Abstract

Consuming polyphenol-rich fruits and vegetables, including blueberries, is associated with beneficial health outcomes. Interest in enhancing polyphenol intakes via dietary supplements has grown, though differences in fruit versus supplement matrix on gut microbiota and ultimate phenolic metabolism to bioactive metabolites are unknown. To evaluate this, 5-month-old, ovariectomized, Sprague-Dawley rats were gavaged for 90d with a purified extract of blueberry polyphenols (0, 50, 250, or 1000 mg total polyphenols/kg bw/d) or lyophilized blueberries (50 mg total polyphenols/kg bw/d, equivalent to 250 g fresh blueberries/d in humans). Urine, feces, and tissues were assessed for gut microbiota and phenolic metabolism. Significant dose- and food matrix-dependent effects were observed at all endpoints measured. Gut microbial populations showed increased diversity at moderate doses but decreased diversity at high doses. Urinary phenolic metabolites were primarily observed as microbially derived metabolites and underwent extensive host xenobiotic phase II metabolism. Thus, blueberry polyphenols in fruit and supplements induce differences in gut microbial communities and phenolic metabolism, which may alter intended health effects.

Keywords: Blueberry, polyphenol metabolism, gut microbiota, dose-response, food matrix

Graphical Abstract

Metabolism of orally dosed blueberry polyphenols is dependent upon both dose and food matrix, resulting in different compositions of phenolic metabolites and the gut microbiota.

1. INTRODUCTION

Polyphenols are secondary plant metabolites present in fruits and vegetables that may have health benefits when consumed regularly. As a common component of typical diets containing fruits and vegetables, polyphenols reduce oxidative stress and inflammation,1 leading to improved cardiovascular and neurocognitive function2, 3 as well as decreased incidence of many chronic diseases.4, 5 Blueberries are a particularly rich source of dietary polyphenols and have been specifically associated with numerous health benefits in both human and animal studies.6–8

As a first step towards elucidating the potential connections between blueberry polyphenols and health benefits, understanding their metabolism and bioavailability is key. Ingested polyphenols enter the upper intestine, where a small portion (<2% of total dose) is absorbed and typically undergoes host xenobiotic phase II metabolism.9–11 Unabsorbed phenolics pass to the lower gut, where they are exposed to the gut microbiota. Polyphenols serve as a microbial feedstock, being catabolized by the gut microbiota to smaller molecular weight phenolic acids. This may shift microbial populations to compositions associated with beneficial health outcomes and enable the absorption and further host xenobiotic phase II metabolism of specific microbial phenolic acid metabolites.11–14 Importantly, microbially-generated metabolites are reported to be absorbed at significantly higher levels than upper GI metabolites and may be responsible for the health benefits associated with consuming polyphenols.10, 15

In recent years, there has been a rapid rise in the consumption of herbal and botanical dietary supplements, as consumers seek to maximize the health benefits attributed to fruit and vegetable derived polyphenols.16, 17 Dietary supplements contain high doses of purified polyphenol extracts, which may alter polyphenol metabolism and the gut microbiota in two key ways: 1) the increased dose, resulting in higher GI concentrations of phenolics, and 2) the absence of the food matrix, which includes many components typically considered substrates for microbial communities including dietary fiber.18

In a recent study, we examined the acute pharmacokinetics of blueberry phenolics following administration of a single dose of purified blueberry polyphenols typical of common dietary supplements.19 Using an ovariectomized (OVX) rat model, we observed dose-dependent shifts in metabolism, especially for microbially-generated metabolites, suggesting that even a single dose may result in significant dose-dependent differences in physiological profiles of relevant metabolites. To address whether these metabolic shifts are transient or persist with repeated dosing, the present study measured the metabolism of escalating doses of blueberry phenolics as well as changes in the gut microbiota over 90 days in an OVX rat model. This study was part of a classical toxicity study, in which we demonstrated that high doses of blueberry polyphenols are safe over 90d.20 We hypothesized that repeated intake of blueberry polyphenols over 90d would exert dose- and food matrix-dependent effects on gut microbial populations and, subsequently, phenolic metabolism.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Chemicals Materials and vendors

Commercial standards of cyanidin-3-O-glucoside chloride, malvidin-3-O-glucoside chloride, peonidin-3-O-glucoside chloride, petunidin-3-O-glucoside chloride, gallic acid, caffeic acid, ferulic acid, ethyl gallate, taxifolin, chlorogenic acid, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, 3-hydroxybenzaldehyde, hippuric acid, 3-hydroxyhippuric acid, isovanillin, 4-hydroxyphenylacetic acid, 3-hydroxyphenylpropionic acid, 3-methoxyphenylacetic acid, vanillic acid, homovanillic acid, syringic acid, quercetin, myricetin, quercetin-3-O-glucuronide, 4-methoxyquerceting, p-coumaric acid, epicatechin, kaempferol, and quercetin-3-O-rutinoside as well as sodium carbonate and Folin and Ciocalteu’s reagent (2N) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Extraction and LC-MS grade solvents, including methanol, water, acetonitrile, hexanes, and formic acid were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). VitaBlue Pure American Blueberry Extract was obtained from FutureCeuticals (Momence, IL, USA); lyophilized composite wild blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium) powder was obtained from the Wild Blueberry Association of North America (Old Towne, ME, USA).

2.2. Animal protocols

2.2.1. Study overview.

As described previously,20 five-month old, virgin, OVX, female Sprague-Dawley rats were used to mimic osteoporosis related bone loss in postmenopausal females, who are the most frequent consumers of botanical dietary supplements16 and to align with the overall project goal of assessing the impact of blueberry polyphenols in this population. Upon arrival, rats were randomized to treatment groups and given one month to stabilize from ovariectomy. Animals then underwent 90d of dosing via oral gavage. Urine was collected throughout the study to monitor phenolic metabolism, while feces were collected at baseline and end of study to analyze gut microbiota. Twenty-four hours after the last dose was administered, animals were euthanized and tissues collected for analysis of phenolic tissue distribution.

2.2.2. Animal care.

Animal experiments were conducted in adherence to Purdue University Animal Care and Use Committee (PACUC) guidelines, following an approved protocol (1808001790). Rats were purchased from Envigo (Indianapolis, IN, USA) and individually housed in stainless steel, wire-bottom cages in a temperature and humidity-controlled room with a 12h light/dark cycle and ad libitum access to food and water.

2.2.3. Treatment groups.

A total of 5 treatment groups (n=10/gp) were used in this study. Treatment groups received an oral gavage of either purified blueberry polyphenols containing 0, 50, 250, or 1000 mg total polyphenols/kg bw/d (designated water, low, medium, and high, respectively) or lyophilized, whole blueberries containing 50 mg total polyphenols/kg bw/d (designated BB). The low and BB doses correspond to an adult human consuming 250 g of fresh blueberries per day (i.e., a “dietary dose”, calculated using the FDA’s rat to human conversion factor21), with the medium and high dose groups 5- and 20-fold higher, respectively, to mimic higher doses of polyphenols as may be present in dietary supplements.

2.2.4. Non-gavage control group.

In addition to the 5 treatment groups, a smaller group of animals (n=4) was maintained throughout the study and subjected to all study procedures with the exception of oral gavage. These animals were monitored to detect potential adverse effects of daily oral gavage distinct from blueberry polyphenol treatment-related effects. As we reported previously, no adverse effects of daily oral gavage were observed.20

2.2.5. Diets.

For the duration of the study, all animals were fed polyphenol-free diets. These diets were based on the AIN-93M diet, using corn oil in place of soybean oil to remove isoflavones and minimize confounding by polyphenols unrelated to blueberry treatment. Diets were prepared by Research Diets (New Brunswick, NJ, USA).

2.2.6. Oral gavage dose preparation and administration.

The low, medium, and high dose groups were orally gavaged with a slurry of concentrated blueberry phenolic extracts (26.7% total phenolics (w/w)) in water. The BB group was orally gavaged with a slurry of lyophilized, whole blueberries (3.52% total phenolics (w/w)) in water. All gavage doses were administered shortly after “lights on” each day (approximately 0800-1000), with the gavage needle dipped in a sugar solution (0.5 g/mL) to minimize stress and induce swallowing.22

2.2.7. Urine and fecal collection.

On days 0, 7, 15, 30, 60, and 90, 24h urine was collected. On each of these days, animals were given their daily oral gavage dose and then placed in metabolic cages for 24h to collect excreta. Urine was centrifuged to remove food spill and debris, acidified to a final concentration of 0.1% formic acid, blanketed with nitrogen, and frozen at −80°C until analysis. Feces were collected using metabolic cages at baseline and end of study, placed in centrifuge tubes, and immediately frozen at −80°C until analysis.

2.2.8. Tissue collection.

Animals were euthanized via CO2 asphyxiation 24h after receiving the final oral gavage dose. Immediately after sacrifice, animals were perfused with 200 mL saline to clear blood from tissues and eliminate possible confounding of polyphenol analyses. Then, small intestine and colon were harvested and flushed with 3x10mL saline before being snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until analysis, while brain, liver and kidney were snap frozen immediately and stored at −80°C until analysis. Ovariectomy was verified visually for all animals.

2.3. Microbiota extraction and analysis.

2.3.1. Fecal DNA extraction and amplicon sequencing.

Microbiota analysis was completed on fecal samples from all rats at day 0 and day 90. DNA was extracted from frozen fecal pellets using the FastDNA SPIN Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals) and bead-beating, following the procedure from the manufacturer. Agarose gels, spectrometry and fluorometry were used to determine DNA quality and quantity, as previously described.23 The V3 (343F: TACGGRAGGCAGCAG) to V4 (804R: CTACCRGGGTATCTAATCC) region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified via PCR using the Illumina step out protocol, as previously described.23 Sequencing was performed on the products using MiSeq Illumina 2 x 250 paired end sequencing.

2.3.2. Sequence analysis.

Sequences were analyzed using the QIIME pipeline version 2-2020.2.24 Sequences were paired, trimmed for quality, and sorted into representative sequences using DADA2.25 A taxonomy classifier was trained using the SILVA dataset (version 132_99). Representative sequences were assigned taxonomies with this classifier. Diversity-based analyses were conducted on samples rarified to the same sampling depth, chosen to maximize features retained while minimizing samples lost. Three samples (BB d0, high d90, and non-gavage d90) were excluded due to the selected sampling depth of 4197 reads. Alpha diversity was analyzed using Faith’s phylogenetic diversity (PD), Shannon, observed operational taxonomic units (OTUs), and Pielou’s evenness. Beta diversity was analyzed using Bray-Curtis, Jaccard, and weighted and unweighted Unifrac.26

2.4. Polyphenol analyses

2.4.1. Extraction and purification of phenolics in starting materials, animal diet, and oral gavage preparations.

Lyophilized whole blueberries, purified blueberry extract, animal diets, and solutions for oral gavage were extracted in triplicate and subsequently purified via solid phase extraction (SPE) using Oasis HLB 1cc extraction cartridges (Waters, Milford, MA, USA), as described elsewhere.27 Random samples of oral gavage doses were taken every 10d throughout the study to monitor for potential polyphenol degradation. These samples were analyzed for total phenolics and, when necessary, adjustments made to ensure accurate dosing throughout the study.

2.4.2. Extraction and purification of urine polyphenol metabolites.

Phenolics were extracted and purified via SPE using strataX, polymeric reversed phase microelution 96 well plate with a capacity of 2 mg/well (Phenomenex, Torrence, CA, USA) using previously described methods.19

2.4.3. Extraction and purification of tissue polyphenol metabolites.

Polyphenols and their metabolites were extracted from 0.5-1 g samples of brain, liver, kidney, small intestine, and colon, based on previously described methods.28 Briefly, tissues were defatted by homogenizing with 5 mL hexanes and vortex mixed 10 min. The resulting slurry was centrifuged for 10 min at 3000 g, and the supernatant discarded. Samples were then extracted with 5 mL 1% formic acid in methanol, being vortexed 10 min and centrifuged 10 min at 3000 g. The resulting supernatant was transferred to a clean test tube and the extraction repeated; supernatants were combined, dried under nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until analysis.

Tissue extracts were resolubilized with 2 mL 2% formic acid in water. This mixture was diluted 1:1 with 1% formic acid in water, before loading 200 μL onto preconditioned SPE plate. Samples were washed, dried, and eluted following the same procedures used for urine samples.

2.4.4. Quantification of phenolics and phenolic metabolites.

Total phenolics were quantified in crude extracts via the Folin method and corrected for vitamin C interferences as described elsewhere.29 Individual phenolics were quantified via UPLC-MS/MS using the same instrument, column, and solvent gradient described previously for our acute study.19 Phenolic content of starting materials, diets, and gavage doses are shown in Table 1. Phenolic metabolites in urine and tissue samples were similarly analyzed, with specific Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) transitions used to capture metabolites not present in starting materials.

Table 1 –

Polyphenol content of starting materials and oral gavage doses.a

| (Poly)phenol | Raw Materials (mg/100 g) | Gavage Doses (mg/kg bw) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FD | CE | Water | Low | Medium | High | BB | |

| Total Phenolics b | 3517 ± 54.8 | 26715 ± 384 | nd | 50.0 ± 3.77 | 253 ± 6.07 | 1000 ± 18.4 | 50.8 ± 7.47 |

| Anthocyanins | |||||||

| Cyanidins | |||||||

| Arabinoside | 21.4 ± 0.30 | 93.8 ± 14.9 | nd | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.54 ± 0.04 | 2.27 ± 0.23 | 0.23 ± 0.07 |

| Galactoside + Glucoside | 46.3 ± 0.50 | 126 ± 12.2 | nd | 0.44 ± 0.04 | 2.09 ± 0.17 | 8.98 ± 0.82 | 1.00 ± 0.30 |

| Delphinidins | |||||||

| Arabinoside | 20.8 ± 0.37 | 301 ± 50.4 | nd | 0.35 ± 0.05 | 1.80 ± 0.17 | 7.68 ± 0.84 | 0.15 ± 0.06 |

| Galactoside + Glucoside | 100 ± 2.02 | 960 ± 281 | nd | 0.81 ± 0.15 | 3.62 ± 0.71 | 11.6 ± 2.67 | 0.54 ± 0.28 |

| Malvidins | |||||||

| Arabinoside | 12.6 ± 0.30 | 209 ± 31.5 | nd | 0.32 ± 0.03 | 1.59 ± 0.14 | 6.67 ± 0.57 | 0.16 ± 0.04 |

| Galactoside | 23.9 ± 1.48 | 529 ± 66.8 | nd | 0.78 ± 0.09 | 3.62 ± 0.49 | 12.9 ± 2.21 | 0.15 ± 0.08 |

| Glucoside | 34.5 ± 0.69 | 376 ± 50.0 | nd | 0.45 ± 0.04 | 2.17 ± 0.28 | 7.20 ± 1.27 | 0.22 ± 0.11 |

| Peonidins | |||||||

| Arabinoside | 13.9 ± 0.10 | 56.6 ± 9.61 | nd | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.39 ± 0.03 | 1.66 ± 0.15 | 0.18 ± 0.05 |

| Galactoside | 40.2 ± 0.34 | 227 ± 22.8 | nd | 0.35 ± 0.04 | 1.69 ± 0.14 | 7.18 ± 0.69 | 0.58 ± 0.17 |

| Glucoside | 75.0 ± 1.40 | 249 ± 28.5 | nd | 0.40 ± 0.02 | 1.85 ± 0.15 | 8.06 ± 0.55 | 1.02 ± 0.29 |

| Petunidins | |||||||

| Arabinoside | 28.4 ± 0.30 | 486 ± 71.0 | nd | 0.72 ± 0.07 | 3.47 ± 0.27 | 14.8 ± 1.30 | 0.35 ± 0.12 |

| Galactoside | 59.0 ± 1.42 | 1121 ± 108 | nd | 1.86 ± 0.16 | 8.60 ± 0.57 | 37.3 ± 3.49 | 0.68 ± 0.22 |

| Glucoside | 74.5 ± 0.86 | 598 ± 62.8 | nd | 0.90 ± 0.09 | 4.28 ± 0.32 | 18.7 ± 1.79 | 0.86 ± 0.27 |

| Phenolic Acids | |||||||

| Benzoic Acids | |||||||

| Gallic acid | nd | 18.6 ± 2.99 | nd | 0.029 ± 0.006 | 0.168 ± 2.00 | 0.62 ± 0.11 | nd |

| Protocatechuic acid | 0.57 ± 0.12 | 8.82 ± 1.90 | nd | 0.017 ± 0.003 | 0.070 ± 0.020 | 0.35 ± 0.10 | 0.013 ± 0.004 |

| Cinnamic Acids | |||||||

| Caffeic acid | trace | 47.7 ± 11.7 | nd | 0.064 ± 0.006 | 36.7 ± 0.035 | 1.18 ± 0.06 | 0.007 ± 0.004 |

| Chlorogenic acid | 621 ± 21.7 | 1738 ± 322 | nd | 2.64 ± 0.17 | 13.0 ± 1.30 | 48.9 ± 3.85 | 4.86 ± 0.68 |

| Ferulic acid | 2.01 ± 0.22 | 43.7 ± 7.17 | nd | 0.088 ± 0.005 | 0.41 ± 0.032 | 16.0 ± 0.18 | 0.044 ± 0.008 |

| Feruloylquinic acid | 8.28 ± 0.45 | 33.4 ± 5.33 | nd | 0.074 ± 0.007 | 0.35 ± 0.040 | 14.3 ± 0.13 | 0.143 ± 0.014 |

| Flavan-3-ols | |||||||

| Catechin | 10.7 ± 0.17 | 39.9 ± 12.3 | nd | 0.092 ± 0.020 | 0.37 ± 0.15 | 13.9 ± 0.22 | 0.089 ± 0.030 |

| Epicatechin | 7.78 ± 0.44 | 11.3 ± 4.04 | nd | 0.023 ± 0.008 | 0.10 ± 0.042 | 0.39 ± 0.05 | 0.031 ± 0.013 |

| Epigallocatechin | nd | 20.9 ± 2.79 | nd | 0.048 ± 0.004 | 0.25 ± 0.012 | 0.78 ± 0.07 | nd |

| Flavonols | |||||||

| Myricetin | 1.78 ± 0.15 | 46.3 ± 12.0 | nd | 0.062 ± 0.014 | 0.32 ± 0.046 | 1.09 ± 0.30 | 0.031 ± 0.001 |

| Kaemperol | nd | 10.8 ± 1.12 | nd | 0.028 ± 0.001 | 0.14 ± 0.001 | 0.69 ± 0.01 | nd |

| Galactoside + Glucoside | 96.5 ± 5.26 | 360 ± 52.8 | nd | 0.49 ± 0.064 | 2.37 ± 0.29 | 9.16 ± 0.99 | 1.05 ± 0.40 |

| Quercetin | 1.80 ± 0.18 | 242 ± 48.6 | nd | 0.32 ± 0.050 | 1.60 ± 0.14 | 5.02 ± 1.45 | 0.041 ± 0.009 |

| Galactoside + Glucoside | 309 ± 9.78 | 1165 ± 117 | nd | 19.3 ± 0.12 | 9.25 ± 0.099 | 35.4 ± 2.61 | 4.45 ± 1.18 |

| Rutin | 32.6 ± 0.93 | 74.6 ± 16.3 | nd | 0.12 ± 0.011 | 0.56 ± 0.064 | 2.51 ± 0.21 | 0.431 ± 0.068 |

FD = freeze dried whole blueberries; CE = concentrated blueberry phenolic extract; nd = not detected; trace = compound detected, but below LOQ.

Data are comprised of three analytical replicates and presented as mean ± SD.

Measured via Folin assay.

Identification and quantification of each compound was based on authentic standards, using calibration curves ranging from 0.001-100 μM. When standards were not available, compounds (especially phase II metabolites) were confirmed based on retention times and the presence of multiple ion transitions consistent with each compound.30 A complete list of compounds detected, including corresponding MRMs and standards used for quantification are shown in Table SI–1.

2.5. Statistics

2.5.1. Microbiota Statistics.

Significance for alpha diversity metrics was calculated in QIIME using pairwise Kruskal-Wallis tests. Significance for beta diversity metrics was determined in QIIME using PERMANOVA and permDisp was used to ensure that any significant differences found were due to differences in the actual means of the groups, and not the dispersion of each group. Beta diversity metrics were further analyzed using pairwise distances between day 0 and day 90. Statistical significance for these pairwise analyses was determined using a false discovery rate (FDR)-corrected Mann-Whitney U test. Differential abundances in taxonomy across all samples at day 90 were determined using Analysis of Composition of Microbiomes (ANCOM)31 and Linear discriminant analysis Effect Size (LEfSe).32 In order to determine taxonomic differences due to the whole blueberry food matrix, LEfSe analysis was further conducted on only BB and low samples at day 90. PAST version 4.04 was used to detect correspondence between taxonomy and phenolic data using Canonical Correspondence Analysis (CCA).33 To determine potential relationships between phenolic metabolites and microbial species, linear correlations between phenolic urinary metabolite pools and the relative abundance of species-level taxa were made using Bonferroni-corrected Pearson’s r34 in PAST version 4.04.

2.5.2. Polyphenol Statistics.

Statistics were completed using SAS (SAS Institute, Raleigh, NC). When data were not normal, appropriate transformations were performed before analysis to ensure normality. Outliers were detected and removed using Tukey’s method. Two-way ANOVA was used to determine differences within dose groups (across different time points) and between dose groups (at the same time point). Post hoc analyses were carried out with Tukey’s HSD test, with significance defined as p < 0.05. Guidance in SAS coding was provided by the Statistical Consulting Service at Purdue University.

3. RESULTS

3.1 –. Gut microbiota

In total, 2,158,828 high-quality merged sequences were obtained after processing of MiSeq Illumina sequencing results by DADA2. Per sample, there was a median of 16,491.5 reads (range: 11-92,756). In order to maximize read depth while minimizing excluded samples, a sampling depth of 4,197 reads was chosen for rarefaction. Thus, three samples (BB d0, high d90, and non-gavage d90) were excluded from subsequent analyses.

3.1.1. Taxonomic analysis.

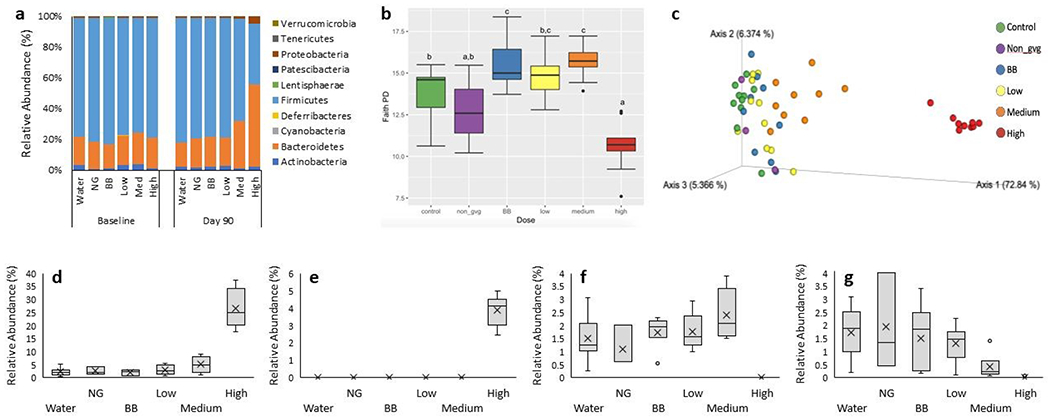

At baseline, microbiome composition was similar amongst groups, with Firmicutes (78%), Bacteroidetes (19%), and Actinobacteria (2.2%) being the most abundant phyla (Figure 1a). After 90d of treatment, blueberry polyphenols induced a significant dose-dependent shift in microbiota community structure (p < 0.01), with the average Firmicutes to Bacteroides ratio (F:B) decreasing from 5.4 (water control group) to 2.2 (medium group) to 0.7 (high group). Additionally, Proteobacteria increased in the high dose group.

Figure 1 –

Characterization of gut microbiota, a) Relative abundances of phyla in gut microbiota of rats at baseline and end of study. b) Faith’s PD illustrating alpha diversity at end of study; lowercase letters indicate significant differences between groups (q < 0.05). c) PCoA plot from weighted Unifrac analysis, illustrating beta diversity for all samples at end of study. d-g) Relative abundances of a few representative differentially abundant taxa identified by LEfSe at end of study. d) B. dorei and e) Lachnoclostridium exhibited dominance in the high dose group, while f) Rickenellaceae RC9 gut group was most abundant in the medium dose group and g) Eubacterium coprostanoligenes group decreased in relative abundance as the phenolic dose increased.

3.1.2. Alpha diversity.

The diversity of gut microbial species within each sample was analyzed by assessing species richness and evenness at the end of the study. In comparison to the water control group, the richness (i.e., number of taxa present) of the BB and medium dose groups increased (q < 0.01), while the high dose group decreased (q < 0.005; Figure 1b). This was true for measurements of richness that incorporated or excluded phylogenetic differences (Faith PD or observed OTUs, respectively). However, when using Pielou’s evenness, which measures the balance of species distribution, none of the treatment groups differed significantly.

3.1.3. Beta diversity.

Differences in gut microbiota structure among samples were analyzed using multiple metrics. Weighted Unifrac, a phylogenetic distance metric which incorporates the relative abundances of each taxon, shows clear separation between rats in the high dose group and other treatment groups (q < 0.05). However, this may be confounded by the significant dispersion effect present (permDisp, p < 0.05), meaning variation may be contributing to the differences observed via weighted Unifrac. To visualize the differences in communities and determine whether treatment group means were truly different, samples from day 90 were plotted using principal coordinate analysis (PCoA, Figure 1c). The PCoA plot illustrates that the gut microbiomes of the high dose rats clearly separate from the other treatment groups along axis 1 that accounts for 72.84% of variation (Weighted Unifrac, q < 0.05). This was confirmed by additional measures of beta diversity, including Bray-Curtis (which compares the presence and abundance of each OTU), Jaccard (which compares numbers of unique OTUs), and unweighted Unifrac (which compares taxonomic differences). In addition to the differences observed for the high dose group, gut microbiomes of the medium dose group were significantly different from all other treatment groups (weighted Unifrac, q < 0.05), and the BB group was significantly different from the water group (weighted Unifrac, q < 0.05). Although dispersion was significantly different for the treatment groups, the PCoA plot shows that the medium, BB, and water control groups form separate clusters despite differences in their dispersion.

3.1.4. Differentially abundant taxa.

Treatment groups were further analyzed for differential taxa through LEfSe (LDA >4) and ANCOM, with several significant differences observed (example Figure 1d–g, all taxa Table SI–2). The high dose group showed the most dramatic differences, with several taxa greatly enriched (e.g., Bacteroides dorei and Lachnoclostridium) and others significantly diminished (e.g., Rickenellaceae RC9 gut group and Eubacterium coprostanoligenes group). In addition, a few taxa were most abundant in the medium dosage group (e.g., Rickenellaceae RC9 gut group and Eubacterium xylanophilum group). Comparison of BB and low dose groups at d90 by LEfSe (LDA>3) revealed one significantly different taxon, an unclassified Alistipes, which had higher relative abundance in the BB group.

3.2 –. Urinary excretion of phenolic metabolites

3.2.1 –. Kinetics.

To assess changes in phenolic metabolism kinetics over the course of the 90d treatment period, 24-hour urine samples were collected at baseline, d7, d15, d30, d60, and d90. A total of 52 phenolic metabolites were analyzed at each time point (Table SI–1). Of these, 36 were quantifiable in at least one treatment group, with two additional compounds being observed in trace amounts (isovanillin in high dose group and homovanillic acid in medium and high dose groups).

Urinary phenolic metabolite profiles varied based on treatment and time point. Total phenolic metabolite excretion exhibited a dose-dependent response throughout the study, with the low, BB, and medium groups reaching maximal metabolite production within 7d of beginning treatment. The high dose group, by contrast, exhibited a steady rise in metabolite production throughout the study (Figure 2a; statistical comparison shown in Table 2). Total phenolic metabolite excretion was similar in the low and BB groups, which was expected, given the matched phenolic content of the doses in those two groups. However, when comparing the medium and high dose groups, they had similar levels of total excretion early in the study, but differences at later time points.

Figure 2 –

Urinary excretion kinetics of total and selected individual phenolic metabolites, illustrating metabolite excretion patterns over 90d (see text for details). a) Total phenolic excretion, b) 3-hydroxyphenyl propionic acid, c) quercetin, d) delphinidin glucuronide, and e) 3-hydroxy-4-methoxyphenylpropionic acid. Data shown as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis for total phenolic excretion is given in Table 2, while graphs of all quantified individual phenolic metabolites and their statistical comparisons are given in the Supporting Information (Figures SI1–SI3).

Table 2 –

Summary of urinary phenolic excretion in rats gavaged purified blueberry phenolics or whole blueberries (μmol excreted).

| Day | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 7 | 15 | 30 | 60 | 90 | |

| Intact Phenolics | ||||||

| Water | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| NG | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| BB | nd | 0.0008 ± 0.0003 c,A | 0.0004 ± 0.0002 d,B | 0.0006 ± 0.0003 c,AB | 0.0006 ± 0.0003 c,AB | 0.0007 ± 0.0003 c,AB |

| Low | nd | 0.0014 ± 0.0007 c,A | 0.0015 ± 0.0007 c,A | 0.0013 ± 0.0010 c,AB | 0.0008 ± 0.0006 c,B | 0.0010 ± 0.0008 c,B |

| Medium | nd | 0.010 ± 0.003 b | 0.012 ± 0.003 b | 0.010 ± 0.005 b | 0.007 ± 0.002 b | 0.008 ± 0.003 b |

| High | nd | 0.032 ± 0.007 a,B | 0.057 ± 0.019 a,A | 0.040 ± 0.017 a,AB | 0.033 ± 0.010 a,AB | 0.044 ± 0.023 a,AB |

| Flavonoid Phase II Metabolites | ||||||

| Water | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| NG | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| BB | nd | 0.0010 ± 0.0004 d,B | 0.0010 ± 0.0006 d,B | 0.0010 ± 0.0003 d,AB | 0.0013 ± 0.0007 c,AB | 0.0018 ± 0.0010 c,A |

| Low | nd | 0.0024 ± 0.0010 c,AB | 0.0018 ± 0.0006 c,AB | 0.0027 ± 0.0012 c,A | 0.0015 ± 0.0007 c,B | 0.0020 ± 0.0008 c,AB |

| Medium | nd | 0.010 ± 0.005 b | 0.011 ± 0.004 b | 0.015 ± 0.007 b | 0.011 ± 0.004 b | 0.012 ± 0.002 b |

| High | nd | 0.067 ± 0.027 a,B | 0.084 ± 0.027 a,AB | 0.129 ± 0.044 a,A | 0.095 ± 0.035 a,AB | 0.109 ± 0.028 a,AB |

| Phenolic Acids | ||||||

| Water | 0.007 ± 0.004 C | 0.037 ± 0.037 d | 0.012 ± 0.007 d,BC | 0.012 ± 0.005 d,BC | 0.009 ± 0.002 d,BC | 0.015 ± 0.006 d,B |

| NG | 0.010 ± 0.006 | 0.022 ± 0.019 d | 0.012 ± 0.003 d | 0.010 ± 0.005 d | 0.012 ± 0.003 d | 0.013 ± 0.004 d |

| BB | 0.012 ± 0.010 B | 0.661 ± 0.238 c,A | 0.499 ± 0.101 c,A | 0.402 ± 0.060 c,A | 0.426 ± 0.211 c,A | 0.481 ± 0.315 c,A |

| Low | 0.008 ± 0.004 B | 0.566 ± 0.141 c,A | 0.398 ± 0.121 c,A | 0.432 ± 0.146 c,A | 0.328 ± 0.101 c,A | 0.417 ± 0.129 c,A |

| Medium | 0.015 ± 0.008 B | 2.091 ± 0.928 b,A | 1.825 ± 0.688 b,A | 1.918 ± 0.809 b,A | 1.570 ± 0.324 b,A | 2.559 ± 0.827 b,A |

| High | 0.009 ± 0.006 B | 7.777 ± 4.246 a,A | 6.901 ± 2.274 a,A | 7.321 ± 2.259 a,A | 7.090 ± 2.949 a,A | 8.493 ± 3.230 a,A |

| Phenolic Acid Phase II Metabolites | ||||||

| Water | 2.38 ± 1.02 B | 3.73 ± 1.26 de,A | 2.64 ± 0.78 d | 3.41 ± 0.96 c,AB | 2.50 ± 0.46 d,AB | 3.29 ± 0.41 d,AB |

| NG | 3.52 ± 1.60 | 2.88 ± 1.02 e | 4.54 ± 0.76 cd | 2.72 ± 0.61 c | 2.56 ± 0.90 d | 2.59 ± 0.46 d |

| BB | 3.42 ± 1.35 C | 5.81 ± 1.22 cd,A | 6.87 ± 1.80 bc,BC | 4.46 ± 1.48 c,AB | 6.13 ± 0.52 c,AB | 7.28 ± 2.69 c,AB |

| Low | 2.87 ± 0.92 C | 12.2 ± 3.74 bc,A | 6.69 ± 1.79 bc,B | 10.2 ± 3.17 b,AB | 6.21 ± 2.07 c,B | 9.45 ± 3.84 c,AB |

| Medium | 3.35 ± 1.04 B | 39.5 ± 13.3 a,A | 26.9 ± 11.5 a,A | 32.6 ± 13.2 a,A | 26.5 ± 10.2 b,A | 36.5 ± 15.6 b,A |

| High | 3.38 ± 0.78 D | 34.0 ± 6.87 a,C | 44.5 ± 26.0 a,C | 47.7 ± 20.0 a,BC | 69.1 ± 26.4 a,AB | 77.1 ± 32.1 a,A |

| Hippuric Acids | ||||||

| Water | 0.97 ± 0.45 | 1.35 ± 0.50 b | 1.10 ± 0.30 c | 1.33 ± 0.50 c | 0.92 ± 0.29 c | 1.19 ± 0.21 c |

| NG | 1.33 ± 0.61 | 1.08 ± 0.44 b | 1.43 ± 0.17 bc | 0.93 ± 0.36 c | 1.04 ± 0.31 bc | 0.97 ± 0.13 c |

| BB | 1.31 ± 0.49 B | 3.38 ± 0.88 a,A | 4.33 ± 1.45 a,A | 3.11 ± 0.73 ab,A | 3.75 ± 0.81 a,A | 3.59 ± 1.27 ab,A |

| Low | 1.25 ± 0.42 C | 2.43 ± 0.89 a,A | 2.04 ± 0.53 b,AB | 2.87 ± 0.81 b,A | 1.65 ± 0.49 b,BC | 2.45 ± 1.06 b,A |

| Medium | 1.52 ± 0.50 B | 3.96 ± 1.41 a,A | 4.05 ± 1.57 a,A | 4.23 ± 1.92 a,bA | 4.01 ± 1.21 a,A | 4.17 ± 0.62 a,A |

| High | 1.36 ± 0.38 C | 3.01 ± 0.63 a,B | 6.28 ± 3.74 a,A | 4.66 ± 1.07 a,A | 6.00 ± 1.49 a,A | 5.45 ± 1.42 a,A |

| Total Excretion | ||||||

| Water | 3.34 ± 1.45 | 5.11 ± 1.67 c | 3.75 ± 1.04 e | 4.76 ± 1.39 d | 3.42 ± 0.72 d | 4.50 ± 0.53 d |

| NG | 4.86 ± 2.08 | 3.98 ± 1.41 c | 5.98 ± 0.62 de | 3.67 ± 0.96 d | 3.62 ± 1.16 d | 3.58 ± 0.46 d |

| BB | 4.75 ± 1.76 B | 9.48 ± 1.91 b,A | 11.7 ± 2.34 c,A | 7.98 ± 2.17 c,A | 10.4 ± 0.97 c,A | 11.4 ± 3.88 c,A |

| Low | 4.12 ± 1.29 C | 15.2 ± 4.32 b,A | 9.13 ± 2.23 cd,B | 13.5 ± 3.71 b,A | 8.19 ± 2.46 c,B | 12.3 ± 4.87 c,AB |

| Medium | 4.89 ± 1.43 B | 45.5 ± 14.3 a,A | 32.8 ± 13.2 b,A | 38.8 ± 14.8 a,A | 32.1 ± 11.5 b,A | 42.7 ± 16.8 b,A |

| High | 4.74 ± 1.11 C | 44.9 ± 7.91 a,B | 57.2 ± 29.2 a,B | 59.3 ± 20.2 a,AB | 81.7 ± 27.6 a,A | 91.2 ± 34.6 a,A |

Data presented as mean ± SD. Lower case letters indicate differences between doses at the same time point (i.e., down a column), while upper case letters indicate differences between time points and within dose (i.e., across a row). Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD (p<0.05) used for all comparisons.

NG = non-gavaged group; nd = not detected.

Urinary excretion kinetics of individual phenolic metabolites varied, though several common excretion patterns were observed (Figure 2b–e). Half of the quantified metabolites reached maximal levels of excretion within 7-15 days and then plateaued, exhibiting consistent excretion for the remainder of the study (e.g., 3-hydroxy phenylpropionic acid, Figure 2b). In contrast to this early rise and plateau, many other metabolites showed fluctuations in their production throughout the study. This was observed in opposite ways throughout the study: metabolite production either increased throughout the 90d treatment (e.g., quercetin, Figure 2c) or showed maximal levels of excretion at early time points before decreasing to lower levels at later time points (e.g., delphinidin glucuronide, Figure 2d). Finally, there were several metabolites that exhibited similar levels of urinary excretion in the medium and high dose groups, which indicates that the production and/or absorption of these compounds is perhaps saturable at higher doses (e.g., 3-hydroxy-4-methoxy phenylpropionic acid, Figure 2e). Other metabolites quantified in this study exhibited excretion kinetics similar to the ones shown in Figure 2b–e. Table 3 lists all quantifiable metabolites in the present study, categorized by their excretion kinetics. Graphical illustrations, quantification, and statistical comparisons for the kinetics of all urinary phenolic metabolites quantified in this study are shown in the Supporting Information (Figures SI1–SI3).

Table 3 –

Qualitative kinetics of metabolite excretion for all quantified metabolites, corresponding to patterns of metabolite kinetics depicted in Figure 2b–e.

| Metabolites with excretion patterns similar to: | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fig. 2b | Fig. 2c | Fig. 2d | Fig. 2e |

| 3-OH-PPA | Caffeic acid | Del-3-gal | 3-OH-4-OMe-PPA |

| 4-OMe-quercetin | Caffeic acid sulfs | Del-3-glu | 3-OH-hippuric acid |

| Caffeic acid gcnd | Ferulic acid | Del gcnd | Dihydrocaffeic acid sulf |

| Chlorogenic acid | Myricetin | Malv-3-gal | Hippuric acid |

| Cyn-3-gal | Peon-3-gal | Malv-3-glu | |

| Cyn-3-glu | Pet gcnd | Myricetin gcnd | |

| Ferulic acid gcnds | Quercetin | Pet-3-gal | |

| Isoferulic acid | Pet-3-glu | ||

| Isoferulic acid gcnd | |||

| Isoferulic acid sulfs | |||

| Peon-3-glu | |||

| Quercetin gcnds | |||

| Syringic acid | |||

| Vanillic acid | |||

OH = hydoxy; PPA = phenyl propionic acid; OMe = methoxy; gcnd(s) = glucuronide(s); Cyn = cyanidin; gal = galactoside; glu = glucoside; sulf(s) = sulfate(s); Peon = peonidin; Pet = petunidin; Del = delphinidin; Malv = malvidin.

3.2.2 –. Metabolic flux.

Many of the metabolites measured in the present study can be derived from different dietary inputs, especially from diets rich in polyphenols.35 To isolate the effects of blueberry polyphenols, all rats were maintained on a polyphenol-free diet for 30d prior to and then throughout the study, meaning that any changes in metabolites measured were due primarily to blueberry phenolic treatment. Quantifiable amounts of phenolic and hippuric acids were observed in all groups at baseline. However, none of the larger phenolics native to blueberries, including flavonoids, were observed prior to introduction of blueberry polyphenols suggesting these background metabolites are derived from other sources in the rodent diet. Additionally, the large changes observed in phenolic and hippuric acid metabolites throughout the study are direct evidence that administration of blueberry polyphenols significantly altered metabolic flux.

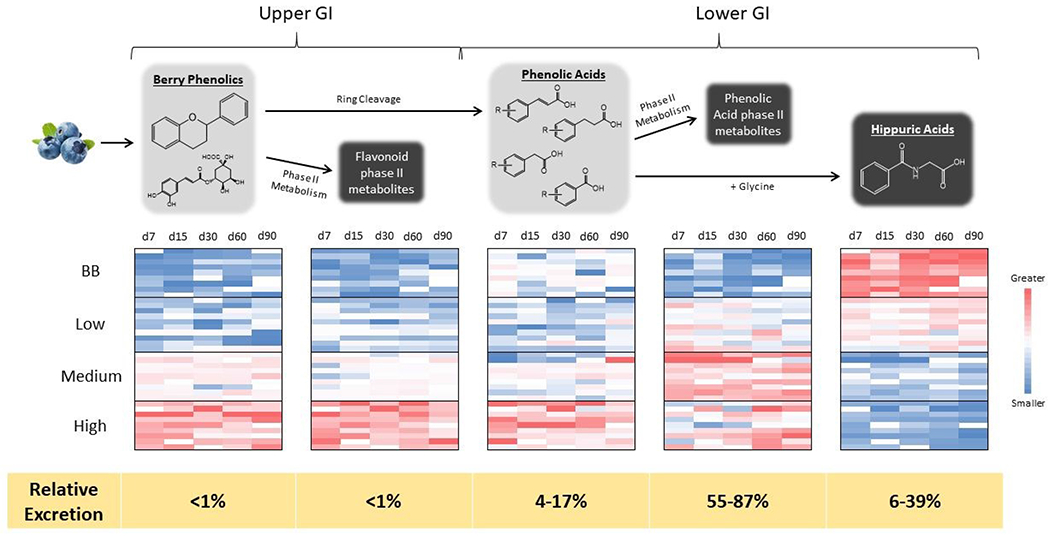

Shifts in the relative and absolute amounts of blueberry polyphenol metabolites are shown in Figure 3 and Table 2, which highlight the similarities and differences between treatment groups. In general, urinary metabolite production of structurally related metabolites was consistent within treatment groups over 90d.

Figure 3 –

Metabolic flux of phenolic metabolites. The top half of the figure illustrates a simplified schema of phenolic metabolism throughout the GI tract. The five boxes represent the five different metabolite pools produced (light grey boxes indicate metabolites produced within the GI tract, while dark grey boxes indicate host xenobiotic metabolites). The heat maps compare the relative differences between treatments for each metabolite pool. These plots were generated from the percent contribution of each metabolite pool to the total phenolic excretion, enabling meaningful comparisons between treatments. Finally, as illustrated by the yellow bar at the bottom of the figure, regardless of treatment, metabolites derived from lower intestinal metabolism, and specifically host xenobiotic metabolism of gut microbial metabolites, accounted for a large majority of the metabolites observed.

There were several dose-dependent differences in metabolic flux observed between treatment groups. As shown in the heat maps in Figure 3, increasing doses of blueberry phenolics resulted in the formation of higher relative levels of metabolites from the upper GI (both intact and host xenobiotic metabolites) as well as more intact phenolic acids. Conversely, metabolites formed later in the metabolic chain (i.e., phenolic acid phase II metabolites and hippuric acids) were found in larger relative amounts in the lower dose groups.

When comparing the dose-matched BB and low groups, there were distinct differences in their metabolite profiles, indicating a significant food matrix effect (see heat maps in Figure 3 and statistical comparisons in Table 2). This effect was most pronounced when comparing lower GI metabolites (and subsequent host xenobiotic metabolites), as the low-dose group produced larger amounts of phenolic acid phase II metabolites but smaller amounts of hippuric acids than the BB-dose group. Interestingly, the production of hippuric acids in the BB group was not significantly different from the medium or high dose groups (Table 2).

The relative contribution of the different metabolite pools to total phenolic metabolism varied among treatments (see yellow bar at bottom of Figure 3). Regardless of treatment, there was a clear dominance of lower GI-derived metabolites, and, specifically, of host xenobiotic metabolites of gut microbially-generated metabolites.

3.3 –. Tissue distribution of phenolic metabolites.

To assess if differences in urinary phenolic excretion were due to tissue storage and accumulation, we analyzed phenolic metabolites in key metabolic tissues at sacrifice, 24h after the last oral gavage was administered (Table 4). The largest number of metabolites were detected in GI tissues, which is unsurprising given both the extensive interaction between phenolics and the GI tract as well as the presence of darkened digesta in the colons of rats dosed with phenolics at sacrifice, an indication that the final phenolic dose had not been fully cleared.

Table 4 –

Tissue distribution of polyphenols & their metabolites in rats gavaged purified blueberry phenolics or whole blueberries.

| Tissue Polyphenols (ng polyphenol / g tissue) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | NG | Low | BB | Medium | High | |

| GI Tissues (n) | 9 | 4 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 9 |

| Small Intestine | ||||||

| Delphinidin-3-gal | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | trace (4) |

| Malvidin-3-gal | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | trace (5) |

| Petunidin-3-gal | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | trace (7) |

| Syringic Acid | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | trace (2) |

| 3-OMe-PAA | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | trace (4) |

| 3-OH-PPA | nd | nd | trace (3) | nd | trace (2) | 20 - 79 (6) |

| DHCA sulf | nd | nd | nd | trace (3) | trace (3) | trace (5) |

| Ferulic acid gcnd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.5 - 8.3 (5) | 1.7 - 8.9 (3) |

| Ferulic acid sulf | 3.9 - 58 (4) | 3.6 - 7.0 (2) | 3.4 - 55 (4) | 3.3 - 256 (7) | 5.8 - 135 (7) | 1.9 - 173 (9) |

| Hippuric acid | 10 - 796 (7) | 20 - 42 (4) | 22 - 430 (9) | 10 - 1396 (9) | 43 - 678 (8) | 37 - 1773 (9) |

| 3-OH-hippuric | nd | nd | nd | trace (3) | trace (6) | trace (3) |

| Quercetin gcnd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.23 - 1.58 (6) |

| Colon | ||||||

| Delphinidin-3-gal | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | trace (5) |

| Malvidin-3-gal | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | trace (7) |

| Petunidin-3-gal | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | trace (6) |

| Syringic Acid | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | trace (3) |

| 3-OMe-PAA | nd | nd | trace (2) | trace (2) | trace (5) | trace (4) |

| 3-OH-PPA | 17 - 37 (3) | nd | 49 - 52 (3) | 24 - 459 (2) | 104 - 4549 (3) | 27 - 5897 (5) |

| Ferulic acid gcnd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 2.5 - 29 (5) | trace (2) |

| Ferulic acid sulf | nd | nd | nd | nd | trace (2) | trace (2) |

| Hippuric acid | 64 - 131 (2) | nd | 16 - 60 (4) | 26 - 64 (2) | 95 - 874 (3) | 10 - 112 (6) |

| Peripheral Tissues (n) | 10 | 4 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 10 |

| Brain | ||||||

| Isovanillin | nd | nd | nd | trace (3) | nd | trace (2) |

| 3-OH-PPA | nd | nd | nd | nd | trace (1) | 12 - 67 (4) |

| DHCA sulf | 13 - 137 (10) | 37 - 129 (4) | 6.9 - 106 (10) | 27 - 97 (9) | 14 - 128 (9) | 24 - 102 (10) |

| Kidney | ||||||

| 3-OH-PPA | trace (2) | nd | nd | trace (1) | 20 - 309 (3) | 48 - 2593 (5) |

| Caffeic acid sulf | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | trace (4) |

| Ferulic acid gcnd | nd | nd | nd | nd | trace (5) | trace (4) |

| Hippuric acid | 18 - 311 (10)b | 30 - 93 (4)b | 29 - 345 (10)b | 11 - 496 (9)b | 116 - 716 (9)ab | 80 - 1661 (10)a |

| 3-OH-hippuric | nd | nd | nd | nd | trace (6) | trace (6) |

| Quercetin gcnd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.05 - 0.90 (5) |

| Liver | ||||||

| Isovanillin | trace (2) | nd | trace (2) | trace (1) | trace (2) | nd |

| 3-OH-PPA | trace (2) | nd | trace (2) | trace (1) | 0.8 - 56 (5) | 0.4 - 490 (5) |

| Caffeic acid sulf | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | trace (4) |

| Ferulic acid gcnd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | trace (2) |

| Hippuric acid | 4.5 - 17 (6)b | 9.4 (1)ab | 3.9 - 155 (9)b | 4.0 - 22 (7)ab | 8.5 - 89 (7)ab | 10 - 181 (10)a |

| Quercetin gcnd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | trace (2) |

Data shown as range of concentrations observed, with the total number of samples the metabolite was observed in indicated in parentheses. Statistically significant differences between groups denoted by lower case letters using Tukey’s HSD test (p < 0.05). DHCA = dihydrocaffeic acid; gal = galactoside; gcnd = glucuronide; nd = not detected; NG = non-gavaged group; PAA = phenylacetic acid; PPA = phenylpropionic acid; sulf = sulfate; trace = metabolite observed, but below the LOQ.

In the small intestine, a total of 12 metabolites were observed, with 5 being quantifiable. Of the quantifiable metabolites, only hippuric acid and ferulic acid sulfate were observed in all groups. No significant differences in tissue concentration were observed between treatment groups, though ferulic acid sulfate was found in a higher percentage of rats as dose increased, indicating a dose-response relationship. Other detected metabolites also showed dose-dependent relationships, as they were primarily observed in higher dose groups.

In the colon, a total of 9 metabolites were observed in at least one treatment group, with 3 being quantifiable. Similar to the small intestine, a dose-dependent response was observed, with metabolites detected in a higher percentage of animals as the phenolic dose increased. Despite this observed trend, there were no statistically significant differences in quantifiable metabolites.

In the brain, three metabolites were observed, with only dihydrocaffeic acid sulfate observed in all animals. In both the liver and kidney, a total of 6 metabolites were observed, with 5 of the 6 (3-hydroxy phenylpropionic acid, caffeic acid sulfate, ferulic acid glucuronide, hippuric acid, and quercetin glucuronide) found in both tissues. Similar to GI tissues, hepatic and renal metabolites exhibited a dose-dependent relationship, with hippuric acid reaching statistical significance.

3.4. Correlations between phenolic metabolism and gut microbiota.

Based on CCA, all metabolites were correlated with the microbiomes of rats in the high dose group (Figure SI–4). Linear correlations were used to further determine the relationship between the relative abundances of specific microbial taxa and urinary phenolic metabolites (Table 5). Many of the taxa that were identified as differentially abundant by LEfSe and ANCOM positively correlated with phenolic metabolites. Three taxa were significantly correlated with all metabolite groups: an uncultured Coriobacteriales, an uncultured Bacteroides and Flavonifracter. Thirteeen taxa positively correlated with all metabolite groups except hippuric acids, including six that were differentially abundant in the high dose group: Bactoroides dorei, Barnesiella, Lachnoclostridium, Rhodospirillales, Ruminococcus torques, and Ruminococcaceae UBA1819. Only one taxon was negatively correlated with the excreted metabolite groups: Christensenellaceae R-7 group, bacterium YE57. This taxon was present in water and low dose groups, but reduced in the rats in the high dose group.

Table 5 –

Linear correlation of urinary phenolic metabolite pools to the relative abundance of microbial taxa in all rats at d90.

| Taxa | Intact phenolics | Flavonoid phase 2 metabolites | Phenolic acids | Phenolic acid phase 2 metabolites | Hippuric acids | Total excretion | Most Abundant In |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavonifractor | 0.93* | 0.89* | 0.91* | 0.85* | 0.67* | 0.86* | High |

| Bacteroides | 0.78* | 0.80* | 0.87* | 0.90* | 0.72* | 0.90* | High |

| Coriobacteriales incertae sedis, uncultured | 0.72* | 0.80* | 0.73* | 0.71* | 0.69* | 0.73* | High |

| Bacteroides dorei | 0.79* | 0.92* | 0.78* | 0.73* | 0.52 | 0.74* | High |

| Barnesiella | 0.93* | 0.96* | 0.94* | 0.82* | 0.65 | 0.84* | High |

| Lachnoclostridium | 0.83* | 0.95* | 0.84* | 0.84* | 0.63 | 0.84* | High |

| Rhodospirillales, uncultured, ambiguous taxa | 0.72* | 0.69* | 0.79* | 0.80* | 0.63 | 0.81* | High |

| Ruminococcus torques group | 0.81* | 0.66* | 0.86* | 0.68* | 0.56 | 0.71* | High |

| Ruminococcaceae UBA1819 | 0.82* | 0.95* | 0.89* | 0.85* | 0.65 | 0.86* | High |

| Alistipes, unidentified | 0.93* | 0.86* | 0.90* | 0.82* | 0.65 | 0.84* | |

| Alistipes | 0.79* | 0.93* | 0.81* | 0.70* | 0.57 | 0.72* | |

| Desulfovibrionaceae, uncultured, ambiguous taxa | 0.85* | 0.94* | 0.85* | 0.84* | 0.63 | 0.84* | |

| Desulfovibrio brachyspira sp. NSH 25 | 0.67* | 0.72* | 0.74* | 0.72* | 0.61 | 0.74* | |

| Fournierella, uncultured organism | 0.89* | 0.83* | 0.80* | 0.66* | 0.54 | 0.68* | |

| Lachnospiraceae, uncultured | 0.69* | 0.65* | 0.72* | 0.73* | 0.62 | 0.74* | |

| Uncultured Parabacteroides sp. | 0.86* | 0.89* | 0.93* | 0.79* | 0.64 | 0.81* | |

| Adlercreutzia, uncultured bacterium | 0.78* | 0.84* | 0.74* | 0.64 | 0.58 | 0.66* | |

| Unclassified Coriobacteriales | 0.67* | 0.68* | 0.77* | 0.63 | 0.63 | 0.66* | |

| Ruminococcus-2 | 0.65* | 0.70* | 0.67* | 0.60 | 0.51 | 0.62 | High |

| Akkermansia | 0.80* | 0.84* | 0.81* | 0.59 | 0.45 | 0.62 | |

| Blautia | 0.69* | 0.71* | 0.67* | 0.60 | 0.47 | 0.62 | |

| Enterorhabdus, uncultured bacterium | 0.85* | 0.84* | 0.73* | 0.61 | 0.49 | 0.63 | |

| Eubacterium nodatum group | 0.80* | 0.58 | 0.61 | 0.42 | 0.39 | 0.45 | |

| Sellimonas, uncultured bacterium | 0.78* | 0.42 | 0.66* | 0.51 | 0.43 | 0.53 | |

| Terrisporobacter, ambiguous taxa | 0.67* | 0.38 | 0.52 | 0.36 | 0.30 | 0.38 | |

| Uncultured Clostridiales vadinBB60 group, gut metagenome | 0.54 | 0.79* | 0.65* | 0.77* | 0.55 | 0.76* | |

| Parabacteroides merdae | 0.56 | 0.62 | 0.57 | 0.68* | 0.49 | 0.67* | |

| Marvinbryantia | 0.59 | 0.85* | 0.65 | 0.58 | 0.43 | 0.59 | High |

| Christensenellaceae, uncultured organism | 0.63 | 0.85* | 0.71* | 0.59 | 0.52 | 0.61 | |

| Parabacteroides | 0.51 | 0.74* | 0.67* | 0.61 | 0.48 | 0.62 | |

| Enterorhabdus, mouse gut metagenome | 0.59 | 0.86* | 0.65 | 0.54 | 0.37 | 0.56 | |

| Ruminococcaceae UCG-008, uncultured bacterium | 0.42 | 0.65* | 0.55 | 0.48 | 0.37 | 0.49 | |

| Parasutterella, ambiguous taxa | 0.65 | 0.75* | 0.62 | 0.54 | 0.31 | 0.55 | |

| Lachnospiraceae UCG-008 | 0.60 | 0.78* | 0.63 | 0.44 | 0.34 | 0.46 | |

| Phocea, uncultured bacterium | 0.47 | 0.57 | 0.67* | 0.61 | 0.50 | 0.62 | |

| Rhodospirillales, uncultured | 0.53 | 0.55 | 0.65* | 0.63 | 0.51 | 0.64 | |

| Christensenellaceae R7 group, bacterium-YE57 | −0.67* | −0.70* | −0.70* | −0.68* | −0.47 | −0.68* |

Data presented as Pearson’s r. Only taxa with significant correlations to at least one metabolite are shown. Significant correlations (p<0.05) are marked with an *. If taxa were identified as differentially abundant, the treatment group in which they were most abundant is listed.

4. DISCUSSION

There were clear dose-dependent effects of blueberry polyphenols on both the gut microbiota and phenolic metabolism over 90d in a rat model of postmenopausal estrogen deficiency. The diversity and structure of the gut microbiota were significantly altered by the dose of blueberry polyphenols, and it is likely that the microbial communities shifted in response to increased phenolic loads toward more efficient metabolism of ingested phenolics. This is supported by the increased levels of phenolic metabolites observed in the high dose group, especially at later time points in the study. As the composition of the gut microbiota shifted to adapt to higher phenolic loads, the phenolic metabolites observed in the urine and tissues also shifted (Figure 3 and Table 4), which may indicate that certain microbes are more efficient at producing certain metabolites or that the usual metabolic processes are overwhelmed and saturated at higher doses. These results are consistent with what we observed in our acute, single dose study.19 The change in metabolic flux observed in both our previous single-dose study and the present repeat dose 90d study may be due to several factors, though we posit it is the result of several factors: shifting gut microbial populations and saturation of metabolic pathways. As shown in Figure 3, the relative abundance of upper GI metabolites were favored in higher dose groups, whereas the presence of lower GI metabolites were favored in lower dose groups. This may be indicative of the increasing dose saturating metabolic pathways in the lower gut, causing an accumulation of earlier phenolic metabolites. As these earlier metabolites may be present for longer periods of time, they may be absorbed at higher relative levels with increasing dose, creating the relative excretion patterns shown.

Ingesting blueberry phenolics results in a complex phenolic metabolite pool consisting of both host and microbial metabolites. In a previous study feeding blueberries to rats and measuring phenolic metabolism via 24h urine collections, several metabolites reached steady-state production in 4 weeks while others showed continual increases in production up to 8 weeks.36 In a human study, many of the phenolic metabolites measured were present at baseline, but the ingestion of blueberry phenolics significantly altered the total amounts of phenolic metabolites in these metabolite pools, indicating significant impacts on metabolic flux after blueberry consumption.35 Additionally, similar to our study, the authors noted high levels of microbially-derived phenolic metabolites, including phenolic and hippuric acids as well as their phase II metabolites.35

Based on the continual increase of phenolic metabolites observed in the high dose over the course of 90d, we hypothesized that high doses of blueberry phenolics may cause metabolites to accumulate in tissues over time. To investigate this hypothesis, we analyzed several tissues. Most metabolites were detected in GI tissues, which is consistent with other studies of polyphenols.37–39 In the peripheral tissues, with the exception of hippuric acid, we saw little evidence of phenolic metabolites accumulating, which is consistent with another study of blueberries in rats, though we used higher levels of blueberry phenolics in the present study.36

The presence of hippuric acid in liver and kidney was not surprising, as it can arise from many different dietary precursors and is formed in the liver before being filtered in the kidney and excreted in the urine.40 However, given the lack of quantifiable phenolic metabolites in other tissues, the significant dose-response relationship between treatment groups indicates that even 24h after receiving the final dose, animals are still clearing phenolic metabolites from that dose. As many studies report the rapid clearance of most phenolic metabolites from systemic circulation,41 the fact that hippuric acid is still observed in the liver 24h after receiving the final dose lends further credence to the hypothesis that phenolic metabolites may persist in circulation longer than originally thought.41–43

Blueberries contain significant amounts of polyphenols, fiber, and sugars, all of which can modulate or be utilized by the gut microbiota.18, 44 To better understand the impact of these food matrix factors on phenolic metabolism and the gut microbiota, we used dose-matched treatment groups containing lyophilized whole blueberries or purified phenolics. When comparing these two treatment groups to each other, several differences were observed. Although there were no statistically significant differences in overall gut microbial diversity between the low and BB groups, one taxon (Alistipes) was differentially abundant, with higher relative abundance in the BB group. Alistipes is a diverse genus with thus far conflicting evidence for function in the gut microbiome and involvement in disease progession 45 Further characterization and identification of species within the Alistipes genus is needed to better understand its role in this particular case. Additionally, there were differences in metabolic flux between these groups, with the low dose group producing higher levels of phenolic acid phase II metabolites, while the BB group favored phenolic and hippuric acid metabolites. Taken together, our results indicate that the food matrix differentially influences the gut microbial metabolism of whole foods versus dietary supplements. As observed previously, the food matrix impacts the health benefits derived from phenolics.46

Polyphenols are increasingly being recognized as dietary hormetins, with beneficial effects at low doses but adverse effects at higher doses.47, 48 Hormesis was originally defined in a toxicological context as a dose-response relationship that provided stimulation at low doses, but was inhibitory at high doses.49 This definition has been expanded to encapsulate the idea that small quantities/doses have the opposite effect of large quantities/doses.50 However, hormetic effect sizes are usually small, making them difficult to detect in biological systems.49

Although we did not observe any overt toxicity from blueberry polyphenols,20 we hypothesized that increasing doses of blueberries would induce an hormetic response in phenolic metabolism and gut microbial diversity. Our results support this hypothesis, as blueberry polyphenols had differential effects at different doses: phenolic metabolism shifted in a dose-dependent manner, while gut microbial diversity was increased at moderate doses but decreased at higher doses. Increases in gut microbial diversity have been linked to a healthier gut microbiome and, consequently, better overall health outcomes for the host.51 Conversely, decreases in gut microbial diversity are linked to adverse health outcomes in the host, including irritable bowel syndrome, Clostridium difficile infection, colorectal cancer, and allergies.52 Our results indicate that, at moderate doses, blueberry polyphenols act in a prebiotic-like fashion by enriching the gut microbiota, while at higher doses, they select strongly for certain taxa.

We identified several microbial species which were significantly correlated with certain polyphenol metabolites, which may be indicative of metabolic relationships. While many of these correlations are likely reflective of the fact that certain phenolic metabolites and taxa were co-correlated with the high dose, they may also reflect a metabolic relationship, where these taxa either produce or compete well in the presence of these metabolites. In particular, the taxa that correlate with intact phenols probably compete well in their presence, and the taxa that correlate with other metabolites may be responsible for the metabolic pathways leading to their production. Further studies on the relationship between specific microbial species and phenolic metabolites that showed dose-dependent differences are needed.

Previous studies have demonstrated that polyphenols may beneficially impact bone health in clinical and preclinical models of postmenopausal bone loss.53–56 Although not the focus of the current article, we previously reported that there were no changes in bone mineral density (BMD) among the treatment groups in the present study.20 BMD for femur, tibia, and vertebra in these animals matches expected values for OVX Sprague-Dawley rats of similar age and time post-surgery.57 Additionally, further testing of bone mechanical properties via three-point-bending of femurs from rats in used in the present study showed no differences in bone toughness, stiffness, or resistance to fracture.58 Thus, we did not see significant a significant effect of blueberry polyphenols administered in the current study and bone health.

The present study has numerous strengths. The principle strength of this study is that we analyzed dose- and food matrix-dependent changes in both phenolic metabolism and the gut microbiota. As most studies focus on only one of these aspects, our data allows us to begin drawing dose- and food matrix-dependent connections between orally-ingested polyphenols, changes in gut microbial populations and diversity, and absorbed metabolites. These connections will be key to furthering our understanding of how phenolic metabolites ultimately influence health outcomes. Additionally, we used far higher doses of polyphenols to assess these endpoints than those employed in other clinical and preclinical studies. Using purified blueberry polyphenols is directly relevant to dietary supplement usage and consumption. Because we compared both the dose- and food matrix-dependent effects of blueberry polyphenols in the current study, our data allow for a direct comparison of both phenolic metabolism and gut microbial populations after intake of whole blueberries or purified phenolics in dietary supplements. The clear shifts in both the relative and absolute amounts of metabolites produced as well as changes in gut microbial structure highlight the differences due to dose and food matrix. In future studies, this is a key point for investigators to keep in mind, as the dosing methodology has direct consequences for metabolism and may also influence observed health effects.

There are several limitations in our study as well. First, we used an OVX rat model, which may or may not be generalizable to other rat models (healthy or diseased). Second, we administered gavage doses shortly after “lights on” each day, which corresponds to the sleep period for the rat. However, given the length of the study and the consistent time of dosing across treatment groups, this should not appreciably confound results. Finally, we collected and analyzed urinary phenolic metabolites (but not serum metabolites) to reflect the cumulative pool of excreted phenolic metabolites, which may have caused us to miss some systemically delivered metabolites.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Blueberry polyphenols induce dose- and food matrix-dependent shifts in the production of phenolic metabolites and the composition of the gut microbiota. Because nearly all phenolic metabolites measured in this study are derived from the gut microbial metabolism of polyphenols (and subsequent host xenobiotic phase II metabolism), our results support the hypothesis that increased doses of blueberry polyphenols result in a shift in the gut microbiota to compositions that more efficiently metabolize blueberry polyphenols. Additionally, several taxa were highly abundant in the medium dose group but were undetectable in the high dose group, which may explain the metabolic saturation effects observed in the high dose group. Taken together, our results indicate that high doses of purified blueberry polyphenols, as may be found in dietary supplements, induce changes in the composition of the gut microbiota and the production of phenolic metabolites as compared to lower doses of whole blueberries. Because the composition of the gut microbiota and the circulating bioactive phenolic metabolites influence health outcomes, our results indicate that consuming blueberry dietary supplements versus whole fruits may have differential effects on health.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was funded by the National Institutes of Health (R01AT008754). The authors acknowledge the assistance of Pamela Lachcik, Dr. Hawi Debelo, Josie Austin, Kaylee Brunsting, Lindsey Bullerman, Abby Emigh, Samuel Loebig, Samantha Meima, Emilee Pfeifer, Erin Roy, Samuel Westendorf, and Xinyue Xie in the completion of this project.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

There are no conflicts to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hussain T, Tan B, Yin YL, Blachier F, Tossou MCB and Rahu N, Oxidative stress and inflammation: what polyphenols can do for us?, Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev, 2016, 2016, 7432797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Navaei N, Pourafshar S, Akhavan NS, Litwin NS, Foley EM, George KS, et al. , Influence of daily fresh pear consumption on biomarkers of cardiometabolic health in middle-aged/older adults with metabolic syndrome: a randomized controlled trial, Food Funct., 2019, 10, 1062–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spencer JPE, The impact of fruit flavonoids on memory and cognition, Brit. J. Nutr, 2010, 104, S40–S47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Del Rio D, Rodriguez-Mateos A, Spencer JPE, Tognolini M, Borges G and Crozier A, Dietary (poly)phenolics in human health: structures, bioavailability, and evidence of protective effects against chronic diseases, Antioxid. Redox Signal, 2013, 18, 1818–1892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boeing H, Bechthold A, Bub A, Ellinger S, Haller D, Kroke A, et al. Critical review: vegetables and fruit in the prevention of chronic diseases, Eur. J. Nutr, 2012, 51, 637–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson SA, Figueroa A, Navaei N, Wong A, Kalfon R, Ormsbee LT, et al. Daily blueberry consumption improves blood pressure and arterial stiffness in postmenopausal women with pre- and stage 1-hypertension: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial, J. Acad. Nutr. Diet, 2015, 115, 369–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmet I, Spangler E, Shukitt-Hale B, Juhaszova M, Sollott SJ, Joseph JA, et al. Blueberry-enriched diet protects rat heart from ischemic damage, Plos One, 2009, 4, e5954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sweeney MI, Kalt W, MacKinnon SL, Ashby J and Gottschall-Pass KT, Feeding rats diets enriched in lowbush blueberries for six weeks decreases ischemia-induced brain damage, Nutr. Neurosci, 2002, 5, 427–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kay CD, Pereira-Caro G, Ludwig IA, Clifford MN and Crozier A, Anthocyanins and flavanones are more bioavailable than previously perceived: a review of recent evidence, Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol, 2017, 8, 155–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodriguez-Mateos A, Vauzour D, Krueger CG, Shanmuganayagam D, Reed J, Calani L, et al. Bioavailability, bioactivity and impact on health of dietary flavonoids and related compounds: an update, Arch. Toxicol, 2014, 88, 1803–1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cladis DP, Weaver CM and Ferruzzi MG, (Poly)phenol metabolism: a primer for practitioners, Nutr Today, 2020, 55, 234–243. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mosele JI, Macia A and Motilva MJ, Metabolic and microbial modulation of the large intestine ecosystem by non-absorbed diet phenolic compounds: a review, Molecules, 2015, 20, 17429–17468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ozdal T, Sela DA, Xiao JB, Boyacioglu D, Chen F and Capanoglu E, The reciprocal interactions between polyphenols and gut microbiota and effects on bioaccessibility, Nutrients, 2016, 8, 78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faria A, Fernandes I, Norberto S, Mateus N and Calhau C, Interplay between anthocyanins and gut microbiota, J. Agric. Food Chem, 2014, 62, 6898–6902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williamson G and Clifford MN, Role of the small intestine, colon and microbiota in determining the metabolic fate of polyphenols, Biochem. Pharmacol, 2017, 139, 24–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bailey RL, Gahche JJ, Lentino CV, Dwyer JT, Engel JS, Thomas PR, et al. Dietary supplement use in the United States, 2003-2006, J. Nutr, 2011, 141, 261–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gahche J, Bailey R, Burt V, Hughes J, Yetley E, Dwyer J, et al. NCHS Data Brief, 2011, no. 61, National Center for Health Statistics, (Hyattsville, MD: ). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tuohy KM, Conterno L, Gasperotti M and Viola R, Up-regulating the human intestinal microbiome using whole plant foods, polyphenols, and/or fiber, J. Agric. Food Chem, 2012, 60, 8776–8782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cladis DP, Debelo H, Lachcik PJ, Ferruzzi MG and Weaver CM, Increasing doses of blueberry polyphenols alters colonic metabolism and calcium absorption in ovariectomized rats, Molec. Nutr. Food Res, 2020, 64, 20200031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cladis DP, Li SY, Reddivari L, Cox A, Ferruzzi MG and Weaver CM, A 90 day oral toxicity study of blueberry polyphenols in ovariectomized sprague-dawley rats, Food Chem. Toxicol, 2020, 139, 111254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.US Department of Health and Human Services, FDA, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Guidance for Industry: Estimating the Maximum Safe Starting Dose in Initial Clinical Trials for Therapeutics in Adult Healthy Volunteers, Food and Drug Administration, Rockville, MD: 2005, p. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoggatt AF, Hoggatt J, Honerlaw M and Pelus LM, A spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down: a novel technique to improve oral gavage in mice, J. Am Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci, 2010, 49, 329–334. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kozik AJ, Nakatsu CH, Chun H and Jones-Hall YL, Age, sex, and TNF associated differences in the gut microbiota of mice and their impact on acute TNBS colitis, Exp. Mol. Pathol, 2017, 103, 311–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bolyen E, Rideout JR, Dillon MR, Bokulich N, Abnet CC, Al-Ghalith GA, et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2, Nat. Biotechnol, 2019, 37, 852–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Rosen MJ, Han AW, Johnson AJA and Holmes SP, DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data, Nat. Methods, 2016, 13, 581–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lozupone C and Knight R, UniFrac: a new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities, Appl. Environ. Microbiol, 2005, 71, 8228–8235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Furrer A, Cladis DP, Kurilich A, Manoharan R and Ferruzzi MG, Changes in phenolic content of commercial potato varieties through industrial processing and fresh preparation, Food Chem, 2017, 218, 47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang J, Ferruzzi MG, Ho L, Blount J, Janie EM, Gong B, et al. Brain-targeted proanthocyanidin metabolites for Alzheimer’s disease treatment, J. Neurosci, 2012, 32, 5144–5150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Song BJ, Sapper TN, Burtch CE, Brimmer K, Goldschmidt M and Ferruzzi MG, Photo- and thermodegradation of anthocyanins from grape and purple sweet potato in model beverage systems, J. Agric. Food Chem, 2013, 61, 1364–1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Ferrars RM, Cassidy A, Curtis P and Kay CD, Phenolic metabolites of anthocyanins following a dietary intervention study in post-menopausal women, Molec. Nutr. Food Res, 2014, 58, 490–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mandal S, Van Treuren W, White R, Eggesbø M, Knight R and Peddada S, Analysis of composition of microbiomes: a novel method for studying microbial composition, Microb. Ecol. Health Dis, 2015, 26, 27663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Segata N, Izard J, Waldron L, Gevers D, Miropolsky L, Garrett WS and Huttenhower C, Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation, Genome Biol, 2011, 12, R60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Terbraak CJF, Canonical correspondence-analysis - a new eigenvector technique for multivariate direct gradient analysis, Ecology, 1986, 67, 1167–1179. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hammer O PAST (paleontological statistics) - comprehensive teaching and research package for paleontological data analysis. Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs, 2004, 36, 151. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chandra P, Rathore AS, Kay KL, Everhart JL, Curtis P, Burton-Freeman B, et al. Contribution of berry polyphenols to the human metabolome, Molecules, 2019, 24, 4220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Del Bo C, Ciappellano S, Klimis-Zacas D, Martini D, Gardana C, Riso P and Porrini M, Anthocyanin absorption, metabolism, and distribution from a wild blueberry-enriched diet (Vaccinium angustifolium) is affected by diet duration in the Sprague-Dawley rat, J. Agric. Food Chem, 2010, 58, 2491–2497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Janle EM, Lila MA, Grannan M, Wood L, Higgins A, Yousef GG, et al. Pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution of C-14-labeled grape polyphenols in the periphery and the central nervous system following oral administration, J. Med. Food, 2010, 13, 926–933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barros HRD, Garcia-Villalba R, Tomas-Barberan FA and Genovese MI, Evaluation of the distribution and metabolism of polyphenols derived from cupuassu (Theobroma grandiflorum) in mice gastrointestinal tract by UPLC-ESI-QTOF, J. Funct. Foods, 2016, 22, 477–489. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Azorin-Ortuno M, Yanez-Gascon MJ, Vallejo F, Pallares FJ, Larrosa M, Lucas R, et al. Metabolites and tissue distribution of resveratrol in the pig, Molec. Nutr. Food Res, 2011, 55, 1154–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moco S, Martin FPJ and Rezzi S, Metabolomics view on gut microbiome modulation by polyphenol-rich foods, J. Proteome Res, 2012, 11, 4781–4790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Williamson G, Kay CD and Crozier A, The bioavailability, transport, and bioactivity of dietary flavonoids: a review from a historical perspective, Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf, 2018, 17, 1054–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Ferrars RM, Czank C, Zhang Q, Botting NP, Kroon PA, Cassidy A and Kay CD, The pharmacokinetics of anthocyanins and their metabolites in humans, Brit. J. Pharmacol, 2014, 171, 3268–3282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Czank C, Cassidy A, Zhang QZ, Morrison DJ, Preston T, Kroon PA, et al. Human metabolism and elimination of the anthocyanin, cyanidin-3-glucoside: a C-13-tracer study, Am. J. Clin. Nutr, 2013, 97, 995–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Di Rienzi S and Britton R, Adaptation of the gut microbiota to modern dietary sugars and sweeteners, Adv. Nutr, 2020, 11, 616–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parker BJ, Wearsch PA, Veloo ACM and Rodriguez-Palacios A, The genus Alistipes: gut bacteria with emerging implications to inflammation, cancer, and mental health, Front. Immunol, 2020, 11, 906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fraga CG, Croft KD, Kennedy DO and Tomas-Barberan FA, The effects of polyphenols and other bioactives on human health, Food Funct, 2019, 10, 514–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Son TG, Camandola S and Mattson MP, Hormetic dietary phytochemicals, Neuromolecular Med, 2008, 10, 236–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Calabrese V, Cornelius C, Trovato-Salinaro A, Cambria MT, Locascio MS, Di Rienzo L, et al. The hormetic role of dietary antioxidants in free radical-related diseases, Curr. Pharm. Des, 2010, 16, 877–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Calabrese EJ and Baldwin LA, Hormesis: The dose-response revolution, Anna. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol, 2003, 43, 175–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hayes DP, Nutritional hormesis, Eur. J. Clin. Nutr, 2007, 61, 147–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wan M, Co V and El-Nezami H, Dietary polyphenol impact on gut health and microbiota, Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 2020, DOI: 10.1080/10408398.2020.1744512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mosca A, Leclerc M and Hugot JP, Gut microbiota diversity and human diseases: should we reintroduce key predators in our ecosystem?, Front. Microbiol, 2016, 7, 455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hodges JK, Cao SS, Cladis DP and Weaver CM, Lactose intolerance and bone health: the challenge of ensuring adequate calcium intake, Nutrients, 2019, 11, 718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rodriguez MM, Henry C, Lachcik PJ, Ferruzzi M, McCabe G, Lila MA and Weaver CM, Dose response effects of a blueberry-enriched diet on net bone calcium retention in ovariectomized rats, FASEB J, 2017, 31, 793.27871063 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hohman EE and Weaver CM, A grape-enriched diet increases bone calcium retention and cortical bone properties in ovariectomized rats, J. Nutr, 2015, 145, 253–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pawlowski JW, Martin BR, McCabe GP, Ferruzzi MG and Weaver CM, Plum and soy aglycon extracts superior at increasing bone calcium retention in ovariectomized Sprague Dawley rats, J. Agric. Food Chem, 2014, 62, 6108–6117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yousefzadeh N, Kashfi K, Jeddi S and Ghasemi A, Ovariectomized rat model of osteoporosis: a practical guide, EXCLI J, 2020, 19, 89–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cladis DP, Swallow EA, Allen MR, Gallant KMH, Ferruzzi MG and Weaver CM, Blueberry polyphenols do not improve bone mechanical properties in ovariectomized rats, J. Bone Mineral Res, 2020, 35, 232–232. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.