug War HIV/AIDS Inequities Model. Int J Drug Policy. 2016:31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clair M, Daniel C, Lamont M, et al. Destigmatization and health: cultural constructions and the long-term reduction of stigma. Soc Sci Med. 2016:223–32. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean R, et al. Resources to address stigma related to sexuality, substance use and sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections. Can Comm Dis Rep. 2018;44((2)):62–7. doi: 10.14745/ccdr.v44i02a05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coreil J, Mayard G, Simpson KM, Lauzardo M, Zhu Y, Weiss M, et al. Structural forces and the production of TB-related stigma among Haitians in two contexts. Soc Sci Med. 2010:1409–17. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig GM, Daftary A, Engel N, O’Driscoll S, Ioannaki A, et al. Tuberculosis stigma as a social determinant of health: a systematic mapping review of research in low incidence countries. Int J Infect Dis. 2017:90–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schabert J, Browne JL, Mosely K, Speight J, et al. Social stigma in diabetes: a framework to understand a growing problem for an increasing epidemic. Patient. 2013;6((1)):1–10. doi: 10.1007/s40271-012-0001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes PT, Snape DA, Beran RG, Jacoby A, et al. Epilepsy stigma: what do we know and where next. Epilepsy Behav. 2011;22((1)):55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2011.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruddere L, Craig KD, et al. Understanding stigma and chronic pain: a state-of-the-art review. Pain. 2016:1607–10. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aste JA, et al. Chronic pain and stigma: a literature review [dissertation] Chronic pain and stigma: a literature review [dissertation]. [Ohio]: Union Institute and University; 2016; 10113719. 2016 Available from: https://pqdtopen.proquest.com/doc/1801982335.html?FMT=AI. [Google Scholar]

- Knapp S, Marziliano A, Moyer A, et al. Identity threat and stigma in cancer patients. Health Psychol Open. 2014:2055102914552281–10. doi: 10.1177/2055102914552281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrey AE, Bilsen J, Lacor P, Deschepper R, et al. Perceptions of stigma and discrimination in health care settings towards sub-Saharan African migrant women living with HIV/AIDS in Belgium: a qualitative study. J Biosoc Sci. 2017:578–96. doi: 10.1017/S0021932016000468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey BN, et al. Mechanisms by which anti-immigrant stigma exacerbates racial/ethnic health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2018;108((4)):460–3. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, et al. Structural stigma and the health of lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2014;23((2)):127–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hughto JM, Reisner SL, Pachankis JE, et al. Transgender stigma and health: a critical review of stigma determinants, mechanisms, and interventions. Soc Sci Med. 2015:222–31. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Les facteurs engendrant l’exclusion au Canada: survol de la littrature multidisciplinaire. Centre d’tude sur la pauvret et l’exclusion. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Benoit C, Jansson SM, Smith M, Flagg J, et al. Prostitution stigma and its effect on the working conditions, personal lives, and health of sex workers. J Sex Res. 2018;55((4-5)):457–71. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2017.1393652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll NJ, et al. Lone mothers’ experiences of stigma: a comparative study [doctoral thesis] [Huddersfield, UK]: University of Huddersfield; 2017. 2017 Available from: http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/34358/1/FINAL%20THESIS%20-%20Carroll.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Brewis AA, et al. Stigma and the perpetuation of obesity. Soc Sci Med. 2014:152–8. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell E, Andrew G, Pietro N, Chudley A, Reynolds J, Racine E, et al. It’s a shame. Pub Health Ethics. 2016:65–77. [Google Scholar]

- Stuber J, Galea S, Link BG, et al. Smoking and the emergence of a stigmatized social status. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67((3)):420–430. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson B, Hirsch G, Andres K, et al. Structural factors that promote stigmatization of drug users with hepatitis C in hospital emergency departments. Int J Drug Policy. 2013;24((5)):471–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudoir SR, Earnshaw VA, Andel S, et al. “Discredited” versus “discreditable”: understanding how shared and unique stigma mechanisms affect psychological and physical health disparities. Basic Appl Soc Psych. 2013;35((1)):75–87. doi: 10.1080/01973533.2012.746612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirabito AM, Otnes CC, Crosby E, et al, et al. The stigma turbine: a theoretical framework for conceptualizing and contextualizing marketplace stigma. J Public Policy Mark. 2016;35((2)):170–84. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson NL, Dressler WW, et al. Medical disease or moral defect. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2017;41((4)):480–98. doi: 10.1007/s11013-017-9531-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, Hatzenbuehler ML, Berg RC, et al, et al. Anti-LGBT and anti-immigrant structural stigma: an intersectional analysis of sexual minority men’s HIV risk when migrating to or within Europe. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;76((4)):356–66. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Corliss HL, Austin SB, et al. Structural stigma and sexual orientation disparities in adolescent drug use. Addict Behav. 2015:14–18. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Pachankis JE, North Am, et al. Stigma and minority stress as social determinants of health among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: research evidence and clinical implications. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2016;63((6)):985–97. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link B, Hatzenbuehler ML, et al. Stigma as an unrecognized determinant of population health: research and policy implications. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2016;41((4)):653–73. doi: 10.1215/03616878-3620869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen H, Bourgois P, Drucker E, et al. Pathologizing poverty: new forms of diagnosis, disability, and structural stigma under welfare reform. Soc Sci Med. 2014:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumark D, et al. The econometrics and economics of the employment effects of minimum wages: getting from known unknowns to known knowns. Ger Econ Rev. 2019;20((3)):293–329. [Google Scholar]

- Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H, Link BG, Schomerus G, et al. Public attitudes regarding individual and structural discrimination: two sides of the same coin. Soc Sci Med. 2014:60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- sy M, Filiatrault F, et al. Dimension thique de la stigmatisation en sant publique: outil d’aide la rflexion. Institut national de sant publique du Qubec. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Phelan JC, Lucas JW, Ridgeway CL, Taylor CJ, et al. Stigma, status, and population health. Soc Sci Med. 2014:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringer KL, Turan B, McCormick L, et al, et al. HIV-related stigma among healthcare providers in the Deep South. AIDS Behav. 2016;20((1)):115–25. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1256-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorm AF, Griffiths KM, et al. The public’s stigmatizing attitudes towards people with mental disorders: how important are biomedical conceptualizations. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;118((4)):315–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]